THEY MARCHED ... LIKE MEN WHO HAD LOST ALL INTEREST IN LIFE

Project Gutenberg's Prince Rupert, the Buccaneer, by C. J. Cutcliffe Hyne This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Prince Rupert, the Buccaneer Author: C. J. Cutcliffe Hyne Illustrator: G. Grenville Manton Release Date: April 24, 2018 [EBook #57039] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PRINCE RUPERT, THE BUCCANEER *** Produced by Al Haines

THEY MARCHED ... LIKE MEN WHO HAD LOST ALL INTEREST IN LIFE

BY

C. J. CUTCLIFFE HYNE

WITH EIGHT ILLUSTRATIONS BY G. GRENVILLE MANTON

THIRD EDITION

METHUEN & CO.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

First Published . . . April 1901

Second Edition . . . June 1901

Third Edition . . . . May 1907

TO

E. C. H.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I. The Pawning of the Fleet

II. The Admission to the Brotherhood

III. The Rape of the Spanish Pearls

IV. The Ransoming of Caraccas

V. The Passage-money

VI. The Mermaid and the Act of Faith

VII. The Galley

VIII. The Regaining of the Fleet

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

They marched ... like men who had lost all interest in life . . . Frontispiece

Prince Rupert shone out like a very Paladin

Then one Watkin, a man of iron and a mighty shooter, took the lead

It would be a perpetual sunshine for me, Querida

Master Laughan endeavoured to outdo them all in desperation and valour

"Oh, I say what I think," retorted Watkin with a sour look

The secretary was occupied in leading her own.

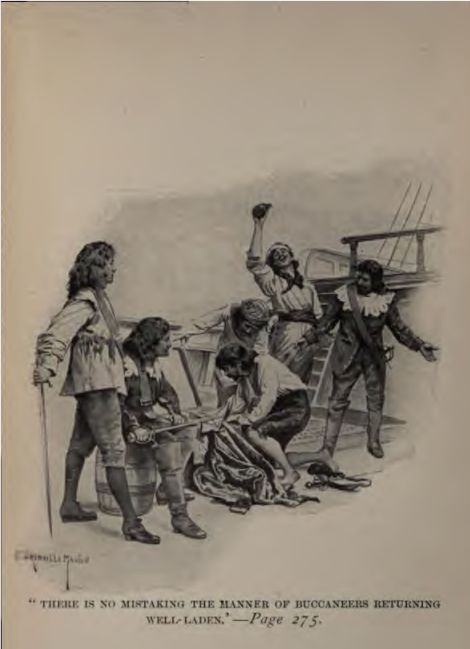

There is no mistaking the manner of buccaneers returning well-laden

"Not slaves, your Highness," said the Governor. "We call them engagés here: it's a genteeler style. The Lord General keeps us supplied."

"I'll be bound he gave them the plainer name," said Prince Rupert.

The Governor of Tortuga shrugged his shoulders. "On the bills of lading they are written as Malignants; but judging from the way he packed the last cargo, Monsieur Cromwell regards them as cattle. It is evident that he cared only to be shut of them. They were so packed that one half were dead and over the side before the ship brought up to her anchors in the harbour here. And what were left fetched but poor prices. There was a strong market too. The Spaniards had been making their raids on the hunters, and many of the engagés had been killed: our hunters wanted others; they were hungry for others; but these poor rags of seaworn, scurvy-bitten humanity which offered, were hardly worth taking away to teach the craft—Your Highness neglects the cordial."

"I am in but indifferent mood for drinking, Monsieur. It hangs in my memory that these poor rogues once fought most stoutly for me and the King. Cromwell was ever inclined to be iron-fisted with these Irish. Even when we were fighting him on level terms he hanged all that came into his hands, till he found us stringing up an equal number of his saints by way of reprisal. But now he has the kingdom all to himself, I suppose he can ride his own gait. But it is sad, Monsieur D'Ogeron, detestably sad. Irish though they were, these men fought well for the Cause."

The Governor of Tortuga emptied his goblet and looked thoughtfully at its silver rim. "But I did not say they were Irish, mon prince. Four Irish kernes there were on the ship's manifest, but the scurvy took them, and they went overside before reaching here."

"Scots then?"

"There is one outlandish fellow who might be a Scot, or a Yorkshireman, or a Russian, or something like that. But no man could speak his lingo, and none would bid for him at the sale. You may have him as a present if you care, and if perchance he can be found anywhere alive on the island. No, your Highness, this consignment is all English; drafted from foot, horse, and guns: and a rarely sought-after lot they would have been, if whole. From accounts, they must have been all tried fighting men, and many had the advantage of being under your own distinguished command.—Your Highness, I beseech you shirk not the cordial. This climate creates a pleasing thirst, which we ought to be thankful for. The jack stands at your elbow."

Prince Rupert looked out over the harbour, and the black ships, at the blue waters of the Carib sea beyond. "My poor fellows," he said, "my glorious soldiers, your loyalty has cost you dear."

"It is the fortune of war," said D'Ogeron, sipping his goblet. "A fighting man must be ready to take what befalls. Our turn may come to-morrow."

"I am ready, Monsieur, to take my chances. It is not on my conscience that I ever avoided them."

"Your Highness is a philosopher, and I take it your officers are the same. Yesterday they rode with you boot to boot in the field, ate with you on the same lawn, spoke with you in council across the same drum-head. To-day they would be happy if they could be your lackeys. But the chance is not open to them; they are lackeys to the buccaneers."

Prince Rupert started to his feet. "Officers, did you say?"

"Just officers. The great Monsieur Cromwell has but wasteful and uncommercial ways of conducting a war. He captures a gentle and gallant officer; he does not ask if the poor man desires to be put up to ransom, but just claps the irons on him, and writes him for the next shipment to these West Indies, as though he were a common pikeman." The Governor toyed with his goblet and sighed regretfully—"'Twas a sheer waste of good hard money."

"And you?"

"We kept to the Lord General's classification, and sold gentle officer, and rude common soldier on the same footing. There was no other way. We were too far off your England here to treat profitably for ransom. Besides, the estates of most were wasted during the war, and what was left lay in Monsieur Cromwell's hands."

"All the gentlemen of England are beggared. They sent their plate to the King's mint to be coined for the troops' pay; they pawned their lands; and now they are sent to be butcher-boys to horny-handed cow-killers. I think you have dealt harshly, Monsieur D'Ogeron."

"It was your war," said the Governor good-humouredly, "not mine; and the harshness of it was out of my hands. The men were sent here, and I dealt with them in the most profitable way. If it would have paid me to weed out the officers, I should have done it. As it didn't, I e'en let them stay herded in with the rest."

"But surely, Monsieur, you must have some regard for gentle blood?"

"Mighty little, mon prince, mighty little. I had it once in the old days, in France; but I lost it out here. It's not in fashion. A quick eye and a lusty arm we value in Tortuga and Hispaniola more than all the titles a king could bestow. Gentility will not fill the belly here, neither will it ward off the Spaniards, neither will it despoil them of their ill-got treasure to provide the wherewithal for an honest carouse. What we value most is a little coterie of Brethren of the Coast sailing in with a deep fat ship, with their numbers few and their appetites whetted. To those we are ready to bow, as we did once in the old countries to knights and belted earls—till, that is, they have spent their gains."

"And then?"

"Why, then, mon prince, we are apt to grow uncivil till we see their sterns again as they go off to search the seas for more. Oh, I tell you, it's a different life here from the old one at home; and a rustling blade, if he can contrive to remain alive, soon makes his way to the top, be he gentle, or be he mere whelp of a seaport drab."

"You state your policy with clearness. This is not known in France, and there, I make bold to say, Monsieur, it would not be liked."

The Governor drank deeply. "Here's to France," quoth he, "and may she always stay a long way off! I'm my own master here, and have a strong place and a lusty following."

"Stronger places have been taken," said the Prince.

"Not if they were snugly guarded," said D'Ogeron. "I use my precautions. There are two entrances to this harbour, but only one channel. There are many bays, but only one anchorage. Your ships are in it now; my batteries command them."

"Monsieur," said Rupert stiffly, "do you distrust me?"

"Except for my own rogues, and you are not one of them——"

"Thank God!"

"Except for my own rogues, I trust no one."

