DRESS

AS A FINE ART.

WITH SUGGESTIONS ON CHILDREN'S DRESS.

By MRS. MERRIFIELD.

WITH AN INTRODUCTION ON

Head Dress.

By PROF. FAIRHOLT.

BOSTON:

JOHN P. JEWETT AND COMPANY.

CLEVELAND, OHIO:

JEWETT, PROCTOR, AND WORTHINGTON.

1854.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1853, by

JOHN P. JEWETT & CO.,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts

PRESS OF GEO. C. RAND,

WOOD CUT AND BOOK PRINTER,

CORNHILL, BOSTON.

STEREOTYPED AT THE

BOSTON STEREOTYPE FOUNDRY.

The fact that we derive our styles of dress from the same source as the English, and that the work of Mrs. Merrifield has been circulated among the forty thousand subscribers of the “London Art Journal,” might perhaps be deemed sufficient apology for offering it in its present form to the American public. It has received the unqualified approbation of the best publications in this country;—entire chapters having been copied into the periodicals of the day; this added to the above, and also to the high standing of the author, has induced the publishers to offer it to the great reading public of this country.

The chapter on Head-dresses, which commences the book, is of much interest in itself, and affords an explanation of many of the descriptions in the body of the work.

The closing chapter, on Children's Dress, by Mrs. Merrifield, will be deemed of more value by most persons than the cost of the entire work.

A few verbal alterations only have been made in the original;—the good sense of every reader will enable him to understand the local allusions, and where they belong to England alone, to make the application.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| DESCRIPTION OF HEAD-DRESSES, | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| DRESS, AS A FINE ART, | 10 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE HEAD, | 53 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| THE DRESS, | 61 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| THE FEET, | 73 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| REMARKS ON PARTICULAR COSTUMES, | 84 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| ORNAMENT—ECONOMY, | 95 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| SOME THOUGHTS ON CHILDREN'S DRESS.—BY MRS. MERRIFIELD, | 121 |

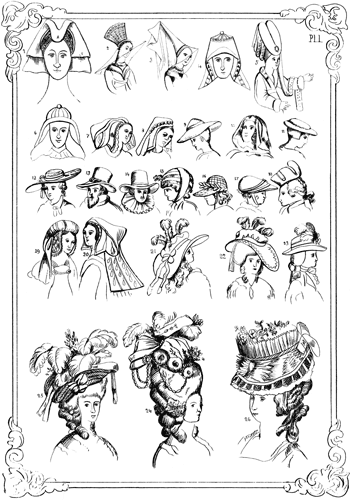

| PLATE I. | |

| Figure 1. | Head-dress of Lady Ardene. |

| 2. | A kind of hat. |

| 3. | Steeple head-dress. |

| 4, 6. | Head-dresses of Lady Rolestone. |

| 5. | Heart-shaped head-dresses. |

| 7, 8. | Head-dresses of the time of Henry VIII. |

| 9, 11. | Hats of the time of George II. |

| 10. | Nithsdale hood. |

| 12. | Hat of the time of William III. |

| 13, 14. | Hats of the time of Charles I. |

| 15, 16, 17. | Head-dresses of 1798. |

| 18. | Head-dress of 1700. |

| 19. | Head-dress of the time of Henry VI. |

| 20. | Combination of figs. 7, 8. |

| 21, 22. | Hats for ladies in 1786. |

| 23. | Style of 1785. |

| 24, 25, 26. | Style of 1782. |

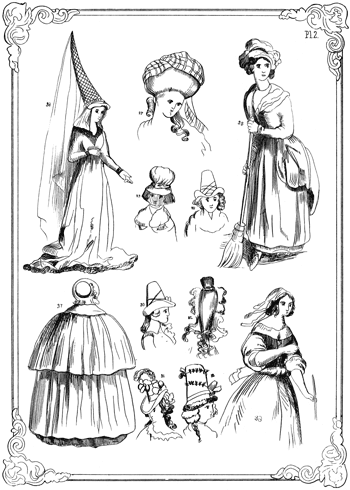

| PLATE II. | |

| Figure 27. | Style of 1782. |

| 28, 30. | Head-dress of 1790. |

| 29. | Head-dress of the French peasantry. |

| 31. | Fashion of 1791. |

| 32, 33. | Fashion of 1789. |

| 36. | Head-dress of the commencement of the present century. |

| 35. | English housemaid. |

| 37. | Gigot sleeves, with cloak worn over. |

| 38. | From a picture in the Louvre. |

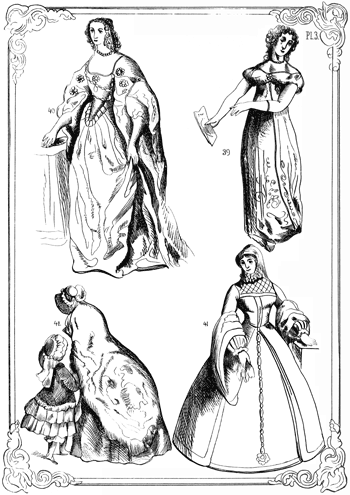

| PLATE III. | |

| Figure 39. | Dress, with short waist and sleeves. |

| 41. | Dress of the mother of Henry IV. |

| 40. | Dress of Henrietta Maria. |

| 42. | From the “Illustrated London News.” |

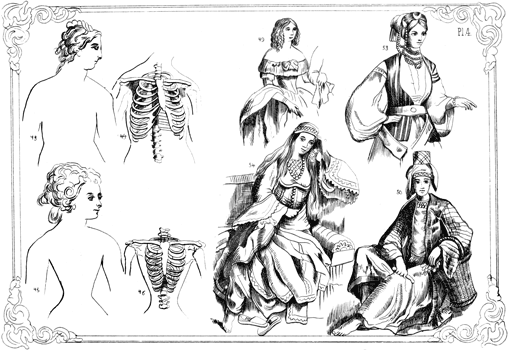

| PLATE IV. | |

| Figures 43, 44. | From the plates of Sommaering, shows the waist of the Venus of antiquity. |

| 45, 46. | The waist of a modern lady, from the above. |

| 49. | From the “London News.” |

| 50. | Woman of Mitylene. |

| 53. | Algerine woman. |

| 54. | The archon's wife. |

| PLATE V. | |

| Figure 47. | Athenian peasant. |

| 48. | Shepherdess of Arcadia. |

| 51. | Athenian woman. |

| 52. | French costume of the tenth century. |

| 62. | Lady of the time of Henry V. |

| PLATE VI. | |

| Figure 55. | After Parmegiano. |

| 56. | Titian's daughter. |

| 57. | Lady Harrington. |

| 59. | Roman peasant. |

| 61. | Gigot sleeves. |

| PLATE VII. | |

| Figure 63. | From Bonnard's Costumes. |

| 64. | Sancta Victoria. |

| 65. | Anne, Countess of Chesterfield, from Vandyck. |

| 67. | Woman of Markinitza. |

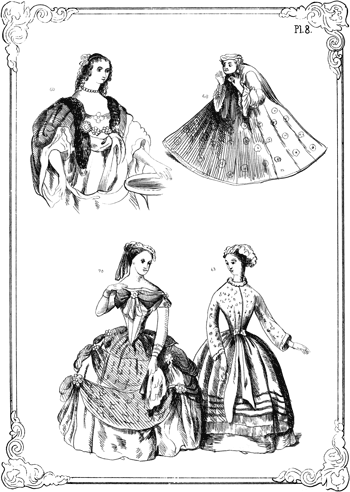

| PLATE VIII. | |

| Figure 60. | Lady Lucy Percy, from Vandyck. |

| 69, 70. | By Jules David, in “Le Moniteur de la Mode.” |

| 68. | The hoop, after Hogarth. |

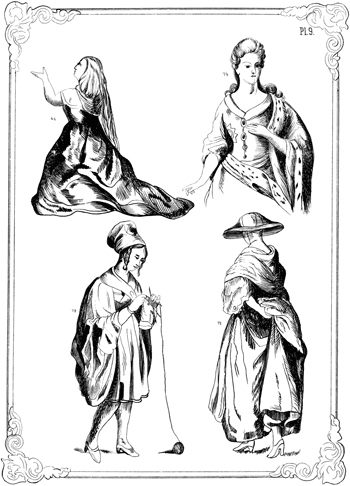

| PLATE IX. | |

| Figure 66. | From Rubens's “Descent from the Cross.” |

| 71. | From a drawing by Gainsborough. |

| 72. | Woman of Myconia. |

| 74. | Queen Anne. |

| PLATE X. | |

| Figure 73. | Charlotte de la Tremouille. |

| 75. | After Gainsborough. |

| 76. | After Gainsborough. |

| 77. | Costume of Mrs. Bloomer. |

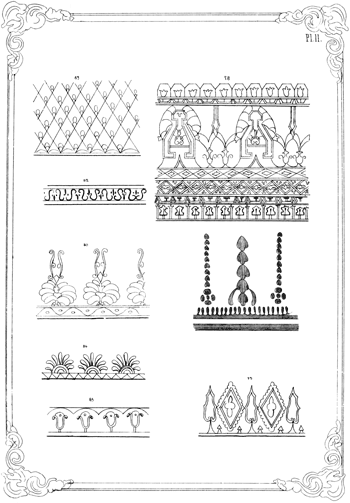

| PLATE XI. | |

| Figure 78. | From the embroidery on fig. 47, pl. 5. |

| 79. | From the sleeve of the same dress, above. |

| 80. | From the sleeve of the pelisse. |

| 81. | The pattern embroidered from the waist to the skirt of the dress, fig. 51, pl. 5. |

