Project Gutenberg's The Curiosities of Heraldry, by Mark Antony Lower This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Curiosities of Heraldry Author: Mark Antony Lower Release Date: February 22, 2012 [EBook #38951] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CURIOSITIES OF HERALDRY *** Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

WITH

Illustrations from Old English Writers.

BY

MARK ANTONY LOWER,

AUTHOR OF “ENGLISH SURNAMES,” ETC.

WITH NUMEROUS WOOD ENGRAVINGS,

From Designs by the Author.

LONDON:

JOHN RUSSELL SMITH,

4, OLD COMPTON STREET, SOHO.

MDCCCXLV.

C. AND J. ADLARD, PRINTERS, BARTHOLOMEW CLOSE.

Little need be said to the lover of antiquity in commendation of the subject of this volume; and I take it for granted that every one who reads the history of the Middle Ages in a right spirit will readily acknowledge that Heraldry, as a system, is by no means so contemptible a thing as the mere utilitarian considers it to be. Yet, notwithstanding, how few are there who have even a partial acquaintance with its principles. To how many, even of those who find pleasure in archæological pursuits, does the charge apply:

“—neque enim clypei cælamina norit.”

Two hundred years ago, when the study of armory was much more cultivated than at present, this general ignorance of our ‘noble science’ called forth the [Pg iv]censure of its admirers. Master Ri. Brathwait, lamenting it, says of some of his contemporaries:

“They weare theire grandsire’s signet on their thumb,

Yet aske them whence their crest is, they are mum;”

and adds:

“Who weare gay coats, but can no coat deblaze,

Display’d for gulls, may bear gules in their face!”[1]

This invective is perhaps a little too severe, yet it is mildness itself when compared with that of Ranulphus Holme, son of the author of the ‘Academy of Armory,’ who declares that unless the reader assents to what is contained in his father’s book he is

“neither Art’s nor Learning’s friend,

But an ignorant, empty, brainless sot,

Whose chiefest study is the can and pot!”

Now, though I would by no means place the objector to Heraldry upon the same bench with the devotee of Bacchus, nor even upon the stool of the dunce, yet I hope to make it appear that the study is worthy of more attention than is generally conceded to it.[2] At the same time I wish it to be distinctly understood that I do not over-rate its importance. “The benefit arising from different pursuits will differ, of course, in[Pg v] degree, but nothing that exercises the intellect can be useless, and in this spirit it may be possible to study even conchology without degradation.”

Many persons regard arms as nothing more than a set of uncouth and unintelligible emblems by which families are distinguished from one another; the language by which they are described as an antiquated “jargon;” and both as little worthy of an hour’s examination as astrology, alchemy or palmistry. This is a mistake; and such individuals are guilty, however unintentionally, of a great injustice to a lordly, poetical, and useful science.

That Heraldry is a lordly science none will deny; that it is also a poetical science I shall shortly attempt to prove; but there are some sour spirits who know not how to dissever the idea of lordliness from that of tyranny, and who “thank the gods for not having made them poetical.” These, therefore, will be no recommendations of our subject to such readers; but should I be able to show that it is a useful science, what objections can those cavillers then raise?

I purpose to give a short dissertation on the utility of Heraldry, but first let me say a few words on the poetry of the subject. Do not the ‘Lion of England,’ the ‘Red-Cross Banner,’ the ‘White and Red Roses,’ the ‘Shamrock of Ireland,’ and ‘Scotia’s barbed Thistle’ occupy a place in the breast of every patriot? and what are they but highly poetical expressions? Do not the poetry of Chaucer and Spenser and Shakspeare, not to mention our old heroic ballads and the pleasant legends[Pg vi] of a Scott, abound with heraldrical allusions? Tasso is minute, though inaccurate, in the description of the banners of his Christian heroes; he was far from despising blazon as a poetical accessory. And, lastly, see how nobly the stately Drayton makes the ‘jargon’ of Heraldry chime in with his glorious numbers:

“Upon his surcoat valiant Neville bore

A SILVER SALTIRE upon martial red;

A LADIE’S SLEEVE high-spirited Hastings wore;

Ferrers his tabard with rich VAIRY spred,

Well known in many a warlike match before;

A RAVEN sate on Corbet’s armed head;

And Culpeper in SILVER ARMS enrailed

Bore thereupon a BLOODIE BEND ENGRAILED;

The noble Percie in that dreadful day

With a BRIGHT CRESCENT in his guidhomme came;

In his WHITE CORNET Verdon doth display

A FRET OF GULES,” &c.

Barons’ War, B. 1, 22, 23.

I now proceed to show that Heraldry is a useful science. It has already been said that nothing which calls into exercise the intellectual powers can be useless. But it may be said that there is an abundance of studies calculated more profitably to exercise them. Granted: but it should be remembered that, as there is a great diversity of tastes, so there is a great disparity in the mental capacities of mankind. Heraldry may therefore be recommended as a study to those who are not qualified to grasp more profound subjects, and as a source of amusement to those who wish to relieve their[Pg vii] minds in the intervals of graver and more important pursuits. To either class a very brief study will give an insight into the theory of heraldry, and a competent knowledge of the terms it employs.

The nomenclature of Heraldry is somewhat repulsive to those who casually look into a treatise on the subject, and often deters even the unprejudiced from entering upon the study; but what science is there that is not in a greater or less degree liable to the same objection?

A recent writer observes: “The language of Heraldry is occasionally barbarous in sound and appearance, but it is always peculiarly expressive; and a practice which involves habitual conciseness and precision in their utmost attainable degree, and in which tautology is viewed as fatally detrimental, may insensibly benefit the student on other more important occasions.”[3]

But Heraldry is useful on higher grounds than these, and particularly as an aid to the right understanding of that important period of the history of Christendom, the reign of feudalism. An eminent French writer, Victor Hugo, declares that “for him who can decipher it, Heraldry is an algebra, a language. The whole history of the second half of the middle ages is written in blazon, as that of the preceding period is in the[Pg viii] symbolism of the Roman church.” To the student of history, then, Heraldry is far from useless.

The sculptured stone or the emblazoned shield often speaks when the written records of history are silent. A grotesque carving of coat or badge in the spandrel of some old church-door, or over the portal of a decayed mansion, often points out the stock of the otherwise forgotten patron or lord. “A dim-looking pane in an oriel window, or a discoloured coat in the dexter corner of an old Holbein may give not only the name of the benefactor or the portrait, but also identify him personally by showing his relation to the head of the house, his connexions and alliances.”[4] The antiquary and the local historian, then, possess in Heraldry a valuable key to many a secret of other times.

To the genealogist a knowledge of Heraldry is indispensable. Coats of arms in church windows, on the walls, upon tombs, and especially on seals, are documents of great value. Many persons of the same name can now only be classed with their proper families by an inspection of the arms they bore. In Wales, where the number of surnames is very limited, families are much better recognized by their arms than by their names.[5]

The painter, in representing the gaudy scenes of the courts and camps of other days, can by no means dispense with a knowledge of our science; and the architect[Pg ix] who should attempt to raise some stately Gothic fane, omitting the well-carved shield, the heraldric corbel, and the blazoned grandeur of

“rich windows that exclude the light,”

would inevitably fail to impart to his work one of the greatest charms possessed by that noblest of all styles of building, and produce a meagre, soulless, abortion! Heraldry is, then, in the eyes of every man of any pretensions to taste, a useful, because an indispensable, science.

Now for an argument far stronger than all: Heraldry has been known to further the ends of justice. “I know three families,” says Garter Bigland, “who have acquired estates by virtue of preserving the arms and escutcheons of their ancestors.” I repeat, therefore, without the fear of contradiction, that Heraldry is a useful science. Q. E. D.

With respect to the sheets now submitted to the reader a few observations may be necessary. In the first place, I wish it to be understood that I have avoided, as much as possible, the technicalities of blazon: it was not my wish to supersede (even had I been competent to do so) the various excellent treatises on the subject already extant. The sole motive I entertained in writing this volume was a desire to render the science of Heraldry more intelligible to the general reader, and to present it in aspects more interesting and attractive than those writers can possibly[Pg x] do who treat of blazon merely as an art, and to make him acquainted with its origin and progress by means of brief historical and biographical sketches, and by inquiries into the derivation and meaning of armorial figures. In such an antient and well-explored field there has been but little scope for original discovery; but if I have succeeded in concentrating, and placing in a somewhat new light, old and well-known truths, my labour has not been lost, and my wish to render popular a too-much neglected study has been in some measure realized.

