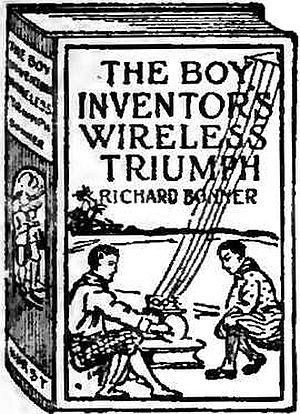

Book cover

Project Gutenberg's The Boy Aviators in Nicaragua, by Wilbur Lawton

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Boy Aviators in Nicaragua

or In League with the Insurgents

Author: Wilbur Lawton

Release Date: August 18, 2015 [EBook #49734]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE BOY AVIATORS IN NICARAGUA ***

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Rick Morris and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from scanned images of public domain

material from the Google Books project.)

Book cover

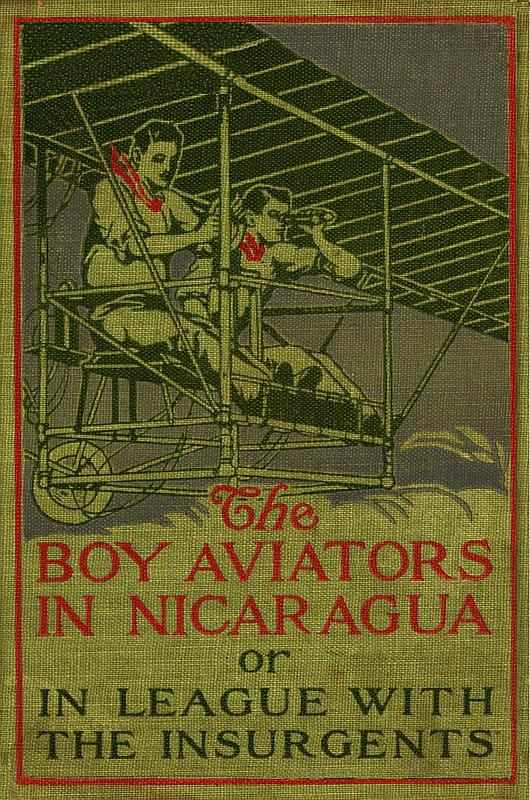

COURTESY OF SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Boys Start for the Tropics | 5 |

| II. | The Storm-Clouds Gather | 23 |

| III. | Billy Barnes of the Planet | 38 |

| IV. | The Two-Fingered Man | 50 |

| V. | Rogero is Checkmated | 61 |

| VI. | Frank to the Rescue | 70 |

| VII. | Feathering the Golden Eagle | 85 |

| VIII. | Billy Barnes Takes the Warpath | 94 |

| IX. | The Midnight Bell | 106 |

| X. | The One-Eyed Quesal | 118 |

| XI. | Billy Barnes is Trapped | 128 |

| XII. | The Aviator Boys’ Bold Dash | 139 |

| XIII. | Frank Takes a Desperate Chance | 149 |

| XIV. | Saved by an Aeroplane | 159 |

| XV. | The Boys Discover the Toltec’s “Sesame.” | 171 |

| XVI. | The Figure on the Cliff | 181 |

| XVII. | The Toltec’s Stairs | 191 |

| XVIII. | The Ravine of the White Snakes | 203 |

| XIX. | The Boys are Trapped | 213 |

| XX. | The Lone Castaway | 226 |

| XXI. | Dynamiting to Freedom | 237 |

| XXII. | In an Aeroplane in an Electric Storm | 247 |

| XXIII. | Saved by Wireless | 257 |

| XXIV. | Unloading an Army | 267 |

| XXV. | Leagued with Insurgents | 278 |

| XXVI. | The Flower of Flame | 290 |

| XXVII. | Prisoners of War | 303 |

| XXVIII. | Facing Death | 314 |

| XXIX. | Friends in Need | 324 |

It was a bitter evening in late December. Up and down the East River tugs nosed their way through the winter twilight’s gloom, shouldering aside as they snorted along big drifting cakes of ice.

At her pier, a short distance below the Brooklyn Bridge, the steamer Aztec, of the Central American Trading Company’s line had just blown a long, ear-piercing blast—the signal that in half-an-hour she would cast off her lines. In the shrill summons there was a note of impatience; as if the ship was herself as eager as her fortunate passengers to be off for the regions of sunshine and out of the misery of the New York winter.

The Aztec had been due to sail at noon that day, as the Blue Peter floating at her mainmast head had signified. Here it was, however, a good hour since the towering mass of skyscrapers on the opposite side of the river had blossomed, as if by magic, into a jewel-spangled mountain of light and her steam winches were still clanking and the ’longshore men, under the direction of the screech of the boss stevedore’s whistle, as hard at work as ever. No wonder her passengers fretted at the delay.

Not the least eager among them to see the ship’s restraining lines cast off were Frank and Harry Chester, known to the public, through the somewhat hysterical pæans of the Daily Press and the rather more dignified, but not less enthusiastic articles of the technical and scientific reviews, as the Boy Aviators. It was an hour since they had bade their mother and an enthusiastic delegation of boy and girl friends good-bye.

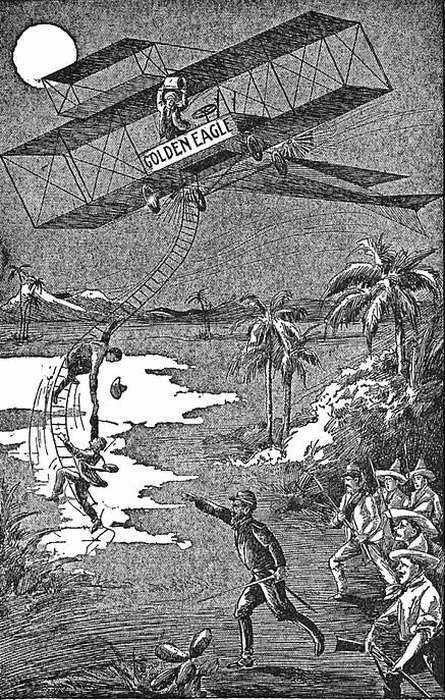

Side by side the youths paced the deck muffled in huge overcoats and surveying anxiously, as from time to time they approached the forward end of the promenade deck, a lofty pile of boxes that contained the various sections of their aeroplane the Golden Eagle which had made the sensation of the year in aviation circles.

Ever since the Golden Eagle, a biplane of novel construction, had carried off from all competitors the $10,000 prize for a sustained flight offered by J. Henry Gage, the millionaire aeronaut at the White Plains Aerodrome, the boys had become as well-known figures in New York life as any of the air prize contestants during the Hudson-Fulton Exhibition. Frank, the eldest, was sixteen. A well-grown, clean-lived-looking boy with clear blue eyes and a fearless expression. His brother, a year younger, was as wholesome appearing and almost as tall, but he had a more rollicking cast in his face than his graver brother Frank, whose equal he was, however, in skill, coolness and daring in the trying environment of the treacherous currents of the upper air.

With the exception of a brief interval for lunch the two boys had amused themselves since noon by watching the, to them novel, scene of frantic activity on the wharf. The ships of the Central American Trading Co. had a reputation for getting away on time and the delay had grated on everybody’s nerves from the Aztec’s captain’s to the old wharfinger’s; in the case of the latter indeed, he had attempted to chastise, a short time before, an adventurous newsboy who had ventured on the pier to sell his afternoon papers. Frank had intervened for the ragged little scarecrow and the boys had purchased several copies of his wares. They had a startling interest for the boys which they had not suspected. In huge type it was announced in all, that the long threatened revolution in Nicaragua had at last broken out with a vengeance, and seemed likely to run like wildfire from one end of the turbulent republic to the other. Troops were in the field on both sides—so the despatch said—and the insurgents were loudly boasting of their determination to march on and capture Managua, the capital, and overthrow the government of President Zelaya. Practically every town in the country had been well posted with the manifesto of the reactionaries, and had taken the move as being one in the right direction.

In the news that the revolution, the storm clouds of which had long been ominously rumbling had actually broken out, the boys had an intense and vital interest. Their father’s banana plantation, one of the largest and best known in Central America, lay inland about twenty miles from Greytown, a seacoast town, on the San Juan River. The boys were on their way there after a long and trying season of flights and adulation to rest up and continue, in the quiet they had hoped to find there, a series of experiments in aviation which had already made them among the most famous graduates the Agassiz High School on Washington Heights had turned out in its years of existence. Already in their flights at White Plains, and later during the Hudson-Fulton celebration, the boys had earned, and earned well, laurels that many an older experimenter in aviation might have worn with content, but they were intent on yet further distinction. Already they had given several trials to a wireless telegraph appliance for attachment to aeroplanes and the Golden Eagle in some private flights had had this apparatus in use. The results had been encouraging in the extreme. With the use of a greater lifting surface the boys felt that they would be justified in adding to the weight the aeroplane could lift and that this weight would be in form of additional power batteries for the wireless outfit both had agreed. In the boxes piled on the foredeck they had indeed a supply of balloon silk, canvas, wire, spruce stretchers and aluminum frames which they intended to put into use as soon as they should reach Nicaragua in the furtherance of their experiments. The conquest of the air both in aviation and communication was the lofty goal the boys had set themselves.

