The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Invasion of France in 1814, by

Émile Erckmann and Alexandre Chatrian

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Invasion of France in 1814

Author: Émile Erckmann

Alexandre Chatrian

Release Date: July 26, 2011 [EBook #36859]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE INVASION OF FRANCE IN 1814 ***

Produced by Al Haines

HISTORICAL ROMANCES OF FRANCE

THE INVASION OF

FRANCE IN 1814

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH OF

ERCKMANN-CHATRIAN

ILLUSTRATED

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

NEW YORK::::::::::::::::::::::1911

COPYRIGHT, 1889, 1898

BY CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

ILLUSTRATIONS

The invasion of France by the allied armies after the battle of Leipsic had proved the German campaign even more disastrous than that of Russia the year before, was not only essentially the death-blow to the power of Napoleon, but was the first real taste France had had for many years of an experience she had so often previously meted out to her neighbors. In spite of all she had suffered from the conscription and from exhaustion of men and treasure in offensive war—or at least war waged outside her own territory—the great Invasion meant for her something far more terrible than any reverses she had yet undergone. Napoleon was not only not invincible, it appeared, he was not even able to defend the frontiers he had found firmly established on his accession to power. The allies had announced that they were warring not against France but against the French Emperor—"against the preponderance that Napoleon had too long exercised beyond the limits of his empire." Everywhere in France except in the official world of Paris, the once enchanted name of Napoleon had become recognized as a synonym of national disaster.

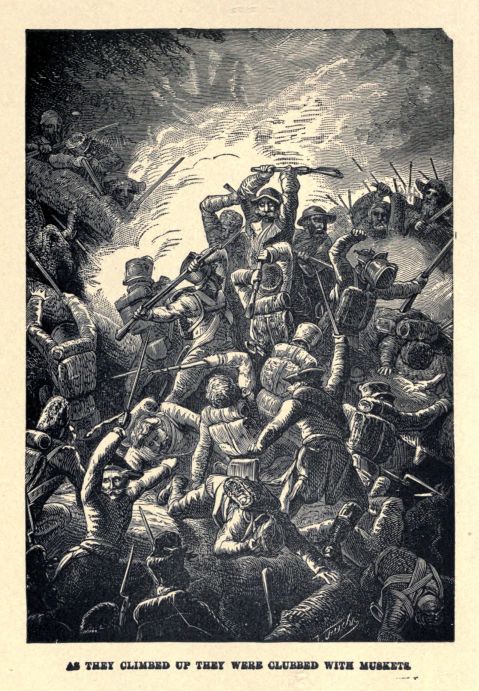

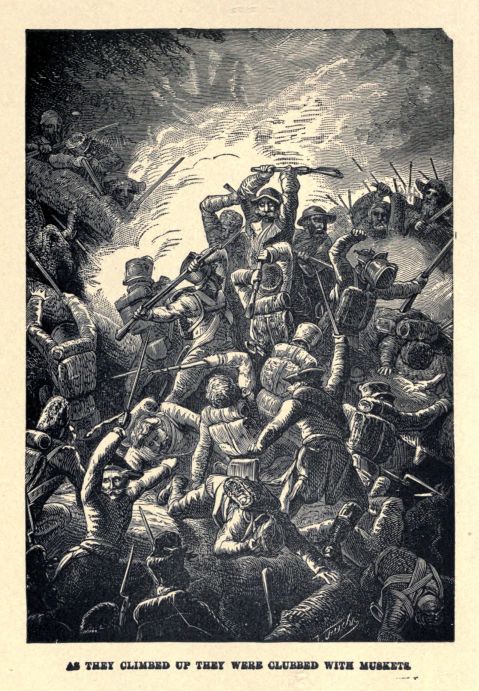

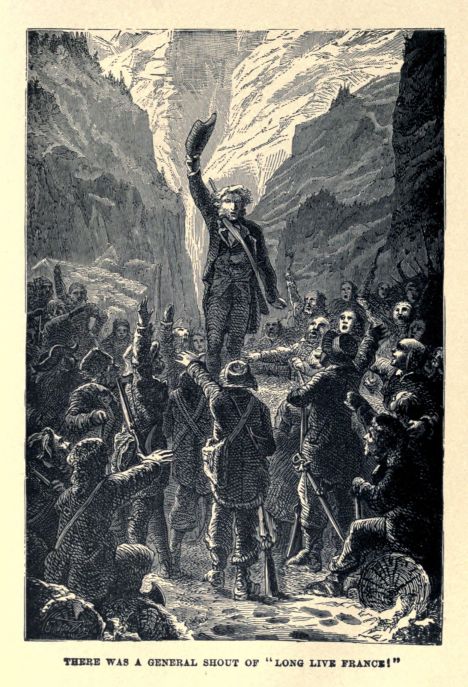

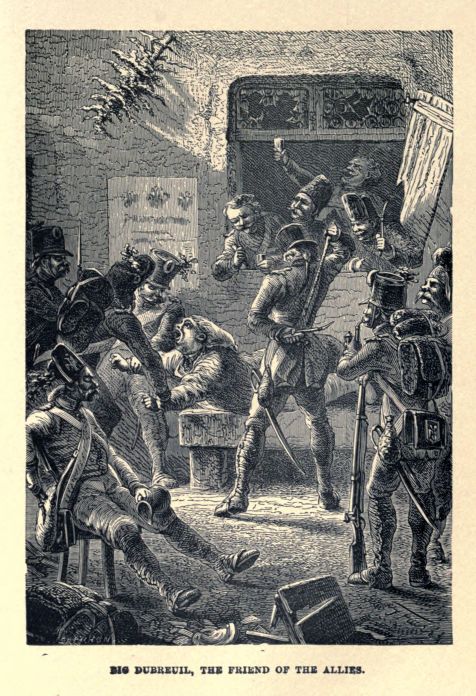

Nevertheless nothing—except, perhaps, the similar circumstances of the Prussian invasion in 1870—has ever so well attested the fundamental and absorbing patriotism of the French people as their heroic resistance to this invasion and their instinctive and universal refusal to separate in this crisis the cause of their Emperor from their own. The presence of a foreign foe on whatever pretext within their boundaries sufficed to arouse them en masse. No such enthusiasm had been known since the days of the Republic's and the Consulate's victories as was awakened, in the thick of national disaster and amid the ruin of all ambitious hopes, by the thought of an enemy within the borders of la patrie. And in "The Invasion" of MM. Erckmann-Chatrian this enthusiasm and devotion find a chronicle which is most realistically impressive. So soon as the peasants of the outlying villages of the eastern frontier learn of the impending descent of the Cossacks and Germans, without thought of their own comfort and safety—which it is, however, impartially pointed out they know would hardly be better secured by submission—they organize for resistance. They blockade the highways and defend the mountain passes. Women and children aid in the work. While the siege of Phalsbourg goes on the heights are occupied by sturdy peasants who oppose for a while an effective obstacle to the passage of the invaders. The worst hardships, the most perilous adventures, are accepted by them with the heroic courage of regulars. Outlaws and smugglers work and fight hand to hand with the respected worthies of the neighborhood. They watch their farms burn from their outlook on the hill-tops, they suffer the pangs of starvation when their supplies are intercepted by the enemy, they fight to desperation when their position is finally turned by the treachery of a crazy German they have long harbored—and whose vagaries give, by the way, a most romantic color to the narrative—and they are finally slain or captured just as Paris capitulates and peace is made. None of the National Novels is more graphic or more significant historically than "The Invasion."

If you would wish to know the history of the great invasion of 1814, such as it was related to me by the old hunter Frantz du Hengst, you must transport yourself to the village of Charmes, in the Vosges. About thirty small houses, covered with shingles and dark-green houseleeks, stand in rows along the banks of the Sarre: you can see the gables carpeted with ivy and withered honeysuckles, for winter is approaching; the beehives closed with corks of straw, the small gardens, the palings, the hedges which separate them one from the other.

To the left, on a high mountain, arise the ruins of the ancient château of Falkenstein, destroyed two hundred years ago by the Swedes. It is now only a mass of stones and brambles; an old "timber-way," with its worn-out steps, ascends to it through the pine-trees. To the right, on the side of the hill, one can perceive the farm of Bois-de-Chênes—a large building, with granaries, stables, and sheds, the flat roof loaded with great stones, in order to resist the north wind. A few cows are grazing in the heather, a few goats on the rocks.

Everything is calm and silent.

Some children, in gray stuff trousers, their heads and feet bare, are warming themselves around their little fires on the outskirts of the woods; the spiral lines of blue smoke fade away in the air, great white clouds remain immovable above the valley; behind these clouds arise the arid peaks of the Grosmann and Donon.

