The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Noank's Log, by W. O. Stoddard

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Noank's Log

A Privateer of the Revolution

Author: W. O. Stoddard

Illustrator: Will Crawford

Release Date: January 7, 2012 [EBook #38523]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NOANK'S LOG ***

Produced by Al Haines

A PRIVATEER OF THE REVOLUTION

BY W. O. STODDARD

Author of "Guert Ten Eyck," "Gid Granger," etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY WILL CRAWFORD

BOSTON

LOTHROP PUBLISHING COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1900,

BY LOTHROP PUBLISHING COMPANY.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing & Co.—Berwick & Smith

Norwood, Mass. U.S.A.

PREFACE.

The latter half of the year 1776 and the whole of the year 1777 have been vaguely and erroneously described as "the dark hour" of the war for American independence. It is true that our armies, hastily gathered and imperfectly equipped, had been outnumbered and defeated in several important engagements. Beyond that purely military fact there was no real darkness. Upon the sea the success of the Americans had been phenomenal. Before the end of the year 1777, the commerce of Great Britain had suffered losses which dismayed her merchants. As early as the 6th of February, 1778, Mr. Woodbridge, alderman of London, testified at the bar of the House of Lords that the number of British ships taken by American cruisers already reached the startling number of seven hundred and thirty-three. Of these many had been retaken, but the Americans had succeeded in carrying into port, as prizes, five hundred and fifty-nine. The value of these and their cargoes was declared to be moderately estimated at over ten millions of dollars. Only a few of the American cruisers were public vessels, sent out either by individual states or by the United States. All the others were private armed ships, "letters of marque and reprisal" privateers. Something of their character and cruising is set forth in this story of the old whaler Noank, of New London.

Something is also told of the condition and feeling of the people on the land during the misunderstood gloomy days. The years of the Revolutionary War were not altogether years of disaster, devastation, and depression. They were rather years of development and prosperity. The war was fought and its victory won not only for political, but for social, industrial, and financial freedom. All the energies of the American people had been fettered. As the war went on, and without waiting for its close, all these energies became free to work out the great results at which the world now wonders.

We are justly proud of our navy. It was founded by our sailors themselves, without the help of any Navy Department, or Treasury Department, or national shipyards, or naval academies. There were, however, very good admirals, commodores, and captains among the self-taught heroes who went out then in ships in which, ton for ton and gun for gun, they were able to outsail and outfight any other cruisers then afloat.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | A Wounded Nation at Bay |

| II. | More Powder |

| III. | The Unforgotten Hero |

| IV. | The News from Trenton |

| V. | The Brig and the Schooner |

| VI. | The British Fleet |

| VII. | Hunting the Noank |

| VIII. | Contraband Goods |

| IX. | The Picaroon |

| X. | The Black Transport |

| XI. | A Dangerous Neighborhood |

| XII. | A Prize for the Noank |

| XIII. | The Bermuda Trader |

| XIV. | The Neutral Port |

| XV. | A Coming Storm |

| XVI. | Irish Loyalty |

| XVII. | Very Sharp Shooting |

| XVIII. | Down the British Channel |

| XIX. | The Spent Shot |

| XX. | Anchored in the Harbor |

It is well to fix the date of the beginning of a narrative.

Through the mist and the icy rain, with fixed bayonets and steadfast hearts, up the main street of Trenton town dashed the iron men from the frost and famine camp on the opposite bank of the Delaware.

Among their foremost files, leading them in person, rode their commander-in-chief. Beyond, at the central street crossing, a party of Hessian soldiers were half frantically getting a brace of field-pieces to bear upon the advancing American column. They were loading with grape, and if they had been permitted to fire at that short range, George Washington and all the men around him would have been swept away.

Young Captain William Washington and a mere boy-officer named James Monroe, with a few Virginians and Marylanders, rushed in ahead of their main column. Nearly every man went down, killed or wounded, but they prevented the firing of those two guns. Just before their rush, the cause of American liberty was in great peril. Just after it, the victory of Trenton was secure.

So it is set down in written history, and there are a great many curious statements made by historians.

This was a sort of midnight, it is said,—the dark hour of the Revolutionary War.

Manhattan Island, with its harbor and its important military and naval features, had been definitely lost to the Americans and occupied by the British. Its defences had been so developed that it was now practically unassailable by any force which the patriots could bring against it. From this time forward its harbor and bay were to be the safe refuge and rendezvous of the fleets of the king of England. Here were to land and from hence were to march, with only one important exception, the armies sent over to crush the rebellious colonies.

Nevertheless, Great Britain had won back just so much of American land, and no more, as her troops could continuously control with forts and camps. Upon all of her land, everywhere beyond the range of British cannon and the visitation of British bayonets and sabres, the colonists were as firm as ever. It is an exceedingly remarkable fact that probably not one county in any colony south of the Canadas contained a numerical majority of royalists, or "Tories." Still, however, these were numerous, sincere, zealous, and they fully doubled the effective strength of the varied forces sent over from beyond the sea.

The tide of disaster to the American arms had hardly been checked at any point in the north. Fort Washington had bloodily fallen; Fort Lee had been abandoned; the battle of White Plains had been fought, with sharp losses upon both sides. After vainly striving to keep together a dissolving army, General Washington, with a small but utterly devoted remnant, had retreated to contend with cold and starvation in their desolate winter quarters beyond the Delaware.

For a time, the red-cross flag of England seemed to be floating triumphantly over land and sea. All Europe regarded the American cause as hopelessly lost. The American character and the actual condition of the colonies was but little understood on the other side of the Atlantic. The truth of the situation was that the men who had wrested the wilderness from the hard-fighting red men, and who had been steadily building up a new, free country, during several generations, were unaware of any really crushing disaster. At a few points, which most of them had never seen, they had been driven back a little from the sea-coast, and that was about all. Among their snow-clad hills and valleys they were sensibly calculating the actual importance of their military reverses, and were preparing to try those battles again, or others like them. A bitter, revengeful, implacable feeling was everywhere increasing, for several aggravating causes. In the winter days of 1776-77, wounded America was dangerously AT BAY.

It was on Christmas morning, at the hour when the Hessians of Colonel Rahl were giving up their arms and military stores in Trenton town. At that very hour, a group of people, who would have gone wild with delight over such news as was to come from Trenton, sat down to a plentiful breakfast in a Connecticut farm-house. It was a house in the outskirts of New London, near the bank of the Thames River, and in view of the splendid harbor. As yet there were several vacant chairs at the table.

"Guert Ten Eyck," said a tall, noble-looking old woman, as she turned away from one of the frosted windows, "of what good is thy schooner and her fine French guns? Thee has not fired a shot with one of them. How does thee know that thee can hit anything?"

"Yes, we did, Rachel Tarns," was very cheerfully responded from across the table. "We blazed away at that brig. We hit her, too. Good Quakers ought not to want us to hurt people."

"Guert," she tartly replied, "thee has done no harm, I will instruct thee. If thee is thyself a Friend, thee must not use carnal weapons, but if thee is one of the world's people thee may do what is in thee for the ships and armies of thy good King George. Do I not love him exceedingly? Hath he not seized my dwelling for a barracks, and hath he not driven me and mine out of my own city of New York, for what his servants call treasonable utterances?"

"Rachel!" came with much energy from the head of the table. "I can't fight, any more'n you can. You love him just the way you do for pretty good reasons. So do I, for 'pressing my husband and sons into his navy. Thank God! they've all escaped now, and they're ready to sink such ships as they were flogged in—"

"Mother Avery," interrupted a stalwart young man at her side, "that's what we mean to do if we can. British men-o'-war are not easy to sink, though. We've something to think of just now. If our harbor batteries aren't strengthened the British could clean out New London any day. Their cruisers steer out o' range of Ledyard's long thirty-twos, but there's not enough of 'em. We haven't powder enough, either."

"Vine," said Rachel Tarns, "does thee not see the peaceful nature of thy long cannon? They keep thy foes at a distance, and they prevent the unnecessary shedding of blood. I am glad they are on thy fort."

"Rachel Tarns," said Guert, "you gave Aleck Hamilton the first powder he ever had for his field-pieces. You're a real good Quaker. I wish you'd come on board the Noank, though, and see how we've armed her. She's all ready for sea."

"What we're waiting for," said Vine Avery, "is a chance to do something. Father won't say just what his next notion's goin' to be."

"He says he won't wait much longer," said Guert. "Mother, you said I might go with him?"

"You may!" she answered firmly, and then her face grew shadowy.

He was a well-built, wiry looking young fellow, with dark and piercing eyes. His face wore at this moment a look that was not only courageous, but older than his apparent years seemed to call for. It was a look that well might grow in the face of an American boy of that day, whether sailor or soldier.