“The revolution has really started at last, old boy—hurray!” shouted Harry, throwing his arm in boyish enthusiasm about his staid brother Frank, as both boys eagerly assimilated the news.

“I say, Frank,” he continued eagerly, “it’s always been our contention that an aeroplane capable of invariable command by its operator would be of immense value in warfare. What a chance to prove it! Three cheers for the Golden Eagle.” In his excitement Harry pulled his soft cap from his head and waved it enthusiastically.

Frank, however, seemed to view the situation more gravely than his light-hearted brother. As has been said, Frank, while but little older in point of years possessed a temperament diametrically opposed to the mercurial nature of his younger brother. He weighed things, and indeed in the construction of the Golden Eagle, while Harry had suggested all the brilliant imaginative points, it had been the solid practical Frank who had really figured out the abstruse details of the wonder-ship’s structure.

Despite this difference of temperament—in fact Harry often said, “If Frank wasn’t so clever and I wasn’t so optimistic we’d never have got anywhere,”—in spite of this contrast between the two there was a deep undercurrent of brotherly love and both possessed to the highest degree the manly courage and grit which had tided them over many a discouraging moment. Nor in the full tide of their success, when people turned on the street to point them out, were either of the boys at all above recognizing their old playfellows and schoolmates as has been known to be the case, it is said, with other successful boys—and men.

“I don’t know, Harry,” replied Frank at length to his brother’s enthusiastic reception of the news of the rebellion, “there are two sides to every question.”

“Yes, but Frank, think,” protested Harry, “we shall have a chance to see a real skirmish if only they keep at it long enough. Confound it though,” he added with an expression of keen regret, “the paper says it’s another ‘comic opera revolution.’”

“I wouldn’t be too sure of that, Harry,” replied Frank, seriously. “When father was north last he told us, if you recollect, that a Central American revolution was not by any means a picnic. In the battle in which the United States of Colombia drove the Venezuelans from their territory, for instance, there were ten thousand dead left on the field.”

Frank halted under one of the wire-screened lights screwed into the bulkhead beside which they had been pacing to let the light of the incandescent stream brighter upon his paper. He scanned the page with rapid eye and suddenly looked up with an exclamation that made Harry cry:

“What’s the trouble, Frank?”

“Well, it looks as if on the day we are sailing for Nicaragua that that country is monopolizing the news to the exclusion of the important fact that ‘The Boy Aviators’”—he broke off with a laugh.

“Hear! hear,” exclaimed Harry, striking a pose.

“—I say,” continued Frank, “that it seems as we haven’t a look in any more. The country for which we are bound has the floor. Listen—”

Holding the paper high beneath the light, Frank read the following item which under a great wood-type scare-head occupied most of the front page space not given over to the announcement of the revolution.

“Almost as big a head as they gave us when we won the prize,” laughed Harry. “Newspaper head I mean.”

“I wish you’d be serious, Harry,” said Frank, though he couldn’t help smiling at his brother’s high flow of spirits. “This is really very interesting. Listen:”

“The body of a man about forty-five or possibly fifty years old was discovered this afternoon in an upper floor bedroom of the M—— Hotel on West Fourteenth Street. A brief scrutiny established that the man, who had registered at the hotel a few hours before as Dr. Ramon Moneague of Rivas, Nicaragua, had been strangled to death with exceptional brutality. He had been dead only about an hour when the body was discovered by a chambermaid who found the door unlocked.

“Whatever may have been the object of the murder it was not robbery, as, although the dead man’s trunk and suit-case had been ransacked and money lay scattered about the room, his watch and valuable diamond pin and rings had not been disturbed.

“Whoever strangled Dr. Moneague to death he was no weakling. Both Coroners, Physician Schenck and the detectives who swarmed on the scene are agreed upon this. The marks of the murderer’s fingers are clearly impressed upon both sides of the dead man’s throat.

“Perhaps the most remarkable feature of the case, and one which may lead to the slayer’s speedy detection, is the fact that his right hand had only two fingers. The police and the coroner’s physician and the coroner himself came to this conclusion after a brief examination of the marks on the throat. On the left side of the larynx where the murderer’s right hand must have pressed the breath out of the Nicaraguan there is a hiatus between the mark made by the thumb and first finger of the right hand, indicating clearly to the minds of the authorities that the man who killed Dr. Moneague is minus the middle and index fingers of his right hand.

“Every available detective at headquarters and from the different precincts have been put upon the case and every employee of the hotel connected with it even in the remotest way examined closely. No result has developed to date however. The clerk of the hotel admits that he was chatting with a friend most of the morning and after he had assigned Dr. Moneague to a room, and it might have been possible for a stranger to slip in and up the stairs without his noticing it.”

“There,” concluded Frank, throwing the paper into a scupper, “how’s that for a ringtailed roarer of a sensation?”

“It seems queer——” began Harry, but the sudden deafening roar of the Aztec’s whistle cut him short. His words were drowned in the racket. It was her farewell blast this time. As the sound died away, echoing in a ringing note on the skyscrapers opposite, the boys felt a sudden trembling beneath their feet.

Far down in the engine-room the force was tuning her up for her long run which would begin in a few minutes now. Already a couple of tugs that had been hanging alongside since noon had wakened up and now made fast lines thrown from the Aztec’s lofty counter to their towing bitts. It was their job to pull her stern first out into the stream where the current of the ebb-tide would swing her head to the south.

“All clear there for’ard?” it was the bearded muffled-up skipper bellowing through a megaphone from the bridge, where the equally swaddled pilot stood beside him.

“We’re off at last, Frank old boy,” said Harry jubilantly as what seemed a silence compared to the racket of hoisting in the last of the cargo fell over the wharf.

Anything Frank might have had to reply was cut short by a hoarse echo of the skippers hail, it came from the bow.

“All go—o—ne for’ard, sir.”

The officer in charge of casting off the bow lines waved his hand and a quartermaster at the stern wigwagged to the tugs to go as far as they liked.

“All go—o—ne aft,” suddenly came another roar from that quarter as the tug’s screws began to churn up the water. The hawsers tightened and the Aztec began to glide slowly backward into the stream.

At that moment from far down the wharf, there came a loud hail.

“Stop the ship—twenty dollars if I make the ship.”

A loud yell of derision was the reply from several steerage passengers clustered in the bow of the Aztec.

“Hold on, there,” suddenly roared the same vigilant old wharfinger who had earlier in the day shown such a respect for discipline that he had shooed the newsboy off the wharf, “hold on there.”

The boys heard coming up the wharf the staccato rattle of a taxicab running at top speed.

The two sailors in charge of the gangplank were at that moment casting it loose and lowering it to the wharf. They hesitated as they heard the frantic cries of the old wharfinger.

“Let go, there. Do you want to carry something away,” yelled the second officer, as he saw the gangplank under the impetus of the ship being crushed against the stanchions of the wharf.

The taxicab dashed up abreast of the landward end of the imperilled gangway. Out of it shot a man whom the boys, in the blue-white glare of the arc-lights on the pier, noticed wore a short, black beard cropped Van Dyke fashion, and whose form was enveloped in a heavy fur overcoat with a deep astrachan collar.

“Five dollars a piece to you fellows if I make the ship,” he shouted to the men holding the gangplank in place. Already the wood was beginning to crumple as the moving ship jammed it against the edge of the stanchion.

The stranger made a wild leap as he spoke, was up the runway in two bounds, it seemed, and clutched the lower rail of the main deck bulwarks just as the two men holding the crackling gangway up, dropped it in fear of the wrath of their superior officer. The man in the fur coat dived down in his pocket and fished out a yellow-backed ten-dollar bill.

“Divide it,” he said in a slightly foreign accent. Suddenly he whirled round on his heel. The old wharfinger was bellowing from the wharf that the man in the fur coat would have to wireless his address and his baggage would be forwarded. There were several pieces of it on the taxi. A steamer trunk, two suit-cases and a big Saratoga. These, however, seemed to give the new addition to the Aztec ship’s company no concern.

“My bag. My black bag,” he fairly shrieked, running forward along the deck to a spot opposite where the wharfinger and the taxi-cabby stood.

“My black bag. Throw me my black bag,” he repeated.

With trembling fingers he managed to get out a bill from his wallet. He wrapped it round a magazine he carried with a rubber-band which had confined his bill roll.

“This is yours,” he shouted, holding the bill-wrapped magazine high, so that the taxi-cabby could see it. “Throw me the black bag.”

The taxi-cabby, like most of his kind, was not averse to making a tip.

