Project Gutenberg's Rome, by Mildred Anna Rosalie Tuker and Hope Malleson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Rome

Author: Mildred Anna Rosalie Tuker

Hope Malleson

Illustrator: Alberto Pisa

Release Date: July 23, 2011 [EBook #36817]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ROME ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Melissa McDaniel and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent hyphenation and spelling in the original document have been preserved. Obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

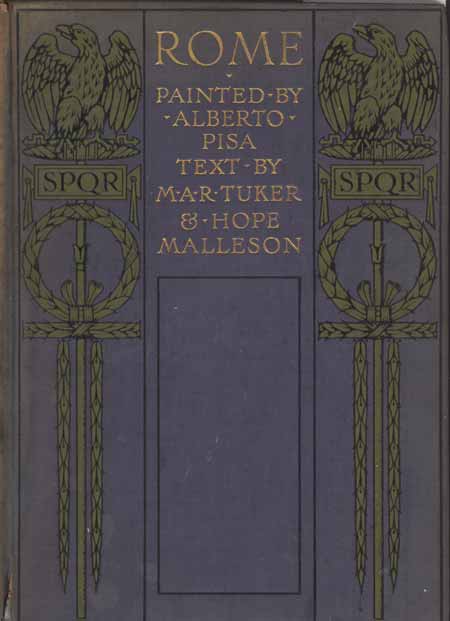

MARBLE RELIEF OF THE AMBARVALIA SACRIFICE, IN THE FORUM

The sacrifice of the suovetaurilia took place at the confines of

Rome and Alba Longa after the perlustration of the Roman ager. See

pages 15, 70.

ROME · PAINTED BY

ALBERTO PISA · TEXT

BY M. A. R. TUKER AND

HOPE MALLESON

PUBLISHED BY ADAM &

CHARLES BLACK · SOHO

SQUARE · LONDON · W.

Published April 1905

The twelve chapters in this book were all written for the[Pg v] present volume, but Chapters III., V., VIII., part of XI., and IX. have already been published in the Monthly Review, Broad Views, Macmillan's Magazine, and the Hibbert Journal.

So much has been written about Rome and Roman subjects within the last decade, good bad and indifferent, that the task of avoiding as far as possible hackneyed ground is not an easy one. We have attempted to present some aspects of Rome as we have ourselves seen it, and we have drawn on our long acquaintance with the city and above all with its inhabitants of the old school and the new.

Each chapter is the work of one writer.

Rome, 1905.