Others had now come in to fill the chairs at the table. At the end of it, opposite Mrs. Avery, sat a strong looking, squarely built man whom nobody need have mistaken for anything else than a first-rate Yankee sea-captain.

The house they were in was of somewhat irregular construction. Its main part, the doorstep of which was not many yards from the road fence, was a square frame building. At the right of its wide central passage, or hall, was the ample dining room. Opening into this at the rear was a room almost equally large that was evidently much older. Its walls were not made of sawed lumber, nor were they even plastered. They were of huge, rudely squared logs and these had been cut from the primeval forest when the first white settlers landed on that coast. They had made their houses as strong as so many small forts. In the outer doors of this room, and here and there in its thick sides, were cut loopholes, now covered over, through which the earlier Averys could have thrust their gun muzzles to defend their scalps from assaults of their unpleasant Pequot neighbors. There were legends in the family of sharp skirmishes in the dooryard. All of that region had been the battle-ground of white and red men and this was one reason why such captains as Putnam, and Knowlton, and Nathan Hale had been able to rally such remarkably stubborn fighters to march to Breed's Hill and to the New York and New Jersey battlefields.

"What's that, Rachel Tarns, about getting news from New York?" at last inquired Captain Avery, laying down his knife and fork. "I'd ruther git good news from Washington's army. I'm not givin' 'em up, yet, by any manner o' means."

"That's all right, father," said his son Vine, "but I do wish we knew of a supply ship, inward bound. I'd like to strike for ammunition for the Noank and for the batteries. We're not fixed out for a long voyage till we can fire more rounds than we could now."

There was a Yankee drawl in his speech, a kind of twang, but there was nothing coarse in the manners or appearance of young Avery, and his sailor father had an intelligent face, not at all destitute of what is called refinement.

"I wish thee might have thy will," responded Rachel, earnestly.

"Vine!" exclaimed his mother. "Hark! Somebody's coming. Rachel, didn't you hear that?"

"I did!" said Rachel, rising. "That was Coco's voice and Up-na-tan's. The old redskin's talking louder than he is used to about something."

"He can screech loud enough," said Guert. "I've heard him give the Manhattan warwhoop. Coco can almost outyell him, too."

At that moment, the front door swung open unceremoniously, and a pair of very extraordinary human forms came stalking in.

"Up-na-tan!" shouted Guert, with boyish eagerness. "Coco! All loaded down with muskets! What have they been up to?"

"Heap more, out on sled," replied a deep, mellow, African voice. "Ole chief an' Coco been among lobsters. 'Tole a heap."

"Thee bad black man!" said Rachel Tarns. "Up-na-tan, has thee been wicked, too? What has thee been stealing?"

"Ole woman no talk," came half humorously from the very tall shape which had now halted in front of her. "Up-na-tan been all over own island. See King George army. See church prison. Ship prison. See many prisoners. All die, soon. Ole chief say he kill redcoat for kill prisoner. Coco say, too. Good black man. Good Indian."

He might be good, but he was ferociously ugly. The only Indian features discernible about his dress were his moccasons and an old but hidden buckskin shirt. Over this he now had on a tremendous military cloak of dark cloth. On his head was a 'coonskin cap, such as any Connecticut farmer boy might wear. He now put down on the floor no less than six good-looking muskets, all duly fitted with bayonets. Coco did the same, and he, for looks, was equally distinguished. His tall, gaunt figure was surmounted by an undipped mop of white wool, over a face that was a marvel of deeply wrinkled African features. He also wore a military cloak, and both garments were such as might have been lost in some way by petty officers of a Hessian battalion. They were not British, at all events.

Guert glanced at the muskets on the floor and then sprang out of the door to discover what else this brace of uncommon foragers had brought home with them. Just outside the gate there was quite enough to astonish him. It was not a mere hand-sled, but what the country people called a "jumper." It was rudely but strongly made of split saplings, its parts being held together mostly by wooden pins. It had no better floor than could be made of split shingles, and on this lay, now, a closely packed collection of muskets, with several swords, pistols, and a miscellaneous lot of belts, cartridge-boxes, and knapsacks. Coco and Up-na-tan had plainly been borrowing liberally, somewhere or other, and Guert hastened back into the house to get an explanation. Curiously enough, however, both of the foragers had refused to give anything of the kind to the assembly in the Avery dining room.

"Where has thee been, chief?" had been asked by Rachel Tarns. "Tell us what thee and Coco have been doing. We all wish to hear."

"No, no!" interrupted the Indian; "Coco shut mouth. Ole chief tell Guert mother. Where ole woman gone? Want see her!"

"That's so," said Guert. "Mother's about the only one that can do anything with either of them. They used to live a good deal at our house, you know."

There had all the while been one vacant chair at the table, waiting for somebody that was expected, and now through the kitchen door came hurrying in a not very tall but vigorous-looking woman.

"Mother!" said Guert. "So glad you came in! Speak to 'em! Make 'em tell what they've been doing!"

She proved that she understood them better than he or the rest did by not asking either of them a question. She stepped quickly forward and shook hands, with the red man first and then with the black. She stooped and examined the weapons on the floor.

"Sled outside," said Up-na-tan. "Ole woman go see."

Out she went silently, and the dining room was deserted, for everybody followed her. In front of the jumper stood a very tired-looking pony, and she pointed at him inquiringly. He himself was nothing wonderful, but his harness was at least remarkable. It was made up of ropes and strips of cloth. Some of the strips were red, some green, and the rest were blue, the whole being, nevertheless, somewhat otherwise than ornamental.

"Ole chief find pony in wood," said Up-na-tan. "Hess'n tie him on tree. Find sled in ole barn. Hess'n go sleep. Drink rum. No wake up. Ole chief an' Coco load sled. Feel hungry, now. Tell more by and by."

His way of telling left it a little uncertain as to whether or not intemperance was the only cause that prevented the soldier sleepers from awaking to interfere with the taking away of their arms and accoutrements. He seemed, however, to derive great satisfaction from the interest and approval manifested by Mrs. Ten Eyck.

"Come in and get your breakfast," she said. "Rachel Tarns and I'll cook for you while you talk. Rachel, they must have the best we can give them. I've cooked for Up-na-tan. 'Tisn't the first meal he's had here, either. He's an old friend of mine and yours."

"Good!" grunted Up-na-tan. "Ole woman give chief coffee, many time." He appeared, nevertheless, a good deal as if he were giving her commands rather than requests, so dignified and peremptory was his manner of speech. No doubt it was the correct fashion, as between any chief and any kind of squaw, although he followed her into the house as if he in some way belonged to her, and Coco did the same.

"Guert come," he said. "Lyme Avery, Vine, all rest, 'tay in room. Tarns woman come."

The door into the kitchen was closed behind them in accordance with his wishes, and the breakfast-table party was compelled to restrain its curiosity for the time being.

"We must let the old redskin have his own way," remarked Captain Avery. "Nobody but Guert's mother knows how to deal with him. The old pirate!"

"That's just what he is, or what he has been," said Vine Avery. "He hardly makes any secret of it. I believe he has a notion, to this day, that Captain Kidd sailed under orders from General Washington and the Continental Congress."

"Captain Kidd wasn't much worse than some o' the British cruisers," grumbled his father. "They'll all call us pirates, too, and I guess we'd better not let ourselves be taken prisoners."

Mrs. Avery's face turned a little paler, at that moment, but she said to him, courageously:—

"Lyme! Do you and Vine fight to the very last! I'm glad that Robert is with Washington. I wish they had these muskets there! No, they may be just what's wanted at our forts here."

"More muskets, more cannon, and more powder," said Vine. "Oh! how I ache to know how those fellows captured 'em! There isn't any better scout than an Indian, but both of 'em are reg'lar scalpers."

They might be. They looked like it. They were unsurpassed specimens of out and out red and black savagery, with the added advantage, or disadvantage, of paleface piratical training and experience by sea and land. The very room they were now in was a kind of memorial of old-time barbarisms, and it might again become a fort—a block-house, at least—almost any day.

All the farm-houses of Westchester County, New York, not far away, if not already burned or deserted, had become even as so many "block-houses," so to speak. They were to be held desperately, now and then, against the lawless attacks of the Cowboys and Skinners who were carrying on guerilla warfare over what was sarcastically termed "the neutral ground" between the British and American outposts.

The huge fireplace, before which Mrs. Ten Eyck and Rachel Tarns began at once to prepare breakfast for their hungry friends, had an iron bar crossing it, a few feet up. This was to prevent Pequots, Narragansetts, or other night visitors from bringing their knives and tomahawks into the house by way of the chimney. Upon the deerhorn hooks above the mantel hung no less than three long-barrelled, bell-mouthed fowling pieces, such as had hurled slugs and buckshot among the melting columns of the British regulars in front of the breastwork on Bunker Hill, or, more correctly, Breed's Hill. A sabre hung beside them, and a long-shafted whaling lance rested in the nearest corner at the right, with a harpoon for a companion.