The references at the foot of nearly every page render acknowledgments to the authors whose works I have consulted almost unnecessary. It is, however, but justice to confess my obligations to Dallaway and Montagu for the general subject, to Noble for the notices of the heralds, and to Moule for the bibliography. For the illustrations and extracts I am principally indebted to the Boke of St. Albans, Leigh, Bossewell, Ferne, Guillim, Morgan, Randle Holme, and nearly all the writers of the antient school; whose works are rarely met with in an ordinary course of reading. From all these, both antient and modern, it has been my aim to select such points as appeared likely to interest both those who have some acquaintance with the subject and those who are confessedly ignorant of it.

Besides the authors of acknowledged reputation named above, I have consulted many others of comparatively little importance and value, convinced with[Pg xi] Pliny, “nullum esse librum tam malum ut non aliquâ parte posset prodesse.” Should a small proportion only of the reading public peruse my ‘Curiosities of Heraldry’ on the same principle, I shall not want readers!

My thanks are due to William Courthope, Esq. Rouge-Croix pursuivant of arms, for several obliging communications from the records of the Heralds’ Office, as well as for the great courtesy and promptitude with which he has invariably attended to every request I have had occasion to make during the progress of the work.

For the notice of the interesting relic discovered at Lewes (Appendix E), I am indebted to the kindness of W. H. Blaauw, Esq., M.A., author of the ‘Barons’ War,’ some remarks from whom on the subject were read at the late meeting of the Archæological Association at Canterbury, where the relic itself was exhibited.

The reader is requested to view the simple designs which illustrate these pages with all the candour with which an amateur draughtsman is usually indulged. Every fault they exhibit belongs only to myself, not to Mr. Vasey, the engraver, who, unlike Sir John Ferne’s artist,[6] must be acknowledged to have “done his duety” in a very creditable manner.

[Pg xii]It is not unlikely that I may be called upon to justify the orthography of several words of frequent occurrence in this work. I will therefore anticipate criticism by a remark or two, premising that I am too thoroughly imbued with the spirit of antiquarianism to make innovations without good and sufficient reason. The words to which I allude are antient, lyon, escocheon, and, particularly, heraldric. The first three cannot be regarded as innovations, as they were in use centuries ago. For ‘antient,’ apology is scarcely necessary, as many standard writers have used it; and it must be admitted to be quite as much like the low Latin antianus as ancient is. ‘Lyon’ looks picturesque, and seems to be in better keeping with the form in which the monarch of the forest is pourtrayed in heraldry than the modern spelling: an antiquarian predilection is all that I can urge in its defence. I would never employ it except in heraldry. ‘Escocheon’ is used by many modern writers on heraldry in preference to escutcheon, not only as a more elegant orthography, but as a closer approximation to the French écusson, from which it is derived.

For ‘HERALDRIC’ more lengthened arguments may be deemed necessary, as I am not aware that it occurs in any English dictionary. This adjective is almost invariably spelt without the R—heraldic; and that orthography, though sometimes correct, is still oftener false. I contend that two spellings are necessary,[Pg xiii] because two totally different words are required in different senses,—to wit,

I. Heraldic, belonging to a herald; and

II. Heraldric, belonging to heraldry.

I will illustrate the distinction by an example or two.

(I) “The office of Garter is the ‘ne plus ultra’ of heraldic ambition,” i. e., it is the height of the herald’s ambition ultimately to arrive at that honour. The word here has no relation whatever to proficiency in the science of coat-armour or heraldry, since it is possible that a herald or pursuivant may entertain the desire of gaining the post, causâ honoris, without any particular predilection for the study. Again,

“Queen Elizabeth was a staunch defender of heraldic prerogatives;” in other words, she defended the rights and privileges of her officers of arms; not the prerogatives of coats of arms, for to what prerogatives can painted ensigns lay claim?

(II) “A. B. is engaged in heraldric pursuits;” that is, in the study of armorial bearings; not in the pursuits of a herald, which consist in the proclamation of peace or war, the attendance on state ceremonials, the granting of arms, &c. To say that A. B., who has no official connexion with the College of Arms, is a herald, would be an obvious misnomer, although he may be quite equal in heraldrical skill to any gentleman of the tabard.

“The so-called arms of the town of Guildford have[Pg xiv] nothing heraldric about them,” that is, they are not framed in accordance with the laws of blazon. To say that they are not heraldic, would be to say that they do not declare war, attend coronations, wear a tabard, or perform any of the functions of a herald—a gross absurdity.

A literary friend, who objects to my reasoning, thinks that the one word, heraldic, answers every purpose for both applications. That it has done so, heretofore, is not certainly a reason why it should after the distinction has been pointed out. Besides, my doctrine is not unsupported by analogy. We have a case precisely parallel in the words monarchal and monarchical; and he who would charge me with innovation must, to be consistent with himself, expunge monarchical from his dictionary as a useless word.

Lewes; Dec. 1844.

Contents.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | THE FABULOUS HISTORY OF HERALDRY | 1 |

| II | THE AUTHENTIC HISTORY OF HERALDRY | 15 |

| III | RATIONALE OF THE FIGURES EMPLOYED IN HERALDRY | 49 |

| IV | THE CHIMERICAL FIGURES OF HERALDRY | 89 |

| V | THE LANGUAGE OF ARMS | 105 |

| VI | ALLUSIVE ARMS—ARMES PARLANTES | 119 |

| VII | CRESTS, SUPPORTERS, BADGES, etc. | 133 |

| VIII | HERALDRIC MOTTOES | 151 |

| IX | HISTORICAL ARMS—AUGMENTATIONS | 161 |

| X | DISTINCTIONS OF RANK AND HONOUR | 197 |

| XI | HISTORICAL NOTICES OF THE COLLEGE OF ARMS | 219 |

| XII | BRIEF NOTICES OF DISTINGUISHED HERALDS AND HERALDRIC WRITERS, WITH QUOTATIONS FROM THEIR WORKS |

245 |

| XIII | GENEALOGY | 281 |

| [Pg xvi] | Appendix. | |

| A | ON DIFFERENCES IN ARMS, NOW FIRST PRINTED FROM A MS. BY SIR EDWARD DERING, BART. |

297 |

| B | THE ANTIENT PRACTICE OF BORROWING ARMORIAL ENSIGNS ILLUSTRATED FROM THE ARMS OF CORNISH FAMILIES |

309 |

| C | ABATEMENTS | 313 |

| D | GRANT OF ARMS TEMP. EDW. III. | 315 |

| E | NOTICE OF AN ANTIENT STEELYARD WEIGHT DISCOVERED AT LEWES |

317 |

Errata.

| Page 15, | line 6, for pays? read pays! |

| 20, | — 15, for preterea read præterea. |

The distinction between the supports and tenans of French heraldry made at page 144 is erroneous. The true distinction is that human figures and angels, when employed to support the shield, are called tenans, while quadrupeds, fishes, or birds engaged in the same duty are styled supports.

THE

CURIOSITIES OF HERALDRY.

Fabulous History of Heraldry.

“You had a maister that hath fetched the beginning of Gentry from Adam, and of Knighthood from Olybion.”

Ferne’s Blazon of Gentrie.

“Gardons nous de mêler le douteux an certain, et le chimérique avec le vrai.”

Voltaire, Essai sur les Mœurs.

ntiquity has, in a greater or less degree, charms for all; and it is

supposed to stamp such a value on things as nothing else can confer. This

feeling, unexceptionable in itself, is liable to great abuse; especially

in relation to historical matters. In States and in Families, Antiquity

implies greatness,[Pg 2] strength, and those other attributes which command

veneration and respect. Hence the first historians of nations have

uniformly endeavoured to carry up their annals to periods far beyond the

limits of probability, thus rendering the earlier portions of their works

a tissue of absurdity deduced from the misty regions of tradition,

conjecture, and song.[7]

ntiquity has, in a greater or less degree, charms for all; and it is

supposed to stamp such a value on things as nothing else can confer. This

feeling, unexceptionable in itself, is liable to great abuse; especially

in relation to historical matters. In States and in Families, Antiquity

implies greatness,[Pg 2] strength, and those other attributes which command

veneration and respect. Hence the first historians of nations have

uniformly endeavoured to carry up their annals to periods far beyond the

limits of probability, thus rendering the earlier portions of their works

a tissue of absurdity deduced from the misty regions of tradition,

conjecture, and song.[7]

This reverence for antiquity has extended itself to genealogists, and to those who have recorded the history of sciences and inventions. Thus has it been with the earliest writers on Heraldry, a system totally unknown till within the last thousand years; but which in the fancies of its zealous admirers has been presumed to have existed, not merely in the first ages of the world, but at a period

“Ere Nature was, or Adam’s dust

Was fashioned to a man!”

