Mina and I hauled her up by the arms into the

boat.—Page 22.

Mina and I hauled her up by the arms into the

boat.—Page 22.

Project Gutenberg's What Happened to Inger Johanne, by Dikken Zwilgmeyer

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: What Happened to Inger Johanne

As Told by Herself

Author: Dikken Zwilgmeyer

Illustrator: Florence Liley Young

Translator: Emilie Poulsson

Release Date: May 23, 2010 [EBook #32502]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WHAT HAPPENED TO INGER JOHANNE ***

Produced by Suzanne Shell, Josephine Paolucci and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net.

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Mina and I hauled her up by the arms into the

boat.—Page 22.

Mina and I hauled her up by the arms into the

boat.—Page 22.

Published, October, 1919

Copyright, 1919,

By Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Co.

All Rights Reserved

What Happened to Inger Johanne

Norwood Press

BERWICK & SMITH CO.

Norwood, Mass.

U. S. A.

CHAPTER PAGE

I, Inger Johanne 11

I. Ourselves, Our Town, and Other Things 13

II. An Interrupted Celebration 31

III. My First Journey Alone 41

IV. What Happened One St. John's Day 59

V. Left Behind 70

VI. In the Meal Chest 86

VII. Pets: Particularly Carola-Carolus 93

VIII. Christmas Mumming 113

IX. Mother Brita's Grandchild 123

X. The Mason's Little Pigs 143

XI. Locked In 156

XII. At Goodfields 170

XIII. Oleana's Clock 179

XIV. A Trip to Goodfields Saeter 186

XV. Lost in the Forest 204

XVI. Traveling with a Billy-Goat 223

XVII. In School 239

XVIII. When the Circus Came 253

XIX. Moving 273

Mina and I hauled her up by the arms into

the boat (page 22) Frontispiece

FACING PAGE

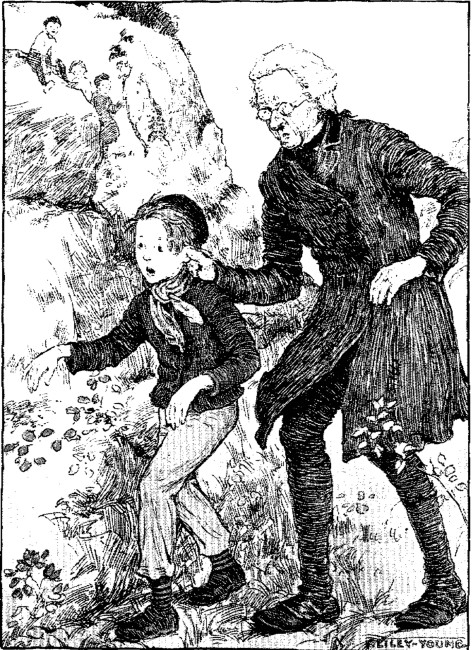

The dean took Peter by the left ear and dragged him away 40

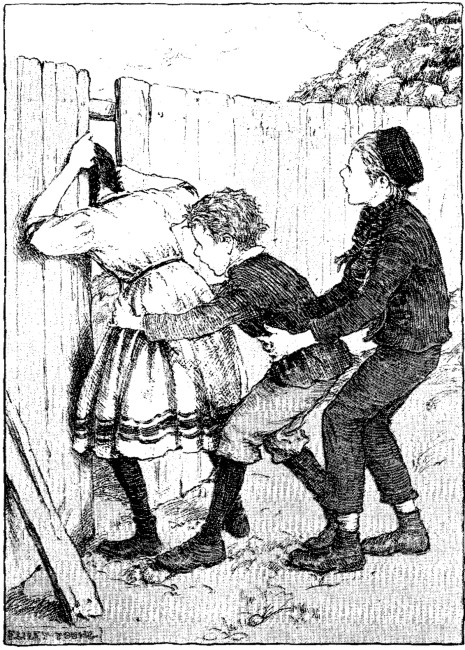

They just hauled and pulled me as hard as they could 68

She told me the whole story of her life 80

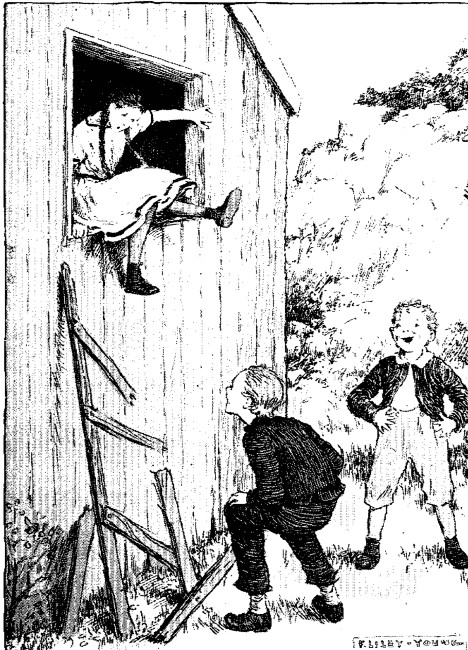

And how Karsten and Peter laughed down below! 110

The only pleasant thing was that there came a

tremendously big heavy snowslide right

down on the little shoemaker 124

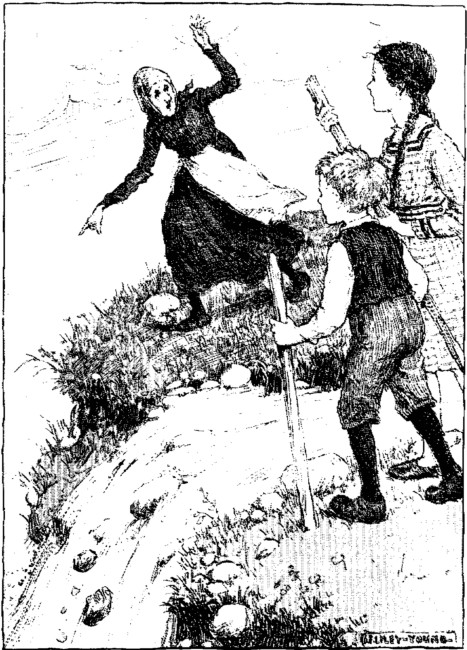

She began to shriek and point and throw up her arms 152

And smashed a window-pane with it 166

"Oleana," said I, "we wanted to give you a clock" 184

How we wandered,—round and round, up and down, hither and thither! 208

The beautiful red cherries crackled in Billy-goat's mouth 236

I stood on the barn steps with a long whip 260

I have always heard grown people say that when you meet strangers and there is no one else to introduce you, it is highly proper and polite to introduce yourself. Uncle Karl says that polite people always get on in the world; and as I want dreadfully to do that, I will be polite and tell you who I am.

Everybody in our town knows me; and they call me "the Judge's Inger Johanne," because my father is the town judge, you see; and I am thirteen years old. So now you know me.

And just think! I am going to write a book! If you ask, "What about?" I shall have to[Pg 12] say, "Nothing in particular," for I haven't a speck more to tell of than other girls thirteen years old have, except that queer things are always happening to me, somehow.

Probably it isn't easy to write a book when you have never done it before, especially when thoughts come galloping through your head as fast as they do through mine. Why, I think of a hundred things, while Peter, the dean's son, is thinking of one and a half! But, easy or not, since I, Inger Johanne, have set my heart on writing a book, write it I will, you may be sure; and now I begin in earnest.

There are four brothers and sisters of us at home, and as I am the eldest, it is natural that I should describe myself first. I am very tall and slim (Mother calls it "long and lanky"); and, sad to say, I have very large hands and very large feet. "My, what big feet!" our horrid old shoemaker always says when he measures me for a pair of new shoes. I feel like punching his tousled head for him as he kneels there taking my measure; for he has said that so often now that I am sick and tired of it.

My hair is in two long brown braids down[Pg 14] my back. That is well enough, but my nose is too broad, I think; so sometimes when I sit and study I put a doll's clothespin on it to make it smaller; but when I take the clothespin off, my nose springs right out again; so there is no help for it, probably.

Why people say such a thing is a puzzle; but they all, especially the boys, do say that I am so self-important. I say I am not—not in the least—and I must surely know best about myself, now that I am as old as I am. But I ask you girls whether it is pleasant to have boys pull your braids, or call you "Ginger," or to have them stand and whistle and give cat-calls down by the garden wall, when they want you to come out. I have said that they must once for all understand that my braids must be let alone, that I will not be whistled for in that manner, and that I will come out when I am ready and not before. And then they call me self-important!

