The Project Gutenberg EBook of Lachesis Lapponica, by Carl von Linné

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Lachesis Lapponica

A Tour in Lapland

Author: Carl von Linné

Editor: James Edward Smith

Translator: Charles Troilius

Release Date: May 8, 2011 [EBook #36059]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK LACHESIS LAPPONICA ***

Produced by Simon Gardner, Robert Connal, Chris Curnow and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

Unusual or inconsistent spellings, hyphenation and punctuation are retained as printed except where typographical errors have been corrected: any corrections are listed at the end of the book.

Hyperlink cross-references are provided to pages in this volume only.

If the following Greek symbols do not appear (β, γ, λ, κ) in your browser then a Unicode font should be selected.

OR A

NOW FIRST PUBLISHED

from the

ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPT JOURNAL

OF THE CELEBRATED

LINNÆUS;

by

JAMES EDWARD SMITH, M.D. F.R.S. ETC.

PRESIDENT OF THE LINNÆAN SOCIETY.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

"Ulterius nihil est, nisi non habitabile frigus."

Ovid.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR WHITE AND COCHRANE, HORACE'S HEAD,

FLEET-STREET,

BY RICHARD TAYLOR AND CO., SHOE-LANE.

1811.

In the latter part of this day, July 15th, I set out on my return from the low grounds of Norway. The heat was very powerful as we began to ascend the mountains. When we reached what had seemed to us from below the summit of a hill, we saw just as lofty an eminence before us, and this was the case nine or ten successive times. I had no idea of such mountains before. The elevation of this hill cannot be taken by any geometrical instrument, as the summit is not visible, even at some miles distance. I believe its height must exceed a Swedish mile, but to climb it was [Pg 2]worse than going two miles any other way. Had we not frequently met with such abundance of water, we should have been overcome with fatigue. In this ascent I found the little Astragalus (alpinus) with a white flower, and the Little Gentian (Gentiana nivalis).

Our clothes, which were wet quite through with perspiration, in consequence of the heat we had encountered in the beginning of our journey, were now frozen stiff upon our backs by the cold. We determined to seek for a Laplander's hut. In order to get at one, we were obliged to descend so steep a hill, that, being unable to walk down it, I lay down on my back and slid along, with the rapidity of an arrow from a bow. I avoided with difficulty the large snow torrents that every now and then came in my way, and which were sometimes within an ell of me.

On reaching this hut, I noticed some of the reindeer whose horns were not above half an inch long, the Brom-fly (Oestrus Tarandi)[Pg 3] having bitten them while quite tender; for these insects are, in the Norwegian alps, worse than the gnats of Swedish Lapland.

I here obtained a curious piece of information respecting the mode of castrating the reindeer. When the animal is two years and a half old, its owner, about a fortnight before Michaelmas, getting a person to assist him by holding it fast by the horns, places himself betwixt its hind legs. He then applies his teeth to the scrotum, so as to bruise its contents, but not so as to break the skin, for in that case the reindeer would die. He afterwards bruises the part still more effectually between his fingers. The same operation is performed on both sides, if the reindeer remains quiet long enough for the purpose at one time. The animal is in consequence rather indisposed for a while, so that he can hardly keep up with the rest of the herd, but he usually recovers perfectly in a week's time. This is certainly an art, no less curious than remarkable, and merits further consideration.[Pg 4]

The girls here, especially when they wish to appear to advantage, divide their hair into two braids, one above each ear, which braids are tied together, at the hind part of the head, so as to hang down the back. A tuft of ribands is appended to the extremity of each braid.

We undertook to cross the ice-mountain. Having proceeded some way on our journey, we observed a dense cloud to the north-east. It was visible both above and below us, and at length approached us in the form of a thick mist, which moistened our clothes, and rendered even our hair thoroughly wet. It so completely obliterated our horizon, that we could neither see sun nor moon, nor the summits of the neighbouring hills. We knew not whither to turn our steps, fearing on the one hand to fall down a precipice and lose our lives, as actually happened, a few years ago, to a Laplander under the same circumstances; or on the[Pg 5] other to be plunged into the alpine torrent, which had worn so deep a channel through the snow, as to make any one giddy, looking upon it from above. We could now not distinguish any thing a couple of ells before us. Our situation was like that of an unskilful mariner at sea without a compass, out of sight of land, and surrounded by hidden rocks on every side. The Laplanders themselves consider the situation we were in as one of the worst accidents that can ever befall them. We, however, though destitute of a guide, were fortunate enough to discover the track of a reindeer, and of some kind of carriage in which goods had probably been lately conveyed towards Norway. This track directed us safely to one of the Lapland moveable tents.

All the Laplanders are usually blear-eyed, so that one would think the word Lappi (Laplanders) was derived from lippi (blear-eyed). The causes of this inconvenience are various, but chiefly the following.[Pg 6]

1. The sharp winds. In the early part of my journey, repeated exposure to stormy weather rendered my eyes sore, so that I became unable to open them wide, and was obliged to keep them half shut. How much more must this be the case with those who dwell on the alps, where there is a perpetual wind!

2. The snow, the whiteness of which, when the sun shone upon it, was very troublesome to me. To this the alpine Laplanders are continually exposed.

3. The fogs. This day I found myself very comfortable in my walk over the icy mountain, till the fog, mist, or cloud, whichever it might be called, came about me, rendering the eyes of my interpreter, as well as my own, so weak and relaxed, that we could not open them wide without an effort. Such must often be the case with the Laplanders.

4. Smoke. How is it possible that these people should not be blear-eyed, when they are so continually shut up in their huts,[Pg 7] where the smoke has no outlet but by the hole in the roof, and consequently fills every body's eyes as it passes!

5. The severity of the cold in this country must also contribute to the same inconvenience.

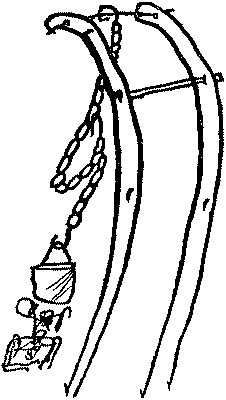

The mountain Laplanders, or those who live in the alps, build no huts; they have only tents made in the following manner.

The first figure represents two connected[Pg 8] beams, which compose the frame-work of one side of the hut; and these meet at the[Pg 9] top with two similar ones, forming the opposite side. A solitary beam is placed on each side, in the middle of the arch formed by these four, so that the whole edifice has six angles. Two more slender sticks, but equally tall, are then erected between every two angles, or main ribs, of the building. Over the whole is spread the covering of the tent (made of walmal cloth). The usual height of the structure is about a fathom and half, and the breadth two fathoms. A flap of cloth is left, so as to open and shut by way of a door, between two of the main beams.

When they lie down to rest, and are fearful of being incommoded by heat, they fix a hook through the middle of the coverlet, which raises it perhaps an ell and a half above them, and under this canopy they repose.

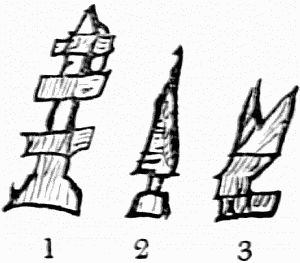

The women wear several things attached to their belt, as a leather bag, fig. 1, containing a spoon, as well as a pipe, fig. 3.[Pg 10]

Fig. 2. A knife in a case.

4. A thimble made of leather, which goes round the finger.

5. A pin-cushion, with a brass cover which pulls down over it like a cap.

6. Several large brass rings.

The belt itself is ornamented with tin or silver embroidery, and pearls.[Pg 11]

The men wear, instead of the above, a kind of bag, hanging down exactly in front. This is divided internally into two pockets, containing their tobacco-pipe, tinder-box, tobacco, and a spoon made of reindeer's horn, of an oblong flattish shape.

The women often wear a similar bag, but of a smaller size.[Pg 12]

When the reindeer are milked, as they cast their coat during the whole course of the summer, the hair flies about very inconveniently, often covering the milk in the pail. Some hair sticks also to the dugs of the animal, and it is found necessary to clean and soften them before the milking is begun. This is generally done by dipping the fingers into the milk which may be in the pail already, and washing them therewith. Whenever it happens that one of the reindeer strays from its master's herd to that of a neighbour, the person to whom it comes milks it, without any offence to the proper owner. Such an accident often happens; for these animals love society, and the more of them there are together, the better they thrive and enjoy themselves. They are marked at the ears, like cows, that every person may know his own.