He dived swiftly into his cab and emerged with a small black grip, not much bigger than a lady’s satchel, bound at the corners with silver. It was a time for quick action. By this time the sharp cutwater of the Aztec’s bow was at the end of the wharf. In another moment she cleared it. The tide caught her and majestically she swung round into midstream, while the tugs lugged her stern inshore.

The chauffeur poised himself on the stringpiece at the extreme outer end of the wharf.

“Chuck me the money first,” he shouted at the gesticulating figure on the Aztec, “I might miss your blooming boat.”

The magazine whizzed through the air and landed almost at his feet, carrying with it the bill. The taxi-cabby, satisfied that all was ship-shape, bent his back for a second like a baseball pitcher.

“I used to twirl ’em,” he said to the wharfinger, as with a supreme effort, he impelled the black bag from his hand. There was a good thirty feet of water between the end of the wharf and the Aztec by this time, but the taxi-cabby’s old time training availed him. It was a square throw. The stranger with a strange guttural cry of relief caught his precious black bag and tucked it hurriedly into the voluminous inner pocket of his fur coat.

“He must have diamonds in it at least,” exclaimed Harry, with a laugh. Both boys, with the rest of the passengers, had been watching the scene with interest, as well they might. As for the man in the fur coat his interested scrutiny was directed with an almost fierce intensity to the pile of blue oblong cases on the fore deck, all neatly labeled in big white letters:

The man in the fur coat seemed fascinated by the boxes and the lettering on them. From his expression, as a great bunch light placed on the foredeck for the convenience of the men readjusting the hastily laden cargo, fell upon him, one would have said he was startled. Had anyone been near enough or interested enough they might also have seen his lips move.

“Well, he wants to know our bag of tricks again when he sees them,” remarked Harry, as the boys with a keen appetite, and no dread of sea sickness to come, turned to obey the dinner-gong.

With frequent hoarse blasts of her strong-lunged siren the belated Aztec passed down the bay through the narrows and into the Ambrose Channel. A short time after the cabin passengers had concluded their dinner the pilot took his leave. From his dancing cockleshell of a dory alongside he hoarsely shouted up to the bridge far above him:

“Good-bye, good luck.”

Then he was rowed off into the darkness to toss about till the steam pilot-boat New York should happen along and pick him up with her searchlight.

“Good-bye, old New York!” cried both boys, seized with a common instinct and a most unmanly catch at their throats at the same instant. From the chart house above them eight bells rang out. Already the Aztec was beginning to lift with the long Atlantic swell. The Boy Aviators’ voyage toward the unknown had begun.

Señor Don Alfredo Chester, as the boy aviators’ father was known in Nicaragua, sat in a grass chair on the cool patio of his dazzlingly whitewashed hacienda on his plantation of La Merced. He thoughtfully smoked a long black cigar of native tobacco as he reclined. The lazy smoke from his weed curled languidly up toward the sparkling sapphire sky of the Nicaraguan dry season, which had just begun; but the thoughts of Planter Chester did not follow the writhing column.

Nor had he in fact any eye for the scene that stretched for miles about him, although it was one of perfect tropic beauty and luxuriance. Refreshed by the long rainy season which here endures from April to December everything glittered with a fresh, crisp green that contrasted delightfully with the occasional jeweled radiance of some gorgeously-plumaged bird flashing across a shaft of sunlight like a radiant streak of lightning. These brilliant apparitions vanished in the darker shades of the luxuriant growth like very spirits of the jungle.

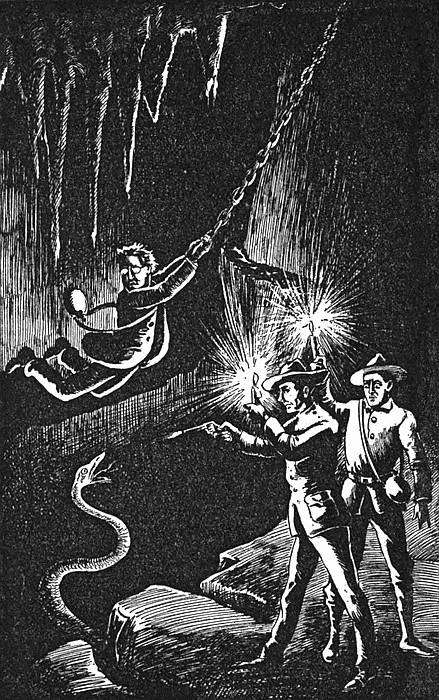

The dense tangle of rank greenery that surrounded the plantation, like a conservatory run wild, held, however, far more dangerous inhabitants than these gaudy birds. In its depths lurked the cruel but beautiful ocelots—prettiest and most treacherous of the cat family. Jaguars of huge size,—and magnificently spotted,—hung in its tree limbs, on the lookout for monkeys, fat wild hogs, or an occasional philosophic tapir. And here too in the huge trees, whose branches afforded homes for a host of multi-colored orchids lurked the deadly coral snake with its vivid checkerings of red and black and the red and yellow blood snake, the bite of either of which is as instantaneously fatal as a bullet through the heart.

From where the hacienda stood—high on the side of a steep hill on whose flanks waved everywhere the graceful broad fronds of the banana—could be obtained a distant glimpse of the Caribbean, flashing a deep sapphire as it hurled its huge swells thundering shoreward. It was on this occasional gleaming glimpse far down the San Juan valley that Señor Chester’s gaze was fixed as he thoughtfully enjoyed his cigar.

It was easy to see from even a casual glance at Mr. Chester’s strong face that his boys had inherited from him in undiminished measure the keen intellectuality that showed there, as well as the vigorous nervous frame and general impression of mental and physical power that the man gave out. It was on these boys of his that his mind was fixed at that moment. They were then by his calculations about a day away from Greytown, although as the Aztec made usually a good many ports of call on her way down the coast it was only a rough guess at her whereabouts.

As he sat on his patio that afternoon Mr. Chester would have given all he possessed to have had it in his power at that minute to have been able to keep his boys in New York, but it was too late for that now.

When it was arranged that they were going to visit him to display to his proud eyes the Golden Eagle that had made them famous, neither he, nor any other of the American planters, dreamed that the revolution was so near. So much talk had preceded it that it seemed hard to realize that it was really on and that life and property were in real danger. Some of the editors who write so blithely of comic opera revolutions, should visit Central America during one of them. They would sustain a change of heart.

In common with his brother planters he was heartily in sympathy with the reactionaries, although of course he could not honorably take an active part in the revolution as the United States and Nicaragua were nominally at peace. At Washington, however, the trend of affairs was even then being watched more closely than they guessed.

If the revolution succeeded it meant fair treatment and equitable taxes for the American planters and business men of the republic, if it failed—well, as he had expressed it a few days before at a sort of informal meeting of half-a-dozen influential planters—“We might as well shut up shop.”

Another piece of disquieting news which had come to him by cable from New York, and which had set the reactionaries and their secret friends in a frenzy, was the announcement of the murder of Dr. Moneague. As his mind reverted to this subject there was a sound of wheels on the steep drive leading up the hill to the house, and an old-fashioned chariot hung on C. springs, driven by an aged negro, in livery as old as himself, it seemed, drove up with a great flourish.

Señor Chester sprang to his feet hat in hand as it came to a halt, for beside the dignified looking old Spaniard, who occupied one side of its luxuriously-cushioned seat, there sat a young woman of the most dazzling type of the famous Castilian beauty.

“Can usta usted, Señor Chester,” exclaimed the old man, with a courteous bow full of old-fashioned grace, as the proprietor of La Merced ranch, hat in hand after the Spanish custom, approached the carriage. “We are going down to Restigue and dropped in here by the way to see if you are still alive, it is so long since you have favored us with a visit. Not since this glorious strike for liberty was made, in fact.”

“When do you expect those wonderful boys of yours?” he went on, “whose doings, you see, even we have heard of in this out-of-the-way corner of the earth.”

“Indeed, Señor Chester,” said the young woman at the yellow old Don’s side, “you must bring them to see us the very minute they arrive. My husband—Don Ramon—” she sighed.

“Brave Don Ramon,” supplemented her father, “a man in the field fighting at the head of his troops for his country is to be envied. The name of General Pachecho was not unknown when I was younger, but now—” he broke off with a quizzical smile full of the pathos of the involuntary inactivity of age.

“When Don Ramon returns triumphant from the field he can do better than merely discuss his favorite subject of aviation with my boys,” proudly remarked Señor Chester, “he can see the Golden Eagle itself. Let us hope that he will introduce it into the new army of the hoped for republic of Estrada.”

“Viva Estrada!” cried the girl, and her aged father; caught with common enthusiasm at the name of Zelaya’s foe.

“I only wish, though,” said Señor Chester, with a half sigh, “that the country was more settled. For us it is all right. But, you see, their mother——”

“Ah, the heart of a woman, it bleeds for her sons, is it not so?” cried Señora Ruiz, in her emotional Spanish manner.