After me comes Karsten. He has a large, fair face, light hair, and big sticking-out ears.[Pg 15] It is a shame to tease any one, but I do love to tease Karsten, for he gets so excited that he flushes scarlet out to the tips of his ears and looks awfully funny! Then he runs after me—which is, of course, just what I want—and if he catches me, gives me one or two good whacks; but usually we are the best of friends. Karsten likes to talk about wonderfully strong men and how much they can lift on their little finger with their arm stretched out; and he is great at exaggeration. People say I exaggerate and add a sauce to everything, but they ought to hear Karsten! Anyway, I don't exaggerate,—I only have a lively imagination.

After Karsten there is a skip of five years; then comes Olaug, who is still so little that she goes to a "baby school" to learn her letters, and the Catechism. I often go to fetch Olaug home, for it is awfully funny there. When Miss Einarsen, the teacher, and her sister say anything they do not wish the children to understand, they use P-speech: Can-pan you-pou talk-palk it-pit? I went there often on purpose[Pg 16] to learn it, for it is so ignorant to know only one language. But now I know both Norwegian and P-speech. Olaug always remembers exactly the days when the school money is to be paid, for on those days each child who brings the money gets a lump of brown sugar. Once a year the minister comes to Miss Einarsen's to catechize the children; but Miss Einarsen always stands behind the one who is being questioned and whispers the right answer. "Oh, Teacher is telling, Teacher is telling!" the children say to each other. "Yes, I am telling," says Miss Einarsen. "How do you think you would get along if I didn't?" On examination days Miss Einarsen always treats to thin chocolate in tiny cups, and the children drink about six cups apiece! Well, that's how it is at Olaug's school.

After Olaug comes Karl, but he is only a little midget. He thinks he can reach the moon if he stands on a chair by the window and stretches his arms away up high. He is perfectly wild to get hold of the moon because he[Pg 17] thinks it would roll about so beautifully on the floor.

We live in a little town on the sea-coast. It is much more fun to live in a little town than a big one, for then you know every one of the boys and girls, and there are many more good places to play in; and all the sea besides. Oh, yes! I know very well that there are lots of small towns that do not lie by the sea. They must be horrid!

Think how we have the great ocean thundering in against the shore, wave after wave. Oh, it is delightful! Any one who has not seen that has missed a really beautiful sight. It is beautiful both in summer and winter; but I do believe it is most beautiful and wonderful in the time of the autumn storms. Go up on the hilltop some day in autumn, where the big beacon is, and look out over the sea! You have to hold on to your hat, hold on to your clothes, hold on to your body itself, almost. Whew-ew! the[Pg 18] wind! How it blows! How it blows! And the whole ocean looks as if it were astir from the very bottom. Big black billows with broad white crests of foam come rolling, rolling, rolling in—one wave does not wait for the other. And how they break over the islands out where the lighthouse is! The lighthouse stands like a tall white ghost against the dark sea and the dark sky;—sinks behind an enormous wave, rises again, sinks and rises again. How swiftly the clouds fly! How the ocean seethes and roars! We hear it all over town, sobbing, roaring, thundering! Away in by the wharves of the market square the waters are all in a turmoil. The little boats rock and rock, and the big ships dip up and down. The wet rigging sparkles, the mooring chains strain and creak, and there is such a smell of salt in the air! You can almost taste the salt with your tongue.

In such weather the damaged ships come in. One autumn there came a Spanish steamship, with a green funnel and a white hull. It lay with almost its whole stern under water when[Pg 19] the pilot from Krabbesund brought it in. That was jolly; not for the people on board,—it was anything but jolly for them,—but for us children.

When we choose, we go out into the harbor in boats and row round and round among the strange ships. At last, very likely, the sailors call out to us and ask us to come on board, and then it doesn't take us long to scramble up the ladder, you may be sure! On board, it is awfully jolly. Once a French skipper gave us some pineapple preserves; but generally we only get crackers. When the Spanish ship was in, the streets swarmed with foreign sailors, with long brown necks and burning black eyes. Then the old policeman, Mr. Weiby, strutted about, and sent Father long written reports about street rows and disturbances. The Spaniards didn't bother themselves a mite about old Weiby, puffing around with his chin high in the air!

Sometimes on summer afternoons when the water lies calm and shining, we slip off and[Pg 20] borrow a boat (Mr. Terkelsen's, quite often) and go rowing around the island. Then, afterwards, we float about,—dabbling and splashing in the darkened water until evening comes on. Ah! that is pleasure!

One summer evening Massa Peckell, Mina Trap and I saved two people from drowning; and we were praised for it in the newspapers. Really it is most delightful to see your name in print! I should like ever so much to do something else that the papers would praise me for, but I don't know what it could be!

This is how it happened that time. We had borrowed old Terkelsen's boat and rowed quite a way out. From a wharf on one of the islands another boat laden with wood came towards us. The wood was in slabs and chips and was piled high fore and aft. Down between the piles sat two children rowing. As they came nearer we saw that it was Lisa and George, the lighthouse-keeper's children. Mina and I were rowing,[Pg 21] but I was so much stronger that I kept rowing her round and round, so that we were laughing and having a jolly time. Probably George and Lisa were watching us and forgetting all about their top-heavy boat; for, the next thing we knew, both piles of wood, George and Lisa, and the boat were all upset in the water. It was a dreadful thing to see!

"We—we'll go ashore and get help!" shrieked Massa. Humph! A pretty time they would have if we did that! Mina and I had more sense, so we turned our boat quickly and were over to the spot in two or three strokes of the oars. The boat was completely capsized and the chips floated over the water as thick as a floor. But George and Lisa were nowhere to be seen!

Then you may believe that Mina and I yelled with all our might! You know how it sounds over the water. My! how we did shriek! It must have been heard all over town. I saw people away back on the wharves running to the water to see what was the matter.[Pg 22]

Then, there bobbed Lisa's head up among the chips, and Mina and I hauled her up by the arms into the boat. Massa had to hang away over on the starboard so that our boat shouldn't upset, too. Old Terkelsen is always so mad when we take his boat without leave. I can't imagine, for the life of me, why he should get so provoked over it. We always bring it back just as good as ever! Massa and Mina and I have no desire, forsooth, to set out to sea through the Skagerak and sail away with it! But on that day it was fortunate that we had taken his boat, and not some miserable little thing belonging to anybody else.

As soon as Lisa got her breath, she cried out: "Oh! the chips! the chips!" But just then George's head appeared, and Mina and I made a grab for him; but he was so stupidly heavy that we couldn't pull him in; so we only held him fast and screamed and screamed. Out from the wharves and from the islands came ever so many boats and lots of people. Those minutes that we hung over the edge of that[Pg 23] boat and held on with all our might to the half-drowned George, who was as heavy as lead—shall I ever forget? George was drawn up into another boat and they took us in tow. Lisa sat like a drowned rat and cried till she choked. Then Massa began to cry, too;—and so we came to the wharf.

For several days after the rescue I couldn't go into the street without people's stopping me and wanting a full account of how it all happened. Really, it is quite troublesome to be famous; but I like it pretty well, nevertheless.

When Mina and I met that stout, lighthouse-Lisa on the street next time, we couldn't imagine how we had ever been able to drag her into the boat! But you mustn't expect gratitude in this world. Many a time since then has Lisa come tiptoeing along after us on the street, tossing her head this way and that, mimicking us, to show how self-important we are! And that after we saved the stupid creature from drowning![Pg 24]

We live up on a hill in a lovely old house. People call it an old rattletrap of a house, but that is nothing but envy because they don't live there themselves. There are big old elm-trees around the house which shade it and make the back part of the deep rooms quite dark. The rafters show overhead, and the floors rock up and down when you walk hard on them, just because they are so old. There is one place in the parlor floor where it rocks especially. When no one is in there except Karsten and myself, we often tramp with all our might where the floor rocks most, for we want dreadfully to see whether we can't break through into the cellar.

There are several gardens belonging to our house. One big garden has only plum-trees with slender trunks and a little cluster of branches and leaves high, high up. When I walk down there under the plum-trees, I often imagine that I am down in the tropics, wandering under palm-trees. I have a garden of my[Pg 25] own, too. I wouldn't have mentioned it particularly if there weren't one remarkable fact about it. Really and truly, nothing will grow in it but that dark blue toad-flax—you know what that is. Every single spring I buy seeds with my pocket money, and plant and water and take care of them, but when summer comes there is nothing in the garden but great big toad-flax stalks all gone to seed. It is awfully tiresome, especially when they have such a horrid name.

Now I think it is time to describe all of us boys and girls who play together, and whom I am going to tell about in my book.

There is Peter, the dean's son, with his sleepy brown eyes and freckles as big as barleycorns. Peter is a cowardly chap. He never has any opinion of his own. And if he had one he would never dare to stand by it if you contradicted him. He's terribly afraid of the cold, too, and goes about with a scarf wound around his neck, and mittens if a single snowflake falls.[Pg 26] Still, Peter is very nice indeed; he does everything that I want him to.