"Monsieur," said Rupert, "I am not in the habit of having my word doubted. I have had the honour to inform you before that I came in peace."

"So have done others, and yet I have seen them bubble out with war when it suited their purpose."

"Monsieur, you may have your own individual code of honour in these barbarous islands, but I still preserve mine. You have seen fit to put in question my honesty. I must ask you to call back your words, or stand by the consequences."

The Governor winked a vinous eye. "You don't catch me fighting a duel," said he. "The honour of the thing we may leave out of the question: we don't deal in it here. And beyond that, I have all to lose and nothing to gain."

"Monsieur," said the Prince, "you have your sword, and I have mine. I can force you either to fight or apologise."

The Governor wagged his goblet slowly. "Neither one nor the other," said he. "Alphonse," he cried, raising his voice, "haul across that curtain."

There was a scuffle of feet. A piece of drapery that seemed to hide the wall behind the Prince's chair clattered back on its rings, and showed another room, long, narrow, and dusky. In it at the farther end was a demi-bombarde, a small wide-mouthed piece on a gun carriage, with a man standing beside its breech holding a lighted match over the touch-hole.

The Prince turned sharply to look, and then slewed round to the table again. "It covers me well, but I have known a single shot to miss."

"But not a bag of musket balls, mon prince, with a small charge behind them," said the Frenchman politely.

"They would be safer," said Rupert. "Yes, Monsieur, it is a pretty trap, but to me it scarcely seems one that a gentleman would set for a guest."

D'Ogeron shrugged his shoulders. "It contents me," he said, reaching for the black-jack. "I have ceased to be a gentleman. I am Governor of Tortuga."

"If I cannot compel you just now to fight me for your discourtesy," said Rupert, "at least I will not drink with you." And he spilled his liquor on the floor.

"Every man to his humour," said D'Ogeron. "The jack's half full yet, but I'm not averse to doing double duty. This sangoree puts heart in a man. Now touching these engagés we started from: there is a way open by which you can serve them quite to their fancy. All who are left, that is, for I make no doubt that some have not survived. Newcomers are apt to be full of vexatious faults, and the cow-killers are not wont to be lenient when their convenience is injured. Give out that you are here with money, and ready to buy, and within a month I'll have all of them brought here to look at, with their prices written in plain figures. Say the word, mon prince, and I'll send out news this very day."

It irked Prince Rupert to deal with this man, it irked him to sit in the same room with such a fellow; but the woes of those that had fought by his side cried aloud for relief, so he swallowed back his nausea and spoke him civilly. Besides, if the Governor chose to pocket the affronts and go on sipping his sangoree, it was the Governor's affair. So the Prince said that he was ready to buy back the liberty of those officers who had served his late majesty King Charles in the wars, and was prepared to remain in Tortuga harbour with his three ships till these were brought in.

"Well and good," said D'Ogeron. "But I must warn your Highness that prices will rule high. When your very excellent friends were sold here, newly out of the ship, being raw with wounds, and galled with their shackles, and damaged with scurvy, they went cheap. But since then they have been in training as hunters, and porters of meat, and makers of bucan, and dressers of hide, and so they have acquired value as handicraftsmen. Moreover, when ransom is spoken of, it is always our custom to acquire new interest in a prisoner. You take me?"

"I do. Had I one tenth of your commercial power, Monsieur, the King, my master, for whom I came out here to glean the seas, could keep a richer court at the Hague."

The Governor leaned across the table and stared. "Do I hear you say you are working for Charles II.?"

"Certainly. I am his servant since his late Majesty's murder. His kingdom for the nonce is unhappily in the hands of others, and with it the natural revenues. A king must have a court; a court needs money; I sail the seas to win that money: the thing is simple."

Monsieur D'Ogeron hit the table. "The thing is unheard of," he cried. "Loyalty is a home-growth which does not bear transporting across the seas. In France, in the old days, I was the king's man—I forget what king's. I left France full of that loyalty, and for a while it lasted. But when my ship ran into the trade winds, it began to ooze from me, and when I got set down here, in these islands of the Caribbean, there was but a dim memory of that loyalty left. France is so many a weary league away, that the King's shadow cannot reach across the seas. For a while I missed it; for a while there was a blank in my life. And then I found another master: a master whom I could always admire and strive for; a master whose every action interested me, whose every woe was mine; and him I have served this many years with infinite zest and appetite. Never had man a master he wished to serve so well."

"May I hear his name?" the Prince asked.

The Governor turned to a silver mirror which hung against the wall, and lifted his goblet.

"I drink to him," he said, "with all heartiness. His name is Camille Baptiste D'Ogeron, patron of the buccaneers."

"And skimmer of their gains?"

"Skimmer of their gains, most certainly, mon prince, or why Governor of Tortuga? What am I else but a king? I have no hollow pomp about my court, it is true, but I could have it if I chose to pay. I could have drums beat in my path when I went abroad, and powder burned upon my saint's day. I could have courtiers in silken robes and golden chains, and a palace with forty rooms instead of four. But I take only what suits my whim. My visitors come in tarry breeks or the bloodied shirts of cow-hunters. My attendants can make a roast, or brew a bowl, or slit a throat with equal glibness. My enemies, when they call, leave behind them their heads on the spikes above the gateway. And I have also the delicate joys of domesticity. Though I have been widowed these nine times, I married a new wife brought in by one of the ships only the other day, and already she adores me."

Prince Rupert sighed. "I can conceive," he said, "that the situation would not be intolerable for some men. There is a certain relish in robbing the Spaniard."

"More for you, mon prince, than for me. They are Pope's men, and I was a Pope's man bred myself. You were always Protestant."

"I glory in it," said Rupert fervently, "though it has made me a ruined fellow from my birth up."

"There you are, then," said the Governor. "Take your revenge, which is here ready to your hand, and grow rich at one and the same time."

"I shall take my revenge," said the Prince quietly, "and I shall take revenge for others also. But it is my King who will have the riches."

"Yet, if it could be otherwise," said the Frenchman musingly: "if you would follow what is in the atmosphere out here, and be content to fight for your own hand, what a glorious future there would be before you! There are with you three ships in harbour now: a very tolerable commencement. You could take them up a creek to careen, and clean them from the weeds of the voyage, and re-set-up your rigging, and get all put a-tauto. You have pretty enough crews on board already. I can get you also those of your late soldiers whom Monsieur Cromwell sent me, and who will be none the worse for their short apprenticeship with the buccaneers. There are hundreds of the buccaneers themselves that would join in such an enterprise, and I also could lend a couple of well-found ships to assist it.

"And what is this enterprise?"

"Seize every plate ship that's sent home to Spain. Sack every city on the Main in its turn, squeeze out all the gold, and sail away and leave its people to spin more."

"You propose I should do this as your lieutenant?"

"That sticks in your gizzard, eh, mon prince? But, as it chanced, I was not going to make any such suggestion. I never aspire to having men of your calibre as my subjects. They would take too much looking after, and I have no wish to find one from below climbing up and trampling on me, and becoming chief in my place. This governorship has been too hard to get, and is too snug a property to jeopardise for the mere ambition of having Rupert Palatine for a mere week or so as my dutiful lieutenant." And Monsieur D'Ogeron winked pleasantly. "No, mon prince, go and seize an island for yourself, and set up a government, and we will call ourselves allies. We will form a buccaneer kingdom with a dual head, and there will be no limit to our prosperity. Look at the crop there is at hand: wine, women, meat, corn, silks, pearls and gold in all abundance. All the strong men will flock to us and help in the taking. The Spanish power will melt away like sand cliffs before a sea."

Prince Rupert thrust back his chair from the table and smote the arm with his fist. "Have done, Monsieur!" he said. "It is against my honour that I should listen to you more. I came out here as a King's man, and if life remains to me, it will be as his man that I go back."

"But," said the Governor, with a puzzled brow, "your King's Cause is distant; it is weak; it is nearly on the ground; it is doubtful if it ever pulls round again. Nay, your Highness, by this time, for aught you know, the Second Charles has followed the way of his father, and there is no Cause left."

"Then I shall build it up again and fight for it. In Europe, Monsieur, we do not esteem a man any the less honourable because he keeps his fidelity to a Cause that is for the moment drooping."