| CHAPTER I | PAGE | |

| Rome | 1 | |

| CHAPTER II | ||

| Roman Building and Decoration | 17 | |

| CHAPTER III | ||

| The Roman Catacombs | 41 | |

| CHAPTER IV | ||

| Roman Regions and Guilds | 52 | |

| CHAPTER V | ||

| The Roman Campagna | 69 | |

| CHAPTER VI | ||

| The Roman Ménage | 93 | |

| CHAPTER VII | [Pg viii] | |

| The Roman People— | ||

| I. The Italians | 112 | |

| II. The Romans | 125 | |

| CHAPTER VIII | ||

| Roman Princely Families | 159 | |

| CHAPTER IX | ||

| Roman Religion | 180 | |

| CHAPTER X | ||

| The Roman Cardinal | 200 | |

| CHAPTER XI | ||

| Rome Before 1870 | 212 | |

| CHAPTER XII | ||

| The Roman Question— | ||

| I. Before 1870 | 235 | |

| II. Since 1870 | 245 |

| 1. Marble relief of the Ambarvalia Sacrifice, in the Forum | Frontispiece |

| TO FACE PAGE | |

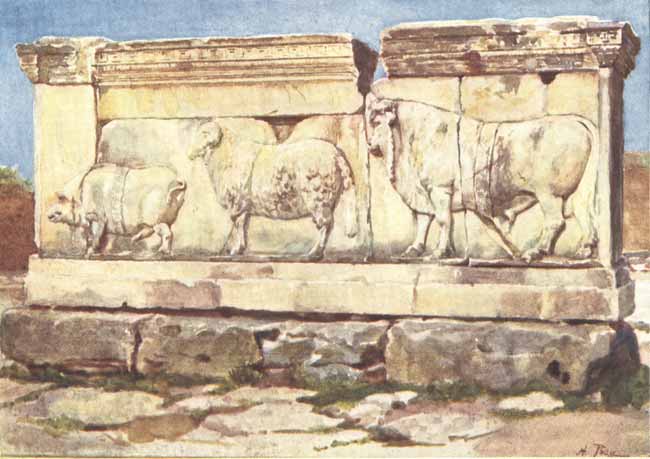

| 2. The Forum from the Arch of Septimius Severus | 4 |

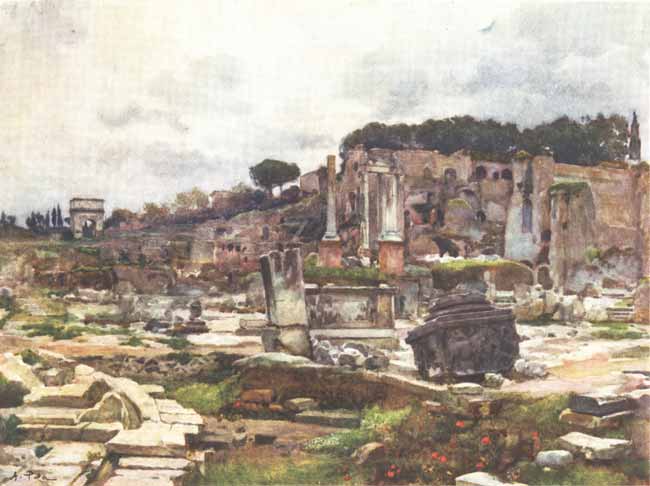

| 3. The Forum, looking towards the Capitol | 8 |

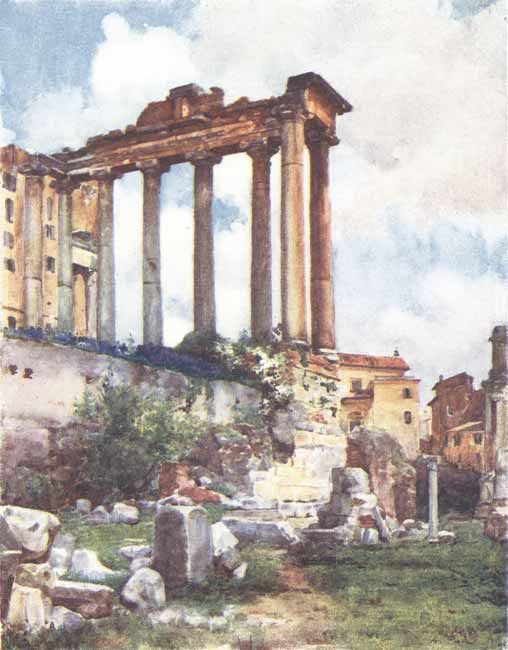

| 4. Temple of Saturn from the Basilica Julia in the Forum | 12 |

| 5. S. Peter's and Castel Sant' Angelo from the Tiber | 16 |

| 6. Temple of Saturn from the Portico of the Dii Consentes | 18 |

| 7. A Corner of the Forum from the base of the Temple of Saturn | 20 |

| 8. Temple of Mars Ultor | 24 |

| 9. Temple of Vespasian from the Portico of the Dii Consentes | 26 |

| 10. The Colosseum on a Spring Day | 30 |

| 11. The Colosseum at Sunset | 34 |

| 12. Arch of Titus | 38 |

| 13. A Procession in the Catacomb of Callistus | 42 |

| 14. Flavian Basilica on the Palatine | 44 |

| 15. Library of the House of Domitian on the Palatine | 50 |

| 16. Forum of Nerva | 54 |

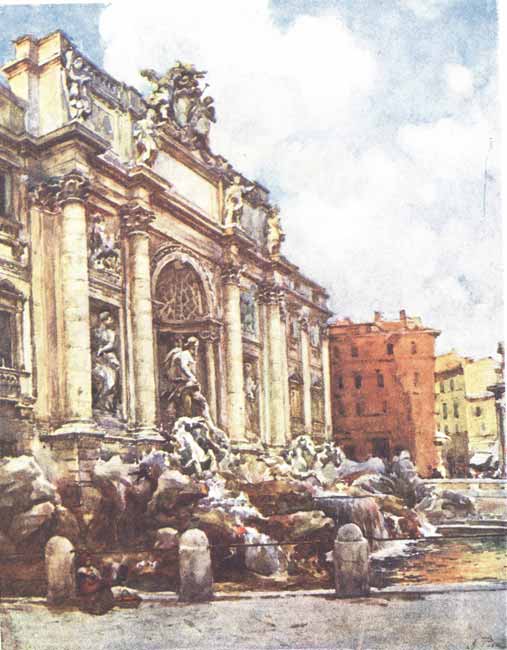

| 17. Fountain of Trevi | 56 |

| 18. Column of Marcus Aurelius, Piazza Colonna | 58 |

| 19. Pantheon, a flank view | 62 |

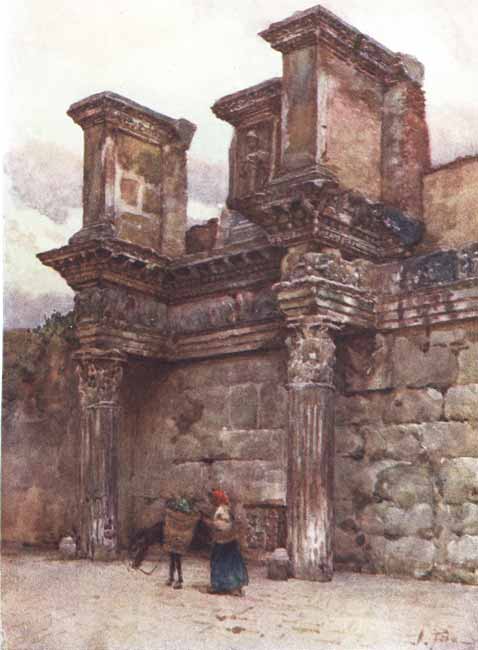

| 20. Silversmiths' Arch in the Velabrum | 64[Pg x] |

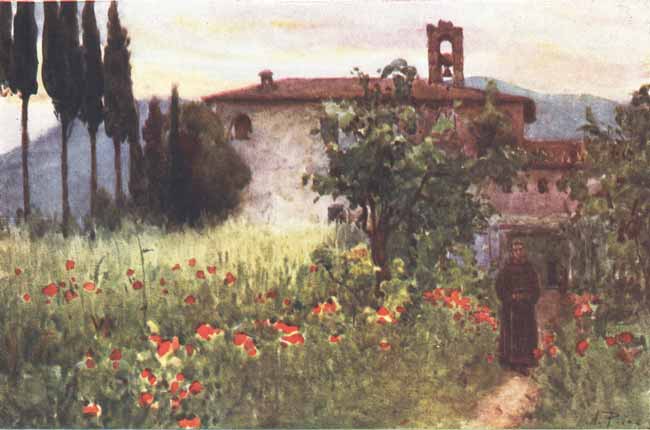

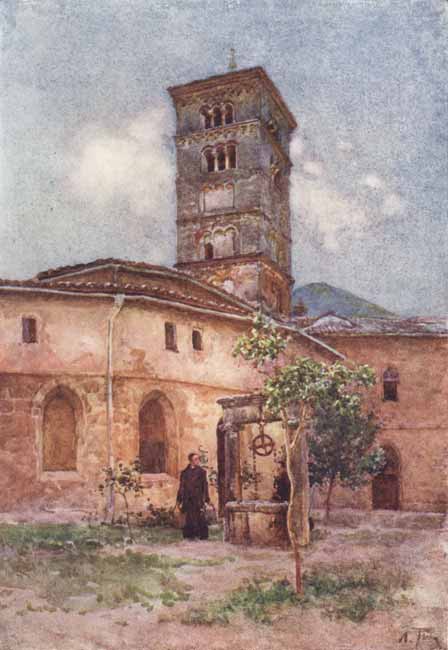

| 21. Convent Garden of San Cosimato, Vicovaro | 68 |

| 22. A Tract of the Claudian Aqueduct outside the City | 72 |

| 23. Campagna Romana, from Tivoli | 76 |

| 24. Subiaco from the Monastery of S. Benedict | 78 |

| 25. Garden of the Monastery of Santa Scholastica, Subiaco | 82 |

| 26. Holy Stairs at the Sagro Speco | 86 |

| 27. Little Gleaner in the Campagna | 90 |

| 28. Sea-horse Fountain in the Villa Borghese | 94 |

| 29. Ornamental Water, Villa Borghese | 98 |

| 30. Village Street at Anticoli, in the Sabine Hills | 100 |

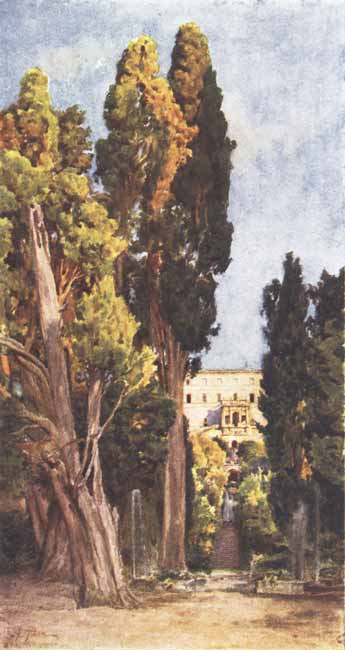

| 31. Villa d'Este, Tivoli | 106 |

| 32. In Villa Borghese | 110 |

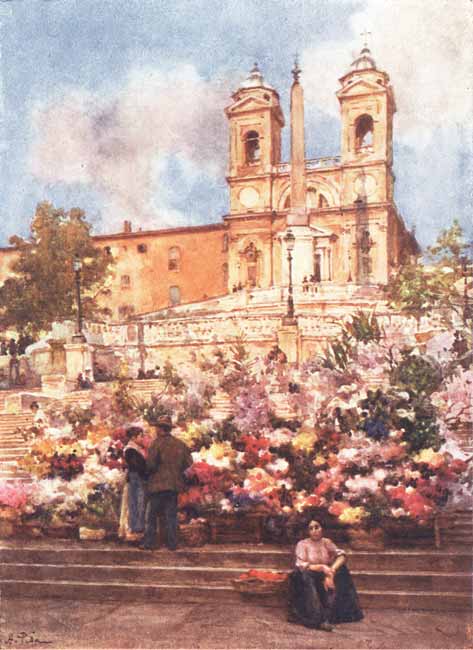

| 33. The "Spanish Steps," Piazza di Spagna | 114 |

| 34. At the Foot of the Spanish Steps, Piazza di Spagna, on a Wet Day | 118 |

| 35. Roman Peasant carrying Copper Water Pot | 122 |

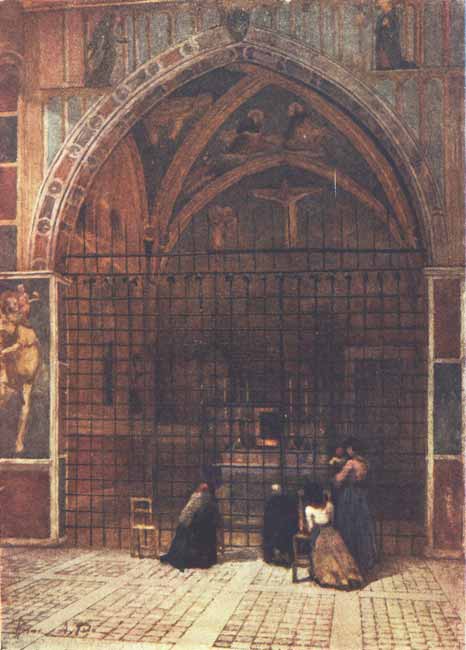

| 36. Chapel of the Passion in the Church of San Clemente | 126 |

| 37. A Rustic Dwelling in the Roman Campagna | 128 |

| 38. Procession with the Host at Subiaco | 130 |

| 39. Girl selling Birds in the Via del Campidoglio | 134 |

| 40. Entrance to Ara Coeli from the Forum | 138 |

| 41. In the Church of Ara Coeli | 142 |

| 42. Doorway of the Monastery of S. Benedict (Sagro Speco) at Subiaco | 146 |

| 43. Chapel of San Lorenzo Loricato at S. Benedict's, Subiaco | 150 |

| 44. Steps of the Dominican Nuns' Church of SS. Domenico and Sisto | 154 |

| 45. Porta San Paolo | 158 |

| 46. The Colosseum in a Storm | 162 |

| 47. Arch of Titus from the Arch of Constantine | 166 |

| 48. Mediaeval House at Tivoli | 170 |

| 49. Ilex Avenue and Fountain (Fontana scura) Villa Borghese | 174[Pg xi] |

| 50. "House of Cola di Rienzo," by Ponte Rotto | 178 |

| 51. San Clemente, Choir and Tribune of Upper Church | 182 |

| 52. Santa Maria in Cosmedin | 186 |

| 53. Chapel of San Zeno (called orto del paradiso) in S. Prassede | 190 |

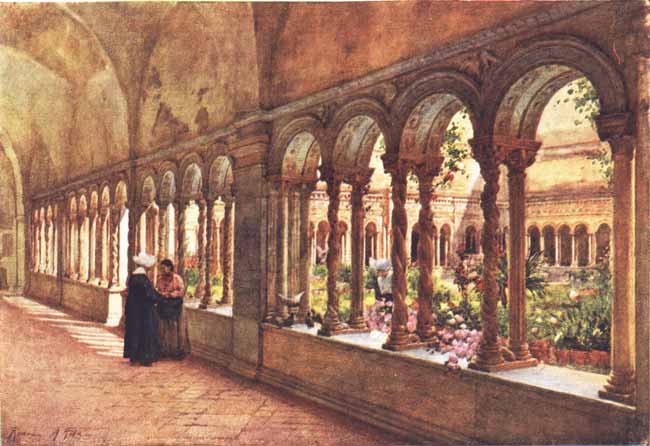

| 54. Cloisters of S. Paul's-without-the-Walls | 192 |

| 55. Cloisters in Santa Scholastica, Subiaco | 196 |

| 56. Santa Maria sopra Minerva | 198 |

| 57. Saint Peter's | 200 |

| 58. Interior of S. Peter's, the Bronze Statue of S. Peter | 204 |

| 59. A Cardinal in Villa d'Este | 208 |

| 60. Villa d'Este—Path of the Hundred Fountains | 210 |

| 61. Theatre of Marcellus | 212 |

| 62. Island of the Tiber—the Isola Sacra | 216 |

| 63. The Steps of Ara Coeli | 220 |

| 64. Steps of the Church of SS. Domenico and Sisto | 224 |

| 65. Santa Maria Maggiore | 230 |

| 66. Arch of Constantine | 234 |

| 67. Castel and Ponte Sant' Angelo | 238 |

| 68. Bronze Statue of Marcus Aurelius on the Capitol | 240 |

| 69. S. Peter's from the Pincian Gardens | 244 |

| 70. From the Terrace of the House of Domitian | 252 |

The Illustrations in this volume have been engraved by the

Hentschel Colourtype Process.

