1, Lemna minor (Lesser Duckweed) nat. size.

2, Plant in flower.

3, Inflorescence containing two male flowers each of one stamen, and a female flower, the whole enclosed in a sheath.

4, Wolffia arrhiza.

(2, 3, 4 enlarged.)

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition,

Volume 8, Slice 8, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Edition, Volume 8, Slice 8

"Dubner" to "Dyeing"

Author: Various

Release Date: December 24, 2010 [EBook #34751]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ENCYC. BRITANNICA, VOL 8 SL 8 ***

Produced by Marius Masi, Don Kretz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber’s note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version. Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online. |

Articles in This Slice

DÜBNER, JOHANN FRIEDRICH (1802-1867), German classical scholar (naturalized a Frenchman), was born in Hör selgau, near Gotha, on the 20th of December 1802. After studying at the university of Göttingen he returned to Gotha, where from 1827-1832 he held a post (inspector coenobii) in connexion with the gymnasium. During this period he made his name known by editions of Justin and Persius (after Casaubon). In 1832 he was invited by the brothers Didot to Paris, to co-operate in a new edition of H. Etienne’s Greek Thesaurus. He also contributed largely to the Bibliotheca Graeca published by the same firm, a series of Greek classics with Latin translation, critical notes and valuable indexes. One of Dübner’s most important works was an edition of Caesar undertaken by command of Napoleon III., which obtained him the cross of the Legion of Honour. His editions are considered to be models of literary and philological criticism, and did much to raise the standard of classical scholarship in France. He violently attacked Burnouf’s method of teaching Greek, but without result. Dübner may have gone too far in his zeal for reform, and his opinions may have been too harshly expressed, but time has shown him to be right. The old text-books have been discarded, and a great improvement in classical teaching has taken place in recent years. Dübner died at Montreuil-sous-Bois, near Paris, on the 13th of December 1867.

See F. Godefroy, Notice sur J.F. Dübner (1867); Sainte-Beuve, Discours à la mémoire de Dübner (1868); article in Allgemeine deutsche Biographic.

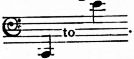

DUBOIS, FRANÇOIS CLÉMENT THÉODORE (1837- ), French musical composer, was born at Rosney (Marne) on the 24th of August 1837. He studied at the Conservatoire under Ambroise Thomas, and won the Grand Prix de Rome in 1861 with his cantata Atala. After the customary sojourn in Rome, Dubois returned to Paris and devoted himself to teaching. He was appointed “maitre de Chapelle” at the church of Ste Clotilde, where César Franck was organist, in 1863, and remained at this post for five years, during which time he composed a quantity of sacred music, notably Les Sept Paroles du Christ (1867), a work which has become well known in France. In 1868 he became “maitre de Chapelle” at the church of the Madeleine, and nine years later succeeded Camille Saint-Saëns there as organist. He became professor of harmony at the Conservatoire in 1871, and was appointed professor of composition in succession to Léo Delibes in 1891. At the death of Ambroise Thomas in 1896 he became director of the Conservatoire. Dubois is an extremely prolific composer and has written in a variety of forms. His sacred works include four masses, a requiem, Les Sept Paroles du Christ, a large number of motets and pieces for organ. For the theatre he has composed La Guzla de l’Émir, an opéra comique in one act, played at the Théâtre Lyrique de l’Athénée in 1873; Le Pain bis, an opéra comique in one act, given at the Opéra Comique in 1879; La Farandole, a ballet in three acts, produced at the Grand Opéra in 1883; Aben-Hamet, a four-act opera, heard at the Théâtre Italien in 1884; Xavière, a dramatic idyll in three acts, played at the Opéra Comique in 1895. His orchestral works include two concert overtures, the overture to Frithioff (1880), several suites, Marche héroïque de Jeanne d’Arc (1888), &c. He is also the author of Le Paradis perdu, an oratorio which gained for him the prize offered by the city of Paris in 1878; L’Enlèvement de Proserpine (1879), a scène lyrique; Délivrance (1887), a cantata; Hylas (1890), a scène lyrique for soli, chorus and orchestra; Notre Dame de la mer, a symphonic poem (1897); and a musical setting of a Latin ode on the baptism of Clovis (1899). In addition, he composed much for the piano and voice.

DUBOIS, GUILLAUME (1656-1723), French cardinal and statesman, was born at Brive, in Limousin, on the 6th of September 1656. He was, according to his enemies, the son of an apothecary, his father being in fact a doctor of medicine of respectable family, who kept a small drug store as part of the necessary outfit of a country practitioner. He was educated at the school of the Brothers of the Christian Doctrine at Brive, where he received the tonsure at the age of thirteen. In 1672, having finished his philosophy course, he was given a scholarship at the college of St Michel at Paris by Jean, marquis de Pompadour, lieutenant-general of the Limousin. The head of the college, the abbé Antoine Faure, who was from the same part of the country as himself, befriended the lad, and continued to do so for many years after he had finished his course, finding him pupils and ultimately obtaining for him the post of tutor to the young duke of Chartres, afterwards the regent duke of Orleans. Astute, ambitious and unrestrained by conscience, Dubois ingratiated himself with his pupil, and, while he gave him formal school lessons, at the same time pandered to his evil passions and encouraged him in their indulgence. He gained the favour of Louis XIV. by bringing about the marriage of his pupil with Mademoiselle de Blois, a natural but legitimated daughter of the king; and for this service he was rewarded with the gift of the abbey of St Just in Picardy. He was present with his pupil at the battle of Steinkirk, and “faced fire,” says Marshal Luxembourg, “like a grenadier.” Sent to join the French embassy in London, he made himself so active that he was recalled by the request of the ambassador, who feared his intrigues. This, however, tended to raise his credit with the king. When the duke of Orleans became regent (1715) Dubois, who had for some years acted as his secretary, was made councillor of state, and the chief power passed gradually into his hands.

His policy was steadily directed towards maintaining the peace of Utrecht, and this made him the main opponent of the schemes of Cardinal Alberoni for the aggrandizement of Spain. To counteract Alberoni’s intrigues, he suggested an alliance with England, and in the face of great difficulties succeeded in negotiating the Triple Alliance (1717). In 1719 he sent an army into Spain, and forced Philip V. to dismiss Alberoni. Otherwise his policy remained that of peace. Dubois’s success strengthened him against the bitter opposition of a large section of the court. Political honours did not satisfy him, however. The church offered the richest field for exploitation, and in spite of his dissolute life he impudently prayed the regent to give him the archbishopric of Cambray, the richest in France. His demand was supported by George I., and the regent yielded. 624 In one day all the usual orders were conferred on him, and even the great preacher Massillon consented to take part in the ceremonies. His next aim was the cardinalate, and, after long and most profitable negotiations on the part of Pope Clement XI., the red hat was given to him by Innocent XIII. (1721), whose election was largely due to the bribes of Dubois. It is estimated that this cardinalate cost France about eight million francs. In the following year he was named first minister of France (August). He was soon after received at the French Academy; and, to the disgrace of the French clergy, he was named president of their assembly.

When Louis XV. attained his majority in 1723 Dubois remained chief minister. He had accumulated an immense private fortune, possessing in addition to his see the revenues of seven abbeys. He was, however, a prey to the most terrible pains of body and agony of mind. His health was ruined by his debaucheries, and a surgical operation became necessary. This was almost immediately followed by his death, at Versailles, on the 10th of August 1723. His portrait was thus drawn by the duc de St Simon:—“He was a little, pitiful, wizened, herring-gutted man, in a flaxen wig, with a weasel’s face, brightened by some intellect. All the vices—perfidy, avarice, debauchery, ambition, flattery—fought within him for the mastery. He was so consummate a liar that, when taken in the fact, he could brazenly deny it. Even his wit and knowledge of the world were spoiled, and his affected gaiety was touched with sadness, by the odour of falsehood which escaped through every pore of his body.” This famous picture is certainly biassed. Dubois was unscrupulous, but so were his contemporaries, and whatever vices he had, he gave France peace after the disastrous wars of Louis XIV.

In 1789 appeared Vie privée du Cardinal Dubois, attributed to one of his secretaries, Mongez; and in 1815 his Mémoires secrets et correspondance inédite, edited by L. de Sevelinges. See also A. Cheruel, Saint-Simon et l’abbé Dubois; L. Wiesener, Le Régent, l’abbé Dubois et les Anglais (1891); and memoirs of the time.