“But, Señor Chester, never fear,” she continued. “My husband will not let the troops of Zelaya drive Estrada’s forces as far to the east as this.”

“But this is the hot-bed of the revolutionary movement. Zelaya has declared he will lay it waste,” objected the planter.

“While Don Ramon Ruiz leads the reactionary troops,” proudly retorted the woman with feverish enthusiasm, “Zelaya will never reach Restigue or La Merced or the Rancho del Pachecho.”

“Where the torch is laid, who can tell how far the fire will run?” remarked the Don, with true Spanish love of a proverb.

“Oh, don’t let’s think of such things!” suddenly exclaimed Señora Ruiz, “we revolutionists will be in Managua in a month. Oh, that Zelaya—bah. He is a terrible man. I met him at a ball at Managua a year ago. When he took my hand I shivered as if I had touched a toad or a centipede. He looked at me in a way that made me tremble.”

Both his visitors declined Señor Chester’s courteous invitation to enter the dark sala and partake of a cup of the native chocolate as prepared by his mocho, or man servant.

“It grows late, Señor,” said the old Spaniard, “like my life the sun is declining. Oh, that I should have lived to have heard of the death of brave Moneague! You know of it?”

A nod from Chester assured him. He went on:

“When he went to New York alone to collect revolutionary funds, I told them it was foolish, but I was old, and there were many who would not listen. Peste! how foolhardy to give him the parchment with the mystic plans on it. The secret of the lost mines of King Quetzalcoatl are worth more than one man’s life and have indeed cost many.”

“Do you mean that Dr. Moneague had the plans of the mines with him when he was killed?” quickly asked Señor Chester. “I always thought the mines were a native fable.”

“The young think many things that are not so,” was the old Don’s reply. “No, my son, Dr. Moneague did not have the plans of the mines themselves but he had what was as good, he had the bit of parchment on which—in the lost symbols of the Toltecs—the secret of the long lost paths by which the precious metals were brought to the coast was inscribed. He spent his life at this work of deciphering the hieroglyphics of that mysterious race, and he solved them; but, brave man, he was willing to yield up the secret of his life work if for it he could get money enough to save his country. You knew that his visit to New York was to see if he could not induce one of your American millionaires to give us funds?”

“I guessed it,” was the brief reply. “But why, if he knew the secret of the mines, did he not go there himself?”

“He went there once; but you who have lived long in this country know that, under Zelaya’s cruel rule he would have been worse than foolhardy to have brought out any of the miraculous wealth stored there. If Zelaya had heard of it he would have wrung the secret from him by torturing his children before his eyes.”

Shaking with excitement the old patriot gave a querulous order to the aged coachman to drive on, and waved his thin yellow hand in farewell. Señor Chester stood long watching the dust of his visitor’s carriage as it rose from the banana-fringed road that zig-zagged down the mountain side. At last he turned away and entering the house emerged a few minutes later with a light poncho thrown over his shoulders.

The chill of the breeze that sets seaward in the tropics at twilight had already sprung up and in the jungle the myriad screaming, booming, chirping voices of the jungle night had begun to awaken.

Chester made his way slowly to a small, whitewashed structure a short distance removed from the main hacienda. As he swung open the door and struck a light a strange scene presented itself—doubly strange when considered as an adjunct of a banana planter’s residence. On shelves and racks extending round the room were test tubes and retorts full and empty. The floor was a litter of scribbled calculations, carboys of acid, broken bottles, straw and in one corner stood an annealing forge. Here Señor Chester amused himself. He had formerly been a mining engineer and was as fond of scientific experimentation as were his sons.

Stepping to a rack he took from it a tube filled with an opaque liquid. He stepped to the doorway to hold it up to the fading light in order to ascertain what changes had taken place in its contents since the morning.

He almost dropped it, iron-nerved man as he was, as a piercing shriek from the barracks inhabited by the plantation workers rent the evening hush of the plantation.

The noise grew louder and louder. It seemed that a hundred voices took up the cry. It grew nearer and as it did so resolved itself into its component parts of women’s shrill cries and the deep gruff exclamations of men much worked up.

Suddenly a man burst out of the dense banana growth that grew almost up to Señor Chester’s laboratory. He was a wild and terrifying figure. His broad brimmed straw hat was bloodied and through the crown a bullet had torn its way. A black ribbon, on which was roughly chalked “Viva Estrada!” hung in a grotesque loop at the side of his face.

His clothes, a queer attempt at regimentals consisting of white duck trousers and an old band-master’s coat, hung in ribbons revealing his limbs, scratched and torn by his flight through the jungle. He had no rifle, but carried an old machete with which he had hacked his way home through the dense bush paths.

The master of La Merced recognized him at once as Juan Batista, a ne’er-do-weel stable hand, who had deserted his wife and three children two weeks before for the patriotic purpose of joining Estrada’s army, and incidentally enriching himself by loot. He had attached himself to General Ruiz’s division.

“Well, Juan! Speak up! What is it?” demanded his master sharply. Juan groveled in the dust. He mumbled in Spanish and a queer jargon of his own; thought by him to be correct English.

“Get back there!” shouted Señor Chester to the crowd of wailing women and scared natives from the quarters that pressed around. They fell back obediently.

“What is all this, Blakely?” asked Chester impatiently, as Jimmie Blakely, the young English overseer, strolled up as unruffled as if he had been playing tennis.

“Scat!” said Jimmie waving his arm at the crowd and then, adjusting his eyeglass, he remarked:

“It seems that Estrada’s chaps have had a jolly good licking.”

“What!” exclaimed the planter, “this is serious. Speak up, Juan, at once. Where is General Ruiz?”

It was with a sinking heart that Chester heard the answer as the thought what the news would mean to the radiant beauty he had been talking with but a short time before, flashed across his mind.

“Muerto! muerto!” wailed the prostrate Juan, “dead! dead!”

At this, although they didn’t understand it, the women set up a great howl of terror.

“Oh Zelaya is coming! He will kill us and eat our babies! Oh master save us—don’t let Zelaya’s men eat our babies.”

The men blubbered and cried as much as the women, but from a different and more selfish reason.

“Oh, they will kill us too and spoil all our land. The land we have grown with so much care,” they bemoaned in piercing tones, “moreover, we shall be forced to join the army and be killed in battle.”

“Blakely, for heaven’s sake take that bit of glass out of your eye, and get this howling mob out of here!” besought Chester desperately. “If you don’t I’ll kill some of them myself. Here you, get up,” he exclaimed bestowing a most unmerciful kick on the still prostrate Juan. “Oh, for a few Americans—or Englishmen,” he added, out of deference to Blakely.

“Couldn’t do a thing with them without the eyeglass, Mr. Chester,” drawled the imperturbable Blakely, “they think it’s witchcraft. Don’t twig how the dickens I keep it in.”

“All right, all right, meet me here at the house and we must hold a council of war, as soon as you’ve got them herded safe in the barracks,” impatiently said Chester, turning on his heel.

“Now come on, you gibbering idiots,” shouted the consolatory Briton at his band of weeping men and women, “come on now—get out of here, or I’ll eat your blooming babies myself—my word I will,” and the amiable Jimmie put on such a terrifying expression that his charges fled before him too terrified to make any more noise.

Out of sight of the governor, however, the Hon. Jimmie’s careless manner dropped.

“Well, this is a jolly go and no mistake;” he muttered, giving the groveling Juan a kick, where it would do the most good, “well, Jimmie—my boy—you’ve always been looking for a bit of row and it looks as if you’d jolly well put your foot in it this time—eh, what?”

While all this transpired on the ranchero El Merced, the Aztec with our heroes on board surprised everybody in Greytown, and no one more than her captain, by arriving there ahead of time. Just about the time that the Hon. Jimmie was herding his weeping charges to the barracks, her mud-hook rattled down and she swung at anchor off the first really tropical town on which the Boy Aviators’ eyes had ever rested.

Before sun up the next day there was a busy scene of bustling activity at the plantation of La Merced. The bustle extended from the hacienda to the barracks,—the news of the arrival of the Aztec having been brought to the estancia the night before by a native runner.

Old Matula, Señor Chester’s personal mocho had been down at the stables since the time that the stars began to fade urging the men, whose duty it was to look after the horses, to greater activity in saddling up the mounts, which his master, Jimmie Blakely, and their cortege needed in their ride to the coast to meet the boys.

The native plantation hands, as volatile as most of their race had forgotten the events of the preceding night in their child-like excitement at the idea of the arrival of The Big Man Bird, as they called the Golden Eagle; this being their conception of the craft gained after numerous consultations of Señor Chester.

Even Juan was strutting around the quarters and posing as a wounded hero, to the great admiration of his wife and the other women who entirely forgot that the night before he had appeared anything but a man of arms, and that his wife had subsisted mainly on the Señor Chester’s charity, since his desertion of her to become a patriot.