All these things had been taken in at a glance by the two foragers, or scouts, or spies, or whatever duty they had been performing most of recently.

"Keep still, Guert," commanded his mother. "Let the chief tell."

Gravely, slowly, in very plain and not badly cut up English, with now and then a word or so in Dutch, Up-na-tan told his story, aided, or otherwise, by sundry sharply rebuked interjections from Coco. The first thing which seemed to be noteworthy was that the British on Manhattan Island considered the rebel cause hopeless. Its armed forces, moreover, were so broken up or so far away that the vicinity of New York was but carelessly patrolled. There had been hardly any obstacle to hinder the going in or the coming out of a white-headed old slave and a wandering Indian. The red men of New York, for that matter, were supposed to be all more or less friendly to their British Great Father George across the ocean. All black men, too, were understood to be not unwillingly released from rebel masters, provided they were not set at work again for anybody else.

Up-na-tan's greatest interest appeared to cling to the forts and to the cannon in them, but he answered Rachel Tarns quite clearly concerning the conditions of the American soldiers held as prisoners. All the large churches were full of them, he said, packed almost to suffocation. One or more old hulks of warships, anchored in the harbor, were as horribly crowded. The worst of these was the old sixty-four gun ship, Jersey, lying in Wallabout Bay, near the Long Island shore. Up-na-tan and Coco had rowed around her in a stolen boat and had been fired upon by her deck guard, and they had seen a dozen at least of dead rebels thrown overboard, to be carried out to sea by the tide.

"Redcoat kill 'em all, some day," said the Indian. "Kill men in ole church. Bury 'em somewhere." He seemed to have an idea that the doomed Americans did not perish by disease or suffocation altogether. He believed that their captors selected about so many of them every day, to be dealt with after the Iroquois or Algonquin fashion. This was strictly an Indian notion of the customary usages of war. It did not stir his sensibilities, if he had any, as it did those of the warm-hearted Quaker woman and Mrs. Ten Eyck. Guert listened with a terribly vindictive feeling, such as was sadly increasing among all the people of the colonies. It was to account for, though not to excuse, many a deed of ruthless retaliation during the remainder of the war. In skirmish after skirmish, raid after raid, battle after battle, the innocent were to suffer for the guilty. Brave and right-minded servants and soldiers of Great Britain were to perish miserably, because of these evil dealings with prisoners of war in and about Manhattan Island.

"Thy scouting among the forts and camps hath small value," said Rachel Tarns, thoughtfully. "If Washington knew all, he hath not wherewith to attack the king's forces."

"No, no!" exclaimed the Indian. "Not now. Washington come again, some day. Kill all lobster. Take back island. Up-na-tan help him. Coco no talk. Ole chief tell more."

Aided by expressive gestures and by an occasional question from Mrs. Ten Eyck, he made the remainder of his story both clear and interesting. He and Coco had crossed the Harlem, homeward bound, in an old dugout canoe. They had worked their way out through the British lines by keeping under the cover of woods, to a point not far from the White Plains battle-field. Here, one evening, they had discovered a Hessian foraging party in a deserted farm-house. The soldiers were having a grand carouse, thinking themselves out of all danger.

"Musket all 'tack up in front of house," said Up-na-tan. "One Hess'n walk up an' down, sentry, till he tumble. Fall on face. Coco find sled in barn. Find pony. Up-na-tan take all musket. Pile 'em on sled. Harness pony, all pretty good. Come away."

"Didn't you go into the house?" asked Guert, excitedly. "Didn't any of 'em know what you were doing? How'd you get your cloak?"

"Boy shut mouth," said Up-na-tan. "Ole chief want cloak. Coco, too, want more musket, pistol, powder. Hate Hess'n. All in house go sleep hard. No wake up. Lie still. Pony pull sled to New London."

Mrs. Ten Eyck's face was very pale and so was that of Rachel Tarns. They believed that they understood only too well why the Manhattan warrior and the grim Ashantee who had been his comrade in this affair, preferred to say no more concerning the undisturbable slumber of that unfortunate detail of Hessians.

"Guert," said his mother, "go in and get your breakfast. The chief and Coco have had theirs. Rachel, you and I must have a talk with Captain Avery."

"Captain Watts, I must say it. I don't a bit like this tryin' to run in without a convoy."

"Nor I either, mate," said the captain, with an upward glance at the rigging and a side squint across the sea. "'Tisn't any fault o' mine. I protested."

"I heard ye," replied the mate. "They only laughed at us. They said the king's cruisers'd swep' these waters as clean as the Channel. Glad ye know 'em."

"Know 'em?" laughed Captain Watts. "I'm a Massachusetts man. I know 'em like a book. Don't need any pilot."

"How 'bout Hell Gate, when we get there? We've lost a ship or two—"

"Brackett, man," interrupted the skipper, more seriously, "that's a long reach ahead, yet. I know Hell Gate channel when we get there. Our risks'll be in the sound. The rebels haven't any reg'lar cruisers. What we've to look out for is the Long Island whaleboat men. Tough customers. They say nigh half on 'em are redskins,—Indian scalpers."

"Well! As to them," said the mate, "we can beat 'em off. Our four-pounder popguns'd be good against whaleboats but not for anything bigger."

"Six on 'em," said Captain Watts. "We can handle 'em, too."

"I'd rather 'twas a frigate," said the mate. "Our crew's none too strong, and half of 'em are 'pressed men. No fight in 'em."

"Oh, yes, they'll have to fight," was responded. "Fight or hang, perhaps. I hate a 'pressed man. Anyhow, it'll take a better wind than this to show us Hell Gate channel before day after to-morrow. We'll be tackin' about in the sound, to-night."

"It's a'most a calm! Bitter cold, too."

He was a very intelligent looking British sailor, that first mate of the Windsor. She was a bark-rigged vessel of possibly six hundred tons, and she was freighted heavily with military and other supplies for the king's forces at New York.

Somehow or other, the discontented mate could not say why or how, the Windsor had become separated from her convoy and consorts. These were seeking their harbor by way of Sandy Hook, while she had been sent through Long Island Sound. She was hardly in it yet, although it may be a wide water question as to precisely at what line the sound begins. Not a sail of any kind larger than a fisherman's shallop was in sight. There was solid comfort to be had in the knowledge that the Americans had no navy, and that all these waters were regularly patrolled by English armed vessels. It looked as if there could be no good cause for anxiety, and Mate Brackett was compelled to accept the situation. He turned away, and the captain himself went below, hopefully remarking:—

"Cold weather's nothin'. There'll be more wind, by and by. We'll be ready to take it when it comes."

"He's a prime seaman. No doubt o' that," said the mate, looking after him. "He's pilot enough, too, and our bein' here's no fault o' his. We'll be ready for any rebel boats, though. I'll cast loose the guns, such as they are, and I'll get up powder and ball. Grapeshot'd be the thing for boats. Sweep 'em at short range. This 'ere craft's goin' to reach port, if we fight our way in!"

He was showing pretty good judgment and plenty of courage. His six guns, three on a side, looked serviceable. The crew appeared to be numerous enough to handle so few pieces as that, whatever their other deficiencies might be. Part of them, indeed were first-rate British tars, the best fighters in the world. As for Captain Watts, he was understood to be an American Tory of the strongest kind, to be depended upon even more than if he had been a Hull man or a Londoner. No set of men, anywhere, ever showed more self-sacrificing devotion to their political principles than did the loyalists, or royalists, of America in their long, fruitless struggle with what they deemed treason and rebellion.

It is possible that Mate Brackett might have studied his cannon and their capacities even more carefully than he did, if at that morning hour he could have been for a few minutes one of a little group upon the deck of a craft that was at anchor in New London harbor.

The tonnage of this vessel was much less than that of the Windsor, but she was sharper in the nose, cleaner in the run, trimmer, handsomer. She was schooner-rigged, with tall, tapering, raking masts that promised for her an ample spread of canvas. She was, in short, one of the new type of vessels for which the American shipyards were already becoming distinguished. She had been built for the whale-fishery, and that meant, to the understanding of Yankee sailors, that she was to have speed enough to race a school of runaway whales, strength to stand the squeeze of an icefloe, the bump of an iceberg, or the blast and billows of a hurricane. She must also have fair stowage room between decks and in her hold for many casks of oil.

"Up-na-tan like long guns," said one of the voices on the deck of the Noank. "Now! Coco swing him. No man help. One man swing. All 'tan back. Brack man try."

He was asking a practical question as an experienced gunner. It was necessary to know whether or not the pivoting of that long, brass eighteen-pounder had been perfectly done for freedom of movement. In action there would be men enough to handle it, but even the work of many hands should not be impeded by overtight fittings and needless frictions.