We are gravely assured by a writer of the fifteenth century that heraldric ensigns were primarily borne by the ‘hierarchy of the skies,’ “At hevyn,” says the author of the Boke of St. Albans, “I will begin; where were V orderis of aungelis, and now stand but IV, in cote armoris of knawlege, encrowned ful hye with precious stones, where Lucifer with mylionys of aungelis, owt of hevyn fell into hell and odyr[Pg 3] places, and ben holdyn ther in bondage; and all [the remaining angels] were erected in hevyn of gentill nature!”

Thus, in one short sentence, the origin both of nobility and of its external symbols is summarily disposed of. When proofs are not to be adduced, how can we regret that it is no longer?

But to descend a little lower, let us quote again the poetical language of this indisputable authority: “Adam, the begynnyng of mankind, was as a stocke unsprayed and unfloreshed,”—having neither boughs nor leaves—“and in the braunches is knowledge wich is rotun and wich is grene;” that is, if I rightly understand it, (for poetry is not always quite intelligible,) both the gentle and the ungentle, the earl and the churl, are descended from one progenitor; omnes communem parentem habent; a truth which, it is presumed, will not be called in question.

The gentility of the great ancestor of our race is stoutly contended for, and, that his claim to that distinction might not want support, Morgan, an enthusiastic armorist of the seventeenth century, has assigned him two coats of arms; one as borne in Eden—when he neither used nor needed either coat for covering or arms for defence—and another suited to his condition after the fall. The first was a plain red shield, described in the language of modern heraldry as ‘gules,’ while the arms of Eve, a shield of white, or ‘argent,’ were borne upon it as an ‘escocheon of pretence,’ she being an heiress! The arms of Abel were, as a matter of course, those of his father and mother borne ‘quarterly,’ and ensigned with a crosier, like that of a bishop, to show that he was a ‘shepheard’[8]

Sir John Ferne, a man of real erudition, was so far carried away by extravagant notions of the great antiquity of heraldric[Pg 4] insignia, as seriously to deduce the use of furs in heraldry from the ‘coats of skins’ which the Creator made for Adam and Eve after their transgression. This, independently of its absurdity, is an unfortunate idea; for coats of arms are as certainly marks of honour as these were badges of disgrace; and as Morgan says, ‘innocens was Adam’s best gentility.’[9] The second coat of Adam, says this writer, was ‘paly tranche, divided every way and tinctured of every colour.’ Cain, also, after his fall, changed his armorials “by ingrailing and indented lines—to show, as the preacher saith, There is a generation whose teeth are as swords, and their jaw-teeth as knives to devour the poor from the earth.” He was the first, it is added, who desired to have his arms changed—‘So God set a mark upon him!’[10]

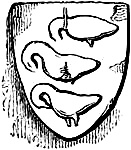

This ante-diluvian heraldry is expatiated upon by our author in a manner far too prolix for us to follow him through all his grave statements and learned proofs. I shall therefore only observe, en passant, that arms are assigned to the following personages, viz.: Jabal, the inventor of tents, Vert, a tent argent, (a white tent in a green field!) Jubal, the primeval musician, Azure, a harp, or, on a chief argent three rests gules;[11] Tubal-Cain, Sable, a hammer argent, crowned or,[Pg 5] and Naamah, his sister, the inventress of weaving, In a lozenge gules, a carding-comb argent.

Noah, according to the Boke of St. Albans, “came a gentilman by kynde ... and had iij sonnys begetyn by kinde ... yet in theys iij sonnys gentilness and ungentilnes was fownde.” The sin of Ham degraded him to the condition of a churl; and upon the partition of the world between the three brethren Noah pronounced a malediction against him. “Wycked kaytiff,” says he, “I give to thee the north parte of the worlde to draw thyne habitacion, for ther schall it be, where sorow and care, cold and myschef, as a churle thou shalt live in the thirde parte of the worlde wich shall be calde Europe, that is to say, the contre of churlys!”

“Japeth,” he continues, “cum heder my sonne, thou shalt have my blessing dere.... I make the a gentilman of the west parte of the world and of Asia, that is to say, the contre of gentilmen.” He then in like manner creates Sem a gentleman, and gives him Africa, or “the contre of tempurnes.”[12]

“Of the offspryng of the gentleman Japheth come Habraham, Moyses, Aron, and the profettys, and also the kyng of the right lyne of Mary, of whom that gentilman Jhesus ... kyng of the londe of Jude and of Jues, gentilman by his modre Mary prynce[ss] of cote-armure!”... “Jafet made the first target and therin he made a ball in token of all the worlde.”

Morgan’s researches do not seem to have furnished him with the arms of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, but those of the twelve patriarchs are given by him and others. Joseph’s[Pg 6] “coat of many colours,” Morgan, by a strange oversight, makes to consist of two tinctures only, viz. black, chequered with white—in the language of heraldry, chequy sable and argent,—to denote the lights and shadows of his history.

The pathetic predictions and benedictions pronounced by the dying patriarch Jacob to his sons, furnished our old writers with one of their best pretences for giving coat-armour to persons in those remote ages. The standards ordered to be set up around the Israelitish camp in the desert[13] are likewise adduced in support of the notion that regular heraldry was then known. The arms of the twelve tribes are given by Morgan in the following hobbling verses:[14]

“Judah bare Gules, a lion[15] couchant or;

Zebulon’s black Ship’s[16] like to a man of war;

Issachar’s asse[17] between two burthens girt;

As Dan’s[18] sly snake lies in a field of vert;

Asher with Azure a Cup[19] of gold sustains;

And Nephtali’s Hind[20] trips o’er the flow’ry plains;

Ephraim’s strong Ox lyes with the couchant Hart;

Manasseh’s Tree its branches doth impart;

Benjamin’s Wolfe in the field gules resides;

Reuben’s field argent and blew bars wav’d glides;

Simeon doth beare his Sword; and in that manner

Gad, having pitched his Tent, sets up his Banner.”

The same authority gives as the arms of Moses a cross, because he preferred “taking up the cross,” and suffering[Pg 7] the lot of his brethren to a life of pleasure and dignity in the court of Pharaoh. The ‘parfight armory of Duke Joshua,’ given by Leigh, is Partie bendy sinister, or and gules, a backe displayed sable. The arms of Gideon were Sable, a fleece argent, a chief azure gutté d’eau,[21] evidently a ‘composition’ from the miracle recorded in the Book of Judges. To Samson is ascribed, Gules, a lion couchant or, within an orle argent, semée of bees sable, an equally evident allusion to a passage in the bearer’s history. David, as a matter of course, bore a golden harp in a field azure.[22]

But it is not alone to the worthies of sacred history that these honourable insignia are ascribed—the heroes of classical story, too, had their ‘atchievements,’ Hector of Troy, for example, bore, Sable, ij lyons combatand or.[23] Here again our great authority, Dame Julyan Berners,[24] may be cited. “Two thousand yere and xxiiij,” says she, “before thyncarnation of Christe, Cote-Armure was made and figurid at the sege of Troye, where in gestis troianorum it tellith that the first begynnyng of the lawe of armys was; the which was effygured and begunne before any lawe in the world bot the lawe of nature, and before the X commaundementis of God.”

I have been favoured with the following curious extract[Pg 8] from a MS. at the College of Arms,[25] which also refers the origin of arms to the siege of Troy. I believe it has never been printed.

“What Armes be, and where they were firste invented. As kinges of Armes record, the begynynge of armes was fyrste founded at the great sege of Troye wthin the Cytie and wthout, for the doughtines of deades don on bothe partyes and for so mouche as thier were soo many valliaunt knights on bothe sydes wch did soo great acts of Armes, and none of them myght be knowen from other, the great Lords on both p’ties by thier dyscreate advice assembled together and accorded that every man that did a great acte of armes shoulde bere upon him a marke in token of his doutye deades, that the pepoell myght have the betr knowledge of him, and if it were soo that suche a man had any chylderen, it was ordeyned that they should also bere the same marke that their father did wth dyvers differences, that ys to saye, Theldeste as his father did wth a labell, the secounde wth a cressente, the third wth a molett, the fourth a marlet, the vth an annellet, the vjth a flewer delisse. And if there be anye more than sixe the rest to bere suche differences as lyketh the herauld to geve them. And when the said seige was ended ye lordes went fourth into dyvers landes to seke there adventures, and into England came Brute and [his] knights wth there markes and inhabited the land; and after, because the name of MERKES was rewde, they terned the same into ARMES, for as mouche as that name was far fayerer, and becausse that markes were gotten through myght of armes of men.”

The humour of Alexander the Great must have been [Pg 9]somewhat of the quaintest when he assumed the arms ascribed to him by Master Gerard Leigh, to wit, Gules a GOLDEN LYON SITTING IN A CHAYER and holding a battayle-axe of silver.[26] The ‘atchievement’ of Cæsar was, if we may trust the same learned armorist, Or, an eagle displayed with two heads sable.[27]

[Pg 10]Arms are also assigned to King Arthur, Charlemagne, Sir Guy of Warwick, and other heroes, who, though belonging to much more recent periods, still flourished long before the existence of the heraldric system, and never dreamed of such honours.