"Well," said Monsieur D'Ogeron, "I am thankful that I have left Europe behind, with those old unpracticable ideas." He leaned back in his chair and stretched. Then he laughed craftily, and went on with his speech. "As it seems, then, we cannot trade over this idea of a buccaneer kingdom, your Highness, let us go back to the question of ransoming these engagés. You are prepared to pay good hard money down?"

The Prince frowned. "For a gentleman, Monsieur, you are unpleasantly commercial."

"Your Highness rather wearies me," said the Governor, with a whimsical shrug. "Gentility I have dropped, as being quite unprofitable; and as for keenness over a bargain, why, there I could skin a Jew; so now you have a fair and final warning."

"I have no money at present."

"I did not suppose you had. Ships which sail from here to the Old World are ofttimes rich; but ships coming here, never. Since history began, they have always been barren and empty—or why else should they come?"

"I will make payments, Monsieur, out of the first prizes which come into my hands."

"I hear your Highness say it. But—Tortuga is not Europe, and we give mighty little credit here. If you were known to be fighting for your own hand, it might be different. But when you openly say you are merely an admiral of some king across the water, you speak beyond our simple minds altogether. I answer not only for myself: I answer for the whole community. You must offer some other scheme, mon prince, or your friends must stay on as engagés and work out their time. Come, think it out. I do not wish to hurry you."

Prince Rupert sat with his chin in his fingers and pondered deeply, but no schemes came to him. It irked him terribly to think that the men who had fought by his side during all the battles of the war should be left unrescued in this horrible servitude, whilst he was at hand with the will to set them free, and only lacking of the bare means. And if fighting would have done the deed, the Prince would have recked little of the odds against him. But though he captured all Tortuga, with its forts and batteries, and killed the Governor, yet he would be no more forward in his design. For those he wished to relieve were scattered in ones and twos far over the Savannahs of Hispaniola across the strait, and nothing but the good-will of Monsieur D'Ogeron could make the buccaneers, their masters, bring them in.

The Governor at the end of the table smoked tobacco and sipped his sangoree. He seemed quite contented, and perhaps a little drowsy.

Prince Rupert stood up, and began to walk to and fro across the chamber, as was his wont when thinking deeply. But scarcely had he left his chair, when the roar of an explosion shook the place, and the chamber was filled with smoke, and the chair itself and a part of the table beyond were blown to the smallest of splinters.

But at the head of the table the Governor sat unmoved, and, as it seemed, unstartled; and presently he began to laugh. "'Fore God," he said, "that was a sleepy rogue of a cannonier. Has your Highness guessed what happened?

"No," said the Prince. "Your efforts at hospitality are somewhat beyond me."

"Why, the man with the lighted match in his hand has been growing more and more drowsy, and nodding and nodding, till at last his hand drooped down over the priming. When the piece fired I chanced to look round, and saw him waken and start, as though he had been hit himself. 'Twas a most comic sight."

"Through his carelessness I have had a most narrow escape."

"But you did escape," said the Governor. "And the damage done to the chair and table I will forgive him for the amusement he afforded me."

"I must request you, Monsieur," said the Prince, "to order this man a flogging."

The Governor was all affability. "Mon prince," quoth he, "if it pleases you, he shall be flogged first and hanged afterwards. Or would you prefer that he should have his wakefulness improved by a generous taste of the rack? You have had a start. I had forgot you were newly from Europe and would care for these things. We think little enough of such small humours here, so long as we are not hurt. But you are fresh from the Old World, and my man shall pay dearly enough for his indiscretion."

The Prince frowned. "I wonder, Monsieur," he said, "that you do not punish the man as taking away your only guard over me."

This time Monsieur D'Ogeron laughed outright. "Mon prince," he said, "you have small idea of the completeness of my defences. Were it my will, I could have you safe in an unbreakable prison before another second had passed."

"I do not take you, Monsieur."

The Governor rubbed his hands appreciatively. "My dungeons," he said, "are beneath this chamber, rock-hewn, deep and vastly unpleasant. The floor on which we stand is so ingeniously contrived that at will any portion of it can be made to give way, and drop an inconvenient person into safety below. I have a trusty knave at hand attending on the bolts."

"Who is probably asleep, like your other fellow."

The Governor frowned. "I do not think so, your Highness. But we will soon see. I might call your attention to the embrasure of the window behind you. In case other foothold goes, it will afford you a scanty seat." Then, lifting his voice, he cried loudly for "Jean Paul!"

On the instant a great flap of the floor beneath the Prince's feet swung downwards, and had not Rupert been warned, there is not a doubt but that he would have been shot helplessly through the gap into the prison beneath. But as it was, with a scramble he reached the ledge of the window, and sat there cursing aloud at Tortuga and all the monkeys and the monkeyish tricks it contained.

It was plain the Governor wished to laugh—for when half drunk he was a merry enough ruffian—but he saw the Prince's rage and choked back his mirth. "Nay, your Highness," he said, "you brought it on yourself by doubting whether my man Jean Paul stayed awake. I have known all my fellows long. Alphonse drowses sometimes when the heat is great and he has liquor in him, but, Jean Paul never. That is why I have set Jean Paul over the strings which govern the bolts, and he has never failed me, and never pulled the wrong string. And it is no light business to keep the tally of them either, for there is a separate string for every square fathom of the floor."

"You keep a most delicate care of your health, Monsieur."

"It is necessary," said the Governor, with a shrug. "I have some queer callers. Men in these seas want many things, and when they cannot get them for the asking, they are not averse to using violence if they think it will succeed. I dare lay a wager, mon prince, that if you saw those late officers of yours, which Monsieur Cromwell sent me, standing by the harbour side, you would not think twice about clapping them on board and carrying them to sea without a piastre of recompense?"

"It would be my bare duty to gentlemen who have been my very faithful comrades."

"And your King's servants. How far would his present Majesty go towards ransoming these unlucky soldiers?"

"He would go far, Monsieur. I have no commission from him to speak upon the matter: I could have no commission, seeing that his Majesty knew no more than I that Cromwell has sent unfortunate cavaliers to be enslaved in these savage seas; but I take it upon myself to say that his Majesty would sacrifice much to see them relieved."

"Well," said the Governor, "if he sends out money, I will see the matter most circumspectly attended to."

"He can send out no money," said Rupert gloomily. "His Majesty has nothing save for what I earn for him."

The Governor spread his hands. "Then what can you expect? There is nothing for it but to let your good friends continue their employment, unless——"

"Unless what, Monsieur?"

The Governor dropped his insouciance and stood to his feet. The drink seemed to warm into life within him. The Prince was still sitting absurdly enough in the window embrasure, with the fallen trap yawning beneath his feet. D'Ogeron strode up and faced him across the gap. "Give me the services of your fleet for six short months," he cried, "and the men shall be yours. We will send the ships away to-morrow to careen. I will despatch messengers, and these cavaliers of yours shall join them before they are cleaned. Then they shall sail away to harry a Spanish town on the Main, and their earnings during those six months shall count for all the ransom."

"It is a bargain," Rupert said. "The King will forgive my alienating his revenues for the sake of these cavaliers who have served him so well. So, Monsieur, I sell myself into the service of the Governor of Tortuga for six desperate months."

"Stay a moment," said the Frenchman. "I made no design on your Highness's utility. It is part of my design that the fleet should sail under an officer of my own, and that your Highness should stay on here, and accept my poor hospitality."

"And for why, Monsieur? Do you honour me by doubting my capacity as an admiral?"

"By no means. I have the highest opinion of your fighting genius, mon prince. But I would like to ensure that the fleet, after glutting itself with spoil on the Spanish Main, called back in this harbour here, and did not sail direct to Helveotsluys or some other port of Holland."

"So, Monsieur, you doubt my poor honesty? You do well to put a barrier between us, for this is a killing matter."

"I have learned to doubt everybody, your Highness; but I doubt you doubly because of your loyalty to this king without a kingdom, by whom you have been sent out a-foraging. Once you and your cavaliers had the gold aboard and under hatches, it might come to your memories that this king of yours was poor, and wanted immediate nourishment, and that Monsieur de Tortuga could bear to have his account settled on a later day. You take me?"

"I cannot bargain with you," said Rupert violently. "I will not be separated from my fleet. But if hard necessity makes me desert these unfortunate cavaliers now, be assured that I do not forget them. And when opportunity arrives, and I come back to rescue them, look to yourself, Monsieur."