| 82. | The border of the shawl, fig. 51. |

| 83. | Sleeve of the same, figure 51. |

| 84. | Design on the apron, fig. 48, pl. 5. |

| 85. | From the border of the same dress, fig. 48. |

| PLATE XII. | |

| Figure 86. | Pattern round the hem of the long under dress, fig. 51, pl. 5. |

| 87, 88. | Borders of shawls. |

| 89. | Infant's dress, exhibited at the World's Fair in London. |

| 90, 91. | From “Le Moniteur de la Mode,” by Jules David and Réville, published at Paris, London, New York, and St. Petersburg. |

CHAPTER I.

DESCRIPTION OF HEAD-DRESSES.

Fig. 1 is a front view of a head-dress of Lady Arderne, (who died about the middle of the fifteenth century.) The caul of the head-dress is richly embroidered, the veil above being supported by wires, in the shape of a heart, with double lappets behind the head, which are sometimes transparent, as if made of gauze.

Such gauze veils, or rather coverings for the head-dress, are frequently seen in the miniatures of MSS. Figs. 2, 3, are here selected from the royal MS. In Fig. 3, the steeple head-dress of the lady is entirely covered by a thin veil of gauze, which hangs from its summit, and projects over her face. Fig. 2 has a sort of hat, widening from its base, and made of cloth of gold, richly set with stones. Such jewelled head-dresses are represented on the heads of noble ladies, and are frequently ornamented in the most beautiful manner, with stones of various tints.

The slab to the memory of John Rolestone, Esq., sometime Lord of Swarston, and Sicili, his wife, in Swarkstone Church, Derbyshire, who died in 1482, gives the head-dress of the said Sicili as represented in Fig. 6. It is a simple cap, radiating in gores over the head, having a knob in its centre and a close falling veil of cloth affixed round the back. It seems to have been constructed as much for comfort as for show: the same remark may be applied to Fig. 4, which certainly cannot be recommended for its beauty, being a stunted cone, with a back veil closely fitting about the neck, and very sparingly ornamented; it was worn by Mary, wife of John Rolestone, who died in 1485. These may both have been plain country ladies, far removed from London, and little troubled with its fashionable freaks. Fig. 5 represents the fashionable head-dress of the last days of the house of York. It has been termed the heart-shaped head-dress, from the appearance it presents when viewed in front, which resembles that of a heart, and sometimes a crescent. It is made of black silk or velvet, ornamented with gold studs, and having a jewel over the forehead. It has a long band or lappet, such as the gentlemen then wore affixed to their hats. Figs. 7 and 8 represent head-dresses worn in the time of Henry VIII. These are a sort of cap, which seem to combine coverchief and hood. Fig. 7 was at this time the extreme of fashion. It is edged with lace, and ornamented with jewelry, and has altogether a look of utter unmeaningness and confusion of form. Fig. 8 has a hood easier of comprehension, but no whit better in point of elegance than her predecessors; it fits the head closely, having pendent jewels round the bottom and crossing the brow. Figs. 9 and 11 are hats of a very simple style, such as were worn during the reign of George II., when an affected simplicity, or milk-maiden look, was coveted by the ladies, both high and low. The hood worn by Fig. 10 was a complete envelope for the head, and was used in riding, or travelling, as well as in walking in the parks. These were called Nithsdales, because Lady Nithsdale covered her husband's face with one of them, after dressing him in her clothes, and thus disguised he escaped from the Tower. Fig. 12 represents a hat worn during the reign of William III. by a damsel who was crying, “Fair cherries, at sixpence a pound!” It is of straw, with a ribbon tied around it in a simple and tasteful manner; the hat is altogether a light and graceful affair, and its want of obtrusiveness is perhaps its chief recommendation. Figs. 13 and 14 are hats such as were worn by citizens and their wives during the reigns of James and Charles I. Figs. 15, 16, 17, were such head-dresses as were in vogue in 1798. Fig. 15 was of a deep orange color, with bands of dark chocolate brown; a bunch of scarlet tufts came over the forehead, and it was held on the head by a kerchief of white muslin tied beneath the chin. Fig. 16 is a straw bonnet, the crown decorated with red perpendicular stripes, the front over the face plain, and a row of laurel leaves surrounds the head; a lavender-colored tie secures it under the chin. Bonnets somewhat similar to those now worn were fashionable two years previous to this; yet a small, low-crowned hat, like the one in Fig. 17, was as much patronized as any head-dress had ever been.

Cocked hats, such as is represented in Fig. 18, were worn by the gentlemen in the last part of the year 1700. Fig. 19 represents one of the head-dresses worn during the reign of Henry VI. It is a combination of coverchief and turban. Fig. 20 is a combination of the head-dress of Fig. 7 with the lappeted hood of Fig. 8. In 1786, a very large-brimmed hat became fashionable with the ladies, and continued in vogue for the next two years; an idea of the back view of it is given in Fig. 21, and a front view in Fig. 22. It was decorated with triple feathers, and a broad band of ribbon was tied in a bow behind, and allowed to stream down the back. The elegance of turn which the brim of such a hat afforded was completely overdone by the enormity of its proportion; and the shelter it gave the face can now be considered as the only recommendation of this fashion. The hat worn by Fig. 23 was the style of 1785. Feathers were then much in favor, and a poet of the time writes of the ladies,—

Undertakers have got in the milliner's place;

With hands sacrilegious they've plundered the dead,

And transferred the gay plumes from the hearse to the head.”

Fig. 24 represents the head-dress worn in 1782. At no period in the history of the world was any thing more absurd in head-dress than the one here depicted. The body of this erection was formed of tow, over which the hair was turned, and false hair added in great curls; bobs and ties, powdered to profusion, then hung all over with vulgarly large rows of pearls, or glass beads, fit only to decorate a chandelier; flowers as obtrusive were stuck about this heap of finery, which was surmounted by broad silken bands and great ostrich feathers, until the head-dress of a lady added three feet to her stature, and “the male sex,” to use the words of the “Spectator,” “became suddenly dwarfed beside her.” To effect this, much time and trouble were wasted, and great personal annoyance was suffered. Heads, when properly dressed, “kept for three weeks,” as the barbers quaintly phrased it; that they would not really “keep” longer, may be seen by the many receipts they gave for the destruction of insects, which bred in the flour and pomatum so liberally bestowed upon them. Fig. 25 is another fashionable outdoor head-dress. Fig. 26 represents one of the hats invented to cover the head when full dressed. It is as extravagant as the head-dresses. It is a large but light compound of gauze, wire, ribbons, and flowers, sloping over the forehead, and sheltering the head entirely by its immensity. Fig. 27 shows how immensely globular the head of a lady had become; it swells all around like a huge pumpkin, and curls of a corresponding size aid in the caricature which now passed as fashionable taste. As if this were not load enough for the fair shoulders of the softer sex, it is swathed with a huge veil or scarf, giving the wearer an exceedingly top-heavy look. In 1790, the ladies appeared in hats similar to those worn by the gentlemen in 1792; these are represented in Figs. 28 and 30. They were gayly decorated with gold strings, and tassels, crossed and recrossed over the crown. The brims were broad, raised at the sides, and pointed over the face in a manner not inelegant. Fig. 29 has the tall, ugly bonnet, copied from the French peasantry; a long gauze border is attached to the edges, which hangs like a veil around the face, and partially conceals it. A hat of a very piquant character was adopted by the ladies in 1791, of which a specimen is given in Fig. 31. It is decorated with bows, and a large feather nods not ungracefully over the crown from behind. A person with good face and figure must have looked becomingly beneath it. Fig. 32 is an example of the bad taste which still peeped forth. It is one of the most fashionable head-dresses worn in 1789, and is the back view of a lady's head, surmounted by a very small cap or hat, puffed round with ribbon; the hair is arranged in a long, straight bunch down the neck, where it is tied by a ribbon, and flows in curls beneath; long curls repose one on each shoulder, while the hair at the sides of the head is frizzed out on each side in a most fantastic form. The hat of Fig. 33, shaped like a chimney pot, and decorated with small tufts of ribbon, and larger bows, which fitted on a lady's head like the cover on a canister, was viewed with “marvellous favor” by many a fair eye, in the year 1789. It was sometimes bordered with lace, as in Fig. 29, thus hiding the entire head, and considerably enhancing its ugliness.