DUBOIS, JEAN ANTOINE (1765-1848), French Catholic missionary in India, was ordained in the diocese of Viviers in 1792, and sailed for India in the same year under the direction of the Missions Étrangères. He was at first attached to the Pondicherry mission, and worked in the southern districts of the present Madras Presidency. On the fall of Seringapatam in 1799 he went to Mysore to reorganize the Christian community that had been shattered by Tipu Sultan. Among the benefits which he conferred upon his impoverished flock were the founding of agricultural colonies and the introduction of vaccination as a preventive of smallpox. But his great work was his record of Hindu Manners, Customs and Ceremonies. Immediately on his arrival in India he saw that the work of a Christian missionary should be based on a thorough acquaintance with the innermost life and character of the native population. Accordingly he abjured European society, adopted the native style of clothing, and made himself in habit and costume as much like a Hindu as he could. He gained an extraordinary welcome amongst people of all castes and conditions, and is still spoken of in many parts of South India with affection and esteem as “the prince’s son, the noblest of Europeans.” Although Dubois modestly disclaimed the rank of an author, his collections were not so much drawn from the Hindu sacred books as from his own careful and vivid observations, and it is this, united to a remarkable prescience, that makes his work so valuable. It is divided into three parts: (1) a general view of society in India, and especially of the caste system; (2) the four states of Brahminical life; (3) religion—feasts, temples, objects of worship. Not only does the abbé give a shrewd, clear-sighted, candid account of the manners and customs of the Hindus, but he provides a very sound estimate of the British position in India, and makes some eminently just observations on the difficulties of administering the Empire according to Western notions of civilization and progress with the limited resources that are available. Dubois’s French MS. was purchased for eight thousand rupees by Lord William Bentinck for the East India Company in 1807; in 1816 an English translation was published, and of this edition about 1864 a curtailed reprint was issued. The abbé, however, largely recast his work, and of this revised text (now in the India Office) an edition with notes was published in 1897 by H.K. Beauchamp. Dubois left India in January 1823, with a special pension conferred on him by the East India Company, and on reaching Paris was appointed director of the Missions Étrangères, of which he afterwards became superior (1836-1839). He translated into French the famous book of Hindu fables called Panchatantra, and also a work called The Exploits of the Guru Paramarta. Of more interest were his Letters on the State of Christianity in India, in which he asserted his opinion that under existing circumstances there was no human possibility of so overcoming the invincible barrier of Brahminical prejudice as to convert the Hindus as a nation to any sect of Christianity. He acknowledged that low castes and outcastes might be converted in large numbers, but of the higher castes he wrote: “Should the intercourse between individuals of both nations, by becoming more intimate and more friendly, produce a change in the religion and usages of the country, it will not be to turn Christians that they will forsake their own religion, but rather ... to become mere atheists.” He died in 1848.

DUBOIS, PAUL (1829-1905), French sculptor and painter, was born at Nogent-sur-Seine on the 18th of July 1829. He studied law to please his family, and art to please himself, and finally adopted the latter, and placed himself under Toussaint. After studying at the École des Beaux-Arts, Dubois went to Rome. His first contributions to the Paris Salon (1860) were busts of “The Countess de B.” and “A Child.” For his first statues, “St John the Baptist” and “Narcissus at the Bath” (1863), he was awarded a medal of the second class. The statue of “The Infant St John,” which had been modelled in Florence in 1860, was exhibited in Paris in bronze, and was acquired by the Luxemburg. “A Florentine Singer of the Fifteenth Century,” one of the most popular statuettes in Europe, was shown in 1865; “The Virgin and Child” appeared in the Paris Universal Exhibition in 1867; “The Birth of Eve” was produced in 1873, and was followed by striking busts of Henner, Dr Parrot, Paul Baudry, Pasteur, Gounod and Bonnat, remarkable alike for life, vivacity, likeness, refinement and subtle handling. The chief work of Paul Dubois was “The Tomb of General Lamoricière” in the cathedral of Nantes, a brilliant masterpiece conceived in the Renaissance spirit, with allegorical figures and groups representing Warlike Courage, Charity, Faith and Meditation, as well as bas-reliefs and enrichments; the two first-named works were separately exhibited in the Salon of 1877. The medallions represent Wisdom, Hope, Justice, Force, Rhetoric, Prudence and Religion. The statue of the “Constable Anne de Montmorency” was executed for Chantilly, and that of “Joan of Arc” (1889) for the town of Reims. The Italian influence which characterized the earlier work of Dubois disappeared as his own individuality became clearly asserted. As a painter he restricted himself mainly to portraiture. “My Children” (1876) being probably his most noteworthy achievement. His drawings and copies after the Old Masters are of peculiar excellence: they include “The Dead Christ” (after Sebastian del Piombo) and “Adam and Eve” (after Raphael). In 1873 Dubois was appointed keeper of the Luxemburg Museum. He succeeded Guillaume as director of the École des Beaux-Arts, 1878, and Perraud as member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Twice at the Salon he obtained the medal of honour (1865 and 1876), and once at the Universal Exhibition (1878). He also won numerous other distinctions, and was appointed grand cross of the Legion of Honour. He was made a member of several European orders, and in 1895 was elected an honorary foreign academician of the Royal Academy of London. He died at Paris in 1905.

DUBOIS, PIERRE (c. 1250-c. 1312), French publicist in the reign of Philip the Fair, was the author of a series of political pamphlets embodying original and daring views. He was known to Jean du Tillet in the 16th, and to Pierre Dupuy in the 17th century, but remained practically forgotten until the 625 middle of the 19th century, when his history was reconstructed from his works. He was a Norman by birth, probably a native of Coutances, where he exercised the functions of royal advocate of the bailliage and procurator of the university. He was educated at the university of Paris, where he heard St Thomas Aquinas and Siger of Brabant. He was, nevertheless, no adherent of the scholastic philosophy, and appears to have been conversant with the works of Roger Bacon. Although he never held any important political office, he must have been in the confidence of the court when, in 1300, he wrote his anonymous Summaria, brevis et compendiosa doctrina felicis expedicionis et abbreviationis guerrarum et litium regni Francorum, which is extant in a unique MS., but is analysed by N. de Wailly in the Bibliothèque de l’École des Chartes (2nd series, vol. iii.). In the contest between Philip the Fair and Boniface VIII. Dubois identified himself completely with the secularizing policy of Philip, and poured forth a series of anti-clerical pamphlets, which did not cease even with the death of Boniface. His Supplication du pueble de France au roy contre le pape Boniface le VIIIe, printed in 1614 in Acta inter Bonifacium VIII. et Philippum Pulchrum, dates from 1304, and is a heated indictment of the temporal power. He represented Coutances in the states-general of 1302, but in 1306 he was serving Edward I. as an advocate in Guienne, without apparently abandoning his Norman practice by which he had become a rich man. The most important of his works, his treatise De recuperatione terrae sanctae,1 was written in 1306, and dedicated in its extant form to Edward I., though it is certainly addressed to Philip. Dubois outlines the conditions necessary to a successful crusade—the establishment and enforcement of a state of peace among the Christian nations of the West by a council of the church; the reform of the monastic, and especially of the military, orders; the reduction of their revenues; the instruction of a number of young men and women in oriental languages and the natural sciences with a view to the government of Eastern peoples; and the establishment of Philip of Valois as emperor of the East. The king of France was in fact, when once the pope was deprived of the temporal power, to become the suzerain of the Western nations, and in a later and separate memoir Dubois proposed that he should cause himself to be made emperor by Clement V. His zeal for the crusade was probably subordinate to the desire to secure the wealth of the monastic orders for the royal treasury, and to transfer the ecclesiastical jurisdiction to the crown. His ideas on education, on the celibacy of the clergy, and his schemes for the codification of French law, were far in advance of his time. He was an early and violent “Gallican,” and the first of the great French lawyers who occupied themselves with high politics. In 1308 he attended the states-general at Tours. He is generally credited with Quaedam proposita papae a rege super facto Templariorum, a draft epistle supposed to be addressed to Clement by Philip. This was followed by other pamphlets in the same tone, in one of which he proposed that a kingdom founded on the property of the Templars in the East should be established on behalf of Philip the Tall.

See an article by E. Renan in Hist. litt. de la France, vol. xxvi. pp. 471-536; P. Dupuy Hist. de la condamnation ... des Templiers (Brussels, 1713), and Hist. du différend entre le pape Boniface VIII et Philippe le Bel (Paris 1655); and Notices et extraits de manuscrits, vol. xx.