"Ugh! Good!" he exclaimed, as his black comrade turned the gun back and forth, and then he tried it himself.

"Captain Avery, that's so, he can do it," remarked Guert Ten Eyck, thoughtfully, "but those two are made of iron and hickory. It isn't every fellow can do what they can."

"No, I guess not," laughed Captain Avery.

"I'm glad the old Buccaneers are pleased, though. There goes the redskin to the other guns. He can't find any fault with 'em. Not one of 'em's a short nose."

Three on a side, polished to glittering, the long brass sixes slept upon their perfectly fitted carriages. Every one of them bore the mark of the fleur de lis, for they were of a pattern which the French royal foundries were turning out for the light cruisers of King Louis. Such of them as were already mounted in that manner were lazily waiting for a formal declaration of war with England. These here, however, and others like them, were already carrying on that very war. Before a great while, the entire French navy was to become auxiliary to that of the United States, and considerable French land forces were to march to victory shoulder to shoulder with the Continentals under General Washington.

The sailor comrades of Up-na-tan and Coco were evidently well aware that the savage-looking couple had seen much sea service upon armed vessels. The less said about it the better, perhaps, but some of it had been upon British cruisers, in whatever manner it had been escaped from. Some of it had been, it was said, under a very different fighting flag. Their inspection of the broadside guns was therefore watched with interest.

"Long!" said Up-na-tan. "Good. Shoot bullet far. Not big enough. Want nine-pounder. Old chief like big gun. Knock hole in ship. Sink her quick."

"Take out cargo first," muttered Coco.

"Then sink ship. Not lose cargo."

"Jest so!" exclaimed Captain Avery. "That's what we'll do! Chief, I believe the frame of the Noank is strong enough to carry a long thirty-two and six eighteens."

"No!" replied the Indian, firmly. "Too much big gun 'poil schooner. No run fast any more."

According to the red man's judgment, therefore, the Yankee skipper's enthusiasm might lead him to overload his swift vessel or make her topheavy in a sea. It was likely that things were just as well as they were. At all events, her brilliant armament and her disciplined ordering gave her an exceedingly efficient and warlike air as she rode there waiting her sailing orders.

"Sam Prentice's boat!" suddenly called out a voice, aft. "Father, he's headed for us. Here he comes, rowing hard!"

"Noank ahoy!" came across the water, from as far away as a pair of strong lungs could send it. "I say! Is Lyme Avery aboard?"

"Every man's aboard! All ready! What news?" went back through the speaking trumpet in the hands of Vine Avery, at the stern.

"Tell him to h'ist anchor! British ship sighted away east'ard! Not a man-o'-war. 'Rouse him!"

"All hands up anchor!" roared Captain Avery. "Run in the guns! Close the ports! Gear that pivot-gun fast! Up-na-tan, that's your work."

"Ugh!" said the Indian. "Shoot pretty soon."

Vine and Sam Prentice were exchanging messages rapidly as the rowboat came nearer. All on board could hear, and now the trumpeter turned to note the eager, fierce activity of the old Manhattan.

"It does you good, doesn't it," he said. "You're dyin' for a chance to try your Frenchers."

"Ugh!" grunted the chief, patting the pivot-gun affectionately. "Sink ship for ole King George. Kill plenty lobster! Kill all captain! Whoo-oo-oop!"

His hand was at his mouth, and the screech he sent forth was the warwhoop of his vanished tribe,—if any ears of white men can distinguish between one warwhoop and another. That he had been a sailor, however, was not at all remarkable. All of the New England coast Indians and the many small clans of Long Island had been from time immemorial termed "fish Indians" by their inland red cousins. The island clans were also known as "little bush" Indians. All that now remained of them took to the sea as their natural inheritance, and their best men were in good demand for their exceptional skill as harpooners.

The anchor of the Noank was beginning to come up when the boat of Sam Prentice reached the side.

"Did you sight her yourself, Sam?" asked Captain Avery.

"Well, I did," said Sam. "I was out more scoutin' than fishin', and I had a good glass. She's a bark, heavy laden. It's a light wind for anything o' her rig. She can't git away from our nippers. I didn't lose time gettin' any nigher. I came right in."

"On board with you," said the captain. "It's 'bout time the Noank took somethin'. We've been cooped up in New London harbor long enough."

"That's so!" said Sam Prentice, as he scrambled over the bulwark. "I'm hungry for a fight myself."

He was a wiry, sailorlike man, of middle age, with merry, black eyes which yet had a steely flash in them. Up came the anchor. Out swung the booms. The light wind was just the thing for the Noank's rig, and every sail she could spread went swiftly to its place. She was a beauty when all her canvas was showing. A numerous and growing crowd was gathered at the piers and wharves, for Sam Prentice's news had reached the shore also. Cheer after cheer went up as the sails began to fill.

"Anneke Ten Eyck!" exclaimed Mrs. Avery. "I'm so glad Lyme was all ready. He didn't have to wait a minute after Sam got there."

"I'm glad Guert's with him," said Mrs. Ten Eyck. "If he wants to be a sea-captain, I won't hinder him."

"God be with them all!" was the loud and earnest response of Rachel Tarns. "I trust that they may do their whole duty by the ships of the man George, who calleth himself our king."

"Lyme Avery's jest the man to 'tend to that," called out a deep, hoarse voice, farther along the pier. "He was 'pressed, once, by George's men, and he means to make 'em pay for his lost time."

"So was my son, Vine," said Mrs. Avery. "He has something more'n lost time to make 'em account for."

"Nearly forty New London boys were 'pressed, first and last," said a sad-faced old woman. "One of mine fell at Brooklyn and one's in the Jersey prison-ship. It's the king's work."

"We're sorry for you, Mrs. Williams," said another woman. "I don't know where mine are. We can't get any word from our 'pressed boys. God pity 'em!—God in heaven send success to the Noank and Lyme Avery! To our sailors on the sea and our soldiers on the land!"

"Amen!" went up from several earnest voices, and then there was another round of hearty cheers.

Away down the broad harbor the gallant schooner was speeding, with Guert Ten Eyck astride of her bowsprit. Up-na-tan and Coco were crouching like a pair of tigers at the side of the pivot guns. The crew was both numerous and well selected, for it consisted of the pick of the New London whaling veterans. The majority of them, of course, were middle aged or even elderly, so many of the younger men had marched away with Putnam or were at this time garrisoning the forts of the harbor.

There was to be no long and tiresome waiting. Hardly was the Noank well out beyond the point at the harbor mouth before Sam Prentice, from his perch aloft, called down to his friends on the deck:—

"I've sighted her! She's made too long a tack this way for her good. We'll git out well to wind'ard of her. She's sure game!"

Every seaman on board understood just what that meant, and he was answered by a storm of cheers. Nevertheless, the face of Captain Avery was serious, for he had no means of knowing what might really be the strength and armament of the stranger.

As for her, she had all sail set, and her skipper was at the helm, while Mate Brackett was in the maintop taking anxious observations.

"Sail to wind'ard," he said to himself. "Hope there's no mischief in her. Anyhow, I'll go down and have Captain Watts send the men to quarters."

Down he went and reported, and Captain Watts responded vigorously.

"Most likely a coaster," he said, "but we won't take any chances. Call the men. Any but a pretty strong rebel 'll sheer away if she finds we're ready for her. We'll shoot first, Brackett. I'm a fightin' man—I am!"

"All right, sir," said Brackett, more cheerily. "I've served on a cruiser. Men! All hands clear away for action! Cast loose the guns!"

He was in right good earnest, like the brave British seaman that he was, and the supply ship, in spite of having too much deck cargo, soon began to take on a decidedly warlike appearance. There was no audible grumbling among her crew as they went to their posts of duty, but a sharp observer might have noted that several of them, from time to time, cast wistful glances landward and then looked gloomily into each others' faces.

"No hope!" muttered one of them.

"They are hanging deserters," hissed another. "I saw one run up."

"I saw one flogged to death," came savagely from a third, "but I'll take my chance if I git one."

Mate Brackett was now busy with his glass, and he was telling himself how much he longed for a stronger breeze, coming from some other point of the compass.

"Hurrah!" he suddenly sang out. "Captain Watts, we're all right, now! British flag!"

"Keep to your guns!" roared back the captain. "I'll stand away from her, just the same. If you throw away the Windsor I'll have you hung!"

More fiercely vehement than ever became now his apparent readiness for fighting. He called another man to the wheel and went out among the guns. He ordered up more muskets, pistols, pikes, cutlasses, and armed himself to the teeth, as if to repel boarders.

"They'd call me a Tory," he said to the mate. "They shoot Tories. I'm fighting for my life, if that there sail is a Yankee. Her flag's as like as not a trick to keep us from getting ready."

"We'll be ready," replied the mate; but all the men had heard the remark of Captain Watts concerning his chances.