You must know that the end house of the village, whose square roof is pierced by two loophole windows, and whose low door opens on the muddy street, belonged, in 1813, to Jean-Claude Hullin, one of the old volunteers of '92, but now a shoemaker in the village of Charmes, and who was held in much consideration by the mountaineers. Hullin was a short stout man, with gray eyes, large lips, a short nose, and thick eyebrows. He was of a jovial, kind disposition, and did not know how to refuse anything to his daughter Louise, a child whom he had picked up among some miserable gypsies—farriers and tin-sellers—without house or dwelling-place, who go from village to village mending pots and pans, melting the ladles, and patching up cracked utensils. He considered her as his own daughter, and never seemed to remember she came of a strange race.

Besides this natural affection, the good old fellow possessed others still: he loved above all his cousin, the old mistress of the farm of Bois-de-Chênes, Catherine Lefèvre, and her son Gaspard, who had been carried off that year by the conscription—a handsome young fellow, the "fiancé" of Louise, and whose return was expected by all the family at the end of the campaign.

Hullin recalled always with enthusiasm his campaigns of the Sambre-et-Meuse, of Italy and of Egypt. He often thought of them, and sometimes in the evening, when the work was over, he would go to the sawmills of Valtin, that dark manufactory formed of trunks of trees still bearing their bark, and which you can perceive down there at the end of the valley. He sat down among the wood-cutters and charcoal-gatherers, and sledges, in front of the great fire; and while the heavy wheel turned, the dam thundered and the saws grinded, he, his elbow on his knee, and his pipe in his mouth, would speak to them of Hoche, of Kleber, and finally of General Bonaparte, whom he had seen hundreds of times, and whose thin face, piercing eyes, and eagle profile, he would depict as though he were present.

Such was Jean-Claude Hullin.

He was one of the old Gallic stock, fond of extraordinary adventures and heroic enterprises, but constant to his work, out of a sentiment of duty, from New Year's day until Saint Sylvester's.

As for Louise, the child of the tramp, she was a slender creature, with long delicate hands, eyes of such a soft deep blue that they seemed to penetrate to the depths of your soul, skin of a snowy whiteness, hair of a pale straw-color, like silk in texture, and drooping shoulders like those of a virgin praying. Her ingenuous smile, pensive forehead—in fact, her whole appearance—recalled the old Lied of the Minnesinger Erhart, when he said: "I have seen a ray of light pass by: my eyes are still dazzled by it. Was it a moonbeam piercing the foliage? Was it a smile from the dawn in the forests? No, it was the beautiful Edith, my love, who passed by. I have seen her, and my eyes are still dazzled."

Louise only cared for fields, gardens, and flowers. In spring-time, the first notes of the skylark made her shed tears of delight. She went to see the budding hawthorn and blue cornflowers behind the hedges on the hill-sides; she watched for the return of the swallows, from the little windows of the garret. She was always the true child of the homeless vagrants, only less wild. Hullin forgave her everything; he understood her nature, and would sometimes say, laughingly:—"My poor Louise, with the booty that thou bringest us,—thy fine sheaves of flowers and golden wheat-ears—we should die of hunger in three days!"

Then she would smile so tenderly at him and embrace him so willingly, that he would go on with his work, saying:—"Bah! why need I grumble? She is right: she loves the sunshine. Gaspard will work for two—he will have the happiness of four. I do not pity him: on the contrary. One can find plenty of women who work, and that does not improve their beauty; but loving woman! what luck to have found one—what luck!"

Thus reasoned the good old fellow; and days, weeks, and months wore away in the expectation of Gaspard's return.

Madame Lefèvre, an extremely energetic woman, partook of Hullin's ideas on the subject of Louise.

"As for me," she said, "I only want a daughter who loves us; I do not wish her to have anything to do with my household affairs. So long as she is contented! Thou wilt not bother me—is it not so, Louise?"

And then they would embrace each other. But Gaspard did not return, and for two months they had had no tidings of him.

On that same day, toward the middle of December, 1813, between three and four o'clock in the afternoon, Hullin, bending over his bench, was finishing a pair of nailed shoes for the wood-cutter Rochart. Louise had just put an earthenware porringer down on the little iron stove, which sang and crackled in a plaintive manner, while the old clock counted the seconds in its monotonous tic-tac. Outside, all along the street, could be perceived small pools of water, covered with a coating of thin white ice, announcing the approach of intense cold. At times the sound of great wooden shoes, running along the hardened road, could be heard, and a felt hat, a cape, or a woollen cap would pass by: then the noise would cease, and the plaintive hissing of the green wood in the flames, the humming of Louise's spinning-wheel, and the boiling of the porridge-pot again prevailed. This had gone on for about two hours, when Hullin, glancing accidentally through the little window-panes, stopped his work, and remained with his eyes wide open, staring, as though absorbed by some unusual spectacle.

In fact, at the corner of the street, in front of the "Trois Pigeons," there advanced, in the midst of a crowd of whistling, jumping, and shouting boys, who called out "The King of Diamonds! The King of Diamonds!"—There advanced, I say, one of the strangest personages imaginable. Picture to yourself a red-headed, red-bearded man, with a grave face, gloomy expression, straight nose, the eyebrows meeting on the forehead, a circle of tin on the head, a gray dogskin floating over the back, its forepaws tied around the neck; the chest covered with little copper crosses, the legs clothed with a sort of gray cloth trousers fastened above the ankle, and the feet bare. A great raven, with black wings glossed over with white, was perched on his shoulder. From his imposing gait one would have taken him for one of the ancient Merovingian kings, such as are represented by the images of Montbéliard; he held in the left hand a short thick stick in the shape of a sceptre, and with the right he made ostentatious gestures, raising his finger toward heaven, and apostrophizing his retinue.

All the doors opened on his passage; behind every pane appeared inquisitive faces. Some few old women on the outer stairs of their houses, called out to the madman, who would not deign to turn his head; others went down into the streets and tried to prevent him passing; but he, lifting his head and raising his eyebrows, with one word and a sign, forced them to make way.

"Hullo!" said Hullin, "here is Yégof. I did not expect to have seen him again this winter. It is not one of his customs. What on earth can bring him back in such weather?"

And Louise, laying down her distaff, hurried away to contemplate "The King of Diamonds." It was a great event, the arrival of Yégof the madman at the commencement of winter: some rejoiced over it, hoping to keep him and make him relate his glory and fortunes in the inns; others, and especially the women, were filled with a sort of vague uneasiness, for madmen, as all know, have ideas from another world: they know the past and the future—they are inspired by God: the only thing is to know how to understand them—their words bearing always two meanings: one for the ordinary run of people, the other for more refined and delicate souls, and the wise. This madman besides, more than another, had truly some sublime and extraordinary thoughts. None knew from whence he came, nor where he went, nor what he wanted; for Yégof wandered about the country like some troubled spirit. He spoke of extinct races, and pretended that he was Emperor of Australasia, of Polynesia, and of other lands besides. Great books could have been written on his palaces, castles, and strongholds—of which he knew the number, the situation, the architecture—and whose beauty, riches, and grandeur, he would celebrate in a simple and modest manner. He spoke of his stables, of his hunts, of his crown-officers, ministers, counsellors, of the heads of his provinces; he never made any mistakes as to their names or different merits; but he bitterly bewailed having been dethroned by the accursed race: and the old midwife, Sapience Coquelin, every time that she heard him groan over this subject, would cry bitterly, and others also did the same. Then he would raise his arms to heaven and cry out,—"O women, women! remember, remember! The hour approaches—the spirits of darkness flee! the old race—the masters of your masters—advance like the waves of the sea!"

And every spring he was in the habit of making a survey of all the old owls' nests, the ancient castles, and all the ruins which crown the Vosges in the depths of their forests, at Nideck, Géroldseck, Lutzelbourg, and Turkestein, saying that he was going to visit his territories, talking of re-establishing the past splendor of his states, and of putting all mutinous people into slavery, with the aid of his cousin the "Grand Gôlo."

Jean-Claude Hullin made light of these things, from not having a soul elevated enough to enter into the invisible spheres; but Louise was much troubled by them—above all, when the raven flapped its wings and gave its hoarse cry.

Yégof, then, descended the street, without stopping anywhere; and Louise, all excitement, seeing that he looked toward their little house, said aloud,—"Papa Jean-Claude, I believe he is coming our way."

"It is quite possible," replied Hullin. "The poor devil must be in need of a pair of good lined shoes for the great cold, and if he were to ask me, I should hardly be able to refuse them to him."

"Oh, how kind you are!" said the young girl, embracing him affectionately.

"Yes, yes! thou art flattering me," said he, laughing, "because I do what thou wishest. Who will pay me for my wood and work? It will not be Yégof!"

Louise kissed him again, and Hullin, looking lovingly at her, murmured,—"This payment is worth the other."

Yégof was then about fifteen yards from their door: the tumult still kept increasing; the boys hung on to the tatters of his coat, crying out, "Diamond! Club! Spade!" Suddenly he turned, raised his sceptre, and called out in a dignified though furious manner,—"Go back, accursed race! Go back, deafen me no longer, or I will loose my bloodhounds against you!"

