More Misrepresentative Men

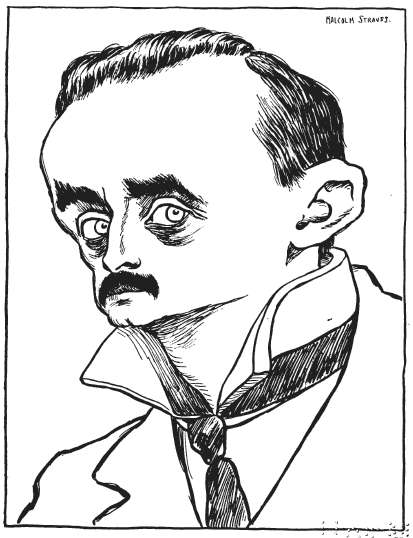

Harry Graham

More Misrepresentative Men

By Harry Graham

Author of

"Ruthless Rhymes for Heartless Homes,"

"Misrepresentative Men,"

"Ballads of the Boer War,"

"Verse and Worse," etc., etc.

PICTURES BY

Malcolm Strauss

NEW YORK

Fox, Duffield & Company

MCMV

Copyright, 1905, by

FOX, DUFFIELD & COMPANY

Published in September, 1905

To

E. B.

[7]

Contents

| PAGE | |

| Author's Foreword | 9 |

| Publisher's Preface | 14 |

| Robert Burns | 18 |

| William Waldorf Astor | 33 |

| Henry VIII | 42 |

| Alton B. Parker | 48 |

| Euclid | 54 |

| J. M. Barrie | 65 |

| Omar Khayyam | 72 |

| Andrew Carnegie | 78 |

| King Cophetua | 85 |

| Joseph F. Smith | 90 |

| Sherlock Holmes | 98 |

| Aftword | 109 |

[8]

List of Illustrations

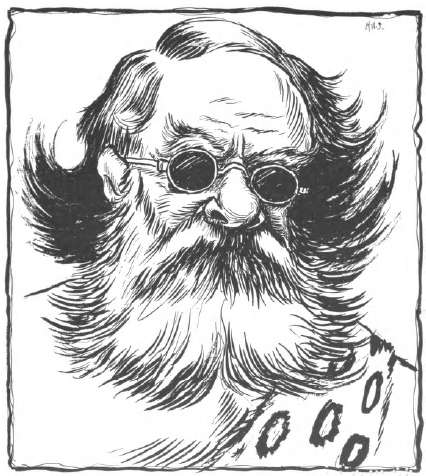

| Andrew Carnegie | FRONTISPIECE |

| FACING PAGE |

|

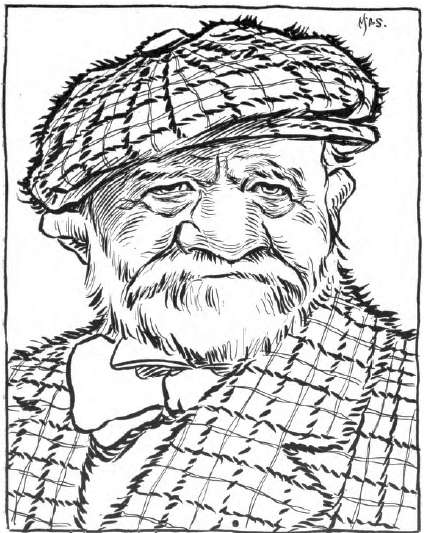

| Robert Burns | 18 |

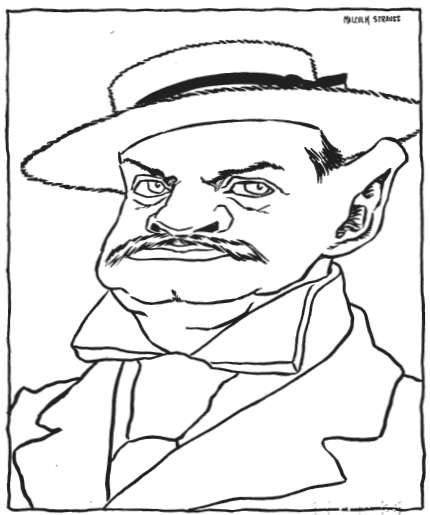

| William Waldorf Astor | 34 |

| Henry VIII | 42 |

| Alton B. Parker | 48 |

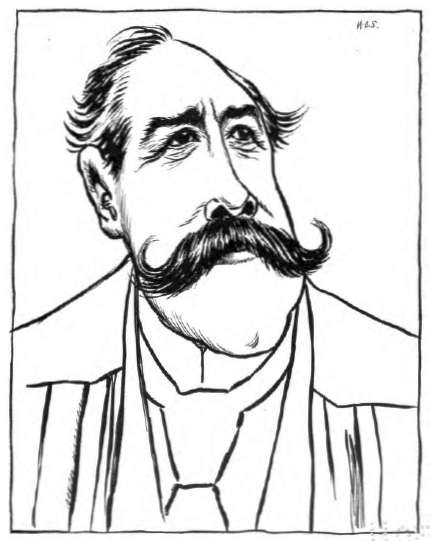

| Euclid | 54 |

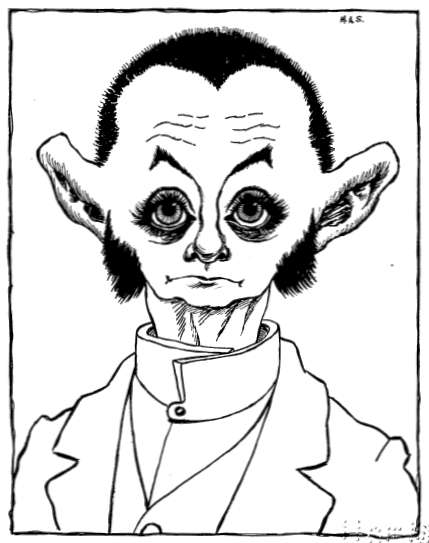

| J. M. Barrie | 66 |

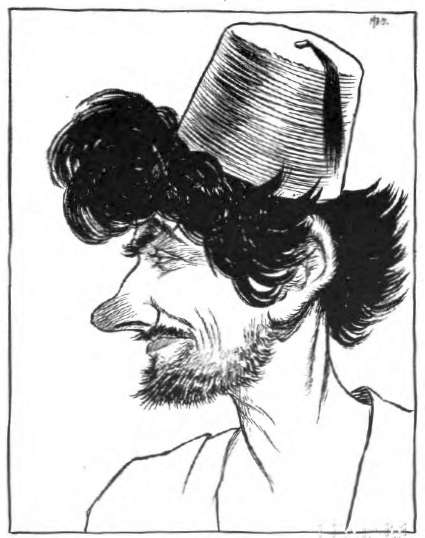

| Omar Khayyam | 72 |

| King Cophetua | 86 |

| Joseph F. Smith | 90 |

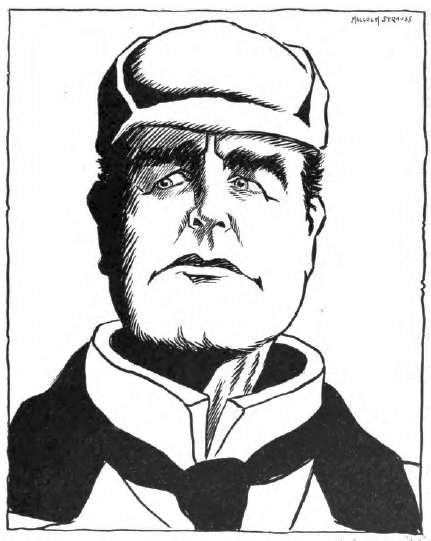

| Sherlock Holmes | 98 |

[9]

Authors Foreword

(To the Publisher)

HEN honest men are all in bed,

We poets at our desks are toiling,

To earn a modicum of bread,

And keep the pot a-boiling;

We weld together, bit by bit,We poets at our desks are toiling,

To earn a modicum of bread,

And keep the pot a-boiling;

The fabric of our laboured wit.

[10]

We see with eyes of frank dismay

The coming of this Autumn season,

When bards are driven to display

Their feast of rhyme and reason;

With hectic brain and loosened collar,

We chase the too-elusive dollar.

The coming of this Autumn season,

When bards are driven to display

Their feast of rhyme and reason;

With hectic brain and loosened collar,

We chase the too-elusive dollar.

While Publishers, in search of grist,

Despise our masterly inaction,

And shake their faces in our fist,

Demanding satisfaction,

We view with vague or vacant mind

The grim agreements we have signed.

[11]

Despise our masterly inaction,

And shake their faces in our fist,

Demanding satisfaction,

We view with vague or vacant mind

The grim agreements we have signed.

[11]

For though a willing public gives

Its timely share of cash assistance,

The author (like the dentist) lives

A hand-to-mouth existence;

And Publishers, those modern Circes,

Make pig's-ear purses of his verses.

Its timely share of cash assistance,

The author (like the dentist) lives

A hand-to-mouth existence;

And Publishers, those modern Circes,

Make pig's-ear purses of his verses.

Behold! How ill, how thin and pale,

The features of the furtive jester!

Compelled by contracts to curtail

His moments of siesta!