Nearer and nearer, before the somewhat freshening breeze, came the strange schooner, with the merchant flag of Great Britain fluttering out to declare how peaceable and friendly was her character. Mate Brackett's glass could as yet discover no sign of evil, unless' it might be that a widespread old sail which he saw on the deck amidships had been put there to cover up the wrong kind of deck cargo.

"She hasn't any business that I know of to head for us," he said to his commander, suspiciously. "We must be ready to give her a broadside."

"Luff!" instantly sang out Captain Watts to the man at the helm. "They can't fool me! Brackett, no nonsense, now! Bring the larboard guns to bear! I'll hail her! Ship ahoy! What schooner's that?"

His hail was given through his trumpet, and no answer came during a full half minute, while the schooner sped nearer. Then suddenly a storm of exclamations arose from the men, and Brackett groaned aloud.

"Just what old Watts was afraid of!" he exclaimed. "He's a gone man! So are all of us! The rebel flag! Guns!"

The Noank was indeed flying the stars and stripes now, instead of the red-cross flag of England. The old sail amidships had been jerked away, and there stood Up-na-tan, with one hand upon the breech of his long eighteen and the other holding a lighted lanyard ready to touch her off. Open at the same moment went the three starboard ports, and out ran the noses of the dangerous six-pounders.

"Heave to, or I'll sink ye!" came fiercely down the wind. "Surrender, or I'll send ye to the bottom!"

"It's no use, Captain Watts," said Brackett, dolefully; "she carries too many guns for us. We may as well give up."

"Men!" shouted the captain, "what do you say? Are you with me? Shall we fight it out? I'm ready!"

"Not a man of us, captain," sturdily responded one of the crew. "This 'ere isn't nothin' but a supply ship. We ain't bound as if 'twas a man-o'-war. No use, either."

"Brackett," said Watts, "you may haul down the flag, then. I won't. I call you all to witness that I've done my duty! Mate, the rebels won't shoot you. Report me dead to Captain Milliard of the Cleopatra. He ordered me to run in through the sound against my will."

"I'll give a good report of you," hurriedly responded the mate, while other and not unwilling hands hauled down the flag; "but that long eighteen alone would be too much for our popguns."

The two ships were now near enough for grappling, and in a few minutes more they were side by side upon the quiet sea.

"I surrender to you, sir," said Captain Watts to Captain Avery, as the latter sprang on board, followed by a swarm of brawny whalemen. "I claim good treatment for my men, whatever you may do to me."

"I know you, sir," said Avery, sternly. "You are Watts, the Marblehead Tory. Step aft with me. There's an account to settle with you. Sam Prentice, look out for the prisoners. Vine, get ready to cast off and head for New London. Send 'em all below—"

"All but some of 'em," said Sam, with a broad grin. "Men! Every 'pressed American step out!"

No less than nine of the Windsor's crew obeyed that order, while all the rest sullenly surrendered their useless weapons to Coco and Guert Ten Eyck and a couple of sailors who were ordered to receive them.

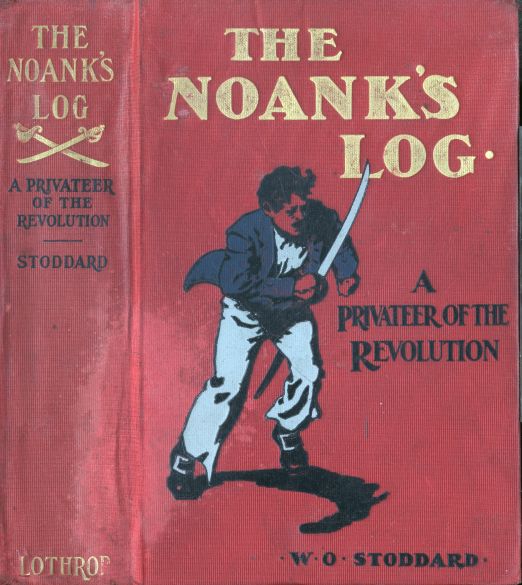

Not on deck, fore or aft, but down in the cabin did the skipper of the captured supply ship give his account of himself and his cargo. Hardly was the cabin door shut behind them before Captain Avery laughed aloud, inquiring:—

"Now, Luke Watts, how did ye make it out! They'll hang ye, yet."

THE MARBLEHEAD TORY.

"'Now, Luke Watts! they'll hang ye yet,' said Captain Avery."

"No, they won't," said Watts. "I've taken across ship after ship for 'em. I'm a known Tory, ye know. Worst kind. I promised jest sech another good Tory, in London, though, that I'd try and deliver this cargo to the blasted rebels. It's mostly guns, and ammunition, and clothing. I managed to git written orders from Captain Milliard, commandin' our convoy, to run through the Sound, contrary to my advice. You see, he's an opinionated man. I got him swearin' mad, and I had to obey, ye know. It has turned out jest as I warned him it would, and he can't say a word."

"You're a razor!" laughed Avery. "Then you tacked right over within easy reach of us, all reg'lar. Now! What are we to do with the crew? We don't want 'em on shore."

"Well!" said Watts. "The 'pressed men'll jine ye, all of 'em. They hate me like p'ison, for I da'sn't let 'em have a smell of how it really is. Take good care of Brackett, anyhow. He's a prime seaman. He saved one of our fellows from a floggin', once. All the rest o' the crew deserve somethin' better'n prison."

"Prison?" said Avery. "They're not prisoners of war. I don't want 'em, even if they are. I wouldn't hurt a hair o' their heads. I'm no butcher."

"Come on deck, then," said Watts, "and be kerful how you talk anythin' but rough to me."

Up they went, to find both vessels sailing steadily away toward the mouth of the harbor. Already they were so near that a booming cannon from Fort Griswold informed that the Noank's success was joyfully understood on shore.

The crew of the Windsor were now summoned up from their temporary confinement in the hold, and were ordered to get out their own longboat ready for launching. They were told that all British tars were to go free and to make the best of their way to New York or to the first British ship they might meet. The impressed Americans listened in silence, for every man of them knew that in case of his escape, even in this manner, there would be thenceforth a possible rope around his neck. Whether impressed or not, he was considered bound to stick to the British flag, come what might.

"Captain Watts," said the commander of the Noank, "do you demand these men? They are Americans."

"I do demand them," replied Watts. "You have no right to keep them, and they'll all be hung as deserters."

"They can't help themselves," said Captain Avery, furiously. "Sam Prentice, iron every one o' those 'pressed men and put 'em all down in the hold. If they try to git away, shoot 'em. I'll put 'em ashore or kill 'em. You can't have 'em, Watts."

"That saves 'em," whispered Watts to himself. "He's another razor. I can report jist how they were took."

At all events, not one of the nine Americans made any resistance which called for shooting him.

"Now, Luke Watts," said the angry American privateer captain, "it's your turn. You are taken in arms against your country. Sam Prentice, Levi Hotchkiss, Vine Avery, speak out! Shall we hang Luke Watts? Or shall we shoot him? Or shall we let him go?"

"We can't safely let him go," began Sam. "He's a dangerous traitor."

"I protest!" interrupted Mate Brackett, courageously. "He has only done his duty to his king. He wasn't even serving on a ship of war. You haven't any right to hang him."

"You're an Englishman," said Avery. "I didn't ask you. Shut your mouth!"

"I won't!" said Brackett; "not if you shoot me. If you hang Captain Watts, we'll hang a dozen Yankees. We've plenty of 'em, too. It'll be blood for blood!"

"Father," said Vine, "let him go. All the men'd say so."

Behind him at that moment stood Up-na-tan, grinning ferociously, with his glittering long knife out.

"So! So! Up-na-tan!" he snarled. "Take 'calp! No let him go. Knife good! Kill!"

None of the others were doing anything theatrical except the two captains, and all the while the longboat was hurriedly made ready for the short and entirely safe, but probably cold, uncomfortable voyage before them.

"Captain Luke Watts," said his captor, sternly, "I suppose I must let you go. Don't let me ever ketch ye again, though. It's time for us to hang Tories. Brackett, you and your men lower that boat and git into her, short order. Luke Watts can pilot you in. Start along, now. Every man may take his own kit."

"Come on, Captain Watts," said the hearty British sailor. "Your shave's been a narrer one. I thought you was bound for the yardarm, this time."

"I owe you something," replied Watts. "I'll stand by ye, any day."

The queer piece of very good unprofessional acting was played to its ending. The longboat was lowered, the men got into her, with provisions for two days, and away she went, her own sail careening her as if it were in haste to get from under the brazen muzzles of the Noank's French guns.

"It's awful to be a traitor," remarked Sam Prentice, gravely. "Who'd ha' thought it of a Marblehead man!"

"Sam!" said Lyme Avery, and the rest of his remark consisted of his right eye tightly shut and his left eye very wide open.