This menace only made the shouts of laughter and hisses redouble; but as at that moment Hullin appeared on the threshold with a long strap in his hand, and distinguishing five or six of the most obstinate among them, he warned them that that evening he would go and pull their ears during their supper—a feat which he had already performed several times with the consent of the parents, the whole band dispersed in great consternation. Then, going toward the madman,—"Enter, Yégof," said the shoemaker, "come and warm thyself by the fire."

"I do not call myself Yégof," replied the unhappy man, looking offended. "I call myself Luitprandt, King of Australasia and Polynesia."

"Yes, yes, I know," said Jean-Claude—"I know! Thou hast already told me all that. But what does it matter that thou callest thyself Yégof, or Luitprandt? come in all the same. It is cold; try to warm thyself."

"I come in," replied the madman; "but it is for a much more serious affair: it is for a state affair—to form an indissoluble alliance between the Germans and the Triboques."

"Well, we will talk of that."

Yégof, stooping under the door, entered as though in a reverie, and saluted Louise by bowing and lowering his sceptre; but the raven would not come in. Opening his great wings, he made a circuit around the house, and came and fastened himself onto the window-panes to break them.

"Hans," shouted the madman, "take care! I am coming!"

But the bird did not detach its sharp claws from the casement, and never ceased fluttering its great wings so long as its master remained in the cottage. Louise did not take her eyes off it: she was afraid. As for Yégof, he sat down in the old leathern armchair behind the stove, his legs stretched out as though on a throne; and gazing around him in a triumphant manner, he cried out,—"I come direct from Jérome, to conclude an alliance with thee, Hullin. Thou art not ignorant that I have deigned to cast my eyes on thy daughter, and I come to ask her of thee in marriage."

At this proposition Louise blushed to the roots of her hair, and Hullin burst into a loud laugh.

"Thou laughest!" cried the madman, in a hollow voice. "Well! thou art wrong to laugh. This alliance may alone save thee from the impending ruin of thyself, thy house, and all thy belongings. At this moment my armies are advancing. They are countless—they cover the earth. What can you do against me? You will be vanquished, annihilated, or reduced to slavery, as you have already been for centuries: for I, Luitprandt, King of Australasia and of Polynesia—I have decided that everything shall be as it once was. Remember!"—here the madman raised his finger solemnly—"remember what has passed! You have been beaten! And we, the old northern races—we have put our yokes upon you. We have burdened you with the largest stones for building our strong castles and our subterraneous prisons; we have harnessed you to our ploughs; you have been before us as the straw before the hurricane. Remember, remember, Triboque, and tremble!"

"I remember very well," said Hullin, still laughing; "but we had our revenge. Thou knowest?"

"Yes, yes," interrupted Yégof, frowning; "but that time has gone by. My warriors are more numerous than the leaves in the forests; and your blood flows like the water of the brooks. Thou, I know thee—I knew thee a thousand years ago!"

"Bah!" said Hullin.

"Yes, it was this hand—dost thou hear?—this hand that has vanquished thee, when, for the first time, we entered your forests. It has made thy head bow beneath the yoke—it will make it bend again! Because you are brave, you believe yourselves masters of this country and of all France forever. Well, you are wrong! We have spoiled you, and we will spoil you again. We will restore Alsace and Lorraine to Germany, Brittany and Normandy to the men from the North, with Flanders and the South to Spain. We will make France into a little kingdom around Paris—a very little kingdom—with a descendant of the ancient race at your head. And you will no longer agitate yourselves—you will be very tranquil. Ha, ha, ha!" Yégof began to laugh.

Hullin, who had no knowledge of history, was astonished that he should know so many names.

"Bah! stop that, Yégof," said he; "and come, take a little soup to warm thy inside."

"I do not ask thee for soup; I ask thee for this girl in marriage—the most beautiful on my estates. Give her to me willingly, and I raise thee to the steps of my throne: else my armies shall take her by force, and thou shalt not have the merit of giving her to me."

While thus speaking, the unhappy creature regarded Louise with an air of profound admiration.

"How beautiful she is! I destine her to the greatest honors. Rejoice, young girl, rejoice! Thou shalt be queen of Australasia."

"Listen, Yégof," said Hullin. "I am very much flattered by thy demand: it shows that thou canst appreciate beauty. It is well. But my daughter is already affianced to Gaspard Lefèvre."

"And I," said the madman, greatly irritated—"I will not hear of such a thing!" Then rising up,—"Hullin," said he, in solemn tones, "it is my first demand. I will renew it yet twice again—dost thou hear—twice! And if thou wilt persist in thy obstinacy—misfortune, misfortune on thee and thy race!"

"What! thou wilt not take any soup?"

"No, no! I will accept nothing from thee so long as thou hast not consented. Nothing, nothing!" And then marching toward the door, much to the satisfaction of Louise, who was intent on the raven, fluttering its wings against the window-panes, he said, raising his sceptre,—"Twice again!" and departed.

Hullin went off into a shout of laughter. "Poor devil!" he exclaimed. "In spite of himself, his nose turned toward the porringer. He has nothing in his inside—his teeth chatter with hunger. Well! his madness is stronger than either cold or hunger."

"Oh, how he frightened me!" said Louise.

"Come, come, my child, calm thyself. He is gone. He thinks thou art pretty, fool though he is; do not let that terrify thee."

But although the madman had left, Louise still trembled, and felt herself blushing when she thought of how he had looked at her.

Yégof had taken the road to Valtin. He could still be seen, his raven on his shoulder, walking slowly along and making curious gestures, although no one was near him. The night was drawing on, and soon the tall figure of "The King of Diamonds" disappeared in the gray shadows of the winter twilight.

In the evening of that same day, after their supper, Louise, having taken her spinning-wheel, was gone for a little diversion to the Mother Rochart's where all the good women and young girls of the neighborhood used to assemble till near midnight. They spent their time in relating old legends, talking of the rain, of the weather, of marriages, baptisms, of the departure or return of the conscripts, and what not, that enabled them to pass the hours agreeably.

Hullin remained alone before his little copper lamp, nailing the shoes of the old wood-cutter. He no longer thought of the madman Yégof. His hammer rose and fell, driving the great nails into the thick wooden shoes quite mechanically, by force of habit. In the meantime thousands of ideas came into his head; he was thoughtful without knowing why. Now it was Gaspard, who gave no signs of being alive; then it was the campaign, which was being indefinitely prolonged. The lamp threw its yellowish light around the smoky little room. Outside, not a sound. The fire began to die away. Jean-Claude rose to put on a fagot, then sat down again, muttering,—"Bah! this cannot last; we shall receive a letter one of these days."

The old clock began to strike nine; and as Hullin was recommencing his work, the door opened and Catherine Lefèvre, the mistress of Bois-de-Chênes, appeared on the threshold, to the great stupefaction of the shoemaker, for it was not her custom to arrive at such a time.

Catherine Lefèvre might have been sixty years old, but she was as upright and strong as at thirty. Her clear gray eyes and beaked nose resembled those of a bird of prey; the corners of her mouth turned down, and made her look somewhat gloomy and sad; two or three locks of gray hair fell over her forehead; a brown striped hood reached from her head, over her shoulders and down to her elbows. Her physiognomy announced a steadfast, tenacious character, with something indescribably grand and mournful about it, which inspired both respect and fear.

"Can it be you, Catherine?" said Hullin, in astonishment.

"Yes, it is I," replied the old dame, calmly. "I am come to talk with you, Jean-Claude.... Louise is away?"

"She has gone for a little amusement to Madeleine Rochart's."

"It is well."

Then Catherine pushed back her hood from her head, and sat down at the end of the bench. Hullin looked fixedly at her: he perceived something extraordinary and mysterious about her which fascinated him.

"What has happened, then?" said he, putting down his hammer.

Instead of answering this question, she turned toward the door, and seemed to be listening; then hearing no sound, her serious expression came back.

"Yégof the madman spent last night at the farm," said she.

"He came to see me this afternoon," rejoined Hullin, without attaching any importance to this fact, which was totally indifferent to him.

"Yes," replied the old dame, in a low voice, "he spent the night with us; and yesterday evening, about this time, in the kitchen, before us all, this madman related terrible things!"

Then she relapsed into silence, and the corners of her mouth seemed to turn down more than ever.

"Terrible things!" murmured the shoemaker, excessively astonished: for he had never seen Catherine Lefèvre in such a condition before. "But what then? say, what?"

"Dreams I have had!"

"Dreams? You certainly want to make fun of me!"

"No!"