A true White Knight is he to-day

(Nuit Blanche, as Stevenson would say).[12]

The features of the furtive jester!

Compelled by contracts to curtail

His moments of siesta!

A true White Knight is he to-day

(Nuit Blanche, as Stevenson would say).[12]

Ah, surely he has laboured well,

Constructing this immortal sequel,—

A work which no one could excel,

And very few can equal,—

A volume which, I dare to say,

Is epoch-making, in its way.

Constructing this immortal sequel,—

A work which no one could excel,

And very few can equal,—

A volume which, I dare to say,

Is epoch-making, in its way.

When other poets' work is not,

These verses shall retain their label;

When Herford is a thing forgot,

And Ade an ancient fable;

When Goops no longer give a sign

Of Burgess's empurpled kine.[13]

These verses shall retain their label;

When Herford is a thing forgot,

And Ade an ancient fable;

When Goops no longer give a sign

Of Burgess's empurpled kine.[13]

My Publishers, I love you so!

Your well-secreted virtues viewing;

Who never let your right hand know

Whom your left hand is doing;

Who hold me firmly in your grip,

And crack your cheque-book, like a whip!

Your well-secreted virtues viewing;

Who never let your right hand know

Whom your left hand is doing;

Who hold me firmly in your grip,

And crack your cheque-book, like a whip!

My Publishers, make no mistake,

You have in me an avis rara,

So write a princely cheque, and make

It payable to bearer;

I love you, as I said before,

But oh! I love your money more!

[14]

You have in me an avis rara,

So write a princely cheque, and make

It payable to bearer;

I love you, as I said before,

But oh! I love your money more!

[14]

Publisher's Preface

(To the Author)

ORACIOUS Author, gorged with gold,

Your grasping greed shall not avail!

In vain you venture to unfold

Your false prehensile tale!

I view in scorn (unmixed with awe)Your grasping greed shall not avail!

In vain you venture to unfold

Your false prehensile tale!

The width of your capacious maw.[15]

On me the onus has to fall

Of your malevolent effusions;

'Tis I who bear the brunt of all

Your libellous allusions;

To bolster up your turgid verse,

I jeopardise my very purse!

Of your malevolent effusions;

'Tis I who bear the brunt of all

Your libellous allusions;

To bolster up your turgid verse,

I jeopardise my very purse!

You do not hesitate to fleece

The Publisher you scorn to thank,

And when you manage to decrease

His balance at the bank,

Your face is lighted up with greed,

And you are lantern-jawed indeed![16]

The Publisher you scorn to thank,

And when you manage to decrease

His balance at the bank,

Your face is lighted up with greed,

And you are lantern-jawed indeed![16]

Yet will I still heap coals of fire,

Until your coiffure is imbedded,

And you at last, perchance, shall tire

Of growing so hot-headed,

And realise that being funny

Is not a mere affair of money.

Until your coiffure is imbedded,

And you at last, perchance, shall tire

Of growing so hot-headed,

And realise that being funny

Is not a mere affair of money.

And so, in honour of your pow'rs,

A fragrant bouquet will I pick,

Of rare exotics, blossoms, flow'rs

Of speech and rhetoric;

I'll add a thistle, if I may,

And, round the whole, a wreath of bay.[17]

A fragrant bouquet will I pick,

Of rare exotics, blossoms, flow'rs

Of speech and rhetoric;

I'll add a thistle, if I may,

And, round the whole, a wreath of bay.[17]

The blossoms for your button-hole,

To mark your affluent condition,

Exotics to inspire your soul

To further composition.

Come, set the bays upon your brow!

* * * * *

Well, eat the thistle, anyhow!

[18]

To mark your affluent condition,

Exotics to inspire your soul

To further composition.

Come, set the bays upon your brow!

* * * * *

Well, eat the thistle, anyhow!

[18]

Robert Burns

HE jingling rhymes of Dr. Watts

Excite the reader's just impatience,

He wearies of Sir Walter Scott's

Melodious verbal collocations,

And with advancing years he learns

To love the simpler style of Burns.

Excite the reader's just impatience,

He wearies of Sir Walter Scott's

Melodious verbal collocations,

And with advancing years he learns

To love the simpler style of Burns.

[19]

Too much the careworn critic knows

Of that obscure robustious diction,

Which like a form of fungus grows

Amid the Kailyard school of fiction;

In Crockett's cryptic caves one sighs

For Burns's clear and spacious skies.

Of that obscure robustious diction,

Which like a form of fungus grows

Amid the Kailyard school of fiction;

In Crockett's cryptic caves one sighs

For Burns's clear and spacious skies.

Tho' no aspersions need be cast

On Barrie's wealth of wit fantastic,

Creator of that unsurpass'd

If most minute ecclesiastic;

Yet even here the eye discerns

No master-hand like that of Burns.[20]

On Barrie's wealth of wit fantastic,

Creator of that unsurpass'd

If most minute ecclesiastic;

Yet even here the eye discerns

No master-hand like that of Burns.[20]

The works of Campbell and the rest

Exhale a sanctimonious odour,

Their vintage is but Schnapps, at best,

Their Scotch is simply Scotch-and-sodour!

They cannot hope, like Burns, to win

That "touch which makes the whole world kin."

Exhale a sanctimonious odour,

Their vintage is but Schnapps, at best,

Their Scotch is simply Scotch-and-sodour!

They cannot hope, like Burns, to win

That "touch which makes the whole world kin."

Tho' some may sing of Neil Munro,

And virtues in Maclaren see,

Or want but little here below,

And want that little Lang, maybe;

Each renegade at length returns,

To praise the peerless pow'rs of Burns.[21]

And virtues in Maclaren see,

Or want but little here below,

And want that little Lang, maybe;

Each renegade at length returns,

To praise the peerless pow'rs of Burns.[21]

His verse, as all the world declares,

And Tennyson himself confesses,

The radiance of the dewdrop shares,

The berry's perfect shape possesses;

And even William Wordsworth praises

The magic of his faultless phrases.

And Tennyson himself confesses,

The radiance of the dewdrop shares,

The berry's perfect shape possesses;

And even William Wordsworth praises

The magic of his faultless phrases.

But he, whose books bedeck our shelves,

Whose lofty genius we adore so,

Was only human, like ourselves,—

Perhaps, indeed, a trifle more so!

And joined a thirst that nought could quench

To morals which were frankly French.[22]

Whose lofty genius we adore so,

Was only human, like ourselves,—

Perhaps, indeed, a trifle more so!

And joined a thirst that nought could quench

To morals which were frankly French.[22]

And ev'ry night he made his way,

With boon companions, bent on frolic,

To inns of ill-repute, where lay

Refreshments—chiefly alcoholic!

(But I decline to raise your gorges,

Describing these nocturnal orgies.)

With boon companions, bent on frolic,

To inns of ill-repute, where lay

Refreshments—chiefly alcoholic!

(But I decline to raise your gorges,

Describing these nocturnal orgies.)

Of love-affairs he knew no end,

So long and ardently he flirted,

And e'en the least suspicious friend

Would feel a trifle disconcerted,

When Burns was sitting with his "sposa,"

"As thick as thieves on Vallombrosa!"[23]

So long and ardently he flirted,

And e'en the least suspicious friend

Would feel a trifle disconcerted,

When Burns was sitting with his "sposa,"

"As thick as thieves on Vallombrosa!"[23]

A Cockney Chiel who found him thus,

And showed some conjugal alarm,

When Burns implored him not to fuss,

Enquiring calmly, "Where's the harm?"

Replied at once, with perfect taste,

"The harm is round my consort's waist!"

And showed some conjugal alarm,

When Burns implored him not to fuss,

Enquiring calmly, "Where's the harm?"

Replied at once, with perfect taste,

"The harm is round my consort's waist!"

"A poor thing but my own," said he,

His fair but fickle bride denoting,

And she, with scathing repartee,

Assented, wilfully misquoting,

(Tho' carefully brought up, like Jonah),

"A poorer thing—and yet my owner!"[24]

His fair but fickle bride denoting,

And she, with scathing repartee,

Assented, wilfully misquoting,

(Tho' carefully brought up, like Jonah),

"A poorer thing—and yet my owner!"[24]

The most bucolic hearts were burnt

By Burns' amatory glances;

The most suburban spinsters learnt

To welcome his abrupt advances;

When Burns was on his knee, 'twas said,

They wished that they were there instead!

By Burns' amatory glances;

The most suburban spinsters learnt

To welcome his abrupt advances;

When Burns was on his knee, 'twas said,

They wished that they were there instead!

They loved him from the first, in spite

Of angry parents' interference;

They deemed his courtship so polite,

So captivating his appearance;

So great his charm, so apt his wit,

In local parlance, Burns was IT![25]

Of angry parents' interference;

They deemed his courtship so polite,

So captivating his appearance;

So great his charm, so apt his wit,

In local parlance, Burns was IT![25]

The rustic maids from far and wide,

Encouraged his unwise flirtations;

For love of Burns they moped and sighed,

And, while their nearest male relations

Were up in arms, the sad thing is

That they themselves were up in his!

Encouraged his unwise flirtations;

For love of Burns they moped and sighed,

And, while their nearest male relations

Were up in arms, the sad thing is

That they themselves were up in his!