CHAPTER II.

DRESS, AS A FINE ART.

In a state so highly civilized as that in which we live, the art of dress has become extremely complicated. That it is an art to set off our persons to the greatest advantage must be generally admitted, and we think it is one which, under certain conditions, may be studied by the most scrupulous. An art implies skill and dexterity in setting off or employing the gifts of nature to the greatest advantage, and we are surely not wrong in laying it down as a general principle, that every one may endeavor to set off or improve his or her personal appearance, provided that, in doing so, the party is guilty of no deception. As this proposition may be liable to some misconstruction, we will endeavor to explain our meaning.

In the first place, the principle is acted upon by all who study cleanliness and neatness, which are universally considered as positive duties, that are not only conducive to our own comfort, but that society has a right to expect from us. Again: the rules of society require that to a certain extent we should adopt those forms of dress which are in common use, but our own judgment should be exercised in adapting these forms to our individual proportions, complexions, ages, and stations in society. In accomplishing this object, the most perfect honesty and sincerity of purpose may be observed. No deception is to be practised, no artifice employed, beyond that which is exercised by the painter, who arranges his subjects in the most pleasing forms, and who selects colors which harmonize with each other; and by the manufacturer, who studies pleasing combinations of lines and colors. We exercise taste in the decoration and arrangement of our apartments and in our furniture, and we are equally at liberty to do so with regard to our dress; but we know that taste is not an instinctive perception of the beautiful and agreeable, but is founded upon the observance of certain laws of nature. When we conform to these laws, the result is pleasing and satisfactory; when we offend against them, the contrary effect takes place. Our persons change with our years; the child passes into youth, the youth into maturity, maturity changes into old age. Every period of life has its peculiar external characteristics, its pleasures, its pains, and its pursuits. The art of dress consists in properly adapting our clothing to these changes.

We violate the laws of nature when we seek to repair the ravages of time on our complexions by paint, when we substitute false hair for that which age has thinned or blanched, or conceal the change by dyeing our own gray hair; when we pad our dress to conceal that one shoulder is larger than the other. To do either is not only bad taste, but it is a positive breach of sincerity. It is bad taste, because the means we have resorted to are contrary to the laws of nature. The application of paint to the skin produces an effect so different from the bloom of youth, that it can only deceive an unpractised eye. It is the same with the hair: there is such a want of harmony between false hair and the face which it surrounds, especially when that face bears the marks of age, and the color of the hair denotes youth, that the effect is unpleasing in the extreme. Deception of this kind, therefore, does not answer the end which it had in view; it deceives nobody but the unfortunate perpetrator of the would-be deceit. It is about as senseless a proceeding as that of the goose in the story, who, when pursued by the fox, thrust her head into a hedge, and thought that, because she could no longer see the fox, the fox could not see her. But in a moral point of view it is worse than silly; it is adopted with a view to deceive; it is acting a lie to all intents and purposes, and it ought to be held in the same kind of detestation as falsehood with the tongue. Zimmerman has an aphorism which is applicable to this case—“Those who conceal their age do not conceal their folly.”

The weak and vain, who hope to conceal their age by paint and false hair, are, however, morally less culpable than another class of dissemblers, inasmuch as the deception practised by the first is so palpable that it really deceives no one. With regard to the other class of dissemblers, we feel some difficulty in approaching a subject of so much delicacy. Yet, as we have stated that we are at liberty to improve our natural appearance by well-adapted dress, we think it our duty to speak out, lest we should be considered as in any way countenancing deception. We allude to those physical defects induced by disease, which are frequently united to great beauty of countenance, and which are sometimes so carefully concealed by the dress, that they are only discovered after marriage.

Having thus, we hope, established the innocence of our motives, we shall proceed to mention the legitimate means by which the personal appearance may be improved by the study of the art of dress.

Fashion in dress is usually dictated by caprice or accident, or by the desire of novelty. It is never, we believe, based upon the study of the figure.

It is somewhat singular that while every lady thinks herself at liberty to wear any textile fabric or any color she pleases, she considers herself bound to adopt the form and style of dress which the fashion of the day has rendered popular. The despotism of fashion is limited to form, but color is free. We have shown, in another essay, (see closing chapter,) what licentiousness this freedom in the adoption and mixture of colors too frequently induces. We have also shown that the colors worn by ladies should be those which contrast or harmonize best with their individual complexions, and we have endeavored to make the selection of suitable colors less difficult by means of a few general rules founded upon the laws of harmony and contrast of colors. In the present essay, we propose to offer some general observations on form in dress. The subject is, however, both difficult and complicated, and as it is easier to condemn than to improve or perfect, we shall more frequently indicate what fashions should not be adopted, than recommend others to the patronage of our readers.

The immediate objects of dress are twofold—namely, decency and warmth; but so many minor considerations are suffered to influence us in choosing our habiliments, that these primary objects are too frequently kept out of sight. Dress should be not only adapted to the climate, it should also be light in weight, should yield to the movements of the body, and should be easily put on or removed. It should also be adapted to the station in society, and to the age, of the individual. These are the essential conditions; yet in practice how frequently are they overlooked; in fact, how seldom are they observed! Next in importance are general elegance of form, harmony in the arrangement and selection of the colors, and special adaptation in form and color to the person of the individual. To these objects we purpose directing the attention of the reader.

It is impossible, within the limits we have prescribed ourselves, to enter into the subject of dress minutely; we can only deal with it generally, and lay down certain broad principles for our guidance. If these are observed, there is still a wide margin left for fancy and fashion. These may find scope in trimmings and embroidery; the application of which, however, must also be regulated by good taste and knowledge. The physical variety in the human race is infinite; so are the gradations and combinations of color; yet we expect a few forms of dress to suit every age and complexion! Instead of the beautiful, the graceful, and the becoming, what are the attractions offered by the dress makers? What are the terms used to invite the notice of customers? Novelty and distinction. The shops are “Magasins de Nouveautés,” the goods are “distingués,” “recherchés,” “nouveaux,” “the last fashion.” The new fashions are exhibited on the elegant person of one of the dress maker's assistants, who is selected for this purpose, and are adopted by the purchaser without reflecting how much of the attraction of the dress is to be ascribed to the fine figure of the wearer, how much to the beauty of the dress, or whether it will look equally well on herself. So the fashion is set, and then it is followed by others, until at last it becomes singular not to adopt some modification of it, although the extreme may be avoided. The best dressers are generally those who follow the fashions at a great distance.

Fashion is the only tyrant against whom modern civilization has not carried on a crusade, and its power is still as unlimited and despotic as it ever was. From its dictates there is no appeal; health and decency are alike offered up at the shrine of this Moloch. At its command its votaries melt under fur boas in the dog days, and freeze with bare necks and arms, in lace dresses and satin shoes, in January. Then, such is its caprice, that no sooner does a fashion become general, than, let its merits or beauties be ever so great, it is changed for one which perhaps has nothing but its novelty to recommend it. Like the bed of Procrustes, fashions are compelled to suit every one. The same fashion is adopted by the tall and the short, the stout and the slender, the old and the young, with what effect we have daily opportunities of observing.

Yet, with all its vagaries, fashion is extremely aristocratic in its tendencies. Every change emanates from the highest circles, who reject it when it has descended to the vulgar. No new form of dress was ever successful which did not originate among the aristocracy. From the ladies of the court, the fashions descend through all the ranks of society, until they at last die a natural death among the cast-off clothes of the housemaid. Fig. 35.