Then, after a short pause, she slowly continued—"Yesterday evening, all our people were assembled in the kitchen around the large fireplace after supper; the table still remained covered with empty dishes, plates, and spoons. Yégof had partaken of it with us, and had amused us with the history of his treasures, castles, and provinces. It might have been toward nine o'clock: the madman was sitting at one end of the blazing fire; old Duchêne, my ploughboy, was mending Bruno's saddle; the herdsman, Robin, was plaiting a basket; Annette arranged her pans on the shelves: and I had brought my wheel nearer the fire to finish spinning a distaff-ful before going to bed. Out of doors, the dogs were barking at the moon; the cold was very great. We were all there, talking of the coming winter. Duchêne said it would be very severe, for he had seen several flocks of wild-geese. And Yégof's raven, on the edge of the mantel-piece, its head buried in its raffled feathers, seemed to sleep; but now and then it would elongate its neck and watch us, listen a moment and then cover itself again in its plumes."

She remained silent a moment, as though to collect her ideas; her eyelids drooped, her great beaked nose seemed to bend down on to her lips, and a strange pallor came over her face.

"What the devil is coming next?" thought Hullin.

The old woman continued: "Yégof near the fire, with his tin crown, and his short stick on his knees, was dreaming of something. He looked at the great black chimney, the stone mantel-piece, which is carved with different figures and trees, and the smoke which went up in great clouds around the sides of bacon: when suddenly he struck with the end of his stick on to the tiles and called out, as though in a dream—'Yes, yes, I have seen that long ago—long ago!' And as we all looked at him speechless—'In those times,' he went on to say, 'the pine-forests were forests of oak. The Nideck, the Dagsberg, Falkenstein, Géroldseck, all those old ruined castles did not exist. In those times the bison could be hunted in the depths of the woods, the salmon caught in the Sarre, and you, the fair men, were buried in snow six months of the year. You lived on milk and cheese, for you had many flocks and herds on the Hengst, the Schneeberg, the Grosmann, the Donon. In the summer you hunted: you came down to the Rhine, the Moselle, the Meuse. I can recall it all!'

"And wonderful to relate, Jean-Claude, as the madman spoke, I seemed to see also these countries of years gone by, and to remember them as I should a dream. I had let fall my distaff, and Duchêne, Robin, Jeanne—in fact, everybody—listened. 'Yes, it was long ago,' he continued. 'In those days you were already building these great chimneys; and all around, at a distance of two or three hundred yards, you planted palisades fifteen feet high, and with the points hardened by the fire. And inside them you kept your big dogs with their hanging cheeks, who barked day and night.'

"We could see what he said, Jean-Claude; we could see it all. But he paid no heed to us: he regarded the figures on the chimney-piece with his mouth open; but, in an instant, having stooped his head and seeing how attentive we all were, he laughed with a wild, mad laughter, and cried out:—'In those days you believed yourselves the lords of the country, O fair men, with your blue eyes and white skins, fed on milk and cheese, and only tasting blood in the autumn, at the great hunts: you believed yourselves the masters of the plains and mountains, when we, the red men, with the green eyes, out of the sea—we who drank always blood and only liked battles—one fine morning we arrived with our axes and spears, and ascended the Sarre under the shadows of the old oaks. Ah! it was a cruel war, which lasted weeks and months. And the old woman—there—' said he, pointing at me, with a singular smile, 'the Margareth of the clan of Kilberix, that old woman with her beaked nose, in her palisades, in the midst of her dogs and warriors—she fought like a wolf. But when five moons had passed, hunger arrived. The doors of the palisades opened for flight, and we, in ambush in the stream—we massacred all!—all—except the children and the beautiful young girls. The old woman, alone, defended herself to the last with her teeth and nails; and I, Luitprandt, clove her head in two; and I took her father, the aged man and blind, to chain him at the door of my castle like a dog!'

"Then, Hullin," continued the old woman, "the madman began to chant a long song—the lamentation of the old man chained to his doorway. Wait till I can recall it, Jean-Claude. It was mournful—mournful as a Miserere. No, I cannot remember it; but I seem still to hear it. It made our blood curdle; and, as he laughed without ceasing, at last all our servants gave a terrible cry, rage seized them. Duchêne sprang on the madman to strangle him; but he, with more strength than one could suppose he possessed, threw him back, and raising his stick furiously, said to us:—'On your knees, slaves—on your knees! My armies are advancing! Do you hear? The earth trembles with them. These castles, the Nideck, the Haut-Barr, the Dagsberg, the Turkestein, you shall build them up again! On your knees!'

"I never saw a more fearful face than Yégof's at that moment; but, seeing for the second time my servants rising against him, I was obliged to defend him myself. 'It is a madman,' I said to them. 'Are you not ashamed to believe in the words of a madman?' They stopped on my account; but I could not close my eyes that night. The words of that wretched man kept recurring to me. I seemed to hear the chant of the old prisoner, the barking of our dogs, and the sounds of battle. For years I have never felt so uneasy. That is why I came to see you, Jean-Claude. What do you think of it?"

"I?" exclaimed the shoemaker, in whose ruddy face both irony and pity were visible. "If I did not know you so well, Catherine, I should say you were deranged:—you, Duchêne, Robin, and the rest of you. All that has about the same effect on me as one of Geneviève de Brabant's tales—made up to terrify little children, and which shows us how foolish our ancestors were."

"You do not comprehend these things," said she, in a calm, grave voice; "you have never had any of those ideas."

"Then you believe all that Yégof has said to you?"

"Yes, I believe it."

"What, you, Catherine?—you, a sensible woman? If it were the mother of Rochart I should say nothing; but you!"

He rose as though annoyed, took off his apron, shrugged his shoulders, then sat down again quickly, and called out:—"This madman, do you know what he is? I will tell you. He is most assuredly one of those German school-masters who stuff their brains with 'Old Mother Goose' tales, and then gravely relate them to others. By dint of studying, dreaming, ruminating, their wits get out of order; they have visions, many-sided ideas, and take their dreams for realities. I have always looked upon Yégof as one of those poor wretches. He knows lots of names, he speaks of Brittany and Australasia, of Polynesia and the Nideck, and then of Géroldseck, of the Turkestein, of the Rhine—in fact of everything at hazard; and it ends by having the appearance of something when it is nothing. In ordinary times you would think as I do, Catherine; but you are troubled at not receiving any tidings from Gaspard. These rumors of war and of invasion that are going about torment and unsettle you. You cannot sleep; and what a poor madman says, you regard as Bible truths."

"No, Hullin; it is not that. If you yourself had heard Yégof——"

"Get along!" exclaimed the good old fellow. "If I had, I should have laughed at him as I did just now. Do you know that he came to ask Louise of me in marriage, to make her queen of Australasia?"

Catherine Lefèvre could not restrain a smile; but, regaining almost at once her serious expression—"All your reasonings, Jean-Claude," said she, "cannot convince me; but, I confess it, the silence of Gasper frightens me. I know my son: he would certainly have written to me. Why have his letters never reached me? The war is going on badly, Hullin—we have all the world against us. They don't want our revolution—you know it as well as I do. So long as we were masters, and won victory after victory, they looked kindly on us; but since our Russian misfortunes, things wear a bad aspect."

"Là, Là, Catherine, how you get carried away. You see everything gloomily."

"Yes, I see everything gloomily, and I am right. What makes me so uneasy is, that we never get any news from the outer world; we live here as in a savage country: one knows of nothing that goes on. The Austrians and the Cossacks could be upon us at any time, and we should be taken by surprise."

Hullin observed the old dame, whose expression was very animated; and even he began to be influenced by the same fears.

"Listen, Catherine," said he, suddenly. "When you speak in a reasonable manner, it is not I who would say anything against it. All you now tell me is possible. I do not believe in it; but one might as well make sure. I had intended to go to Phalsbourg in a week, to buy sheepskins for trimming some shoes: I will go to-morrow. At Phalsbourg, a garrison and post town, there must be some reliable news. Will you believe those I shall bring you on my return from that place?"

"Yes."

"Good; it is then arranged. I shall leave to-morrow early. There are five leagues in all. I shall return about six o'clock. You will see, Catherine, that all your dismal ideas have no sense in them."

"I hope so," she replied, rising. "I hope so. You have somewhat reassured me, Hullin. Now I will go to the farm, and may I sleep better than I did last night. Good-night, Jean-Claude."

The next day at dawn, Hullin, wearing his blue cloth Sunday breeches, his large brown velvet jacket and red waistcoat with brass buttons, and a broad beaver mountaineer's hat turned up like a cockade above his ruddy face—started on his way to Phalsbourg, a stout stick in his hand.