His crest a mug, with open lid,

The kind in vogue with ancient Druids,—

Inscribed "Amari Aliquid,"

(Which means "I'm very fond of fluids!"),

On either side, as meet supporters,

The village blacksmith's lovely daughters.[26]

The kind in vogue with ancient Druids,—

Inscribed "Amari Aliquid,"

(Which means "I'm very fond of fluids!"),

On either side, as meet supporters,

The village blacksmith's lovely daughters.[26]

"Men were deceivers ever!" True,

As Shakespeare says (Hey Nonny! Nonny!),

But one should always keep in view

That "tout comprendr' c'est tout pardonny";

In judging poets it suffices

To scan their verses, not their vices.

. . . . . .

The poets of the present time

Attempt their feeble imitations;

Are economical of rhyme,

And lavish with reiterations;[27]

The while a patient public swallows

A "Border Ballad" much as follows:—

As Shakespeare says (Hey Nonny! Nonny!),

But one should always keep in view

That "tout comprendr' c'est tout pardonny";

In judging poets it suffices

To scan their verses, not their vices.

. . . . . .

The poets of the present time

Attempt their feeble imitations;

Are economical of rhyme,

And lavish with reiterations;[27]

The while a patient public swallows

A "Border Ballad" much as follows:—

Jamie lad, I lo'e ye weel,

Jamie lad, I lo'e nae ither,

Jamie lad, I lo'e ye weel,

Like a mither.

Jamie lad, I lo'e nae ither,

Jamie lad, I lo'e ye weel,

Like a mither.

Jamie's ganging doon the burn,

Jamie's ganging doon, whateffer,

Jamie's ganging doon the burn,

To Strathpeffer!

Jamie's ganging doon, whateffer,

Jamie's ganging doon the burn,

To Strathpeffer!

Jamie's comin' hame to dee,

Jamie's comin' hame, I'm thinkin',[28]

Jamie's comin' hame to dee,

Dee o' drinkin'!

Jamie's comin' hame, I'm thinkin',[28]

Jamie's comin' hame to dee,

Dee o' drinkin'!

Hech! Jamie! Losh! Jamie!

Dinna greet sae sair!

Gin ye canna, winna, shanna

See yer lassie mair!

Wha' hoo!

Wha' hae!

Strathpeffer!

Dinna greet sae sair!

Gin ye canna, winna, shanna

See yer lassie mair!

Wha' hoo!

Wha' hae!

Strathpeffer!

I give you now, as antidote,

Some lines which I myself indited.[29]

Carnegie, when he read them, wrote

To say that he was quite delighted;

Their pathos cut him to the quick,

Their humour almost made him sick.

Some lines which I myself indited.[29]

Carnegie, when he read them, wrote

To say that he was quite delighted;

Their pathos cut him to the quick,

Their humour almost made him sick.

The queys are moopin' i' the mirk,

An' gin ye thole ahin' the kirk,

I'll gar ye tocher hame fra' work,

Sae straught an' primsie;

In vain the lavrock leaves the snaw,

The sonsie cowslips blithely blaw,

The elbucks wheep adoon the shaw,

Or warl a whimsy.[30]

The cootie muircocks crousely craw,

The maukins tak' their fud fu' braw,

I gie their wames a random paw,

For a' they're skilpy;

For wha' sae glaikit, gleg an' din,

To but the ben, or loup the linn,

Or scraw aboon the tirlin'-pin

Sae frae an' gilpie?

An' gin ye thole ahin' the kirk,

I'll gar ye tocher hame fra' work,

Sae straught an' primsie;

In vain the lavrock leaves the snaw,

The sonsie cowslips blithely blaw,

The elbucks wheep adoon the shaw,

Or warl a whimsy.[30]

The cootie muircocks crousely craw,

The maukins tak' their fud fu' braw,

I gie their wames a random paw,

For a' they're skilpy;

For wha' sae glaikit, gleg an' din,

To but the ben, or loup the linn,

Or scraw aboon the tirlin'-pin

Sae frae an' gilpie?

Och, snood the sporran roun' ma lap,

The cairngorm clap in ilka cap,

Och, hand me o'er

Ma lang claymore,

[31] Twa, bannocks an' a bap,

Wha hoo!

Twa bannocks an' a bap!

. . . . . .

O fellow Scotsman, near and far,

Renowned for health and good digestion,

For all that makes you what you are,—

(But are you really? That's the question)—

Be grateful, while the world endures,

That Burns was countryman of yours.

The cairngorm clap in ilka cap,

Och, hand me o'er

Ma lang claymore,

[31] Twa, bannocks an' a bap,

Wha hoo!

Twa bannocks an' a bap!

. . . . . .

O fellow Scotsman, near and far,

Renowned for health and good digestion,

For all that makes you what you are,—

(But are you really? That's the question)—

Be grateful, while the world endures,

That Burns was countryman of yours.

And hand-in-hand, in alien land,

Foregather with your fellow cronies,[32]

To masticate the haggis (cann'd)

At Scottish Conversaziones,

Where, flushed with wine and Auld Lang Syne,

You worship at your country's shrine!

[33]

Foregather with your fellow cronies,[32]

To masticate the haggis (cann'd)

At Scottish Conversaziones,

Where, flushed with wine and Auld Lang Syne,

You worship at your country's shrine!

[33]

William Waldorf Astor

OW blest a thing it is to die

For Country's sake, as bards have sung!

(To quote the vulgar Latin tongue);

And yet to him the palm we give

Who for his fatherland can live.[34]

Historians have explained to us,

In terms that never can grow cold,

How well the bold Horatius

Played bridge in the brave days of old;

And we can read of hosts of others,

From Spartan boys to Roman mothers.

In terms that never can grow cold,

How well the bold Horatius

Played bridge in the brave days of old;

And we can read of hosts of others,

From Spartan boys to Roman mothers.

But nowhere has the student got,

From poet, pedagogue, or pastor,

The picture of a patriot

So truly typical as Astor;

And none has ever shown a greater

Affection for his Alma Mater.

From poet, pedagogue, or pastor,

The picture of a patriot

So truly typical as Astor;

And none has ever shown a greater

Affection for his Alma Mater.

[35]

With loyalty to Fatherland

His heart inflexible as starch is,

Whene'er he hears upon a band

The too prolific Sousa's marches;

And from his eyes a tear he wipes,

Each time he sees the Stars and Stripes.

His heart inflexible as starch is,

Whene'er he hears upon a band

The too prolific Sousa's marches;

And from his eyes a tear he wipes,

Each time he sees the Stars and Stripes.

Tho' others roam across the foam

To European health resorts,

The fact that "there's no place like home"

Is foremost in our hero's thoughts;

And all in vain have people tried

To lure him from his "ain fireside."[36]

To European health resorts,

The fact that "there's no place like home"

Is foremost in our hero's thoughts;

And all in vain have people tried

To lure him from his "ain fireside."[36]

Let tourists travel near or far,

By wayward breezes widely blown,

He stops at the Astoria,

"A poor thing" (Shakespeare), "but his own;"

And nothing that his friends may do

Can drag him from Fifth Avenue.

By wayward breezes widely blown,

He stops at the Astoria,

"A poor thing" (Shakespeare), "but his own;"

And nothing that his friends may do

Can drag him from Fifth Avenue.

The Western heiress is content

To scale, as a prospective bride,

The bare six-story tenement

Where foreign pauper peers reside;

But men like Astor all disparage

The so-called Morgan-attic marriage.[37]

To scale, as a prospective bride,

The bare six-story tenement

Where foreign pauper peers reside;

But men like Astor all disparage

The so-called Morgan-attic marriage.[37]

The rich Chicago millionaire

May buy a mansion in Belgravia,

Have footmen there with powdered hair

And frigidly correct behaviour;

But marble stairs and plate of gold

Leave Astor absolutely cold.

May buy a mansion in Belgravia,

Have footmen there with powdered hair

And frigidly correct behaviour;

But marble stairs and plate of gold

Leave Astor absolutely cold.

The lofty ducal residence,

That fronts some Surrey riverside,

Would wound his socialistic sense,

And pain his patriotic pride;

He would not change for Castles Highland

His cabbage-patch on Coney Island.[38]

That fronts some Surrey riverside,

Would wound his socialistic sense,

And pain his patriotic pride;

He would not change for Castles Highland

His cabbage-patch on Coney Island.[38]

A statue in some Roman street,

A palace of Venetian gilding,

Appear to him not half so sweet

As any modern Vanderbuilding;

He views, without an envious throe,

The wolf that suckled Romeo!

A palace of Venetian gilding,

Appear to him not half so sweet

As any modern Vanderbuilding;

He views, without an envious throe,

The wolf that suckled Romeo!

Roast beef, or frogs, or sauerkraut,

Their mead of praise from some may win;

Our hero cannot do without

Peanuts and clams and terrapin;

Away from home, his soul would lack

The cocktail and the canvasback.[39]

Their mead of praise from some may win;

Our hero cannot do without

Peanuts and clams and terrapin;

Away from home, his soul would lack

The cocktail and the canvasback.[39]

Not his to walk the crowded Strand;

'Mid busy London's jar and hum.