The furniture of these Laplanders consists of kettles and pots, made sometimes of brass, sometimes of copper; rarely of[Pg 13] stone, on account of the weight. They have also hemispherical bowls, with handles, generally made of the hard knotty excrescences of the birch. These are often large enough to hold four or five cans, (of three quarts each,) and formed so neatly, that any one would believe them to be turned. Into these they pour what is to be served up at their meals. Plates they have none, but in their stead boards, of an oblong shape, are used for meat; which, previous to its distribution among the guests, is served up in round pails. Closely platted baskets, or tubs, always circular, are used to keep cheese in. There is moreover an oblong barrel, for the purpose of holding jumomjolk (vol. 1. p. 273).

Within the tent are spread on each side skins of reindeer, with the hairy part uppermost, on which the people either sit or lie down, for the tent is not lofty enough to allow any one to stand upright. In the centre of the whole is the fire-place, or a square enclosure of low stones about the[Pg 14] ash-heap. The back part of the tent, behind the fire-place, is entirely occupied either with brush-wood or branches of trees, behind which, or, most commonly, before it next the fire, the household furniture is placed. In the roof are two racks, suspended over the reindeer skins on each side, upon which cheeses are laid to dry, and before these, towards the entrance, hang rennet-bags, filled with milk, preserved for winter use.

The annexed figure is a sort of plan of the floor of one of these Lapland tents. a is the fire-place. b, b, reindeer skins, six in number, three at the right hand, on entering the tent, and as many at the left. c large fire-wood. d cheese-vessels. e kettle, with its lid. f, behind the first reindeer skin, is the place of the harness. g a barrel or cask. h a store of skins and hair of the reindeer. i the milk-strainer, with its flat cover.[Pg 15]

The following figure represents the roof of the tent, as seen from below. a, a, are the racks on which the cheeses are ranged. b outlet for the smoke. c, c, rennet-bags containing milk. d plat of hair from the reindeer's tail, to strain milk through. e the flat cover of the milk-strainer; see i in the former figure.[Pg 16]

Such was the dwelling, and I shall now describe some of its inhabitants. I sat myself down at the right hand of the entrance, with my legs across. Opposite to me sat an old woman, with one leg bent, the other straight. Her dress came no lower than her knees, but she had a belt embroidered with silver. Her grey hair hung straight down, and she had a wrinkled[Pg 17] face, with blear eyes. Her countenance was altogether of the Lapland cast. Her fingers were scraggy and withered. * * * * Next to her sat her husband, a young man, six-and-thirty years of age, who, for the sake of her large herds of reindeer, had already been married ten years to this old hag. When the Laplanders sit, they either cross their legs under them, or one knee is bent, the other straight.

As a defence against wind and snow, a sort of hood, called nialmiphata, is worn over the cap. It is made of red cloth, of the shape of a truncated cone, dilated at the bottom, and is four palms high, three palms in circumference at the upper part, and six at the bottom. This covers the cheeks, as well as the neck and shoulders, the eyes and mouth only being exposed. In the back part, at bottom, is a loop, through which goes a riband to secure the whole from being blown off, by being tied round the body under the arms.

In winter-time the women wear breeches, made exactly like those worn by the men,[Pg 18] as well as boots, though the latter come no higher than the knees. It is wonderful how they are able, in the severity of winter, to follow the reindeer, which are never at rest, but keep feeding by night as well as by day. They have indeed small sheds or huts, here and there, into which they occasionally drive their reindeer, but with the greatest difficulty.

During the night we passed over the beautiful lake of Wirisiar. The weather was very cold and foggy.

In the morning we arrived at the abode of Mr. Kock, the under bailiff, where I could not but admire the fairness of the bodies of these dark-faced people, which rivalled that of any lady whatever.

Here I saw some Leming Rats, called in Lapland Lummick. The body of these animals is grey; face and shoulders black; the loins blackish; tail, as well as ears, very short. They feed on grass and reindeer-moss (Lichen rangiferinus), and are[Pg 19] not eatable. They live, for the most part, in the alps; but in some years thousands of them come down into the woodland countries, passing right over lakes, bogs, and marshes, by which great numbers perish. They are by no means timid, but look out, from their holes, at passengers, like a dog. They bring forth five or six at a birth. Their burrows are about half a quarter (of an ell?) deep.

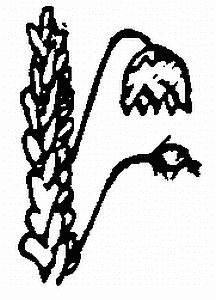

Here I found the little Gentian, or Centaury, with a hyacinthine flower in five notched segments (Gentiana nivalis).

I gathered and examined the little Catchfly, which resembles the common one (Lychnis Viscaria) except in being smaller, and not at all viscid. (L. alpina; see v. 1. p. 302. n. 46.) The root is perennial. Leaves oblong-lanceolate, approaching to linear. Stem simple, round, smooth, bearing two, three, or four pairs of opposite leaves. From the uppermost pair springs[Pg 20] one flower-stalk on each side, bearing a single flower, between two small opposite purple leaves. A little higher up, two other simple flower-stalks come forth in the same manner, with two coloured leaves at their base, the stem being thus extended straight upwards. Calyx ovate, erect, coloured, with five teeth. Petals five, their disk cloven half way down; the crown with two teeth. Stamens 10. Pistils 5.

After passing the alps, we grew thirsty; but the water we met with proved less pleasant than usual, having an earthy taste, although it flowed from plentiful stores of ice and snow. My Laplander took his knife and cut out a lump of ice, which he sucked by way of refreshment. I found this mode of drinking agreeable enough, the ice being very palatable, and we both partook of it largely. He told me it was considered very wholesome for the chest. Indeed I learned, both from the Laplanders and my own experience, that pure water, however cold, is never hurtful, provided it be taken in moderation.[Pg 21]

I was desirous of having my linen washed; but the people understood my request as little as if I had spoken Hebrew, not a single article of their own apparel being made of linen. As their food is of animal origin, so is their clothing, which consists either of skins, the produce of the country, or of the woollen cloth called walmal, which they purchase. In the winter they wear Lapland boots, which come up as high as the middle of the thighs, without any stockings, only the feet are protected with what they term Skogras (Carex sylvatica Fl. Brit.), as already mentioned. Next to the body they wear a jacket of walmal, and above that a lappmudd, or coat of reindeer skin, with the hairy side turned inwards. In summer they turn that side outwards. The boots used by the women do not reach higher than the knee.

I remarked with astonishment how great[Pg 22]ly the reindeer are incommoded in hot weather, insomuch that they cannot stand still a minute, no not a moment, without changing their posture, starting, puffing and blowing continually, and all on account of a little fly. Even though amongst a herd of perhaps five hundred reindeer there were not above ten of these flies, every one of the herd trembled and kept pushing its neighbour about. The fly meanwhile was trying every means to get at them; but it no sooner touched any part of their bodies, than they made an immediate effort to shake it off. In one respect this season is peculiarly propitious to the insect, as the reindeer's coat is now very thin, most of the hair of last year's growth being fallen off. I caught one of these insects as it was flying along with its tail protruded, which had at its extremity a small linear orifice, perfectly white. The tail itself consisted of four or five tubular joints, slipping into each other, like a pocket spying-glass, which this fly, like others, has a power of contract[Pg 23]ing at pleasure. See what I have already mentioned (vol. 1. p. 280), concerning the spots in the reindeer skins, as caused by this insect (Oestrus Tarandi).

When the Lapland children are laid into the cradle, they seldom cry, although their hands are confined down to their sides. If they cry, it is generally from hunger. The cradle is placed in a sloping position, so that the child's head is half upright. The bottom of the cradle is hollowed out of a piece of fir wood, consequently not very heavy. Over the head of the child is a hoop forming an arch, to which a transverse bow is fixed, the whole being covered with cloth, like the rest of the cradle. In summer the child lies without any covering of reindeer hair, only having under its head and body either some walmal cloth, fur, or moss.