1 Printed in Collections à servir à l’étude de l’histoire (1891).

DUBOIS, a borough of Clearfield county, Pennsylvania, U.S.A., 129 m. by rail N.E. of Pittsburg. Pop. (1890) 6149, (1900) 9375, of whom 1655 were foreign-born; (1910 census) 12,623. It is served by the Pennsylvania, the Buffalo, Rochester & Pittsburg, and the Buffalo & Susquehanna railways. The borough is built on a small plateau surrounded by hills, on the west slope of the Alleghany Mountains, nearly 1400 ft. above sea-level. Its chief importance is as a coal and lumber centre; among its manufacturing establishments are blast furnaces, iron works, machine shops, railway repair shops, tanneries, planing mills, flour mills, locomotive works and a glass factory. Dubois was first settled in 1872, was named in honour of its founder, John Dubois, and was incorporated in 1881.

DUBOIS-CRANCÉ, EDMOND LOUIS ALEXIS (1747-1814), French Revolutionist, born at Charleville, was at first a musketeer, then a lieutenant of the maréchaux, or guardsmen of the old régime. He embraced liberal ideas, and in 1789 was elected deputy to the states-general by the third estate of Vitry-le-François. At the Constituent Assembly, of which he was named secretary in November 1789, he busied himself mainly with military reforms. He wished to see the old military system, with its caste distinctions and its mercenaries, replaced by an organization of national guards in which all citizens should be admitted. In his report, on the 12th of December 1789, he gave utterance for the first time to the idea of conscription, which he opposed to the recruiting system of the old régime. His report was not, however, adopted. He succeeded in securing the Assembly’s vote that any slave who touched French soil should become free. After the Constituent, Dubois-Crancé was named maréchal de camp, but he refused to be placed under the orders of Lafayette and preferred to serve as a simple grenadier. Elected to the Convention by the department of the Ardennes, he sat among the Montagnards, but without following any one leader, either Danton or Robespierre. In the trial of Louis XVI. he voted for death without delay or appeal. On the 21st of February 1793 he was named president of the Convention. Although he was a member of the two committees of general defence which preceded that of public safety, he did not belong to the latter at its creation. But he composed a remarkable report on the army, recommending two measures which contributed largely to its success, the rapid advancement of the lower officers, which opened the way for the most famous generals of the Revolution, and the fusion of the volunteers with the veteran troops. In August 1793 Dubois-Crancé was designated “representative on mission” to the army of the Alps, to direct the siege of Lyons, which had revolted against the republic. Accused of lack of energy, he was replaced by G. Couthon. On his return he easily justified himself, but was excluded from the Jacobin club at the instance of Robespierre, before whom he refused to bend. Consequently he was naturally drawn to participate in the revolution of the 9th of Thermidor of the year II., directed against Robespierre. But he would not join the Royalist reaction which followed, and was one of the committee of five which had to oppose the Royalist insurrection of Vendémiaire (see French Revolution). It was also during this period that Dubois-Crancé was named a member of the committee of public safety, then much reduced in importance. After the Convention, under the Directory, Dubois-Crancé was a member of the Council of the Five Hundred, and was appointed inspector-general of infantry; then, in 1799, minister of war. Opposed to the coup d’état of the 18th of Brumaire, he lived in retirement during the Consulate and the Empire. He died at Rethel on the 29th of June 1814. His portrait stands in the foreground in J.L. David’s celebrated sketch of the “Oath of the Tennis Court.”

Among the numerous writings of Dubois-Crancé may be noticed his Observations sur la constitution militaire, ou bases du travail proposé au comité militaire. See H.F.T. Jung, Dubois de Crancé. L’armée et la Révolution, 1789-1794 (2 vols., Paris, 1884).

DU BOIS-REYMOND, EMIL (1818-1896), German physiologist, was born in Berlin on the 7th of November 1818. The Prussian capital was the place both of his birth and of his life’s work, and he will always be counted among Germany’s great scientific men; yet he was not of German blood. His father belonged to Neuchâtel, his mother was of Huguenot descent, and he spoke of himself as “being of pure Celtic blood.” Educated first at the French college in Berlin, then at Neuchâtel, whither his father had returned, he entered in 1836 the university of Berlin. He seems to have been uncertain at first as to the bent of his studies, for he sat at the feet of the great ecclesiastical historian August Neander, and dallied with geology; but eventually he threw himself into the study of medicine, with such zeal and success as to attract the notice of the great teacher of anatomy and physiology, who was then making Berlin famous as a school for the sciences ancillary to medicine. Johannes Müller may be regarded as the central figure in the history of modern physiology. 626 the physiology of the 19th century. Müller’s earlier studies had been distinctly physiological; but his inclination, no less than his position as professor of anatomy as well as of physiology in the university of Berlin, led him later on into wide studies of comparative anatomy, and these, aided by the natural bent of his mind towards problems of general philosophy, gave his views of physiology a breadth and a depth which profoundly influenced the progress of that science in his day. He had, about the time when the young Du Bois-Reymond came to his lectures, published his great Elements of Physiology, the dominant note of which may be said to be this:—“Though there appears to be something in the phenomena of living beings which cannot be explained by ordinary mechanical, physical or chemical laws, much may be so explained, and we may without fear push these explanations as far as we can, so long as we keep to the solid ground of observation and experiment.” Müller recognized in the Neuchâtel lad a mind fitted to carry on physical researches into the phenomena of living things in a legitimate way. He made him in 1840 his assistant in physiology, and as a starting-point for an inquiry put into his hands the essay which the Italian, Carlo Matteucci, had just published on the electric phenomena of animals. This determined the work of Du Bois-Reymond’s life. He chose as the subject of his graduation thesis “Electric Fishes,” and so commenced a long series of investigations on animal electricity, by which he enriched science and made for himself a name. The results of these inquiries were made known partly in papers communicated to scientific journals, but also and chiefly in his work Researches on Animal Electricity, the first part of which appeared in 1848, the last in 1884.

This great work may be regarded under two aspects. On the one hand, it is a record of the exact determination and approximative analysis of the electric phenomena presented by living beings. Viewed from this standpoint, it represents a remarkable advance of our knowledge. Du Bois-Reymond, beginning with the imperfect observations of Matteucci, built up, it may be said, this branch of science. He did so by inventing or improving methods, by devising new instruments of observation or by adapting old ones. The debt which science owes to him on this score is a large one indeed. On the other hand, the volumes in question contain an exposition of a theory. In them Du Bois-Reymond put forward a general conception by the help of which he strove to explain the phenomena which he had observed. He developed the view that a living tissue, such as muscle, might be regarded as composed of a number of electric molecules, of molecules having certain electric properties, and that the electric behaviour of the muscle as a whole in varying circumstances was the outcome of the behaviour of these native electric molecules. It may perhaps be said that this theory has not stood the test of time so well as have Du Bois-Reymond’s other more simple deductions from observed facts. It was early attacked by Ludimar Hermann, who maintained that a living untouched tissue, such as a muscle, is not the subject of electric currents so long as it is at rest, is isoelectric in substance, and therefore need not be supposed to be made up of electric molecules, all the electric phenomena which it manifests being due to internal molecular changes associated with activity or injury. Although most subsequent observers have ranged themselves on Hermann’s side, it must nevertheless be admitted that Du Bois-Reymond’s theory was of great value if only as a working hypothesis, and that as such it greatly helped in the advance of science.

Du Bois-Reymond’s work lay chiefly in the direction of animal electricity, yet he carried his inquiries—such as could be studied by physical methods—into other parts of physiology, more especially into the phenomena of diffusion, though he published little or nothing concerning the results at which he arrived. For many years, too, he exerted a great influence as a teacher. In 1858, upon the death of Johannes Müller, the chair of anatomy and physiology, which that great man had held, was divided into a chair of human and comparative anatomy, which was given to K.B. Reichert (1811-1883), and a chair of physiology, which naturally fell to Du Bois-Reymond. This he held to his death, carrying out his researches for many years under unfavourable conditions of inadequate accommodation. In 1877, through his influence, the government provided the university with a proper physiological laboratory. In 1851 he was admitted into the Academy of Sciences of Berlin, and in 1867 became its perpetual secretary. For many years he and his friend H. von Helmholtz, who like him had been a pupil of Johannes Müller, were prominent men in the German capital. Acceptable at court, they both used their position and their influence for the advancement of science. Both, from time to time as opportunity offered, stepped out of the narrow limits of the professorial chair and gave the world their thoughts concerning things on which they could not well dwell in the lecture room. Du Bois-Reymond, as has been said, had in his earlier years wandered into fields other than those of physiology and medicine, and in his later years he went back to some of these. His occasional discourses, dealing with general topics and various problems of philosophy, show that to the end he possessed the historic spirit which had led him as a lad to listen to Neander; they are marked not only by a charm of style, but by a breadth of view such as might be expected from Johannes Müller’s pupil and friend. He died in the city of his birth and adoption on the 26th of November 1896.