"Ugh! Good!" chuckled Up-na-tan, and Guert Ten Eyck laughed aloud.

Not for one moment had the subtle, keen-eyed red man been deceived, and Guert had caught the truth of it all from him.

"Not a word, Guert," said Captain Avery. "He may be able to do it again."

"Didn't fool ole brack man," said Coco. "S'pose he 'tone bline? Wen King George 'ply ship tack right for New London, then it's 'cause he was 'tendin' to go right there."

"No talk," said Up-na-tan. "Ole chief like Watt. He bring plenty powder for Noank gun. Fort gun, too. Now schooner go to sea. Good!"

The impressed men were freed of their manacles as soon as the longboat was well away. They could be cheerful enough now, for the prudent management of Lyme Avery had made their necks safe, unless they should be taken by the British from an American armed ship.

Up the broad, beautiful harbor the Noank and her prize sailed merrily, while guns from the fort batteries saluted her and crowds of patriotic New Londoners swarmed upon the piers and wharves to do full honor to so really important a success. At one pier head were gathered all the members ashore of the Avery household.

"There he comes!" exclaimed Mrs. Avery; "Lyme's in that boat; Guert and Vine are with him. Neither of them were hurt."

"I hope there wasn't much fighting," said Guert's mother. "I do so hate to have men killed."

"Anneke Ten Eyck," said Rachel Tarns, "thy wicked son hath once more aided the rebels in stealing a ship from thy good king. Thee has not brought him up well. He needeth instruction or he will become as bad as is the man George Washington himself, God bless him!"

More than one day's work was required to ascertain the full value of the Windsor as a bearer of supplies to the forts and ships of the United States, instead of to those of Great Britain.

"All the things the Noank was short of," Captain Avery said, "are goin' into her now. There isn't any secret to be kept concernin' her sailin' orders, either. She's bound for the West Indies to see what she can do."

Perhaps it was at his own table that his plans and the reasons for them were most thoroughly discussed, but all his crew and their many advisers were satisfied, and a number of prime seamen who were not to go on this trip roundly declared their great envy of those who could.

"Tobacco," they said, "sugar, if it's a home-bound trader. If it's one from England, then Lyme'll get loads o' 'sorted stuff, such as they ship for the West Injy trade."

There were other vessels preparing and some were already at sea. The year, therefore, promised to be a busy one for New London. So it did in a number of other American ports, and it behooved Great Britain to increase, if she could, the number and efficiency of her cruisers.

One continual black shadow rested over the port and town, and that was the great probability of a British attack, at no distant day.

"They've their hands pretty full, just now," people said. "The winter isn't their best time, either, but some day or other we shall see a fleet out yonder, and redcoats and Hessians and Tories boating ashore."

It was an entirely reasonable prediction, but its fulfilment was to be almost unaccountably postponed. When its hour arrived, at last, nearly two years later, New London was in ashes and Fort Griswold was a slaughter-pen.

"Mother," said Guert, on his return to the house from one of his visits to the Noank. "I wish you could go with us to the West Indies, the Antilles. Think of it! Summer all the while!"

"But no oranges, or lemons, or pineapples just now," she said laughingly. "I mean to go, some day. Perhaps you will take me in your own ship."

"Any ship of mine will be your ship," he said. "I wish I had some money to leave with you, now. It's awful to think of your being poor."

"Our New York farm will be of no use to us," she said, "until the king's troops leave the island. I shall be very comfortable here, though, except that I shall all the while be waiting for you to come home again."

Very brave was she, under her somewhat difficult circumstances. All the New London people were kind, especially the Averys, but she expected to be poor in purse for some time to come. As to that, however, she had a surprise in store. That very evening, after dark, Up-na-tan lingered in the kitchen.

"Chief see ole woman," he said. "See nobody but Guert mother."

No sooner were they alone than he pulled from under his captured military cloak a small purse, and handed it to her.

"No Kidd money," he said. "Lobster money. Pay ole woman for King George take farm."

She hesitated a moment, and then she exclaimed:—

"God sent it, I do believe! I'll take it. You won't need it at sea."

"Up-na-tan no want money," he replied contemptuously. "Ole chief go fight. Come back. Go to ole woman house. Own house. Money belong to ole woman."

"Thank you!" she said.

"No," grumbled the Indian; "no thank at all. Up-na-tan good!"

So the conference ended, for he stalked out of the house, and she examined the purse.

"Nearly twenty pounds, of all sorts," she said. "Now I needn't borrow of Rachel for ever so long. I want to let Guert know. He will feel better."

The Indian had but obeyed the simple rules of his training. Any kind of game, however captured, was for the squaw of his wigwam to administer. Her business would be to provide for the hunter as best she could. In former days he had always been free of the Ten Eyck house and farm. It was his. The game he had recently taken was in the form of gold and silver, but there could be no question as to what he was bound to do with it.

Neither he or his Ashantee comrade were inclined to spend much time on shore. Hardly anything could induce them to come away from the keen pleasure they were having in the handling and stowage of much powder and shot. The varied weapons which they examined and put in order were as so many jewels, to be fondly admired and even patted.

If Mrs. Ten Eyck had anything else to depress her spirits she tried not to let Guert know it. All her table talk, when he was there, was brimming with warlike patriotism. Nevertheless, he was her only son and she was a widow. She could not but wish, at times, that he were a soldier instead of a sailor, to belong to the quiet garrison of Fort Griswold, for instance, and to come over to the Avery house now and then.

He was sent for, somewhat peremptorily, one day, not by her but by Rachel Tarns, and when he arrived she herself opened the door for him.

"I am glad thee came so early," she said to him. "I have somewhat to say to thee. Come in, hither."

Very dignified was she, at any time, and he was accustomed to obey her without asking needless questions. He followed her, therefore, as she led on into the parlor, opposite the dining room, the main thought in his mind being:—

"I wish she'd hurry up with it. I want to get back to the Noank, as soon as I've seen mother."

"What is it?" he began, after the door of the parlor closed behind them, but she cut him short.

"I will not quite tell thee," she said. "Some things thee does not need to know. Thy old friend, Maud Wolcott, will be here presently. One cometh with her to whom I forbid thee to speak. After they arrive, thou art to do as I shall then direct thee."

"All right," said Guert. "I don't care who it is. I'll be glad to see Maud, though. She's about the best girl I know. Pretty, too."

Hardly were the words out of his mouth before there came a jingle of sleighbells in the road, and it ceased before the house.

"Remain thee here," said Rachel, as she arose and hurried out.

Guert obeyed, but he went to a window and he saw a trim-looking, two-seated sleigh. A man he did not know was hitching the horse to the post near the gate. The sleigh had brought a full load of passengers, all women.

"That's Maud Wolcott," exclaimed Guert. "The girl that's with her is taller than she is, and she's all muffled up. I can't see her face. How Maud did jump out o' that cutter! The two others are old women. Rachel knows 'em."

The first girl out of the sleigh was in the house quickly. She came like a flash into the parlor and, as her hood flew back, a mass of brown curls went tumbling down over her shoulders.

"Guert!" she said, breathlessly. "I'm so glad you're here! We were told you were going."

"We're going!" said Guert. "We're bound for the West Indies. We've taken one British ship, already. I'm a privateer, Maud! Oh! but ain't I glad to see you again. It's like old times!"

"You're growing," she said. "I wish I could go to sea, or fight the British. We haven't any chance to talk, now."

He might be very glad, but, after all, he seemed a little afraid, and a kind of bashfulness grew upon him as he shook hands with her. She must have been a year younger than he was,—but then, she was so very pretty, and he was only a boy.

Half a dozen questions and answers went back and forth between them, as between old acquaintances, near neighbors. Then the parlor door opened to let in Rachel Tarns and the "all muffled up" girl who had been in the sleigh with Maud. She did not speak to anybody, but went and sat down, silently, at the other window of the parlor.

"Guert," said Rachel, "sit thee down here, by me and Maud. Thee will talk only of what I bid thee, and thee will ask no foolish questions."

"All right," said Guert. "What is it you want me to say? Maud hasn't told me, yet, half o' what I want to know."

"If thee were older," she said, "thee would have more good sense. I have a reason that I will not tell thee. I wish thee to give me a full account of all thy dealings with that brave man, Nathan Hale. Thee saw him die, and there is no other that knoweth many things that are well known to thee."

"I hate to tell everything," he said.

"Thee must!" exclaimed Rachel. "Thee will not leave out a word that he spake or a deed that he did."

Something flashed brightly into the quick mind of Guert just then. He could not exactly shape it, but it came when he caught the sound of a low sob from under the veil of the girl at the other window. "I'll begin where I first saw him," he said.