The Laplanders use a curious kind of box or basket, which they call kisa, for keeping or carrying various articles. It is of an oval form, with the bottom and sides[Pg 24] made of fir, like a box, being about a foot and half long, a foot broad, and six inches deep, with a transverse opening in the bottom to admit a part of the saddle of the reindeer. The contents are confined by a lacing of cords, that goes from side to side across the top, which is otherwise open. Two such boxes, each weighing about two pounds, are placed like panniers upon the reindeer; for that animal cannot carry above four or five pounds weight, and the castrated males only are used as beasts of burthen at all. A leather thong crosses the saddle, connected with another longer one, which goes round the chest of the animal at one part, and round its thighs, like the breechings of a horse, at the other. A pack-saddle, made either of reindeer skin, or of walmal cloth, with a bow of spruce fir, goes across the back, and is connected with the leather thongs just mentioned, being further secured by a girth under the belly. Against the sides of this pack-saddle the above-described boxes or[Pg 25] baskets are hung and fastened, the transverse chink in the bottom of each being fitted to the saddle.

I observed that the Laplanders, both men and women, after borrowing a lighted pipe, and passing it from one to another, retain a mouthful of smoke as long as possible, that they may enjoy as much of the flavour as they can. Old men chew tobacco.

The tendons in the legs of the reindeer serve to make thread or cord. In each hind leg are two tendons, one before the other; in each fore leg one behind and two or three before it. These the Laplanders lay hold of with their mouths, split and moisten them, rubbing them from time to time with reindeer marrow, preserved in bladders for that use, in order to render them as supple as possible. Each string is made sharp at both ends, and drawn through holes of various sizes in an instrument made on purpose (of wood or metal) to render it as fine and smooth as they can. Two such threads[Pg 26] are then twisted together by means of the hand upon the thigh or knee. They are generally held with the left hand, and twisted with the right upon the left knee, proceeding downwards, the thread being moistened from time to time with saliva.

In this part of the country the Empetrum (Crow- or Crake-berry) serves for firing. Otherwise the most common fuel is the dwarf Birch (Betula nana), and the Willow with lanceolate white hairy leaves (Salix lapponum), so very abundant on the Lapland alps. The dwarf birch bears very small leaves in these elevated regions.

When the children are taken out of the cradle, which I have already described (vol. 2. p. 23), they are dressed in a small garment of reindeer skin. They are usually able to stand on their legs by the time they are four months old, and turn their head and eyes about with a degree of intelligence hardly ever seen in our children at that early age.

I never met with any people who lead[Pg 27] such easy happy lives as the Laplanders. In summer they make two meals of milk in the course of the day, and when they have gone through their allotted task of milking their reindeer, or making cheese, they resign themselves to indolent tranquillity, not knowing what to do next. In winter their food is cheese, taken once or twice a day, but in the evening they eat meat. A single reindeer supplies four persons with food for a week.

This animal has no gall-bladder, nor could I discover the insertion of the biliary duct. The liver however is of a large size. The first stomach is large, with a thick orifice, and lined with a fine cellular network like that of a cow, being moreover longitudinally plaited. The Laplanders are curious dissectors. They take out each of the stomachs separately, with as much care as a professed anatomist.

The thread made of sinews, as above described, is never used for sewing walmal, which makes their summer clothing, but only for garments composed of fur or lea[Pg 28]ther. Their shoes indeed are mended, as well as made, with it. This last business falls to the lot of the women. The leather is purchased.

A good ox may be bought in Norway for three rix-dollars; a female reindeer for one rix-dollar; a castrated male for from twelve to eighteen dollars, silver coin; and a fawn is worth from twelve to eighteen dollars of copper money. Three reindeer, therefore, are but equal to the value of a common ox.

I left this place in the evening, proceeding on my journey on foot, and walking all night long, till three o'clock in the afternoon of the following day. Thus I walked six miles at a stretch, before I arrived at another Lapland hut.

Nothing occurred particularly worth noticing by the way, except an Andromeda (tetragona) with quadrangular shoots, and[Pg 29] flowers from the bosoms of the leaves. The stem is woody, procumbent, naked, thread-shaped, variously divided. Branches partly erect, entirely covered with leaves, which are oblong, obtuse, somewhat rounded, concave, keeled, sessile, disposed in an imbricated manner. Flower-stalks solitary, from the bosoms of the leaves, erect, thread-shaped, whitish, each bearing a drooping flower. Calyx five-cleft, purplish, with ovate straight segments. Petal one, half-ovate or bellshaped, exactly resembling the lily of the valley, cut half way down into five erect acute segments. Stamens ten, very short, with horned anthers, scarcely longer than the calyx. Pistil simple, the length of the calyx. Pericarp roundish, with five obtuse angles, erect, of five cells, with several seeds[1].

The people here use a kind of bread called Blodbrod (Blood Bread), made of small fresh fish, bruised and mixed with a little quantity of flour. This is baked or roasted on a jack before the fire, but it is used only in hard times.[Pg 31]

There are no common flies, bugs, nor snakes, on these Alps.

The Laplanders however abound with lice, which in winter are allowed to freeze, when they turn red, and are easily killed. In summer they come forth from the clothes, if exposed to the sun, and are then de[Pg 32]stroyed with the nails, these people having no firelock to shoot them with[2].

I was informed that in this neighbourhood the inoculated small-pox is remarkably fatal. If the patients have but seventy or eighty pustules, they die of it as of the plague. They fly to the mountains, when infected, and die. The same is the case with the measles. It appears that both these diseases are aggravated by the violent cold, whence the patients die in so miserable a manner[3].

Swelled necks (goitres) are frequent.

Sore eyes are universal, especially in the spring, when the Laplanders remove towards the Alps. The glittering of the snow has then a pernicious effect on their eyes. Aged people are very often blind.[Pg 33]

Female obstructions are rare, though sometimes met with among the better sort of people; neither are the catamenia immoderate, nor in common so copious as with us. The Lapland women are entirely ignorant of the leucorrhœa.

Of hysterics I met with but two cases. One maid-servant, twenty-four years of age, had the complaint about once a year; another, about thirty, was attacked with it monthly during the summer.

Epilepsy sometimes occurs. Headachs are frequent; hence the forehead is often seen full of scars (from the application of their toule, or moxa; see vol. 1. p. 274).

Elderly people are often hard of hearing.

The sleep of the Laplanders is commonly sound, and they are in the habit of sleeping or waking whenever they please.

A swelling, or falling down, of the uvula is not uncommon, in which case they frequently cut off the part affected.

When children are troubled with swellings in the glands about the throat, the[Pg 34] usual remedy is to prick the part, and suck out the blood, which is considered as a speedy and effectual cure. If this method be not adopted, they suppose the blood would rise to the head, and cause cutaneous eruptions there.

Coughs are of very rare occurrence, notwithstanding the constant practice of drinking snow- and ice-water, even after swallowing pure grease or fat, which perhaps may prevent its bad consequences. However this may be, the Laplanders seldom die from catching cold. Cases of phthisis, or consumption, do indeed now and then occur among them, and pleurisies are very common, especially in spring and autumn. Lumbago, or pain in the back, is most prevalent during the summer. For this, as I have already mentioned, vol. 1. p. 274, actual cautery, by means of their toule, or moxa, is often applied.

Bleeding at the nose chiefly happens among those Lapland women who are in the service of the colonists, and who, in[Pg 35] consequence of certain obstructions, are subject also to œdematous swellings of the feet.

I have not heard of a single instance of jaundice.

Some elderly people are afflicted with asthma; and hoarsenesses now and then occur in the winter and spring.

The stone and gout are entirely unknown amongst the Laplanders.

Swellings of the lower extremities are uncommon, as these people are in the habit of swathing their legs, which renders them all slender and well shaped. All dropsical complaints indeed are very rare, though I did meet with one case of this kind.

Of tenesmus I happened to hear of but a single instance, though the Laplanders eat so much cheese and drink water.

Disorders in the stomach are not uncommon, which are frequently attended with diarrhœa, and in some years this disease is contagious.

The specimens of minerals which I had[Pg 36] collected in the course of my tour were now become numerous, and consisted of the following articles.

1. An alum, as I presume, of a club shape, without any taste, seeming as it were dissolved in fluor, from the mountains to the north of the lake Skalk, near Kiomitis. (See vol. 1. p. 267.)