About seven hundred and fifty years before the Christian era some Latian settlers founded a town on the banks of the Tiber and became the Roman people. Where did they come from? Had they come across what was later to be known as the ager romanus from the Latin stronghold of Alba Longa, or were they a mixed people, partly composed of those men from Etruria who were already settled in the country round? In the confused pictures which tradition has handed down to us we see Latins in conflict with Etruscans, and Romulus relegating the latter to a special quarter of the city; but we also see one of the three tribes into which he divided the people bearing an Etruscan name, an Etruscan chief as his ally, and we know that while two at least of her six kings belonged to this race, the religion, the art, and the political institutions of early Rome were borrowed from that Etruscan civilisation which was at this epoch the most advanced on Latin soil.[Pg 2]

However this may be, four legends cling round the mighty founders of Rome—the Latian, the Aenean, the Arcadian, the Etruscan. The Arcadian Evander had brought with him a colony of the indigenous people of Greece, and founded a town at the foot of the Palatine sixty years before the Trojan war. But at Alba Longa there also reigned kings descended from Aeneas, who had come to Latium after the capture of Troy bringing with him the Palladium, the sacred image of Pallas. His descendant, the vestal Rhea Silvia, becomes the mother of the twins Romulus and Remus by Mars. The babes of the guilty priestess are cast adrift, but their cradle is carried down the Tiber to the foot of the Palatine, where they are suckled by a wolf, and brought up by the shepherd community already established there.

In the dim twilight of origins we recognise that Romulus is the type of the Roman people, whom he symbolises, who are found fighting the Sabine, the Etruscan, even the Latin, for existence as a nation. In the dim twilight we see all Roman things coming down the Tiber to the foot of the Palatine—the original Roma Quadrata—and we see that the nucleus of the settlement there was the cave of Lupercus, the Italian shepherds' god, identified later with the Arcadian Pan. This cave was just above the site of the present church of Santa Anastasia; here grew the wild fig-tree in whose roots the cradle of Rhea Silvia's babes became entangled, and here was the hut of Faustulus their foster-father.

The Grotto of Lupercus is the oldest sanctuary of[Pg 3] kingly Rome. For the people were shepherds. Other nations had risen under shepherd kings who led their people to war, but no other people had become world conquerors; no other people had been equally skilled in the arts of war and the arts of peace, the arts of the plough and the arts of the spear, in the self-discipline, the heroic devotion, the unity of purpose, of the men who once carried in their breast the destinies of the known world.

The story is aptly figured in the person of the god Mars, who was the reputed father of Romulus and Remus. The Roman god was at first an agricultural divinity—the "spears of Mars" were the rods with which the shepherd owner marked his boundaries. When, under the influence of Greece, Mars became the god of battles, the boundary marker of the fields became his war weapons. But if the Roman knew how to beat his ploughshare into a sword, he also knew how to return from the sword to the plough. The one was never far from the other—they put him in possession of those two ways of inheriting the earth, multiplying and subduing, producing and combating. Thus the pastoral legend never died out from the land of Saturn, and in the proudest flush of victory, when the relics of the hastae martis were shown to the triumphant followers of Mars, there was present to the soul of the Roman the image of the father of Romulus covering the land with gigantic strides to strike these same hastae into the soil as a sign of possession, the emblem of primitive law.

THE FORUM FROM THE ARCH OF SEPTIMIUS SEVERUS

In the left corner is the lapis niger, the traditional tomb of

Romulus. Facing us is the Arch of Titus, and to the right is the

Palatine.

Two hills in Central Italy and a swamp between them provided [Pg 4]the theatre of perhaps the greatest millennium in human history. On the one hill were the Latins—or let us call them the Roman people—the site of Roma Quadrata the foster-land of Romulus, the birthplace of Augustus, the hill which has given its name to the imperial palaces of the earth. On the other were the Quirites and the site of the Sabine arx, that Capitolium so-called, says Montfaucon, "because it was the head of the world, from which the consuls and senators governed the universe." Whenever the marshy ground between them was passable, the Latins and Sabines descended the steep declivities of their hills and transformed it into a battlefield. But even in these early days they felt the need of a comitium where the rival chiefs could meet to decide upon terms; and in no long space this battle-ground became the nucleus and pledge of the political greatness of Rome.

For the Forum symbolises all human civilisation. It is the symbol of the common meeting ground—the common sentiments and needs—of human beings, where rancours are laid aside for the business of life—its common but its noblest business, civic, "civilised," pursuits. It is the symbol of human greatness also, for the Roman never suffered the common necessities to force upon him an ignoble peace. The battle-ground became the centre of civic life, but only on condition that the interests for which men should combat were never sacrificed to the interests for which men should co-operate. Through the symbolic trait d'union of[Pg 5] the Forum, two fortresses of barbarians became the nucleus of the city which ruled the world, and their people the imperial people of history.

The city on the Palatine had been extended so as to include the town of the Sabines or Quirites on the neighbouring Quirinal hill, before the first king, who was born in the Sabine country, was called to rule the Romans. The Capitol at this time was a spur of the Quirinal, and so remained until Trajan dug away a part of the latter to lay the foundations of his forum. The Etruscans lived on the Caelian and the two horns of the Esquiline hills; the former was incorporated in the primitive city, but the Esquiline and Viminal were not enclosed until the time of Servius Tullius when Rome first became "the city on Seven Hills." The Aventine where Remus had wished to build the city was colonised by the conquered Latin towns in the reign of Ancus Martius, and this isolated hill, overlooking the Tiber on one side and the campagna on the other, still haunts the imagination with its melancholy beauty, its pariah history, as though it embodied the undying protest of Remus, an unceasing claim upon Roman justice. The varied and interesting Christian memories here, which begin with the titulus of Priscilla and Aquila, are continued in the Priory of the once international Order of the Knights of Malta, recording the noblest effort of the lay world during the middle ages—the institution of chivalry; and in the modern Benedictine house of Saint Anselm—our English Anselm.

The Janiculum, the site of a fortress built by Ancus[Pg 6] Martius against the Etruscans, was not enclosed within the city walls till the time of Aurelian; the Vatican hill was only enclosed in the ninth century by Leo IV. All these hills were once steep defences against enemies in the surrounding country; now that there are no longer any enemies the Romans appear bent on abolishing the hills, and the mania for planing and razing is carried to an extent which must seem nothing less than childish to the visitor. The Viminal has become almost indistinguishable since the Villa Massimo was pulled down, and only the name Via Viminale, which replaces the older Via Strozzi, indicates the hill which lay between the Quirinal and the Esquiline. Some idea may be gained of the original steepness of the hills when we realise that in the memory of the Romans the road past Palazzo Aldobrandini—on a slope of the Quirinal—used to be at the level of the top of the high wall which now surrounds it. The Capitol was only approachable from the Forum, and was never connected with the city on the hither side until the construction of the historic steps of Ara Coeli, one of the rare works undertaken by the Romans during the absence of the popes in Avignon.

The Tiber is now but a narrow stream in the midst of its ancient bed. The Romans had never embanked the swift-flowing river, and the enormous deposits of the yellow sand which give it its traditional colour, and which threaten to completely dam the river by the island of the Tiber, may afford the explanation. The inundations of 1900 in fact reached the same level as[Pg 7] those of 1872, as we may see recorded in the neighbouring church of Santa Maria in Cosmedin. Few spots in Rome exceed in varied interest the isola sacra which with its two historic bridges the pons Fabricius and the pons Cestius spans the Tiber at the heart of the city. Here was the temple to Aesculapius, whose worship had been introduced into Rome during a time of pestilence in obedience to the Sibylline oracles. The island itself thereafter assumed the form of a huge stone ship, faced with travertine, the prow with the sculptured staff and serpent of the god being still clearly visible; and here Greece and Rome met a civilisation and an art still older than their own, for the mast of this great ship is formed by an Egyptian obelisk. Hard by is the district where the Romans, who had borrowed from them their gods and their cult, compelled the "turba impia" ("the impious crowd") of Etruscans to dwell; while the walled enclosure in which, from the eleventh century onwards, Christian Rome obliged the Jews to live, is approached by the Fabrician bridge, as we may gather from the inscription in Hebrew and Latin on the little church of San Giovanni Calibita, beneath a painting of the Crucifixion, which says: "I have spread forth my hands all the day to an unbelieving people, who walk in a way that is not good."

In the early twelfth century Otho III. brought, as he believed, the body of the Hebrew apostle Saint Bartholomew to this island, as 1400 years earlier the cult of Aesculapius had been brought there from Greece. The city of Beneventum had, however, it is supposed, palmed off on the emperor the body of Saint Paulinus of Nola which rests in the church dedicated to the apostle by the side of that of Saint Adelbert the apostle of the Slavs. The Franciscans came to the isola sacra in the sixteenth century, and one of the friars of Saint Bartholomew's is the popular dentist of the poor from all quarters.

Here, then, in the midst of the river which determined the site [Pg 8]of the cosmopolitan city, is a spot to whose history Egypt, Greece, Etruria, Palestine have contributed—Aesculapius, "one of the Twelve," the Christian Slavs, the Saxon Otho, Francis of Assisi. In Paulinus of Nola we are reminded of the earliest Western monasteries, and the Franciscan friars represent for us the thirteenth-century revival of the religious spirit in Italy. What more? In the red-gowned confraternity of the island we are put in touch with an institution which seems to be as old as human history, with those burial guilds, sanctioned by Roman law, under shelter of which the first Christians obtained a legal footing for themselves and their cemeteries long before their religion was tolerated.

The vicissitudes of the city have made certain features of its life as eternal as itself. Through the middle ages it was the sanctuary and since the renascence of classical learning it has been the museum of Europe. Long before there were any kind of facilities for travelling every one came to Rome. A procession of people from every race under heaven, in every variety—every excess and defect—of costume, has passed along the streets under the observant but unastonished eyes of the[Pg 9] blasé Roman; and when a lay pilgrim in a brown tunic, hung with rosaries, and carrying a crucifix taller than himself, walked last year out of Saint Peter's among the Easter crowd, no one noticed him. The modern city in becoming the hostess of the other provinces of Italy is approximating in size to the Rome of the early empire; but the Rome of the popes made no sort of provision for the influx of Europe. The Inn of the Bear, in the street of that name leading to Ponte Sant' Angelo, provided the best accommodation; and here, it is said, Dante himself had lodged. It is but a hundred years ago that a pavement was placed for pedestrians, and then only one side of the Corso boasted a narrow footpath. The streets were encumbered with hucksters' stalls, with refuse, dirt, and stones; the nights were dark as pitch, and hygiene was only hinted at in the marble affiches which may still be seen at certain old street corners announcing that monsignore the way warden would visit with a fine of 25 scudi and divers bodily pains the practice of emptying every kind of refuse into the side streets.