He did not at all know after that how his boyish enthusiasm helped him to draw his word pictures of Captain Hale's daring scout work, of boat and land adventures by night and day, in company with him and Up-na-tan and Coco. He told it more rapidly and vividly as a kind of excitement spurred him. He did not know that beyond the half-open door of the next room his mother and several other persons were listening. Two of them had come in the cutter with Maud, and yet another sleigh had brought visitors to the Avery house. There were to be very loving and tenacious memories to treasure all that he was telling.

Guert came at last, sorrowfully, more slowly, to the tragic end of all in the old orchard near the East River. He told of the troops, and the crowd, and the tree, and he repeated the last words of the hero who perished there.

"That I can give but one life for Liberty!" he said, and there his own voice choked him, while a whisper from beyond the door said softly: "Glory! Glory! Glory!"

Throughout Guert's narrative, there had been something almost painful in the forward-leaning eagerness of the veiled girl at the window. She was standing now, and a sigh that was more a sob broke from her as she held out to him a hand with something that she was grasping tightly. Rachel stepped forward and took it, opening it as she did so. Only a small, leather case it was, containing a miniature.

"My boy," said Rachel, "is that like thy friend? Look well at it. Tell me."

"It's a real good picture," said Guert, wiping his eyes as he looked more closely. "It's like him, but there isn't the light and the smile that was on his face when he stood with the rope around his neck under that old apple tree."

"That is enough," said Rachel, turning away with the miniature. "I think not many eyes will ever see this thing again."

"Not any," came faintly from under the veil. "I mean to have it buried with me. Nobody else has any right to it. I must go now."

The girl at the window had risen as she spoke. She came forward and took Guert's hand for a moment. Then, in a voice that was tremulous with feeling, she said:—

"Let me thank you for all you have said. Thank you for your friendship for him. God bless you!"

In spite of its sadness, her voice had in it a half-triumphant tone. Rachel gave her back the miniature, and she turned to go. No one spoke to her. Guert could not have said a word if he had tried, but Maud sprang to her side.

"Good-by, Guert," she said. "I'll see you again, some day. I'm going with her, now."

"Good-by, Maud," said Guert. "I did so want a talk with you, but I s'pose I can't this time. We are to sail right away. The Noank's all ready."

Both of the sleighs at the gate were quickly crowded. They were driven away, and hardly had the jingling of their bells died out up the road, before Rachel Tarns came and put an arm around Guert. She, too, was wiping her eyes.

"Thee was a brave, good boy," she said, "and I love thee very much. Thee is too young, now, and thy picture hath never been painted. Some day thee may need one to give away, as Nathan did. If it shall please God to let thee die for thy country, somebody may will to keep it in memory of thee."

"Mother would," said Guert. "I'll get one, as soon as I can. But Nathan Hale'll be remembered well enough without any picture. All the men in America 'll remember him. He was a hero!"

The voice of Vine Avery was at the front door, shouting loudly for Guert, and out he darted, not even stopping to inquire who of all the friends or family of his hero had been listening in the dining room.

"What is it?" he eagerly asked, as he joined Vine at the doorstep.

"Powder and shot all stowed," said Vine. "Everything's ready now. As soon as the rest of the Windsor's cargo's out, they're going to tow her up the river, out o' harm's way. Father says we're to be all on board, now. Come on!"

"Oh, Guert!" said his mother, for she had followed him, and her arms were around his neck. "I can't say a word to keep you back! Be as brave as Nathan Hale was! God keep you from all harm! Do your duty! Good-by!"

It was an awful struggle for poor Guert, but he would not let himself cry before Vine Avery and the sailors who were with him. All he could do, therefore, was to hug his mother and kiss her. His last good-by went into her ear and down into her heart in a low, hoarse whisper.

Away marched the last squad of the crew of the Noank, and Mrs. Avery stood at the gate and watched them until they were hidden from her eyes beyond the turn of the road.

"What is it, Sam?"

"I guess, Lyme, we'd better hold on a bit. The fort lookout sends word that a British cruiser's in sight, off the harbor."

Sam Prentice was in a rowboat, just reaching the side of the Noank, and his commander was leaning over the rail.

"I'd like to send a shot at her," he said. "None o' those ten-gun brigs, if it's one o' them, carry long guns or heavy ones."

"Can't say," replied Sam. "Maybe it's a bigger feller. He won't dare to run in under the battery guns, anyhow. He can't look into the harbor."

"I wish he would," laughed the captain. "If he's goin' to try a game of tackin' off and on, and watchin', though, we must make out to run past him in the night."

"We mustn't be stuck any longer here," said Sam. "Are all the crew aboard?"

"All but you," was the reply. "Send your boat ashore. We'll find out what she is. I won't let any single cruiser keep me cooped up in port, now my powder and shot's found for me. We'll up anchor, Sam."

The first mate of the Noank, for such he was to be, came over the rail, and his boat was pulled shoreward.

"Isn't she fine!" he said, as he glanced admiringly around him. "We're in good fightin' order, Lyme."

"Sam," said the captain, "just study those timbers, will ye. Only heavy shot'd do any great harm to our bulwarks. I had her built the very strongest kind. Now! Some o' the new British craft are said to be light timbered, even for rough weather. Their own sailors hate 'em, and we can take their judgment of 'em."

"It's likely to be good," said Sam. "What a British able seaman doesn't know 'bout his own ship, isn't worth knowin'."

Further talk indicated that they both held high opinions of the mariners of England. Against them, as individuals, the war had not aroused any ill feeling. There was, indeed, among intelligent Americans, a very general perception that King George's war against his transatlantic subjects was anything but popular with the great mass of the overtaxed English people. It was a pity, a great pity, that stupid, bad management and recklessly tyrannical statesmanship, in a sort of combination with needless military severities, had done so much to foster hatred and provoke revenge. It was true, too, although all Americans did not know or did not appreciate it, that their side of the controversy had been ably set forth in the Parliament of Great Britain by prominent and patriotic Englishmen, such as Chatham and Colonel Barre.

The old whaler Noank, of New London, however, had now become an American war vessel. Her crew and her commander were compelled, henceforth, to regard as enemies the captains and the crews of all vessels, armed or unarmed, carrying the red-cross flag instead of the stars and stripes.

"I tell you what, Sam," remarked Captain Avery, at last, "I wish we had news from New York and from Washington's army. The latest we heard of him and the boys made things look awfully dark."

"Don't let yourself git too down in the mouth!" replied Sam. "I guess the sun'll shine ag'in, Sunday. It's a long lane that has no turnin'. Washington's an old Indian fighter. He's likely to turn on 'em, sudden and unexpected, like a redskin on a trail that's been followed too closely."

"It won't do to go after a Mohawk too far into the woods, sometimes," growled Avery. "Not onless you're willin' to risk a shot from a bush. Now, do you know, I wish I knew, too, what's been the dealin' of the British admirals with Luke Watts, for losin' the Windsor. We owe that man a good deal,—we do!"

"They won't hurt him," said Sam. "It wasn't any fault o' his'n."

In some such manner, all over the country, men and women were comforting themselves, under the shadow of death which seemed to have settled down over the cause of American independence. They knew that the Continental army was shattered. It was destitute, freezing, starving, and it was said to be dwindling away.

Somewhere, however, among the ragged tents and miserable huts of its winter quarters, was a man who had shown himself so superior to other men that in him there was still a hope. From him something unexpected and startling might come at any hour.

As for Luke Watts, formerly the skipper of the British supply ship Windsor, now a prize in New London harbor, Captain Avery and his mate spoke again of him and of the difficulties into which he might have fallen. Possibly it would have done them good to have been near enough to see and hear him at that very hour of the day.

A good longboat, with a strong crew anxious to make time and get into a warmer place, had had only a short run of it from New London to New York. Here was Luke, therefore, in the cabin of a British seventy-four, standing before a gloomy-faced party of naval officers. With him were his mate, Brackett, and several of the sailors of the Windsor. It was evident that her loss had been inquired into, and that all the testimonies had been given. If this was to be considered as a kind of naval court martial, it was as ready as it ever would be to declare its verdict.

"Gentlemen," said the burly post-captain who appeared to be the ranking officer, "it's a bad affair! We needed that ammunition. Even the land forces are running so short that movements are hindered. If, however, we are to find fault with any man, we must censure the captain of the Cleopatra. This man Watts is proved to have gone into the Sound against his will and protest. I am glad that the rebels did not hang him. His recorded judgment of the danger to be encountered was entirely correct. Watts, I shall want you to pilot home one of our empty troop-ships."

"I know her, sir," replied Luke, promptly. "I beg to say no, sir. Not unless she has twice the ballast that's in her now. I'd like permission to say a word more, sir."

"Speak out! What is it?"

"A ten-gun brig in the Sound can't catch that New London pirate—"

"The Boxer is cruising around that station," interrupted the captain. "She's a clipper to go."

"No use," said Luke, shaking his head. "The old whaler'll get away."