Then there is my brother Karsten, but I've told you about him. He is a little younger than the rest of us.

Another boy is Ezekiel Weiby. He is fourteen years old and has an awfully narrow face—not much broader than a ruler. He is very clever and reads every sort of book. But when he is out with the rest of us, he wants us all to sit still and hear him tell about everything he has been reading. For a while that is very pleasant, but I get tired of it pretty soon, for I hate to sit still long at a time. That is a very funny thing. Other people get tired of walking or running about, but I can't stand it to sit still.

Nils Trap is the bravest of all the boys. He never wears an overcoat, but goes around with his hands in his pockets whistling a funny tune:

which you probably don't know. Nils Trap clambers like a cat up in the rigging of the[Pg 27] vessels. Some people say that they have seen him lie out straight on the ball at the top of the big mast of the Palmerston and spin himself round. But others say that is a whopper, for the Palmerston is the biggest ship in town with the very highest masts. Perhaps he could lie and balance himself on top of it, but spin himself round! That he couldn't do if he tried till he was blue in the face.

Then there are Massa, and Mina, and I. Mina is Nils's sister and my best friend. She has a gold filling in one of her front teeth. Oh, if I could only have such a shining little spot as that in my teeth! Mine are only plain straight white ones and they look really dull beside hers.

Massa Peckell is plump and easy-going. She thinks the most beautiful thing is to be pale and thin. She heard that it would give you a delicate pale skin if you drank vinegar and ate rice soup, so she tried it as hard as she could. But her beauty-cure only gave her the stomach-ache. Her fat, red cheeks are just like Baldwin apples still.[Pg 28]

Every day, summer and winter, we are together, all of us that I have written about here. In summer there is a lot of fun to be had everywhere, but especially on the delightful hill back of our house—(I will tell you all about that hill some other time),—but in winter, humph! What can girls and boys do in such horrid mild winters as we are now having, I should really like to know! Last year we had no snow to speak of, and here it is now after New Year's and I haven't yet, to my recollection, seen a single snowflake which didn't melt in five minutes, or any ice that didn't break through as soon as you stamped your heel on it. If I could only make a journey to the North Pole and do what I wanted to there, I should send down some lovely soft snow-drifts and some smooth blue glistening ice in a jiffy, to all the boys and girls who are wishing for them day after day.

In the meantime I am glad that I have begun to write this book in winter, otherwise I should be bored to death.

Of course we go out-of-doors now too, even[Pg 29] though the mild weather is disgusting; but when it storms as hard as it did in the autumn, making the old elm-trees crash and swish so that we can scarcely hear ourselves talk, then it is not comfortable to play out-of-doors, I assure you. At such times we often shut ourselves up in the little room over the wood-shed. There is nothing up there but a keg of red ochre which we paint ourselves with, but really we have lots of fun there, nevertheless.

Ezekiel always seizes the chance to give a lecture in the wood-shed, and his words gush out like water from a fountain. When I get tired of it, I sneak around behind him and give him a little English punch in the back, for I am very clever at boxing, you must know. "Come on! Can you use your fists like an Englishman?" And then I roll my hands round very fast, just as I have seen the English sailors do, and give him a quick punch in the stomach with my fist.

Ezekiel squirms about like a worm, and defends himself with his small weak fingers. The[Pg 30] others laugh, and Ezekiel and I laugh with them, and so we all laugh together.

Well, now you know us all, and you know what it is like around here.

My, how well I remember the day that we almost killed the dean's wife! That sounds queer; but it really was a live dean's wife that we really came within a hair's breadth of killing. And that, while we were just playing and celebrating the Seventeenth of May—the day when Norway adopted her own constitution, you know.

Now you shall hear how it happened.

Right behind our old house we have a whole big breezy hill. If any of you live down on the coast, you will know how beautiful it is and what fun one can have up on such a hill. If you have only seen it as you went by on the steamer, you would never imagine how lovely it is up on bare gray hills that look out towards the sea. Little soil, but lots of sunshine; wherever there is a tiny crevice, fine long blades of[Pg 32] grass, buttercups, and yellow broom will immediately start up. Wild rose bushes and juniper cling to the hillside here and there, and then the heather away up on the top;—all over the whole flat top nothing but purple heather. Above is the clear blue sky; and out there the sea in a great wide circle—nothing to shut off the view; oh, it is glorious!

This has really nothing to do with the dean's wife, but I only wanted to explain what it was like up there on the hill. For it was up there that Nils Trap, Ezekiel, Peter, Karsten, Mina, Massa, and I played, many a pleasant day.

Right at our yard the hill begins to be steeper; first comes a little walled-in garden, then terraces and cliffs, big rocks and little rocks, then down a steep precipice, and then up a few steps again where you have to use hands and feet both, and grab hold of the heather and juniper if you want to go farther up.

About half-way up the hill there is a great big rock jutting out, which you can only climb on one side, and that with the greatest difficulty.[Pg 33] This is our fort. Here we have both batteries and bastions, a room for bullets and cannon-balls, a room for powder, and a dungeon. From up there we have the most splendid view down over the town with its low gaily painted wooden houses, and the small leafy linden-trees that creep up through the streets. From our fort people down there look just like darning-needles; from the very top of the hill they look like a swarming mass of little pins.

I remember distinctly that particular Seventeenth of May; the spring had come so early that we already had fine young birch leaves and clear mild air. For several days we had been talking about a feast that we wanted to have in the dungeon, for there we should be wholly out of sight. There was to be a salute, speeches and songs. Peter and Karsten were always the gunners. With much trouble we had carried big stones up to the fort; these we threw with all our might down again over the precipice. This was our way of giving a salute; it made no little racket, you may be sure! The boys were[Pg 34] to provide something to drink, and we the cake and glasses. We were never allowed to take any glasses up on the hill, except old goblets with the feet broken off. I thought then it was terribly stingy of Mother not to let us have proper glasses.

Ezekiel made the speech in honor of the day. I can still see his thin white fingers round the broken glass while he spouted and speechified about "our young freedom crowns this day of liberty with flowers." I had lately read the whole speech in an old children's paper, and of course had to confide this fact to Mina; the others wanted to know what we were laughing about, and at last all the listeners were laughing and whispering to each other; but Ezekiel stuck to it. After the speech four stones were thrown down. Karsten was beaming. "Oh, oh, what a crash!" he kept saying.

After that Ezekiel made a speech in honor of Sweden; at the end of the speech he suggested that we should sing:

but as none of us knew the tune, and Ezekiel himself hadn't a speck of music in him, the song wouldn't go. For it didn't help us at all for him to insist that he heard the tune plainly in his head. Then Nils Trap made a speech in honor of the ladies; I remember how I admired the few telling words: "A cheer and four shots for the ladies!" Not a bit more! I thought that sounded so awfully manlike.

Peter rushed off to the top of the fort to fire off the shots, Karsten after him, his hair standing on end. The stones went crashing over—the next moment we heard a doleful shriek from below. Peter came rushing down to the dungeon, ashy-gray under his freckles, crying:

"Oh, Mother—Mother——"

We all dashed up instantly. Down below the fort, just at the foot of the precipice, stood the dean's little crooked wife, with a purple kerchief over her head and one slender hand held up in the air. The stone, which had been fired off in honor of the ladies, lay less than two feet from her![Pg 36]

Even to this day I am sorry that I didn't run to her at once and go back with her down the hill. That didn't occur to any of us, I think. When we found that she hadn't been hit, but was only terribly frightened at seeing the great stone in the air right over her, we almost thought, up there in the fort, that it was rather unseemly of the dean's wife to scream out so.

She crept down the hill alone; she had just gone up to see to a white bed-spread that was hanging on a bush to dry.

Our festive mood was gone, however,—shocked out of us, as it were.

Karsten struck into the air with clenched fists, as he always does when he is excited. It wasn't so very dangerous, he protested; for if he had been the dean's wife, of course he would have seen what direction the stone was taking in the air, and if it went that way, why then he would have jumped to one side—like this—and if the stone went the other way, why then you could just jump to the other side. Besides, if the dean's wife had been, as she ought[Pg 37] to have been, as strong as Nils Heia, for instance, then she might have stood perfectly still, fixed her eyes on the stone, held her hands to catch it, and tossed it away. Yes, wouldn't Nils Heia have done it that way? Wouldn't he be strong enough for that?

But very soon the horror of it came over me; just think, if Peter had killed his own mother! I remember clearly that I wouldn't have anything more either to eat or drink, and Nils Trap teased me, and said I had grown quite white around the nose with fright.

As we sat there looking at each other and not able to get started on anything again, suddenly we heard a voice:

"Peter."

"That's Father," said Peter, and crouched away down so that he couldn't possibly be seen from below.