That these pretended armorials were the mere figments of the writers who record them, no one doubts. In these ingenious falsehoods we recognize a principle similar to that which produced the ‘pious frauds’ of enthusiastic churchmen, and to that which led self-duped alchemists to deceive others. In their zeal for the antiquity of arms—a zeal of so glowing a character that no one who has not read their works can estimate it—they imagined that they must have existed from the beginning of the world. Then, throwing the reins upon the neck of their fancy, they ascribed to almost every celebrated personage of the earliest ages, the ensigns they deemed the most appropriate to his character and pursuits. The feeling inducing such a procedure originated in a mistake as to the antiquity of chivalry, of which heraldry was part and parcel. Feelings unknown before the existence of this institution are attributed to the heroes of antiquity. ‘Duke Joshua’ is presumed to have been only another Duke William of Normandy, influenced in war by similar motives and surrounded by the same social circumstances in time of peace. Chaucer talks of classical heroes as if they were knights of some modern order; and Lydgate, in his Troy Boke invests the heroes of the Iliad with the costume of his own times, carrying emblazoned shields and fighting under feudal banners:

[Pg 11]

“And to behold in the knights shields

The fell beastes.

“Where that he saw,

In the shields hanging on the hookes,

The beasts rage.

“The which beastes as the storie leres

Were wrought and bete upon their banners

Displaied brode, when they schould fight.”[28]

The fabulous history of the science might be fairly deduced to the eleventh century, as the Saxon monarchs up to that date are all represented to have borne arms. Yet as there are not wanting, even in our day, those who admit the authenticity of those bearings, their claims will be briefly referred to in the next chapter.

In justice to the credulous and inventive armorists of the ‘olden tyme,’ the reader should be reminded that warriors did, in very antient times, bear various figures upon their shields. These seem in general to have been engraved in, rather than painted upon, the metal of which the shield was composed. The French word escu and escussion, the Italian scudo, and the English escocheon, are evident derivations from the Latin scutum, and the equivalent word clypeus is derived from the Greek verb γλυφειν, TO ENGRAVE. But those sculptured devices were regarded as the peculiar ensigns of one individual, who could change them at pleasure, and did not descend hereditarily like the modern coat of arms.

A few references to the shields here alluded to may not be unacceptable. Homer describes the shield of Agamemnon[Pg 12] as being ornamented with the Gorgon, his peculiar badge; and Virgil says of Aventinus,[29] the son of Hercules—

“Post hos insignem palmâ per gramina currum,

Victoresque ostentat equos, satus Hercule pulchro

Pulcher Aventinus: clypeoque, insigne paternum,

Centum angues, cinctamq: gerit serpentibus hydram.”

Æneid. vii, 655.

“Next Aventinus drives his chariot round

The Latian plains, with palms and laurels crowned;

Proud of his steeds he smokes along the field,

His father’s hydra fills his ample shield.”

Dryden, vii, 908.

The Greek dramatists describe the symbols and war-cries placed upon their shields by the seven chiefs, in their expedition against the city of Thebes. As an example, Capaneus is represented as bearing the figure of a giant with a blazing torch, and the motto, “I will fire the city!” Such ensigns seem to have been the peculiar property of the valiant and well-born, and so far they certainly resembled modern heraldry. Virgil, speaking of Helenus, whose mother had been a slave, says,

“Slight were his arms—a sword and silver shield;

No marks of honour charged its empty field.”[30]

Several of our more recent writers, while they disclaim all belief of the existence of armorial bearings in earlier times,[Pg 13] still think they find traces of these distinctions in the days of the Roman commonwealth. The family of the Corvini are particularly cited as having hereditarily borne a raven as their crest; but this device was, as Nisbet has shown,[31] merely an ornament bearing allusion to the apocryphal story of an early ancestor of that race having been assisted in combat by a bird of this species. The jus imaginum of the Romans is also adduced. In every condition of civilized society distinctions of rank and honour are recognized. Thus the Romans had their three classes distinguished as nobiles, novi, and ignobiles. Those whose ancestors had held high offices in the state, as Censor, Prætor, or Consul, were accounted nobiles, and were entitled to have statues of their progenitors executed in wood, metal, stone, or wax, and adorned with the insignia of their several offices, and the trophies they had earned in war. These they usually kept in presses or cabinets, and on occasions of ceremony and solemnity exhibited before the entrances of their houses. He who had a right to exhibit his own effigy only, was styled novus, and occupied the same position with regard to the many-imaged line as the upstart of our own times, who bedecks his newly-started equipage with an equally new coat of arms, does to the head of an antient house with a shield of forty quarterings. The ignobiles were not permitted to use any image, and therefore stood upon an equality with modern plebeians, who bear no arms but the two assigned them by the heraldry of nature.

The patricians of our day to a certain extent carry out the jus imaginum of antiquity, only substituting painted canvas for sculptured marble or modelled wax; and there is no sight[Pg 14] better calculated to inspire respect for dignity of station than the gallery of some antient hall hung with a long series of family portraits; in which, as in a kind of physiognomical pedigree, the speculative mind may also find matter of agreeable contemplation. The jus imaginum doubtless originated in the same class of feelings that gave birth to heraldry, but there is no further connexion or analogy between the two. It is to hereditary shields and hereditary banners we must limit the true meaning of heraldry, and all attempts to find these in the classical era will end in a disappointment as inevitable as that which accompanies the endeavour to gather “grapes of thorns or figs of thistles.”

Authentic History of Heraldry.

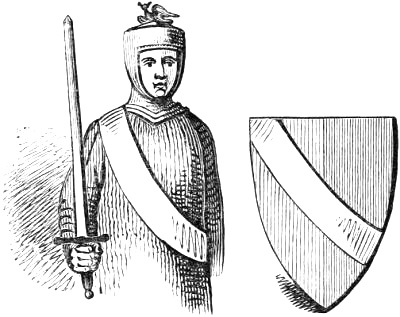

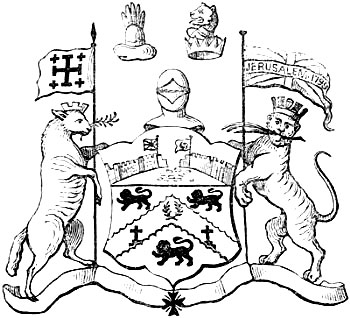

(John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, temp. Hen. VI,

in his surcoat or coat of arms.)[32]

“Vetera quæ nunc sunt fuerunt olim nova.”

“L’histoire du blazon! mais c’est l’histoire tout entière de notre pays!”

Jouffroy d’Eschavannes.

Having given some illustrations of the desire of referring the heraldric system to times of the most remote antiquity, and shown something of the misapplication of learning to prove what was incapable of proof, let us now leave the obscure byways of those mystifiers of truth and fabricators of error, and emerge into the more beaten path presented to us in what may be called the historical period, which is confined within the last eight centuries. The history of the sciences,[Pg 16] like that of nations, generally has its fabulous as well as its historical periods, and this is eminently the case with heraldry; yet in neither instance is there any exact line of demarcation by which the former are separable from the latter. This renders it the duty of a discriminating historian to act with the utmost caution, lest, on the one hand, truths of a remote date should be sacrificed because surrounded by the circumstances of fiction, and lest, on the other, error should be too readily admitted as fact, because it comes to us in a less questionable shape; and I trust I shall not be deemed guilty of misappropriation if I apply to investigations like the present, that counsel which primarily refers to things of much greater import, namely, “Prove all things; hold fast that which is good.”

The germ of that flourishing tree which eventually ramified into all the kingdoms of Christendom, and became one of the most striking and picturesque features of the feudal ages, and the most gorgeous ornament of chivalry, and which interweaves its branches into the entire framework of mediæval history, is doubtless to be found in the banners and ornamented shields of the warriors of antiquity. Standards, as the necessary distinctions of contending parties on the battle-field, must be nearly or quite as antient as war itself; and every such mark of distinction would readily become a national cognizance both in war and peace.[33] But it was reserved for later ages to apply similar marks and symbols to the purpose of distinguishing different commanders on the same side, and even after this became general it was some[Pg 17] time ere the hereditary transmission of such ensigns was resorted to as a means of distinguishing families, which in the lapse of ages—the warlike idea in which they had their origin having vanished—has become almost the only purpose to which they are now applied.