2. Native alum in its own matrix; from the same place. (Alumen nativum. Syst. Nat. vol. 3. 101).

3. Native alum, rough and green, separate from its matrix; from the same mountains.

4. Alum like the former in appearance, but not salt, perhaps a calcareous stone; found not far from the same place.

5. Various alpine micaceous stones.

6. Marle from Lapland.

7. Quartz from Lapland.

8. Silver ore from Kiurivari.

9. Silver ore from Nasaphiel in Pithœan Lapland.

10. Sandstone containing three per cent. of iron.[Pg 37]

11. Black slate from the alps.

12. Petrified corals from Norway.

13. Iridescent fluors from the alps.

The fish called by the Laplanders Sijk (the Gwiniad, or Salmo Lavaretus,) is taken in their lakes. Its head terminates in an obtuse point. The upper jaw is the longest. Mouth without teeth. Iris of the eye silvery, with a blackish upper edge, and a black pupil. The whole body is silvery, blackish about the back, eleven inches long and two deep. Head two inches long at the sides; from the snout to the dorsal fin four inches and a half. The dorsal fin consists of thirteen rays, of which the first is by far the largest, and the last cloven or interrupted. The soft fat fin is in its proper place.

The following are the disorders or inconveniences to which the reindeer are subject.

When the frost is so intense as to form an impenetrable crust on the surface of the[Pg 38] snow, so that the animal cannot break it with his feet, to get at the Lichen on which he feeds, he is frequently starved to death. This misfortune is as dreadful to the Laplanders as any public or national calamity elsewhere; for, when his reindeer are killed, he must himself either starve to death, beg for his livelihood, or turn thief.

The hoofs of the reindeer are not uncommonly affected with a swelling at the edge where they are attached to the skin, at which part they consequently become ulcerated, and are seldom healed. The creature thus grows lame, and cannot keep up with the herd.

These animals are sometimes attacked with a vertigo, or giddiness in the head, which causes them to run round and round continually. The people assured me, that such of them as run according to the course of the sun may be expected to get the better of the disorder; but those which turn the contrary way, being supposed incurable, are immediately killed. The reco[Pg 39]very of the former is thought to be promoted by cutting their ears, so as to cause a great discharge of blood.

The Kurbma, or ulceration caused by the Gad-fly, (see vol. 1. p. 280.) takes place every spring, especially in the younger fawns. Such as are brought forth in the summer season are free from this misfortune the ensuing spring, but in the following one many of them lose their lives by it. When come to their full size and strength, the consequences are less fatal; but no reindeer is entirely exempt from the attacks of this pernicious insect.

The fawns are of a reddish hue the first season, during which they cut their foreteeth. In the autumn they turn blackish, and have fodder given them. They are when young frequently afflicted with a soreness in the mouth, so as to be unable for a while to eat.

Reindeer are subject to a disease called by the Laplanders Pekke Kattiata, accompanied with ulcerations of the flesh, which[Pg 40] however often heal by a sloughing of the part affected. This is an epidemic disorder. It is believed that if any of the ulcerous part, which is cast off, be swallowed by the animal, in licking his own coat, or that of any other of the herd labouring under this malady, it proves fatal by corroding the viscera.

The dugs of the female often become chapped or sore, so as to bleed whenever they are milked.

The male reindeer in his natural state is fatter than such as are castrated, except the latter be kept without work, in which case they become the fattest. Such as are castrated and allowed to run wild, become considerably larger, as well as tamer, in consequence.

The rutting season lasts but a fortnight, that is, from about a week preceding the feast of St. Matthew (Sept. 21.) to Michaelmas day, during which period the male is savage and dangerous. Immediately afterwards he casts his coat and horns,[Pg 41] and not unfrequently becomes so emaciated, that, in many instances, death is the consequence.

Towards the feast of St. Eric (May 18.) in the following year, or within a fortnight of that period, very rarely later, the females bring forth their young. They do not copulate the first year, and seldom before the third, their progeny being found the better for this delay. Indeed neither the males nor females arrive at their full growth and perfection before they are towards three years old.

The fawn, whether male or female, is called the first year mesk; the second season the male is called orryck, and the female whenial. In the third year the latter, if she has been covered, is known by the appellation of watja or waja, which means a wife; if otherwise, she goes by the name of whenial-rotha, the three-year old male being called wubbers. In his fourth year the male is termed koddutis; in the following one kosittis; in the sixth machanis, and in[Pg 42] the seventh namma lappotachis. After that period no male is kept, they all perishing in consequence of the exhaustion above mentioned, but the castrated ones live to a more advanced age. None of these animals however survive beyond their twelfth or fourteenth year. When the castrated males become very fat towards autumn, and show signs of old age; or the females, having become barren, appear otherwise to be on the decline, they are killed, by the knife, in the close of the year; from an apprehension that they might otherwise perish of themselves from infirmity, in the course of another season.

Such of the male reindeer as are destined to serve for a stock of provision, are killed before the rutting-time, and their carcases hung up to be exposed to the air and frost before flaying. The flesh is smoked and a little salted, and then laid upon sledges to dry in the sun, that it may keep through the winter till spring. About the feast of St. Matthias (Feb. 24.) the reindeer begin[Pg 43] to be so incommoded with the gad-fly, that they are not in a fit condition to be slain for eating. From that period therefore, till the milking season, the Laplanders are obliged to live on this stock of preserved meat. At other times of the year the females are killed for immediate use, according as they are wanted. The blood is kept fresh in kegs, or other vessels, and serves for food in the spring, being added to the välling (see vol. 1. p. 129), with a small proportion of milk and water. The blood of these animals is thick in consistence, like that of a hog. The Laplanders carry a portion of it along with them from place to place, in bladders or some kind of vessels. A stock of this and all other necessaries is collected as late as possible, before the melting of the snow, while there still remains a track for the sledges.

A kind of blood pudding or sausage is made, in general without flour, and with a large proportion of fat. This the Laplanders call marfi.[Pg 44]

The liver of the reindeer, which is of a considerable bulk, is boiled and eaten fresh. The lungs, being salted and moderately dried, are eaten occasionally, or else given to the dogs. The intestines, which abound with fat, are cut open, washed, and boiled fresh; nor are they unpalatable. The brain and testicles are never eaten. The foot is flayed down to the fetlock joint, beyond which the hair cannot, by scalding or any other contrivance, be separated, without the cuticle and skin coming along with it. Even when the feet are boiled, the hair never comes off without the skin. Thus the animal when living is the more firmly protected against the snow. The hoofs are thrown away as useless.

The dung of the reindeer in summer is almost as large as cow-dung, but in winter it more resembles that of the goat.

Each individual reindeer does not bear horns of precisely the same shape every year. The points are very liable to be deformed, in consequence of the animal's[Pg 45] scratching them, while in a growing state, with its feet; they being in that state much inclined to itch, and as tender as the flesh of a fresh fish.

These animals are afflicted with maggots called kornmatskar in their noses and gums, from which they relieve themselves in the spring by snorting and blowing. When the insects lodge on their backs and form pustules there, the people make a practice of squeezing them out, to prevent the reindeer from being too much irritated by them. (This species is the Oestrus nasalis, though the account here given is not very clear; but in the first edition only of the Fauna Suecica Linnæus says, on the authority of a gentleman named Friedenreich, that "this Oestrus lodges its eggs in the frontal sinus of the reindeer in Lapland, and is frequently cast out by them as they travel along in the spring.")

When the skin is stripped from the carcase of the reindeer, it is immediately spread out, and stretched as much as pos[Pg 46]sible, by means of a longitudinal pole, and a transverse stick at each end of the skin, these sticks being pulled asunder with a strong cord. Several more transverse twigs are placed between these two sticks, so as to extend every part of the edges of the hide, which in this position is allowed to dry.

The Laplanders' gloves are made of skin taken from the legs of the animal; their hairy shoes, of that from its forehead between the horns, such being worth two dollars, copper money; while those made from the skin of the legs, being much thinner, are of very little or no value.

A Laplander never goes barefoot, though he has nothing to serve him for stockings but hay (Carex sylvatica, Fl. Brit.). Sometimes he buys leather for shoes or boots from his neighbours.