"You may trust me to do it," said the Frenchman. "I am always ready to receive my visitors fittingly. That is why I remain Governor of Tortuga. Well, your Highness, for the present negotiations seem at an end between us. To-morrow I suppose you will buy what food you have moneys for, and draw anchor, and be off outside towards the Main, to set about your earnings. But for the present I have a kindliness towards you, although in truth you have yielded me but very slender deference, and I would e'en let you have a passing look at these good comrades from whom you have been so cruelly parted."

"What, you have them here, then?"

"Some of them are coming to the Island now with their produce. Looking over your Highness's shoulder through the window, I saw three canoe-loads of them disappear behind the point. If it please you to take a short promenade in my company, you can watch their march when they land."

"Monsieur," said the Prince, "I accept your condescension. But first you must make me a pathway across this gap. I cannot fly."

"That can soon be done," said the Governor. He put a finger through his lips and whistled shrilly. A man stepped into the room from behind a curtain. "Jean Paul," said the Governor, "the drawbridge." The man lugged a plank from beneath the table, threw it across the space in the flooring, and assisted the Prince to cross. The Governor himself handed his walking-cane and plumed hat, and together they passed out of the chamber, Jean Paul and Alphonse following, with hands upon their pistols.

They walked leisurely through the defences of the castle, for Monsieur D'Ogeron was by no means loth to advertise his strength, and arm in arm they went out through the massive gateway, with its decoration of shrivelled heads, once worn by Monsieur D'Ogeron's enemies. They paced with gentle gait along the sun-dried path beyond, the Prince discoursing on philosophy, and engraving, and the gentler sciences, according to his wont, as though he had no thought beyond, and the Governor speaking of the fellows they passed, and the quantity of gold each in his time had wrested from the Spaniards. The Governor had but one thought to his head; but the Prince, whatever his thoughts might be, had always elegant words on other matters with which to cloak them.

The Prince used his eyes keenly as he walked, but could discover little of that lavish wealth of which the Governor spoke so glibly. The wine shops were the most considerable buildings in the place, and these were mere thatched sheds without walls. Litter and squalor and waste lay everywhere. Rich silks and other merchandise were trodden down in the kennel along with garbage and filth. There was no laden ship in just then, with a crew to be fleeced, and the women of the place hung about in disconsolate knots bewailing their draggled finery. The dwelling-houses were mere hovels of mud and leaves: the only warehouse for goods was the open beach.

The Governor must have read the Prince's glance, for he shrugged an apology. "You see us," he said, "in a state of ennui. But let one shipload of plunder come from the Main, and another of wines arrive from Bordeaux, and the place is a babel of life and carousal. Buccaneers returned from the foray are the merriest creatures imaginable. They will have none round them that are not cheerful. They set their casks of rum abroach in the path, and swear to pistol all who will not drink with them. They strut in clothes that would look fine on an emperor. They dice for black-jacks full of fair gold coin. They love the ladies with a vehemence that only seamen can command. They sing, they shout, they scream, they fight, and they scatter their plunder with a free-handedness that is more than glorious. They count it as shame if they have a piece-of-eight remaining to them after a week ashore, and then away they go to harry the seas for more. Oh, 'tis a rustling time here in Tortuga when we have a laden ship in from the harvesting; and a Governor, who must needs drink level with the best, needs a hard head to make full use of his opportunities."

The Prince listened with a courteous bow, and picked his way with niceness amongst the squalors of the path; and presently they reached the outskirts of the sheds and the hovels, and walked between walls of tropical foliage that arched with delicate tracery into a graceful roof far above their heads. Gorgeous butterflies danced before their path, and flowers administered to them of their choicest scents. They came into an open glade hung with beauty, and the Prince exclaimed that he had been led into fairyland.

"Well," said the Governor, with a laugh, "I hope your Flightless will be contented with the fairies, for here they come."

A man appeared from a path at the farther side of the glade, and after him another, and then others. They trod with heaviness, being ponderously laden; and the leader, tearing a switch from a tree, stepped on one side and beat the others lustily as they passed him.

"Dépêchez-vous!" he screamed. "Hurry, you slow-footed dogs!" And the train with infinite weariness shuffled along at a quicker gait.

They were all dressed in rude thigh-boots of raw cowhide, with loose shirts on their upper bodies stained purple with constant bloodyings. They wore shaggy beards, and shaggy uncut hair, full of sticks and refuse. Their faces and arms were puffed with insect-bites. They were unspeakably disgustful to look upon, and yet the Prince regarded them with a softening eye.

Every third or fourth man was armed with a machete which dangled against his thigh, and a long-stocked buccaneering piece which he bore in his hand; and with his spare hand he carried a switch and belaboured the others. It was only the unarmed men who bore the burdens—one a great parcel of crackling hides, another a skinful of tallow, another a package of bucaned cow-meat, another a hog bucaned whole, and so on; and these were the engagés, the slaves for three years of the acknowledged buccaneers who were with the train, and the slaves of others who remained behind in Hispaniola to continue the hunting.

They marched across the glade, like men who had lost all interest in life, each watching the heels of the one preceding; and Rupert devoured them with his eyes. Then one tall fellow stumbled over a fallen bough, and sent his burden flying, and his owner fell upon him with a very ecstasy of switching, and the Prince stepped out and bade the buccaneer desist. He did so sulkily enough, and the engagé scrambled to his feet and resumed his pack. He was a huge red-haired man, with a livid scar across his eyebrows.

"By God!" cried the Prince, "I should know that scar."

The fellow looked up. "The Prince!" he said—"Prince Rupert! Has your Highness come in for misfortune too?"

"My share. You carried the name of Coghill, if I do not disremember?"

"Coghill," said the fellow, "and rode with your Highness through many a noisy day."

"Especially at Edgehill, lad, and earned that wipe across the face by saving my poor life."

"I did not wish to recall the debt, your Highness," said the fellow, "being in this plight. It was General Fairfax that give it me. He'd a lusty arm, and could sit a horse."

The Prince wrung his hands. "I would I could serve you, lad," he said, "but I am in sorry plight myself, and the King is as bad."

"Well," said the fellow, with a sigh, "I must make shift to serve my time. I'm tough, and a common soldier looks to taking what befalls. But for officers that was delicate nurtured, it is different. This life kills them off like flies."

The Prince groaned. "I am powerless, lad," he said—"powerless."

"If your Highness could stretch a point," the fellow persisted, "it would be good for the Colonel. He will die else."

"What colonel?"

"Sir John Merivale,—who other? Has not your Highness picked him out?" The man turned round. "Oh, there he is, just coming into the open. He has seen much misfortune since Old Noll took him at Coventry, and sent him over seas."

Prince Rupert followed the trooper's glance. A gray-haired old man, the last of the train, was staggering into the clearing under a horrible burden. He had been apportioned off to carry a side of fresh beef, killed that very morning, and was bearing it, buccaneer fashion, with his head stuck through a hole in the centre. His knees bent under him with the weight, his frail hands gripped feebly at the moist edges of the joint, but his proud old back was as straight as ever it had been in the days when he sat in his saddle at the head of the King's guards; and when a fellow engagé helped him lower his dripping burden to the ground, he thanked the man with the easy courtesy of a superior.

The Prince stepped out to greet him. "Sir John," he cried, "it grieves me terribly to see you in this shocking plight."

"Ah, Prince," the old man said, "you have caught me somewhat unawares, and my present service is at times none of the most delicate. How goes the Cause? We get sadly behind the times here both in news and attire." And with that he incontinently fell down and fainted.

Prince Rupert turned to the Governor. "Monsieur D'Ogeron," he said gravely, "I surrender. For six months the fleet is yours on the conditions you offered. Whether I do right or whether I do wrong is another matter, and when the time comes I shall answer for it to the King, my master. But in the meantime I am Rupert Palatine, and I cannot live on to see officers of mine condemned to a plight like this. The opportunity is yours, and you make your gains."

"Mon prince," said the Governor delightedly, "I honour your charity. We will have a great time together here in Tortuga drinking success to the fleet whilst it is away."

Here, then, Prince Rupert was left, a guest of Monsieur D'Ogeron, the Governor of Tortuga, a man whom he found distasteful when sober and disgusting when drunk, a man with appetites only for gold-getting and carousals, frankly devoid of honour, and caring nothing for philosophy, engravings, or any of the more humane arts and sciences.