"Hush—sh—keep still—hush!" We lay in a heap, frightened and silent.

"Peter," came again from below. "Come down this instant. I know you are up there."[Pg 38]

"Hush—just keep still, not a sound."

Dead silence.

"Well, if you don't come at once——" The dean was furious; we could hear that in his voice.

"I've got to go," said Peter, standing up. "I've got to—I've got to——" He scrambled out; the rest of us just stuck our heads up to see what would happen.

There stood the dean with no hat, just in his wig, and furiously angry. It was no fun to be Peter now. He was everlastingly slow about clambering down. The dean scolded up towards our six heads, sticking out of the dungeon:

"Yes, just try such a thing again—just try it—your backs shall suffer for it—big boys and girls as you are—killing people with stones!"

"Yes, but we didn't kill anybody," called Karsten.

I was perfectly appalled at Karsten's daring to call out such a thing to the dean, who, however, paid not the least attention; Peter had at[Pg 39] last come within his reach, so he had something else to do.

First a box on one ear: "I'll teach you,"—then a box on the other ear: "almost killing your own mother"—and he kept on hitting. But only think; although I felt so terribly sorry for Peter, so sorry that I believe I should have been glad to take the blows in his place—I was as much to blame as he—yet there was something so fearfully exciting in watching Peter and the dean down there, that I almost felt disappointed when the dean took Peter by his left ear and dragged him away. The boys had lately made a little path down the hill and to the back gate of the dean's garden. It was lucky for Peter that there was some sort of a beaten track, now that he was being led along it by the ear.

"You can depend upon it that Peter will get a thrashing," said Karsten, who also felt the excitement of the moment. "But if it were I"—he grew very earnest—"I'd throw myself on my back and stretch my legs up in the[Pg 40] air and kick so that nobody could come near me. He shouldn't beat me, no indeed, he'd soon find that out."

It was all over with the celebration. Ezekiel proposed that we should finish up the refreshments—we divided the cake equally—and then we clambered down; but we took the path to our garden, not to the dean's. We only whispered, we didn't speak a single loud word, till we got down. We got a scolding, a thorough scolding, from the dean, but Mother cried when she heard what a calamity we had nearly brought about. And I minded Mother's tears much more than I did the dean's scolding.

Afterwards, when we asked Peter what had happened to him, he didn't answer, but just smiled feebly.

Yes, that is the way our Seventeenth of May celebration was interrupted!

The dean took Peter by the left ear and dragged him

away.—Page 39.

The dean took Peter by the left ear and dragged him

away.—Page 39.

Well! I didn't travel entirely alone, either, you must know; for, you see, I had Karsten with me. But he was only nine years old that summer, so that it was about the same or even worse than traveling alone. To make a journey with small children by steamer isn't altogether comfortable, as any grown person will tell you.

It is curious how tedious everything gets at home in your own town when you have decided to make a journey. Whatever it might be that the boys and girls wanted to play—whether it was playing ball in the town square, or hide-and-go-seek in our cellar, or caravans in the desert up on the hilltop, or frightening old Miss Einarsen by knocking on her window[Pg 42] (which is generally great fun)—it all seemed stupid and tiresome beyond description now.

For I was going to travel, going on a journey, and that is the jolliest, jolliest fun! Alas! for the poor stay-at-homes who couldn't go away but had to walk about the same old town streets, and smell street dust, and gutters, and stale sea-water in by the wharves.

But I have clean forgotten to tell you where I was going. Mother has a sister who is married to a minister. They live fifteen or twenty miles from our town and we go there every summer. But this summer, it had been decided that Karsten and I should go there alone for the first time.

The afternoon before we were to set out I went down back of our wood-shed, where all the boys and girls that I go with generally come every afternoon. It was hot enough to roast you and awfully dry and dusty; but I took my new umbrella down with me all the same. It wasn't really silk, but I had wound it and fastened it so tightly together that it looked just[Pg 43] as slender and delicate as a real silk one. I wouldn't play ball with the rest of them. I just stood and swung my umbrella about.

"Have you got a new umbrella?" said Karen. "Is it a silk one?" asked Netta. "You've got eyes in your head," I answered. And so they all thought it was a silk one. I couldn't play ball with them, I said, because I had to go in and pack. Now that wasn't true at all, for I knew well enough that Mother had done all the packing; but it sounded so off-hand and important. They all teased me to stay down with them for a while, but no indeed, far from it. "I have too much to do. I start to-morrow morning early. Good-bye."

"Good-bye and a happy journey," shouted the company.

When I got in the house I was a little sorry that I hadn't stayed out with the others; for I hadn't a thing to do but go from one room to another and tighten the shawl-straps for the twentieth time at least. I thought the afternoon would never come to an end.[Pg 44]

Early in the morning, before it was really light, the maid came into the room and shook me and whispered, "Now you must get up. It's half-past four o'clock. Get up! The steamer goes at half-past five, you know." Oh, how dreadfully sleepy I was, but it was great fun all the same. The sun was not shining into my room yet, but on the church tower it glowed like a fire. The weather was going to be good. Hurrah! All the doors and windows of the sleeping-rooms stood wide open. It was so sweet and fresh and quiet everywhere, fragrant with the smell of the trees and fresh garden earth outside. We went in to say good-bye to Father and Mother at their bedside.

"Remember us to everybody and be nice, good children," said Mother.

"Don't lose everything you have with you," said Father. Humph! Lose—Father seemed to forget that I was nearly grown up now.

As we went down the hill, the stones under the elm-trees were still all moist with dew. Oh! how quiet it was out-of-doors! Suddenly away[Pg 45] down in the town a cock crew. Everything seemed very strange.

Karsten and I ran ahead and Ingeborg, the maid, came struggling after us with our big green tine.[1] Suddenly a desperate anxiety came over me. Suppose the steamboat should go off and leave us! Then how we ran! We left Ingeborg and the tine and everything else behind. When we turned round the corner into the market square, the sun streamed straight into our eyes and there by the custom-house wharf lay the steamboat, with steam up and sacks of meal being put on board. Karsten and I dashed across the square. Pshaw! we were in plenty of time. There wasn't a single passenger aboard yet. It is a little steamboat, you know, that only goes from our town over to Arendal. I got Karsten settled on a seat, kneeling and facing the water, and then established myself in a jaunty, free and easy manner by the railing as if I were accustomed to travel. Ole Bugta and Kristen Snau and all the other[Pg 46] clodhoppers on the wharf should never imagine that this was the first time I had been aboard a steamboat.

[1] Tine (pronounced tee´ne) a covered wooden box with handle on top.

Soon that skin-and-bone Andersen, the storekeeper, got on the boat, and then came little Magnus, the telegraph messenger, jogging along. Magnus is really a dwarf. He is forty years old and doesn't reach any higher than my shoulder; but he has an exceedingly large old face. He clambered up on a bench. He has such short legs that when he sits down his legs stick straight out into the air, just as tiny little children's do when they sit down. Then came Mrs. Tellefsen, in a French shawl, and dreadfully warm and worried. "When the whistle blew the first time, I was still in my night-clothes," she confided to me.

The whistle blew the third time. I smiled condescendingly down to Ingeborg, our maid, who stood upon the wharf. I wouldn't for a good deal be in her shoes and have to turn back and go home again now. Far up the street appeared a man and woman shouting and calling[Pg 47] for us to wait for them. "Hurry up! Hurry up!" shouted the captain. That was easier said than done; for when they came nearer I saw that it was that queer Mr. Singdahlsen and his mother. Mr. Singdahlsen is not right in his mind and he thinks that his legs are grown together as far down as his knees. So he doesn't move any part of his legs in walking except the part below his knees. Of course he couldn't go very fast. His mother pushed and pulled him along, the captain shouted, and at last they came over the gangway and the steamboat started.

The water was as smooth and shining as a mirror, and it seemed almost a sin to have the steamboat go through it and break the mirror. Over at the Point the tiny red and yellow houses shone brightly in the morning light and the smoke from their chimneys rose high in the quiet air.

Then my troubles with Karsten began. Yes, I entirely agree that children are a nuisance to travel with. In the first place, Karsten[Pg 48] wanted to stand forever and look down into the machinery room. I held on to him by the jacket, and threatened him and told him to come away. Far from it! He was as stubborn as a mule. Humph! a great thing it would have been if he had fallen down between the shining steel arms of the machinery and been crushed! O dear me! At last he had had enough of that. Then he began to open and shut the door which led into the deck cabin; back and forth, back and forth, bang it went!