The people of this country boil their meat in water only, without any addition or seasoning, and drink the broth. Jumomjölk (see vol. 1. 278.) kept for a whole[Pg 47] year is delicate eating. Berries of all kinds are boiled in it. Some persons make a practice of boiling those berries by themselves, preserving them afterwards in small tubs, or other wooden vessels. They boil their fish more thoroughly than their meat, over a slow fire, drinking likewise the water in which it has been drest. The meat is never so much boiled as to separate from the bone. Fresh fish is sometimes roasted over the fire. Few people dry and salt it, though that method is sometimes practised. Meat is dried by the air, sun and smoke all together, being hung up in the chimney, or rather hole by which the smoke escapes through the roof.

The Laplanders never eat of more than one dish at a meal.

By way of dainty, the women occasionally mix the berries of the Dwarf Cornel (Cornus suecica) with Kappi (see vol. i. p. 281.), which is made of whey boiled till it grows as thick as flummery. To this they[Pg 48] moreover add some cream. That fruit is entirely neglected in the country of Medelpad.

In Dalecarlia the people generally keep their cattle up in the mountains, twelve or sixteen miles from their own dwellings, on account of gad-flies and other stinging insects. There they have their dairies, and make cheese. The remaining whey is boiled till two thirds are wasted, when it becomes as thick as flummery. This is sometimes eaten instead of butter, sometimes mixed with dough, or serves for food in various other manners.

The wind is excessively powerful in this alpine region, so that sometimes it is impossible to stand against it, both men and sledges being overturned by its violence.

It blew so hard at the place where I now was, that one of the windows of the curate's house was blown in upon the floor.

Every Laplander constantly carries a sort of pole or stick, tipped with a ferule,[Pg 49] and furnished with a transverse bit of wood. Whenever he is tired, he leans his arms and nose against it to rest himself.

Such as live in the forests are dexterous marksmen, but not those who inhabit the alps. Nevertheless, they all contrive, by means of their wooden bows, to procure, in the course of the winter, a considerable number of Squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris) in their grey or winter clothing, for the sake of their skins.

In the winter season also they go in pursuit of their most cruel enemies the wolves. One of these animals will sometimes kill twenty or thirty reindeer at a time, if he comes into the enclosure where they are. The wolf often runs away before the Laplander can get near enough to fire at him. A bear can hardly catch a reindeer, except by coming upon it unawares, the latter being much the most swift of foot; but if he gets into any of the store-houses, he does a great deal of mischief, turning every thing topsy-turvy. Bears are also[Pg 50] very dangerous in the fissures of rocks and mountains, where they usually conceal themselves.

The Glutton (Mustela Gulo) does most harm in the pantry or store-house. He never meddles with the reindeer.

A part of the employment of the men is to make sledges, or other machines of wood for carriage. They cut rough wood in the forests for the boxes which they carry with them into the alps.

The duty of the women is to mend the clothes of the whole family.

Laplanders have several plays or amusements.

Children make of the dwarf birch (Betula nana) something like reindeer's horns, with which they gore one another in sport. They amuse themselves frequently by building little huts of stone.

Grown-up people play very well at tennis, but they seldom partake of that diversion. More common amusements are blindman's buff, and drawing gloves.[Pg 51]

Here I think it worth while to observe, that the alpine Laplanders are more honest, as well as more good-natured, than those who dwell in the woodlands. Having acquired more polish from their occasional intercourse with the inhabitants of towns, the latter have, at the same time, learned more cunning and deceit, and are frequently very knavish. The inhabitants of the alps dwell in villages formed of their tents, living together, as I have already related, in great comfort and harmony. Those who occupy the woody parts of the country live dispersed.

The Laplanders know no musical instrument except the lur (a sort of trumpet), and pipes made of the bark of the quicken tree or mountain ash. They are not accustomed to sing at church, except those who are reckoned among the great or learned of the community.

The inhabitants of this country are not more troubled with chilblains than those of other places. They do not mind[Pg 52] having their cheeks frost-bitten. The women wear an embroidered band round the head, which affords no protection in this respect; but the men have a loose band of skin with the hair on, which can be pulled down occasionally over their cap, when the cold is intolerable.

(But to proceed with a further account of the diversions of the people I am describing).

Spetto, one of their games, is played, by men as well as women, in the following manner. They prepare from thirty to fifty or sixty pieces of wood, a hand's breadth in length, which are spread upon the extended skin of a reindeer. One of the players takes a ball made of stone or marble, larger than a boy's playing marble, which he throws up into the air about an ell high. While the ball is up, he snatches away one of the sticks, but in such a manner as not to miss catching the ball in its fall, holding the stick in the same hand. He subsequently gathers together,[Pg 53] in his other hand, as many of the sticks as he has thus been able to procure. If he fails in any respect, another person is to take the ball, and proceed in the same manner, the former player resigning up to him one of the sticks every time the ball is thrown, till no more remain in his own possession. He who can take up all the sticks wins the game.

The following rules are to be observed.

1. He who catches the ball, but not one of the sticks, must resign the ball to another player, as well as he who has let it fall.

2. He who takes up more than one stick at a time, must return what he has taken.

3. The adversary, that is, the last player, who could not succeed in taking up all the sticks, is allowed to lay down as many as he pleases of the sticks he has collected, and may arrange them according to his fancy. It is usual to lay one upon another, in order to render the game more difficult, the player being obliged to[Pg 54] snatch up each separately; which is not easy without taking two, when so situated, at once.

4. When at length one person has taken up all the sticks, his adversary is permitted to replace the two last of them upon the skin in any manner he chooses. He commonly separates them as widely as possible. The person who had previously gained the whole, is then required to take up both these sticks at one throw of the ball, and if he fails he must give up the game. Thus the victory is often lost by means of these two last sticks.

5. When the adversary fails of his aim, the other player is to take all the sticks lying on the field, as well as those which, after having been laid down by himself, were won by the other person, and the whole are to be laid down again directly, in order to be taken up according to the above rules. But he is no longer under any obligation himself to take up the sticks which he has thus laid for his companion.[Pg 55]

The game called Tablut is played with a checkered board, and twenty-five pieces, or men, in the following manner.

Fig. 1, is the king, whose station is in the central square or royal castle, called konokis by the Laplanders, to which no other person can be admitted.

Fig. 2, represents one of the eight Swedes his subjects, who, at the commencement of the game, are stationed in the eight squares, adjoining to the royal castle, marked 2 and 3.

Fig. 3, is one of sixteen Muscovites, their adversaries, who occupy the sixteen embroidered squares, (some of them marked 4 in the cut,) situated four together in the middle of each side of the field.

The vacant squares, distinguished by letters, may be occupied by any of the pieces in the course of the game.

1. Any piece may move from one square to another in a right line, as from a to c; but not corner-wise, or from a to e.

2. It is not allowed to pass over the heads[Pg 57] of any other pieces that may be in the way, or to move, for instance, from b to m, in case any were stationed at e or i.

3. If the king should stand in b, and no other piece in e, i, or m, he may escape by that road, unless one of the Muscovites immediately gets possession of one of the squares in question, so as to interrupt him.

4. If the king be able to accomplish this, the contest is at an end.

5. If the king happens to be in e, and none of his own people or his enemies either in f or g, i or m, his exit cannot be prevented.

6. Whenever the person who moves the king perceives that a passage is free, he must call out raichi, and if there be two ways open, tuichu.

7. It is allowable to move ever so far at once, in a right line, if the squares in the way be vacant, as from c to n.

8. The Swedes and the Muscovites take it by turns to move.

9. If any one man gets between two squares occupied by his enemies, he is killed and taken off, except the king, who is not liable to this misfortune.[Pg 58]

10. If the king, being in his own square or castle, is encompassed on three sides by his enemies, one of them standing in each of three of the squares numbered 2, he may move away by the fourth. If one of his own people happens to be in this fourth square, and one of his enemies in number 3 next to it, the soldier thus enclosed between his king and the enemy is killed. If four of the enemy gain possession of the four squares marked 2, thus enclosing the king, he becomes their prisoner.

11. If the king be in 2, with an enemy in each of the adjoining squares, a, A and 3, he is likewise taken.

12. Whenever the king is thus taken or imprisoned, the war is over, and the conqueror seizes all the Swedes, the conquered party resigning all the Muscovites that he had taken.