Now that the city is emerging from the chrysalis of the middle ages the cry of "Vandals!" goes up on all sides. But Rome has always been destroyed. Not even her moral vicissitudes give her a greater right to be called "the eternal city" than her survival of the material ruin to which she has over and over again been subjected. That Goth and Vandal have not wrought more havoc than emperors, people, and popes is recorded in the pasquinade on Urban VIII. (Barberini),[Pg 10] who stripped the bronze off the Pantheon to adorn the baldacchino of Saint Peter's:—Quod non fecerunt Barbari, fecerunt Barberini. It is a curious coincidence that the inscription commemorating the victories of Claudius in Britain, in which our kings are irreverently spoken of as "barbarians," should now grace the garden of the Barberini palace in Rome. Tempora mutantur nos et mutamur in illis.

One factor only has been constant in the vicissitudes of Rome—barbarian invaders, rescuers of popes, foreign intruders, internecine brawlers, the flights and elections of popes, have each brought the opportunity for wholesale pillage. To the Roman love of destruction must be added the love of the large and superfluous: from the time of the emperors to the present hour when sites and buildings are doomed on all hands in order that the colossal monument of Victor Emmanuel II. may dominate the centre of the Roman tramway system—while the House of Augustus is unexcavated and his tomb is dishonoured—the Romans have proved themselves to be the sons of those who killed the prophets, by building or desecrating their sepulchres. But when "new Rome" is condemned let us not forget that it has given us what the learning and the riches of the most munificent popes never compassed—an excavated Forum.

There is no Mayfair and no Seven Dials in Rome. The poor live, and have always lived, cheek by jowl with the rich: a palace in the Ghetto and a hovel in the Corso have each existed without offence. This brings us to another permanent feature of Roman life—the[Pg 11] beggars. Rome has always lived on the foreigner, and it has always had troops of beggars patrolling its streets, in the time of the Antonines as in that of Gregory the Great, or as in that of the latest of the sovereign pontiffs, Pius IX.; and the cheerful-faced beggar who was licensed by this pope to sit by the statue of Saint Peter lived to the closing years of the century and gave a dowry of 200,000 francs to his daughter on her marriage. The difficulties which met the Roman of the era of Gregory the Great when pest and the transition to the agricultural system of coloni threw the serfs upon the streets, met the government of Italy when after September 1870 the whole motley crowd which had been the recipient of the Christian system of alms-giving was in its turn suddenly thrown upon the streets of the city. Those who remember the "seventies" or the "eighties" in Rome remember the menacing manner in which "alms" were "asked," how near together were blessing and cursing, and how unfrequented roads and hills were beset by sturdy beggars, lineal descendants of the brigand who placing his hat in the roadway levelled his gun at you as he proffered the request: "For the love of God put something in that hat."

Papal charity pauperised a whole people: notices in the streets on wet days announced the free distribution of bread in the Colosseum; doles of bread were given by all the parish clergy to the practising members of their congregations. The men women and children who had passed their time doing odd jobs in churches, following[Pg 12] viaticum and funeral processions, and providing a church crowd on all occasions, were suddenly called upon to make some concession to the modern spirit—hawking a bunch of crumpled flowers, a box of matches or a couple of bootlaces up and down the streets, in and out of the restaurants, these latest recruits to the commercial spirit exchanged the atmosphere of the sacristy for the busy whirl of trade without ceasing to be what they had always been, beggars pure and simple. Successful attempts are now being made to put down begging. The great and real distress which exists in the city is mainly due to the excessive rents and the terrible overcrowding—in the San Lorenzo quarter the modern poor of Rome may be found herded together with five, six, and even seven families living in one room. The mania for building in the "eighties" led to the "building crisis"; streets of unfinished houses mock the houseless poor and the "improvements" of the city are gradually demolishing the poorer dwellings. Amidst this misery it is still the old Roman population which receives most help; they are known in their parishes, and the old established subsidies and dowries come their way.

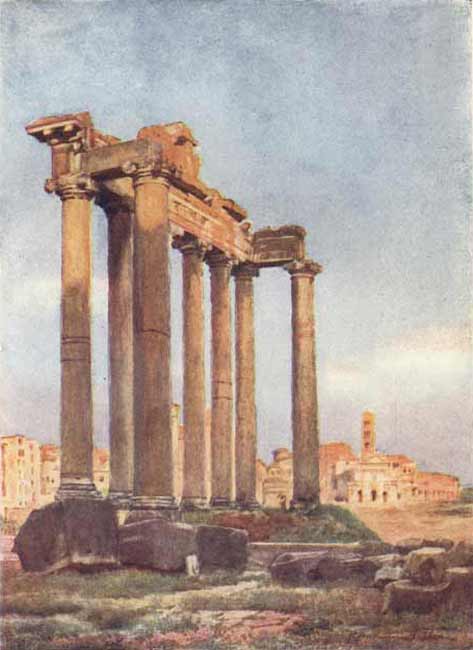

TEMPLE OF SATURN FROM THE BASILICA JULIA IN THE FORUM

The Capitol is to the left. The temple is built at the foot of the

Capitol hill. See pages 3, 13, 30, 91.

The population of Rome has varied as much as its fortunes. The maximum was reached in the time of the Flavian emperors—2 millions, but even in the time of Augustus the inhabitants probably numbered 1,300,000. A period of three hundred and fifty years, which brings us to the date of the "Peace of the Church," sufficed to decrease this number by more than[Pg 13] a million (a.d. 335). After a thousand years of Christian domination the population of the city had sunk to its minimum, 17,000 (a.d. 1377). Even in the reign of the magnificent Leo X. it was not more than 30 or 40 thousand. From the beginning of the seventeenth century when it exceeded 100,000, it steadily increased, till in 1800 the population numbered 153,000. But during the "empire," 1812, it fell to 118,000. Ten years after "the Italians" entered Rome it had increased by 79,000, to 305,000. The last census, 1900, shows a resident population of 450,000—not a third of its classical total—and Naples is still the most densely populated city of Italy.

The Greek tradition in Rome seems summed in the Palatine, the hill of "Pallas"; but the Capitol, the hill of Saturn, sums Italy itself. The one represents the Roman Empire, the other the Roman Commune—those liberties and that self-government which began with the entry of the gentes and the formation from among them of the Roman Senate, and which were never to be abolished. The Palatine has not been inhabited since the officials of the Exarchate abandoned it in the eighth century; but the life of the Capitol has never been intermitted; it has never ceased to represent all the moments in the life of the Roman people. This distinction is sharply drawn to-day: the Palatine is a hill of majestic ruins visited only by the tourist, the Capitol is still the seat of the municipality of Rome, ascended by every couple for the celebration of their marriage, and[Pg 14] its registers signalise every young life born to the city.

The municipal franchises of Italy have played a large part in her history, and that of Rome is no exception. Moreover the Senate of Rome, the heads of each gens from among the original settlers, and the Populus, who be it remembered were the gentes and were never synonymous with the plebs, represented two constant facts and factors—a free Senate and free municipal government by the Populus Romanus. These flourished in the middle ages as they had flourished in the classical city, and it was thus easy for Cola di Rienzo to restore them when the popes had abandoned the city to its fate. Papal letters to Charlemagne's predecessors were indited in the name of the Senate and people of Rome—a custom which influenced the early government of the Roman Church herself, for her letters to other Christian Churches were written in the name of "the Roman Church," even when, as in the case of Clement's epistle, they were the actual handiwork of the then head of the Christian community. Again, when Pepin obliged the Lombard king to cede the exarchate of Ravenna not to the emperor but to Rome, the words employed were: "to the Holy Church and the Roman Republic." Even in the time of the proud Innocent III. the city was still governed "by the Senate and people of Rome," and when the Romans again tired of their Senate—as tradition says they had done when they made Numa king—they created in its place a supreme magistrate who was designated "the Senator,"[Pg 15] one of whose duties was to maintain the pontiff in his See, and to provide conveniently for his safe conduct and that of the Sacred College when journeying within his jurisdiction. The extent of this jurisdiction is perhaps all that now remains of the power once held by the Senate and Roman people. The municipality of Rome is the largest in the world; it is conterminous with the whole Roman agro, so that its history is inseparably linked with that of the Roman boundaries as well as with the life of the Roman people.

The outward and visible sign of these primæval Roman liberties is the tetragram S.P.Q.R.—Senatus Populus Que Romanus (the Roman Senate and People), which took the place of the earlier formula Populus Romanus et Quirites, and it is of the Sabines, not of the humble conjunction, that that Q still reminds us. All down the centuries we may recognise those four letters—surmounted in imperial times by an eagle—crowning the standard of the Romans, carried far and wide not only through the streets of the city and to the uttermost ends of the earth, but in that religious perlustration of the ager when the ambarvalia rites were celebrated at the Cluilian Trench which separated Rome from Alba Longa, the site of the combat between the Alban Curatii and the Roman Horatii. One of the finest remains in the Forum is the marble relief which represents the suovetaurilia, the sow, sheep, and bull sacrificed on this occasion. That Roman greatness which came to be synonymous with confines as large as the known world, had risen with the recognition of[Pg 16] these sacred limits, limits which still define the Roman municipality—the symbol of Roman liberties.