DUBOS, JEAN-BAPTISTE (1670-1742), French author, was born at Beauvais in December 1670. After studying for the church, he renounced theology for the study of public law and politics. He was employed by M. de Torcy, minister of foreign affairs, and by the regent and Cardinal Dubois in several secret missions, in which he acquitted himself with great success. He was rewarded with a pension and several benefices. Having obtained these, he retired from political life, and devoted himself to history and literature. He gained such distinction as an author that in 1720 he was elected a member of the French Academy, of which, in 1723, he was appointed perpetual secretary in the room of M. Dacier. He died at Paris on the 23rd of March 1742, repeating as he expired the well-known remark of an ancient, “Death is a law, not a punishment.” His first work was L’Histoire des quatre Gordiens prouvée et illustrée par des médailles (Paris, 1695, 12mo), which, in spite of its ingenuity, did not succeed in altering the common opinion, which only admits three emperors of this name. About the commencement of the war of 1701, being charged with different negotiations both in Holland and in England, with the design to engage these powers if possible to adopt a pacific line of policy, he, in order to promote the objects of his mission, published a work entitled Les Intérêts de l’Angleterre mal entendus dans la guerre présente (Amsterdam, 1703, 12mo). But as this work contained indiscreet disclosures, of which the enemy took advantage, and predictions which were not fulfilled, a wag took occasion to remark that the title ought to be read thus: Les Intérêts de l’Angleterre mal entendus par l’abbé Dubos. It is remarkable as containing a distinct prophecy of the revolt of the American colonies from Great Britain. His next work was L’Histoire de la Ligue de Cambray (Paris, 1709, 1728 and 1785, 2 vols. 12mo), a full, clear and interesting history, which obtained the commendation of Voltaire. In 1734 he published his Histoire critique de l’établissement de la monarchie française dans les Gaules (3 vols. 4to)—a work the object of which was to prove that the Franks had entered Gaul, not as conquerors, but at the request of the nation, which, according to him, had called them in to govern it. But this system, though unfolded with a degree of skill and ability which at first procured it many zealous partisans, was victoriously refuted by Montesquieu at the end of the thirtieth book of the Esprit des lois. His Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et sur la peinture, published for the first time in 1719 (2 vols. 12mo), but often reprinted in three volumes, constitute one of the works in which the theory of the arts is explained with the utmost sagacity and discrimination. Like his history of the League of Cambray, it was highly praised by Voltaire. The work was rendered more remarkable by the fact that its author had no practical acquaintance with any one of the arts whose principles he discussed. Besides the works above enumerated, a manifesto of Maximilian, elector of Bavaria, against the emperor Leopold, relative to the succession in Spain, has been 627 attributed to Dubos, chiefly, it appears, from the excellence of the style.

DUBUQUE, a city and the county-seat of Dubuque county, Iowa, U.S.A., on the Mississippi river, opposite the boundary line between Wisconsin and Illinois. Pop. (1890) 30,311; (1900) 36,297; (1905, state census) 41,941 (including 6835 foreign-born, the majority of whom were German and Irish); (1910 U.S. census) 38,494. Dubuque is served by the Illinois Central, the Chicago, Milwaukee & Saint Paul (which has repair shops here), the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy, and the Chicago Great Western railways; it also has a considerable river traffic. The river is spanned here by a railway bridge and two wagon bridges. The business portion of the city lies on the low lands bordering the river; many of the residences are built on the slopes and summits of bluffs commanding extensive and picturesque views. Among the principal buildings are the Carnegie-Stout free public library (which in 1908 had 23,600 volumes, exclusive of the valuable Senator Allison collection of public documents), the public high school, and the house of the Dubuque Club. Dubuque is a Roman Catholic archiepiscopal see, and is the seat of St Joseph’s College (1873), a small Roman Catholic institution; of Wartburg Seminary (1854), a small Evangelical Lutheran theological school; of the German Presbyterian Theological School of the North-west (1852); of St Joseph’s Ladies’ Academy; and of Bayless Business College. Fifteen miles from Dubuque is a monastery of Trappist monks. Among the city’s charitable institutions are the Finley and the Mercy hospitals, a home for the friendless, a rescue home, a House of the Good Shepherd, and an insane asylum. In 1900 Dubuque ranked fourth and in 1905 fifth among the cities of the state as a manufacturing centre, the chief products being those of the planing mills and machine shops, and furniture, sashes and doors, liquors, carriages, wagons, coffins, clothing, boots and shoes, river steam boats, barges, torpedo boats, &c., and the value of the factory product being $9,279,414 in 1905 and $9,651,247 in 1900. The city lies in a region of lead and zinc mines, quantities of zinc ore in the form of black-jack being taken from the latter. Dubuque is important as a distributing centre for lumber, hardware, groceries and dry-goods.

As early as 1788 Julien Dubuque (1765-1810), attracted by the lead deposits in the vicinity, which were then being crudely worked by the Sauk and Fox Indians, settled here and carried on the mining industry until his death. In June 1829 miners from Galena, Illinois, attempted to make a settlement here in direct violation of Indian treaties, but were driven away by United States troops under orders from Colonel Zachary Taylor. Immediately after the Black Hawk War, white settlers began coming to the mines. Dubuque was laid out under an act of Congress approved on the 2nd of July 1836, and was incorporated in 1841.

DU CAMP, MAXIME (1822-1894), French writer, the son of a successful surgeon, was born in Paris on the 8th of February 1822. He had a strong taste for travel, which his father’s means enabled him to indulge as soon as his college days were over. Between 1844 and 1845, and again, in company with Gustave Flaubert, between 1849 and 1851, he travelled in Europe and the East, and made excellent use of his experiences in books published after his return. In 1851 he was one of the founders of the Revue de Paris (suppressed in 1858), and was a frequent contributor to the Revue des deux mondes. In 1853 he was made an officer of the Legion of Honour. He served as a volunteer with Garibaldi in 1860, and gave an account of his experiences in his Expédition des deux Siciles (1861). In 1870 he was nominated for the senate, but his election was frustrated by the downfall of the Empire. He was elected a member of the French Academy in 1880, mainly, it is said, on account of his history of the Commune, published under the title of Les Convulsions de Paris (1878-1880). His writings include among others the Chants modernes (1855), Convictions (1858); numerous works on travel, Souvenirs et paysages d’orient (1848), Égypte, Nubie, Palestine, Syrie (1852); works of art criticism, Les Salons de 1857, 1859, 1861; novels, L’Homme au bracelet d’or (1862), Une Histoire d’amour (1889); literary studies, Théophile Gautier (1890). Du Camp was the author of a valuable book on the daily life of Paris, Paris, ses organes, ses fonctions, sa vie dans la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle (1869-1875). He published several works on social questions, one of which, the Mœurs de mon temps, was to be kept sealed in the Bibliothèque Nationale until 1910. His Souvenirs littéraires (2 vols., 1882-1883) contain much information about contemporary writers, especially Gustave Flaubert, of whom Du Camp was an early and intimate friend. He died on the 9th of February 1894. Du Camp was one of the earliest amateur photographers, and his books of travel were among the first to be illustrated by means of what was then a new art.

DU CANGE, CHARLES DU FRESNE, Sieur (1610-1688), one of the lay members of the great 17th century group of French critics and scholars who laid the foundations of modern historical criticism, was born at Amiens on the 18th of December 1610. At an early age his father sent him to the Jesuits’ college at Amiens, where he greatly distinguished himself. Having completed the usual course at this seminary, he applied himself to the study of law at Orleans, and afterwards went to Paris, where in 1631 he was received as an advocate before the parliament. Meeting with very slight success in his profession, he returned to his native city, and in July 1638 married Catherine Dubois, daughter of a royal official, the treasurer in Amiens; and in 1647 he purchased the office of treasurer from his father-in-law, but its duties did not interfere with the literary and historical work to which he had devoted himself since returning to Amiens. Forced to leave his native city in 1668 in consequence of a plague, he settled in Paris, where he resided until his death on the 23rd of October 1688. In the archives of Paris Du Cange was able to consult charters, diplomas, manuscripts and a multitude of printed documents, which were not to be met with elsewhere. His industry was exemplary and unremitting, and the number of his literary works would be incredible, if the originals, all in his own handwriting, were not still extant. He was distinguished above nearly all the writers of his time by his linguistic acquirements, his accurate and varied knowledge, and his critical sagacity. Of his numerous works the most important are the Glossarium ad scriptores mediae et infimae latinitatis (Paris, 1678), and the Glossarium ad scriptores mediae et infimae graecitatis (Lyons, 1688), which are indispensable aids to the student of the history and literature of the middle ages. To the three original volumes of the Latin Glossarium, three supplementary volumes were added by the Benedictines of St Maur (Paris, 1733-1736), and a further addition of four volumes (Paris, 1766), by a Benedictine, Pierre Carpentier (1697-1767). There were other editions, and an abridgment with some corrections was brought out by J.C. Adelung (Halle, 1772-1784). The edition in seven volumes edited by G.A.L. Henschel (Paris, 1840-1850) includes these supplements and also further additions by the editor, and this has been improved and published in ten volumes by Léopold Favre (Niort, 1883-1887). An edition of the Greek Glossarium was published at Breslau in 1889.