Phalsbourg is a small fortress, half-way on the imperial road from Strasbourg to Paris; it dominates Saverne, the defiles of Haut-Barr, Roche-Platte, Bonne-Fontaine, and of the Graufthâl. Its bastions, outposts, and demilunes are cut out in zig-zags on a rocky plain: from afar, the walls look as though they might be cleared at a jump; but on coming closer one perceives the moat, a hundred feet wide, thirty deep, and the dark ramparts hewn in the face of the rock. That makes one stop suddenly. Besides, with the exception of the church, the town-hall, the two gateways of France and Germany, in shape of mitres, and the peaks of the two powder-magazines, all the rest is hidden behind the fortifications. Such is Phalsbourg, which is not without a certain imposing effect, especially when one crosses its bridges and piers, under its thick gates, garnished with iron-spiked portcullis. In the interior, the houses are distributed in regular quarters; they are low, in straight lines, built of freestone: everything bears a military aspect.

Hullin, owing to his robust constitution and jovial disposition, never had any fears for the future, and considered all rumors of retreat, rout, and invasion, which circulated in the country, as so many lies propagated by dishonest individuals; so that one may judge of his stupefaction when, on leaving the mountains and from the outskirts of the woods, he saw the whole surroundings of the town laid as bare as a pontoon: not a garden, not an orchard, not a promenade, or a tree, or even a shrub—all was destroyed within cannon-range. A few poor creatures were picking up the last remnants of their little houses, and carrying them into the town. Nothing was to be seen on the horizon but the line of ramparts standing out clearly above the hidden roads. It had the effect of a thunder-bolt on Jean-Claude.

For some moments he could neither articulate a word nor make a step forward.

"Oh, ho!" said he, at last, "this is bad—this is very bad. They expect the enemy."

Then his warlike instincts prevailed; a dark flush came over his brown cheeks. "It is those rascally Austrians, Prussians, and Russians, and all the other wretches picked up out of the dregs of Europe, who are the cause of this," cried he, waving his stick. "But beware! we will make them pay for the damages!"

He was possessed with one of those white rages such as honest people feel when they are driven to extremities. Woe to him who annoyed Hullin just then!

Twenty minutes later he entered the town, at the rear of a long file of carriages, each harnessed to five or six horses, pulling, with much trouble, enormous trunks of trees, destined to construct block-houses on the place-d'armes. Among the conductors, the peasants, and neighing, stamping horses, marched gravely a mounted gendarme—Father Kels—who did not seem to hear anything, and said, in a rough voice, "Courage, courage, my friends! We will make two more journeys before evening. You will have deserved well of your country!"

Jean-Claude crossed the bridge.

A new spectacle opened before him in the town. There reigned the ardor of defence: all the doors were open; men, women, and children came and ran, helping to transport the powder and projectiles. They stopped in groups of three, four, six, to make themselves acquainted with the news.

"Hé neighbor!"

"What then?"

"A courier has just arrived in great speed. He entered by the French gate."

"Then he has come to announce the National Guard from Nancy."

"Or, perhaps, a convoy from Metz."

"You are right. We want sixteen-pounders, and shot also. The stoves are to be broken up to make some."

A few worthy tradespeople in their shirt-sleeves, standing on tables along the pavement, were busying themselves with barricading their windows with large pieces of wood and mattresses; others rolled up to their doors tubs of water. This enthusiasm reanimated Hullin.

"Excellent!" said he; "everybody is making holiday here. The allies will be well received."

In front of the College, the squeaky voice of the Sergeant-de-ville Harmentier was proclaiming:—

"Let it be known that the casemates are to be opened: therefore everybody may take a mattress there, and two blankets each. And the commissaries of this place are going to commence their rounds of inspection, to ascertain that each inhabitant possesses food for three months in advance, which he must certify.—This day, 20th December, 1813.—JEAN PIERRE MEUNIER, Governor."

All this Hullin saw and heard in less than a minute, for the whole town was in the greatest excitement. Strange, serious, and comic scenes succeeded each other without interruption.

Near the narrow street leading to the Arsenal, a few National Guards were drawing a twenty-four pounder. These honest fellows had a very steep ascent to climb; they could do no more. "Ho! all together! Mille tonnerres! Once again! Forward!" They all shouted at once, pushing the wheels, and the great cannon, stretching out its long neck over its immense carriage, above their heads, rolled slowly along, making the pavement tremble.

Hullin, quite rejoiced, was no longer the same man. His soldier-like instincts, the remembrance of the bivouac, of the marches, of the firing, and of the battles—all returned. His eyes sparkled, his heart beat faster, and already thoughts of defence, of entrenchments, of death-struggles came and went in his head.

"Faith!" said he, "all goes well! I have made enough shoes in my life, and since the occasion to take up the musket presents itself, well, so much the better: we will show the Prussians and Austrians that we have not forgotten to charge at the double."

Thus reasoned the good man, carried away by his warlike instincts; but his joy did not last long.

Before the church, on the place-d'armes, were standing fifteen or twenty carts, full of wounded, arrived from Leipzig and Hanau. These unhappy creatures, pale, ghastly, heavy-eyed, some whose limbs were already amputated, others with their wounds still untouched, tranquilly awaited death. Near them, a few worn-out jades were eating their meagre allowance, while the conductors, poor wretches, who had been brought into requisition in Alsace, wrapped in their old mantles, slept notwithstanding the cold—their great hats turned down over their faces and their arms folded—on the steps of the church. One shuddered to see these sad groups of men, with their gray hoods, heaped up on the bloody straw—one carrying his broken arm on his knees; another with his head bandaged in an old handkerchief; a third, already dead, being used as a seat for the living, his black hands hanging down the ladder. Hullin, in front of this mournful spectacle, stopped rooted to the ground. He could not lift his eyes from it. Great human suffering has this strange power of fascination over us: we look to see men perish, how they regard death: the best among us are not exempt from this frightful curiosity. It seems as though eternity is going to deliver up its secret!

There, then, near the shafts of the first cart, to the right of the file, were crouched two carbineers in little sky-blue vests, veritable giants, whose powerful natures gave way under the clutch of pain: like two caryatides crushed by the weight of some heavy mass. One, with great red mustaches and ashy cheeks, looked at you out of his sunken eyes, as though from the depths of some fearful nightmare; the other, bent double, with blue hands, and shoulder torn by shot, sank more and more; then would raise himself with a jerk, talking softly as though dreaming. Behind lay stretched, two and two, some infantry soldiers, the greater number struck by ball, with a leg or an arm broken. They seemed to support their fate with more firmness than the giants. These poor creatures said nothing: a few only, the youngest, furiously demanded water and bread; and in the next cart, a plaintive voice—the voice of a conscript—called, "My mother! my mother!" while the older men smiled gloomily, as though to say: "Yes, yes, she will come, thy mother!" Perhaps they did not think of anything all the time.

Now and then a shudder would pass along the whole of them. Then several wounded could be seen half lifting themselves, with deep groans, and falling back as if death had gone its rounds at that moment.

And again everything relapsed into silence. While Hullin was watching, and feeling sick to his heart's core, a shopkeeper in the vicinity, Sôme the baker, came out of his house carrying a large basin of soup. Then you should have seen all these spectres move, their eyes sparkle, their nostrils dilate; they seemed born again. The unhappy fellows were dying of hunger!

Good Father Sôme, with tears in his eyes, approached, saying, "I am coming, my children. A little patience! It is I, you know me!"

But hardly was he near the first cart, when the great carbineer with the ashy cheeks, reviving, plunged his arm up to the elbow in the boiling basin, seized the meat, and hid it under his vest. It was done with the rapidity of lightning. Savage yells arose on all sides: those men, if they had had strength to move, would have devoured their comrade. He, his arms pressed tightly to his chest, the teeth on has prey, and glaring round him, appeared to hear nothing. At these cries an old soldier, a sergeant, rushed out of the nearest inn. He was an old hand; he understood at once what it was about, and, without useless reflections, he tore away the meat from the wild beast, saying to him, "Thou dost not deserve any! It must be divided into parts. We will cut ten rations!"

"We are only eight!" said one of the wounded, very calm to all appearance, but with eyes gleaming out of their bronze mask.

"How, eight?"

"You can see, sergeant, that those two are dying fast: it would be so much food lost!"

The old sergeant looked.

"Eight," said he; "eight rations!"

Hullin could bear it no longer. He went over to the innkeeper Wittmann's opposite, as white as death; Wittmann was also a fur and leather merchant. Seeing him enter, "Hé! is it you, Master Jean-Claude?" he exclaimed. "You arrive sooner than usual; I did not expect you till next week." Then seeing how he staggered—"But say, you are ill?"

"I have just seen the wounded."

"Ah, yes! the first time, it shocks you; but if you had seen fifteen thousand pass, as we have, you would not think anything more about it."

"A glass of wine, quick?" said Hullin, who felt badly. "Oh, mankind, mankind! And to think that we are brothers!"

"Yes, brothers until it touches your purse," replied Wittmann. "Come, drink! that will set you right."

"And you have seen fifteen thousand go by?" rejoined the shoemaker.

"At the least, for two months, without speaking of those who have remained in Alsace and the other side of the Rhine; for, you comprehend, they cannot find carts enough for all, and then many are not worth the trouble of being carried away."