The Pragmatic Sanction and the world power of Rome! Can two things be more disparate? Yet the version which renders S.P.Q.R. into Si Peu Que Rien must surely be laid at the door of "Gallicanism"—it points to an ecclesiastical not a political diminutio capitis. The tract of the city which we see from the terrace on the Pincian hill, looking towards the Janiculum, has been called the most historic plot of land in the world. Is it without reason that the furthest point of this unequalled panorama is the dome which Michael Angelo erected over the tomb of S. Peter? Three mighty civilisations—the Etruscan, the Roman, the Christian—resulted in the foundation of two world empires. Rome is now entering on a third existence, its existence as the capital of Italy, but has it suffered thereby no diminutio capitis? Is it not a fact that the classical and the ecclesiastical represented her only world-wide destinies, the only life of Rome which penetrated as truly beyond the city as within its classic confines? Has not the papacy, with all its faults, been the actual link connecting ancient and modern Rome, preserving unbroken the tradition which gave her, beyond her ritual boundaries, the government of the world without?

Shepherds' huts clustered upon a hill top whose base is washed by a swift yellow river rushing to the sea not far distant. This is the first faint foreshadowing of the existence of Rome which reaches us dimly across the centuries. These shepherd settlers had chosen a site propitious for the foundation of the great city which was to be raised upon those grouped hills by the skilful hands of their descendants, for the necessary building materials lay close at hand in lavish profusion. One of the neighbouring hills, known later as the Janiculum, and parts of another, the Pincian, yielded a fine yellow sand. Beneath the surface soil was volcanic rock, which, in a prehistoric age when the campagna was a sea-bed and waves lapped against Monte Cavo, had been poured out in great liquid streams from volcanoes amongst the Alban hills and at Bracciano. Close at hand in the plain lay immense beds of a chocolate-brown earth with which later builders were to manufacture cement.

The makers of Rome therefore had only to quarry their building stone on the very site of their city, and[Pg 18] we can still recognise in the few fragments that have come down to us the rectangular blocks of brown tufa used in the first period of her history. These earliest monuments, the walls of Servius Tullius and the vaults of the Mamertine prisons, were the direct outcome of a period of Etruscan dominion, and one of the first great works undertaken in the growing city, the draining of the swamps of the Forum, Campus Martius and Velabrum, was due to Tarquinius Priscus, the immense cloacae built for the purpose being still in use, and their masonry as strong as when they were constructed about 603 b.c. The two Etruscan kings, Tarquinius Priscus and Tarquinius Superbus, built the first triple shrine on the Capitol dedicated to the three Etruscan gods, Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, and the primitive Roman temples, consisting of a simple cella with a peristyle, were doubtless Etruscan in character and were decorated with terra-cotta and bronze in the Etruscan manner.

The Romans were born builders and engineers, and in these branches they quickly outstripped their predecessors and instructors. If they were deficient in artistic originality, they evinced a readiness to imitate and a power of appreciating skill and proficiency in the arts wherever they met with them, and their practical and utilitarian spirit taught them how to adopt and improve upon experience and guided them in the choice of right materials.

TEMPLE OF SATURN FROM THE PORTICO OF THE DII CONSENTES

One of the earliest monuments of Rome; originally built in the reign

of the last of the Tarquins or the first years of the Republic, but

twice reconstructed during the Empire. It served as the Treasury of

Rome. The granite columns with marble capitals are of the Ionic order.

See pages 30, 181.

A period when the influence of Greece predominated succeeded the first epoch in the building of Rome,[Pg 19] and to this time must be ascribed the adoption of the Greek models for public buildings, for circuses, baths, and basilicas. Ionic, Corinthian, and Doric columns were imported into Rome, the latter undergoing some modification to suit the Romans' more florid taste. The temples became Hellenic in style. The small cella was built within an open court surrounded by arcades from which the people assisted at the sacrifices. The altar stood in the open court. Later, windows were introduced into the building, and the openings were filled in with a bronze grating similar to that still in perfect preservation over the door of the Pantheon, or with a perforated marble screen, fragments of coloured glass being inserted in the interstices of the pattern. By the third century there were 400 temples in Rome, but the simple form of the early buildings was hidden with excessive ornamentation, and frieze and cornice were loaded with carving and figures.

The basilica, or kingly hall of justice, was a rectangular building divided into a central portion or nave and side aisles by rows of columns under a horizontal architrave. The columns were in two tiers, the upper one enclosing a gallery which was reached by a flight of stairs springing either within or without the building. The entrances were at the sides, and one extremity, and in some cases both were extended to form a semicircular apse or tribune where stood the judge's seat. A marble screen, the cancellum, separated this portion from the rest of the building, and this constituted the bar to which the accused were brought;[Pg 20] just beyond stood the altar, where incense burned; and here, during the persecutions, Christians were arraigned and bidden to throw incense on the fire as a sign of recantation.

These great buildings served as courts of justice and for the transaction of business, and those which stood upon the fora were in some instances so large that several cases could be conducted in them at once. Before the Empire the nave was probably unroofed or covered only with an awning, and the upper galleries were entirely open so that their occupants could at will attend to the proceedings within the basilica or watch the games and events without. Similarly a single rail or low partition only separated the open colonnades below from the Forum. Curtains could be drawn across these to shut out importunate onlookers and to muffle the sounds of street traffic, but it is evident that the basilica precincts were regarded as a place of familiar rendezvous by the idlers in the Forum, as the gaming tables scratched in the flooring of the Julian basilica testify.

A CORNER OF THE FORUM FROM THE BASE OF THE TEMPLE OF

SATURN

The column of Phocas, erected in honour of the Byzantine emperor who

was the contemporary of Gregory the Great, faces us, and to the right

are the columns of the temple to Antoninus Pius and Faustina, now the

façade of the church of San Lorenzo in Miranda. The columns are of

cippolino marble. See page 32.

The era of thermae or public baths began with Agrippa in 27 b.c., and by the end of the third century eleven such existed in Rome exclusive of the smaller baths or balnae, of which there were 850. Nero, Titus, Trajan, Septimius Severus, Caracalla, Diocletian, were all builders of thermae. These huge edifices were a great deal more than public baths. They were a Roman form of the gymnasia of the Greeks, and the colossal ruins that remain can give but the barest idea of what they must have been at their best. They included immense[Pg 21] halls and courts for athletic displays, vestibules, concert rooms, picture galleries and libraries, pleasure grounds decorated with statues fountains and shrubs and surrounded by open porticoes. Feasts, concerts, and entertainments were provided, and pleasant hours could be whiled away within their walls by the gilded youth of Rome. The baths of Diocletian, of which the church of S. Maria degli Angeli is a magnificent fragment, could accommodate 3600 bathers at a time, those of Caracalla 2000. An army of slaves and attendants waited upon the bathers and sped upon their errands along underground passages from one end of the building to the other. Ruins of the thermae of Caracalla and of Titus are still standing. Out of the colossal vaults and walls of Diocletian's baths have been constructed two churches, a monastery, a large museum, and a variety of storehouses, warehouses, stables, and cellars.

Equally remarkable was the Roman system for supplying their city, their thermae, and their 1350 street fountains with pure water.

Appius Claudius was the first to collect the water from springs amongst the mountains in the neighbourhood of Rome and to bring it across the campagna. This was in 313 b.c., up to which date the inhabitants of the city had depended for their water supply upon the Tiber and upon sunken wells. Following in the steps of Claudius, fourteen aqueducts whose united length measured 360 miles were built at various times. They varied in length from 11 to 59 miles and their course lay sometimes under ground and sometimes 100 feet above it,[Pg 22] while the amount of water they poured daily into Rome has been estimated at 54,000,000 cubic feet.

Four of these ancient aqueducts are still in use. The Virgo, built by Agrippa in 27 b.c., and now known as the Trevi; the Alexandrina, constructed by Alexander Severus (222-235), probably to supply his own baths, and now known as the acqua Felice; the ancient Trajana, now Paola, and the Marcian, restored by Pius IX. The Marcian was always considered the best drinking water, and the Trevi being a softer water was preferred for bathing purposes.

The amphitheatre alone was, perhaps characteristically, a building of purely Roman origin. Intended for shows and fights of gladiators and wild beasts, these were at first temporary wooden structures. The only stone predecessor to the great Flavian amphitheatre was a smaller building in the Campus Martius, the work of Statilius Taurus in 30 b.c. The Colosseum was begun by Vespasian in a.d. 72, was dedicated eight years later by Titus, and was completed by Domitian. It stands upon the site of Nero's artificial lake, is one-third of a mile in circumference, covers some 6 acres of ground, and is 160 feet in height. It could seat 87,000 spectators, and its staircases, galleries, and entrances are so admirably planned that this crowd of sight-seers must have found their seats and filed out when the show was finished with little delay and difficulty. The numbers of the entrances, cut in stone, can still be seen over each of the arches. The Colosseum is built entirely of travertine, the blocks are fitted together without mortar and are[Pg 23] studded with holes from which the greedy despoilers of the middle ages wrenched the metal clamps. In spite of its having been used as a fortress and served as a stone quarry for centuries, it is still one of the most magnificent of the monuments of Rome.

The solidity of the public buildings seems to have been in marked contrast to the flimsy nature of the common dwellings or insulae. In the time of Augustus these numbered 46,600, the domui, or houses of the rich, 1790. The former were roofed with timber or thatch. As land was dear, they were often of several stories and perilously high; many of them were built of unbaked bricks with projecting upper floors, and they were constructed with wooden framing filled in with rush and plaster, so that when a fire broke out in the city whole regions were laid waste in a few hours. As a measure of safety Augustus limited the height of the insulae to 70 feet, and Trajan reduced this again to 60 feet, while a distance of 5 feet between each house was prescribed by the law of the Twelve Tables.