Du Cange took considerable interest in the history of the later empire, and wrote Historia Byzantina duplici commentario illustrato (Paris, 1680), and an introduction to his edition and translation into modern French of Geoffrey de Villehardouin’s Histoire de l’empire de Constantinople sous les empereurs français (Paris, 1657). He also brought out editions of the Byzantine historians, John Cinnamus and John Zonaras, as Joannis Cinnami historiarum de rebus gestis a Joanne et Manuele Comnenis (Paris, 1670) and Joannis Zonarae Annales ab exordio mundi ad mortem Alexii Comneni (Paris, 1686). He edited Jean de Joinville’s Histoire de St Louis, roi de France (Paris, 1668), and his other works which may be mentioned are Traité historique du chef de St Jean Baptiste (Paris, 1666); Lettre du Sieur N., conseiller du roi (Paris, 1682); Cyrilli, Philoxeni, aliorumque veterum glossaria, and Mémoire sur le projet d’un nouveau recueil des historiens de France, avec le plan général de ce recueil, which has been inserted by Jacques Lelong in his Bibliothèque historique de la 628 France (Paris, 1768-1778). His last work, Chronicon Paschale a mundo condito ad Heraclii imperatoris annum vigesimum (Paris, 1689), was passing through the press when Du Cange died, and consequently it was edited by Étienne Baluze, and published with an éloge of the author prefixed.

His autograph manuscripts and his large and valuable library passed to his eldest son, Philippe du Fresne, who died unmarried in 1692. They then came to his second son, François du Fresne, who sold the collection, the greater part of the manuscripts being purchased by the abbé du Champs. The abbé handed them over to a bookseller named Mariette, who resold part of them to Baron Hohendorf. The remaining part was acquired by a member of the family of Hozier, the French genealogists. The French government, however, aware of the importance of all the writings of Du Cange, succeeded, after much trouble, in collecting the greater portion of the manuscripts, which were preserved in the imperial library at Paris. Some of these were subsequently published, and the manuscripts are now found in various libraries. The works of Du Cange published after his death are: an edition of the Byzantine historian, Nicephorus Gregoras (Paris, 1702); De imperatorum Constantinopolitanorum seu inferioris aevi vel imperii uti vocant numismatibus dissertatio (Rome, 1755); Histoire de l’état de la ville d’Amiens et de ses comtes (Amiens, 1840); and a valuable work Des principautés d’outre-mer, published by E.G. Rey as Les Familles d’outre-mer (Paris, 1869).

See H. Hardouin, Essai sur la vie et sur les ouvrages de Ducange (Amiens, 1849); and L.J. Feugère, in the Journal de l’instruction publique (Paris, 1852).

DUCANGE, VICTOR HENRI JOSEPH BRAHAIN (1783-1833), French novelist and dramatist, was born on the 24th of November 1783 at the Hague, where his father was secretary to the French embassy. Dismissed from the civil service at the Restoration, Victor Ducange became one of the favourite authors of the liberal party, and owed some part of his popularity to the fact that he was fined and imprisoned more than once for his outspokenness. He was six months in prison for an article in his journal Le Diable rose, ou le petit courrier de Lucifer (1822); for Valentine (1821), in which the royalist excesses in the south of France were pilloried, he was again imprisoned; and after the publication of Hélène ou l’amour et la guerre (1823), he took refuge for some time in Belgium. Ducange wrote numerous plays and melodramas, among which the most successful were Marco Loricot, ou le petit Chouan de 1830 (1836), and Trente ans, ou la vie d’un joueur (1827), in which Fréderick Lemaître found one of his best parts. Many of his books were prohibited, ostensibly for their coarseness, but perhaps rather for their political tendencies. He died in Paris on the 15th of October 1833.

DUCAS, Dukas or Doukas, the name of a Byzantine family which supplied several rulers to the Eastern Empire. The family first came into prominence during the 9th century, but was ruined when Constantine Ducas, a son of the general Andronicus Ducas, lost his life in his effort to obtain the imperial crown in 913. Towards the end of the 10th century there appeared another family of Ducas, which was perhaps connected with the earlier family through the female line and was destined to attain to greater fortune. A member of this family became emperor as Constantine X. in 1059, and Constantine’s son Michael VII. ruled, nominally in conjunction with his younger brothers, Andronicus and Constantine, from 1071 to 1078. Michael left a son, Constantine, and, says Gibbon, “a daughter of the house of Ducas illustrated the blood, and confirmed the succession, of the Comnenian dynasty.” The family was also allied by marriage with other great Byzantine houses, and after losing the imperial dignity its members continued to take an active part in public affairs. In 1204 Alexius Ducas, called Mourzoufle, deposed the emperor Isaac Angelus and his son Alexius, and vainly tried to defend Constantinople against the attacks of the Latin crusaders. Nearly a century and a half later one Michael Ducas took a leading part in the civil war between the emperors John V. Palaeologus and John VI. Cantacuzenus, and Michael’s grandson was the historian Ducas (see below). Many of the petty sovereigns who arose after the destruction of the Eastern Empire sought to gain prestige by adding the famous name of Ducas to their own.

DUCAS (15th cent.), Byzantine historian, flourished under Constantine XIII. (XI.) Dragases, the last emperor of the East, about 1450. The dates of his birth and death are unknown. He was the grandson of Michael Ducas (see above). After the fall of Constantinople, he was employed in various diplomatic missions by Dorino and Domenico Gateluzzi, princes of Lesbos, where he had taken refuge. He was successful in securing a semi-independence for Lesbos until 1462, when it was taken and annexed to Turkey by Sultan Mahommed II. It is known that Ducas survived this event, but there is no record of his subsequent life. He was the author of a history of the period 1341-1462; his work thus continues that of Gregoras and Cantacuzene, and supplements Phrantzes and Chalcondyles. There is a preliminary chapter of chronology from Adam to John Palaeologus I. Although barbarous in style, the history of Ducas is both judicious and trustworthy, and it is the most valuable source for the closing years of the Greek empire. The account of the capture of Constantinople is of special importance. Ducas was a strong supporter of the union of the Greek and Latin churches, and is very bitter against those who rejected even the idea of appealing to the West for assistance against the Turks.

The history, preserved (without a title) in a single Paris MS., was first edited by I. Bullialdus (Bulliaud) (Paris, 1649); later editions are in the Bonn Corpus scriptorum Hist. Byz., by I. Bekker (1834) and Migne, Patrologia Graeca, clvii. The Bonn edition contains a 15th century Italian translation by an unknown author, found by Leopold Ranke in one of the libraries of Venice, and sent by him to Bekker.

DUCASSE, PIERRE EMMANUEL ALBERT, Baron (1813-1893), French historian, was born at Bourges on the 16th of November 1813. In 1849 he became aide-de-camp to Prince Jerome Bonaparte, ex-king of Westphalia, then governor of the Invalides, on whose commission he wrote Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire de la campagne de 1812 en Russie (1852). Subsequently he published Mémoires du roi Joseph (1853-1855), and, as a sequel, Histoire des négociations diplomatiques relatives aux traités de Morfontaine, de Lunéville et d’Amiens, together with the unpublished correspondence of the emperor Napoleon I. with Cardinal Fesch (1855-1856). From papers in the possession of the imperial family he compiled Mémoires du prince Eugène (1858-1860) and Réfutation des mémoires du duc de Raguse (1857), part of which was inserted by authority at the end of volume ix. of the Mémoires. He was attaché to Jerome’s son, Prince Napoleon, during the Crimean War, and wrote a Précis historique des opérations militaires en Orient, de mars 1854 à octobre 1855 (1857), which was completed many years later by a volume entitled La Crimée et Sébastopol de 1853 à 1856, documents intimes et inédits, followed by the complete list of the French officers killed or wounded in that war (1892). He was also employed by Prince Napoleon on the Correspondance of Napoleon I., and afterwards published certain letters, purposely omitted there, in the Revue historique. These documents, subsequently collected in Les Rois frères de Napoléon (1883), as well as the Journal de la reine Catherine de Westphalie (1893), were edited with little care and are not entirely trustworthy, but their publication threw much light on Napoleon I. and his entourage. His Souvenirs d’un officier du 2e Zouaves, and Les Dessous du coup d’état (1891), contain many piquant anecdotes, but at times degenerate into mere tittle-tattle. Ducasse was the author of some slight novels, and from the practice of this form of literature he acquired that levity which appears even in his most serious historical publications.