On quiet Broadway he would stand,

Saying "Americanus sum!"

His smile so tranquil, so seraphic,—

Small wonder that it stops the traffic!

'Mid busy London's jar and hum.

On quiet Broadway he would stand,

Saying "Americanus sum!"

His smile so tranquil, so seraphic,—

Small wonder that it stops the traffic!

Who would not be a man like he,

(This lapse of grammar pray forgive,)

So simply satisfied to be,

Contented with his lot to live,—

Whether or not it be, I wot,

A little lot,—or quite a lot?[40]

(This lapse of grammar pray forgive,)

So simply satisfied to be,

Contented with his lot to live,—

Whether or not it be, I wot,

A little lot,—or quite a lot?[40]

Content with any kind of fare,

With any tiny piece of earth,

So long as he can find it there

Within the land that gave him birth;

Content with simple beans and pork,

If he may eat them in New York!

With any tiny piece of earth,

So long as he can find it there

Within the land that gave him birth;

Content with simple beans and pork,

If he may eat them in New York!

O persons who have made your pile,

And spend it far across the seas,

Like landlords of the Em'rald Isle,

Denounced notorious absentees,

I pray you imitate the Master,

And stay at home like Mr. Astor![41]

And spend it far across the seas,

Like landlords of the Em'rald Isle,

Denounced notorious absentees,

I pray you imitate the Master,

And stay at home like Mr. Astor![41]

But if you go abroad at all,

And leave your fatherland behind you,

Without an effort to recall

The sentimental ties that bind you,

I should be grateful if you could

Contrive to stay away for good!

[42]

And leave your fatherland behind you,

Without an effort to recall

The sentimental ties that bind you,

I should be grateful if you could

Contrive to stay away for good!

[42]

Henry VIII

ITH Stevenson we must agree,

Who found the world so full of things,

That all should be, or so said he,

As happy as a host of Kings;

Yet few so fortunate as not

To envy Bluff King Henry's lot.

[43]

A polished monarch, through and through,

Tho' somewhat lacking in religion,

Who joined a courtly manner to

The figure of a pouter pigeon;

And was, at time of feast or revel

A ... well ... a perfect little devil!

Tho' somewhat lacking in religion,

Who joined a courtly manner to

The figure of a pouter pigeon;

And was, at time of feast or revel

A ... well ... a perfect little devil!

But tho' his vices, I'm afraid,

Are hard for modern minds to swallow,

Two lofty virtues he displayed,

Which we should do our best to follow:—

A passion for domestic life,

A cult for what is called The Wife.[44]

Are hard for modern minds to swallow,

Two lofty virtues he displayed,

Which we should do our best to follow:—

A passion for domestic life,

A cult for what is called The Wife.[44]

He sought his spouses, North and South.

Six times (to make a misquotation)

He managed, at the Canon's mouth,

To win a bubble reputation;

And ev'ry time, from last to first,

His matrimonial bubble burst!

Six times (to make a misquotation)

He managed, at the Canon's mouth,

To win a bubble reputation;

And ev'ry time, from last to first,

His matrimonial bubble burst!

Six times, with wide, self-conscious smile

And well-blacked, button boots, he entered

The Abbey's bust-congested aisle,

With ev'ry eye upon him centred;

Six times he heard, and not alone,

The march of Mr. Mendelssohn.[45]

And well-blacked, button boots, he entered

The Abbey's bust-congested aisle,

With ev'ry eye upon him centred;

Six times he heard, and not alone,

The march of Mr. Mendelssohn.[45]

Six sep'rate times (or three times twice),

In order to complete the marriage,

'Mid painful show'rs of boots and rice,

He sought the shelter of his carriage;

Six times the bride, beneath her veil,

Looked "beautiful, but somewhat pale."

In order to complete the marriage,

'Mid painful show'rs of boots and rice,

He sought the shelter of his carriage;

Six times the bride, beneath her veil,

Looked "beautiful, but somewhat pale."

Within the limits of one reign,

Six females of undaunted bearing,

Two Annes, three Kath'rines, and a Jane,

Enjoyed the privilege of sharing

A conjugal career so chequer'd

It almost constitutes a record![46]

Six females of undaunted bearing,

Two Annes, three Kath'rines, and a Jane,

Enjoyed the privilege of sharing

A conjugal career so chequer'd

It almost constitutes a record![46]

Yet sometimes it occurs to me

That Henry missed his true vocation;

A husband by profession he,

A widower by occupation;

And, honestly, it seems a pity

He didn't live in Salt Lake City.

That Henry missed his true vocation;

A husband by profession he,

A widower by occupation;

And, honestly, it seems a pity

He didn't live in Salt Lake City.

For there he could have put in force

His plural marriage views, unbaffled;

Nor had recourse to dull divorce,

Nor sought the service of the scaffold;

Nor looked for peace, nor found release,

In any partner's predecease.[47]

His plural marriage views, unbaffled;

Nor had recourse to dull divorce,

Nor sought the service of the scaffold;

Nor looked for peace, nor found release,

In any partner's predecease.[47]

Had Henry been alive to-day,

He might have hired a timely motor,

And sent each wife in turn to stay

Within the confines of Dakota;

That State whose rigid marriage-law,

Is eulogised by Bernard Shaw.

He might have hired a timely motor,

And sent each wife in turn to stay

Within the confines of Dakota;

That State whose rigid marriage-law,

Is eulogised by Bernard Shaw.

But Henry's simple days are done,

And, in the present generation,

A wife is seldom woo'd and won

By prospects of decapitation.

For nowadays when Woman weds,

It is the Men who lose their heads!

[48]

And, in the present generation,

A wife is seldom woo'd and won

By prospects of decapitation.

For nowadays when Woman weds,

It is the Men who lose their heads!

[48]

Alton B. Parker

HOSE Roman Fathers, long ago,

Established a sublime tradition,

Who gave the Man Behind the Hoe

His proud proconsular position;

When Cincinnatus left his hens,

And beat his ploughshares into pens.

Established a sublime tradition,

Who gave the Man Behind the Hoe

His proud proconsular position;

When Cincinnatus left his hens,

And beat his ploughshares into pens.

[49]

His modern prototype we see,

Descended from some humble attic,

The Presidential nominee

Of those whose views are Democratic;

From Millionaire to Billiard Marker

They plumped their votes for Central Parker.

Descended from some humble attic,

The Presidential nominee

Of those whose views are Democratic;

From Millionaire to Billiard Marker

They plumped their votes for Central Parker.

A member of the sterner sex,

Possessing neither wealth nor beauty,

But gifted with a really ex—

—Traordinary sense of Duty;

In Honour's list I place him first,—

With Cæsar's Wife and Mr. Hearst.[50]

Possessing neither wealth nor beauty,

But gifted with a really ex—

—Traordinary sense of Duty;

In Honour's list I place him first,—

With Cæsar's Wife and Mr. Hearst.[50]

From childhood's day this son of toil,

Since first he laid aside his rattle,

Was wont to cultivate the soil,

Or milk his father's kindly cattle;

To groom the pigs, drive crows away,

Or teach the bantams how to lay.

Since first he laid aside his rattle,

Was wont to cultivate the soil,

Or milk his father's kindly cattle;

To groom the pigs, drive crows away,

Or teach the bantams how to lay.

This sprightly lad, his parents' pet,

With tastes essentially bucolic,

Eschewed the straightcut cigarette,

And shunned refreshments alcoholic;

His simple pleasure 'twas to plumb

The deep-laid joys of chewing gum.[51]

With tastes essentially bucolic,

Eschewed the straightcut cigarette,

And shunned refreshments alcoholic;

His simple pleasure 'twas to plumb

The deep-laid joys of chewing gum.[51]

As local pedagogue he next

Attained to years of indiscretion,

To preach the Solomonian text

So popular with that profession,

Which honours whom (and what) it teaches

More in th' observance than the breeches.

Attained to years of indiscretion,

To preach the Solomonian text

So popular with that profession,

Which honours whom (and what) it teaches

More in th' observance than the breeches.

The sprightly Parker soon one sees,

Head of a legal institution,

Enjoying huge retaining fees

As counsel for the prosecution.

(Advice to lawyers, meum non est,—

Get on, get honour, then get honest!)[52]

Head of a legal institution,

Enjoying huge retaining fees

As counsel for the prosecution.

(Advice to lawyers, meum non est,—

Get on, get honour, then get honest!)[52]

Behold him, then, like comet, shoot

Beyond the bounds of birth or station,

And gain, as jurist of repute,

A continental reputation.

(Don't mix him with that "Triple Star"

Which lights a more unworthy "bar.")

Beyond the bounds of birth or station,

And gain, as jurist of repute,

A continental reputation.

(Don't mix him with that "Triple Star"

Which lights a more unworthy "bar.")

A proud position now is his,

A judge, arrayed in moral ermine,

As from the Bench he sentences

His fellow-man, and other vermin,

And does his duty to his neighbour,

By giving him six months' hard labour.[53]

A judge, arrayed in moral ermine,

As from the Bench he sentences

His fellow-man, and other vermin,

And does his duty to his neighbour,

By giving him six months' hard labour.[53]

On knotty questions of finance

He bears aloft the golden standard,

For he whose motto is "Advance!"