The volcanic tufa used by the earliest Roman builders was discarded gradually in favour of better materials. Peperino, a grey-green volcanic stone from the Alban hills, began to take its place, and was used for the construction of the Tabularium in 78 b.c. and for Hadrian's mausoleum. It was cut in the same way in large rectangular blocks, clamped together during the Republican and early Imperial periods with iron. Mortar was not used till later, and at first served only to level the surfaces of the stones; it came into use for binding[Pg 24] bricks together only at a later and degenerate period of architecture. Travertine was adopted towards the first century b.c. It is a cream-coloured stone hard and durable though easily calcined by fire, formed by deposit in running water. It was quarried at Tivoli and on the banks of the river Anio, where it is still plentiful. To the present day the quarries are worked at Tivoli, and the stone is brought to Rome on waggons drawn by immense white oxen which pace majestically along the dusty roads beneath the goad of their wild-looking drivers.

The chocolate-brown earth imported from Pozzuoli or dug from beds in the campagna, is known as pozzolana, and early in the history of Rome her builders discovered that when mixed with lime it made a remarkably strong cement. As such they used it for foundations, for the lining of walls and ceilings. With pieces of brick and stone a concrete was formed which was poured in a liquid state between wooden casings, and when set proved to be one of the hardest and most durable of the materials used. It was the strength of this concrete which enabled the Roman builders to give the vaults of their baths and basilicas such an enormous span; and it could be used for the flooring of upper stories without beams or supports. When especial lightness was required, the concrete was made with broken pumice stone.

TEMPLE OF MARS ULTOR

The temple erected by Augustus in his Forum to the God of War under

the title of Mars the Avenger. Only the upper part of the ancient arch

of the Forum, now known as Arco de' Pantani, is visible. This

represents the first imperial building in Rome. See pages 3, 30.

After the first century b.c. concrete became a favourite building material. The walls so made were lined with stucco and faced without in various fashions, the variety[Pg 25] of the facing determining with considerable accuracy the date of the fabric. The earliest facing, of the first and second century b.c., was of irregular blocks of tufa set in cement, and is known as the opus incertum. This was replaced in the middle of the first century b.c. by tufa blocks cut in squares and set diagonally giving the appearance of a network and hence known as opus reticulatum. In or after the first century a.d. this fashion was superseded by a facing of triangular bricks set point inwards, and by the end of the third century bricks were mixed with the opus reticulatum, a style known as opus mixtum. To the casual observer the narrow brown bricks of the ruined buildings of ancient Rome seem to play an important part, but, with few exceptions, they are merely a brick facing upon concrete.

Up to the first century b.c. there was little or no splendour or decoration introduced into the buildings of Rome, and the city of Augustus' inheritance was a city of sober-hued, volcanic rock. When marble was first sparingly used, Livy reprobates it as too showy and extravagant. Notwithstanding, the fashion rapidly spread, first in the embellishment of public buildings, then for private houses as well until in the first century of the Empire it became a common building stone.

For nearly three centuries it was imported into the city in a continuous flow from the quarries of Greece and Egypt. The native Luna marble, the modern Carrara, was not at first worked, but thousands of slaves and convicts toiled in the quarries of the Roman provinces. The great blocks were numbered and stamped[Pg 26] with the name of the reigning emperor and shipped off in the great triremes across the Mediterranean to Ostia. Thence the trading vessels were towed by oxen up the river to Rome, their slow progress ceasing with nightfall, when they were drawn up and moored to the banks till next morning, bands of vigiles watching over the safety of their cargoes and restraining their lawless crews from acts of brigandage. At their journey's end, the cargoes were unloaded upon the marble wharf beneath the Aventine; here unused blocks still lie upon the site of the once busy Marmoratum, now a deserted quay beside a deserted river; and the harbour of Ostia, built by King Ancus Martius at the river's mouth, is now four miles inland.

Occasionally a granite obelisk was brought from Thebes or Heliopolis to adorn an imperial circus. That now in the Lateran Piazza is 108 feet in height and weighs 400 tons. Ships had to be built on purpose for the task, and one of these was so enormous that after safely conveying the Vatican obelisk to Rome, it was sunk by the Emperor Claudius to serve as a breakwater for the harbour at Porto. When the laden ships arrived at the Marmoratum the obelisks were hauled on shore by men and horses and then dragged and pushed on rollers along the streets by gangs of workmen. Forty-eight obelisks were once erected in Rome, of which thirty have disappeared and left no trace.

TEMPLE OF VESPASIAN FROM THE PORTICO OF THE DII

CONSENTES

Built in honour of the first Flavian Emperor by his sons Titus and

Domitian. The three remaining Corinthian columns are of Carrara

marble. The Arch of Septimius Severus to the right was dedicated to

the emperor and his sons Caracalla and Geta in a.d. 203, to

commemorate their Parthian victories. It is of Pentelic marble. The

church of Santa Martina in the background is near the site of the

Senate House. See pages 31, 32.

While the fashion for marble lasted, no material was considered too rare or too costly. Parian marble, the most beautiful of all white marbles, from the island of[Pg 27] Paros; Pentelic marble from Pentelicus; Hymettan marble from the mountains of Attica; rich yellow giallo antico from Numidia; cippolino with its beautiful green waves from Carystos; purple pavonazzo from Phrygia; black marble from Cape Matapan; green and red porphyries from Egypt; alabaster from Thebes; serpentine from Sparta; jasper and fluor-spar from Asia Minor; lapis lazuli, with which Titus paved a chamber in his baths, from Persia, besides countless varieties of the so-called Lumachella marbles and rare and beautiful breccias.

There arose in Rome an army of marble workers, cutters and sawyers, polishers and cleaners, carvers of simple mouldings and of inscriptions, and more skilled sculptors of ornament and of statues and busts.

Coloured marbles were first used in small pieces for making mosaic pavements. This art was introduced from Greece some time in the first century b.c., and in its simplest form was an arrangement of smooth pebbles in a rough pattern on a bed of cement. As the art developed, cubes, lozenges, and hexagons of travertine and grey lava were cut and fitted together in simple patterns. Then cubes of coloured marble were used, and the designs, of figures and flowers, became more elaborate. The floors were prepared with a bed of concrete, covered with several layers of cement; the last layer was carefully smoothed and levelled, and in this the cubes were fitted according to the pattern, and finally liquid cement was poured over the whole to fill in the cracks. When dry and hard the surface was[Pg 28] polished with sand and water rubbed on with little marble blocks.

Pavements of the best building period can be recognised by the size of the cubes, about three to the inch, and by the neatness and finish of the work. Two varieties of mosaic can be distinguished, that in which marbles, stones, and coloured glass are cut into cubes only and the so-called sectile mosaic in which elaborate scenes and groups of figures are represented, the coloured pieces being sawn into shapes to fit in with the design. The Tablinum in the house of the vestals and the temple of Jupiter on the Capitol were paved with sectile mosaic. The most brilliant mosaic which came into use during the Empire for the decoration of walls and vaults was made of fragments of coloured marble and glass, the latter specially prepared with acids to make it opaque and to give it a brilliant appearance. The art of mosaic work has never died out entirely in Rome. The Roman mosaic pavements and mosaic wall decoration were copied by the builders of mediæval churches, and even now a mosaic factory is kept up at the Vatican.

Although first used in this way, coloured marbles were gradually employed for the interior decoration of houses, for columns, dados, and friezes. Lucius Crassus, the consul (176 b.c.), was the first so to adorn his house, and Lucullus (151 b.c.) paved his hall with black marble. Later, entire rooms were lined with thin slabs clamped to the concrete wall with iron. Sometimes such marble walls were given a thin coat of stucco and[Pg 29] painted. As the passion for sumptuous interiors grew all the decorative arts were put into requisition. Walls were painted in fresco, as we can still see at Pompeii and in the house of Germanicus on the Palatine. Ceilings, walls, and cornices were ornamented in stucco in shallow relief. An extremely hard stucco was made with lime and powdered marble—it was nearly as durable as marble and could take almost as high a polish. It was even used for floors; for internal decoration, plaster of Paris was mixed with it. Mouldings, figures, arabesques, groups and scenes were worked in this stucco and delicately coloured. Examples have been preserved in the Diocletian museum and can be seen in situ in the Latin tombs.

The greatest plans for the building of Rome were conceived by Julius Caesar and Nero. Of Nero's buildings nothing remains except some ruins of his Golden House beneath the baths of Titus, while the designs of Caesar were destined to be carried out by his great successor Augustus. Justly could this emperor boast that he found Rome a city of brick and left it a city of marble. The republican period succeeding the expulsion of the Tarquins, and which his accession brought to a close, had not been so fruitful in public buildings as the epoch immediately following. Of the former, the Tabularium, the tombs of Bibulus and Cecilia Metella, the temple of Fortuna Virilis, and the ruins of the Fabrician bridge, the modern Ponte Quattro Capi, have come down to us. The city, however, was beginning to assume a more majestic appearance. On the accession of Augustus, the[Pg 30] Capitol was crowned by the Tarquins' temple to Jupiter, which was to be restored by Domitian. The valley between the Palatine and the Aventine was occupied by the enormous Circus Maximus, built by Tarquinius Priscus and decorated by Julius Caesar, and which has so entirely disappeared that we can only trace its site along the present Via dei Cerchi. The temples of Concord and Castor and Pollux stood upon the Forum Romanum, while the temple of Saturn bounding the steep Clivus Capitolinus which led upwards to the Capitol—the ancient Mons Saturninus—recorded the golden age when Saturn reigned in Italy.

The streets of the city were paved, and beyond the walls the immense Appian causeway crossed the Pontine marshes and stretched onwards towards Brindisi and the east.

In the forty years following Rome was transformed. There arose in the Campus Martius, the Pantheon with the baths and aqueduct of Agrippa, the portico of Octavia dedicated by Augustus to his sister, the theatre of Marcellus and the great mausoleum where the emperor and his kindred were to lie, and which, almost smothered in poor houses, has in modern times served the ignoble offices of a bull-ring and a third-rate theatre. Temples were restored, the Basilica Julia was completed, another Forum built with the temple of Mars Ultor in its midst. Upon the site of Augustus' birthplace on the Palatine hill a great palace was raised by himself and Tiberius, and this district of Rome became henceforth the abode of the Caesars.