DUCAT, the name of a coin, generally of gold, and of varying value, formerly in use in many European countries. It was first struck by Roger II. of Sicily as duke of Apulia, and bore an inscription “Sit tibi, Christe, datus, quem tu regis, iste ducatus” (Lord, thou rulest this duchy, to thee be it dedicated); hence, it is said, the name. Between 1280 and 1284 Venice also struck 629 a gold coin, known first as the ducat, afterwards as the zecchino or sequin, the ducat becoming merely a money of account. The ducat was also current in Holland, Austria, the Netherlands, Spain and Denmark (see Numismatics). A gold coin termed a ducat was current in Hanover during the reigns of George I. and George III. A pattern gold coin was also struck by the English mint in 1887 for a proposed decimal coinage. On the reverse was the inscription “one ducat” within an oak wreath; above “one hundred pence,” and below the date between two small roses. There is a gold coin termed a ducat in the Austria-Hungary currency, of the value of nine shillings and fourpence.

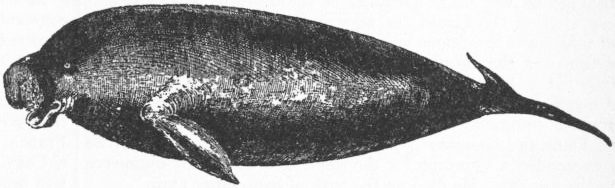

DU CHAILLU, PAUL BELLONI (1835-1903), traveller and anthropologist, was born either at Paris or at New Orleans (accounts conflict) on the 31st of July 1835. In his youth he accompanied his father, an African trader in the employment of a Parisian firm, to the west coast of Africa. Here, at a station on the Gabun, the boy received some education from missionaries, and acquired an interest in and knowledge of the country, its natural history, and its natives, which guided him to his subsequent career. In 1852 he exhibited this knowledge in the New York press, and was sent in 1855 by the Academy of Natural Sciences at Philadelphia on an African expedition. From 1855 to 1859 he regularly explored the regions of West Africa in the neighbourhood of the equator, gaining considerable knowledge of the delta of the Ogowé river and the estuary of the Gabun. During his travels he saw numbers of the great anthropoid apes called the gorilla (possibly the great ape described by Carthaginian navigators), then known to scientists only by a few skeletons. A subsequent expedition, from 1863 to 1865, enabled him to confirm the accounts given by the ancients of a pygmy people inhabiting the African forests. Narratives of both expeditions were published, in 1861 and 1867 respectively, under the titles Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa, with Accounts of the Manners and Customs of the People, and of the Chace of the Gorilla, Crocodile, and other Animals; and A Journey to Ashango-land, and further penetration into Equatorial Africa. The first work excited much controversy on the score of its veracity, but subsequent investigation proved the correctness of du Chaillu’s statements as to the facts of natural history; though possibly some of the adventures he described as happening to himself were reproductions of the hunting stories of natives (see Proc. Zool. Soc. vol. i., 1905, p. 66). The map accompanying Ashango-land was of unique value, but the explorer’s photographs and collections were lost when he was forced to flee from the hostility of the natives. After some years’ residence in America, during which he wrote several books for the young founded upon his African adventures, du Chaillu turned his attention to northern Europe, and published in 1881 The Land of the Midnight Sun, in 1889 The Viking Age, and in 1900 The Land of the Long Night. He died at St Petersburg on the 29th of April 1903.

DUCHENNE, GUILLAUME BENJAMIN AMAND (1806-1875), French physician, was born on the 17th of September 1806 at Boulogne, the son of a sea-captain. He was educated at Douai, and then studied medicine in Paris until the year 1831, when he returned to his native town to practise his profession. Two years later he first tried the effect of electro-puncture of the muscles on a patient under his care, and from this time on devoted himself more and more to the medical applications of electricity, thereby laying the foundation of the modern science of electro-therapeutics. In 1842 he removed to Paris for the sake of its wider clinical opportunities, and there he worked until his death over thirty years later. His greatest work, L’Électrisation localisée (1855), passed through three editions during his lifetime, though by many his Physiologie des mouvements (1867) is considered his masterpiece. He published over fifty volumes containing his researches on muscular and nervous diseases, and on the applications of electricity both for diagnostic purposes and for treatment. His name is especially connected with the first description of locomotor ataxy, progressive muscular atrophy, pseudo-hypertrophic paralysis, glosso-labio laryngeal paralysis and other nervous troubles. He died in Paris on the 17th of September 1875.

For a detailed life see Archives générales de médicine (December 1875), and for a complete list of his works the 3rd edition of L’Électrisation localisée (1872).

DU CHESNE [Latinized Duchenius, Querneus, or Quercetanus], ANDRÉ (1584-1640), French geographer and historian, generally styled the father of French history, was born at Ile-Bouchard, in the province of Touraine, in May 1584. He was educated at Loudun and afterwards at Paris. From his earliest years he devoted himself to historical and geographical research, and his first work, Egregiarum seu selectarum lectionum et antiquitatum liber, published in his eighteenth year, displayed great erudition. He enjoyed the patronage of Cardinal Richelieu, a native of the same district with himself, through whose influence he was appointed historiographer and geographer to the king. He died in 1640, in consequence of having been run over by a carriage when on his way from Paris to his country house at Verrière. Du Chesne’s works were very numerous and varied, and in addition to what he published, he left behind him more than 100 folio volumes of manuscript extracts now preserved in the Bibliothèque Nationale (L. Delisle, Le Cabinet des manuscrits de la bibliothèque impériale, t. L, 333-334). Several of his larger works were continued by his only son François du Chesne (1616-1693), who succeeded him in the office of historiographer to the king. The principal works of André du Chesne are—Les Antiquités et recherches de la grandeur et majesté des rois de France (Paris, 1609), Les Antiquités et recherches des villes, châteaux, &c., de toute la France (Paris, 1609), Histoire d’Angleterre, d’Écosse, et d’Irelande (Paris, 1614), Histoire des Papes jusqu’à Paul V (Paris, 1619), Histoire des rois, ducs, et comtes de Bourgogne (1619-1628, 2 vols. fol.), Historiae Normanorum scriptores antiqui (1619, fol., now the only source for some of the texts), and his Historiae Francorum scriptores (5 vols. fol., 1636-1649). This last was intended to comprise 24 volumes, and to contain all the narrative sources for French history in the middle ages; only two volumes were published by the author, his son François published three more, and the work remained unfinished. Besides these du Chesne published a great number of genealogical histories of illustrious families, of which the best is that of the house of Montmorency. His Histoire des cardinaux français (2 vols. fol. 1660-1666) and Histoire des chanceliers et gardes des sceaux de France (1630) were published by his son François. André also published a translation of the Satires of Juvenal, and editions of the works of Alcuin, Abelard, Alain Chartier and Étienne Pasquier.

DUCHESNE, LOUIS MARIE OLIVIER (1843- ), French scholar and ecclesiastic, was born at Saint Servan in Brittany on the 13th of September 1843. Two scientific missions—to Mount Athos in 1874 and to Asia Minor in 1876—appeared at first to incline him towards the study of the ancient history of the Christian churches of the East. Afterwards, however, it was the Western church which absorbed almost his whole attention. In 1877 he received the degree of docteur ès lettres with two remarkable theses, a dissertation De Macario magnete, and an Étude sur le Liber pontificalis, in which he explained with unerring critical acumen the origin of that celebrated chronicle, determined the different editions and their interrelation, and stated precisely the value of his evidence. Immediately afterwards he was appointed professor at the Catholic Institute in Paris, and for eight years presented the example and model, then rare in France, of a priest teaching church history according to the rules of scientific criticism. His course, bold even to the point of rashness in the eyes of the traditionalist exegetists, was at length suspended. In November 1885 he was appointed lecturer at the École Pratique des Hautes Études. In 1886 he published volume i. of his learned edition of the Liber pontificalis (completed in 1892 by volume ii.), in which he resumed and completed the results he had attained in his French thesis. In 1888 he was elected member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, and was afterwards appointed director of the French school of archaeology at Rome. Much light is thrown upon the Christian origins, especially those of France, by his Origines du culte chrétien, étude sur la liturgie latine avant Charlemagne 630 (1889; Eng. trans. by M.L. McClure, Christian Worship: its Origin and Evolution, London, 1902, 2nd ed. 1904); Mémoire sur l’origine des diocèses épiscopaux dans l’ancienne Gaule (1890), the preliminary sketch of a more detailed work, Fastes épiscopaux dans l’ancienne Gaule (vol. i. Les provinces du sud-est, 1894, and vol. ii. L’Aquitaine et les Lyonnaises, 1899); and Catalogues épiscopaux de la province de Tours (1898). When a proposal was set on foot to bring about a reconciliation between the Roman Church and the Christian Churches of the East, the Abbé Duchesne endeavoured to show that the union of those churches was possible under the Roman supremacy, because unity did not necessarily entail uniformity. His Autonomies ecclésiastiques; églises séparées (1897), in which he speaks of the origin of the Anglican Church, but treats especially of the origin of the Greek Churches of the East, was received with scant favour in certain narrow circles of the pontifical court. In 1906 he began to publish, under the title of Histoire ancienne de l’église, a course of lectures which he had already delivered upon the early ages of the Church, and of which a few manuscript copies were circulated. The second volume appeared in 1908. In these lectures Duchesne touches cleverly upon the most delicate problems, and, without any elaborate display of erudition, presents conclusions of which account must be taken. His incisive style, his fearless and often ruthless criticism, and his wide and penetrating erudition, make him a redoubtable adversary in the field of polemic. The Bulletin critique, founded by him, for which he wrote numerous articles, has contributed powerfully to spread the principles of the historical method among the French clergy.

