The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson - Swanston Edition Vol. 14 (of 25), by Robert Louis Stevenson This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Works of Robert Louis Stevenson - Swanston Edition Vol. 14 (of 25) Author: Robert Louis Stevenson Other: Andrew Lang Release Date: December 12, 2009 [EBook #30659] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WORKS OF R.L. STEVENSON V14 OF 25 *** Produced by Marius Masi, Jonathan Ingram and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Of this SWANSTON EDITION in Twenty-five

Volumes of the Works of ROBERT LOUIS

STEVENSON Two Thousand and Sixty Copies

have been printed, of which only Two Thousand

Copies are for sale.

This is No. ............

|

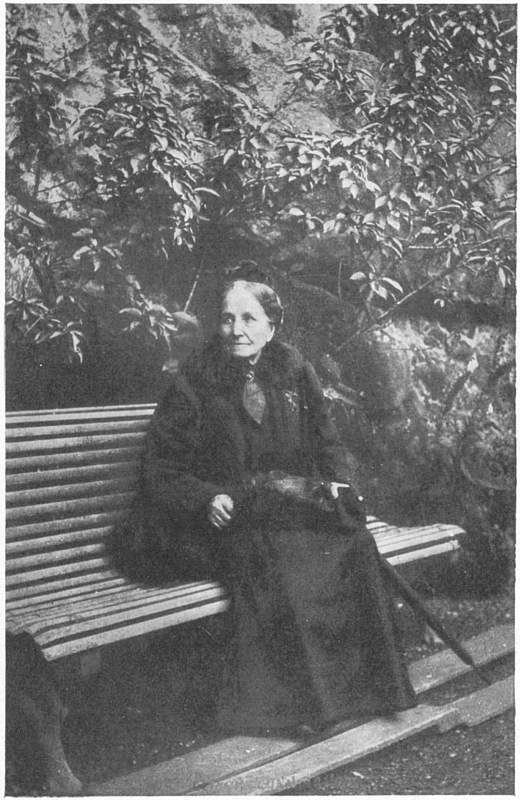

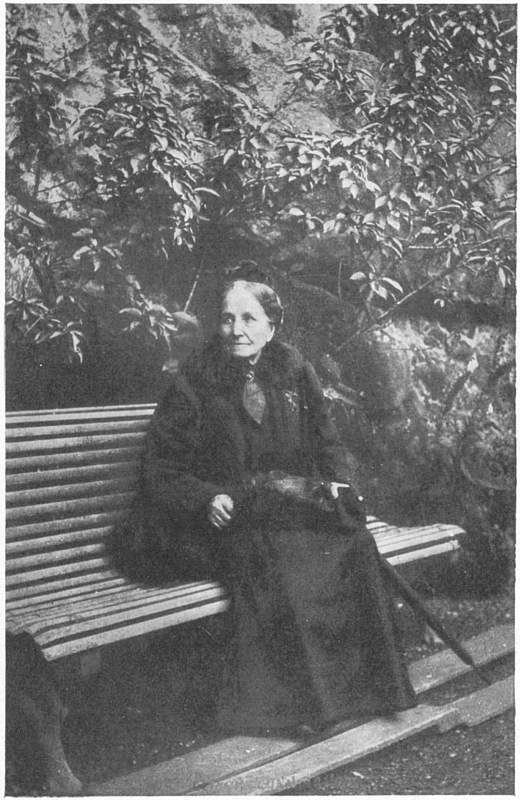

| ALISON CUNNINGHAM, R. L. S.’S NURSE |

| PAGE | ||

| I. | Bed in Summer In winter I get up at night |

3 |

| II. | A Thought It is very nice to think |

3 |

| III. | At the Sea-side When I was down beside the sea |

4 |

| IV. | Young Night Thought All night long, and every night |

4 |

| V. | Whole Duty of Children A child should always say what’s true |

5 |

| VI. | Rain The rain is raining all around |

5 |

| VII. | Pirate Story Three of us afloat in the meadow by the swing |

5 |

| VIII. | Foreign Lands Up into the cherry-tree |

6 |

| IX. | Windy Nights Whenever the moon and stars are set |

7 |

| X. | Travel I should like to rise and go |

7 |

| XI. | Singing Of speckled eggs the birdie sings |

9 |

| XII. | Looking Forward When I am grown to man’s estate |

9 |

| XIII. | A Good Play We built a ship upon the stairs |

9 |

| XIV. | Where go the Boats? Dark brown is the river |

10 |

| XV. | Auntie’s Skirts Whenever Auntie moves around |

11 |

| XVI. | The Land of Counterpane When I was sick and lay a-bed |

11 |

| XVII. | The Land of Nod From breakfast on all through the day |

12 |

| XVIII. | My Shadow I have a little shadow that goes in and out with me |

12 |

| XIX. | System Every night my prayers I say |

13 |

| XX. | A Good Boy I woke before the morning, I was happy all the day |

14 |

| XXI. | Escape at Bedtime The lights from the parlour and kitchen shone out |

14 |

| XXII. | Marching Song Bring the comb and play upon it |

15 |

| XXIII. | The Cow The friendly cow, all red and white |

16 |

| XXIV. | Happy Thought The world is so full of a number of things |

16 |

| XXV. | The Wind I saw you toss the kites on high |

16 |

| XXVI. | Keepsake Mill Over the borders, a sin without pardon |

17 |

| XXVII. | Good and Bad Children Children, you are very little |

18 |

| XXVIII. | Foreign Children Little Indian, Sioux or Crow |

19 |

| XXIX. | The Sun’s Travels The sun is not a-bed when I |

20 |

| XXX. | The Lamplighter My tea is nearly ready and the sun has left the sky |

20 |

| XXXI. | My Bed is a Boat My bed is like a little boat |

21 |

| XXXII. | The Moon The moon has a face like the clock in the hall |

22 |

| XXXIII. | The Swing How do you like to go up in a swing |

22 |

| XXXIV. | Time to Rise A birdie with a yellow bill |

23 |

| XXXV. | Looking-Glass River Smooth it slides upon its travel |

23 |

| XXXVI. | Fairy Bread Come up here, O dusty feet |

24 |