"Yes, I comprehend! But why are they there, those poor creatures? Why do they not go into the hospital?"

"The hospital! What is one hospital, ten hospitals, for fifty thousand wounded? Every hospital, from Mayence and Coblentz as far as Phalsbourg, is crowded. And, besides, that terrible fever, typhus, you see, Hullin, kills more than the bullet. All the villages of the plain twenty leagues round are infected with it; they die everywhere like flies. Luckily the town has been in a state of siege these three days; the gates will be closed, and no more will enter. I have lost, for my part, my Uncle Christian and my Aunt Lisbeth, as healthy, solid people as you and I, Master Jean-Claude. At last the cold has arrived; last night there was a white frost."

"And the wounded remained on the pavements all night?"

"No, they came from Saverne this morning; in an hour or two, when the horses are rested, they will leave for Sarrebourg."

At that moment, the old sergeant, who had re-established order in the carts, came in rubbing his hands.

"Hé! hé!" said he, "it freshens, Papa Wittmann. You did well to light the fire in the stove. A little glass of cognac to drive away the fog. Hum! hum!"

His small half-closed eyes, his beaked nose, the cheek-bones being separated from it by two flourishing wrinkles, which were lost to sight in a long reddish imperial—everything looked gay in his face, and told of a jovial, kind disposition. It was a regular military face, scorched, burnt by the open air, full of frankness, but also of a cheery slyness; his great shako, his blue-gray cloak, the shoulder-belt, the epaulette, seemed to partake of his individuality. One could not have represented him without them. He walked up and down the room, continuing to rub his hands, while Wittmann poured him a glass of brandy. Hullin, seated near the window, had at once noticed the number of his regiment—6th Light Infantry. Gaspard, the son of Madame Lefèvre, served in this regiment. Jean-Claude could now obtain some tidings of the lover of Louise; but, as he was going to speak, his heart beat loud. If Gaspard was dead; if he had perished like so many others!

The worthy shoemaker felt nearly suffocated; he kept silent. "Better to know nothing," thought he. However, a few minutes later, he could do so no longer. "Sergeant," said he, in a hoarse voice, "you are in the 6th Light Infantry?"

"Yes, my citizen," said the other, turning round in the middle of the room.

"Do you know one called Gaspard Lefèvre?"

"Gaspard Lefèvre, of the 2d division of the 1st? Parbleu, if I know him! It is I who taught him his drill. A brave soldier! hardened against fatigue. If we had a hundred thousand of that stamp——"

"Then he lives? he is well?"

"Yes, citizen. Eight days ago I left the regiment at Fredericsthal to escort this convoy of wounded. You understand, it is hot there—one cannot answer for anything. From one moment to the other, each of us may have his business settled for him. But eight days ago, at Fredericsthal—the 15th December—Gaspard Lefèvre still answered to the roll-call."

Jean-Claude breathed. "But then, sergeant, have the goodness to tell me why Gaspard has not written to his village for two months?"

The old soldier smiled, and blinked his little eyes. "Ah! now, citizen, do you then believe that one has nothing else to do on the march but to write?"

"No. I have served; I was in the campaigns of Sambre-et-Meuse, of Egypt and Italy, but that did not prevent me from giving some news of myself."

"One instant, comrade," interrupted the sergeant. "I have passed through Egypt and Italy also; the campaign we are finishing is altogether different."

"It has then been very severe?"

"Severe! one must have one's soul driven into every part of one's members, so as not to leave one's bones there. All was against us: sickness, traitors, peasants, townsfolk, our allies—in fact all! From our company, which was complete when we quitted Phalsbourg, the 21st of last January, only thirty-four men remain. I believe Gaspard Lefèvre is the only conscript left. Those poor conscripts! they fought well; but they were not accustomed to endure hardships: they melted like butter in an oven." So saying, the old sergeant approached the counter and drank his glass off at one draught. "To your health, my citizen. Are you perchance the father of Gaspard?"

"No, I am a relation."

"Well, you can pride yourselves on being stoutly built in your family. What a man at twenty! He has gone through everything—he has, while the others fell away in dozens."

"But," rejoined Hullin, after an instant's silence, "I cannot see anything so very different in this last campaign; for we also had sickness and traitors."

"Anything different!" exclaimed the sergeant. "Everything was different! Formerly, if you have gone through the war in Germany, you ought to remember that, after one or two victories, it was over: the people received you well; one drank the little white wines, and ate sauerkraut and ham with the townsfolk; one danced with the buxom wives. The husbands and grandpapas laughed heartily, and when the regiment left, everybody cried. But this time, after Lutzen and Bautzen, instead of feeling kindly, the people regarded us with diabolical faces; we could get nothing out of them but by force; one could have fancied one's self in Spain or Vendée. I do not know what stuff they had in their heads against us. Better had we only been French, had we not had Saxons and other allies, who only awaited the moment to spring at our throats: we should then have pulled through all the same, one against five! But the allies—don't talk to me of the allies! Why, at Leipzig, the 18th of October last, in the hottest part of the battle, our allies turned against us and shot at us from behind; those were our good friends the Saxons. A week later, our former friends the Bavarians came and threw themselves across our retreat: we had to pass over them at Hanau. The day after, near Frankfort, another column of good friends presented themselves, and we had to crush them. The more one kills, the more they come! Here we are now this side of the Rhine. Well, there are decidedly more of these good friends marching from Moscow. Ah! if we could have foreseen it after Austerlitz, Jena, Friedland, Wagram!"

Hullin had become very thoughtful. "And now how do we stand, sergeant?"

"We have had to repass the Rhine, and all our strongholds on the other side are blockaded. The 10th of November last the Prince of Neufchâtel reviewed the regiment at Bleckheim. The 3d battalion had been amalgamated with the 2d, and the 'cadre' received orders to be in readiness to leave for the depot. Cadres are not wanting, but men. As for twenty years we have been bled on all sides, it is not astonishing. All Europe is down upon us. The Emperor is at Paris; he is laying down a plan of the campaign. If we may only have breathing time till the spring——"

Just then Wittmann, who was standing by the window, said,—"Here is the governor come from inspecting the clearings around the town."

It was the commandant, Jean-Pierre Meunier, wearing a three-cornered hat, and a tricolor scarf around his waist, who crossed over the square.

"Ah," said the sergeant, "I must get him to sign my papers. Pardon, citizen; I must leave you."

"Do so, sergeant; and thank you. If you meet Gaspard, tell him that Jean-Claude Hullin embraces him, and that they expect tidings from him in the village."

"Good—good. I will not fail to do so."

The sergeant went out, and Hullin finished his wine in a reverie.

"Father Wittmann," said he, after a pause, "what of my parcel?"

"It is ready, Master Jean-Claude." Then, looking into the kitchen, "Grédel! Grédel! bring Hullin's parcel."

A little woman appeared, and put down on the table a roll of sheepskins. Jean-Claude passed his stick through it, and lifted it over his shoulder.

"What, you are going to leave us so soon?"

"Yes, Wittmann. The days are short, and the roads difficult through the forests after six o'clock. I must get back early."

"Then a safe journey to you, Master Jean-Claude."

Hullin left, and crossed the square, turning away his face from the convoy, which still remained before the church.

The innkeeper from his window watched him hurrying away, and thought to himself, "How white he looked on entering; he could hardly keep upright. It is queer that such a sturdy man, and an old soldier too, should not have energy enough for a cat. As for me, I would see fifty regiments go by on those carts without minding it any more than I did my first pipe."

While Hullin was learning the disaster of our armies, and was walking slowly, his head bent, and an anxious expression on his face, toward the village of Charmes, everything went on as usual at the farm of Bois-de-Chênes. No one thought of Yégof's wonderful stories, or of the war: old Duchêne led his oxen to their drinking-place, the herdsman Robin turned over their litter; Annette and Jeanne skimmed their curdled milk. Only Catherine Lefèvre was silent and gloomy—thinking of days gone by—all the while superintending with an impassible face the occupations of her domestics. She was too old and too serious to forget from one day to another what had so much troubled her. When night came on, after the evening's repast, she entered the great room, where her servants could hear her drawing the large register-book from the closet and putting it on the table, to sum up her accounts, as she was in the habit of doing.

They soon began to load the cart with corn, vegetables, and poultry: for the next day there was a market at Sarrebourg, and Duchêne had to start early.