THE COLOSSEUM ON A SPRING DAY

The Flavian amphitheatre, called Colosseum from the colossus or

colossal statue of Nero which stood on the velia before it. The

picture is taken from an orto belonging to the Barberini on the

Palatine, looking across the Arch of Constantine. See pages 22, 23,

31.

Augustus and his immediate successors were to witness the golden age of Roman building. After Hadrian came the period of decadence characterised by florid ornamentation, bad taste and workmanship, which culminated under Constantine and his sons.

Following in the steps of Augustus, Caligula and Nero erected palaces on the Palatine. Caligula connected the hill with the Forum, and Nero opened up an entrance towards the Caelian. Vespasian built there the Flavian house which his son Domitian was to dedicate as the Aedes Publica, a gift to the people. Septimius Severus extended the Palatine towards the south by the construction of his Septizonium.

Of the buildings of Tiberius, the columns of the temple of Ceres built into the church of S. Maria in Cosmedin remain to us; of those of Claudius, the beautiful ruined arches of his aqueduct. The Flavian emperors were great builders, and to this period belong the arch of Titus, built in a.d. 70 to commemorate the destruction of Jerusalem, a monument of Rome's best period, the ruined baths erected by this same emperor, and the great amphitheatre and ruins of the temple of Vespasian.

Trajan's great buildings—his forum and triumphal arch, his basilica and library—are represented by a very small excavated portion of the basilica, and the column whose summit marks the height of the hill cut away by this emperor to make a roadway between the Quirinal and Capitol and thus relieve the congested traffic of the city.[Pg 32]

The only fragments left of the work of Hadrian are the ruins of a villa near Tivoli, the mausoleum and Pons Aelius, now the castle and bridge of S. Angelo; and behind the church of S. Francesca Romana in the Forum the ruins of the Templum Urbis, the temple of Venus and Rome, with its twin niches for the gods, one turned towards the convent the other looking outwards towards the Colosseum. The gilt bronze tiles from the roof of this temple were removed by Pope Honorius I. to deck the Christian Templum Urbis S. Peter's.

During the following 140 years there arose in Rome, amongst other monuments that have perished, the temple of Antoninus and Faustina built by Antoninus Pius in memory of his wife and now transformed into the church of S. Lorenzo in Miranda, the column of Marcus Aurelius, the triumphal arch of Septimius Severus dedicated to his sons Caracalla and Geta, the baths which bear this eldest son's name, although only begun by him and completed by Heliogabalus and Alexander Severus, the walls of Aurelian which still encompass the city and the thermae of Diocletian. The latest of the imperial buildings were the temple built by Maxentius to his son Romulus, now the church of SS. Cosma and Damian in the Forum, and the baths, basilica, and triumphal arch of Constantine.

A visitor to this city of the Cæsars must have been almost bewildered by what he saw. As he passes through the town great buildings meet his glance on every side, their gilded tiles and white marble walls[Pg 33] glistening in the sun and clear atmosphere. Crowds jostle him in the narrow paved roads. He crosses one Forum after another, six in all, and finally reaches the Campus Martius. He pauses upon the steps of temples and basilicas which seem on all sides to surround these busy centres of Roman life. Open spaces are crowded with trees and shrubs, fountains and statues. He can count thirty-six triumphal arches and eight bridges that span the yellow Tiber. He passes theatres and stadia for races and games, columns and obelisks. Occasionally he comes across a giant building, a colossus even in that city of marvels, the amphitheatre of Vespasian or the thermae of Diocletian, or an immense circus where 285,000 spectators are seated waiting for the chariot races to begin; he has noticed groups of charioteers in their distinctive colours, and heavy betting is going on. He has walked from one end of the city to the other sheltered from sun and rain, along covered porticoes, their pavements rich mosaics, and their length decorated throughout with a continuous series of statues and pictures. He has gazed upon the stupendous palaces of the Palatine, and has noticed the streams of people passing in and out of the city gates on their way to the suburbs which extend to Veii Tivoli and Ostia, or to the villas, parks and gardens, villages and farms, which cover the outskirts of Rome to a distance of 15 miles, amongst which great roads lined by marble tombs radiate outwards towards the hills.

With the decay of this mighty city began the era of church building. The origin of the Christian basilica is[Pg 34] still a matter of controversy, but the results of careful and recent research[1] go to confirm the view that it was modelled not upon its Pagan namesake the forensic basilica, but upon the private hall found in many of the dwellings of rich Romans of consular or senatorial rank which served for those domestic tribunals for the adjudication of family disputes sanctioned by Roman law. This conclusion has been overlooked from a mistaken belief that the first Christians were recruited from the slaves and poorer classes of the population, but it is now proved that noble Romans and even members of Imperial families early embraced Christianity, and it was more than probable that the domestic basilicas in their houses should be utilised as places of assembly by members of their faith, the gathering of a large body of persons being concealed during times of persecution, by the use of the many entrances common to the Roman house.

The domestic basilica dedicated as a place of Christian assembly, became with the development of the ecclesiastical system, the Roman titulus, the church in the house, and as no public hall was built until after the Peace of the church, these were multiplied as the Christian population grew and numbered 40 by the second century. The Christian basilica was thus in existence and perfected in all its liturgical parts in the first three centuries, and when Constantine built his great extramural churches, he only amplified a type familiar to every Christian.

THE COLOSSEUM AT SUNSET

Taken from the Mons Oppius, one of the two spurs of the Esquiline

hill. See pages 5, 11.

S. Maria Maggiore probably existed as a domestic[Pg 35] basilica at a time anterior to that of its reputed founders Liberius and Sixtus, and we know that S. Croce and the Lateran were constructed within the Sessorian palace and the house of the Laterani of which they probably formed the halls.

Architecturally also the earliest churches resembled more nearly the domestic hall than the public basilica. The latter were little more than a covered portion of the Forum upon which they stood. They were entered from either side through the open ambulatories which as we have seen were free to all. The extremities were walled up later and prolonged into an apse to increase the space available for legal purposes. The domestic basilica on the other hand was a rectangular building roofed and closed on all sides, its single apse at one extremity facing the main entrance. The central space was surrounded on three sides by porticoes dividing it into portions which became the aisles for the worshippers and the narthex for the use of catechumens. The domestic judge's seat standing in the apse was replaced by the bishop's throne, and the cancellum became the chancel rail dividing this portion, the presbytery of the church, from the rest of the building.

The ruins of the Flavian basilica in Domitian's house on the Palatine (81-96) affords us a ground plan of such a domestic hall, in this instance placed close to the triclinium of the house and not in a direct line with the vestibulum or entrance as was generally the case. Here a fragment of the cancellum can still be seen in situ.

The Christian altar of the earliest churches placed in[Pg 36] front of the apse, faced the congregation, and a space before it, beyond the depressed portion or confessio, was reserved for the choir and was surrounded by a marble balustrade. The columns supported a horizontal architrave, above it a flat wall pierced with windows and the plain roof of cedar-wood beams.

The floors were paved with a fine mosaic of marble and green serpentine alternating with slabs of white marble or discs of red porphyry. Tribune, arch, and vault, and sometimes other portions of the walls, were decorated with brilliant mosaics and examples of this work, of the fourth, sixth, ninth, and twelfth centuries, and possibly of the second or third, have happily escaped the ravishing hand of the restorer. In the twelfth century the art of marble working underwent a temporary revival under the influence of a talented family of artists, the Cosmati; and a good deal of their work and that of their school is still to be found in Rome, the carved marble and an inlay of mosaic upon marble being easily recognisable in the decoration of the cloisters of the Lateran and of S. Paul's outside the walls, upon ambones, candelabra, and tombs scattered throughout the churches.

The straight architectural lines of the Christian basilicas and their subdued colouring of floor and apse produce a delicate and harmonious effect, but they were erected during a debased building period and were not designed for strength, and only a few have weathered the storms of the middle ages and escaped destruction beneath the tasteless restorations of the Renaissance.[Pg 37]

The new building epoch born in Rome was to be nourished entirely at the expense of the old. Columns and mouldings were transferred bodily from the nearest basilica to furnish the Christian church, and were there arranged haphazard. Simpler still, walls of ancient bricks were quickly run up between the solid columns of a temple; marble casings were torn off to be used as common building stone; statues, carved cornices, and friezes were thrust into lime-kilns which sprang up all over the city wherever the ancient monuments stood thickest; priceless marbles were ground into fragments for making mosaics or were mixed with cement and made into concrete.

When Constantine left Rome to found his new capital the city had already degenerated into a squalid provincial town, and fifty years later Jerome could refer to its gilded squalor and its temples lined with cobweb.

Already the seal had been put upon the old order when Gratian in 383 abolished the privileges of the pagan places of worship, and quickly disaster followed upon the heels of destruction. Twice Alaric despoiled the city and carried off priceless booty. Vitiges tore the marble from the mausoleum of Hadrian and destroyed the aqueducts; Genseric dismantled the temple of Jupiter; Robert Guiscard laid waste the Campus Martius and other parts of the city by fire. Sieges, sacks, earthquakes, fires, and inundations succeeded each other until the old level of the city was in places buried 50 feet beneath accumulated ruin and rubbish.[Pg 38]

The scene shifts once more; centuries have slipped by and the city of Rome has become a desolation. Marble columns and granite obelisks lie prone upon the ground, and many more have found graves beneath the soil. Enormous mounds of earth and masonry, disfigured with rude battlements, represent all that is left of the great monuments; crumbling ruins and waste land stretch away to the walls, and without the campagna has become a fever-stricken wilderness.

Military fortresses, watch-towers on the walls, and bell-towers of churches are the only buildings kept in repair. Gaunt wolves snarl and fight over the refuse heaps under the walls of S. Peter's. A gibbet crowns the bare summit of the Capitol, goatherds pasture their flocks on its sides and along the green slopes of the Forum, and thus the hill and the tract of land at its foot have returned once more to their primitive pastoral state and their pastoral names, the "hill of goats" and the "field of cows." Over all broods the ominous silence of terror, bloodshed, and pestilence.