To baser coin has never pandered.

No eulogist of War is he,

"Retrenchment!" is his dernier cri.

He bears aloft the golden standard,

For he whose motto is "Advance!"

To baser coin has never pandered.

No eulogist of War is he,

"Retrenchment!" is his dernier cri.

But tho', to his convictions true,

With strength like concentrated Eno,

He did his very utmost to

Emancipate the Filipino,

A fickle public chose Another,

Who called the Coloured Coon his Brother.

[54]

With strength like concentrated Eno,

He did his very utmost to

Emancipate the Filipino,

A fickle public chose Another,

Who called the Coloured Coon his Brother.

[54]

Euclid

HEN Egypt was a first-class Pow'r—

When Ptolemy was King, that is,

Whose benefices used to show'r

On all the local charities,

And by his liberal subscriptions

Was always spoiling the Egyptians—

When Ptolemy was King, that is,

Whose benefices used to show'r

On all the local charities,

And by his liberal subscriptions

Was always spoiling the Egyptians—

[55]

The Alexandrine School enjoyed

A proud and primary position

For training scholars not devoid

Of geometric erudition;

Where arithmetical fanatics

Could even live in (mathem)-attics.

A proud and primary position

For training scholars not devoid

Of geometric erudition;

Where arithmetical fanatics

Could even live in (mathem)-attics.

The best informed Historians name

This Institution the possessor

Of one who occupied with fame

The post of principal Professor,

Who had a more expansive brain

Than any man—before Hall Caine.[56]

This Institution the possessor

Of one who occupied with fame

The post of principal Professor,

Who had a more expansive brain

Than any man—before Hall Caine.[56]

No complex sums of huge amounts

Perplexed his algebraic knowledge;

With ease he balanced the accounts

Of his (at times insolvent) College;

He was, without the least romance,

A very Blondin of Finance.

Perplexed his algebraic knowledge;

With ease he balanced the accounts

Of his (at times insolvent) College;

He was, without the least romance,

A very Blondin of Finance.

In pencil, on his shirt-cuff, he,

Without a moment's hesitation,

Elucidated easily

The most elab'rate calculation

(His washing got, I needn't mention,

The local laundry's best attention).[57]

Without a moment's hesitation,

Elucidated easily

The most elab'rate calculation

(His washing got, I needn't mention,

The local laundry's best attention).[57]

Behind a manner mild as mouse,

Blue-spectacled and inoffensive,

He hid a judgment and a nous

As overwhelming as extensive,

And cloaked a soul immune from wrong

Beneath an ample ong-bong-pong.

Blue-spectacled and inoffensive,

He hid a judgment and a nous

As overwhelming as extensive,

And cloaked a soul immune from wrong

Beneath an ample ong-bong-pong.

To rows of conscientious youths,

Whom 'twas his duty to take care of,

He loved to prove the truth of truths

Which they already were aware of;

They learnt to look politely bored,

Where modern students would have snored.[58]

Whom 'twas his duty to take care of,

He loved to prove the truth of truths

Which they already were aware of;

They learnt to look politely bored,

Where modern students would have snored.[58]

To show that Two and Two make Four,

That All is greater than a Portion,

Requires no dialectic lore,

Nor any cerebral contortion;

The public's faith in facts was steady,

Before the days of Mrs. Eddy.

That All is greater than a Portion,

Requires no dialectic lore,

Nor any cerebral contortion;

The public's faith in facts was steady,

Before the days of Mrs. Eddy.

But what was hard to overlook

(From which Society still suffers)

Was all the trouble Euclid took

To teach the game of Bridge to duffers.

Insisting, when he got a quorum,

On "Pons" (he called it) "Asinorum."[59]

(From which Society still suffers)

Was all the trouble Euclid took

To teach the game of Bridge to duffers.

Insisting, when he got a quorum,

On "Pons" (he called it) "Asinorum."[59]

The guileless methods of his game

Provoked his partner's strongest strictures;

He hardly knew the cards by name,

But realised that some had pictures;

Exhausting ev'rybody's patience

By his perpetual revocations.

Provoked his partner's strongest strictures;

He hardly knew the cards by name,

But realised that some had pictures;

Exhausting ev'rybody's patience

By his perpetual revocations.

For weary hours, in deep concern,

O'er dummy's hand he loved to linger,

Denoting ev'ry card in turn,

With timid indecisive finger;

And stopped to say, at each delay,

"I really don't know what to play!"[60]

O'er dummy's hand he loved to linger,

Denoting ev'ry card in turn,

With timid indecisive finger;

And stopped to say, at each delay,

"I really don't know what to play!"[60]

He sought, at any cost, to win

His ev'ry suit in turn unguarding;

He trumped his partner's "best card in,"

His own egregiously discarding;

Remarking sadly, when in doubt,

"I quite forgot the King was out!"

His ev'ry suit in turn unguarding;

He trumped his partner's "best card in,"

His own egregiously discarding;

Remarking sadly, when in doubt,

"I quite forgot the King was out!"

Alert opponents always knew,

By what the look upon his face was,

When safety lay in leading through,

And where, of course, the fatal ace was;

Assuring the complete successes

Of bold but hazardous "finesses."[61]

By what the look upon his face was,

When safety lay in leading through,

And where, of course, the fatal ace was;

Assuring the complete successes

Of bold but hazardous "finesses."[61]

But nowadays we find no trace,

From distant Assouan to Cairo,

To mark the place where dwelt a race

Mistaught by so absurd a tyro;

And nothing but occult inscriptions

Recall the sports of past Egyptians.

From distant Assouan to Cairo,

To mark the place where dwelt a race

Mistaught by so absurd a tyro;

And nothing but occult inscriptions

Recall the sports of past Egyptians.

Yes, "autre temps" and "autre moeurs,"

"Où sont indeed les neiges d'antan?"

The modern native much prefers

Debauching in some café chantant,

Nor ever shows the least ambition

To solve a single Proposition.[62]

"Où sont indeed les neiges d'antan?"

The modern native much prefers

Debauching in some café chantant,

Nor ever shows the least ambition

To solve a single Proposition.[62]

O Euclid, luckiest of men!

You knew no English interloper;

For Allah's Garden was not then

The pleasure-ground of Alleh Sloper,

Nor (broth-like) had your country's looks

Been spoilt by an excess of "Cooks."

You knew no English interloper;

For Allah's Garden was not then

The pleasure-ground of Alleh Sloper,

Nor (broth-like) had your country's looks

Been spoilt by an excess of "Cooks."

The Nile to your untutored ears

Discoursed in dull but tender tones;

Not yours the modern Dahabeahs,

Supplied with strident gramophones,

Imploring, in a loud refrain,

Bill Bailey to come home again.[63]

Discoursed in dull but tender tones;

Not yours the modern Dahabeahs,

Supplied with strident gramophones,

Imploring, in a loud refrain,

Bill Bailey to come home again.[63]

Your cars, the older-fashioned sort,

And drawn, perhaps, by alligators,

Were not the modern Juggernaut-

Child-dog-and-space-obliterators,

Those "stormy petrols" of the land

Which deal decease on either hand.

And drawn, perhaps, by alligators,

Were not the modern Juggernaut-

Child-dog-and-space-obliterators,

Those "stormy petrols" of the land

Which deal decease on either hand.

No European tourist wags

Defiled the desert's dusky face

With orange peel and paper bags,

Those emblems of a cultured race;

Or cut the noble name of Jones,

On tombs which held a monarch's bones.[64]

Defiled the desert's dusky face

With orange peel and paper bags,

Those emblems of a cultured race;

Or cut the noble name of Jones,

On tombs which held a monarch's bones.[64]

O Euclid! Could you see to-day

The sunny clime you once frequented,

And note the way we moderns play

The game you thoughtfully invented,

The knowledge of your guilt would force yer

To feelings of internal nausea!

[65]

The sunny clime you once frequented,

And note the way we moderns play

The game you thoughtfully invented,

The knowledge of your guilt would force yer

To feelings of internal nausea!

[65]

J. M. Barrie

HE briny tears unbidden start,

At mention of my hero's name!

Was ever set so huge a heart

Within so small a frame?

So much of tenderness and grace

Confined in such a slender space?[66]

At mention of my hero's name!

Was ever set so huge a heart

Within so small a frame?

So much of tenderness and grace

Confined in such a slender space?[66]

(O tiniest of tiny men!

So wise, so whimsical, so witty!

Whose magic little fairy-pen

Is steeped in human pity;

Whose humour plays so quaint a tune,

From Peter Pan to Pantaloon!)

So wise, so whimsical, so witty!

Whose magic little fairy-pen

Is steeped in human pity;

Whose humour plays so quaint a tune,

From Peter Pan to Pantaloon!)

So wide a sympathy has he,

Such kindliness without an end,

That children clamber on his knee,

And claim him as a friend;

They somehow know he understands,

And doesn't mind their sticky hands.

Such kindliness without an end,

That children clamber on his knee,

And claim him as a friend;

They somehow know he understands,

And doesn't mind their sticky hands.

[67]And so they swarm about his neck,

With energy that nothing wearies,

Assured that he will never check

Their ceaseless flow of queries,

And grateful, with a warm affection,

For his avuncular protection.