Had the Bloomer costume, which has obtained so much notoriety, been introduced by a tall and graceful scion of the aristocracy, either of rank or talent, instead of being at first adopted by the middle ranks, it might have met with better success. We have seen that Jenny Lind could introduce a new fashion of wearing the hair, and a new form of hat or bonnet, and Mme. Sontag a cap which bears her name. But it was against all precedent to admit and follow a fashion, let its merits be ever so great, that emanated from the stronghold of democracy. We are content to adopt the greatest absurdities in dress when they are brought from Paris, or recommended by a French name; but American fashions have no chance of success in aristocratic England. It is beginning at the wrong end.

The eccentricities of fashion are so great that they would appear incredible if we had not ocular evidence of their prevalence in the portraits which still exist. At one period we read of horned head-dresses, which were so large and high, that it is said the doors of the palace at Vincennes were obliged to be altered to admit Isabel of Bavaria (queen of Charles VI. of France) and the ladies of her suite. In the reign of Edward IV., the ladies' caps were three quarters of an ell in height, and were covered by pieces of lawn hanging down to the ground, or stretched over a frame till they resembled the wings of a butterfly.[1] At another time the ladies' heads were covered with gold nets, like those worn at the present day. Then, again, the hair, stiffened with powder and pomatum, and surmounted by flowers, feathers, and ribbons, was raised on the top of the head like a tower. Such head-dresses were emphatically called “têtes.” (See chapter on Head-Dress.) Fig. 36. But to go back no farther than the beginning of the present century, where Mr. Fairholt's interesting work on British Costume terminates, what changes have we to record! The first fashion we remember was that of scanty clothing, when slender figures were so much admired, that many, to whom nature had denied this qualification, left off the under garments necessary for warmth, and fell victims to the colds and consumptions induced by their adoption of this senseless practice. To these succeeded waists so short that the girdles were placed almost under the arms, and as the dresses were worn at that time indecently low in the neck, the body of the dress was almost a myth. Fig. 39.

About the same time, the sleeves were so short, and the skirts so curtailed in length, that there was reason to fear that the whole of the drapery might also become a myth. A partial reaction then took place, and the skirts were lengthened without increasing the width of the dresses, the consequence of which was felt in the country, if not in the towns. Then woe to those who had to cross a ditch or a stile! One of two things was inevitable; either the unfortunate lady was thrown to the ground,—and in this case it was no easy matter to rise again,—or her dress was split up. The result depended entirely upon the strength of the materials of which the dress was composed. The next variation, the gigot sleeves, namely, were a positive deformity, inasmuch as they gave an unnatural width to the shoulders—a defect which was further increased by the large collars which fell over them, thus violating one of the first principles of beauty in the female form, which demands that this part of the body should be narrow; breadth of shoulder being one of the distinguishing characteristics of the stronger sex. We remember to have seen an engraving from a portrait, by Lawrence, of the late Lady Blessington, in which the breadth of the shoulders appeared to be at least three quarters of a yard. When a person of low stature, wearing sleeves of this description, was covered with one of the long cloaks, which were made wide at the shoulders to admit the sleeves, and to which was appended a deep and very full cape, the effect was ridiculous, and the outline of the whole mass resembled that of a haycock with a head on the top. Fig. 37. One absurdity generally leads to another; to balance the wide shoulders, the bonnets and caps were made of enormous dimensions, and were decorated with a profusion of ribbons and flowers. So absurd was the whole combination, that, when we meet with a portrait of this period, we can only look on it in the light of a caricature, and wonder that such should ever have been so universal as to be adopted at last by all who wished to avoid singularity. The transition from the broad shoulders and gigot sleeves to the tight sleeves and graceful black scarf was quite refreshing to a tasteful eye. These were a few of the freaks of fashion during the last half century. Had they been quite harmless, we might have considered them as merely ridiculous; but some of them were positively indecent, and others detrimental to health. We grieve especially for the former charge: it is an anomaly for which, considering the modest habits and education of our countrywomen, we find it difficult to account.

It is singular that the practice of wearing dresses cut low round the bust should be limited to what is called full dress, and to the higher, and, except in this instance, the more refined classes. Is it to display a beautiful neck and shoulders? No; for in this case it would be confined to those who had beautiful necks and shoulders to display. Is it to obtain the admiration of the other sex? That cannot be; for we believe that men look upon this exposure with unmitigated distaste, and that they are inclined to doubt the modesty of those young ladies who make so profuse a display of their charms. But if objectionable in the young, whose youth and beauty might possibly be deemed some extenuation, it is disgusting in those whose bloom is past, whether their forms are developed with a ripe luxuriance which makes the female figures of Rubens appear in comparison slender and refined, or whether the yellow skin, stretched over the wiry sinews of the neck, remind one of the old women whom some of the Italian masters were accustomed to introduce into their pieces, to enhance, by contrast, the beauty of the principal figures. Every period of life has a style of dress peculiarly appropriate to it, and we maintain that the uncovered bosom so conspicuous in the dissolute reign of Charles II., and from which, indeed, the reign of Charles I. was not, as we learn from the Vandyck portraits, exempt, should be limited, even in its widest extension, to feminine youth, or rather childhood.

If the dress be cut low, the bust should be covered after the modest and becoming fashion of the Italian women, whose highly picturesque costume painters are so fond of representing. The white drapery has a peculiarly good effect, placed as it is between the skin and richly-colored bodice. As examples of this style of dress, we may refer to Sir Charles Eastlake's “Pilgrims in Sight of Rome,” “The Grape Gatherer of Capri,” by Lehmann, and “The Dancing Lesson,” by Mr. Uwins, all of which are engraved in the Art Journal. Another hint may be borrowed from the Italian costume; we may just allude to it en passant. If bodices fitting to the shape must be worn, they should be laced across the front in the Italian fashion. Fig. 38. By this contrivance the dress will suit the figure more perfectly, and as the lace may be lengthened or shortened at pleasure, any degree of tightness may be given, and the bodice may be accommodated to the figure without compressing it. We find by the picture in the Louvre called sometimes “Titian's Mistress” that this costume is at least as old as Titian.

We have noticed the changes and transitions of fashion; we must mention one point in which it has continued constant from the time of William Rufus until the present day, and which, since it has entailed years of suffering, and in many instances has caused death, demands our most serious attention. We allude to the pernicious practice of tight lacing, which, as appears from contemporary paintings, was as general on the continent as in England.

The savage American Indian changes the shape of the soft and elastic bones of the skull of his infant by compressing it between two boards; the intelligent but prejudiced Chinese suffers the head to grow as nature formed it, but confines the foot of the female to the size of an infant's; while the highly-intellectual and well-informed European lady limits the growth of her waist by the pressure of the stays. When we consider the importance of the organs which suffer by these customs, surely we must acknowledge that the last is the most barbarous practice of the three.

We read in the history of France that the war-like Franks had such a dislike to corpulency that they inflicted a fine upon all who could not encircle their waists with a band of a certain length. How far this extraordinary custom may have been influential in introducing the predilection for small waists among the ladies of that country, as well as our own through the Norman conquerors, we cannot determine.

During the reign of Queen Elizabeth, the whole of the upper part of the body, from the waist to the chin, was encased in a cuirass of whalebone, the rigidity of which rendered easy and graceful movement impossible. The portrait of Elizabeth by Zucchero, with its stiff dress and enormous ruff, and which has been so frequently engraved, must be in the memory of all our readers. Stiffness was indeed the characteristic of ladies' dress at this period; the whalebone cuirass, covered with the richest brocaded silks, was united at the waist with the equally stiff vardingale or fardingale, which descended to the feet in the form of a large bell, without a single fold.

There is a portrait in the possession of Mr. Seymour Fitzgerald of the unfortunate Mary Queen of Scots, when quite young, in a dress of this kind; and one cannot help pitying the poor girl's rigid confinement in her stiff and uncomfortable dress. Fig. 41 represents Jeanne d'Albret, the mother of Henry IV., in the fardingale.

With Henrietta Maria dresses cut low in the front, (Fig. 40,) and flowing draperies, as we find them in the Vandyck portraits, came into fashion, but the figure still retained its stiffness around the waist, and has continued to do so through all the gradations and variations in shape and size of the hoop petticoat, and the scanty draperies of a later period, until the present day.[2]

If the proportions of the figure were generally understood, we should not hear of those deplorable, and in many cases fatal, results of tight lacing which have unfortunately been so numerous. So general has the pernicious practice been in this country, that a medical friend, who is professor of anatomy in a provincial academy, informed us that there was great difficulty in procuring a model whose waist had not been compressed by stays. That this is true of other localities besides that alluded to, may be inferred from a passage in Mr. Hay's lecture to the Society of Arts “On the Geometrical Principles of Beauty,” in which he mentions having, for the purpose of verifying his theory, employed “an artist who, having studied the human figure at the life academies on the continent, in London, and in Edinburgh, was well acquainted with the subject,” to make a careful drawing of the best living model which could be procured for the purpose. Mr. Hay observes, with reference to this otherwise fine figure, that “the waist has evidently been compressed by the use of stays.” In further confirmation of the prevalence of this bad habit, we may refer to Etty's pictures, in which this defect is but too apparent.