DUCIS, JEAN FRANÇOIS (1733-1816), French dramatist and adapter of Shakespeare, was born at Versailles on the 22nd of August 1733. His father, originally from Savoy, was a linen-draper at Versailles; and all through life he retained the simple tastes and straightforward independence fostered by his bourgeois education. In 1768 he produced his first tragedy, Amélise. The failure of this first attempt was fully compensated by the success of his Hamlet (1769), and Roméo et Juliette (1772). Œdipe chez Admète, imitated partly from Euripides and partly from Sophocles, appeared in 1778, and secured him in the following year the chair in the Academy left vacant by the death of Voltaire. Equally successful was Le Roi Lear in 1783. Macbeth in 1783 did not take so well, and Jean sans peur in 1791 was almost a failure; but Othello in 1792, supported by the acting of Talma, obtained immense applause. Its vivid picturing of desert life secured for Abufas, ou la famille arabe (1795), an original drama, a flattering reception. On the failure of a similar piece, Phédor et Vladimir ou la famille de Sibérie (1801), Ducis ceased to write for the stage; and the rest of his life was spent in quiet retirement at Versailles. He had been named a member of the Council of the Ancients in 1798, but he never discharged the functions of the office; and when Napoleon offered him a post of honour under the empire, he refused. Amiable, religious and bucolic, he had little sympathy with the fierce, sceptical and tragic times in which his lot was cast. “Alas!” he said in the midst of the Revolution, “tragedy is abroad in the streets; if I step outside of my door, I have blood to my very ankles. I have too often seen Atreus in clogs, to venture to bring an Atreus on the stage.” Though actuated by honest admiration of the great English dramatist, Ducis is not Shakespearian. His ignorance of the English language left him at the mercy of the translations of Pierre Letourneur (1736-1788) and of Pierre de la Place (1707-1793); and even this modified Shakespeare had still to undergo a process of purification and correction before he could be presented to the fastidious criticism of French taste. That such was the case was not, however, the fault of Ducis; and he did good service in modifying the judgment of his fellow countrymen. He did not pretend to reproduce, but to excerpt and refashion; and consequently the French play sometimes differs from its English namesake in everything almost but the name. The plot is different, the characters are different, the motif different, and the scenic arrangement different. To Othello, for instance, he wrote two endings. In one of them Othello was enlightened in time and Desdemona escaped her tragic fate. Le Banquet de l’amitié, a poem in four cantos (1771), Au roi de Sardaigne (1775), Discours de réception à l’académie française (1779), Épître à l’amitié (1786), and a Recueil de poésies (1809), complete the list of Ducis’s publications.

An edition of his works in three volumes appeared in 1813; Œuvres posthumes were edited by Campenon in 1826; and Hamlet, Œdipe chez Admète, Macbeth and Abufar are reprinted in vol. ii. of Didot’s Chefs-d’œuvre tragiques. See Onésime Leroy, Étude sur la personne et les écrits de Ducis (1832), based on Ducis’s own memoirs preserved in the library at Versailles; Sainte-Beuve, Causeries du lundi, t. vi., and Nouveaux lundis, t. iv.; Villemain, Tableau de la litt. au XVIIIe siècle.

DUCK. (1) (From the verb “to duck,” to dive, put the head under water, in reference to the bird’s action, cf. Dutch duiker, Ger. Taucher, diving-bird, duiken, tauchen, to dip, dive, Dan. dukand, duck, and Ger. Ente, duck; various familiar and slang usages are based on analogy with the bird’s action), the general English name for a large number of birds forming the greater part of the family Anatidae of modern ornithologists. Technically the term duck is restricted to the female, the male being called drake (cognate with the termination of Ger. Enterich), and in one species mallard (Fr. Malart).

The Anatidae may be at once divided into six more or less well marked subfamilies—(1) the Cygninae or swans, (2) the Anserinae or geese—which are each very distinct, (3) the Anatinae or freshwater-ducks, (4) those commonly called Fuligulinae or sea-ducks, (5) the Erismaturinae or spiny-tailed ducks, and (6) the Merginae or mergansers.

The Anatinae are the typical group, and it is these only that are considered here. We start with the Anas boschas of Linnaeus, the common wild duck, which from every point of view is by far the most important species, as it is the most plentiful, the most widely distributed, and the best known—being indeed the origin of all the British domestic breeds. It inhabits the greater part of the northern hemisphere, reaching in winter so far as the Isthmus of Panama in the New World, and in the Old being abundant at the same season in Egypt and north-western India, while in summer it ranges throughout the Fur-Countries, Greenland, Iceland, Lapland and Siberia. Most of those which fill British markets are no doubt bred in more northern climes, but a considerable proportion of them are yet produced in the British Islands, though not in anything like the numbers that used to be supplied before the draining of the great fen-country and other marshy places. The wild duck pairs very early in the year—the period being somewhat delayed by hard weather, and the ceremonies of courtship, which require some little time. Soon after these are performed, the respective couples separate in search of suitable nesting-places, which are generally found, by those that remain with us, about the middle of March. The spot chosen is sometimes near a river or pond, but often very far removed from water, and it may be under a furze-bush, on a dry heath, at the bottom of a thick hedge-row, or even in any convenient hole in a tree. A little dry grass is generally collected, and on it the eggs, from 9 to 11 in number, are laid. So soon as incubation commences the mother begins to divest herself of the down which grows thickly beneath her breast-feathers, and adds it to the nest-furniture, so that the eggs are deeply imbedded in this heat-retaining substance—a portion of which she is always careful to pull, as a coverlet, over her treasures when she quits them for food. She is seldom absent from the nest, however, but once, or at most twice, a day, and then she dares not leave it until her mate, after several circling flights of observation, has assured her she may do so unobserved. Joining him the pair betake themselves to some quiet spot where she may bathe and otherwise refresh herself. Then they return to the nest, and after cautiously reconnoitring the neighbourhood, she loses no time in reseating herself on her eggs, while he, when she is settled, repairs again to the waters, and passes his day listlessly in the company of his brethren, who have the same duties, hopes and cares. Short and infrequent as are the absences of the duck when incubation begins, they become shorter and more infrequent towards its close, and for the last day or two of the 631 28 necessary to develop the young it is probable that she will not stir from the nest at all. When all the fertile eggs are hatched her next care is to get the brood safely to the water. This, when the distance is great, necessarily demands great caution, and so cunningly is it done that but few persons have encountered the mother and offspring as they make the dangerous journey.1 If disturbed the young instantly hide as they best can, while the mother quacks loudly, feigns lameness, and flutters off to divert the attention of the intruder from her brood, who lie motionless at her warning notes. Once arrived at the water they are comparatively free from harm, though other perils present themselves from its inmates in the form of pike and other voracious fishes, which seize the ducklings as they disport in quest of insects on the surface or dive beneath it. Throughout the summer the duck continues her care unremittingly, until the young are full grown and feathered; but it is no part of the mallard’s duty to look after his offspring, and indeed he speedily becomes incapable of helping them, for towards the end of May he begins to undergo his extraordinary additional moult, loses the power of flight, and does not regain his full plumage till autumn. About harvest-time the young are well able to shift for themselves, and then resort to the corn-fields at evening, where they fatten on the scattered grain. Towards the end of September or beginning of October both old and young unite in large flocks and betake themselves to the larger waters. If long-continued frost prevail, most of the ducks resort to the estuaries and tidal rivers, or even leave these islands almost entirely. Soon after Christmas the return-flight commences, and then begins anew the course of life already described.