The standards used by the German princes in the centuries immediately preceding the Norman Conquest, are conjectured to have given rise to Heraldry, properly so called. Henry l’Oiseleur (the Fowler), who was raised to the throne of the West in 920, advanced it to its next stage when, in regulating the tournaments—which from mismanagement had too often become scenes of blood—he ordered that all combatants should be distinguished by a kind of mantles or livery composed of lists or narrow pieces of stuff of opposite colours, whence originated the pale, bend, &c.—the marks now denominated ‘honourable ordinaries.’[34]

If the honour of inventing heraldry be ascribed to the Germans, that of reducing it to a system must be assigned to France. To the French belong “the arrangement and combination of tinctures and metals, the variety of figures effected by the geometrical positions of lines, the attitudes of animals, and the grotesque delineation of monsters.”[35] The art of describing an heraldric bearing in proper terms is called blasonry, from the French verb blasonner, whence also we derive our word blaze in the sense of to proclaim or make known.

“The heavens themselves blaze forth the death of princes.” Shak.

“But he went out and began to publish it much, and to blaze abroad the matter.” St. Mark.

“’Tis still our greatest pride,

To blaze those virtues which the good would hide.” Pope.

[Pg 18]The verb seems to have come originally from the German blasen, to blow a horn. At the antient tournaments the attendant heralds proclaimed with sound of trumpet the dignity of the combatants, and the armorial distinctions assumed by them; and hence the application of the word to the scientific description of coat armour.[36] The arrangement of the tinctures and charges of heraldry into a system may be regarded as the third stage in the history of the science. This, as we have just seen, was achieved by the French: and hence the large admixture of old French terms with words of native growth in our heraldric nomenclature.

Speed and other historians give the arms of a long line of the Anglo-Saxon and Danish monarchs of England up to the period of the Norman Conquest; but we search in vain for contemporary evidence that armorial distinctions were then known. The MSS. of those early times which have descended to us are rich in illustrations of costume, but no representation of these ‘ensigns of honour’ occurs in any one of them. It seems probable that Speed was misled by the early chroniclers, who in their illuminated tomes often represented events of a much earlier date in the costume of their own times. Thus, in a work by Matthew Paris, who flourished in the thirteenth century, Offa, a Danish king of the tenth, is represented in the habits worn at the first-mentioned date, and bearing an armorial shield according to the then existing fashion.

At what period the colours and charges of the banner began to be copied upon the shield is uncertain. A proof that regular heraldry was unknown at the era of the [Pg 19]Conquest, is furnished by that valuable monument, the Bayeux Tapestry, a pictorial representation of the event, ascribed to the wife of the Conqueror. In these embroidered scenes neither the banner nor the shield is furnished with proper arms. Some of the shields bear the rude effigies of a dragon, griffin, serpent or lion, others crosses, rings, and various fantastic devices;[37] but these, in the opinion of the most learned antiquaries, are mere ornaments, or, at best, symbols, more akin to those of classical antiquity than to modern heraldry. Nothing but disappointment awaits the curious armorist, who seeks in this venerable memorial the pale, the bend, and other early elements of arms. As these would have been much more easily imitated with the needle than the grotesque figures before alluded to, we may safely conclude that personal arms had not yet been introduced.[38]

Dallaway asserts that, after the Conquest, William “encouraged,[Pg 20] but under great restrictions, the individual bearing of arms;” but, strangely, does not cite the most slender authority for the assertion. Camden and Spelman agree that arms were not introduced until towards the close of the eleventh century, which must have been within a very short time of the Conqueror’s death. Others again, with more probability, speak of the second Crusade (A.D. 1147) as the date of their introduction into this country. But even at this period the proofs of family bearings are very scanty. Traditions, indeed, are preserved in many families, of arms having been acquired during this campaign, and in a future chapter several examples will be quoted, rather as a matter of curiosity than as historical proof; for all tradition, and especially that which tends to flatter a family by ascribing to it an exaggerated antiquity, will generally be found to be vox et preterea nihil. The arms said to occur on seals in the seventh and eighth centuries may be dismissed as merely fanciful devices, having no connexion whatever with the heraldry of the twelfth and thirteenth.

Towards the close of the twelfth century, and at the beginning of the thirteenth, A.D. 1189-1230, it was usual for warriors to carry a miniature escocheon suspended from a belt, and decorated with the arms of the wearer.[39]

(Rich. I. from his second Great Seal.)

It was in the time of Richard I that heraldry assumed more of the fixed character it now bears. That monarch appears on his great seal of the date of 1189, with a shield containing two lions combatant; but in his second great seal (1195) three lions passant occur, as they have ever since been used by his successors. Before coming to the throne, as Earl of Poitou, he had borne lions in some attitude; for,[Pg 21] in an antient poem, cited by Dallaway, William de Barr, a French knight, utters an exclamation to this effect: “Behold the Count of Poitou challenges us to the field; see he calls us to the combat; I know the grinning lions in his shield;” and in the romance of ‘Cuer de Lyon,’ we read the following couplet:

“Upon his shoulders a Schelde of stele,

With the ‘lybbardes’[40] painted wele.”

[Pg 22]The earliest representation of arms upon a seal is of the date of 1187.[41] The embellishment of seals was one of the first as well as one of the most interesting and useful applications of Heraldry. Seals, at first rude and devoid of ornament, became, in course of time, beautiful pieces of workmanship, elaborately decorated with arms, equestrian figures, and tabernacle work of gothic architecture.

The Crusades are admitted by all modern writers to have given shape to heraldry. And although we cannot give credit to many of the traditions relating to the acquisition of armorial bearings by valorous knights on the plains of Palestine, yet there is no doubt that many of our commonest charges, such as the crescent, the escallop-shell, the water-bowget, &c., are derived from those chivalric scenes. Salverte observes that “the ensigns which adorned the banner of a knight had not, in earlier times, been adopted by his son, jealous of honouring, in its turn, the emblem which he himself had chosen. But this glorious portion of the heritage of a father or a brother who had died fighting for the cross was seized with avidity by his successor on the fields of Palestine; for, in changing the paternal banner, he would have feared that he should not be recognized by his own vassals and his rivals in glory. History expressly tells us that, at this epoch, many of the chiefs of the crusaders rendered the symbols which they bore peculiar to their own house.”[42] Dallaway, with his accustomed elegance, remarks, “Those chiefs who, during the holy war, returned to their own country, were industrious to call forth the highest admiration of their martial exploits in the middle ranks. Ambitious of displaying[Pg 23] the banners they had borne in the sacred field, they procured every external embellishment that could render them either more beautiful as to the execution of the armorial designs, or more venerable as objects of such perilous attainment. The bannerols of this era were usually of silk stuffs, upon which was embroidered the device; and the shields of metal, enamelled in colours, and diapered or diversified with flourishes of gold and silver. Both the arts of encaustic painting and embroidery were then well known and practised, yet of so great cost as to be procured only by the most noble and wealthy. Amongst other pageantries was the dedication of these trophies to some propitiatory Saint, over whose shrine they were suspended, and which introduced armorial bearings in the decoration of churches, frequently carved in stone, painted in fresco upon the walls, or stained in glass in the windows. The avarice of the ecclesiastics in thus adding to their treasures conduced almost as much as the military genius of the age to the more general introduction of arms. So sanctioned, the use of them became indispensable.”[43]

[Pg 24]By the time of Edward the First we find that all great commanders had adopted arms, which were at that date really coats; the tinctures and charges of the banner and shield being applied to the surcoat, or mantle, which was worn over the armour, while the trappings of horses were decorated in a similar manner.

In the ages immediately subsequent to the Crusades, heraldric ensigns began to be generally applied as architectural decorations. The shields upon which they were first represented were in the form of an isosceles triangle, slightly curved on its two equal sides; but soon afterwards they began to assume that of the gothic arch reversed, a shape probably adopted with a view to such decoration, as harmonising better with the great characteristics of the pointed style. Painted glass, too, in its earliest application, was employed to represent military portraits, and arms with scrolls containing short sentences, from which family mottoes may have originated. Warton[44] places this gorgeous ornament at an era earlier than the reign of Edward II.

Encaustic tiles, also, which were introduced in the early days of heraldry, afforded another means of displaying the insignia of warriors. They are still found in the pavements of many of our cathedrals and old parish churches.

[Pg 25]Rolls of Arms, which afford, after seals, the best possible evidence of the ancient tinctures and charges, occur so early as the time of Henry III. A document of this description, belonging to that reign, is preserved in the College of Arms, and contains upwards of 200 coats emblazoned or described in terms of heraldry differing very little from the modern nomenclature. In a subsequent chapter I shall have occasion to refer for some facts to this curious and valuable manuscript.