Picture to yourself the great kitchen, and all these worthy folks hurrying to finish their work before going to rest: the black kettle, full of beetroot and potatoes destined for the cattle, boiling on an immense pinewood fire; the plates, dishes, and soup-tureens shining like suns on the shelves; the bunches of garlic and of reddish-brown onions hung up in rows to the beams of the ceiling, among the hams and flitches of bacon; Jeannie, in her blue cap and little red petticoat, stirring up the contents of the kettle with a big wooden spoon; the wicker cages, with the cackling fowls and great cock, who pushed his head through the bars and looked at the flames with a wondering eye and raised crest; the bull-dog Michel, with his flat head and hanging jowl, in search of some forgotten dish; Dubourg coming down the creaking staircase to the left, his back bent with a sack on his shoulder; while outside, in the dark night, old Duchêne, upright on the cart, lifted his lantern and called out, "That makes the fifteenth, Dubourg; two more." One could see also, hanging against the wall, an old hare, brought by the hunter Heinrich to be sold at the market, and a fine grouse, with its purple and green plumage, dimmed eye, and a drop of blood at the end of its beak.

It was about half-past seven when the sound of footsteps was heard at the entrance to the yard. The bull-dog went toward the door growling. He listened, sniffed the night air, then went back quietly, and began licking his dish again.

"It is some one belonging to the farm," said Annette. "Michel does not move."

Nearly at the same time, old Duchêne from outside called,—"Good-night, Master Jean-Claude. Is it you?"

"Yes. I come from Phalsbourg; and I am going to rest myself a minute before going down to the village. Is Catherine here?"

And then the good man came forward to the light, his hat pushed off his face, and his roll of sheepskins on his back.

"Good-night, my children," said he; "good-night! Always at work!"

"Yes, Monsieur Hullin, as you see," replied Jeanne, laughing. "If one had nothing to do, life would be very wearisome."

"True, my pretty girl, true. It is only work which gives you your roses and brilliant eyes."

Jeanne was going to answer, when the door of the great room opened, and Catherine Lefèvre advanced, looking piercingly at Hullin, as though to guess beforehand what news he brought.

"Well, Jean-Claude, you have returned."

"Yes, Catherine; with good tidings and bad."

They entered the large room—a high and spacious apartment wainscoted with wood to the ceiling, with its oak closets and their shining clasps, its iron stove opening into the kitchen, its old clock counting the seconds in its walnut-wood case, and the leathern arm-chair, worn and used by ten generations of aged men. Jean-Claude never went into this room without its bringing back to his remembrance Catherine's grandfather, whom he seemed still to see, with his white head, sitting behind the oven in the dark.

"Well?" demanded the old dame, offering a chair to the old shoemaker, who was just putting his pack down on the table.

"Well, from Gaspard the tidings are good; the boy is in good health. He has had hardships. All the better: it will be the making of him. But for the rest, Catherine, it is bad. The war! the war!"

He shook his head, and the old woman, her lips pressed, sat down facing him, upright in the armchair, her eyes attentively fastened on him.

"So things look badly—decidedly—we shall have the war among us?"

"Yes, Catherine, from day to day we may expect to see the allies in our mountains."

"I thought so. I was sure of it; but speak, Jean-Claude."

Hullin, then, his elbows on his knees, his red ears between his hands, and lowering his voice, began to relate all he had seen: the clearing of everything around the town, the placing of batteries on the ramparts, the proclamation of the state of siege, the cart-loads of wounded on the great square, his meeting with the old sergeant at Wittmann's, and the story of the campaign. From time to time he paused, and the old mistress of the farm blinked her eyes slowly, as though to impress more deeply the various circumstances on her mind. When Jean-Claude told about the wounded, the good woman murmured softly—"Gaspard has then escaped it all!"

Then, at the end of this mournful tale, there was a long silence, and both looked at each other without pronouncing a word.

How many reflections, how many bitter feelings filled their souls!

After some seconds, Catherine recovering from these terrible thoughts—"You see, Jean-Claude," said she, in a serious tone. "Yégof was not wrong."

"Certainly, certainly, he was not wrong," replied Hullin; "but what does that prove? A madman, who goes from village to village, who descends into Alsace, and from thence to Lorraine—who wanders from right to left—it would be very astonishing if he saw nothing, and if he did not sometimes tell the truth in his madness. Everything gets muddled in his head, and others believe they understand what he does not understand himself. But what of these wild stories, Catherine? The Austrians are upon us. It only concerns us to know if we shall allow them to pass, or if we shall have courage to defend ourselves."

"To defend ourselves!" cried the old woman, whose white cheeks trembled: "if we shall have courage to defend ourselves! Surely it is not to me that you speak, Hullin. What! are we not worthy of our ancestors? Did they not defend themselves? Were they not exterminated—men, women, and children?"

"Then you are for the defence, Catherine?"

"Yes, yes; so long as there remains to me a bit of skin on my bones. Let them come! The oldest of the women is ready!"

Her masses of gray hair shook on her head, her pale rigid cheeks quivered, and her eyes sent forth lightnings. She was beautiful to see—beautiful, like that old Margareth of whom Yégof had spoken. Hullin held out his hand silently, and gave an enthusiastic smile.

"Excellent," said he—"excellent! We are always the same in this family. I know you, Catherine: you are ready now; but be calm and listen to me. We are going to fight, and in what way?"

"In every way; all are good—axes, scythes, pitchforks."

"No doubt; but the best are muskets and the balls. We have muskets: every mountaineer keeps his above his door; unfortunately powder and balls are scarce."

The old dame became quieter all of a sudden; she pushed her hair back under her cap, and looked anxiously about.

"Yes," she rejoined brusquely; "the powder and balls are wanting, it is true, but we shall have some. Marc Divès, the smuggler, has some. You shall go and see him to-morrow from me. You shall tell him that Catherine Lefèvre will buy all his powder and balls; that she will pay him; that she will sell her cattle, her farm, land, everything—everything—to have some. Do you understand, Hullin?"

"I understand. What you would do, Catherine, is noble."

"Bah! it is noble—it is noble!" replied the old dame. "It is quite simple; I wish to revenge myself. These Austrians—these red men who have already exterminated us—well! I hate them, I detest them, from father to son. There! you will buy powder, and these mad ruffians shall see if we will rebuild their castles."

Hullin then perceived that she still thought of Yégof's tale; but seeing how exasperated she was, and that, besides, her idea contributed to the defence of the country, made no observation on that subject, and said calmly,—"So, Catherine, it is settled; I am to go over to Marc Divès's to-morrow!"

"Yes! you shall buy all his powder and lead. Some one ought also to go the round of the mountain villages, to warn the people of what is coming, and to arrange a signal beforehand for bringing them together in case of attack."

"Do not fear," said Jean-Claude. "I will undertake to charge myself with that."

Both rose and turned toward the door. For about half an hour no sounds were heard in the kitchen; the farm-servants had gone to bed. The old dame put down her lamp on the corner of the hearth, and drew the bolts. Outside the cold was intense, the air still and clear. All the peaks round, and the pine-trees of the Jägerthal, stood out against the sky in dark or light masses. In the distance, far away behind the hill-side, a fox giving chase could be heard yelping in the valley of Blanru.

"Good-night, Hullin," said Catherine.

"Good-night."

Jean-Claude walked quickly away on the heath-covered slopes, and the mistress of the farm, after watching him for a second, shut her door again.

I leave you to imagine the joy of Louise when she learnt that Gaspard was safe and sound. The poor child had hardly been living for two months. Hullin took care not to show her the dark cloud which was coming over the horizon.

Through the night he could hear her prattling in her little room, talking as though congratulating herself, murmuring Gaspard's name, opening her drawers and boxes, without doubt so as to hunt up some relics in them and tell them of her love.

So the linnet drenched in the storm, will, while yet shivering, begin to sing and hop from branch to branch with the first sunbeam.

When Jean-Claude Hullin, in his shirt-sleeves, opened the shutters of his little house the next morning, he saw all the neighboring mountains—the Jägerthal, the Grosmann, the Donon—covered with snow. This first appearance of winter, coming in our sleep, is very striking to us: the old pines, the mossy rocks, adorned only the night before with verdure, and now sparkling with rime, fill our souls with an indefinable sadness. "Another year gone by," one says to one's self; "another hard season to pass before the return of the flowers!" And one hastens to put on the great-coat and to light the fire. Your sombre habitation is filled with a white light, and outside, for the first time, you hear the sparrows—the poor sparrows huddled under the thatch, their feathers ruffled—calling, "No breakfast this morning—no breakfast!"

Hullin drew on his big iron-nailed, double-soled shoes, and over his vest a great thick cloth waistcoat.

He heard Louise walking overhead in the little garret.

"Louise," he cried, "I am going."

"What! you are going away to-day also?"

"Yes, my child: it must be so: my affairs are not yet finished."

Then, having doffed his large hat, he went up the stair, and said, in a low tone: "Thou must not expect me back so soon, my child. I have to make some distant rounds. Do not be uneasy. If any one ask where I am, thou art to reply, 'He is with Cousin Mathias at Saverne.'"

"You will not have breakfast before leaving?"

"No: I have a crust of bread and the small flask of brandy in my pocket. Adieu, my child! Rejoice, and dream of Gaspard."