His Highness had with him his secretary, whom he knew as Stephen Laughan (but who was a maid disguised in man's attire), and his only other attendant was a negro, a creature of Monsieur D'Ogeron's. And here it seemed he was destined to endure six months, till his ships should be again out of pawn, and he was free once more to harry the Spanish seas at the head of a stout command.

If Monsieur D'Ogeron's castle of the cliff was unappetising, the squalid settlement at the head of the harbour was more so. Twice within the first three weeks, ships of the buccaneers sailed in laden with plunder from the Main, and there were some very horrid scenes of debauchery. These men knew no such thing as moderation; lavishness was their sole ideal; and he who could riot away the gains of a year in the carouse of a night was deemed to have the prettiest manners imaginable. The squalid town and its people was a mere nest of harpies, and no one knew this better than the buccaneers themselves. Monsieur D'Ogeron they openly addressed as Skin-the-Pike; the tavern-keepers they treated as though they had been Guinea blacks; but the hussies who met them with their painted smiles on the beach, and who openly flouted them the moment their pockets were drained, were a lure the rude fellows could never resist. They kissed these women, and dandled them on their knees; they lavished their wealth upon them, and sometimes beat them, and ofttimes fought for them; but never did they seem to tire of their vulgar charms.

PRINCE RUPERT SHONE OUT LIKE A VERY PALADIN

To the onlooker, the imbecility of the buccaneers in this matter was as marvellous as it was unpleasant; and it was plain to see that the machinations of the hussies (though it cannot be denied that some had beauty) were as distasteful to Prince Rupert as they were to his humble secretary and companion. They accosted them both on their walks abroad, gibing at the secretary's prim set face. But though his Highness gave them badinage for badinage, as was always his wont with women of whatever condition, they got nothing from him but pretty words gently spiced with mockery.

It was however an orgie in the Governor's castle that put a final term to their stay in Tortuga. A captured ship came in, laden deep with gold and merchandise. A week before it had been manned by seventy Spaniards, and of these twenty-three remained alive. It had been captured by a mere handful of buccaneers who had sailed after it in an open canoe, and these strutted about the decks arrayed in all manner of uncouth finery, whilst their prisoners, half-stripped, attended to the working of the vessel. They brought to an anchor, drove their prisoners into an empty hold, and clapped hatches over them; and then stepped into their boat and rowed to the muddy beach. According to their custom they had made division of the coin on board, and each man came ashore with a canvas bucket full of pieces-of-eight for his day's expenses.

They rowed to the rim of the harbour, singing, and the harpies came down on to the littered beach to meet them. From the castle above we saw them form procession, each with a couple of the hussies on his arms, and fiddlers scraping lustily in the van. There was value enough in the clothes of them to have graced a king's court; gold lace was the only braid; and very uncouthly it sat upon the men, and very vilely upon the hussies. The fiddles squeaked, a fife shrilled, and a couple of side-drums rattled bravely, and away they went with a fine preparatory uproar to the wine shops.

From his chamber in the castle Monsieur D'Ogeron heard the landing, and commenced a bustle of preparation. A feast was to be made ready, of the best, and the buccaneers and all those of the townspeople they chose to bring with them were bidden to it; and after the more solid part of the feast had been despatched, dice boxes were to be brought forward, so that the Governor, who was well skilled in play, might make his guests pay for their entertainment.

Monsieur D'Ogeron gave the orders to his negro cooks and stewards, posted armed guards in convenient niches so that his guests could be handily shot down if they resented any part of the carousal, and then, with his two armed body-servants, Alphonse and Jean Paul, betook himself to the squalid town below, where he was received with shouts, which were not entirely those of compliment.

For three hours he was swallowed up out of vision polite, and then once more reappeared on the road which led to the castle, arm in arm with the chief of the buccaneers, with a procession fifty strong bellowing choruses at their heels. They lurched up the winding pathways, stamped through the grim gateway with its decoration of shrivelled heads, came up the ladders which gave the only entrance from the courtyard, and clattered into the long low hall of the castle, where was set ready for them a feast made up of coarse profusion. On the blackened wood of the table were hogs roasted whole, and great smoking joints of fresh meat, and joints of bucaned meat, and roasted birds, with pimento and other sauces; and before each cover was a great black-jack of liquor set in a little pool of sloppings. To a European eye the feast was rather disgusting than generous; but to the buccaneers, new from the lean fare of shipboard, it was princely; and they pledged the Governor with choking draughts every time they hacked themselves a fresh platterful.

Prince Rupert, seeing no way to avoid the scene without giving offence, was seated at Monsieur D'Ogeron's right hand; and noticing a hussy about to plant herself at the Prince's right, Stephen Laughan clapped down in that place himself, to the amusement of all, and his own confusion. His Highness's secretary (being in truth a maid) had but small appetite for orgies, and had been minded to slip away privily to a quiet chamber. But the sight of that forward hussy was too much; and sooner than let the Prince be pestered by her horrid blandishments, Stephen sat at his side throughout the meal, and attempted to discourse on those genteel matters which were more fitting to a gentleman of Rupert's station.

Each buccaneer had brought with him his bucket of pieces-of-eight, which he nursed between his knees as he sat, with a loaded pistol on top as a makeweight and a menace to pilferers; and after that all had glutted themselves with meat, they swept the joints and platters to the floor, not waiting for the slaves to remove them, and called for more drink and the dice boxes, both of which were promptly set before them. And then began the silliest exhibition imaginable; for the buccaneers, with abstinence at sea, were unused to deep potations, whilst Monsieur D'Ogeron, though he had been drinking level with the best of them, was a seasoned cask which wine could never addle; and moreover, 'tis my belief the dice were cogged. The old rogue approached them craftily too, saying at first that he had but small mind for play, being in a vein of indifferent luck; whereupon they taunted him so impolitely, that at last he seemed to give way, and in a passion offered to play the whole gang of them at once.

They accepted the challenge with shouts, and Jean Paul fetched a sack of coin and dumped it against his master's chair; and so the play began, with small stakes at first, the Governor steadily losing. The guests, in the meantime, quarrelled lustily amongst themselves, and twice a pair of them must needs step away from the tables and have a bout with their hangers, and so earn a little blood-letting to cool their tempers. But for the most part they sat in their places in the sweltering, stifling heat of the chamber, and drank and shouted, and watched the rattling dice eagerly enough, and scrabbled up the coins from amongst the slop of liquor on the tables. And as they won and the Governor lost, so much the more did they shout for the stakes to be raised, till at last the Governor yielded, and hazarded fifty pieces on every throw.

Then came a change to the fortune. Monsieur D'Ogeron, it seemed, could not be beaten. He won back his own money that he had lost; he won great store of other moneys, in fat shining handfuls; and he vaunted loudly of his skill and success. "You dared me," he cried, "to raise the stakes; and I did it, and have conquered you. And now I dare you to raise 'em again." Upon which they accepted his challenge with oaths and shouts, and the play went on. A hundred pieces were staked on every throw of the dice box, and almost every time did the Governor gather in, till Stephen Laughan, who accounted it the greatest of foolishness to lose at gaming, could have wept at the silliness of the buccaneers in not leaving off the contest. But the play progressed till each man was three-parts ruined, and it did not stop till some were asleep under the tables, and the hussies and the traders from the settlement rose in a body and dragged the rest of the seamen away.

Throughout the play Prince Rupert had sat quietly at the Governor's right hand, puffing at a long pipe of tobacco, observing with his keen eyes all that happened, and answering courteously enough when spoken to. The men around him were the rudest this world contained; esteeming themselves the equals of any, and the superiors of most. But there was a natural dignity which hedged his Highness in, over which even they did not dare to trespass; and so, by way perhaps of a sly revenge, they contented themselves by gibing now and again at his easily-blushing secretary. It was not till the play had ended, and the Governor sat back with a sigh of contentment in his great carved chair of Spanish mahogany, that the Prince saw fit to make the proposal by which he regained his liberty.

"Monsieur," he said, "I have some small skill at the dice myself. Now that your other opponents have ceased to contend, will you humour me by throwing just three mains?"

The Governor turned on him with a vinous eye. "Your Highness has seen the way we play here in Tortuga? It must be for ready money jangled down on the board."