In the succeeding reigns the science rapidly increased in importance and utility. The king and his chief nobility began to have heralds attached to their establishments. These officials, at a later date, took their names from some badge or cognizance of the family whom they served, such as Falcon, Rouge Dragon, or from their master’s title, as Hereford, Huntingdon, &c. They were, in many instances, old servants or retainers, who had borne the brunt of war,[45] and who, in their official capacity, attending tournaments and battle-fields, had great opportunities of making collections of arms, and gathering genealogical particulars. It is to them, as men devoid of general literature and historical knowledge, Mr. Montagu ascribes the fabulous and romantic stories connected with antient heraldry; and certainly they had great temptations to falsify facts, and give scope to invention when a championship for the dignity and antiquity of the families upon whom they attended was at once a labour of love and an essential duty of their office.

The Roll of Karlaverok, the name of which must be familiar to every reader who has paid any attention to heraldry,[Pg 26] is a poem in Norman-French, describing the valorous deeds of Edward I and his knights at the siege of the castle of Karlaverok, in Dumfriesshire, in the year 1300. This roll, which is curious on historical grounds, and by no means contemptible as a poem, possesses especial charms for the heraldric student. It describes with remarkable accuracy the banners of the barons and knights who served in the expedition against Scotland, and “affords evidence of the perfect state of the science of heraldry at that early period.” It is believed to have been written by Walter of Exeter, a Franciscan friar, further known as the author of the romantic history of Guy, Earl of Warwick. A contemporary copy of this valuable relic exists in the British Museum, and another copy, transcribed from the original, is in the Library of the College of Arms. The latter was published in 1828 by Sir Harris Nicolas, with a translation and memoirs of the personages commemorated by the poet.

The poem commences by stating that, in the year of Grace one thousand three hundred, the king held a great court at Carlisle, and commanded his men to prepare to go together with him against his enemies the Scots. On the appointed day the whole host was ready. “There were,” says the chivalrous friar, “many rich caparisons embroidered on silks and satins; many a beautiful penon fixed to a lance, and many a banner displayed.

“And afar off was the noise heard of the neighing of horses; mountains and valleys were everywhere covered with sumpter horses and waggons with provisions, and sacks of tents and pavilions.

“And the days were long and fine [it was Midsummer]. They proceeded by easy journeys arranged in four squadrons; the which I will so describe to you that not one shall be[Pg 27] passed over. But first I will tell you of the names and arms of the companions, especially of the banners, if you will listen how.”

In truth, by far the greater portion of the composition consists of descriptions of the heraldric insignia borne upon the banners of the commanders, upwards of one hundred in number. The following are quoted as examples:

| “Henri le bon Conte de Nichole De prowesse enbrasse & a cole E en son coer le a souveraine Menans le eschiele primeraine Baniere ot de un cendall saffrin O un lion rampant porprin.” |

|

‘Henry the good Earl of Lincoln, burning with valour, which is the chief feeling of his heart, leading the first squadron, had a banner of yellow silk with a purple lion rampant.’[46]

| “Prowesse ke avoit fait ami De Guilleme de Latimier Ke la crois patee de or mier Portoit en rouge bien portraite Sa baniere ot cele parte traite.” |

|

‘Prowess had made a friend of William le Latimer, who[Pg 28] bore on this occasion a well-proportioned banner, with a gold cross patée, pourtrayed on red.’[47]

“Johans de Beauchamp proprement

Portoit le baniere de vair

Au douz tens et au sovest aier.”

‘John de Beauchamp

Handsomely bore his banner of vair,

To the gentle weather and south-west air.’[48]

The best authorities are agreed that coat-armour did not become hereditary until the reign of Henry III and his successor. Before that period families “kept no constant coat, but gave now this, anon that, sometimes their paternal, sometimes their maternal or adopted coats, a variation causing much obfuscation in history.”[49] Many of the nobility who had heretofore borne ensigns consisting of the honorable ordinaries, the simplest figures of heraldry, now began to charge them with other figures. Some few families, however, never adopted what are called common charges, but retained the oldest and simplest forms of bearing, such as bends, cheverons, fesses, barry, paly, chequy, &c.; and, as a general rule, such coats may be regarded as the most antient in existence. With respect to Welsh heraldry, Dallaway thinks that the families of that province did not adopt the symbols made use of by other nations, until its annexation to the English Crown by Edward I. Certain it is that many of the oldest families bear what may be termed[Pg 29] legendary pictures, having little or no analogy to the more systematic armory of England; such, for example, as a wolf issuing from a cave; a cradle under a tree with a child guarded by a goat, &c.

The reigns of Edward III and Richard II were the “palmy days” of heraldry. Then were the banners and escocheons of war refulgent with blazon; the light of every chancel and hall was stained with the tinctures of heraldry; the tiled pavement vied with the fretted roof; every corbel, every vane, spoke proudly of the achievements of the battle-field, and filled every breast with a lofty emulation of the deeds which earned such stately rewards. We, the men of this calculating and prosaic nineteenth century, have, it is probable, but a faint idea of the influence which heraldry exerted on the minds of our rude forefathers of that chivalrous age: but we can hardly refuse to admit that, by diffusing more widely the enthusiasm of martial prowess, it lent a powerful aid to the formation of our national character, and strongly tended to give to England that proud military ascendancy she has long enjoyed among the nations of the earth.[50]

(Ordeal Combat.)

At this period that peculiar species of ordeal, TRIAL BY COMBAT, the prototype of the modern duel, was licensed by the supreme magistrate. When a person was accused by another without any further evidence than the mere ipse dixit of the accuser, the defendant making good his own[Pg 30] cause by strongly denying the fact, the matter was referred to the decision of the sword,[51] and although the old proverb that “might overcomes right” was frequently verified in these encounters, the vanquished party was adjudged guilty of the crime alleged against him, and dealt with according to law. The charge usually preferred was that of treason, though the dispute generally originated in private pique between the parties. These combats brought together immense numbers of people. That between Sir John Annesley and Katrington, in the reign of Richard II, was fought before the palace at Westminster, and attracted more spectators than the king’s coronation had done.[52] All such encounters were regulated by laws which it was the province of the heralds to enforce.[53]

The TOURNAMENT, though proscribed by churchmen (jealous, as Dallaway observes, of shows in which they could play no part), had nothing in it of the objectionable character attaching to the judicial combat. Nor will it suffer, in the judgment of Gibbon, on a comparison with the Olympic games, “which, however recommended by the idea of classic[Pg 31] antiquity, must yield to a Gothic tournament, as being, in every point of view, to be preferred by impartial taste.”[54] Descriptions of tournaments occur in so many popular works that it is not here necessary to do more than to refer to them. The vivid picture of one by Sir Walter Scott in ‘Ivanhoe’ is probably fresh in the reader’s memory.

As early heraldry consisted of very simple elements, it cannot excite surprise that the same bearings were frequently adopted by different families unknown to each other; hence arose very violent disputes and controversies, as to whom the prior right belonged. The celebrated case of Scrope against Grosvenor in the reign of Richard II, may be cited as an example. The arms Azure, a bend or, were claimed by no less than three families, namely, Carminow of Cornwall, Lord Scrope, and Sir Robert Grosvenor. On the part of Scrope, it was asserted that these arms had been borne by his family from the Norman conquest. Carminow pleaded a higher antiquity, and declared they had been used by his ancestors ever since the days of king Arthur! The trial by combat had been resorted to by these two claimants without a satisfactory decision, wherefore it was decreed that both should continue to bear the coat as heretofore. The dispute between Scrope and Grosvenor was not so summarily disposed of; a trial, not by the sword, but by legal process, took place before the high Constables and the Earl Marshal, and lasted five years. The proceedings, which were printed in 1831 from the records in the Tower, occupy two large volumes! The depositions of many gentlemen bearing arms, touching this controversy, are given at full length, and present us with some curious and characteristic features of the times. Among many others[Pg 32] who gave evidence in support of the claims of Lord Scrope was the famous Chaucer. His deposition, taken from the above records, and printed in Sir Harris Nicolas’s elegant life of the poet, recently published, is interesting, no less from its connexion with the witness than for its curiosity in relation to our subject:

“Geoffrey Chaucer, Esquire, of the age of forty and upwards, armed for twenty-seven years, produced on behalf of Sir Richard Scrope, sworn and examined. Asked, whether the arms Azure, a bend or, belonged, or ought to belong, to the said Sir Richard? Said, Yes, for he saw him so armed in France, before the town of Retters,[55] and Sir Henry Scrope armed in the same arms with a white label, and with a banner; and the said Richard, armed in the entire arms, ‘Azure, with a bend or;’ and so he had seen him armed during the whole expedition, until the said Geoffrey was taken [prisoner.] Asked, how he knew that the said arms appertained to the said Sir Richard? Said, that he had heard say from Old Knights and Esquires, that they had been reputed to be their arms, as common fame and the public voice proved; and he also said that they had continued their possession of the said arms; and that all his time he had seen the said arms in banners, glass, paintings, and vestments, and commonly called the arms of Scrope. Asked, if he had heard any one say who was the first ancestor of the said Sir Richard, who first bore the said arms? Said, No, nor had he ever heard otherwise than that they were come of antient ancestry and old gentry, and used the said arms. Asked, if he had heard any one say how long a time the ancestors of the said Sir Richard had used the said arms? Said, No, but he had heard say that it passed the memory of man. Asked, whether he had ever heard of any interruption or challenge made by Sir Robert Grosvenor, or by his ancestors, or by any one in[Pg 33] his name, to the said Sir Richard, or to any of his ancestors? Said, No, but he said that he was once in Friday-street in London, and as he was walking in the street he saw hanging a new sign made of the said arms, and he asked what Inn that was that had hung out these arms of Scrope? and one answered him and said, No, Sir, they are not hung out for the arms of Scrope, nor painted there for those arms, but they are painted and put there by a knight of the county of Chester, whom men call Sir Robert Grosvenor; and that was the first time he ever heard speak of Sir Robert Grosvenor or of his ancestors, or of any other bearing the name of Grosvenor.”[56]

At this date the nobility claimed, and to a considerable extent exercised, the right of conferring arms upon their followers for faithful services in war. A memorable instance is related by Froissart, in which the Lord Audley, a famous general at the battle of Poictiers, rewarded four of his esquires in this manner. When the battle was over, Edward the Black Prince, calling for this nobleman, embraced him and said, “Sir James, both I myself and all others acknowledge you, in the business of the day, to have been the best doer in arms; wherefore, with intent to furnish you the better to pursue the wars, I retain you for ever my knight, with 500 marks yearly revenue, which I shall assign you out of my inheritance in England.” This was, at the period, a great estate, and the Lord Audley duly appreciated the generosity of the donation; yet, calling to mind his obligations in the conflict to his four squires, Delves, Mackworth, Hawkeston, and Foulthurst, he immediately divided the Prince’s gift among them, giving them, at the same time, permission to bear his own arms, altered in detail, for the[Pg 34] sake of distinction. When the prince heard of this noble deed he was determined not to be outdone in generosity, but insisted upon Audley’s accepting a further grant of 600 marks per annum, arising out of his duchy of Cornwall.

The arms of Lord Audley were Gules, fretty or, and those of the four valiant esquires, as borne for many generations by their respective descendants, in the counties of Chester and Rutland, as follows:

Delves. Argent, a cheveron gules, fretty or, between three delves or billets sable.

Mackworth. Party per pale indented, ermine and sable, a cheveron gules, fretty or.

Hawkestone. Ermine, a fesse, gules, fretty or, between three hawks. The hawks were in later times omitted.

Foulthurst. Gules, fretty or, a chief ermine.[57]

Another interesting instance of the granting of arms to faithful retainers, occurs in a deed from William, Baron of Graystock, to Adam de Blencowe, of Blencowe, in Cumberland, who had fought under his banners at Cressy and Poictiers: “To ALL to whom these presents shall come to be seen or heard, William, Baron of Graystock, Lord of Morpeth, wisheth health in the Lord. Know ye that I have given and granted to Adam de Blencowe, an escocheon sable, with a bend closetted, argent and azure, with three chaplets, gules; and with a crest closetted argent and azure of my arms; to have and to hold to the said Adam and his[Pg 35] heirs for ever; and I, the said William and my heirs will warrant to the said Adam the arms aforesaid. In witness whereof, I have to these letters patent set my seal. Written at the castle of Morpeth, the 26th day of February, in the 30th year of the reign of King Edward III, after the Conquest.”[58]

The practice of devising armorial bearings by will is as antient as the time of Richard II. In some cases they were also transferred by deed of gift. In the 15th year of the same reign Thomas Grendall, of Fenton, makes over to Sir William Moigne, to have and to hold to himself, his heirs and assigns for ever, the arms which had escheated to him (Grendall) at the death of his cousin, John Beaumeys, of Sawtrey.[59]

Notwithstanding the numerous traditions relative to the granting of arms by monarchs in very early times, it seems to have been the general practice before the reigns of Richard II and Henry IV for persons of rank to assume what ensigns they chose.[60] But these monarchs, regarding themselves as the true “fountains of honour,” granted or took them away by royal edict. The exclusive right of the king to this privilege was long called in question, and Dame Julyan Berners, so late as 1486, declares that “armys bi a[Pg 36] mannys auctorite taken (if an other man have not borne theym afore) be of strength enogh.” The same gallant lady boldly challenges the right of heralds: “And it is the opynyon of moni men that an herod of armis may gyve armys. Bot I say if any sych armys be borne ... thoos armys be of no more auctorite then thoos armys the wich be taken by a mannys awne auctorite.”

So strictly was the use of coat-armour limited to the military profession, that a witness in a certain cause in the year 1408, alleged that, although descended from noble blood, he had no armorial bearings, because neither himself nor his ancestors had ever been engaged in war.[61]

It was in the reign of the luxurious Richard II that heraldric devices began to be displayed upon the civil as well as the military costume of the great; “upon the mantle, the surcoat and the just-au-corps or boddice, the charge and cognizance of the wearer were profusely scattered, and shone resplendent in tissue and beaten gold.”[62] Hitherto the escocheon had been charged with the hereditary (paternal) bearing only, but now the practice of impaling the wife’s arms, and quartering those of the mother, when an heiress, became the fashion. Impalement was sometimes performed by placing the dexter half of the lord’s shield in juxta-position with the sinister moiety of his consort’s;[63] but this mode of marshalling occasioned great confusion, entirely [Pg 37]destroying the character of both coats,[64] and was soon abandoned in favour of the present mode of placing the full arms of both parties side by side in the escocheon. Occasionally the shield was divided horizontally, the husband’s coat occupying the chief or upper compartment, and the wife’s the base or lower half; but this was never a favourite practice, as the side-by-side arrangement was deemed better fitted to express the equality of the parties in the marriage relation.

The practice of impaling official with personal arms, for instance, those of a bishopric with those of the bishop, does not appear to be of great antiquity. Provosts, mayors, the kings of arms, heads of houses, and certain professors in the universities, among others, possess this right; and it is the general practice to cede the dexter, or more honourable half of the shield to the coat of office.

Nisbet mentions a fashion formerly prevalent in Spain, which certainly ranks under the category of ‘Curiosities,’ and therefore demands a place here. Single women frequently divided their shield per pale, placing their paternal arms on the sinister side, and leaving the dexter blank, for those of their husbands, as soon as they should be so fortunate as to obtain them. This, says mine author, “was the custom[Pg 38] for young ladies that were resolved to marry!”[65] These were called “Arms of Expectation.”[66]

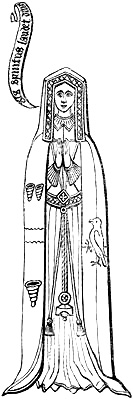

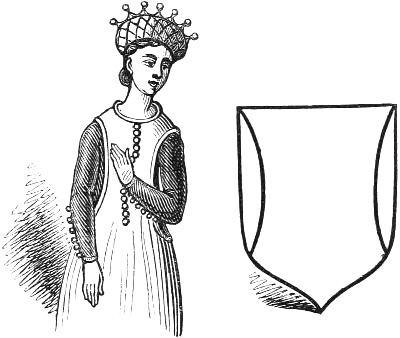

The gorgeous decoration of the male costume with the ensigns of heraldry soon attracted the attention and excited the emulation of that sex which is generally foremost in the adoption of personal ornaments. Yes, incongruous as the idea appears to modern dames, the ladies too assumed the embroidered coat of arms! On the vest or close-fitting garment they represented the paternal arms, repeating the same ornament, if femmes soles, or single women, on the more voluminous upper robe; but if married women, this last was occupied by the arms of the husband, an arrangement not unaptly expressing their condition as femmes-covertes. This mode of wearing the arms was afterwards laid aside, and the ensigns of husband and wife were impaled on the outer garment, a fashion which existed up to the time of Henry VIII, as appears from the annexed engraving of Elizabeth, wife of John Shelley, Esq.[67] copied from a brass in the parish[Pg 39] church of Clapham, co. Sussex. The arms represented are those of Shelley and Michelgrove, otherwise Fauconer; both belonging, it will be seen, to the class called canting or allusive arms; those of Shelley being welk-shells, and those of Fauconer, a falcon.

Quartering is a division of the shield into four or more equal parts, by means of which the arms of other families, whose heiresses the ancestors of the bearer have married, are combined with his paternal arms; and a shield thus quartered exhibits at one view the ensigns of all the houses of which he is the representative. In modern times this cumulatio armorum is occasionally carried to such an extent that upwards of a hundred coats centre in one individual, and may be represented upon his shield.[68] The arms of England and France upon the great seal of Edward III, and those of Castile and Leon in the royal arms of Spain, are early examples of quartering. The first English subject who quartered arms was John Hastings, Earl of Pembroke, in the fourteenth century.