The Laplanders use the middle bark of the elm for dressing their reindeer skins, but merely by chewing it, and rubbing their saliva on the skins.

They also tan with birch bark, but do not suffer the skins to remain long under[Pg 59] the operation, which they say would render them rotten and apt to rend, neither can they spare them very long.

White walmal cloth is procured from Russia, but for want thereof they commonly wear a light grey cloth of the same kind.

Ropes are made of roots of spruce fir in the following manner. Choosing the most slender roots, they scrape off the bark, while fresh, with the back of a knife, holding the roots against the thigh. Afterwards each root is first split with the knife into three or four parts, which are then by degrees separated into a number of very slender fibres; and these, being wrapped round the hand like a skain of thread, are tied together. They are then boiled in a kettle for an hour or two, with a considerable quantity of wood ashes. While still soft from this boiling, they are laid across the knee, and scraped three or four times over with a knife. At last they are twisted into small ropes. Birch roots serve in like manner to afford cordage for the Laplanders, but more rarely. The[Pg 60] latter are more generally used, without being split, for basket-work. For various articles of furniture the roots of Tall (Scotch Fir, Pinus sylvestris) are cut into small boards. The wood of that tree serves for inferior kinds of work, and, amongst other things, for cheese-vats.

The Laplanders scrape with a knife the young and tender stalks of the plant called Jerja, (Sonchus alpinus, Sm. Plant. Ic. t. 21.) and eat them as a delicacy, like those of the great Angelica (A. Archangelica), which in the first year of their growth are termed Fatno.

A Laplander always places himself at the further part of his hut, and his guest is seated next to him on a skin spread on purpose. The master of the hut is by this means enabled to reach the vessel in which water is kept for drink, and which always stands in the upper part of the hut.

The river Hyttan flows in a perpetual stream both summer and winter. Now if, according to the general opinion, the water of this river were derived from exhala[Pg 61]tions of the great ocean, collected by the alps of this country, it should cease to run when all the alpine tracts are frozen. The stream must therefore be constantly fed by neighbouring springs.

The names by which the Laplanders distinguish the several times of the day or night are as follows.

Midnight is called in their language kaskia. The remainder of the night before dawn, pojela kaskia. The morning dawn, theleeteilyja. Sun-rise, peivimorotak. Two or three hours after sun-rise, areiteet. The hour of milking the reindeer, which is about 8 or 9 o'clock, arrapeivi. Noon, or dinner time, kaskapeivi. About 5 or 6 o'clock in the afternoon, eketis peivi. Sunset, peiveliti. Night, iä.

The days of the week are named as follows.

Sunday, Sotno peivi.

Monday, Mannutaka.

Tuesday, Tistaka.

Wednesday, Kaska vacku, or middle of the week.[Pg 62]

Thursday, Tourestaka.

Friday, Perietaka.

Saturday, Lavutaka.

They have no names for the months, but certain weeks are distinguished by the following appellations.

Midsummer week, Midtsomarvacku.

St. Peter's week, June 29, Pelasmassu vacku.

Goose week, Gassa vacku.

In the middle of the summer, Gaskakis.

St. Margaret's, July 20, Marcrit.

St. Olaus' mass, July 29, Vollis.

(No date mentioned here.) Vehak.

St. Laurence, Aug. 10, Lauras.

Reindeer-fawn week, Orryk. When in a fawn two years old the horns begin to bud.

St. Bartholomew, Aug. 24, Barti.

(No date.) Hoppmil.

St. Mary, Sept. 8, Margi.

Holy Cross, Sept. 14, Behawis.

St. Matthew, Sept. 21, Matthus.

St. Michael, Sept. 29, Michel.

(St. Faith, Oct. 6?) Perkit.

(Middle of Oct.) Talvi.

The annexed figure represents a Laplander's staff. It is tipped with a blade of iron, as thick as the thumb. With this weapon he attacks the bear and wolf in the time of deep snow. On the lower part of the shaft is a sort of hoop, six inches in diameter, made of root of fir, and fastened with thongs of reindeer skin, one of which passes through a hole in the staff. At the bottom it is mounted with iron. The use of this hoop is to prevent the staff from sinking into the snow, when used as a walking-stick. The shaft itself, made of birch wood, is about four feet long, and an inch and half thick.[Pg 64]

This sketch is taken from one of their snow shoes, made of wood. Its length is six feet, from h to i; breadth, from k to g, five inches. The hind part, i, is rather more obtuse than the other end, h, which last is elevated about two or three inches. From h it gradually widens to f. The part from c to d, where the foot stands, is about eight inches; its breadth three. The under part of the shoe is convex, and furrowed lengthwise; the upper flattish, raised about ten lines, and the edge all round is sharp. At b is a band, made of fir root twisted, serving to tie the shoe fast round the ancle. The general thickness of the shoe throughout is from three to four lines.[Pg 65]

Some people wear a pair of the same size; others have the left shoe smaller than the right. Each is often lined or covered, about the central part, with a piece of hairy reindeer skin, to prevent the foot slipping about upon the shoe, and give a firmer step in walking over the snow. This is most practised in Kimi-Lapmark, where the wild reindeer are most abundant.

The Lapland thread is made out of the tendons of reindeer fawns half a year old. Such thread is covered with tin foil for embroidery, its pliability rendering it peculiarly fit for the purpose. The tendons are dried in the sun, being hung over a stick. They are never boiled.

To show to what a high degree of perfection these people have arrived in the art of making such thread, I brought away a sample of it, which I believe none of our ladies could match.

Shoes and baskets made of birch bark are used both in Angermanland and Hel[Pg 66]singland, as well as ropes of the same material, which will not sink in water, but these are not in general use.

The bows which serve the Laplanders for shooting squirrels are composed of two different kinds of wood, laid parallel to each other. The innermost is birch, the outermost of what they term kior, kioern or tioern. (This is procured from a tree of the Common Fir, Pinus sylvestris, that happens to grow in a curved form, usually in marshy places, or on the banks of rivers, and whose contracted side is hard like box: see vol. i. p. 255; also Fl. Lapp. n. 346, λ.) If this be not practised, the bows are more apt to snap. Each layer of wood is externally convex, yet not so much as to render the bow quite cylindrical.

When the Laplanders expect any visitors, they are particularly careful to have plenty of ris (branches of the dwarf birch) spread on the floor, under the reindeer skins on which they sit; otherwise they would be thought deficient in civility, and the mis[Pg 67]tress of the family would be censured as a bad manager, when the guests returned to their own homes.

The mode of their entertainment is as follows.

First, if the stranger arrives before their meat is set over the fire to boil, they present him either with iced milk, or with some kind of berries mixed with milk, or perhaps with cheese, or with kappi, (see vol. i. p. 281.) Afterwards, when the meat is sufficiently cooked, and they have taken it out of the pot, they put into the water, in which it has been boiled, slices of cheese made of reindeer milk. This is a testimony of hospitality, and that they are disposed to make their guest as welcome as they can. They next serve up some of their dry or solid preparations of milk.

The marriages of the Laplanders are conducted in the following manner. (This subject was treated in vol. i. p. 276, like Sterne's "history of the king of Bohemia and his seven castles," no doubt to the[Pg 68] great dismay of the curious reader. We ought to have warned him of its being resumed in a subsequent part of the work, but in truth we had not then ourselves proceeded so far in deciphering the original manuscript.)

1. In the first place the lover addresses his favourite fair-one in a joking manner, to try whether his proposal be likely to prove acceptable or not. Perhaps he even goes so far as to speak once or twice to her father upon the subject. He then takes his leave, either fixing a time for his return, or not, as it may happen.

2. The lover next takes with him such of his nearest relations as live in the neighbourhood, who, as well as himself, all carry provisions with them, to the hut of his mistress, he going last in the procession.