"Money, as you know, Monsieur, I have none, else had I not been here, but away with mine own ships as their admiral, earning money for the King. But I have a gaud or two left. Here is a thumb ring set with a comely Hindu diamond-stone, which already you have done me the honour to covet. I will wager you that, against a small canoe and permission for myself and Master Laughan here to use it."

"You want to leave me!" said the Governor, frowning.

"I wish to go across to Hispaniola to see for myself these buccaneers of meat at their work, and afterwards to take up such adventures as befall."

"Your Highness will find but vile entertainment amongst those savage fellows."

The Prince glanced over the littered banquet chamber. "I was sitting here ten hours ago: I am sitting here now. Let that suffice to show I am not always fastidious."

"The fellows did feed like swine, and that is a fact," said the Governor; "but if your Highness had drunk cup for cup with them, instead of keeping a dry throat, you'd have felt it less. As for Master Laughan, I do not believe he has wet his lips once since we have sat here. He snapped at the ladies and he shuddered at the men. 'Tis my belief that if Master Laughan were stripped he'd prove to be a wench."

"Monsieur," said the Prince wrathfully, "any insult thrown at Master Laughan will be answered by myself. For his manhood I can vouch. In action he has twice saved my poor life. If it please you to take your sword, I will stand up before you now in this room."

"Pah!" said the Governor. "I do not take offence at that. I will not fight."

"You will not fight, you will not game! You own but indifferent manhood!"

"Game!" cried the Governor. "I will throw you for that thumb ring if you wish to lose it."

"Be it so," said Rupert, and quickly stretching out his hand gathered up the Governor's dice and their box.

Monsieur D'Ogeron reached out his fingers angrily. "Your Highness," he said, "give back those tools. They are mine, and I am used to them, and I play with no other."

"They content me very well," said Rupert. "As a guest I claim the privilege of using them. Look!" he said, and cast them thrice before him on to the table. "They throw sixes every time. They are most tractable dice."

The Governor of Tortuga thrust back his chair, and for a minute looked like an animal about to make a spring. But he knew when he was beaten, and being a man who regarded honour as imbecility, he sought only to make the best bargain suitable to his own convenience.

"Your Highness," he said, "the dice you hold are useful to me."

"I make no doubt of it," said the Prince. "I have watched you throw them with profit during these past many hours."

"It would please me to buy them back. I will pay for them a suitable canoe and victual, such as you ask for."

"With leave for Master Laughan to voyage with me as personal attendant?"

"I will throw him in as a makeweight if your Highness will condescend to forget any small feats which it seemed to you the dice were kindly enough to perform in my favour."

The Prince surrendered the box with a courtly bow. He could be courtly even with such vulgar knaves as the Governor of Tortuga. "You may continue to use these ingenious dice as you please, Monsieur," said he. "I am not sufficiently enamoured of your good subjects here in Tortuga to wish to set up as their champion. And," he added, "I make no doubt you will be as glad to be shut of me as I am to be rid of your society. We do not fall in with one another's ways, Monsieur. We seem to have been differently brought up."

In this manner, then, Prince Rupert and his humble secretary got their quittance from Tortuga, and put across the strait to the vast island of Hispaniola, where men of the French and English races hunt the wild cattle, and the Spaniards war against them with an undying hostility. It was in a lonely bay of this island that the blacks set them ashore, and at once the discomforts of the place gave them the utmost torment. For the night, to ward off the dews and the blighting rays of the moon, the blacks built them a shelter of leaves and branches, but there was little enough of sleep to be snatched. The air drummed with insects. In the Governor's castle at Tortuga the beds were warded by a tent-like net of muslin, called in these countries a pavilion; but these they lacked, and the expedient of the buccaneers, who fill their residences with wood-smoke, they considered even worse than the insect pest itself. In the morning they rose in very sorry case. They were sour-mouthed for want of sleep, their bodies were swollen and their complexions blotched with the bites, and the negroes (doubtless by order from Monsieur D'Ogeron) had sailed off with the canoe during the night. Of food they had but a very scanty store, of weapons only their swords, and the country beyond them was savage and deadly in the extreme.

The Prince, however, was in no wise cast down. Through the thick grasses on the bay side he discerned some semblance of a track, and saying that it was as likely to lead them to the buccaneers as any other route, shouldered his share of the provisions, and stepped out along it at a lusty pace. His secretary followed him, as in duty bound, though with great weariness; and together they toiled up steep slopes of mountain under a sun that burned like molten metal. The shrubs and the grasses closed them in on either side, so that no fanning of breeze could get nigh to refresh them; and though fruits dangled often by the side of the path, they did not dare to pluck and quench their thirst, being ignorant as to which were poison. Twice they heard noises in the grass, and fearing ambuscade, drew, and stood on guard. But one of these alarms was made by a sounder of pigs which presently dashed before them across the path; and what the other was they did not discover, but it drew away finally into the distance. And once they came upon the bones of a man lying in the track, with a piece of rusted iron lodged in the skull. But no sign of those they sought discovered itself, and meanwhile the path had branched a-many times, and was growing in indistinctness. It was not till they were well-nigh exhausted that they came upon the crest of the mountain (which in truth was of no great height, though tedious to ascend by reason of the heat and the growths), and from there they saw stretched before them a savannah of enormous width, like some great field, planted here and there with tree clumps, sliced with silver rivulets, and overgrown with generous grasses. For full an hour they lay down panting to observe this, and to spy for any signs of buccaneers at their hunting; and at last, in the far distance, saw a faint blue feather of smoke begin to crawl up from amongst a small copse of timber.

On the instant his Highness was for marching on; and although his secretary brought forward many and excellent reasons for a more lengthened halt, his Highness laughed them merrily enough to scorn, and away once more they went, striding through the shoulder-high grasses, and panting under the torrent of heat. More and more obscure did the track become as they progressed, and more and more branched. Often it seemed as though it were a mere cattle path, bruised out by passing herds. And, so uncertain were they of the directions, being without compass and not always seeing the sun, that they were fain to ascend every knoll which lay in their path to justify their course.

The march, then, it may be gathered, was infinitely wearisome and tedious, and when at last they did gain the tree clump which yielded up the thin feather of smoke, the Prince was owning to a sentiment of fatigue, and his secretary was ready to drop with weariness. They were fitter for bed than for fighting, and yet fighting was nearer to them than they at all expected.

As all the world now most thoroughly knows, the Spaniards of the New World were growing alarmed at the increasing numbers of French and English adventurers who were coming out to wrest a living from the Main and the islands of the Carib Sea, and were resolved to make great effort to oust these intruders and to continue possessing the countries to themselves alone. And seeing that all sooner or later must pass their traffic through ships, the Spaniards thought to strike at the root of the evil by exterminating the cow killers of Hispaniola, who alone could supply these ships with the necessary bucaned meat. But these men, "buccaneers" as they are currently named, indignantly resented any attempt at extermination, and rather relishing war than otherwise, fought the Spaniards who were sent to hunt them with such indescribable ferocity, that for one buccaneer killed twenty Spaniards were often left dead upon the field. For which reason the Spaniards had grown wary, scoured the country in bands which had acquired the byename of Fifties, and avoided the hunters most timidly, unless they could come upon them singly or in bands of two or three.

The smoke which the Prince and his companion had seen, rose from the cooking fire of a buccaneers' camp; and, as it chanced, other eyes besides theirs had spied it also—to wit, those set under the helmets of a prowling Spanish Fifty. But this troop and their horses were masked by an undulation of the ground, which they had cleverly made use of to secure an unobserved advance, and the buccaneers went on with their cookery with little expectation of surprise. Still by custom they always kept arms handy to their fingers, and when the Prince and Master Laughan stepped out into sight from amongst the tree stems, two steady muskets covered them, and they were roundly bidden to stop and recite their business. Even after this had been said, the buccaneers received them none too civilly, and it was not till Prince Rupert had begun to charm them with his talk—as he could charm even the most uncouth of men when he chose—that they relaxed their churlishness and invited the travellers to share their meal.

There were three of these buccaneers, two only being sound men. The third, an engagé, had been sadly gored by a wounded bull, his ribs being bared some ten inches on one side, and his thigh ripped down all its length on the other. At first sight the two visitors looked upon this engagé as a dying man; but neither he nor his companions seemed to think much of the wound, and it appeared that from the active, open-air, well-fed life that these men lead, their flesh heals after a gash with almost miraculous quickness.