Jimmie Blakely and Señor Chester had sat far into the night talking over the situation, and it had struck midnight before they arrived at the conclusion that it would be inflicting a needless shock to inform Señora Ruiz of Juan’s report of her husband’s death until some sort of confirmation had been obtained. Fate, however, took the painful task out of their hands. The gossipy servants who had heard Jose’s lamentations lost no time in conveying the news to the estancia of Señor Pachecho. Señora Ruiz received the report of her husband’s death bravely enough while the servants were in the room, but after they had left she fell in a swoon and speedily became so ill that the old doctor at Restigue had to be routed out of bed and driven at post haste in a rickety volante to Don Pachecho’s home.

After a hasty snack—a la Espagnole—the real breakfast in the tropics not being taken till eleven o’clock or so—the master of La Merced and Blakely mounted their horses and set out at top speed for Greytown.

“I’ve got my own ideas of welcoming the boys to Nicaragua,” confided Mr. Chester to his overseer as they put spurs to their mounts, “I ordered a bonga to be in readiness for us as soon as the Aztec arrived. I guess a trip through the surf in one of those will astonish them, eh?”

“I should jolly well think so,” replied the Hon. Jimmie, screwing his monocule more firmly in his eye.

The young Britisher was immaculate in khaki riding breeches, long gray coat and yellow puttees. The admired and feared eyeglass, to which he owed so much of his power over the natives, was gleaming firmly from his face, nor did the rapid pace at which the rough-gaited horses were urged over the road, affect its equilibrium. To save time Mr. Chester had elected to take a trail instead of the main road. By doing this they cut off at least ten miles of the distance. It was a wild looking cavalcade that galloped along through clouds of dust over the none too sure footing of the rock-strewn trail. Behind Mr. Chester and Jimmie rode old Matula and the redoubtable Jose. The latter proudly wore about his classic brow a white bandage—in token of his being a hero and wounded. Both Jose and Matula led after them extra ponies for the use of the boys in the ride back to La Merced.

Bringing up the rear was a particular friend of Jimmie’s mounted on a razor-backed, single-footing mule that somehow managed to get over the ground as fast as the other animals and without any apparent exertion. Jose’s friend was a peculiarly villainous-looking old Nicaraguan Indian, who eked out a scanty living at rubber cutting—that is, slashing the rubber trees for their milk and carting the product in wooden pails to the coast.

He had arrived at the ranchero a few days before and not finding Jose there, the patriot being at the front, had just hung around after the easy fashion of the country to wait for him. The clothes of this old scarecrow, who by the way answered to the name of Omalu, consisted of coffee bags all glued over with the relics of countless tappings of the rubber tree. As he bestrode his mule his legs stuck out from his gunny bag costume like the drumsticks of a newly-trussed fowl.

Both Mr. Chester and Jimmie were armed. The former carried, besides his navy pattern Colt, a cavalry carbine slung in a holster alongside his right knee. Jimmie had strapped to a brand new cartridge belt an automatic revolver of the latest pattern. In addition to these weapons Jose and Matula carried their machetes, without which a native of any Central American country will in no wise travel, and old Omalu regarded, with a grin of pride on his creased face, his ancient Birmingham matchlock—commonly known as a gas-pipe gun.

As the cavalcade clattered into the dusty palm-fringed port of Greytown, with its adobe walls and staring galvanized iron roofs, the first launch from the Aztec was just landing passengers at the end of the new, raw pine wharf recently built by the steamship company. Before this all landings had been made through the surf, as Mr. Chester intended to land the boys.

The owner of La Merced and his party halted to watch the group of new arrivals making its way down the pier. Among the first to put his foot ashore was the black-bearded man who had such a narrow escape of missing the steamer in New York.

He looked very different now, however, except for his heavy face and suspicious quick glances. He wore spotless white ducks, of which he had purchased a supply a few days before, at the first tropic port of call the Aztec made. On his head was a huge Panama hat of the finest weave. In his hand he still gripped the black leather bag that he had caused such a fuss about in New York. It looked very incongruous in contrast to his fresh South American attire.

“General Rogero!” exclaimed Mr. Chester, as the black-bearded man came abreast of the little party. Hearing the name the person addressed looked up quickly.

“Ah, Señor Chester,” he exclaimed, displaying a glistening row of teeth beneath his heavy moustache, “how strange that you should be the first person I should meet after my little voyage to your delightful country. How goes it at the Rancho Merced?” He seemed purposely to avoid the important events that were transpiring.

Mr. Chester assured him that rarely before had the season promised better. The rains had ceased early and the crops looked as if they would be exceptionally heavy.

While they talked a barefooted messenger from the telegraph office in the iron railroad station slouched up to them.

“For you, General,” he said, saluting as he handed the bearded man a pink envelope.

With a swift “pardon” Rogero ripped open the envelope the messenger had handed him. From the time it took him to read it it was of greater length than the ordinary wire and he raised his eyebrows and exclaimed several times as he perused it.

When at length he looked up from it his face had lost the almost smug expression it had worn before. In its place there had come a manner of contemptuous command very thinly veiled by a sort of sardonic politeness.

“As you probably know,” he said, “and as this telegram informs me, the insurgent forces under the renegade Estrada were beaten back two days ago at El Rondero,” he looked insolently from under his heavy lids at the American planter to observe the effects of his words upon him.

For all the effect it had on Mr. Chester however, the words might as well have been directed at a graven image.

“Well?” he said, taking up the thinly disguised challenge flung at him by Rogero.

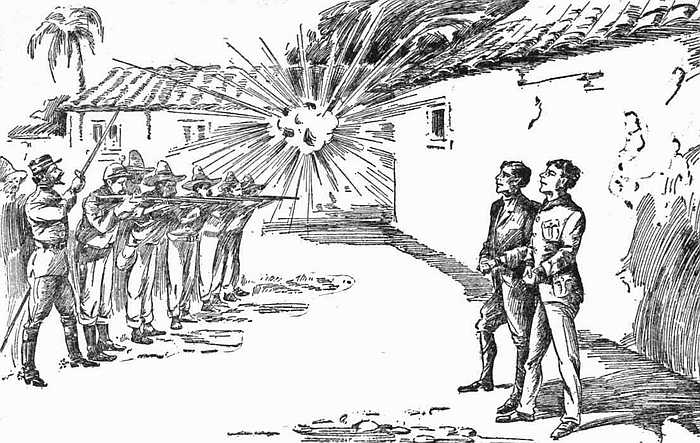

“Well,” sneered Rogero, “I simply thought it might be of interest to you to tell you that you are regarded at Managua as renegado. I may also inform you that to-day at sunrise the two captured Americans suspected of being connected with the revolutionaries were shot down like——”

Whatever General Rogero might have been going to add he stopped short as Mr. Chester bent his angry gaze on him.

“What!” exclaimed the latter, “shot down without a trial—without an opportunity to explain. Zelaya will suffer for this.”

“That remains to be seen,” sneered Rogero, selecting a cigarette from a silver case and lighting it with calm deliberation. “What I have to say to you is in the nature of a warning, Señor. ‘Verbum sapiente,’ you know.”

“I can dispense with your advice, Señor,” cut in Mr. Chester.

“At present perhaps—but we may meet later and under different circumstances. Remember, Señor, that General Rogero of President Zelaya’s army shows no mercy to those who choose to ally themselves with dogs of rebels. Whether they are American citizens—or British,” he added with a look of scorn at Jimmie, “it makes no difference. A bullet at sunrise answers all questions.—Adios Señores.”

He raised his hat with an abrupt gesture, and with a sharp “Venga,” to an obsequious orderly from the barracks, who had just arrived with a horse for him, the general swung himself into the saddle and rode off to the Hotel Gran Central de Greytown.

As the general cantered off in a scattering cloud of dust, a youth who had landed from the launch at the same time, stepped up to Mr. Chester and his companion. He looked as if he might have walked off the vaudeville stage. Over one shoulder was slung a camera, from the other depended a canteen. A formidable revolver was strapped at his waist, and a pith helmet with a brilliant green cumer-bund sat low on his reddish hair. While the general had been uttering his sinister threats this figure had been busy taking snapshots of everything from the gallinazos or carrion buzzards that sat in long rows along the ridges of the galvanized roofs to the old women under huge umbrellas, who dispensed evil-looking red and yellow candy from rickety stands.

“I beg your pardon,” he said, placing his hand on the pommel of Mr. Chester’s saddle. “Would you mind telling me who that gentleman is with whom you have just been speaking?”

As he raised his face he disclosed a plump, amiable countenance ornamented by a pair of huge round spectacles.

“I know this is unusual,” he hurried on apologetically, “but I’m Barnes—Billy Barnes of the New York Planet,—correspondent, you know.”

“Well, Mr. Barnes, if you are a correspondent you will have a lot of opportunities to meet General Rogero before this little trouble is over,” replied Mr. Chester, in an amused tone.