"Let that be, little boy," said Mr. Singdahlsen. Karsten flushed very red and sat still for five whole minutes. Then it came into his head that he absolutely must see the propeller under the back of the boat. That was worse than ever, for he hung the whole upper part of his body over the railing. I held fast to him till my fingers ached. For a minute I was so provoked with him that I had a good mind to let go of him and let him take care of himself;—but I thought of Mother, and so kept tight hold of him.[Pg 49]

We went past the lighthouse out on Green Island. The watchman came out on his tiny yellow balcony and hailed us. I swung my umbrella. "Hurrah, my boys," shouted Mr. Singdahlsen in English. "Hurrah, my boys," imitated Karsten after him. Little Magnus dumped himself down from the seat and waved his hat; but he stood behind me and nobody saw him. It was really a pretty queer lot of travelers.

Just then the mate came around to sell the tickets. Father had given me a five-crown note for our traveling expenses. As Karsten and I were children and went for half-price, I didn't need any more, he said. So there I stood ready to pay.

"How old are you?" asked the mate.

Now I have always heard that it is impolite to question a lady about her age; I must say I hadn't a speck of a notion of telling that sharp-nosed mate that I lacked seven months of being twelve years old.

"How old are you?" he asked again.[Pg 50]

"Twelve years," said I hastily.

"Well, then you must pay full fare."

I don't know how I looked outside at that minute. I know that inside of me I was utterly aghast. Suppose I didn't have money enough! And I had told a lie!

Now my purse is a little bit of a thing, hardly big enough for you to get three fingers in. I took it out rather hurriedly—everything that I undertake always goes with a rush, Mother says. How it happened I don't know, but my five-crown note whisked out of my hand, over the railing and out to sea.

"Catch it! Catch it!" I shouted.

"That is impossible," said the mate.

"Yes, yes! Put out a boat!" I cried. All the passengers crowded together around us.

"Did the five crowns blow away?" piped Karsten.

"Was it, perhaps, the only one you had?" asked the mate. Ugh! how horrid he was. Storekeeper Andersen and Mrs. Tellefsen and[Pg 51] the mate laughed as hard as they could. Karsten pulled at my waterproof.

"You're a good one! Now they will put us ashore because we haven't any money. You always do something like that!"

"Are you going to put us ashore?" I asked.

"Oh, no," said the mate. "I will go up to your father's office and get the money some time. That's all right."

Pshaw! that would be worse than anything else. Father would be raving. He always says I lose everything.

"You'll catch it from Father," whispered Karsten.

Oh, what should I do! What should I do! Karsten and Mr. Singdahlsen clambered up on some rigging away aft to get sight of the five-crown note. Mr. Singdahlsen peered through the hollow of his hand and both he and Karsten insisted that they saw it. But that couldn't help us any.

Oh! how disgusting everything had become all at once. The visit at Uncle's and Aunt's[Pg 52] would be horrid, too. To go there alone in this way, and have to talk alone with Uncle, a minister, and all the other grown-up people at the rectory—it would be disgustingly tiresome. There was nothing that was any fun in the whole world. It would be disgusting to go home again; for Father would be so dreadfully angry—and it was most disgusting of all to be here on the steamboat where everybody laughed at me.

And all on account of an old rag of a five-crown bill which had blown away. Besides, I had told a lie and said I was twelve years old. Oh-oh-oh! how sad everything was!

I sat with my hand under my cheek, leaning against the railing and staring into the sea. All at once a plan occurred to me which I thought a remarkably good one then. Now I think it was frightfully stupid. I would ask the mate if he wouldn't take something of mine as payment for our passage.

I had a little silver ring—one of those with a tiny heart hanging to it;—I thought of that[Pg 53] first. I took it off of my finger and looked at it. It was really a tiny little bit of a thing—it couldn't be worth so very much. At home I had a pair of skates, sure enough. I would willingly sell them. But I couldn't possibly ask the mate to go up into our attic and get them and sell them for me. What in the world should I give him? Suddenly a brilliant idea struck me. My new umbrella—he should have my new umbrella. And I would tell the mate at the same time that I had made a mistake, that I wasn't twelve years old, only eleven years and five months. I took the umbrella and went quickly across the deck to find the mate. To be on the safe side I took the ring off of my finger and held it in my hand. It might be he would want both ring and umbrella. But it was impossible to find him. I wandered fore and aft and peeked into all the hatchways—but I couldn't get a glimpse of that sharp nose of his anywhere. Finally I discovered him sitting in a little cabin, writing.

I established myself in the doorway and[Pg 54] swung my umbrella. To save my life I couldn't get out a single word of what I had planned to say. Think of having to say "I told you a lie!"

"Do you want anything?" asked the mate at last.

"Oh, no!" I said hastily. "Well, yes. How far is it to Sand Island now?"

"An hour's sail, about;"—at the very minute that he was speaking these words a terrible shriek was heard from aft, a loud shriek from several people all screaming as hard as they could. I never was so scared in my whole life. The mate almost pushed me over, he sprang so quickly out of the door. All the people aft were crowded at one side. In the midst of the shrieks and cries I heard some one say, "Man overboard!"

O horrors! It must be Karsten! I was sure of it. I hadn't thought of him or taken any care of him for the last ten minutes. I hardly know how I got aft, my knees were shaking so. The steamboat stopped and two sailors were already[Pg 55] up on the railing loosing the life-boat.

"Karsten! Karsten! Karsten!" I cried. All at once I saw Karsten's light hair and big ears over on a bench. He was throwing his arms about in the air and was frightfully excited. "This is the way he did," shouted he; "he hung over the railing this way, looking for the five crowns."—It was Mr. Singdahlsen who had fallen overboard. Oh, poor Mrs. Singdahlsen! She cried and called out unceasingly.

"He is weak in the understanding!" she cried, "and therefore the Lord gave me sense enough for two—so that I could look after him;—catch him—catch him. He will drown before my very eyes."

I held Karsten by the jacket as in a vise. I was going to look after him now. The boat was by this time close to Mr. Singdahlsen. They drew his long figure out of the water and laid him in the bottom of the boat. The next minute they had reached the side of the steamer[Pg 56] again, clambered up with Singdahlsen, and laid him on the deck. He looked exactly as if he were dead. They stripped him to his waist, and then they began to work over him according to the directions in the almanac for restoring drowned people. If I live to be a million years old I shall never forget that scene.

There lay the long, thin, half-naked Singdahlsen on the deck, with two sailors lifting his arms up and down, Mrs. Singdahlsen on her knees by his side drying his face with a red pocket-handkerchief, the sun shining baking hot on the deck, and the smoke of the steamer floating out far behind us in a big thick streak. At length he showed signs of life and they carried him into the cabin. Then, what do you suppose happened? Mrs. Singdahlsen was angry at me! Wasn't that outrageous? The whole thing was my fault, she said, for if I hadn't lost the five crowns, her son wouldn't have fallen overboard.

"Now you can pay for the doctor and the apothecary, and for my anxiety and fright besides,"[Pg 57] said Mrs. Singdahlsen. But everybody laughed and said I needn't worry myself about that.

"You said yourself that you had sense enough for two, Mrs. Singdahlsen," said Storekeeper Andersen.

"I haven't met any one here who has any more sense," said Mrs. Singdahlsen stuffily.

"Humph!" thought I to myself, "if I had to pay for Mrs. Singdahlsen's fright the damages would be pretty heavy."

Just then we swung round the point by the rectory, where Karsten and I were going to land. Uncle's hired boy was waiting for us with a boat. I recognized him from the year before. He is a regular landlubber, brought up away back in a mountain valley, and is mortally afraid when he has to row out to the steamboat. His face was deep red, and he made such hard work of rowing and backing water, and came up to the steamboat so awkwardly, that the captain scolded and blustered from the bridge. At last we got down into[Pg 58] the rowboat and were left rocking and rocking in the steamer's wake.

John, the farm boy, mopped his face and neck. He was all used up just from getting a rowboat alongside the steamer!

"Whew, whew! but it's dreadful work," said he.

The rectory harbor lay like a mirror. The island and trees and the bath-house stood on their heads in the clear, glassy water; and between the thick foliage of the trees there was a wide space through which we could see the upper story of the rectory and the top of the flagstaff. It is worth while to go traveling after all. I won't give another thought to that old rag of a five-crown bill.

Well; what I am going to tell about now hasn't the least thing to do with St. John's Day itself,—you mustn't think it has; not the least connection with fresh young birch leaves and strong sunshine and Whitsuntide lilies and all that. Far from it. It is only that a certain St. John's Day stands out in my memory because of what happened to me then.

Yes, now you shall hear about it. First I must tell you of the weather. It was just exactly what it should be on St. John's Day. The sky looked high and deep, with tiniest white clouds sprinkled over the whole circle of the heavens, and the sunshine was glorious on the hills and mountains and on the blue, blue sea.