For the farmyard varieties, descending from Anas boschas, see Poultry. The domestication of the duck is very ancient. Several distinct breeds have been established, of which the most esteemed from an economical point of view are those known as the Rouen and Aylesbury; but perhaps the most remarkable deviation from the normal form is the so-called penguin-duck, in which the bird assumes an upright attitude and its wings are much diminished in size. A remarkable breed also is that often named (though quite fancifully) the “Buenos-Ayres” duck, wherein the whole plumage is of a deep black, beautifully glossed or bronzed. But this saturation, so to speak, of colour only lasts in the individual for a few years, and as the birds grow older they become mottled with white, though as long as their reproductive power lasts they “breed true.” The amount of variation in domestic ducks, however, is not comparable to that found among pigeons, no doubt from the absence of the competition which pigeon-fanciers have so long exercised. One of the most curious effects of domestication in the duck, however, is, that whereas the wild mallard is not only strictly monogamous, but, as Waterton believed, a most faithful husband, remaining paired for life, the civilized drake is notoriously polygamous.

Very nearly allied to the common wild duck are a considerable number of species found in various parts of the world in which there is little difference of plumage between the sexes—both being of a dusky hue—such as Anas obscura, the commonest river-duck of America, A. superciliosa of Australia, A. poecilorhyncha of India, A. melleri of Madagascar, A. xanthorhyncha of South Africa, and some others.

Among the other genera of Anatinae, we must content ourselves by saying that both in Europe and in North America there are the groups represented by the shoveller, garganey, gadwall, teal, pintail and widgeon—each of which, according to some systematists, is the type of a distinct genus. Then there is the group Aix, with its beautiful representatives the wood-duck (A. sponsa) in America and the mandarin-duck (A. galericulata) in Eastern Asia. Besides there are the sheldrakes (Tadorna), confined to the Old World and remarkably developed in the Australian Region; the musk-duck (Cairina) of South America, which is often domesticated and in that condition will produce hybrids with the common duck; and finally the tree-ducks (Dendrocygna), which are almost limited to the tropics. (For duck-shooting, see Shooting.)

2 (Probably derived from the Dutch doeck, a coarse linen material, cf. Ger. Tuch, cloth), a plain fabric made originally from tow yarns. The cloth is lighter than canvas or sailcloth, and differs from these in that it is almost invariably single in both warp and weft. The term is also used to indicate the colour obtained at a certain stage in the bleaching of flax yarns; it is a colour between half-white and cream, and this fact may have something to do with the name. Most of the flax ducks (tow yarns) appear in this colour, although quantities are bleached or dyed. Some of the ducks are made from long flax, dyed black, and used for kit-bags, while the dyed tow ducks may be used for inferior purposes. The fabric, in its various qualities and colours, is used for an enormous variety of purposes, including tents, wagon and motor hoods, light sails, clothing, workmen’s overalls, bicycle tubes, mail and other bags and pocketings. Russian duck is a fine white linen canvas.

1 When ducks breed in trees, the precise way in which the young get to the ground is still a matter of uncertainty. The mother is supposed to convey them in her bill, and most likely does so, but they are often simply allowed to fall.

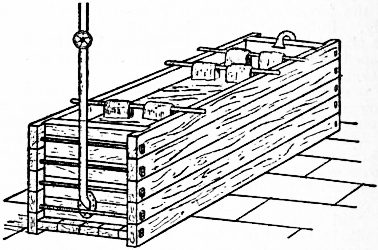

DUCKING and CUCKING STOOLS, chairs used for the punishment of scolds, witches and prostitutes in bygone days. The two have been generally confused, but are quite distinct. The earlier, the Cucking-stool1 or Stool of Repentance, is of very ancient date, and was used by the Saxons, who called it the Scealding or Scolding Stool. It is mentioned in Domesday Book as in use at Chester, being called cathedra stercoris, a name which seems to confirm the first of the derivations suggested in the footnote below. Seated on this stool the woman, her head and feet bare, was publicly exposed at her door or paraded through the streets amidst the jeers of the crowd. The Cucking-stool was used for both sexes, and was specially the punishment for dishonest brewers and bakers. Its use in the case of scolding women declined on the introduction in the middle of the 16th century of the Scold’s Bridle (see Branks), and it disappears on the introduction a little later of the Ducking-stool. The earliest record of the use of this latter is towards the beginning of the 17th century. It was a strongly made wooden armchair (the surviving specimens are of oak) in which the culprit was seated, an iron band being placed around her so that she should not fall out during her immersion. Usually the chair was fastened to a long wooden beam fixed as a seesaw on the edge of a pond or river. Sometimes, however, the Ducking-stool was not a fixture but was mounted on a pair of wooden wheels so that it could be wheeled through the streets, and at the river-edge was hung by a chain from the end of a beam. In sentencing a woman the magistrates ordered the number of duckings she should have. Yet another type of Ducking-stool was called a tumbrel. It was a chair on two wheels with two long shafts fixed to the axles. This was pushed into the pond and then the shafts released, thus tipping the chair up backwards. Sometimes the punishment proved fatal, the unfortunate woman dying of shock. Ducking-stools were used in England as late as the beginning of the 19th century. The last recorded cases are those of a Mrs Ganble at Plymouth (1808); of Jenny Pipes, “a notorious scold” (1809), and Sarah Leeke (1817), both of Leominster. In the last case the water in the pond was so low that the victim was merely wheeled round the town in the chair.

See W. Andrews, Old Time Punishments (Hull, 1890); A.M. Earle, Curious Punishments of Bygone Days (Chicago, 1896); W.C. Hazlitt, Faiths and Folklore (London, 1905); Llewellynn Jewitt in The Reliquary, vols. i. and ii. (1860-1862); Gentleman’s Magazine for 1732.

1 Probably from “cuck,” to void excrement; but variously connected with Fr. coquin, rascal.

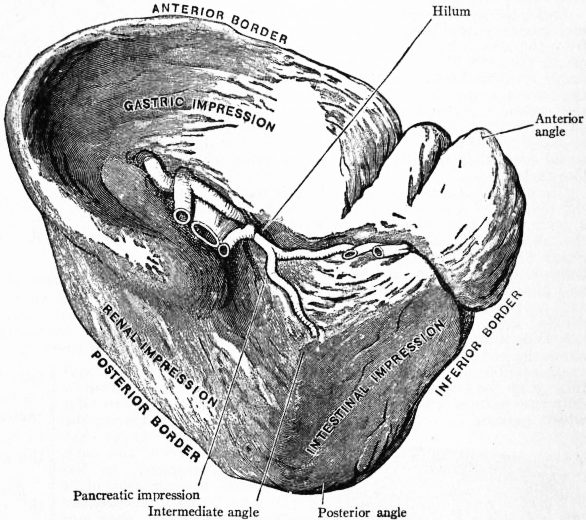

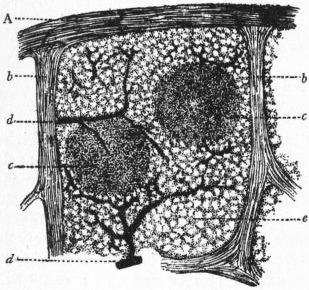

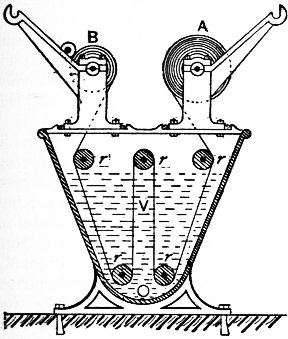

DUCKWEED, the common botanical name for species of Lemna which form a green coating on fresh-water ponds and ditches. The plants are of extremely simple structure and are the smallest and least differentiated of flowering plants. They consist of a so-called “frond”—a flattened green more or less oval structure which emits branches similar to itself from lateral pockets at or near the base. From the under surface a root with a well-developed sheath grows downwards into the water. The flowers, which are rarely found in Britain, are 632 developed in one of the lateral pockets. The inflorescence is a very simple one, consisting of one or two male flowers each comprising a single stamen, and a female flower comprising a flask-shaped pistil. The order Lemnaceae to which they belong is regarded as representing a very reduced type nearly allied to the Aroids. It is represented in Britain by four species of Lemna, and a still smaller and simpler plant, Wolffia, in which the fronds are only one-twentieth of an inch long and have no roots.

|

|

1, Lemna minor (Lesser Duckweed) nat. size. 2, Plant in flower. 3, Inflorescence containing two male flowers each of one stamen, and a female flower, the whole enclosed in a sheath. 4, Wolffia arrhiza. (2, 3, 4 enlarged.) |