Upon this scene of ruin the Renaissance and modern city of Rome was to come into being, and the mediaeval buildings were in their turn to be destroyed or overlaid with a modern garb, leaving only a few churches and convents, a few towers and palaces, a few cloisters to mark the passing of the centuries.

ARCH OF TITUS

Erected to commemorate this Emperor's destruction of Jerusalem, a.d.

70. It is decorated with reliefs of the seven-branched candlestick and

other spoils of the Temple which were carried through the city in the

Emperor's triumph. See page 31.

The remains of the imperial city are described by a modern writer[2] lying like a skeleton beneath the modern town, beneath streets, villas, and public buildings;[Pg 39] and from the fifteenth century, when Rome, which had only just escaped an extinction as complete as that of her neighbour and ancient rival Tusculum, began once more to rise from the dust, to modern times, all the building materials have been furnished by her ruins. The few monuments that have been preserved owe their safety to their consecration as churches.

Of all the despoilers to which Rome has fallen a victim, none have been so assiduous in their destruction as her own rulers and people. Streets have been paved with building stone, churches and palaces built with ancient materials. Monuments of the utmost artistic and historic value have been destroyed for the purpose, the Colosseum alone being robbed of 2522 cart-loads of travertine in the fifteenth century. The inadequate prohibitions issued at rare intervals proved impotent in presence of a practice so deep rooted and time honoured. Every villa garden and palace staircase is peopled with ancient statues. Fragments of inscriptions, of carved mouldings and cornices, marble pillars and antique fountains, are met with in every courtyard. Even a humble house or shop will have a marble step or a marble lintel to the front door. To the present day no piece of work is ever undertaken in Rome, no house foundation dug or gas-pipe laid, but the workmen come across some ancient masonry, an aqueduct whose underground course is unknown and unexplored, a branch of one of the great cloacae, or the immense concrete vault of a bath or temple whose destruction gives as much trouble as if it were solid rock.[Pg 40]

Fortunately for the student and the archaeologist a government official, a "custodian of excavations," now watches all such operations, and all "finds" of importance, fragments of inscriptions and statues, earthenware lamps, bronze or glass vessels, fragments of mosaic, and gold ornaments, are collected and reported.

From the catacombs, the subterranean burial-places of the first Roman Christians, to the basilica of S. Peter's, the greatest ecclesiastical building on earth, there is no break in the drama of history. When you come out from the cemetery of Callistus, on to the fields bordering the Appian Way, and look across to the dome of the great church commemorating Peter, you say to yourself "That is the interpretation of this": this may see in its own humble features the lineaments of that; the church which dominates the Roman country—in imperial possession of Rome—may recognise that the silent underground galleries of the Appia had already taken as effective a possession of the capital of the world.

The Roman Church is founded upon three events: the apostolic preaching, the constancy of its martyrs, its position as the heir of Imperial Rome—a position early figured and represented in the persons of its bishops. All these things have their monument in the catacombs; which bear indisputable traces of the sojourn[Pg 42] and the preaching of the Apostles, which are the earliest shrines of the Roman martyrs, and which preserve for us in the crypt in the cemetery of Callistus, set apart for the leaders of the Roman Church from Antheros to Eutychian (a.d. 235-275),[3] the veritable nucleus of papal domination. It was the successors of these men who were to fill the rôle left vacant by Constantine's departure for Byzantium; to be forced into a position of overlordship through the uncertainty of the emperor's government by lieutenants—first in Rome and then in Italy; to consolidate this power by constant accretions of Italian territory, and, finally, to acquire by spiritual conquest a universal suzerainty as real as that of the Roman emperor. If those who inscribed the proud words round the dome of S. Peter's had known that hidden in the catacombs there were frescoes representing Peter as the new Moses striking the rock from which flow forth the saving waters of Christ—the name Petrus clearly written above him—even they must have thrilled with wonder and awe: the upholders of Petrine primacy could not have imagined or devised a parable of the first centuries better fitted to their hand.

A PROCESSION IN THE CATACOMB OF CALLISTUS

The nucleus of the great catacomb on the Via Appia was formed by the

crypts of Lucina and the hypogaeum of the family of the Caecilii,

both pagan and Christian members of which had their burial places on

the Appian Way. S. Cecilia was buried here. See pages 42, 45, 46, 29.

The burial-places of the first Christians in Rome were their only certain property. The law allowed to every corporation its religiosus locus, its God's acre, property seldom confiscated even in the worst hours of the great persecutions. It was thus that the Christians,[Pg 43] though they never lived in the catacombs, came to regard them as retreats, as places where it was safe to meet for prayer, for mutual encouragement, even for the catechising of neophytes and children. Round them were their dead, their loved ones, nay, round them were their martyrs, the men and women who were to prove that "the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church"; whose heroic deaths had been witnessed by many; the memory of whose heroism was to prove almost as potent as ocular witness when their burial-places became the nuclei of the first Christian churches, and the abounding reverence felt for them inaugurated the Christian cult of the saints.

The catacombs lie for the most part within a three mile radius of the wall of Aurelian. They number forty-five, and it is calculated that the passages, galleries, and chambers of which they consist cover several hundred miles, forming a vast underground city—"subterranean Rome." For the first 300 years, until "the Peace of the Church," this was the ordinary place of burial, certain catacombs being affiliated, from the third century, to the ecclesiastical regions in the city. Even after the "Peace" Christians were sometimes buried here, until the fifth century, after which the catacombs were visited as places of pilgrimage for another 400 years.

From the ninth century they fell into complete neglect; no one visited these sanctuaries of the sufferings, these monuments of the human affections and religious beliefs of the first Christians. Visitors heard that Rome[Pg 44] was built upon terrible underground chasms, filled with snakes, some part of which was every now and then revealed to the terrified inhabitants. No one penetrated till the fifteenth century—the first pioneer belongs to the sixteenth—and it was not till the second half of the nineteenth that a new world was laid bare to the student by the excavations of De Rossi, who rediscovered the great cemetery of Callistus, containing the now famous "papal crypt," and whose labours have resulted in restoring to us nearly twenty catacombs.

The terrible underground chasms filled with snakes were found to be galleries of tombs, crypts of all sizes, lighted by shafts, some with seats for catechists, some adapted as miniature basilicas, decorated with frescoes recording biblical scenes, New Testament parables and symbolical representations of New Testament events—(in which the "apocrypha" is not distinguished from the "canon," and the history of Susanna and the Elders sustained the faith and comforted the courage of Christians by the side of the scene of Moses striking the rock or Christ feeding His disciples); eloquent with inscriptions in the epigraphy of the first four centuries, recorded in moments of simple human emotion, intended only for the dead and those who survived them sorrowing; and lastly, covered with graffiti, with prayers, names, acclamations, scratched on the walls of galleries leading to some favourite crypt by pilgrim visitors in later centuries.

In this hidden and quiet place of the dead there is recorded a revolution parallel to a volcanic upheaval of[Pg 45] nature. Here we have a permanent record of the meeting of classical Rome with Judaea and Christianity; here the graceful art of Pompeii meets the imagery of the Hebrew bible; here the Flavii met the Jews of the Dispersion; here as in a Titanic workshop, Rome, taking its religion from the Jew, moulded the faith which the Chosen People had discarded into the greatest religious organisation on earth—Catholic Christianity.

The two arch-cemeteries are those of Callistus on the Via Appia and Priscilla on the Salaria. They are arch-cemeteries because their origin and the part they played in the early years of Roman Christianity gave them a pre-eminent importance, and having been bestowed upon the Church by their owners they became the official catacombs of the Christian community. Each bears in its bosom the record of the first Roman converts; each is rich in frescoes and inscriptions; each bears testimony to the fact that from the beginning the Roman Christians counted among them many of patrician and senatorial rank; we meet with the names of the Aurelii, Caecilii, Maximi Caecilii, of Praetextatus Caecilianus and Pomponius Grecinus, and of Cornelius, the first bishop to belong to a Roman gens, in the catacomb of Callistus; and with those of the Prisci, Ulpii, and Acilii Glabriones in that of Priscilla. Priscilla, with her son the Senator Pudens, is the reputed hostess of Peter on his visit to Rome, and in the catacomb which bears her name there occurs repeatedly the Apostle's name—unknown in classical nomenclature—both in its Greek and Latin forms, Petros, Petrus. It is a region[Pg 46] of this catacomb which preserves the tradition of the Fons sancti Petri, "the well or font of S. Peter," "the cemetery where Peter baptized" or "where Peter first sat," still unconsciously recorded in the Roman feast of "the Chair of S. Peter" on January 18. Here too was buried the philosopher Justin, martyred under Aurelius in a.d. 165, who lived in the house of Pudens, and here, when Justin was describing the rite itself in his Apology to the emperors, was frescoed the earliest representation of the solemn moment of the breaking of bread at the Eucharist. The mystical number of the guests, seven, the fish on the table, archaic symbol of Christ, the "seven baskets full" in allusion to the miracle of the loaves, and the fact that the agapê was already dissociated from the Eucharist in the time of Justin, mark this out as a typical example of that symbolical treatment of real events which is characteristic of early Christian art. The celebrant stands at one corner of the crescent-shaped table breaking the bread; five men and women sit at the table, the only other standing figure being that of a woman wearing the Jewish married woman's bonnet, filling, apparently, the office of vidua or woman-elder. The catacomb of Callistus—an agglomeration of separate hypogaea, which originated in the crypts of Lucina and the cemetery of those Caecilii who were among the earliest Roman families to embrace Christianity—is no less interesting.

The unique interest of these monuments lies in the fact that they are the incorruptible record of the sentiments,[Pg 47] affections, and beliefs of the first Christians. In these frescoes and inscriptions no forgeries or interpolations could creep, no P1 and P2, no "Elohist" or "Jahvist" could confuse the issues and mystify the interpretation. The untouched story appeals to us in mute eloquence.