Since it was Sunday as well as St. John's[Pg 60] Day, I was all dressed up. To be sure my dress was an old one of Mother's made over, but the insertion was spandy new and there was a lot of it. I'd love to draw a picture of that dress for you, if you wanted to have one made like it.

Perhaps I had best begin at the very beginning, which was really Karsten's stamp collection. He does nothing but collect stamps, and talk and jabber about stamps the whole day long. He swaps and bargains, and has a whole heap of "dubelkits," as he calls them. These duplicates he keeps in a tiny little box. He means to be very orderly, you see.

To tell the truth, Karsten is perfectly stupid about swapping. The other boys can fool him like everything. He doesn't understand a bit how to do business, and so I always feel like taking charge of these stamp bargainings myself. If I see a boy I don't know very well, peeping around the corner or sneaking up the hill, I am right on hand, for boys that want to trade never come running; they act as if they[Pg 61] were spying round and lying in wait for some one.

The instant Karsten sees them he comes out with his stamp album. He stands there and expounds and explains about his stamps, with such a trustful look on his round pink face, while the other boys watch their chance to fool him; and before he knows it, some of his very best specimens are gone. That's the reason why I have taken hold.

As soon as I see a suspicious-looking boy on the horizon—that is to say on the hill—I go out and stand at the corner in all my dignity and won't budge, and I always put in my word you may be sure. Karsten doesn't like it, but anyway, he had me to thank for a rare Chili stamp.

But it was that very same rare stamp that brought about all my trouble on St. John's Day, because Nils Peter cheated that stupid donkey of a Karsten out of it the next time he saw him. And that was on St. John's Day, the very day after I had got it for him.

"I believe you would give them your nose, if[Pg 62] they asked for it," I said to Karsten. "You'd stand perfectly still and let them cut your nose nicely off, if they wished."

"You think you are smart, don't you?" said Karsten fiercely.

As Olaug came out just then (she is my little sister, you remember), I shouted to her:

"Run as fast as you can to Nils Peter and tell him Inger Johanne says for him to give up that Chili stamp instantly. I'll hold Karsten while you run."

He would have run after Olaug to catch her before she should have time to ask Nils Peter for the stamp, for he thought that would be too embarrassing.

Just as I got a good grip on Karsten, Olaug started. Oh, how she ran!—just like a race-horse, with her head high. Her hat fell off and hung by its elastic round her neck. She ran down the hill and up over Kranheia at top speed.

But you may believe I had a job of it standing there and holding fast to Karsten. He[Pg 63] pushed and he struck and he scolded. My! how he did behave!

But I held on and watched Olaug to see how far she had got. I was high on the hill, you know, and could see a long way.

"O dear! Olaug will burst a blood-vessel running like that," I thought. My! now she is there—now away off there. Karsten squirmed and struggled; now Olaug is on the path up Kranheia,—she's slowing down a little.

Impossible for me to hold Karsten any longer. I had to let go. He was off like an arrow, his hair standing up straight and his feet pounding the ground like a young elephant's.

O pshaw! Running like that he would soon catch Olaug. It was frightfully exciting, like a horse-race or a hunt after wild animals.

Well, that isn't a very good comparison, for nothing could be less like a wild animal than Olaug; but it was awfully exciting to see whether she would keep ahead and get the Chili stamp from Nils Peter.[Pg 64]

So that I might see better how the race ended I sprang up to our chicken-yard, or rather beyond it, on our own hill. You could see the whole path up over Kranheia better from there than from any other place. But just where I must be to see best was that awfully high board fence, too high for me to see over, that went from the chicken-yard quite a long way beyond on the hill.

Pooh! What of it? I just wiggled a board that was already loose, pulled it away and stuck my head in the opening. It was a little narrow but I got my head through. Oh—oh! Karsten had caught up to Olaug and run past her like an ostrich at full speed—I've always heard that an ostrich runs faster than anything else in the world—yes, there he was swinging in towards Nils Peter's house.

O pshaw! Now that Chili stamp was lost for ever and ever.

Olaug had plumped herself right down; she had to sit still and get her breath, poor thing!

Now that there was nothing more for me to[Pg 65] watch, I started to draw my head back out of the narrow opening between the thick boards. But, O horrors! It stuck fast! I couldn't possibly get it back. I turned and twisted my head this way and that, and up and down; I tried to pull and squeeze it back, but no, that was utterly impossible. How in the world I had ever got my head through the opening in the first place I can't understand to this day, but that I had got it through was only too sure.

New struggles to get loose—I thought I should tear my ears off—Goodness gracious, what should I do!

At first I wasn't a speck afraid. I just wriggled and pulled as hard as I could. But when I realized that I simply could not free myself, a sort of terror came over me.

Just think—if I never got my head out? Or suppose there came a cross dog and bit me while my head was as if nailed fast in the fence! And suppose nobody found me—(for of course nobody would know that I had run up here beyond the chicken-yard)—and per[Pg 66]haps I should have to stay caught in the fence the whole night, when it was dark.

I cried and sobbed, then I called; at last I screamed and roared. I heard the hens in the yard flap their wings and run about wildly, evidently frightened by the noise I made.

Down on the road, people stood still and gazed upward; then of course I shrieked the louder. But no one looked up to the chicken-yard; and even if they had, they couldn't very well see, from so far down, a round brown head sticking through a brown fence. I roared incessantly, and at last I saw a woman start to run up the hill—and then a man started—but they did not see me and soon disappeared among the trees, although I kept on bawling, "Help! I am right here! I am caught in the fence!"

Just then I saw Karsten and Nils Peter come out of Nils Peter's house. They stood a moment as if listening, and naturally they recognized my voice.

Then they started running. If Karsten had[Pg 67] raced over there, he certainly raced back again, too.

I kept bawling the whole time: "Here! here! in the fence! I am stuck fast in the fence!" It wasn't many minutes before both Karsten and Nils Peter stood behind me.

"Have you gone altogether crazy?" said Karsten in the greatest astonishment.

I felt a little offended, but there's no use in being offended when you haven't command over your own head, so I said very meekly:

"Ugh! such a nuisance! My head is stuck fast in here. Can't you help me?"

Would you believe it? They didn't laugh a bit—awfully kind, I call that—they just hauled and pulled me as hard as they could; it fairly scraped the skin off behind my ears and I thought I should be scalped if they kept on.

"No, it's no use," I said, crying again. "Run after Father, run after Mother, get everybody to come—uh, hu, hu!"

Well, they came. I couldn't see them, but I could hear the whole lot of them behind me.[Pg 68]

Now there was a scene! The same story began again; they pulled and twisted my head, Father gave directions, I cried and Olaug cried and everybody talked at once.

"No," said Father at last, "it can't be done. Hurry down to Carpenter Wenzel and ask him to come and to bring his saw with him."

"Uh, huh! He'll saw my head off!" I wailed.

But Mother patted me on the back and comforted me, and all the others standing behind kept saying it would be all right soon, while I stood there like a mouse in a trap and cried and cried.

But it was Sunday and the carpenter was not at home.

"Run after my little kitchen saw then," said Mother. "Bring the meat-axe, too," called Father.

Oh, how would they manage? It seemed to me my head would surely be sawed or chopped to pieces.

They just hauled and pulled me as hard as they

could.—Page 67.

They just hauled and pulled me as hard as they

could.—Page 67.

Well, now began a sawing and hammering around me. When Mother sawed I was not afraid, but when Father began I was in terror, for Father, who is so awfully clever with his head, is so unpractical with his hands that he can't even drive a nail straight. So you can imagine how clumsy he would be about getting a head out of a board fence.

The others all had to laugh finally, but I truly had no desire to laugh until my head was well out. In fact, I didn't feel much like laughing then either, for really it had been horrid.

Ever since that time Karsten and Nils Peter have teased me about that Chili stamp. They say that getting my head stuck fast was a punishment for putting my oar in everywhere. Think of it—as if I did try to manage other people's affairs so very much!

But it certainly is horrid when you can't control your own head. You just try it and see.

Never in my life have I traveled so far as when Mother, Karsten and I visited Aunt Ottilia and Uncle Karl. And so unexpected as that journey was! I hardly had time to rejoice over it, even. It was all I could do to get time to write a post-card to Mina, who was visiting her grandmother at Horten, to ask her to come down on the wharf and see me, when the steamer stopped there on its way.

When we are to start on a journey, Father is always terribly afraid that we shall be too late for the steamboat.

"Hurry—hurry," he keeps saying, as he goes in and out. Mother gets tired of it, but that makes no difference. Besides, all husbands are like that, Mother says; unreasonable when other people go away, and still worse to travel with.

An hour and a half before the steamboat[Pg 71] could be expected, we had to trudge down to the wharf; for Father wouldn't give in. Mother had to sit on a bench down there, with meal-sacks all around her; but Karsten and I and Ola Bugta and the other longshoremen on the wharf went up on Little Beacon to look for the steamboat.