We fear, from Mr. Planché's extracts, that the evil was perpetuated by the poets and romance writers of the Norman period; and we are sure that the novelists of our own times have much to answer for on this score. Had they not been forever praising “taper waists,” tight lacing would have shared the fate of other fashions, and have been banished from all civilized society. Similar blame does not attach to the painter and sculptor. The creations of their invention are modelled upon the true principles of proportion and beauty, and in their works a small waist and foot are always accompanied by a slender form. In the mind of the poet and novelist the same associations may take place: when a writer describes the slender waist or small foot, he probably sees mentally the whole slender figure. The small waist is a proportionate part of the figure of his creation. But there is this difference between the painter and sculptor, and the novelist. The works of the first two address themselves to the eye, and every part of the form is present to the spectator; consequently, as regards form, nothing is left to the imagination. With respect to the poet and novelist, their creations are almost entirely mental ones; their descriptions touch upon a few striking points only, and are seldom so full as to fill up the entire form: much is, therefore, necessarily left to the imagination of the reader. Now, the fashion in which the reader will supply the details left undetermined by the poet and novelist, and fill up their scanty and shadowy outlines, depends entirely upon his knowledge of form; consequently, if this be small, the images which arise in the mind of the reader from the perusal of works of genius are confused and imperfect, and the proportions of one class of forms are assigned to, or mingled with, those of others, without the slightest regard to truth and nature. When we say, therefore, that writers leave much to the imagination, it may too frequently be understood, to the ignorance of the reader; for the imaginations of those acquainted with form and proportion, who generally constitute the minority, always create well-proportioned ideal forms; while the ideal productions of the uneducated, whether expressed by the pencil, the chisel, or the pen, are always ill proportioned and defective.

The most efficient method of putting an end to the practice of tight lacing will be, not merely to point out its unhealthiness, and even dangerous consequences, because these, though imminent, are uncertain,—every lady who resorts to the practice hoping that she, individually, may escape the penalty,—but to prove that the practice, so far from adding to the beauty of the figure, actually deteriorates it. This is an effect, not doubtful, like the former case, but an actual and positive fact; and, therefore, it supplies a good and sufficient reason, and one which the most obtuse intellect can comprehend, for avoiding the practice. Young ladies will sometimes, it is said, run the risk of ill health for the sake of the interest that in some cases attaches to “delicate health;” but is there any one who would like to be told that, by tight lacing, she makes her figure not only deformed, but positively ugly? This, however, is the plain unvarnished truth; and, by asserting it, we are striking at the root of the evil. The remedy is easy: give to every young lady a general knowledge of form, and of the principles of beauty as applied to the human frame, and when these are better understood, and acted on, tight lacing will die a natural death.

The study of form, on scientific principles, has hitherto been limited entirely to men; and if some women have attained this knowledge, it has been by their own unassisted efforts; that is to say, without the advantages which men derive from lectures and academical studies. In this, as in other acquirements, the pursuit of knowledge, as regards women, is always attended with difficulties. While fully concurring in the propriety of having separate schools for male and female students, we do think that a knowledge of form may be communicated to all persons, and that a young woman will not make the worse wife, or mother, for understanding the economy of the human frame, and for having acquired the power of appreciating its beauties. We fear that there are still some persons whose minds are so contracted as to think that, not only studies of this nature, but even the contemplation of undraped statuary, are derogatory to the delicacy and purity of the female mind; but we are satisfied that the thinking part of the community will approve the course we recommend. Dr. Southwood Smith, who is so honorably distinguished by his endeavors to promote the sanatory condition of the people, strenuously advocates the necessity of giving to all women a knowledge of the structure and functions of the body, with a view to the proper discharge of their duties as mothers. He remarks (Preface to “Philosophy of Health”) on this subject, “I look upon that notion of delicacy which would exclude women from knowledge calculated in an extraordinary degree to open, exalt, and purify their minds, and to fit them for the performance of their duties, as alike degrading to those to whom it affects to show respect, and debasing to the mind that entertains it.”

At the present time, the knowledge of what constitutes true beauty of form is, perhaps, best acquired by the contemplation of good pictures and sculpture. This may not be in the power of every body; casts, however, may be frequently obtained from the best statues; and many of the finest works of painting are rendered familiar to us by engravings. The Art Journal has done much in diffusing a taste for art, by the engravings it contains from statues, and from the fine works of English art in the “Vernon Gallery.” Engravings, however, can of course represent a statue in one point of view only; but casts are now so cheap as to be within the reach of all persons. Small models of the “Greek Slave” are not unfrequently offered by the Italian image venders for one shilling; and although these are not sharp enough to draw from, the form is sufficiently correct to study the general proportions of the figure; and as this figure is more upright than statues usually are, it may be found exceedingly useful for the above purpose. One of these casts, or, if possible, a sharper and better cast of a female figure, should be found on the toilette of every young lady who is desirous of obtaining a knowledge of the proportions and beauties of the figure.

We believe it will always be found that the beauty of a figure depends not only upon the symmetry of the parts individually, but upon the harmony and proportion of each part to the rest. The varieties of the human form have been classed under the general heads of the broad, the proportionate, and the slender.

The first betokens strength; and what beauty soever, of a peculiar kind, it may display in the figure of the Hercules, it is not adapted to set off the charms of the female sex. If, however, each individual part bears a proportionate relation to the whole, the figure will not be without its attraction. It is only when the proportions of two or three of the classes are united in one individual, that the figure becomes ungraceful and remarkable. The athletic—if the term may be applied to females—form of the country girl would appear ridiculous with the small waist, and the white and taper fingers, and small feet of the individuals who come under the denomination of slender forms. The tall and delicate figure would lose its beauty if united to the large and broad hands which pertain to the stronger type. A small waist and foot are as great a blemish to an individual of the broad variety as a large waist and foot are to the slender. “There is a harmony,” says Dr. Wampen, “between all the parts in each kind of form, but each integral is only suited to its own kind of form. True beauty consists not only in the harmony of the elements, but in their being suitable to the kind of form.” Were this fundamental truth but thoroughly understood, small waists and small feet would be at a discount. When they are recognized as small, they have ceased to be beautiful, because they are disproportionate. Where every part of a figure is perfectly proportioned to the rest, no single parts appear either large or small.

The ill effects of the stays in a sanatory point of view have been frequently pointed out, and we hope are now understood. It will, therefore, be unnecessary to enlarge on this head. We have asserted that stays are detrimental to beauty of form; we shall now endeavor to show in what particulars.

The natural form of the part of the trunk which forms the waist is not absolutely cylindrical, but is flattened considerably in front and back, so that the breadth is much greater from side to side than from front to back. This was undoubtedly contrived for wise purposes; yet fashion, with its usual caprice, has interfered with nature, and by promulgating the pernicious error that a rounded form of the waist is more beautiful than the flattened form adopted by nature, has endeavored to effect this change by means of the stays, which force the lower ribs closer together, and so produce the desired form. Nothing can be more ungraceful than the sudden diminution in the size of the waist occasioned by the compression of the ribs, as compared with the gently undulating line of nature; yet, we are sorry to say, nothing is more common. A glance at the cuts, Figs. 43, 44, 45, 46, from the work of Sommæring, will explain our meaning more clearly than words. Fig. 43 represents the natural waist of the Venus of antiquity; Fig. 45, that of a lady of the modern period. The diagrams 44 and 46 show the structure of the ribs of each.

It will be seen that, by the pressure of the stays, the arch formed by the lower ribs is entirely closed, and the waist becomes four or five inches smaller than it was intended by nature. Is it any wonder that persons so deformed should have bad health, or that they should produce unhealthy offspring? Is it any wonder that so many young mothers should have to lament the loss of their first born? We have frequently traced tight lacing in connection with this sad event, and we cannot help looking upon it as cause and effect.