There was great store of meat in the camp—the spoils, in fact, of four great bulls; but the buccaneers had grown dainty in their feeding, and nothing but the udders of cows would satisfy them, and so they had shot three other poor beasts to provide them with a single meal. For sauce there was lemon and pimento squeezed together in a calabash, and for further seasoning a knob of stone salt; plaintains served them for bread; and for drink they had the choice between water and nothing. Once the buccaneers had offered hospitality, they were gracious enough with it, pointing out the tit-bits, and insisting that their guests should do well by the meal. And in truth his Highness played a rare good trencher-hand, for he was keen set with the walk, and the cookery was surprisingly delicate. But through over-fatigue his secretary lacked appetite, and these rude hunters said they held in but scurvy account one who was so small an eater.

The meal, however, was not uninterrupted. When it was half way through its course, the Prince held up his hand for silence, and then—

"Gentlemen," said he, "were we in Europe, I should say a troop of horse were reconnoitring us, possibly with a view to making an onfall."

The buccaneers cocked their ears to listen, and one of them, a tall, pock-marked man named Simpson, whispered that the Prince was right.

"And by gum, maister," said he, "tha'd better ate up t' rest o' thee jock, or happen tha'lt find theesel' de-ad wi' an empty belly. Tha' sees this buccaneering-piece of mine? Four an' a half foot long, square stocked, an' carries a ball sixteen to t' pund. She's a real Frenchy, pupped by Gelu o' Nantes, an' she's t' finest piece i' Hispaniola. I'll drop one o' th' beggars when they top yon rise, an' I'll get three more as they come up. My mate here 's good for other three wi' 'is piece, an' when they comes to hand-grips, we'll give 'em wild-cats wi' t' skinnin' knives. If thee an' thy young man do yer shares, maister, we should bring a round score o' t' beggars to grass afore we're down on t' floor wi' 'em."

"I'm thinking," said the other buccaneer, "we'd better knock Tom's brains out before we start. I'd not like an engagé o' mine to be taken by the dons alive."

Simpson considered. "There's sense i' that," said he.

"Nay, Master Simpson," urged the gored man on the ground, "say a word for me. I can pull off a gun as I lie, and at least I can hough their horses when they come near. It's sheer waste of an extra arm not to let me earn my own killing."

Simpson cut another mouthful of meat, and ate it relishingly.

"There's sense i' ye both," quoth he, "but I think Tom's right. There's fight i' Tom still, an' them dons may as well ha' t' benefit o' what Tom can do. Happen we can claw down our twenty-five if we've luck. But mark tha', Tom, there's to be no surrendering."

"I'm not anxious," said the gored man, "to make sport for those brutes while I roast to death on a greenwood gridiron."

"Gentlemen," said the Prince, "may I ask you if you regard our position as quite hopeless?"

"Quite," said Simpson. "If tha' don't believe me, maister, ax Zebedee."

"We'll be five dead men in an hour's time," said the other buccaneer. "All I want is a good pile of dead Spaniards around us; but we'll not get twenty-five."

"I'd like to bet tha' on it," said Simpson thoughtfully.

"Gentlemen," said the Prince, "I presume you are not anxious to die just now?"

"That wants no answering from quick men," said Zebedee.

"Precisely," said the Prince; "and as you appear to be desperate, and to have no plan, perhaps you will listen to mine. I grant it may fail, but I have seen it succeed before in affairs of this sort."

"Who are you?" asked Simpson.

"I am Prince Rupert Palatine. Perhaps you may have heard of me?"

"Nay, lad, nivver. But let that be. What's thee plan?"

"That instead of waiting here to be assaulted, we should attack these horse ourselves; that we should go across to the rise yonder to seek them, and should charge furiously towards them, shouting over our shoulders as though we had a body of comrades running close upon our heels."

The Yorkshireman Simpson started to his feet, buccaneering-piece in hand.

"By gum," he cried, "young feller, that's telled us t' right thing. Happen we may scrape through yet, and bring in mony a good package o' hides an' taller, an' sup mony another jack o' old Skin-the-Pikes liquor i' Tortuga. Or happen we won't. Onyway, if t' beggars runs they runs, an' if they dunnot they dunnot, an' we gets our fight all t' same. Only thing as bothers me's Tom. I'm thinking we should give Tom a kindly shot before we start."

"Nay, Master Simpson," said Tom; "if needs must I can earn my killing with the best of you. And till that time comes I can be of use. I can shout after you from the timber, and every voice helps."

"Assuredly," said the Prince. "Tom's voice will further the plan."

"It's all very well for you to talk, stranger," said Zebedee, "but it's me that's Tom's master, and has to think for his good. It's my opinion——"

"Here they come!" cried Rupert. "Now, gentlemen, for God and the King: at the gallop, charge!"

The helmets of the Spanish horse had appeared, glistering under the sun, from behind the grasses of the rise. Three shots rang out, and three Spaniards toppled backwards out of sight, and the two sound buccaneers, reloading their pieces as they ran, sprang off after Prince Rupert and his secretary, who led, waving their swords as though to bring up other companions.

"Come on, mates!" shouted the buccaneers over their shoulders: "we have them on the hip. Quick, mates, and we'll kill the whole fifty! Quick, mates, or the cowards will be gone!" And from behind them in the timber the gored man sent shouts of encouragement in various keys, an shots as fast as he could reload his piece, whereof each one found a billet.

The Spanish horse wavered in their charge, slowed to a canter, to a trot, to a walk; and then halted. And meanwhile the Prince and Stephen Laughan faced towards them unfalteringly, and the two buccaneers followed, roaring with glee, as though the whole fifty were already prisoners in their hands.

Then someone amongst the Spaniards cried that they were betrayed, and that they were on the edge of an ambush of the buccaneers; and pulling his horse out of the line, galloped away by the line he had come. Upon which all the others, saving the seven whom Tom and the two buccaneers had shot, got their horses' heads turned, clapped in spurs, and rode as though an army were pounding along at their heels.

Zebedee came and took the Prince by the hand. "I thank you," he said, "for saving our lives."

But Simpson was not so openly grateful. "There's been no fight," said he. "Ye cannot call yon a fight. By gum, I thought we was in for summat big." And he walked back to the camp moodily, like a man who has suffered disappointment.

Still, even Simpson had sense behind his recklessness, and was the first to suggest leaving their temporary camp before the Fifty rallied and came to seek them again, and advised departing forthwith to a safer headquarters. The meat and the skins were to be left behind; the two buccaneers picked up the wounded engagé arms and heels, and carried him between them; and, with Prince Rupert and Master Laughan following, off set all five at a round pace through the grasses.

The toughness of these hunters was extraordinary. For hours they had been engaged in the chase, in skinning and dressing their quarry, in transporting great loads of meat and hides, with barely an hour's rest out of the last twenty-four.

And yet here they were, carrying their arms and a wounded man as though the weight was thistledown, and walking their good five miles to the hour. A linen tunic and short drawers reaching only to mid-thigh was all their wear, and these were dyed purple with constant bloodyings. Their powder they carried in waxed calabashes, their skinning knives in a case of cayman skin, with bullet pouch attached. Their one article of luxury and gentility was a toothpick of polished spider's leg.

To the Prince, hardened as he was by a lifelong education in camps, following in the tracks of these buccaneers was a heavy exertion. To poor Stephen Laughan (that was but a delicately nurtured maid) it was a horrid torment. Her feet seemed like lead, her legs mere whisps of stockings. Her eyes swam and her body swayed, and nothing but the dreadful thought that if she fell the Prince might slacken her dress and so discover her sex, kept her from fainting each step of the way. Yet even at that terrible situation can she look back now, and say that never once did she regret the step that she took to follow across the seas and guard this gallant gentleman she so truly and reverently loved.

The details, then, of this march are omitted, as the historian made the journey in a state bordering on the insensible; and for the same reason nothing can be said of the first coming into the main camp of the buccaneers. Even Prince Rupert, as he was afterwards gallant enough to own, was almost sinking with weariness when these strange headquarters were reached.

But sleep is a great refresher, and next morning saw his Highness quite restored, and Master Laughan remembering what was due to borrowed manhood, and making shift to disown all inconvenience from fatigue.