The effect of this reply on Mr. Barnes of the Planet, was extraordinary. He blew his cheeks out like a frog and executed a sort of double shuffle. He gazed at Mr. Chester in a portentous way for a few seconds and then sputtering out:—“You say that’s General Rogero?” then, with the cryptic words:

“Joseph Rosenstein, diamond salesman, eh?—oh Lord, what a story!” he dashed off in the direction the general’s horse had vanished.

“That young man is either insane or the sun has gone to his head,” commented Mr. Chester, as both he and Jimmie watched young Mr. Barnes’s fat little legs going like pistons bearing him toward the Hotel Gran Central.

“He’s a jolly queer sort of a cove,” was the amiable Jimmie’s comment, “a bit balmy in the crumpet, I should say.”

Any explanation of the meaning of “Balmy in the crumpet” on Jimmie’s part, was cut short by a native who ran from midway down the wharf and approaching Mr. Chester, rapidly muttered a few words of corrupt Spanish.

“He says the bonga is ready,” said Mr. Chester, turning to Jimmie—“come on. Remember I haven’t seen my boys for a year or more.”

They hurried down the wharf leaving Matula, Jose and old Omalu behind to watch the horses. Alongside the pier, riding the heavy swells like a duck, lay a peculiar type of boat about thirty feet long, called by the Nicaraguans, a bonga. It was carved out of a solid log of mahogany and painted a bright glaring red inside and out. They clambered down into it by a ladder formed of twisted jungle creepers and a few minutes later were skimming the smooth green swells that lay between them and the Aztec.

The bonga, urged along by her two peaked sails, ran alongside the Aztec, a quarter of an hour later. The boys were leaning over the rail looking very natty in neat, white duck suits and Panama hats, and the meeting after Mr. Chester and Blakely had clambered aboard up a hastily thrown Jacob’s Ladder, can be better imagined than described.

The first greetings over and the boys having been introduced to Blakely, the conversation naturally turned to the Golden Eagle. Led by Frank and Harry, Mr. Chester and the overseer proceeded to the fore deck where the crew of the Aztec assigned to that duty were making fast a sling to hoist the first of the blue boxes over into the lighter that lay alongside the steamer.

“You see,” explained Frank to his interested listeners, “that we have taken good care to cage our Golden Eagle securely. I suppose, father, that you would like to hear a few details of its construction. Well, then, ladies and gentlemen,”—adopting a grandiloquent showman’s manner—“the Golden Eagle is a biplane machine—that is to say, that she has a double set of planes one above the other. They have a spread of fifty-six feet by six and are covered with balloon silk of a special quality lacquered over with several coats of a specially prepared fire and water composition.

“She can lift a weight of two hundred pounds in addition to the three passengers she is capable of carrying. I believe that we will be able before long to stay up in the air for a sustained flight of two hundred miles or more. Already we have made a flight of a hundred and fifty miles and with the new twin propellers that we have adjusted I think we can make the longer distance easily.

“Our engine is fifty horsepower of what is known as the opposed type and every bit of it made in an American shop. It ‘turns up’ twelve hundred revolutions a minute. We rarely run it that speed, however. The gasolene and the water for cooling the cylinder jackets are suspended in tanks under the deck-house. A pump circulates the water through the cylinder jackets and into a condenser where it is cooled off and is ready to be forced through the cylinders again. The lubricating oil is fed also by a force system which is much more reliable than the gravity method particularly in an air-ship where there is a tendency to pitch about a lot in the upper air currents.

“The frames upon which the covering of the planes is stretched are formed of an alloy of aluminum and bronze which makes an exceptionally light and strong material for the purpose. We put a few ideas of our own into the Golden Eagle when we built her, among them being an improved bird-like tail which makes her handle very readily even in heavy weather.

“And—Oh, yes, I almost forgot the wireless plant. That is really the most unique feature of our craft. We carry our aerials, as the long receiving wires are called, stretched across the whole length of the upper plane and the receiving and sending apparatus is right handy to the operator’s right hand. We have a double steering wheel fitted tandem, so that anyone sitting behind the operator can handle the rudder while he is busy at the wireless.

“In the pilot-house, as we call it, but it is really more a sort of cockpit in the deck-house, are fitted small watertight mahogany boxes which contain our navigating instruments and we have a brass binnacle boxing in a spirit compass which is lighted at night by the current from a miniature dynamo which also supplies power for a small but powerful searchlight.

“Then there is the ration basket. It weighs but fifty pounds full, but it carries enough provisions for three persons for five days. In it also are three pairs of thin blankets made of a very light but warm weave of material and a water-filter. It contains, too, some medicines and bandages and lotions in case we have a smash-up. So you see,” concluded Frank with a laugh, “we have a pretty complete sort of a craft.”

After good-byes had been said to the Aztec’s captain and a few of their fellow-passengers who still remained on board, and the last of the dozen cases containing the Golden Eagle had been lowered into the lighter, the little party descended the Jacob’s Ladder and took their places in the bonga. While they had been on board one of the brown-skinned fishermen who manned her had rigged up a sort of awning astern with a spare sail, and this gave the voyagers a welcome bit of shade. With a cheer from the boys her crew shoved off and the bonga heeling to the breeze headed for the palm-fringed shore.

“About time they put about and ran up to the wharf, isn’t it?” asked Harry as the bonga scudded along so close to the shore that the roar of the heavy surf as the big waves broke on the yellow beach could be distinctly heard.

“Here’s where you are going to get a new experience,” laughed Mr. Chester, “I want to see whether such bold air sailors as you boys can stand shooting the surf without being scared.”

“You don’t mean to say that we are going to land on the beach?” gasped Harry.

“That’s just what I do,” cheerfully replied his father. “In a few minutes you’ll see something that will show you that all the wonders of the world aren’t monopolized by New York.”

The men in the bonga were lowering the sails as he spoke and when they had them tied in gaskets each took an oar while the captain ran to the stern with a long sweep.

The men rowed slowly toward the shore till they were almost hurled bow on into the tumbling surf. Suddenly, at a cry from the man in the stern, they stopped work with their oars and the bonga tossed up and down on the racing crests of the big waves while they “backwatered.”

All at once the man with the steering oar, who had been watching for a large wave to come rolling along, gave a loud command. The rowers fell furiously to work. The boys felt the bonga lifted up and up on the crest of the big combers and a second later they were swept forward, it seemed at a rate of sixty miles an hour. The surf broke all about the bonga, but she hardly shipped a drop.

As the long narrow craft raced into the boiling smother of white foam her crew leaped out in water almost up to their necks and fairly rushed the craft up the beach before the next roller came crashing in.

“Well, that beats shooting the chutes, for taking your breath away,” remarked Harry as the party strolled along under a palm-bordered avenue on their way to the hotel where they were to lunch. The dripping crew of the bonga followed them carrying the boys’ smart, new baggage on their heads.

The Hotel Grand Central was a long building with a red-tiled roof and the invariable patio in the center off which the room opened. The boys were delighted with the place. In the middle of the patio, in a grove of tropical plants, a cool fountain plashed and several gaudy macaws were clambering about in the branches of the glistening greenery. The hot dusty street outside with its glaring sun and blazing iron roofs seemed miles away.

As they were about to turn into the sala, in which their meal was to be served, a man bustled out and almost collided with them. It was General Rogero.

“Ah, Señor, we seem fated to encounter each other to-day,” he exclaimed with a flash of irritation as his eyes met Mr. Chester’s.

The next moment he had started back with a quick: “peste!” as his dark gaze fell on the boys.

“Why!” exclaimed Harry, “that’s the fellow who came down on the ship. The man who said he was a diamond salesman and that he had a lot of stones in that black bag! Do you know him, father?”

“Know him?” repeated Mr. Chester in a puzzled tone as Rogero whisked scowling out of sight into an adjoining room.

“He was a mysterious sort of cuss,” chimed in Frank, “kept to himself all the way down and had his meals in his cabin.”

“Perhaps he had a good reason to,” smiled Mr. Chester; “your diamond salesman is General Rogero of the president’s army.”

As he spoke and the two boys fairly gasped in astonishment at this sudden revelation of the true character of the man with the black bag, Billy Barnes came hurrying up.

“Hello, my fellow-passengers,” he exclaimed heartily; “hello, Frank! hello, Harry!”—it was characteristic of Mr. Barnes, that although he had met the boys for the first time on the steamer he was calling them by their first names the second day out—“as I hinted to your father an hour or so ago, I’ve run into the biggest story of my career.”

“You rushed off in such a hurry that I could hardly call it even a hint,” smiled Mr. Chester.

“You’ll get jolly well laid up, Mr. Barnes, if you go rushing about like that in this climate—what?” put in Blakely.

“I beg your pardon, sir, really,” burst out the impulsive Billy contritely, addressing Mr. Chester, “but you know when a newspaper man gets on the track of a good story he sometimes forgets his manners. But you will be interested in my morning’s work.”