With energy that nothing wearies,

Assured that he will never check

Their ceaseless flow of queries,

And grateful, with a warm affection,

For his avuncular protection.

And when his watch he opens wide,

Or beats them all at blowing bubbles,

They tell him how the dormouse died,

And all their tiny troubles;

And drag him, if he seems deprest,

To see the baby squirrel's nest.[68]

Or beats them all at blowing bubbles,

They tell him how the dormouse died,

And all their tiny troubles;

And drag him, if he seems deprest,

To see the baby squirrel's nest.[68]

For hidden treasure he can dig,

Pursue the Indians in the wood,

Feed the prolific guinea-pig

With inappropriate food;

Do all the things that mattered so

In happy days of long ago.

Pursue the Indians in the wood,

Feed the prolific guinea-pig

With inappropriate food;

Do all the things that mattered so

In happy days of long ago.

All this he can achieve, and more!

For, 'neath the magic of his brain,

The young are younger than before,

The old grow young again,

To dream of Beauty and of Truth

For hearts that win eternal youth.[69]

For, 'neath the magic of his brain,

The young are younger than before,

The old grow young again,

To dream of Beauty and of Truth

For hearts that win eternal youth.[69]

Fat apoplectic men I know,

With well-developed Little Marys,

Look almost human when they show

Their faith in Barrie's fairies;

Their blank lethargic faces lighten

In admiration of his Crichton.

With well-developed Little Marys,

Look almost human when they show

Their faith in Barrie's fairies;

Their blank lethargic faces lighten

In admiration of his Crichton.

To lovers who, with fingers cold,

Attempt to fan some dying ember,

He brings the happy days of old,

And bids their hearts remember;

Recalling in romantic fashion

The tenderness of earlier passion.[70]

Attempt to fan some dying ember,

He brings the happy days of old,

And bids their hearts remember;

Recalling in romantic fashion

The tenderness of earlier passion.[70]

And modern matrons who can find

So little leisure for the Nurs'ry,

Whose interest in babykind

Is eminently curs'ry,

New views on Motherhood acquire

From Alice-sitting-by-the-Fire!

So little leisure for the Nurs'ry,

Whose interest in babykind

Is eminently curs'ry,

New views on Motherhood acquire

From Alice-sitting-by-the-Fire!

While men of every sort and kind,

At times of sunshine or of trouble,

In Sentimental Tommy find

Their own amazing double;

To each in turn the mem'ry comes

Of some belov'd forgotten Thrums.[71]

At times of sunshine or of trouble,

In Sentimental Tommy find

Their own amazing double;

To each in turn the mem'ry comes

Of some belov'd forgotten Thrums.[71]

To Barrie's literary art

That strong poetic sense is clinging

Which hears, in ev'ry human heart,

A "late lark" faintly singing,

A bird that bears upon its wing

The promise of perpetual Spring.

That strong poetic sense is clinging

Which hears, in ev'ry human heart,

A "late lark" faintly singing,

A bird that bears upon its wing

The promise of perpetual Spring.

Materialists may labour much

At problems for the modern stage;

His simpler methods reach and touch

The Young of ev'ry age;

And first and second childhood meet

On common ground at Barrie's feet!

[72]

At problems for the modern stage;

His simpler methods reach and touch

The Young of ev'ry age;

And first and second childhood meet

On common ground at Barrie's feet!

[72]

Omar Khayyam

HOUGH many a great Philosopher

Has earned the Epicure's diploma,

Not one of them, as I aver,

So much deserved the prize as Omar;

For he, without the least misgiving,

Combined High Thinking and High Living.

Has earned the Epicure's diploma,

Not one of them, as I aver,

So much deserved the prize as Omar;

For he, without the least misgiving,

Combined High Thinking and High Living.

[73]

He lived in Persia, long ago,

Upon a somewhat slender pittance;

And Persia is, as you may know,

The home of Shahs and fubsy kittens,

(A quite consistent habitat,

Since "Shah," of course, is French for "cat.")

Upon a somewhat slender pittance;

And Persia is, as you may know,

The home of Shahs and fubsy kittens,

(A quite consistent habitat,

Since "Shah," of course, is French for "cat.")

He lived—as I was saying, when

You interrupted, impolitely—

Not loosely, like his fellow-men,

But, vicê versâ, rather tightly;

And drank his share, so runs the story,

And other people's, con amore.[74]

You interrupted, impolitely—

Not loosely, like his fellow-men,

But, vicê versâ, rather tightly;

And drank his share, so runs the story,

And other people's, con amore.[74]

A great Astronomer, no doubt,

He often found some Constellation

Which others could not see without

Profuse internal irrigation;

And snakes he saw, and crimson mice,

Until his colleagues rang for ice.

He often found some Constellation

Which others could not see without

Profuse internal irrigation;

And snakes he saw, and crimson mice,

Until his colleagues rang for ice.

Omar, who owned a length of throat

As dry as the proverbial "drummer,"

And quite believed that (let me quote)

"One swallow does not make a summer,"

Supplied a model to society

Of frank, persistent insobriety.

[75] * * * * *

Ah, fill the cup with nectar sweet,

Until, when indisposed for more,

Your puzzled, inadhesive feet

Elude the smooth revolving floor.

What matter doubts, despair or sorrow?

To-day is Yesterday To-morrow!

As dry as the proverbial "drummer,"

And quite believed that (let me quote)

"One swallow does not make a summer,"

Supplied a model to society

Of frank, persistent insobriety.

[75] * * * * *

Ah, fill the cup with nectar sweet,

Until, when indisposed for more,

Your puzzled, inadhesive feet

Elude the smooth revolving floor.

What matter doubts, despair or sorrow?

To-day is Yesterday To-morrow!

Oblivion in the bottle win,

Let finger-bowls with vodka foam,

And seek the Open Port within

Some dignified Inebriates' Home;

Assuming there, with kingly air,

A crown of vine-leaves in your hair![76]

Let finger-bowls with vodka foam,

And seek the Open Port within

Some dignified Inebriates' Home;

Assuming there, with kingly air,

A crown of vine-leaves in your hair![76]

A book of verse (my own, for choice),

A slice of cake, some ice-cream soda,

A lady with a tuneful voice,

Beside me in some dim pagoda!

A cellar—if I had the key,—

Would be a Paradise to me!

A slice of cake, some ice-cream soda,

A lady with a tuneful voice,

Beside me in some dim pagoda!

A cellar—if I had the key,—

Would be a Paradise to me!

In cosy seat, with lots to eat,

And bottles of Lafitte to fracture

(And, by-the-bye, the word La-feet

Recalls the mode of manufacture)—

I contemplate, at easy distance,

The troublous problems of existence.[77]

And bottles of Lafitte to fracture

(And, by-the-bye, the word La-feet

Recalls the mode of manufacture)—

I contemplate, at easy distance,

The troublous problems of existence.[77]

For even if it could be mine

To change Creation's partial scheme,

To mould it to a fresh design,

More nearly that of which I dream,

Most probably, my weak endeavour

Would make more mess of it than ever!

To change Creation's partial scheme,

To mould it to a fresh design,

More nearly that of which I dream,

Most probably, my weak endeavour

Would make more mess of it than ever!

So let us stock our cellar shelves

With balm to lubricate the throttle;

For "Heav'n helps those who help themselves,"

So help yourself, and pass the bottle!

. . . . . .

What! Would you quarrel with my moral?

(Waiter! Leshavanotherborrel!)

[78]

With balm to lubricate the throttle;

For "Heav'n helps those who help themselves,"

So help yourself, and pass the bottle!

. . . . . .

What! Would you quarrel with my moral?

(Waiter! Leshavanotherborrel!)

[78]

Andrew Carnegie

N Caledonia, stern and wild,

N Caledonia, stern and wild,

Whence scholars, statesmen, bards have sprung,

Where ev'ry little barefoot child

Correctly lisps his mother-tongue,

And lingual solecisms betokenWhere ev'ry little barefoot child

Correctly lisps his mother-tongue,

That Scotch is drunk, as well as spoken,[79]

There dwells a man of iron nerve,

A millionaire without a peer,

Possessing that supreme reserve

Which stamps the caste of Vere de Vere,

And marks him out to human ken

As one of Nature's noblemen.

Like other self-made persons, he

Is surely much to be excused,

Since they have had no choice, you see,

Of the material to be used;

But when his noiseless fabric grew,

He builded better than he knew.[80]

Is surely much to be excused,

Since they have had no choice, you see,

Of the material to be used;

But when his noiseless fabric grew,

He builded better than he knew.[80]

A democrat, whose views are frank,

To him Success alone is vital;

He deems the wealthy cabman's "rank"

As good as any other title;

To him the post of postman betters

The trade of other Men of Letters.

To him Success alone is vital;

He deems the wealthy cabman's "rank"

As good as any other title;

To him the post of postman betters

The trade of other Men of Letters.