By way of further illustration, we refer our readers to some of the numerous engravings from statues in the Art Journal, which, though very beautiful, are not distinguished by small waists. We may mention, as examples, Bailey's “Graces;” Marshall's “Dancing Girl Reposing;” “The Toilet,” by Wickman; “The Bavaria,” by Schwanthaler; and “The Psyche,” by Theed.

There is another effect produced by tight lacing, which is too ungraceful in its results to be overlooked, namely, that a pressure on one part is frequently, from the elasticity of the figure, compensated by an enlargement in another part. It has been frequently urged by inconsiderate persons, that, where there is a tendency to corpulency, stays are necessary to limit exuberant growth, and confine the form within the limits of gentility. We believe that this is entirely a mistake, and that, if the waist be compressed, greater fulness will be perceptible both above and below, just as, when one ties a string tight round the middle of a pillow, it is rendered fuller at each end. With reference to the waist, as to every thing else, the juste milieu is literally the thing to be desired.

It has been already observed, that a small waist is beautiful only when it is accompanied by a slender and small figure; but, as the part of the trunk, immediately beneath the arms, is filled with powerful muscles, these, when developed by exercise, impart a breadth to this part of the figure which, by comparison, causes the waist to appear small. A familiar example of this, in the male figure, presents itself in the Hercules, the waist of which appears disproportionately small; yet it is really of the normal size, its apparent smallness being occasioned by the prodigious development of the muscles of the upper part of the body.

The true way of diminishing the apparent size of the waist, is, as we have remarked above, by increasing the power of the muscles of the upper part of the frame. This can only be done by exercise; and as the habits of society, as now constituted, preclude the employment of young ladies in household duties, they are obliged to find a substitute for this healthy exertion in calisthenics. There was a time when even the queens of Spain did not disdain to employ their royal hands in making sausages; and to such perfection was this culinary accomplishment carried at one period, that it is upon record that the Emperor Charles V., after his retirement from the cares and dignities of the empire, longed for sausages “of the kind which Queen Juaña, now in glory, used to pride herself in making in the Flemish fashion.” (See Mr. Stirling's “Cloister Life of Charles V.”) This is really like going back to the old times, when—

In England, some fifty years ago, the young ladies of the ancient city of Norwich were not considered to have completed their education, until they had spent some months under the tuition of the first confectioner in the city, in learning to make cakes and pastry—an art which they afterwards continued when they possessed houses of their own. This wholesome discipline of beating eggs and whipping creams, kneading biscuits and gingerbread, was calculated to preserve their health, and afford sufficient exercise to the muscles of the arms and shoulders, without having recourse to artificial modes of exertion.

It does not appear that the ancients set the same value upon a small waist as the moderns; for, in their draped female figures, the whole circuit of the waist is seldom visible, some folds of the drapery being suffered to fall over a part, thus leaving its exact extent to the imagination. The same remark is applicable to the great Italian painters, who seldom marked the whole contour of the waist, unless when painting portraits, in which case the costume was of course observed.

It was not so, however, with the shoulders, the true width of which was always seen; and how voluminous soever the folds of the drapery around the body, it was never arranged so as to add to the width of the shoulders. Narrow shoulders and broad hips are esteemed beauties in the female figure, while in the male figure the broad shoulders and narrow hips are most admired.

The costume of the modern Greeks is frequently very graceful, (Fig. 47, peasant from the environs of Athens,) and it adapts itself well to the figure, the movements of which it does not restrain. The prevailing characteristics of the costume are a long robe, reaching to the ground, with full sleeves, very wide at the bands. This dress is frequently embroidered with a graceful pattern round the skirt and sleeves. Over it is worn a pelisse, which reaches only to the knees, and is open in front; either without any sleeves, or with tight ones, finishing at the elbows; beneath which are seen the full sleeves of the long robe. The drapery over the bust is full, and is sometimes confined at the waist by a belt; at others it is suffered to hang loosely until it meets the broad, sash-like girdle which encircles the hips, and which hangs so loosely that the hands are rested in its folds as in a pocket.

The drapery generally terminates at the throat, under a necklace of coins or jewels. The most usual form of head-dress is a veil so voluminous as to cover the head and shoulders; one end of the veil is frequently thrown over the shoulder, or gathered into a knot behind. The shoes, apparently worn only for walking, consist generally of a very thick sole, with a cap over the toes.

One glance at the graceful figures in the plates is sufficient to show how unnecessary stays are to the beauty of the figure. Fig. 48, Shepherdess of Arcadia.

The modern Greek costumes which we have selected for our illustrations, from the beautiful work of M. de Stackelberg, (“Costumes et Peuples de la Grèce Moderne,” published at Rome, 1825,) suggest several points for consideration, and some for our imitation. The dress is long and flowing, and high in the neck. It does not add to the width of the shoulders; it conceals the exact size of the waist by the loose pelisse, which is open in front; it falls in a graceful and flowing line from the arm-pits, narrowing a little at the waist, and spreading gently over the hips, when the skirt falls by its own weight into large folds, instead of curving suddenly from an unnaturally small waist over a hideous bustle, and increasing in size downward to the hem of the dress, like a bell, as in the present English costume.

Figs. 42 and 49 are selected from the “Illustrated London News.” (Volume for 1851, July to December, pp. 20 and 117.) The one represents out-door costume, the other in-door. Many such are scattered through the pages of our amusing and valuable contemporary. For the out-door costume we beg to refer our readers to the large woodcut in the same volume, (pp. 424, 425.) If a traveller from a distant country, unacquainted with the English and French fashions, were to contemplate this cut, he would be puzzled to account for the remarkable shape of the ladies, who all, more or less, resemble the figure we have selected for our illustration; and, if he is any thing of a naturalist, he will set them down in his own mind as belonging to a new species of the genus homo. Looking at this and other prints of the day, we should think that the artists intended to convey a satire on the ladies' dress, if we did not frequently meet with such figures in real life.

The lady in the evening dress (Fig. 49) is from a large woodcut in the same journal representing a ball. This costume, with much pretension to elegance, exhibits most of the faults of the modern style of dress. It combines the indecently low dress, with the pinched waist, and the hoop petticoat. In the figure of the woman of Mitylene, (Fig. 50,) the true form and width of the shoulders are apparent, and the form of the bust is indicated, but not exposed, through the loosely fitting drapery which covers it. In the figure of the Athenian peasant, (Fig. 47,). the loose drapery over the bust is confined at the waist by a broad band, while the hips are encircled by the sash-like girdle in which the figure rests her hands. The skirt of the pelisse appears double, and the short sleeve, embroidered at the edge, shows the full sleeve of the under drapery, also richly embroidered. In the second figure from the environs of Athens, (Fig. 51,) we observe that the skirt of the pelisse, instead of being set on in gathers or plaits, as our dresses are, is “gored,” or sloped away at the top, where it unites almost imperceptibly with the body, giving rise to undulating lines, instead of sudden transitions and curves. In the cut of the Arcadian peasant, (Fig. 48,) the pelisse is shortened almost to a spencer, or côte hardie, and it wants the graceful flow of the longer skirt, for which the closely fitting embroidered apron is no compensation. This figure is useful in showing that tight bodies may be fitted to the figure without stays. The heavy rolled girdle on the hips is no improvement. The dress of the Algerine woman, (Fig. 53,) copied from the “Illustrated London News,” bears a strong resemblance to the Greek costume, and is very graceful. It is not deformed either by the pinched waist or the stays. In the tenth century, the French costume (Fig. 52) somewhat resembled that of the modern Greeks; the former, however, had not the short pelisse, but, in its place, the ladies wore a long veil, which covered the head, and reached nearly to the feet.

The Greek and Oriental costume has always been a favorite with painters: the “Vernon Gallery” furnishes us with two illustrations; and the excellent engravings of these subjects in the Art Journal enable us to compare the costumes of the two figures while at a distance from the originals. The graceful figure of “The Greek Girl,” (engraved in the Art Journal for 1850,) painted by Sir Charles Eastlake, is not compressed by stays, but is easy and natural. The white under-drapery is confined at the waist, which is short, by a broad girdle, which appears to encircle it more than once, and adds to the apparent length of the waist; the open jacket, without a collar, falls gracefully from the shoulders, and conceals the limits of the waist; every thing is easy, natural, and graceful. M. De Stackelberg's beautiful figure of the “Archon's Wife” (Fig. 54) shows the district whence Sir C. Eastlake drew his model. There is the same flowing hair,—from which hang carnations, as in the picture in the “Vernon Gallery,”—the same cap, the same necklace. But in the baron's figure, we find the waist encircled with a broad band, six or seven inches in width, while the lady rests her hand on the sash-like girdle, which falls round the hips.