People usually wish for good weather when they are going to travel; but I wish for a storm; for to plunge through the waves, up and down, must be awfully jolly. And besides, it is so stupid that I have never been seasick, and don't know what it's like.

"What kind of weather do you think we'll have, Ola Bugta?" I asked him, up on Little Beacon.

Ola Bugta took the quid out of his mouth. "Oh, it is fine weather outside there." O dear, then we should have good weather to-day, too!

Well, at last we saw a faint streak of smoke far off in the mist. Karsten and I almost tumbled head over heels down the hill to tell Mother that now we saw the smoke. Karsten[Pg 72] had a new light spring coat for the journey. He looked queer in it, for it was altogether too long for him. I took the liberty of saying that he looked like a lay preacher in it; not that I ever saw a lay preacher in a light spring coat; but Karsten looked so tall and proper all at once.

Hurrah! now the steamer was in Quit-island Gap. How much more interesting a steamer looks when you are going to travel on it yourself! It made a wide sweep when it came from behind the island, and glided in a big graceful curve up to the wharf. There were a great many passengers on the boat. As soon as the gangway touched the wharf, I wanted to go on board, but the mail-agent pushed me aside. "The mail first," said he. But I ran on right after the mail.

Oh, how awfully jolly it was! The deck crowded with passengers, and trunks, and tines, and traveling-bags; the delightful steamboat smell; all my friends standing on the wharf; and I tremendously busy carrying[Pg 73] Mother's portmanteau and hold-all on board. I certainly went six times back and forth across the gangway. O dear! so many boxes had to be put on board, I thought we should never get off. I nodded and nodded to every one on the wharf. At last I nodded to Ola Bugta; but he didn't nod back; he just turned his quid in his mouth.

Finally we started.

Whenever I go down on the wharf to watch the steamboat, it seems to me almost as if it were always the same people traveling. But to-day there were a whole lot of different kinds of people.

The first person I noticed was a tall old lady who had a footstool with her. Think of traveling with a yellow wooden footstool! If she had only sat still,—but she and the footstool were constantly on the go. At last she must have thought that I looked exactly cut out to carry the stool for her.

"Little girl," she said, "you're a good girl, aren't you, and will help me a little?" After[Pg 74] that I couldn't go anywhere near her without there being something I must do for her. The worst was hunting for a parasol that she couldn't find.

"There is lace over the weak place in it, my dear," said she. After this instruction I did find it. Then she offered me some candy, but it looked so gummy that I gave it to Karsten. I saw that he had to chew it well.

Mother had met a childhood friend and they sat talking together incessantly. Just think, it was twenty-two years since they had seen each other. How queer it would be to see my best friend Mina again in twenty-two years, with some of her teeth gone and a double-chin.

For a wonder Karsten sat perfectly still by Mother's side with his hands deep in the pockets of his new coat; and he didn't open his mouth; but I ran about the whole time. I wasn't still an instant.

Off by herself on a bench sat a fat woman wrapped in a shawl, with a big covered basket which she dipped down into every other minute.[Pg 75] Both sausage and fancy cakes came up out of the basket. She looked at me as if she would like to offer me something, and munched and munched.

Before long I went down below. When you were in the saloon the boat shook delightfully; the big white lamps that hung from the ceiling rattled and jingled, and there was such a charming steamboat smell. Everywhere on the reddish-brown plush sofas, ladies and gentlemen with steamer-rugs over them lay drowsing. I took a newspaper, for it looked grown-up to sit reading; but I didn't want to read the paper, after all, so I went straight up on deck again.

But the weather had changed! It was not anything like so bright as when we started. There were already little white-capped waves, and the wind whistled across the deck; and now the ship began to plunge enough to suit me.

Oh—up—and—down—up—and—down!

I crept to the very stern and sat down beside the flag; for I thought it looked as if the boat[Pg 76] rocked most there. You know, I wanted to rock as much as possible.

The steamer laid its course more out to sea. Each time we went down into the waves the water stood foaming white around the bow. The wind took a fierce grip on the awning as if it would tear it to pieces, and my hair blew about my face; this was just what I liked! Hurrah!

But little by little all the other passengers disappeared from the deck. Mother and her friend were the first; Karsten tagged after them. Mother called out something to me at the moment she was disappearing down the cabin stairs, but I didn't know what it was.

Oh, everything was so glorious! This was fun; if only they would go farther out to sea, farther yet—farther yet.

The lady with the footstool had disappeared long ago. The yellow footstool was taking care of itself and tumbled from one side to the other. Then a stewardess came up with a message from Mother that I should come[Pg 77] down-stairs at once. That must have been what she said when she was disappearing down the cabin stairs.

In the cabin Mother and Karsten lay pale as death, each on a sofa. I must lie down, too, Mother said. Really, I hadn't any wish to lie down on a sofa now that the fun on deck was just beginning; but as long as Mother said so——

Hurrah! Cups and plates and trays crashed over each other in the serving-room, people fell over each other on the stairs. The traveling-wraps hanging out in the corridor, and the green curtains before the staterooms swung violently back and forth, the ship tossed so.

"Isn't there any one that will help me?" begged a complaining but familiar voice behind one of the curtains. That was certainly the lady with the footstool. I jumped behind the curtain; yes, so it was. She was sitting on the edge of her berth; she said she didn't believe she could get out again if she squeezed herself in, she was so fat.[Pg 78]

You may be sure she set me to work. She had lost all her things, one wrister here and one wrister there; I had to find everything, a bouquet in the saloon, and overshoes under the sofa. Finally it was the footstool up on deck.

It was only fun to run up on deck again. Of course I tumbled from one side to the other and laughed and laughed, enjoying it hugely.

When I was down-stairs again, the stewardess must have thought that I flew around too much and was in the way, for she pushed me suddenly into a stateroom. There sat the woman with the covered basket.

"Isn't there any one that will help me?" the complaining voice kept on in the stateroom opposite us.

"Can you imagine why such folks travel?" said the woman, jerking her head in the direction the voice came from, "when they have their good home, and their good bed and everything to suit them—why should they rove around from pillar to post?"

"What are you traveling for?"[Pg 79]

"Oh, I have been on a little trip off to Grimstad, to my sister's, for three weeks; I didn't think I should stay longer than a week at the most, so I didn't take more than one change with me, and you must excuse me if I look rather untidy."

No, I assured her, she didn't look in the least untidy. But she was awfully funny, I can tell you. She told me the whole story of her life. Her husband was a skipper; twice she had been with him to the Black Sea, "and once across the equator as far as a place they call Buenos Ayres, and it was so elegant, my dear, with riding policemen in the streets."

And the whole time we were talking she chewed and munched. For there had been some one in Grimstad named Gonnersen, who was so polite that he had bought a whole basket of cakes for her on the journey. "Will you condescend to help yourself to a cake?" she said suddenly.

"Gonnersen was so polite"—was the last I heard as she crossed the gangway at Fredriksvern.[Pg 80] That was where she lived. Then she stood on the wharf and waved to me, still eating.

Now there was only Larvik and Vallö before we got to Horten; there I was to meet Mina;—hurrah, hurrah, how glad I was!

But it is certainly a good thing that you don't know what is going to happen; for it was at Horten I got left behind, all because the steamer rang only once at the Horten wharf; and that, I must say, is a shame, when people have bought their tickets to go on farther.

Yes, it was disgusting;—but now you shall hear exactly how it happened. When we got to Horten, Mina stood on the wharf with a new red parasol. Mother and Karsten were still in the cabin lying down. I ran ashore at once, you may be sure. Mina and I thought it was great fun to talk together; for we had not seen each other for more than two weeks.

She told me the whole story of her life.—Page 79.

She told me the whole story of her life.—Page 79.

"Grandmother lives up there," said Mina, "up there, see—come here, only two or three steps farther, and you'll see better; see, there is the garden, and the doll-house with red curtains. Do you see the doll-house?—only a few steps more,—and there is the bowling-alley in Grandmother's garden——"

We ran up and up; then the steamer bell rang. "It will be sure to ring three times," I said.

"Oh, surely," said Mina, and went on explaining: "Do you see that white boat with a flag——"

I heard a suspicious sound from the steamer, and turned round as quick as lightning. Yes, really, it was putting off from the wharf; first it backed a little, and then started forward full speed. I dashed with great leaps down the road and across the wharf.

"Stop—stop—stop, I am going with you——"

But if you think there was any one who cared whether I called or not, you are mistaken. Not a person on board even turned his head, and the longshoremen on the wharf laughed as[Pg 82] hard as they could. There went the steamer with Mother and Karsten!