3. When the party arrive at the place of their destination, they all, except the lover, walk in. If there happen to be any other huts near at hand, it is usual for the damsel to retire to one of them, that she[Pg 69] may not be obliged to hear the conversation of the visitors. Her admirer either remains on the outside of the door, amongst the reindeer, or goes into some neighbouring hut. There are usually two or three spokesmen in the party, the principal of whom is called Sugnovivi. When they are all seated, the young man's father first presents some brandy to the father of the young woman; upon which the latter asks why he treats him with brandy? The former replies, "I am come hither with a good intention, and I wish to God that it may prosper." He then declares his errand. If the other party should not be favourably inclined to the proposal, he rejects it, at the same time thanking the person who made it. Upon this, all who are present endeavour to prevail upon him to give his consent to the marriage. If they succeed, or in case the offer has from the first been accepted, the friends of the lover fetch whatever they have brought along with[Pg 70] them, consisting of various utensils, and silver coin, which they place on a reindeer skin, spread in the hut, before the father and mother of the intended bride. The father or the mother of the bridegroom then distributes the money between the young woman and her parents. If the sum be thought too small, the latter ask for more, and it frequently happens that much time is spent in bargaining, before they can come to a conclusion. When the parties concerned cannot obtain so large a sum as they think themselves entitled to, they often reject the whole, and return the money to those who brought it. But if, on the contrary, matters are brought to a favourable conclusion, the parents allow their daughter to be sent for. Two of the bridegroom's relations undertake this office. If the bride has any confidential female friend, or a sister, they walk arm and arm together; and in this case the mother of the bridegroom is required to make a pre[Pg 71]sent of a few brass rings, or something of that kind, to this friend or sister, who keeps lamenting the loss of her companion.

When the bride enters the hut, her father asks whether she is satisfied with what he has done? To which she replies, that she submits herself to the disposal of her father, who is the best judge of what is proper for her. The mother of the bridegroom then presents the bride with the sum allotted for her, laying it in her lap. If it proves less than she had expected, she shows her dissatisfaction by various gestures, and signs of refusal, in which case she may possibly obtain at least the promise of a larger sum. All these gifts become her own property.

When such pecuniary matters are finally arranged, the father and mother of the bridegroom present him and his bride with a cup of brandy, of which they partake together, and then all the company shake hands. They afterwards take off their caps, and one of the company makes an oration,[Pg 72] praying for God's blessing upon the new-married couple, and returning thanks to him who "gives every man his own wife, and every woman her own husband."

The parents of the bridegroom next partake of some brandy, and the whole stock of that liquor which they had brought with them is fetched for the company.

All the relations of the bridegroom then come forward with their provisions, which generally consist of several cheeses, and a piece of meat dried and salted. The latter is roasted before the fire, while the company is, in the mean while, regaled with some of the solid preparations of milk, the bride and bridegroom eating by themselves, apart from the rest.

Two stewards are next chosen, one of them from the bride's party, the other from that of the bridegroom. The last-mentioned party are then required to furnish a quantity of raw meat, amounting to about a pound and half to each person. This the stewards immediately set about[Pg 73] boiling, and their duty moreover is to serve it round to all present. This meat is dressed in several separate pots, two only in each hut, if there be any neighbours whose huts can serve to accommodate the party on this occasion; for each Laplander has never more than one hut of his own. The fat part of the broth is first served up in basons. Afterwards various petticoats or blankets, of walmal cloth, are spread on the floor, by way of a table-cloth, on which the boiled meat is placed. The chief persons of the company then, as many as can find room, take their places in the hut of the bride's family, sitting down round the provision, while the children and inferiors are accommodated in the neighbouring huts. Grace is then said. The bride and bridegroom are placed near together, for the most part close to the door, or place of entrance. They are always helped to the best of the provision. The company then serve themselves, taking their meat on the points of their knives,[Pg 74] and dipping each morsel into some of the fat broth, in which the whole has been boiled, before they put it into their mouths. Numbers of people assemble from the neighbourhood, to look in upon the company through the door; and as they expect to share in the feast, the stewards give them two or three bits of meat, according as they respect them more or less. What remains after every body is satisfied, is put together, and wrapped up in the blankets or cloths, that part of it which is left by the new-married couple being kept separate from the rest, as no other person is allowed to partake of their share. The dinner being over, the whole company shake hands and return thanks for their entertainment. They always shake hands with the bride and bridegroom in the first place, and then with the rest, saying at the same time kussl[)a]n.

After taking some brandy, the whole party go to bed. The herd of reindeer had been turned out to pasture from the[Pg 75] time when the meat was put into the pot. The bride and bridegroom sleep together with their clothes on.

When the company rise in the morning, if the bridegroom's father and their party have any thing left, they treat the others with it; for the family of the bride have seldom any preparation made, not expecting, or not being supposed to expect, such company, and they never keep any brandy by them, but purchase it for every occasion. Whatever cold meat therefore remains is brought forward, to which the bride's party indeed add cheese, and any other preparation of milk they may have in store, as well as any dried meat; such things being usually kept by them. With these the party regale themselves by way of breakfast. Afterwards the family of the bride boil some fresh meat, as a final repast for their guests, who, after partaking of it, take their leave.

The banns are usually published once. The marriage ceremony, which is very[Pg 76] short, is performed after the above-mentioned company is departed. This being over, the bridegroom either takes his wife immediately home with him, or he goes to his own hut alone, and stays there from one to five days, after which he returns to her residence, bringing with him his herd of reindeer, and stays there for some time with her.

Such of the Laplanders as are rich enough to afford it, make their wives a present of a coverlet; a petticoat made of cloth, without any gathers, as usual among these people; a small silver beaker or cup; several rix-dollars and silver rings; a spoon, &c.; so that many a bride costs her husband more than a hundred dollars, copper money. To the mother he perhaps gives a silver belt, as well as a cloth petticoat.

I have already mentioned that the Laplanders eat Angelica (sylvestris) in a raw state. This plant, which the inhabitants of Westbothland call Bioernstut, has so many names among the Laplanders, ac[Pg 77]cording to the different stages of its growth, as to cause much confusion to a stranger. The first year of its growth they term the root Urtas, and the leaves Fadno; but the second year the plant is known by the name of Posco or Botsk. When the stalk is dried, or eaten raw, they call it Rasi, that is, grass. They say, when any one has eaten more of this plant than is good for him, "Elli rasi ist purro etnach," the meaning of which is, "Thou hast overloaded thyself with such a quantity of grass."

Another herb of which they are very fond is the Sowthistle with a simple stem, known by the name of Jerja. (Sonchus alpinus. Fl. Lapp ed. 2. 240. Sm. Pl. 1c. t. 21. S. lapponicus. Willd. Sp. Pl. v. 3. 1520.) This has a perennial root. The stem is erect, round, green, smooth, except a few soft scattered hairs, which are most remarkable towards the top and bottom, and is almost as tall as a man. Leaves about twelve or fourteen, half clasping the stem, gradually smaller upwards, nearly[Pg 78] the shape of Dandelion, or of the common Sowthistle, one half of each leaf, consisting of the terminal lobe, making exactly an acute triangle, toothed at the edges; from that part downwards the leaf contracts, but not to the main rib, and then again expands into two narrow appendages, as it were, equal in breadth, but unequal in length, which are crenate at their edges. From thence begins the stalk of the leaf, which is winged and toothed, and half embraces the stem. The leaves are thin and smooth, with a rib purple on the upper side, and the upper ones are the least divided, as well as the bluntest. The flowers are collected into a corymbus, somewhat like Butterbur, but more loosely, especially in the lower part, each supported by a very short stalk, accompanied by a very narrow oblong leaf which extends beyond the flower. The calyx consists of several oblong, narrow, acute, imbricated leaves, varying in number from fourteen to twenty, the outermost gradually shortest, but the[Pg 79] ten innermost are equal in length, and blunter than the rest, composing two rows; the calyx altogether is shorter than the corolla, tubular, swelling, and downy. Florets equal in number to the leaves of the calyx. Germen short, square, crowned with long white radiating down. Petal flat, cut away on one side, violet-coloured, five-toothed. Stamens five, white, their apex (anther) cylindrical, five-sided, white, marked with five blue lines. Pistil one, forked at the top. Receptacle naked, dotted. This plant grows among trees at the sides of mountains, along with the narrow-hooded Aconite (Aconitum lycoctonum), flowering at the end of July or beginning of August. The stem, which is milky, is eaten by the Laplanders in the same manner as Angelica. The taste was to me very bitter, but the people of the country do not find it so, though they confessed that it appeared bitter to them when they first learned to eat it. As soon as the plant[Pg 80] shows its flowers, the stalk becomes woody, and no longer eatable.