Turn we now to Pickersgill's “Syrian Maid,” (engraved in the Art Journal for 1850:) here, we see, the artist has taken a painter's license, and represented the fair Oriental in stays, which, we believe, are happily unknown in the East. How stiff and constrained does this figure appear, after looking at Sir C. Eastlake's beautiful “Greek Girl;” how unnatural the form of the chest! The limits of the waist are not visible, it is true, in the “Syrian Maid,” but the shadow is so arranged, that the rounded form, to which we have before alluded, and which fashion deems necessary, is plainly perceptible; and an impression is made that the waist is small and pinched.

We could mention some cases in which the girdle is omitted altogether, without any detriment to the gracefulness of the figure. Such dresses, however, though illustrative of the principle, are not adapted to the costume of real life. In sculpture, however, they frequently occur. We may mention Gibson's statue of her majesty, the female figure in M'Dougall's “Triumph of Love,” and “Penelope,” by Wyatt, which are engraved in the Art Journal, (the first in the year 1846, the others in 1849.) But the drapery of statues can, however, scarcely be taken as a precedent for that of the living subject, and although we mention that the girdle is sometimes dispensed with, we are far from advocating this in practice; nay, we consider the sash or girdle is indispensable; all that we stipulate for is, that it should not be so tight as to compress the figure, or impede circulation.

In concluding our remarks on this subject, we would observe, that the best means of improving the figure are to secure freedom of motion by the use of light and roomy clothing, and to strengthen the muscles by exercise. We may also observe, that singing is not only beneficial to the lungs, but that it strengthens the muscles, and increases the size of the chest, and, consequently, makes the waist appear smaller. Singing, and other suitable exercises in which both arms are used equally, will improve the figure more than all the backboards in the world.

CHAPTER III.

THE HEAD.

There is no part of the body which has been more exposed to the vicissitudes of fashion than the head, both as regards its natural covering of hair, and the artificial covering of caps and bonnets. At one time, we read of sprinkling the hair with gold dust; at another time, the bright brown hair, of the color of the horse-chestnut, so common in Italian pictures, was the fashion. This color, as well as that beautiful light golden tint sometimes seen in Italian pictures of the same period, was frequently the result of art, and receipts for producing both tints are still to be found in old books of “secreti.” Both these were in their turn discarded, and after a time the real color of the hair was lost in powder and pomatum. The improving taste of the present generation is, perhaps, nowhere more conspicuous than in permitting us to preserve the natural color of the hair, and to wear our own, whether it be black, brown, or gray. There is also a marked improvement in the more natural way in which the hair has been arranged during the last thirty years. We allude, particularly, to its being suffered to retain the direction intended by nature, instead of being combed upright, and turned over a cushion a foot or two in height.

These head-dresses, emphatically called, from their French origin, têtes, were built or plastered up only once a month: it is easy to imagine what a state they must have been in during the latter part of the time. Madame D'Oberkirch gives, in her Memoirs, an amusing description of a novel head-dress of this kind. We transcribe it for the amusement of our readers.

“This blessed 6th of June she awakened me at the earliest dawn. I was to get my hair dressed, and make a grand toilette, in order to go to Versailles, whither the queen had invited the Countess du Nord, for whose amusement a comedy was to be performed. These Court toilettes are never-ending, and this road from Paris to Versailles very fatiguing, especially where one is in continual fear of rumpling her petticoats and flounces. I tried that day, for the first time, a new fashion—one, too, which was not a little gênante. I wore in my hair little flat bottles, shaped to the curvature of the head; into these a little water was poured, for the purpose of preserving the freshness of the natural flowers worn in the hair, and of which the stems were immersed in the liquid. This did not always succeed, but when it did, the effect was charming. Nothing could be more lovely than the floral wreath crowning the snowy pyramid of powdered hair!” Few of our readers, we reckon, are inclined to participate in the admiration of the baroness, so fancifully expressed, for this singular head-dress.

We do not presume to enter into the question whether short curls are more becoming than long ones, or whether bands are preferable to curls of any kind; because, as the hair of some persons curls naturally, while that of others is quite straight, we consider that this is one of the points which must be decided accordingly as one style or the other is found to be most suitable to the individual. The principle in the arrangement of the hair round the forehead should be to preserve or assist the oval form of the face: as this differs in different individuals, the treatment should be adapted accordingly.

The arrangement of the long hair at the back of the head is a matter of taste; as it interferes but little with the countenance, it may be referred to the dictates of fashion; although in this, as in every thing else, simplicity in the arrangement, and grace in the direction of the lines, are the chief points to be considered. One of the most elegant head-dresses we remember to have seen, is that worn by the peasants of the Milanese and Ticinese. They have almost uniformly glossy, black hair, which is carried round the back of the head in a wide braid, in which are placed, at regular intervals, long silver pins, with large heads, which produce the effect of a coronet, and contrast well with the dark color of the hair.

The examples afforded by modern sculpture are not very instructive, inasmuch as the features selected by the sculptors are almost exclusively Greek, whereas the variety in nature is infinite. With the Greek features has also been adopted the antique style of arranging the hair, which is beautifully simple; that is to say, it is parted in the front, and falling down towards each temple, while the long ends rolled lightly back from the face so as to show the line which separates the hair from the forehead, or rather where it seems, as it were, to blend with the flesh tints—an arrangement which assists in preserving the oval contour of the face, are passed over the top of the ear, and looped into the fillet which binds the head. The very becoming arrangement of the hair in the engraving, from a portrait by Parmegianino, (Fig. 55,) is an adaptation of the antique style, and is remarkable for its simplicity and grace. Not less graceful, although more ornamental, is the arrangement of the hair in the beautiful figure called “Titian's Daughter.” Fig. 56. In both these instances, we observe the line—if line it may be called—where the color of the hair blends so harmoniously with the delicate tints of the forehead. The same arrangement of the hair round the face may be traced in the pictures by Murillo, and other great masters.

Sir Joshua Reynolds has frequently evinced consummate skill in the arrangement of the hair, so as to show the line which divides it from the forehead. For some interesting remarks on this subject, we refer our readers to an “Essay on Dress,” republished by Mr. Murray from the “Quarterly Review.” Nothing can be more graceful than Sir Joshua's mode of disposing of the hair when he was able to follow the dictates of his own good taste; and he deserves great credit for the skill with which he frequently treated the enormous head-dresses which in his time disfigured the heads of our countrywomen. The charming figure of Lady Harrington (Fig. 57) would have been perfect without the superstructure on her beautiful head. How stiff is the head-dress of the next figure, (Fig. 58,) also, after Sir Joshua, when compared with the preceding.

The graceful Spanish mantilla, to which we can only allude, is too elegant to be overlooked: the modification of it, which of late years has been introduced into this country, is to be considered rather as an ornament than as a head-covering. It has been recently superseded by the long bows of ribbon worn at the back of the head—a costume borrowed from the Roman peasants. Fig. 59. The fashion for young people to cover the hair with a silken net, which, some centuries ago, was prevalent both in England and in France, has been again revived. Some of the more recent of these nets are very elegant in form.

The hats and bonnets have, during the last few years, been so moderate in size, and generally so graceful in form, that we will not criticize them more particularly. It will be sufficient to observe that, let the brim be what shape it will, the crown should be nearly of the form and size of the head. If this principle were always kept in view, as it should be, we should never again see the monster hats and bonnets which, some years ago, and even in the memory of persons now living, caricatured the lovely forms of our countrywomen.

CHAPTER IV.

THE DRESS.

We shall consider the dress, by which we mean, simply, the upper garment worn within doors, as consisting of three parts—the sleeve, the body, and the skirt.

The sleeve has changed its form as frequently as any part of our habiliments: sometimes it reached to the wrist, sometimes to a short distance below the shoulder. Sometimes it was tight to the arm; sometimes it fell in voluminous folds to the hands; now it was widest at the top, then widest at the bottom. To large sleeves themselves there is no objection, in a pictorial point of view, provided that their point of junction with the shoulder is so conspicuous that they do not add to the apparent width of the body in this part. The lines of the sleeves should be flowing; and they are much more graceful when they are widest in the lower part, especially when so open as to display to advantage the beautiful form of the wrist and fore-arm. In this way, they partake of the pyramid, while the inelegant gigot sleeve, which for so long a period enjoyed the favor of the ladies, presents the form of a cone reverted, and is obviously out of place in the human figure. When the large sleeve, supported by canes or whalebones, forms a continuous line with the shoulder, it gives an unnatural width to this part of the figure—an effect that is increased by the large collar which conceals the point where the sleeve meets the dress. Examples of the large, open sleeve, in its extreme character, may be studied with most advantage in the portraits of Vandyck. Fig. 60, Lady Lucy Percy, after Vandyck. The effect of these sleeves is frequently improved by their being lined with a different color, and sometimes by contrasting the rich silk of the outer sleeve with the thin gauze or lace which forms the immediate covering of the arm. The figures in the plates will show the comparative gracefulness of two kinds of large sleeves, namely, that which is widest at the top, and that which is widest below. If the outline of the central figure of our more modern group, (Fig. 61,)—consisting of three figures, which is copied from a French work,—were filled up with black, a person ignorant of the fashion might, from the great width of the shoulders, have mistaken it for the Farnese Hercules in petticoats.