I wonder if you can imagine my feelings; I was in such despair that I plumped myself down on the wharf and cried. What would Mother think? She would certainly be afraid that I had fallen overboard when I disappeared all at once without leaving a trace;—and what would Father say?—and how in the world could I get to Uncle Karl's now?

Oh, how I cried that time on the wharf at Horten! At last I had to go home with Mina. And Mina's grandmother was very sweet, she really was; and Horten was really a pretty town, and I can well believe there were many nice people in it; but as for me, I thought it was horrid to be there. I didn't care about the doll-house with red curtains, or anything, though it was the prettiest doll-house I ever saw in my life, with two little rocking-chairs with little embroidered cushions, in the parlor, and little pudding-forms and colanders on the kitchen walls.[Pg 83]

But Mina's grandmother telegraphed to Mother at Dröbak that I was safe and sound at Horten; and late in the evening a telegram came from Mother at Uncle Karl's, saying that I was to borrow some money from Mina's grandmother and that I was to take a little steamer up the fjord early the next morning.

Such queer things are always happening to me! I never heard of any girl who was left behind as I was on the wharf at Horten. Mina's grandmother wanted me to stay there a few days, and would have telegraphed to Mother to ask if I might; but I didn't want to stay, for I longed so unspeakably for Mother. That night I lay awake for hours and hours, and began to feel that I should never see Mother again.

Well, in the gray light of the next morning I sat on the damp deck of a little steamer, with two big bags of cakes. Mina stood on the wharf waving and yawning too, for she wasn't used to getting up at five o'clock.[Pg 84]

I was very cold, and ate one cake after another, and dreaded what Mother would say when I got to my journey's end. It would be a very different arrival from what I had expected.

There were no other passengers on board, but a big dog who stood tied, with his address on his back. And I didn't have much pleasure with him either, for he growled at me when I patted him.

Later the captain came and talked with me. When I told him that I had been left behind on the Horten wharf the afternoon before, he laughed so that he got purple in the face. Now can you see anything to laugh at? For all that, the captain was very kind, for he let me go up on the bridge with him, and there I stayed all the time until we arrived.

On the wharf stood Uncle Karl, Mother, and Karsten waiting. Mother shook her head and looked much displeased; but Uncle Karl, with his big white mustache, laughed and nodded.

"I'm thankful to see you again," said[Pg 85] Mother. "You must know I was worried about you."

"Beautiful eyes, the puss has," said Uncle Karl suddenly.

I looked around astonished, for there didn't seem to be any puss anywhere. But only think! he meant me. I have looked carefully at my eyes since, but I don't think they are beautiful at all, for they are too round and look so surprised.

Oh, what fun we had at Uncle Karl's! I do not know that I should ever come to an end if I tried to tell about it, so I won't begin, for I have a tremendous gift of gab when I once get started;—at least that is what everybody says.

We have an awfully cosy cellar, you must know. Of course the whole house is old and rather tumbledown, so the cellar is nothing very fine; but it is awfully cosy and exactly right for playing in, in bad weather. I don't know a cellar in the whole town that is cosier; and I am fairly well acquainted with all of them, you may be sure.

Our cellar isn't underground. It is a high basement and in it is a big brewery and laundry, a big servant's room, and a big wine cellar where there is never any wine; on the other side of the basement is the storeroom for food and the potato cellar. The walls are brown and dark just from age; and the floor rocks so that I often wonder that the big casks and barrels, and fat Christine and Maren the washerwomen, who are forever washing there, do[Pg 87] not fall through, perhaps into some deep abyss underground. But it must be tough, that floor, for it still holds.

One day there was disgusting weather. Withered leaves flew around your ears and the streets were soaking wet and muddy. Nils, Peter, Karen and Antoinette had come up to our hill in order to have fun of some kind in the drizzling weather; and we hit upon playing hide-and-seek in our cellar. We divided into sides; Peter, Karsten and I on one side and the other three on the other. Nils, Antoinette and Karen hid themselves first; but they just ran up into the kitchen and Ingeborg, the cook, drove them down again; so nobody had a chance to search for them. Then Peter, Karsten and I were to hide. Peter and Karsten placed themselves in the big box-part of the mangle, and I put some sacks over them and there they were, beautifully hidden.

For myself, I thought of creeping into a cupboard in the brewery. But when it came to the point, I found that my legs had grown[Pg 88] so long since I last hid there that there wasn't room enough for them. I was at my wits' end. Any instant I expected Nils to whirl like a tempest into that room. I sprang into the wine cellar and looked about with a frantic glance. Only bare shelves, not a thing to hide one's self in. Oh, yes! There stood a meal chest. I lifted the lid—the chest was empty. Quick as a flash I jumped in and slammed the lid down.

There I lay. It was pretty close quarters but not so bad after all. Hurrah! What a first-rate hiding place! No one had ever before thought of hiding here.

I lay still, rejoicing over being so wonderfully well hidden. The minutes began to drag. At last I heard Karen and Antoinette running about and searching. Twice they were in the wine cellar.

"No—there is nobody here," they said. I kept still as a mouse, of course. Now they had found Peter and Karsten in the mangle box, for there was a great uproar out there.[Pg 89]

"But Inger Johanne! Where is Inger Johanne?"

"You'll be pretty smart if you find me!" I thought.

They ran about a while and rummaged in the brewery and then I heard them go out into the court. I lay still as a stone a little longer but it began to be somewhat warm in the meal chest, so I thought I would lift the lid a little. I pushed my back against it—but what in the world! It would not go up!

Once more I tried—and once more——Exactly what had happened I don't know, but there was a hook on the lid and when I hastily slammed the lid down, the hook probably dropped and caught on a nail in the meal chest itself.

In the first instant I can't say that I was terribly afraid. I kept on trying to get the lid up and all the time I thought, "They will soon come in here again to look for me and then I'll shout!"

But far from it. No one came. It was perfectly[Pg 90] silent. I heard nobody either in the brewery or out in the court or up in the kitchen. And all at once terror overwhelmed me,—terror at being shut up in that small place. It was as if I were in a grave. So I screamed, and banged on the lid, and kicked. Then I listened again. Not a sound was to be heard.

It was hot as fire in the meal chest. My face burned. How I screamed!

"Help me! I'm in the meal chest! help! oh, help!"

No, not a sound. What in the world would happen to me? I could scarcely get my breath—no—I knew I couldn't breathe any more. Yet again I shrieked. I cannot understand why nobody heard me. My breathing was short and difficult. No, I could not hold out—I surely could not breathe any more.

"Oh, Mother! Mother! Help me!"

Then I heard some one in the court and then footsteps in the brewery. I screamed again. Some one opened the door to the wine cellar and I heard Maren's voice.[Pg 91]

"What's that? What's that?"

"Maren, oh, Maren!" I called from the meal chest. Like a flash the door was shut again and I heard Maren running as fast as her legs could carry her up the kitchen stairs.

To think that she should run away without helping me! That seemed too sad and dreadful, when I was in such distress, and I cried and sobbed as hard as I could. And now I could scarcely get my breath again.

"Oh! oh! help, help!"

I could not scream any more, I was so strangely weak. Then I heard many feet in the kitchen above my head. They came nearer, and down the stairs, and then the door was opened. All I could do now was to call very faintly.

"Oh! Mother, Mother!"

At the same instant the lid of the meal chest was quickly thrown open. There stood Mother and Maren and Ingeborg, the cook. Mother lifted me out; I was crying so hard I could not say a word, nor explain at all how[Pg 92] it happened. However, a little while after I was as lively as ever.

"Oh, you ugly Maren—who wouldn't help me!"

"I thought it was a shriek from the underworld!" said Maren. "And I was so frightened! It clutched my heart. Oh! I shall never get over it." Maren sat on the corner of the potato bin and wept aloud.

Mother didn't know whether to scold Maren or to laugh at her. She behaved exactly as if it were she and not I who had been shut up in the meal chest.

Maren took surely a hundred Hofmann's drops and still she was poorly, and for many days she whimpered and whined about her fright at the meal chest. And even yet she cannot hear any mention of meal, or of a chest or of screaming, without her invariably saying:

"Yes, it's a wonder that I didn't get my death that time you were shut up in the meal chest—but I've had a swollen heart ever since then—and that I can thank you for."

But Mother says that's all nonsense.

One day a man from Vegassheien came into our kitchen with four live chickens that he wanted to sell. All hens, he said. We had never had any pets at our house except Bouncer, our big black cat; and Karsten and I were seized at once with an overwhelming desire to own these four half-grown, golden-brown chickens, who lay so patiently in the bottom of the peasant's basket, put their heads on one side and looked up at us with their little round black eyes. Oh, if Mother only would buy these darling chickens for us! It is such fun to have pets.

Speaking of pets makes me think of Uncle Ferdinand, and the pet monkey he had.