Three Little Pigs For Atari

Orson Scott Card

Editor, COMPUTE! Books

Five-year-old Geoffrey sat down at the computer, and a woman introduced a wolf named Wasco. "Move him to the magic door," she said. He pushed his joystick and the wolf walked over to the door, waving his arms and moving his legs. When he reached the door, the wolf flashed different colors and disappeared.

Then the picture on the screen changed, as if it were a camera panning from left to right. Geoffrey saw a straw house, with a nervous pig inside, wiggling its ears and tail. The straw salesman walked by as the woman told how the house came to be built. Then Wasco came back.

"Little pig, little pig, let me in," said the wolf, in a voice that echoed strangely.

"Not by the hair of my chinny-chin-chin," said the squeaky-voiced pig.

Geoffrey laughed aloud. The woman told him to move Wasco to Door Number One. Geoffrey did it - pausing on the way to let the wolf have a chance to take a few bites of the pig through the window. The pig was apparently safe inside, so Geoffrey moved the wolf the rest of the way to the door.

Huffing And Puffing

The wolf started dancing around while he huffed and puffed. Sure enough, the sky flashed, the "camera" panned to the right again, and the house was now a wreck. The same thing happened with the wood house, and then the wolf failed in two tries at the brick house.

The woman told Geoffrey to move Wasco to the chimney. When Geoffrey got him there, the wolf climbed up and jumped down. But there was a pot waiting down in the fireplace, and the wolf dropped neatly inside.

"I want another story now!" said Geoffrey.

But there was no other story. So Geoffrey happily repeated "The Three Little Pigs" about six times before his parents sent him to bed with a promise that he could play it again tomorrow.

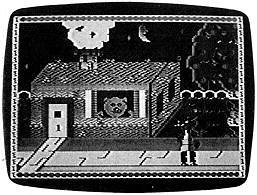

The wolf lurks outside the first pig's

house in The Magic Storybook:

Three Little Pigs.

By the fairest standard of judgment I know, that makes Magic Storybook's animated, interactive computer story a success. It is meant for children, and my very picky son Geoffrey thought it was great.

And it was, in many ways. The pictures of the houses were beautifully done, with display list interrupts allowing eight colors and many different shades on the screen at a time. The wolf and the salesman were each made up of four player/missiles combined, and despite the limitation of the 16-bit-wide format (they were tall and thin), the animation was well-done.

Artistic Screen Display

There were thoughtful extras, too. Stars twinkled. The pigs' eyes, ears, and tails were in constant motion. The artistry of the screen display was delightful. The horizontal scrolling was beautifully done - it even trembled like an earthquake when the wolf blew and blew at the brick house. The cassette loaded correctly the first time, every time, and when we wanted to repeat the story, the other side of the tape had the storytelling soundtrack only, so we didn't have to wait for a load. There was even a line-drawing replica of the cover picture, for a kid to color.

There were trade-offs, of course. That can't be helped. To create fluid, lifelike cartoon movements requires a new picture for every different body position of an onscreen character. That kind of quality takes a lot of artists a lot of time and money. That's why cheaply made cartoons have stiff, unnatural movements, faces that show no expressions, and dull backgrounds that repeat endlessly.

The same limitations apply to computer animation, only in addition to time and money, a third limitation is memory. Smooth, lifelike movement requires that every single picture be in RAM, where it can be accessed instantly. Player/missile graphics compensates a lot, because figures can be moved smoothly. But as soon as you want arms and legs to move naturally, or faces to change expressions, you run into the same old problems - every shape has to be in memory.

Limited Interaction

But that doesn't excuse all the flaws. For one thing, the interaction was very limited. All the child can ever do is move the wolf from right to left. There's a little bit of freedom: the wolf can go up and down about an inch. But if the child plays around with the wolf too long, the program takes over and moves the wolf against the child's will.

That seems like an unnecessary precaution. Why shouldn't children be free to move the wolf all around the house, if they feel like it, and take as long as they want doing it, too? It would have taken only a few dozen machine language commands to allow the wolf to go behind the house in the effort to get inside - a lot of drama would have been added to the story, and nothing is gained by making children hurry through the tale.

The sound was another problem. The background music was tolerable but unexciting. The funny voices for the wolf and the pigs were great - Geoffrey and his three-year-old sister, Emily, laughed out loud the first time through the story. But the narrator! She read in a monotone, as if she were hopelessly bored, repeating an elocution lesson, carefully pronouncing every vowel and consonant.

I couldn't help but compare Magic Storybook with PDI's interactive story Sammy the Sea Serpent. The graphics and programming in Magic Storybook are lightyears beyond Sammy. But Sammy's narrator is an excellent, excited storyteller, and the child is given meaningful tasks to perform and games to play. The six high-resolution screens and player/missile graphics in Magic Storybook cost the children the chance to really become part of the story.

The glow on my son's face when the narrator of Sammy the Sea Serpent tells him, "Sammy is home now. He couldn't have done it without you," just wasn't there at the end of "The Three Little Pigs." Some things count even more than graphics.

Magic Storybook:

The Three Little Pigs

Amulet Enterprises, Inc.

P.O. Box 25612

Garfield Heights, OH 44125

(216)475-7766

$29.95