The sinews of which the fine thread is made that, when covered with tin, serves for embroidery, and is called tentråd (tin-thread), are taken from the feet of the reindeer, or of oxen, boiled; though sometimes the feet of sea-fowl are chosen for this purpose. Old women and girls are employed in preparing this thread, by drawing it through holes made in a piece of reindeer's horn. They wind it round their hands and feet as they form it, and smear it with fat extracted from the foot of the animal, to make it more supple, as they proceed.

Hay is made in different modes in various parts of Sweden. In Westbothland the fresh-cut grass is heaped together over night, that it may get a heat. Next day it is spread out, and by this method its quality is supposed to become richer and stronger. The same is practised with hops[Pg 81] in Jamtland, where the fresh-gathered hops are packed together, as hard as possible, till they become warm; after which they are spread out to dry. Their strength is by this means improved.

The people of Scania having mowed their grass, let it lie till dry, when they rake it together.

The Smolanders dry it in a kind of shed.

The East Gothlanders range it in heaps, two and two together, in a long row.

In Upland the new-mown grass is tied up in bundles, and collected into cocks.

In Angermannia the whole year's crop is laid by upon a kind of raised floor.

In Westbothland, after being dried in the shed, the hay is kept there for use, being laid crosswise, and cut when wanted[4].

This evening I took leave of the alpine[Pg 82] part of Lapland, and returned by water from Hyttan towards Lulea.

The White, or Mountain, Fox (Canis lagopus) lives among the alps, feeding on the Lemming Rat or Red Mouse, (Mus Lemmus,) as well as on the Ptarmigan (Tetrao Lagopus). This White Fox is smaller than the common kind. The Ptarmigan, which the Laplanders call Cheruna, feeds on the Dwarf Birch (Betula nana), which for that reason is called Ryprys, or Ptarmigan-bush. At night this bird lies squat upon the snow, in the same posture as the Wood Grous (Tetrao Urogallus, see vol. 1. 179): hence a great deal of its dung is seen in the prints it makes in the snow. This mode of roosting renders the Ptarmigan an easy prey to the Fox.

The Lemming or Red Mouse, see p. 18, (Mus Lemmus,) in some seasons entirely overruns the country; devouring the corn and grass: but though these animals thus occasionally appear by millions at a time, they subsequently depart and disappear as unaccountably, so that nobody knows what[Pg 83] becomes of them. They do no mischief in the houses.

The Ermine (Mustela Erminea) is white in winter, red in summer. This animal is seldom met with on the alps, but is very plentiful in the forests. Foxes and Wolves have destroyed the chief of the Hares. The Wolves indeed kill the Foxes.

The Shrew Mouse (Sorex araneus) and Common Small Mouse (Mus Musculus) are found in Lapmark, but no Rats (Mus Rattus).

Hunting the Bear is often undertaken by a single man, who, having discovered the retreat of the animal, takes his dog along with him and advances towards the spot. The jaws of the dog are tied round with a cord, to prevent his barking, and the man holds the other end of this cord in his hand. As soon as the dog smells the bear, he begins to show signs of uneasiness, and by dragging at the cord informs his master that the object of his pursuit is at no great distance. When the[Pg 84] Laplander by this means discovers on which side the bear is stationed, he advances in such a direction that the wind may blow from the bear to him, and not the contrary; for otherwise the animal would by the scent be aware of his approach, though not able to see an enemy at any considerable distance, being half blinded by the sunshine. When he has gradually advanced to within gunshot of the bear, he fires upon him; and this is the more easily accomplished in autumn, as the bear is then more fearless, and is continually prowling about for berries of different kinds, on which he feeds at that season of the year. Should the man chance to miss his aim, the furious beast will directly turn upon him in a rage, and the little Laplander is obliged to take to his heels with all possible speed, leaving his knapsack behind him on the spot. The bear coming up with this, seizes upon it, biting and tearing it into a thousand pieces. While he is thus venting his fury, and bestowing all his attention, upon the knapsack, the Lap[Pg 85]lander takes the opportunity of loading his gun, and firing a second time; when he is generally sure of hitting the mark, and the bear either falls upon the spot or runs away.

In the huts of this neighbourhood I observed an instrument which I had no where noticed before, consisting of an oblong board, placed transversely at the end of a pole. Its use is to stir the pot while boiling.

Directly opposite to Hyttan towards the west, and on the south of the mountain of Wallivari, is a vein of fine iron ore, but hardly worth working while the roads, by which it must be conveyed to Lulea, are in so bad a state.

This night I beheld a star, for the first time since I came within the arctic circle. Nevertheless the darkness was not considerable enough to prevent my reading or writing whatever I pleased.

One of the Laplanders had caught a[Pg 86] quantity of the fish called Sikloja (Salmo Albula) of a large size. He stuck about twenty of them on one spit, the back of each being placed towards the belly of the next, and they were thus roasted before the fire. These fish had previously been dried, though not at all salted.

The glue used by the Laplanders for joining the two portions of different woods of which their bows are made (see p. 66,) is prepared from the Common Perch (Perca fluviatilis) in the following manner. Some of the largest of this fish being flayed, the skins are first dried, and afterwards soaked in a small quantity of cold water, so that the scales can be rubbed off. Four or five of these skins being wrapped up together in a bladder, or in a piece of birch bark, so that no water can get at them, are set on the fire in a pot of water to boil, a stone being laid over the pot, to keep in the heat. The skins thus prepared make a very strong glue, insomuch that the articles joined with it will never separate again.[Pg 87] A bandage is tied round the bow while making, to hold the two parts the more firmly together.

When these people undertake a short journey only, they carry no bag for provisions, the latter being stored between their outer and inner jackets, which are always bound with a girdle, being wide, and formed of numerous folds, both above and below it.

The Purple Willow-herb, or Epilobium (angustifolium?) made the fields at this time very beautiful. The Golden-rod (Solidago Virgaurea) was likewise here in blossom, though not yet upon the alps, where it flowers later.

I have never yet seen any animal swim so light as the reindeer. During the dogdays the herds of reindeer, belonging to the inhabitants of the woody parts of Lapland, are very badly off for want of snow, with which those animals refresh themselves in hot weather upon the alps. Hence they constitute a more valuable and thriving pro[Pg 88]perty to the alpine Laplanders than to any others. In the winter time, when the favourite Lichen of the reindeer (L. rangiferinus) cannot be got at, their keepers fell trees laden with filamentous Lichens, to serve them for food; but it scarcely proves sufficient.

The rivulet near Kiomitis Trask has a very white appearance, as if milk had been mixed with it. This the inhabitants term kalkwatter, or lime-water, from the colour, not from any knowledge of its cause or origin. This rivulet they told me came from the alps. It empties itself into the great river near Kiomitis, and renders the water of that river white for the space of four or five miles. I noticed a similar phænomenon at Wirijaur.

I was amused with the mode in which these Laplanders take brandy. After they have laid hold of the mug, they dip their forefingers into the liquor, and rub a little on their foreheads, as well as on the middle of their bosoms. On inquiring the reason,[Pg 89] I was told their intention was that the brandy might not prove hurtful either to the head or breast.

Some people here were regaling themselves with fresh fish, of the kind lately mentioned (Salmo Albula), which having boiled into a mass like pap or flummery, they were eating out of their hands.

The dress of the Laplanders is, in one particular at least, very wisely contrived. Their thick collars effectually protect the throat and breast, which being furnished with numerous nerves and small muscles, and being the seat of the windpipe and of many principal veins and arteries, are very important and susceptible parts. The neck moreover, from its slender shape, is peculiarly exposed to cold. Hence the protection of clothing is found very necessary to the parts in question. For want of it our young women suffer much injury, which our youths avoid by running into the contrary extreme of tying their neckcloths[Pg 90] so tight as to make themselves as red in the face as if they were half strangled.

We Swedes are accustomed to have all our clothing made very tight. Not only the neckcloth, but the coat, waistcoat, breeches, stockings, sleeves, &c., must all stick close to the body, and the tighter they are the more fashionable. The Laplanders, on the contrary, wear only two, and those slight, bandages about them, which moreover are broad, and therefore less injurious than a narrow bandage in any part. Those to which I allude are the waistband and knees of their breeches, both made sufficiently loose and easy.