And, without waiting for fresh questions, he took his stick and left the house, going in the direction of the hill of Bouleaux to the left of the village. In a quarter of an hour he had passed it by, and reached the path of the Trois-Fontaines, which winds round the Falkenstein along by a little wall of dry stones. The first snow, which never lasts in the damp shades of the valleys, was beginning to melt and run down the path. Hullin got on the wall to climb the ascent. On giving an accidental look toward the village, he saw a few women sweeping before their doors, a few old men wishing each other the "Good-day" while smoking their first pipes on the threshold of their cottages. The deep calm of life, in presence of his agitating thoughts, affected him much. He continued his way pensively, saying to himself, "How quiet everything is down there! Nobody has any idea of anything; yet in a few days, what clamors, what rolls of musketry, will rend the air!"

As the first thing to be done was to procure powder, Catherine Lefèvre had very naturally cast her eyes on Marc Divès the smuggler, and his virtuous spouse, Hexe-Baizel.

These people lived on the other side of the Falkenstein, under the base of the old ruined castle. They had hollowed inside a sort of den, very comfortable, possessing one door and two skylights, but according to certain rumors, communicating with ancient caves by a rift in the rock. The custom-house officers had never been able to discover these caves, notwithstanding numerous domiciliary visits for that purpose. Jean-Claude and Marc Divès had known each other from infancy; they had gone nesting together after hawks and owls, and since that time had seen each other nearly every week at the saw-mills of Valtin. Hullin, therefore, believed himself sure of the smuggler, but he had some doubts of Madame Hexe-Baizel, a most cautious person, who would not, in all probability, have the war-like instinct sufficiently developed. "But we shall see," he said to himself as he went along.

He had lit his pipe, and from time to time turned round to contemplate the immense landscape, whose limits were extending more and more.

Nothing could be grander than those wooded mountains, rising one above the other in the pale sky—those vast heather plains, stretching as far as the eye could see, white with snow; those black ravines, shut in between the woods, with torrents at the bottom, dashing over the greenish pebbles polished like bronze.

And then the silence—the great silence of winter! The soft snow falling from the top of the loftiest pine-trees onto their lower drooping branches: the birds of prey circling in couples above the forests, screaming out their war-cry: all this ought to be seen for it cannot be described.

An hour after his departure from the village of Charmes, Hullin, climbing the summit of the peak, reached the base of the rock of the Arbousiers. All round this granite mass extends a sort of rugged terrace, three or four feet wide. This narrow passage, surrounded by the tall pines growing out from the precipice, looks dangerous, but it is safe; unless one feels dizzy, there is no danger in going along it. Overhead projects, in a vaulted arch, the rock covered with ruins.

Jean-Claude was approaching the retreat of the smuggler. He halted a minute on the terrace, put back his pipe into his pocket, then advanced along the passage, which forms a half-circle, and ends on the other side with a chasm. Quite at the farthest extremity of it, and almost on the edge of the chasm, he perceived the two skylight windows of the den and the partly opened door. A great heap of manure was collected in front of it.

At the same time Hexe-Baizel appeared, tossing, with a broom made of green furze, the manure into the abyss. This woman was small and hard-looking; she had shaggy red hair, hollow cheeks, pointed nose, little eyes, bright like two sparks, thin lips, very white teeth, and a florid complexion. As for her costume, it was composed of a short dirty woollen petticoat, and a coarse but clean chemise; her brown, muscular arms, covered with yellow hairs, were bare to the elbows, notwithstanding the excessive cold of the winter at this height; and, lastly, all she had on her feet were a pair of long shoes hanging in shreds.

"Ha! good-day, Hexe-Baizel," Jean-Claude called out, good naturedly but with a tone of raillery. "You are always fair and fat, happy and lively! It gives me pleasure!"

Hexe-Baizel turned sharply, like a weasel surprised on the watch; her red hair stiffened, and her little eyes flashed fire. However, she calmed down immediately, and exclaimed, in a curt voice, as though speaking to herself, "Hullin—the shoemaker! What does he want?"

"I am come to see my friend Marc, fair Hexe-Baizel," replied Jean-Claude; "we have some business to settle together."

"What business?"

"Ah, it only concerns us. Here let me pass that I may speak to him."

"Marc is asleep."

"Well, he must be awakened then; the time is precious."

So saying, Hullin stooped under the door, and penetrated into a cavern, whose vault, instead of being round, was composed of irregular curves, scored with fissures. Close to the entrance, two feet from the ground, the rock formed a sort of natural fireplace, on which burned a few coals and branches of juniper. Hexe-Baizel's culinary utensils consisted of an iron kettle, a stone pot, two broken plates, and three or four tin forks; her furniture comprised a wooden stool, a hatchet to split wood, a salt box fastened to the rock, and her large furze broom. To the left of this kitchen was another cavern, with a curious door, larger at the top than at the bottom, closing by aid of two planks and a cross-bar.

"Well, where is Marc?" said Hullin, seating himself near the hearth.

"I have already told you that he is asleep. He returned home late yesterday. My husband must sleep, don't you hear?"

"I hear very well, dear Hexe-Baizel; but I have no time to wait."

"Then go away!"

"Go away? It is easy said; only I won't go away. I did not walk three miles, to turn back with my hands in my pockets."

"Is it thou, Hullin?" interrupted a brusque voice coming from the neighboring cavern.

"Yes, Marc."

"Ah! I'm coming."

The sound of straw in motion could be heard; then the wooden barrier was withdrawn; and a huge frame, three feet broad from one shoulder to the other, wiry, bony, with neck and ears brick-color, and thick brown hair, appeared in the doorway, and Marc Divès drew himself up before Hullin, yawning and stretching his long arms with a short sigh.

At first sight, the physiognomy of Marc Divès seemed peaceable enough: his low broad forehead, bare temples, short curly hair coming down in a point almost to the eyebrows, his straight nose and long chin—above all the quiet expression in his brown eyes—would have caused him to be classed among the ruminating rather than the wilder animals; but one would have been wrong in thinking so. Certain rumors were prevalent in the country that Marc Divès, when attacked by the custom-house people, had never any hesitation to use his axe or carbine to decide the dispute; to him were attributed several serious accidents which had happened to the fiscal agents; but proofs were completely wanting. The smuggler, owing to his thorough knowledge of all the mountain defiles and by-roads from Dagsburg to Sarrbrück, and from Raon-l'Etape to Bâle in Switzerland, was always fifteen leagues from any place where a wicked action had been committed. And then he had such an ingenuous look! and those who connected him with sinister tales generally finished badly: which clearly shows the justice with which Providence sways the world.

"Faith, Hullin," said Marc, after having left his lair, "I was thinking of thee yesterday evening, and if thou hadst not appeared, I should have gone expressly to the saw-mills of Valtin to meet thee. Sit down! Hexe-Baizel, give a chair to Hullin!"

Then he placed himself on the hearth, his back to the fire, in front of the open door, which was raked by all the winds of Alsace and Switzerland.

Through this opening there was a magnificent view: it might be compared to a picture framed in the rock—an enormous picture, embracing the whole valley of the Rhine, and the mountains beyond, which melted away in the mist. And then one could breathe so freely! and the little fire, which glimmered in the owl's-nest, was a place to look on, with its red light, after one had gazed into the azure expanse.

"Marc," said Hullin, after a short pause, "may I speak before thy wife?"

"We are as one, she and I."

"Well, Marc, I am come to buy powder and lead of thee."

"To kill hares, is it not so?" observed the smuggler, winking.

"No, to fight against the Germans and Russians."

There was a moment's silence.

"And thou wilt want much powder and lead?"

"All that thou canst supply."

"I can supply as much as three thousand francs' worth to-day," said the smuggler.

"Then I'll take it."

"And as much more in a week," added Marc, with the same calm manner and eager look.

"I take that also."

"You will take it!" cried Hexe-Baizel. "You will take it! I should think so! But who is to pay?"

"Hold thy tongue!" said Marc, roughly, "Hullin takes it: and his word is enough for me." And holding out his large hand cordially: "Jean-Claude, here is my hand: the powder and lead are thine: but I must have my price, dost thou understand?"

"Yes, Marc: only I intend paying thee at once."

"He will pay, Hexe-Baizel, dost thou hear?"

"Eh, I am not deaf, Baizel. Go and find a bottle of 'brimbelle-wasse' for us, so that we may warm our hearts a little. What Hullin tells me rejoices me. These rascally 'kaiserlichs' will not have the easy game against us that I thought. It appears that we are going to defend ourselves, and right well."

"Yes, right well!"

"And there are people who can pay?"

"Catherine Lefèvre pays, and she it is who sends me," said Hullin.

Then Marc Divès rose, and in a solemn tone, and pointing toward the precipice, exclaimed, "She is a woman indeed—a woman as grand as that rock down there, the Oxenstein, the greatest I have ever seen in my life. I drink to her health. Drink also, Jean-Claude."

Hullin drank, then Hexe-Baizel.