“Here’s what I’m digging on and if it isn’t a snorter of a story never let me see New York again.”

“Well, what is it, Billy?” asked Harry, “come on, never mind the fireworks—let’s have it.”

“Just this;” proudly announced the reporter, “General Rogero has only two fingers on his right hand.”

“Yes?” from the boys in puzzled tones.

“Well, what of it?” from Mr. Chester.

Billy was evidently artist enough to keep his listeners in suspense for he went on with great deliberation.

“You remember that when he was ‘a diamond salesman,’ on board the Aztec that we hardly ever saw him?—well, there was a reason, as the advertising men say. What was that reason? you ask me. Just this; that he didn’t want any one to get wise that he was minus three of his precious digits.

“Why for?—Because the man who killed Dr. Moneague in New York, was shy on his hands in the same way—now do you see!” triumphantly demanded the reporter.

“If our amiable friend Rogero isn’t the same man who murdered Moneague in New York I’ll eat my camera, films and all,” he concluded.

“It doesn’t seem to me that you have any proof on which you can base such a serious accusation,” said Mr. Chester. “Rogero is a desperate man and an unscrupulous one, but I do not believe that even he would deliberately commit such a crime.”

“Don’t you, sir?” contradicted Billy, “well, I do. From what I’ve observed of him, he’d stop at nothing if he had an end to gain. The thing in this case though is, what was his motive for killing Dr. Moneague, except that Moneague, so the police discovered, was an agent of the revolutionists down here?”

Like a flash the recollection of what Don Pachecho had told him about the bit of parchment on which was traced the secret of the lost Toltec mines crossed Mr. Chester’s mind. He hurriedly gave his interested auditors an outline of what he knew about the clue to the treasure trove.

“Rogero’s the man then for twenty dollars!” excitedly cried Billy. “He had the thing in that black bag he guarded so carefully. If I only could get hold of it we’d have his neck in the halter in a brace of shakes. I’ve a good mind to try. The first thing I’m going to do, though, is to flash a bit of message to New York—to No. 300 Mulberry Street—and tell my old friend Detective Lieutenant Connolly that I think a run down here would result in his turning up something interesting. Anyhow——,” the reporter was continuing, when he was cut short by the sound of a shot from outside and a loud cry of pain. The startled party hurried through the sala and out into the street.

“A shot means a story;” remarked Billy to his camera as he adjusted it ready for action while he hurried along after the others.

In front of the hotel an excited crowd was clustered about a man who lay in the dust. He was evidently badly wounded if not dead. Near by, a sneer on his evil face, stood Rogero, his still smoking pistol in his hand. As Mr. Chester and the boys hurried up he turned to them and exclaimed:

“You see, Señor, that it is not safe to be a revolutionist in these days.”

“Why it’s poor Juan!” cried Mr. Chester as he bent over the man who had been shot. “Good God, he’s dead!” he exclaimed a second later after a brief examination of the prostrate figure.

“Yes; one of your servants I believe,” remarked Rogero carelessly, “the dog was pointed out to me as being a runaway from Estrada’s army and, when I called him to me to give him a little wholesome advice, he started to run off so I was compelled in the interests of discipline to shoot him.”

There was no more emotion in his voice than if he had been speaking of some ordinary event of life.

“This is a coward’s trick!” exclaimed Mr. Chester angrily, “this man was my servant and any complaint you had against him you should have referred to me.”

Rogero lightly flicked some ash off the cigarette he was smoking.

“I should be more temperate in my language, Señor, if I were you,” he said.

“I am an American citizen, sir,” replied Mr. Chester; “the flag of my country floats over that consulate.” He pointed to a neat, verandered building a few blocks away. “I shall see that you are made to answer for this wanton crime.”

“I am afraid that you will have to defer such action for the present,” sneered Rogero, as a file of ragged Nicaraguan soldiers came running from the barracks and, after saluting him respectfully, fell in behind him with fixed bayonets.

“This city is under martial law and I should advise you to be circumspect in your behavior. A suspected insurgent sympathizer is on dangerous ground in these days.”

“By the way,” he went on viciously, “I am afraid that I shall have to interdict the orders you have given to have that celebrated air-ship,”—there was a bitter irony in his tones that made the boys clinch their fists, “conveyed to your hacienda. I am of the opinion that air-ships in the hands of revolutionists sympathizers come under the head of contraband of war and I intend to have this particular one destroyed.”

The effect on Harry and Frank of these words was magical. The elder brother sprang angrily forward although his father and Blakely tried to hold him back.

“You mean you would dare to destroy the property of non-combatant American citizens?” he demanded, his blood aboil.

“I don’t talk to boys,” was Rogero’s contemptuous reply.

“Well, you’ll have to talk to us,” angrily chimed in Harry coming forward, “if you put a finger on the Golden Eagle, or harm her in any way you will find that the United States’ government resents any insult or injury to her citizens in a way that you will remember.”

So excited were the boys at the dastardly threat of Rogero, and so thunderstruck were their father and Blakely at the man’s brutal arrogance that none of them had noticed Billy Barnes who had been standing behind the party. Now he stepped up, with his camera, bellows pulled out and ready for action. Rogero was standing defiantly, his hand on his sword-hilt. For the first time the boys saw his right hand.

There were two fingers missing!

“Just hold that pose for a second, General,” exclaimed Billy, his finger on the button of his machine. Rogero turned with a snarl as the button clicked and his image was irrevocably fixed on the film.

“It will be a beautiful picture,” remarked Billy amiably. “You see the light was very good and the lamentable fact that you are shy two fingers will be clearly shown, I hope, in the print I intend to make at the earliest opportunity.”

“You dog of a newspaper spy,” snarled Rogero, his face a pasty yellow and fear in his eyes, “I know you. You are a sneaking reporter. We don’t like such renegades as you in my country. We have a way of dealing with them, however, that usually causes them to cease from troubling us.”

He raised his hand to his throat and gave an unpleasant sort of an imitation of the “garrotte” which is the instrument of execution in most Latin-American countries.

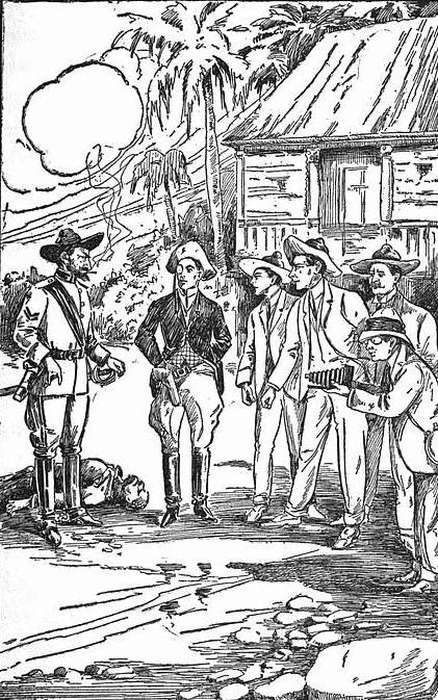

“JUST HOLD THAT POSE A SECOND, GENERAL.”

“And we in the States have also got a way of dealing with men like you,” said Billy meaningly. “Now,” he went on in a low voice, stepping close to Rogero, “if you harm that aeroplane in any way I’ll forward the picture, I just took to Detective Connolly of the New York Central Office, and I think he can have a very interesting time with it tracing your movements in New York before the murder of Dr. Moneague!”

If he had been struck full in the face the effect on Rogero could not have been more magical. He opened his dried lips as if to speak, but no sound came. In his eyes there was a hunted look.

“I’ll have you——,” he began when he at last found his voice.

“You’ll have nothing,” replied Billy cheerfully, “because you don’t dare. Now, then; tell these boys they can have their aeroplane unharmed. Write them an order—here’s my pad and a fountain pen—don’t forget to give them back.”

Rogero snarled like a cornered tiger, but he took the pen and scrawled a passport in Spanish on Billy’s pad.

“Take your wonderful flying machine then, and I only hope you break your necks,” he muttered. With an evil look at Billy which did not at all seem to worry that amiable young gentleman who merely winked knowingly in reply, he turned on his heel and strode off followed by his soldiers.

“By Jove, you American pressmen have a high-handed way of doing things, I must say,” remarked Blakely. The boys, too, were much delighted and amused and congratulated Billy warmly on his successful bit of strategy. Mr. Chester, however, by no means took the matter so lightly. After he had given orders that the body of the unfortunate Juan be properly cared for and sent back to La Merced for burial, he turned to young Barnes.

“My boy,” he said, “we are not in America now, and in the present state of the country Rogero can be a very dangerous man.”

“He ought to be shot,” indignantly cried Harry.

“Or hanged,” put in Frank.

“Both,” concluded Billy, with conviction.

“Perhaps,” said Mr. Chester, as he headed the little group into the hotel once more, “but in Nicaragua the law of might prevails and that man means mischief.”