The relative who seeks to wed

Some nice but indigent patrician,

He urges to select instead

A coachman of assured position,

Since safety-matches, you'll agree,

Strike only on the box, says he.[81]

Some nice but indigent patrician,

He urges to select instead

A coachman of assured position,

Since safety-matches, you'll agree,

Strike only on the box, says he.[81]

At Skibo Castle, by the sea,

A splendid palace he has built,

Equipped with all the luxury

Of plush, of looking-glass, and gilt;

A style which Ruskin much enjoyed,

And christened "Early German Lloyd."

A splendid palace he has built,

Equipped with all the luxury

Of plush, of looking-glass, and gilt;

A style which Ruskin much enjoyed,

And christened "Early German Lloyd."

With milking-stools and ribbon'd screens

The floor is covered, well I know;

The walls are thick with tambourines,

Hand-painted many years ago;

Ah, how much taste our forbears had!

And nearly all of it was bad.[82]

The floor is covered, well I know;

The walls are thick with tambourines,

Hand-painted many years ago;

Ah, how much taste our forbears had!

And nearly all of it was bad.[82]

Each flow'r-embroidered boudoir suite,

Each "cosy corner" set apart,

Was modelled in the Regent Street

Emporium of suburban art.

"O Liberty!" (I quote with shame)

"The crimes committed in thy name!"

Each "cosy corner" set apart,

Was modelled in the Regent Street

Emporium of suburban art.

"O Liberty!" (I quote with shame)

"The crimes committed in thy name!"

But tho' his mansion now contains

A swimming-bath, a barrel-organ,

Electric light, and even drains,

As good as those of Mr. Morgan,

There was a time when Andrew C.

Was not obsessed by l. s. d.[83]

A swimming-bath, a barrel-organ,

Electric light, and even drains,

As good as those of Mr. Morgan,

There was a time when Andrew C.

Was not obsessed by l. s. d.[83]

Across the seas he made his pile,

In Pittsburg, where, I've understood,

You have to exercise some guile

To do the very slightest good;

But he kept doing good by stealth,

And doubtless blushed to find it wealth.

In Pittsburg, where, I've understood,

You have to exercise some guile

To do the very slightest good;

But he kept doing good by stealth,

And doubtless blushed to find it wealth.

And now his private hobby 'tis

To meet a starving people's need

By making gifts of libraries

To those who never learnt to read;

Rich mental banquets he provides

For folks with famishing insides.[84]

To meet a starving people's need

By making gifts of libraries

To those who never learnt to read;

Rich mental banquets he provides

For folks with famishing insides.[84]

In Education's hallowed name

He pours his opulent libations;

His vast deserted Halls of Fame

Increase the gaiety of nations.

But still the slums are plague-infested,

The hospitals remain congested.

. . . . . .

Carnegie, should your kindly eye

This foolish book of verses meet,

Please order an immense supply,

To make your libraries complete,

And register its author's name

Within your princely Halls of Fame!

[85]

He pours his opulent libations;

His vast deserted Halls of Fame

Increase the gaiety of nations.

But still the slums are plague-infested,

The hospitals remain congested.

. . . . . .

Carnegie, should your kindly eye

This foolish book of verses meet,

Please order an immense supply,

To make your libraries complete,

And register its author's name

Within your princely Halls of Fame!

[85]

King Cophetua

O sing of King Cophetua

I am indeed unwilling,

For none of his adventures are

Particularly thrilling;

Nor, as I hardly need to mention,

Am I addicted to invention.[86]

I am indeed unwilling,

For none of his adventures are

Particularly thrilling;

Nor, as I hardly need to mention,

Am I addicted to invention.[86]

The story of his roving eye,

You must already know it,

Since it has been narrated by

Lord Tennyson, the poet;

I could a moving tale unfold,

But it has been so often told.

You must already know it,

Since it has been narrated by

Lord Tennyson, the poet;

I could a moving tale unfold,

But it has been so often told.

But since I wish my friends to see

My early education,

If Tennyson will pardon me

A somewhat free translation,

I'll try if something can't be sung

In someone else's mother-tongue.

My early education,

If Tennyson will pardon me

A somewhat free translation,

I'll try if something can't be sung

In someone else's mother-tongue.

[87]"Cophetua and the Beggar Maid!"

So runs the story's title

(An explanation, I'm afraid,

Is absolutely vital),

Express'd, as I need hardly mench:

In 4 a.m. (or early) French:—

So runs the story's title

(An explanation, I'm afraid,

Is absolutely vital),

Express'd, as I need hardly mench:

In 4 a.m. (or early) French:—

Les bras posés sur la poitrine

Lui fait l'apparence divine,—

Enfin elle a très bonne mine,—

Elle arrive, ne portant pas

De sabots, ni même de bas,

Pieds-nus, au roi Cophetua.[88]

Lui fait l'apparence divine,—

Enfin elle a très bonne mine,—

Elle arrive, ne portant pas

De sabots, ni même de bas,

Pieds-nus, au roi Cophetua.[88]

Le roi lors, couronne sur tête,

Vêtu de ses robes de fête,

Va la rencontrer, et l'arrête.

On dit, "Tiens, il y en a de quoi!"

"Je ferais ça si c'était moi!"

Il saits s'amuser donc, ce roi!

Vêtu de ses robes de fête,

Va la rencontrer, et l'arrête.

On dit, "Tiens, il y en a de quoi!"

"Je ferais ça si c'était moi!"

Il saits s'amuser donc, ce roi!

Ainsi qu'la lune brille aux cieux,

Cette enfant luit de mieux en mieux,

Quand même ses habits soient vieux.

En voilà un qui loue ses yeux,

Un autre admire ses cheveux,

Et tout le monde est amoureux.[89]

Cette enfant luit de mieux en mieux,

Quand même ses habits soient vieux.

En voilà un qui loue ses yeux,

Un autre admire ses cheveux,

Et tout le monde est amoureux.[89]

Car on n'a jamais vu là-bas

Un charme tel que celui-là

Alors le bon Cophetua

Jure, "La pauvre mendiante,

Si séduisante, si charmante,

Sera ma femme,—ou bien ma tante!"

[90]

Un charme tel que celui-là

Alors le bon Cophetua

Jure, "La pauvre mendiante,

Si séduisante, si charmante,

Sera ma femme,—ou bien ma tante!"

[90]

Joseph F. Smith

HOUGH, to the ordinary mind,

The weight of marriage ties is such

That many mere, male, mortals find

One wife enough,—if not too much;

I see no no reason to abuse

A person holding other views.

The weight of marriage ties is such

That many mere, male, mortals find

One wife enough,—if not too much;

I see no no reason to abuse

A person holding other views.

[91]

Though most of us, at any rate,

Have not acquired the plural habits,

Which we are apt to delegate

To Eastern potentates,—or rabbits;

We should regard with open mind

The more uxoriously inclined.

Have not acquired the plural habits,

Which we are apt to delegate

To Eastern potentates,—or rabbits;

We should regard with open mind

The more uxoriously inclined.

In Salt Lake City dwells a man

Who deems monogamy a myth;

(One of that too prolific clan

Which glories in the name of Smith);

A "Prophet, Seer, and Revelator,"

With the appearance of a waiter.[92]

Who deems monogamy a myth;

(One of that too prolific clan

Which glories in the name of Smith);

A "Prophet, Seer, and Revelator,"

With the appearance of a waiter.[92]

This hoary patriarch contrives

To thrive in manner most bewild'rin',

With close on half a dozen wives,

And nearly half a hundred children;

And views with unaffrighted eyes

The burden of domestic ties.

To thrive in manner most bewild'rin',

With close on half a dozen wives,

And nearly half a hundred children;

And views with unaffrighted eyes

The burden of domestic ties.

To him all spouses seem the same—

Each one a model of the Graces;

He knows his children all by name,

But cannot recollect their faces;

A minor point, since, I suppose,

Each one has got its popper's nose![93]

Each one a model of the Graces;

He knows his children all by name,

But cannot recollect their faces;

A minor point, since, I suppose,

Each one has got its popper's nose![93]

They are denied to me and you:

Such old-world luxuries as his,

When, after work, he hastens to

The bosoms of his families

(Each offspring joining with the others

In, "What is Home without five Mothers?").

Such old-world luxuries as his,

When, after work, he hastens to

The bosoms of his families

(Each offspring joining with the others

In, "What is Home without five Mothers?").

Such strange surroundings would retard

Most ordinary men's digestions;

Five ladies all conversing hard,

And fifty children asking questions!

Besides (the tragic final straw),

Five se-pa-rate mamas-in-law![94]

Most ordinary men's digestions;

Five ladies all conversing hard,

And fifty children asking questions!

Besides (the tragic final straw),

Five se-pa-rate mamas-in-law![94]

What difficulties there must be

To find a telescopic mansion;

For each successive family

The space sufficient for expansion.

("But that," said Kipling, in his glory—

"But that is quite another storey!")

To find a telescopic mansion;

For each successive family

The space sufficient for expansion.

("But that," said Kipling, in his glory—

"But that is quite another storey!")

The sailor who, from lack of thought,

Or else a too diffuse affection,

Has, for a wife in ev'ry port,

An unappeasing predilection,

Would designate as "simply great!"

The mode of life in Utah State.[95]

Or else a too diffuse affection,

Has, for a wife in ev'ry port,

An unappeasing predilection,

Would designate as "simply great!"