It was a Sabbath, and a day of great council. These strange men, the buccaneers, had come in from far and wide across the great savannahs, to recount losses, and to register vengeances against their natural enemies, the Spaniards. All were by their custom equal that had served a due apprenticeship; there was no king, there were no chiefs, there were no inferiors; and if any by his natural wit or prowess held a kind of natural headship amongst the rest, he was careful not to show it. One would suppose that they would have welcomed amongst them a prince of birth and breeding, whom they could have looked up to and followed as a natural leader; but a truthful historian must confess that they did not seize upon this inestimable advantage as readily as might be supposed.

There was no order and method about the council, but it must be owned there was little enough of boisterousness. The buccaneers sat or lounged amongst the sweet-smelling grasses, some smoking tobacco, some polishing their arms. Overhead a great delicately foliaged tree, decked with scarlet blossoms, sheltered them from the sun; and to windward fires had been built that the blue wood-reek might chase away the flies. One spoke at a time, and the others listened. All had something to tell: all were fierce against the tyrannous Spaniard.

At last came Prince Rupert's turn, and what he spoke was on a different matter.

"Gentlemen," said he, "you see in me an admiral out of employ, and I come to offer you my services for a while as leader. The Spaniards harry you on land, and you wish for vengeance. Believe me, sirs, you will not hurt them deeply by cutting off a few of their ragged horsemen. A Spaniard's deepest feelings are in his pocket, and his pocket he sends back over seas for safe keeping in Spain. Find me a canoe, give me twenty stout men, and I will engage to cut a deeper wound in the Spaniard on the seas in a month than you would here ashore in a dozen years."

Zebedee from the other side of the shadow nodded. "He's a nice notion of stratagem, brethren."

"But I seed 'im let a fight slip by when it might 'a' bin 'ad for t' axin'," said Simpson.

"You're wrong there," said another buccaneer. "I was a Parliament soldier afore Gloucester, and if you'd seen him and them damned swearing cavaliers ride through six regiments of saints, you'd ha' held your tongue upon that, friend Simpson. No; he's a glutton for a fight."

"But I was going on to say, brethren," said Zebedee, "that this sea adventuring is none to my taste. I say nothing about frying for days in an open boat, eating your boots and your belt, and going half mad for want of a drop of water; I say nothing about finding a don's ship at last, and boarding her in spite of their teeth, and then putting on fine clothes and making the beggars sail her for you into Jamaica or Tortuga with colours flying and every piece being fired off in salute. But what do we get out of it? A week's carouse, and then come back here to the hunting with a shaking hand and an eye that's clogged, and starve for half a year till the work's pulled you straight again. No, brethren; for a pleasant life, give me steady hunting, and steady pegging away at the Spaniards between whiles by way of diversion. I've tried both, turn and turn about, these dozen years, and I know which is best."

"Zebedee's growing old," cried a younger man. "I'm rusting for a turn on the seas myself. This hunting's well enough, but what's a package of greasy skins against the gutting of a fat galleon's paunch? They both take the same time to get, and think of the difference after. Last time I was over in Tortuga with three months' hard earnings, I'd empty pockets in a day."

"I'm for a venture on sea," said another. And twenty more voices said the same.

"There's sense in it," said Simpson. "I'm thinkin' I could do with a turn mysen if so be we'd a captain that——"

A man came tearing into the camp, half burst with running. "There's a pink," he gasped—"a Jack Spaniard, sailing close in along the coast. She's becalmed, and the current's been settin' her in. Her people are nigh frighted to death. I could see them with my eyes, standing to their guns."

Rupert started to his feet. "Now, sirs," he said, "a fisherman's boat with twenty volunteers, and she is ours."

The younger men amongst the buccaneers were getting ready their weapons, aglow with the thoughts of action.

"There's a canoe down by t' creek," said Simpson, "but there's nobbut one, an' she's half rotten."

"Then we must be the quicker about our business, so that she does not sink under us," said Rupert lightly.

"By gum, young feller," said Simpson, "I'm beginning to like tha'. I'll come an' all."

Already the buccaneers in a body were beginning to hurry down to the creek, and runners who had got there first were baling out the canoe in readiness. She was indeed old and rotten, and moreover she was small. By no means could a score of men crowd into her, and there was competition as to which these should be. Master Laughan, whom these rude fellows thought by reason of his slimness to be of small account, would have been quickly elbowed out had he not at sword's point asserted his claim to a place. But he kept his lodgment in the after end of the canoe next the Prince, and she slipped out into the stream of the river, and so to sea.

Ten men paddled and the other six baled, and surely no adventurers have ever tempted the seas in so unworthy a vessel. The water gushed in by a thousand cracks, and nothing but the industry of the balers could keep her afloat. A single cannon-shot would have sent her to the sharks in half a trice, and Master Laughan noted these things with a dry mouth and a heart that bade fair to leap direct from its resting-place. But Prince Rupert's eye lit as he steered, and the buccaneers bawled a psalm as a fitting start to their enterprise.

So soon as ever the canoe left shore the pink started her cannonade, though for long enough the shot fell short. But when she drew in range the Prince gave an order, and six of the paddles were taken in, and the deadly marksmen with their buccaneering-pieces shot at every head which showed. Helmsman after helmsman was dropped, till at last the tiller was left deserted. Port after port they searched with their bullets, till not a gun was manned; and then, as the leaks gained, and the canoe was sinking under their feet, they took to the paddles again and forced her madly alongside.

Like tigers the Spaniards defended their decks, and like tigers the buccaneers attacked. They had stamped their rotten vessel beneath the water when they boarded, and there was no retreat. If they could not beat the crew below, they must be beaten back themselves into the sea. They were fierce men all, fighting desperately, but even in that terrible mêlée Prince Rupert shone out like a very paladin. The Spaniards were eight to one, and when they saw the smallness of the numbers against them they resisted stubbornly. Time after time the Prince led the buccaneers to the charge, always with a less number to support him, and when at last those Spaniards who were left cried "Quarter," he had but nine followers remaining to take away their arms.

Simpson strode up across the littered decks, and smote the Prince upon the shoulder. "Young feller," he cried, "I take back what I said. Tha'rt as fond of a fight as me, an' tha'st foughten this one rarely. The lads says that if tha' can find a matelot they'll elect thee captain, an' we'll go out upon the seas to see what else we can addle."

"I am honoured by your electing," said the Prince; "but, a matelot? A sailor? I do not quite understand."

"A comerade, young feller, if tha' likes it better. We buccaneers allus has a matelot with whom we divides, come good fortune, come bad."

"If it is the custom of the brotherhood I will do as you wish. Master Stephen Laughan shall be my matelot."

The Yorkshireman burst into a great roar of laughter. "Yon lad!" he said. "Why, what sort of matelot would 'e make?"

"I would have you know," said the Prince stiffly, "that Master Laughan is as good a swordsman as any on this ship."

"Oh, like enough, like enough, young feller. But what good's a sword for killing cows? It's cow killing your matelot's got to make his business, he staying ashore whilst you are away at sea. It's the custom of the brotherhood, young feller, an' tha' cannot be elected captain till tha'st thy matelot, all complete."

"Then, as Master Laughan is barred to me," said the Prince, "I know of no one more capable than yourself."

"Me!" said Simpson.

"I have seen you fight, sir, and I have formed a great estimate of your capabilities. I will do my poor best to serve you well upon the seas.

"But," said Simpson, with his pock-marked face all puckered, "t' lads has named me here as quartermaster under thee."

"Of course," said the Prince, "if you prefer their nomination to mine——"

"By gum, no," cried Simpson. "I'll go ashore. Tha'll be something to talk about. There's them as has this, an' them as has that; there's them as has pickpockets for their matelots, and very bad some o' them's turned out; but there's not another buccaneer i' all Hispaniola that has a Prince for his comerade at sea an' I'll risk t' new thing on t' chance."

"Master Simpson," said the Prince gravely, "I am indebted for your condescension. If I live, you shall have no reason to complain of your patronage."

"Well, young feller," said the buccaneer, "I hope not. But there's no denying it's a risk. I've not always heard princes very well spoken about. But onyways, off tha' goes an' addle some gold. Tha'rt a member o' t' Brotherhood o' t' Coast now, an' tha'st earned thee place wi' a very short apprenticeship. Tha'st gotten all t' seas afore thee."