As he uttered the last words in a grave tone there came a rattle of hoofs far down the street, and the next minute a horseman flashed by the hotel in a cloud of yellow dust. He spurred his horse desperately up to the barracks and, as he drew rein, Mr. Chester and the boys saw Rogero come out on the balcony and the messenger standing in his stirrups, hand him an envelope.

“News from the front,” commented Mr. Chester. Rogero disappeared for a few minutes and when he came out again he handed the messenger another envelope, evidently containing a reply to the despatch he had just received. The man wheeled his horse almost on its haunches and spurred down the street again.

“What is it?” shouted Mr. Chester in Spanish to him as he dashed by the hotel riding as if his life depended on speed.

“Another great victory,” he shouted reining his sweating horse in for an imperceptible fragment of time.

As the clatter of his horse’s hoofs died away in the direction of the mountains there was a great commotion in the barracks. Bugles sounded and men ran about with horses, arms and bundles, in the confusion that characterizes improperly-disciplined troops. After about half an hour of this frenzied preparation the troops, some two hundred in number, with Rogero and his dark-skinned staff officers at their head with the blue and white “colors”; fell awkwardly in line and to the music of a crazy band with battered, dirty instruments began their march to the front.

Their way led by the hotel where the boys stood gazing with amusement and some pity at their first sight of a Central American army on the march. Some of the troopers were not much bigger than the newsboys they had left behind in the New York that now seemed so far away. These little fellows tottered along under the weight of haversacks and heavy Remington rifles, keeping step as best they could with their elders. Several of the soldiers carried gamecocks under their arms and others had guitars and mandolins slung over their shoulders; one man even carried a bird in a wooden cage.

Rogero’s face bore a deep scowl as he rode by surrounded by his excited staff officers. His eyes were downcast but he raised them as he passed the little group in front of the Grand Central. There was a sinister gleam in them like that in the leaden orbs of a venomous serpent.

“Adios, señors,” he sneered, leaning back in his saddle, “we shall meet again and I shall have the pleasure, I hope, of introducing some of you to our Nicaraguan prisons.”

Wagons for the transportation of the packing cases containing the Golden Eagle, and for the boys’ baggage had been secured by old Matula earlier in the day and when the Chester party arrived at the wharf, late in the afternoon, he had made such an impression on the native workers by his imperious commands and promises of extra money from the Señor Chester for fast work, that they found everything in readiness for the journey back to the plantation. The boys were delighted with their ponies, spirited little animals as quick as cats on their feet and able to travel over the rough mountain roads like goats.

The wagon was drawn by a team of bullocks hitched to the pole by a heavy yoke of wood, with the rough marks of the axe still upon it.

“Well, we really are in a foreign country at last,” exclaimed Harry as his eyes fell on the primitive-looking wagon and its queer motive power.

In spite of old Matula’s by turns imploring, threatening and wheedling persuasions it was almost dark when the expedition was ready to make a start for the plantation. There was a full moon, however, and the moonlight of the tropics in the dry season is a very different thing to the pallid illumination of the northern Luna. As the Chester party, headed by the boys on their ponies, wound through the streets of Greytown and began the long steady climb to La Merced, a radiance like electric light flooded the way and showed them every twig and leaf as clearly as if it had been day. Everywhere, too, the darker shadows were spangled with brilliant fireflies.

They reached the plantation about midnight and found that the servants had made everything ready for their reception. The boys were delighted with the picturesque reception the hands gave them. Every man, woman and child had a torch and the sight of these flickering about in the moonlight long before they reached their destination resembled a convention of huge lightning-bugs.

Inside the main sala there was a tempting meal in the native style laid out. There was huge grapefruit and custard apples, a fruit filled with real custard, crisp bread-fruit roasted to a turn, fragrant frijoles, the national dish of the Latin-American from Mexico to Patagonia, and several kinds of meat and salted fish all cooked in the best style of old Matula’s wife, who waited on them.

“Well, this beats Delmonico’s,” remarked Billy, who at Mr. Chester’s hearty invitation had made one of the party. “I always had an idea that you people down here lived like savages,” he laughed, “but here you are with a layout that you couldn’t beat anywhere from New York to the coast.”

Billy’s simple-hearted admiration of everything he had encountered on the estancia caused Mr. Chester much amusement. Billy proved his appreciation of everything by sampling all the dishes in turn including a dish of red peppers that caused his temporary retirement in agony.

“Jimminy crickets, I felt as if I had a three alarm fire in my department of the interior,” was the way he explained his feelings after he had swallowed a gallon of water, more or less, to alleviate his sufferings.

After their exciting day the boys slept like tops, although their dreams were a wild rehash of the novel experiences they had gone through. Frank dreamed that Rogero in an airship fashioned like a bonga was pursuing them through space and that although they speeded up the Golden Eagle to her fastest flight, the evil-faced Nicaraguan gained on them rapidly. He had just run the prow of his queer air-craft into the Golden Eagle’s stern and Frank felt himself falling, falling down into a huge sort of lake of boiling surf when he awoke to find it was broad daylight, and the cheerful daily routine of the plantation going busily on as if the events of the day before had been as unreal as his dream. Springing out of bed, Frank aroused Harry. The younger boy had just about rubbed the sleep out of his eyes when their father came into the room.

“Come on boys,” he said, “and I’ll show you how we take our morning bath down here.”

The boys slipped on bath-robes and thrust their feet into slippers. When they were ready Mr. Chester led them out to a small building with latticed sides a short distance from the house. Inside was a cement-lined pool about twenty feet in length by fifteen in width with a depth that varied from five feet at one end to seven at the other. It was full of sparkling water that ran into it from a mountain stream on one side, and was piped back into the bed of the brook, again after it had flowed through Mr. Chester’s unique bathroom.

With a loud whoop Harry was just about to jump into the inviting looking bathing-place when Mr. Chester stopped him.

“Look before you leap, Harry,” he cautioned, “every once in a while a tarantula or a snake or a nice fat scorpion takes a fancy to a bath, and tumbles in here and they are not pleasant companions at close range.”

An investigation showed, however, that there were none of the unpleasant intruders Mr. Chester had mentioned in the bath that morning, at least, and the two boys swam about to their hearts’ content, and after dressing came in for breakfast as delightful as their meal of the previous night in its novelty and variety.

Breakfast despatched of course the first thing to do was to superintend the unpacking of the Golden Eagle. The bullock cart had been taken down to a cleared spot not far removed from the barracks of the laborers, and a squad of brown-skinned men were already at work when Frank and Harry strolled down there setting up a sort of shelter, thatched with palm leaves under which the boys might work without being in danger of sunstroke.

Everybody on the plantation found some excuse to pass by the shelter that morning while the boys, and three or four envied laborers unpacked the Golden Eagle, and began to put the sections in place. A feature of the ship of which the boys were very proud was the ease with which, by a system of keyed joints, their beautiful sky-ranger could be taken apart or put together again very quickly. Under Frank and Harry’s coaching even the Nicaraguan laborers, none of the brightest of humankind, got along very fast, and by the time the second breakfast, as it is called, was ready the frames for the planes were in place and the trough-like cockpit or passenger car ready in position to have the piano wire strands of immense tensile strength that connected it to the steel stanchions of the planes screwed into place with delicate turnbuckles made especially for the Golden Eagle.

After lunch the work went on apace. The balloon-silk coverings of the planes were fitted with tiny brass ringed holes through which they were threaded on to the frames by fine wire. This was a tedious business and Frank and Harry did it themselves, not caring to trust so delicate an operation, and one which required so much patient care, to the good-natured, easy-going Nicaraguans, who would have been as likely as not to have scamped the job and left several holes unthreaded. As the whole pressure of the weight of the car and its occupants, fuel and lubricants was to be borne by these planes it can readily be seen why the boys placed so much importance on doing a good thorough job.

It took till sunset to complete this task and the boys were tired enough not to be sorry that their work was done when the big bell that called the laborers in from the banana groves began to clang.

In the work on the Golden Eagle the boys had been very materially aided by Billy Barnes, who photographed the craft from every possible and impossible point of view and insisted on Frank snapping a picture of him sitting at the steering wheel.

“It’s as near as I’ll ever get to steering her, I guess,” he explained, “I haven’t got the head for these things that you chaps have.”

It was Billy Barnes, too, who reported that evening in great excitement that while he was walking along the porch he had seen a big spotted cat “loafing around.”

“That wasn’t a cat,” laughed Mr. Chester, “that was an ocelot and if you think you can qualify as a Nimrod we will go out after supper and try and get a shot at it. They are bad things to have around the place—not that they are really dangerous, but they steal chickens and the men are scared of them and spend most of the day looking out for what Billy calls a ‘big cat,’ instead of doing their work.”

“I don’t know what or who Nimrod is,” replied the good-natured reporter, “but I sure would like to get a shot at that ossy—what do you call it?”