The mode of life in Utah State.[95]

The gay Lothario, too, who makes

His mad but meaningless advances

To more than one fair maid, and takes

A large variety of chances,

Need have no fear, in such a place,

Of any breach-of-promise case.

His mad but meaningless advances

To more than one fair maid, and takes

A large variety of chances,

Need have no fear, in such a place,

Of any breach-of-promise case.

With Mormons of the latter-day

I have no slightest cause for quarrel;

Nor do I doubt at all that they

Are quite exceptionally moral;

Their President has told us so,

And he, if anyone, should know.[96]

I have no slightest cause for quarrel;

Nor do I doubt at all that they

Are quite exceptionally moral;

Their President has told us so,

And he, if anyone, should know.[96]

But tho' of folks in Utah State,

But 2 percent lead plural lives,

Perhaps the other 98

Are just—their children and their wives!

O stern, ascetic congregation,

Resisting all—except temptation!

But 2 percent lead plural lives,

Perhaps the other 98

Are just—their children and their wives!

O stern, ascetic congregation,

Resisting all—except temptation!

Well, I, for one, can see no harm,

Unless for trouble one were looking,

In having wives on either arm,

And one downstairs—to do the cooking.

A touching scene; with nought to dim it.

But fifty children!—That's the limit![97]

Unless for trouble one were looking,

In having wives on either arm,

And one downstairs—to do the cooking.

A touching scene; with nought to dim it.

But fifty children!—That's the limit![97]

Some middle course would I explore;

Incur a merely dual bond;

One wife, brunette, to scrub the floor,

And one for outdoor use, a blonde;

Thus happily could I exist,

A moral Mormonogamist!

[98]

Incur a merely dual bond;

One wife, brunette, to scrub the floor,

And one for outdoor use, a blonde;

Thus happily could I exist,

A moral Mormonogamist!

[98]

Sherlock Holmes

HE French "filou" may raise his "bock,"

The "Green-goods man" his cocktail, when

He toast Gaboriau's Le Coq,

Or Pinkerton's discreet young men;

But beer in British bumpers foams

Around the name of Sherlock Holmes!

The "Green-goods man" his cocktail, when

He toast Gaboriau's Le Coq,

Or Pinkerton's discreet young men;

But beer in British bumpers foams

Around the name of Sherlock Holmes!

[99]

Come, boon companions, all of you

Who (woodcock-like) exist by suction,

Uplift your teeming tankards to

The great Professor of Deduction!

Who is he? You shall shortly see

If (Watson-like) you "follow me."

Who (woodcock-like) exist by suction,

Uplift your teeming tankards to

The great Professor of Deduction!

Who is he? You shall shortly see

If (Watson-like) you "follow me."

In London (on the left-hand side

As you go in), stands Baker Street,

Exhibited with proper pride

By all policemen on the beat,

As housing one whose predilection

Is private criminal detection.[100]

As you go in), stands Baker Street,

Exhibited with proper pride

By all policemen on the beat,

As housing one whose predilection

Is private criminal detection.[100]

The malefactor's apt disguise

Presents to him an easy task;

His placid, penetrating eyes

Can pierce the most secretive mask;

And felons ask a deal too much

Who fancy to elude his clutch.

Presents to him an easy task;

His placid, penetrating eyes

Can pierce the most secretive mask;

And felons ask a deal too much

Who fancy to elude his clutch.

No slender or exiguous clew

Too paltry for his needs is found;

No knot too stubborn to undo,

No prey too swift to run to ground;

No road too difficult to travel,

No skein too tangled to unravel.[101]

Too paltry for his needs is found;

No knot too stubborn to undo,

No prey too swift to run to ground;

No road too difficult to travel,

No skein too tangled to unravel.[101]

For Holmes the ash of a cigar,

A gnat impinging on his eye,

Possess a meaning subtler far

Than humbler mortals can descry.

A primrose at the river's brim

No simple primrose is to him!

A gnat impinging on his eye,

Possess a meaning subtler far

Than humbler mortals can descry.

A primrose at the river's brim

No simple primrose is to him!

To Holmes a battered Brahma key,

Combined with blurred articulation,

Displays a man's capacity

For infinite ingurgitation;

Obliquity of moral vision

Betrays the civic politician.[102]

Combined with blurred articulation,

Displays a man's capacity

For infinite ingurgitation;

Obliquity of moral vision

Betrays the civic politician.[102]

I had an uncle, who possessed

A marked resemblance to a bloater,

Whom Sherlock, by deduction, guessed

To be the victim of a motor;

Whereas, his wife (or so he swore)

Had merely shut him in the door!

A marked resemblance to a bloater,

Whom Sherlock, by deduction, guessed

To be the victim of a motor;

Whereas, his wife (or so he swore)

Had merely shut him in the door!

My brother's nose, whose hectic hue

Recalled the sun-kissed autumn leaf,

Though friends attributed it to

Some secret or domestic grief,

Revealed to Holmes his deep potations,

And not the loss of loved relations![103]

Recalled the sun-kissed autumn leaf,

Though friends attributed it to

Some secret or domestic grief,

Revealed to Holmes his deep potations,

And not the loss of loved relations![103]

I had a poodle, short and fat,

Who proved a conjugal deceiver;

Her offspring were a Maltese Cat,

Two Dachshunds and a pink retriever!

Her husband was a pure-bred Skye;

And Sherlock Holmes alone knew why!

Who proved a conjugal deceiver;

Her offspring were a Maltese Cat,

Two Dachshunds and a pink retriever!

Her husband was a pure-bred Skye;

And Sherlock Holmes alone knew why!

When after-dinner speakers rise,

To plunge in anecdotage deep,

At once will Sherlock recognise

Each welcome harbinger of sleep:

That voice which torpid guests entrances,

That immemorial voice of Chauncey's![104]

To plunge in anecdotage deep,

At once will Sherlock recognise

Each welcome harbinger of sleep:

That voice which torpid guests entrances,

That immemorial voice of Chauncey's![104]

Not his, suppose Hall Caine should walk

All unannounced into the room,

To say, like pressmen of New York,

"Er—Mr. Shakespeare, I presoom?"

By name "The Manxman" Holmes would hail,

Observing that he had no tale.

All unannounced into the room,

To say, like pressmen of New York,

"Er—Mr. Shakespeare, I presoom?"

By name "The Manxman" Holmes would hail,

Observing that he had no tale.

In vain, amid the lonely state

Of Zion, dreariest of havens,

Does bashful Dowie emulate

The prophet who was fed by ravens;

To Holmes such affluence betrays

A prophet who is fed by jays!

[105] . . . . . .

With Holmes there lived a foolish man,

To whom I briefly must allude,

Who gloried in possessing an

Abnormal mental hebetude;

One could describe the grossest bétise

To this (forgive the rhyme) Achates.

Of Zion, dreariest of havens,

Does bashful Dowie emulate

The prophet who was fed by ravens;

To Holmes such affluence betrays

A prophet who is fed by jays!

[105] . . . . . .

With Holmes there lived a foolish man,

To whom I briefly must allude,

Who gloried in possessing an

Abnormal mental hebetude;

One could describe the grossest bétise

To this (forgive the rhyme) Achates.

'Twas Doctor Watson, human mole,

Obtusely, painfully polite;

Who played the unambitious rôle

Of parasitic satellite;

Inevitably bound to bore us,

Like Aristophanes's Chorus.

[106] . . . . . .

But London town is sad to-day,

And preternaturally solemn;

The fountains murmur "Let us spray"

To Nelson on his lonely column;

Big Ben is mute, her clapper crack'd is,

For Holmes has given up his practice.

Obtusely, painfully polite;

Who played the unambitious rôle

Of parasitic satellite;

Inevitably bound to bore us,

Like Aristophanes's Chorus.

[106] . . . . . .

But London town is sad to-day,

And preternaturally solemn;

The fountains murmur "Let us spray"

To Nelson on his lonely column;

Big Ben is mute, her clapper crack'd is,

For Holmes has given up his practice.

No more in silence, as the snake,

Will he his sinuous path pursue,

Till, like the weasel (when awake),

Or deft, resilient kangaroo,

He leaps upon his quivering quarry,

Before there's time to say you're sorry.[107]

Will he his sinuous path pursue,

Till, like the weasel (when awake),

Or deft, resilient kangaroo,

He leaps upon his quivering quarry,

Before there's time to say you're sorry.[107]

No more will criminals, at dawn,

Effecting some burglarious entry,

(While Sherlock, on the garden lawn,

Enacts the thankless rôle of sentry),

Discover, to their bitter cost,

That felons who are found—are lost!

Effecting some burglarious entry,

(While Sherlock, on the garden lawn,

Enacts the thankless rôle of sentry),

Discover, to their bitter cost,

That felons who are found—are lost!

No more on Holmes shall Watson base

The Chronicles he proudly fabled;

The violin and morphia-case

Are in the passage, packed and labelled;

And Holmes himself is at the door,

Departing—to return no more.[108]

The Chronicles he proudly fabled;

The violin and morphia-case

Are in the passage, packed and labelled;

And Holmes himself is at the door,

Departing—to return no more.[108]

He bids farewell to Baker Street,

Though Watson clings about his knees;

He hastens to his country seat,