"What would you do, then?" roughly demanded another officer.

"A strong corvette, or two of 'em, off Point Judith and Montauk, to catch her as she runs out," said Luke. "She'll fight any small vessel. She carries a splendid pivot-gun, and she has six long sixes. She will be handled by prime seamen."

"Gentlemen," remarked the captain, "I agree with him. We have found the advice of this man Watts to be correct in every case. I believe he is right, now. We must do as he says or that pirate, perhaps others with her, will escape us. I will put him in charge of the Termagant. I'll feel safer about her, if she is sailed home by a man with a rebel rope around his neck."

There was a general expression of assent, and then Watts spoke again.

"I want Brackett, if I can have him," he said. "I never had a better mate. There's fight in him, too."

"You may have him," he was told, and several of the officers present expressed their great regret that so many impressed American seamen had been ironed by Captain Avery and compelled to escape from a return to man-of-war duty. They ought never to have been detailed, it was asserted.

"We can't hang 'em for desertion," they said, half jocularly. "All we could do, if we caught them, would be to set them at work again."

Nevertheless, four of these escaped men were now voluntarily among the crew of the Noank. The remaining five had preferred to make the best of their ways to their several homes. Not one of them all had chosen to seek the friendly shelter of the British navy, so near and so ready to receive them.

Luke Watts and his friends were dismissed and went on deck. Shortly afterward, their own longboat carried them to the Termagant troop-ship, and the first words uttered by the Marblehead skipper after reaching her, were duly reported to his superiors.

"Men!" he had exclaimed, as he glanced around him. "This thing isn't fit to go to sea. She's been handled by lubbers. We've work before us, if we don't want to go to the bottom or be overhauled by the Yankees. Jest look at her spars and riggin'!"

All things were working together, therefore, to strengthen the confidence reposed in him, in spite of the curious fact that he had skilfully delivered the Windsor and her cargo in New London instead of in New York.

"We had a narrer escape not many miles beyond Hell Gate," he had reported. "One o' those Long Island buccaneer whaleboats chased us more 'n an hour. They gave it up then, and we got through. 'Twas a close shave. Half on 'em are Montauk and Shinnecock redskins. Reg'lar scalpers."

He had told the truth, as he had appeared to do at every point of the account which he had given of himself, and now the very men who had captured him and let him go, neglecting to hang him, were about to learn why that Long Island whaleboat had not followed him any farther. There had been plenty of time for such a boat to get away, a long distance.

The lookout on the rampart of Fort Griswold, the same keen-eyed watcher who had sent warning to the Noank of the danger in the offing, was busy with his telescope.

"The cruiser's a brig!" he sang out. "I can make her out, now. She's one o' the new patterns. She's chasin' a whaleboat. I wish she'd roller it onto one o' them there ledges. She's firin'. It's long range, but it looks kind o' bad for the Long Islanders. There ain't any of our boats out, to-day. It's from t'other shore."

He was watching, now, with intense excitement. There is hardly anything else so interesting as a chase at sea with cannonading in it. All this time, however, Captain Lyme Avery had been growing feverish. He knew nothing of Luke Watts, nothing at all of the Long Island whaleboat and her pursuer, but he shouted to the men at the capstan:—

"Heave away, boys! I'm goin' to have a look at that there Britisher. We won't run any fool risks but we'll find out what she is, anyhow."

Hearty cheers answered him and a loud war-whoop from Up-na-tan, for every man on board had long since become sick of harbor inactivity. They were also all the more ready for a brush with the enemy after having brought in so fine a prize on their first venture, and they now had plenty of powder and shot to fire away.

Only the mainsail swung out after the anchor was raised, but a fair wind was blowing and the Noank went swiftly seaward with the tide in her favor.

"Hark!" said Sam Prentice; "guns again! Something's up, Up-na-tan! Oh, you and Coco are at your pivot-gun! Free her! Have her all ready. She's the only piece on board that's likely to be of any use."

"Let 'em alone!" called out Captain Avery. "They know what they're about. They're old gunners. I don't care so much, jest now, 'bout how they got their trainin'. See 'em!"

They were not by any means a handsome pair at any time, and they were several shades uglier than usual. The Ashantee was grinning frightfully, and the teeth he showed must have been filed to obtain so sharklike a pointing. The red man was not grinning, but all the wrinkles in his face seemed to grow deeper and his complexion darker. He was charging his guns with solemnly scrupulous care.

"No miss!" he said. "Up-na-tan find out what big gun good for."

His first charge was going in, therefore, for a purpose of practical inquiry into the character of the long eighteen. The foundries of that day could not manufacture large weapons with mathematical precision. Hardly any two could be said to be exactly alike, except in appearance. It followed that each gun had good or bad features of its own. From ship to ship, throughout the royal navy, the gunners published the qualities of their brazen or iron favorites, and there were cannon of celebrity which old salts would go far to see.

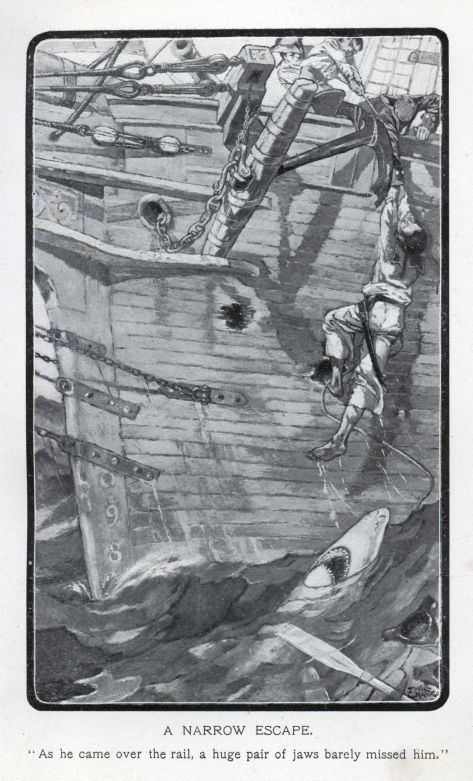

The sound of the British firing came up somewhat dulled against the wind. It was not until they were out of the harbor that the sailors of the Noank discovered how really near were both friends and foes. The latter were still outside of the range of any of the fort guns. Hardly more than a mile and a half nearer was the whaleboat from Long Island. It could be seen that it was full of men, and they were showing splendid pluck, for they were rowing steadily, while every now and then a shot from the brig dropped dangerously near them. One iron bullet, hitting fairly, might knock their frail though swift craft all to pieces. Up went sail after sail upon the Noank, as she speeded along, and an officer on the British cruiser's deck had good reason for the astonishment with which he called out:—

"There she comes! You don't mean to say she's coming out to fight us?"

"It looks like it," responded another officer near him. "We can make match-wood of her if we can get close enough. I wish I knew what her armament is. These Yankees have more impudence!"

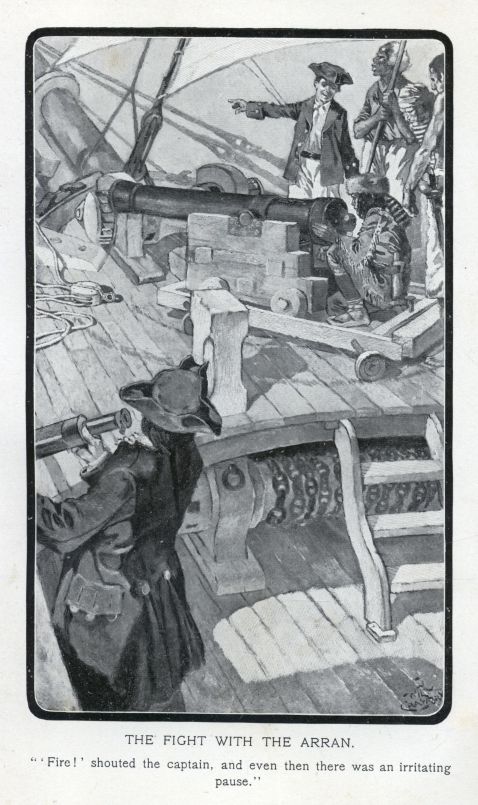

He did not have to wait many minutes before he learned something. The Noank whirled away upon the starboard tack around the point, and, just as she steadied herself upon her new course, out roared her pivot-gun.

Up-na-tan stood erect as soon as he touched off his piece, and he anxiously watched for the results.

"Ugh! whoop!" he shouted triumphantly. "Gun good! Shoot straight! Hit 'em!"

"Right!" said Captain Avery, who had been watching through a glass. "If the old pirate didn't land that shot on her! It's pretty long range, too."

"Load quick, now!" said the Indian. "Ole chief hit her again!"

His assistants were already feverishly busy with their loading, while he stood and proudly patted his cannon, very much as if it deserved praise and could appreciate his approval.