The large sleeves, tight in the upper part, and enlarging gradually to the wrist, which are worn by the modern Greeks, are extremely graceful. When these are confined below the elbow, which is sometimes done for convenience, they resemble somewhat the elbow sleeves with wide ruffles which were so common in the time of Sir Joshua Reynolds. Sleeves like those now worn in Greece were fashionable in France in the tenth century, and again about the beginning of the sixteenth century. They were also worn by Jeanne d'Albret, the mother of Henry IV., and are seen in Fig. 41.

A very elegant sleeve, fitting nearly close at the shoulder, and becoming very full and long till it falls in graceful folds almost to the feet, prevailed in England during the time of Henry V. and VI. Fig. 62, copied from a manuscript of the time of Henry V., now preserved in the British Museum. On the authority of Professor Heideloff, it is said to have existed also in Flanders in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and in France in the fifteenth century. In the examples of continental costume, the tout ensemble is graceful, and especially the head-dress; while in England the elegant sleeve is accompanied with very short waists, and with the hideous, horned head-dresses then fashionable. The effect of these sleeves much resembles that of the mantles of the present day, and from its wide flow is only adapted for full dress, or out-of-door costume. The sleeves worn under these full ones were generally tight. At a much later period, the large sleeves were made of more moderate dimensions, both in length and width, and a full sleeve of fine lawn or muslin, fastened at the wrist with a band, and edged with a lace ruffle, was worn beneath. This kind of sleeve has recently been again introduced into England, but has given place to another form, in which the under sleeve of lace or muslin, being of the same size as the upper, suffers the lower part of the arm to be visible. The effect of this sleeve, which is certainly becoming to a finely-formed arm, is analogous to that of the elbow sleeve, which, with its deep ruffles of point lace, is frequent on the portraits of Sir Joshua Reynolds.

The slashed sleeve, criticized by Shakspeare in the “Taming of the Shrew,” was sometimes very elegant. The form in which it appears in Fig. 63, worn in the fifteenth century, is particularly graceful. Not so, however, the lower part of the sleeve.

In the preceding remarks, we have considered the sleeve merely in a picturesque point of view, without reference to its convenience or inconvenience.

The length of the waist has always been a matter of caprice. Sometimes the girdle was placed nearly under the arms; sometimes it passed to the opposite extreme, and was suffered to fall upon the hips. Sometimes it was drawn tightly round the middle, when it seemed to cut the body almost in two, like an hourglass. Judging from what we see, we should say that this is a feat which many ladies of the present time are endeavoring to achieve. The first and third cases are almost equally objectionable, because they distort the figure. The hip girdle, which is common in Greece (as shown in Figs. 48 and 53) and Oriental countries, prevailed also in England and France some centuries ago. The miniatures of old manuscripts furnish us with examples of long-waisted dresses fitting closely to the person, sometimes stiffened like the modern stays, at others yielding to the figure. The waist of this kind of dress reached to the hips, where it was joined to the full petticoat, which was gathered round the top—an extremely ungraceful fashion. The hip girdle, properly used, is, however, by no means inelegant. It is not at all necessary that it should coincide with the waist of the dress; it should be merely looped or clasped loosely round the figure, and suffered to fall to its place by its own weight. But to enable it to do so in a graceful manner, it is essential that the skirt of the dress should be so united with the body as to produce no harsh lines of separation, or sudden changes of curvature; as, for example, when the skirt is set on in full plaits, or gathers, and spread over a hoop. We have before noticed, that this point was attended to by Rubens, (Fig. 66,) by Vandyck, (Fig. 65,) by Sir Joshua Reynolds, and by the modern Greeks. We refer also to the elegant figure 64. The most natural situation for the girdle, or point of junction of the body with the skirt, is somewhere between the end of the breast bone and the last rib, as seen in front—a space of about three or four inches. Fashion may dictate the exact spot, but within this space it cannot be positively wrong. The effect is good when the whole space is filled with a wide sash folded round the waist, as in Sir C. Eastlake's “Greek Girl,” or some of the graceful portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds. How much more elegant is a sash of this description than the stiff line which characterizes the upper part of the dress of “Sancta Victoria.” (Fig. 64.) The whalebone, or busk, is absolutely necessary to keep the dress in its proper place. The resemblance in form between the body of the dress of this figure and those now or recently in fashion cannot fail to arrest the attention of the reader. Stiff, though, as it undoubtedly is, the whole dress is superior to the modern in the general flow of the lines uniting the body and skirt. Long skirts are more graceful than short ones, and a train of moderate length adds to the elegance of a dress, but not to its convenience. Long dresses, also, add to the apparent height of a figure, and for this reason they are well adapted to short persons. For the same reason, waists of moderate length are more generally becoming than those that are very long, because the latter, by shortening the skirt of the dress, diminish the apparent height.

Besides the variation in length, the skirts of dresses have passed through every gradation of fulness. At one time, it was the fashion to slope gradually from the waist, without gathers or plaits; then a little fulness was admitted at the back; then a little at the front, also. The next step was to carry the fulness all round the waist. In the graceful costume of the time of Vandyck, and even in the more stiff and formal dress delineated in the pictures of Rubens, the skirt was united to the body by large, flat plaits, when the fulness expanded gradually and gracefully, and the rich material of the dress spread in well-arranged folds to the feet. The lines were gently undulating and graceful, and that unnatural and clumsy contrivance called a “bustle”—a near relation of the hoop and fardingale—was at that time happily unknown. This principle of uniting the skirt gradually with the body of the dress is carried out to the fullest extent by the modern Greeks. In the figure of the peasant from the neighborhood of Athens, (Fig. 47,) the pelisse is made without gathers or plaits: the skirt, which hangs full round the knees, is “gored” or sloped away till it fits the body at the waist. The long underskirt is, as we find from the figure of the woman of Makrinitza, (Fig. 67,) gathered several times, so as to lie flat to the figure, instead of being spread over the inelegant “bustle.” It is only necessary to compare these graceful figures, in which due regard has been paid to the undulating lines of the figure, with a fashionable lady of the present day, whose “polka jacket,” or whatever may be the name of this article of dress, is cut with violent and deep curves, to enable it to spread itself over the bustle and prominent folds of the dress.

Not satisfied with the bustle in the upper part of the skirt, some ladies of the present day have returned to the old practice of wearing hoops, to make the dresses stand out at the base. These are easily recognized in the street by the “swagging”—no other term will exactly convey the idea—from side to side of the hoops, an effect which is distinctly visible as the wearer walks along. It is difficult to imagine what there is so attractive in the fardingale and hoop, that they should have prevailed, in some form or other, for so many years, and that they should have maintained their ground in spite of the cutting, though playful, raillery of the “Spectator,” and the jeers and caricatures of less refined censors of the eccentricities of dress. They were not recommended either by beauty of line or convenience, but by the tyrant Fashion, and we owe some gratitude to George IV., who banished the last relics of this singular fashion from the court dress, of which, until his time, it continued to form a part. Who could imagine that there would be an attempt to revive the hoop petticoat in the nineteenth century? We invite our readers to contrast the lines of the drapery in the figures after Vandyck, (Figs. 60 and 61,) and those in the modern Greek costume, (Figs. 51 and 54,) with that of a lady in a hoop, after a satirical painter, Hogarth, (Fig. 68,) and two figures from a design by Jules David, in “Le Moniteur de la Mode,” a modern fashionable authority in dress. (Figs. 69 and 70.) There can be no doubt which is the most graceful. The width of the shoulders and the tight waist of the latter, will not escape the notice of our readers.

CHAPTER V.

THE FEET.

The same bad taste which insists upon a small waist, let the height and proportions of the figure be what they will, decrees that a small foot is essential to beauty.