In this century originated the practice of placing the shield between two animals as supporters, for which see a future chapter.

The application of heraldric ornaments to household furniture and implements of war is of great antiquity. I have now before me the brass pommel of a sword on which are three triangular shields, two of them charged with a lion rampant, the other with an eagle displayed. This relic, which was dug up near Lewes castle, is conjectured to be of the reign of Henry III.[69] Arms first occur on coins in one of[Pg 40] Edmund, King of Sicily, in the thirteenth century; but the first English monarch who so used them was Edward III. The first supporters on coins occur in the reign of Henry VIII, whose ‘sovereign’ is thus decorated. Arms upon tombs are found so early as 1144.[70]

Among the ‘curiosities’ of heraldry belonging to these early times may be mentioned adumbrated charges; that is, figures represented in outline with the colour of the field showing through; because the bearers, having lost their patrimonies, retained only the shadow of their former state and dignity.[71]

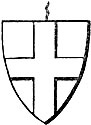

Monasteries and other religious foundations generally bore arms, which were almost uniformly those of the founders, or a slight modification of them.[72] Dallaway traces this usage to the knights-templars and hospitallers who were both soldiers and ecclesiastics. The arms assigned to most cities and antient boroughs are borrowed from those of early feudal lords: thus the arms of the borough of Lewes are the chequers of the Earls of Warren, to whom the barony long appertained, with a canton of the lion and cross-crosslets of the Mowbrays, lords of the town in the fourteenth century. Some of the quaint devices which pass for the arms of particular towns have nothing heraldric about them, and seem to have originated in the caprice of the artists who engraved their seals. Such for example is the design which the good[Pg 41] townsmen of Guildford are pleased to call their arms. This consists of a green mount rising out of the water, and supporting an odd-looking castle, whose two towers are ornamented with high steeples, surmounted with balls; from the centre of the castle springs a lofty tower, with three turrets, and ornamented with the arms of England and France. Over the door are two roses, and in the door a key, the said door being guarded by a lion-couchant, while high on each side the castle is a pack of wool gallantly floating through the air! What this assemblage of objects may signify I do not pretend to guess.

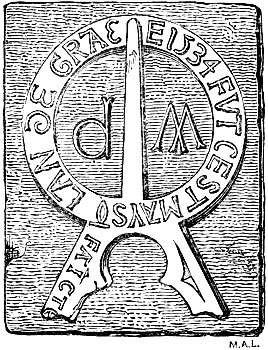

Persons of the middle class, not entitled to coat-armour, invented certain arbitrary signs called Merchants’ Marks, and these often occur in the stonework and windows of old buildings, and upon tombs. Piers Plowman, who wrote in the reign of Edward III, speaks of “merchauntes’ markes ymedeled” in glass. Sometimes these marks were impaled with the paternal arms of aristocratic merchants, as in the case of John Halle, a wealthy woolstapler of Salisbury, rendered immortal by the Rev. Edward Duke in his ‘Prolusiones Historicæ.’ The early printers and painters likewise adopted similar marks, which are to be seen on their respective works.[73] A rude monogram seems to have been[Pg 42] attempted, and it was generally accompanied with a cross, and, occasionally, a hint at the inventor’s peculiar pursuit, as in the cut here given, where the staple at the bottom refers to the worthy John Halle’s having been a merchant of the staple. The heralds objected to such marks being placed upon a shield, for, says the writer of Harl. MS. 2252 (fol. 10), “Theys be none Armys, for every man may take hym a marke, but not armys without a herawde or purcyvaunte;” and in “The duty and office of an herald,” by F. Thynne, Lancaster Herald, 1605, the officer is directed “to prohibit merchants and others to put their names, marks, or devices, in escutcheons or shields, which belong to gentlemen bearing arms and none others.”

At the commencement of the fifteenth century considerable confusion seems to have arisen from upstarts having assumed the arms of antient families—a fact which shows that armorial bearings began to be considered the indispensable accompaniment of wealth. So great had this abuse become that, in the year 1419, it was deemed necessary to issue a royal mandate to the sheriff of every county “to summon all persons bearing arms to prove their right to them,” a task of no small difficulty, it may be presumed, in many cases. Many of the claims then made were referred to the heralds as commissioners, “but the first regular chapter held by them in a collective capacity was at the siege of Rouen, in 1420.”[74]

The first King of Arms was William Bruges, created by Henry V. Several grants of arms made by him from 1439 to 1459 are recorded in the College of Arms.

During the sanguinary struggle between the Houses of[Pg 43] Lancaster and York “arms were universally used, and most religiously and pertinaciously maintained.” Sometimes, however, when the different branches of a family espoused opposing interests they varied their arms either in the charges or colours, or both. The antient family of Lower of Cornwall originally bore “... a cheveron between three red roses,” but espousing, it is supposed, the Yorkist, or white-rose side of the question, they changed the tincture of their arms to “sable, a cheveron between three white roses,”[75] the coat borne by their descendants to this day. The interest taken by the Cornish gentry in these civil dissensions may account for the frequency of the rose in the arms of Cornwall families. The red rose in the centre of the arms of Lord Abergavenny was placed there by his ancestor, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, “better known as the king-maker,” “to show himself the faithful homager and soldier of the House of Lancaster.”[76]

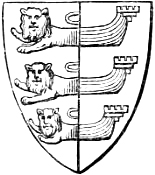

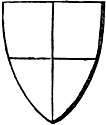

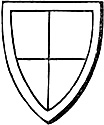

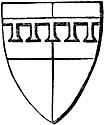

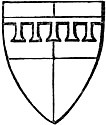

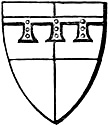

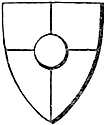

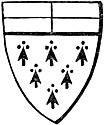

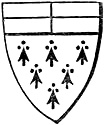

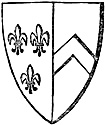

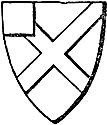

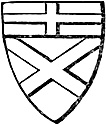

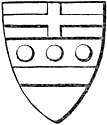

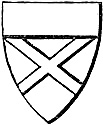

The non-heraldric reader will require a definition of what, in the technical phrase of blazon, are called differences. These are certain marks, smaller than ordinary charges, placed upon a conspicuous part of the shield for the purpose of distinguishing the sons of a common parent from each other. Thus, the eldest son bears a label; the second a crescent; the third a mullet; the fourth a martlet; the fifth an annulet; and the sixth a fleur-de-lis. The arms of the six sons of Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, who died 30o Edward III, were, in the window of St. Mary’s Church, Warwick, differenced in this manner.[77] These distinctions are[Pg 44] carried still further, for the sons of a second son bear the label, crescent, mullet, &c. upon a crescent; those of a third son the same upon a mullet, respectively. In the third generation the mark of cadency is again superimposed upon the two preceding differences, producing, at length, unutterable confusion. Dugdale published a work, in 1682, on the differences of arms, in which he condemns this system, and suggests a return to the antient mode, which consisted in varying the colours and charges of the field, though preserving the general characteristics of the hereditary bearing. For example, Beauchamp of Elmley branched out into four lines; the eldest line bore the paternal arms, Gules a fess, or; the other three superadded to this bearing a charge or, six times repeated, namely,

| II, | Beauchamp of Abergavenny, | 6 cross-crosslets |

| III, | Beauchamp of Holt, | 6 billets, and |

| IV, | Beauchamp of Bletshoe, | 6 martlets, |

|

|

|

|

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. |

and among the further ramifications of the family we find

| V, | Beauchamp of Essex | 6 trefoils slipped |

| VI, | Beauchamp of —— | 6 mullets |

| VII, | Beauchamp of —— | 6 pears, |

[Pg 45]and upwards of ten other coats, all preserving the field gules and the fess or. The Bassets, according to the Ashmolean MSS.[78] varied their coat 7 times, the Lisles 4, the Nevilles 11, and the Braoses 5.

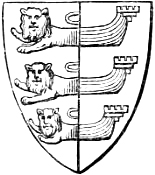

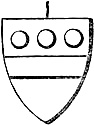

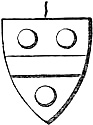

An interesting example of early differencing is cited by Sir Harris Nicolas, in his ‘Roll of Carlaverok.’[79] In the early part of the fourteenth century—

| Leicestershire. | |||

| Barons. | Alan le Zouche bore Gules, besanté Or | ||

| William le Zouche, of Haryngworth | the same with | a quarter ermine | |