| XXXVII. | From a Railway Carriage Faster than fairies, faster than witches |

24 |

| XXXVIII. | Winter-Time Late lies the wintry sun a-bed |

25 |

| XXXIX. | The Hayloft Through all the pleasant meadow-side |

26 |

| XL. | Farewell to the Farm The coach is at the door at last |

26 |

| XLI. | North-West Passage | 27 |

| 1. Good Night When the bright lamp is carried in |

27 | |

| 2. Shadow March All round the house is the jet-black night |

28 | |

| 3. In Port Last, to the chamber where I lie |

28 | |

THE CHILD ALONE | ||

| I. | The Unseen Playmate When children are playing alone on the green |

31 |

| II. | My Ship and I O it’s I that am the captain of a tidy little ship |

32 |

| III. | My Kingdom Down by a shining water well |

32 |

| IV. | Picture-Books in Winter Summer fading, winter comes |

33 |

| V. | My Treasures These nuts, that I keep in the back of the nest |

34 |

| VI. | Block City What are you able to build with your blocks |

35 |

| VII. | The Land of Story-Books At evening when the lamp is lit |

36 |

| VIII. | Armies in the Fire The lamps now glitter down the street |

37 |

| IX. | The Little Land When at home alone I sit |

38 |

GARDEN DAYS | ||

| I. | Night and Day When the golden day is done |

43 |

| II. | Nest Eggs Birds all the sunny day |

44 |

| III. | The Flowers All the names I know from nurse |

46 |

| IV. | Summer Sun Great is the sun, and wide he goes |

46 |

| V. | The Dumb Soldier When the grass was closely mown |

47 |

| VI. | Autumn Fires In the other gardens |

49 |

| VII. | The Gardener The gardener does not love to talk |

49 |

| VIII. | Historical Associations Dear Uncle Jim, this garden ground |

50 |

ENVOYS | ||

| I. | To Willie and Henrietta If two may read aright |

55 |

| II. | To My Mother You too, my mother, read my rhymes |

55 |

| III. | To Auntie Chief of our aunts—not only I |

56 |

| IV. | To Minnie The red room with the giant bed |

56 |

| V. | To my Name-Child Some day soon this rhyming volume, if you learn with proper speed |

58 |

| VI. | To any Reader As from the house your mother sees |

59 |

UNDERWOODS | ||

BOOK I: IN ENGLISH | ||

| I. | Envoy Go, little book, and wish to all |

67 |

| II. | A Song of the Road The gauger walked with willing foot |

67 |

| III. | The Canoe Speaks On the great streams the ships may go |

68 |

| IV. | It is the season now to go |

70 |

| V. | The House Beautiful A naked house, a naked moor |

71 |

| VI. | A Visit From The Sea Far from the loud sea beaches |

72 |

| VII. | To a Gardener Friend, in my mountain-side demesne |

73 |

| VIII. | To Minnie A picture-frame for you to fill |

74 |

| IX. | To K. de M. A lover of the moorland bare |

74 |

| X. | To N. V. de G. S. The unfathomable sea, and time, and tears |

75 |

| XI. | To Will. H. Low Youth now flees on feathered foot |

76 |

| XII. | To Mrs. Will. H. Low Even in the bluest noonday of July |

77 |

| XIII. | To H. F. Brown I sit and wait a pair of oars |

78 |

| XIV. | To Andrew Lang Dear Andrew, with the brindled hair |

79 |

| XV. | Et tu in Arcadia vixisti (to r. a. m. s.) In ancient tales, O friend, thy spirit dwelt |

80 |

| XVI. | To W. E. Henley The year runs through her phases; rain and sun |

82 |

| XVII. | Henry James Who comes to-night? We ope the doors in vain |

83 |

| XVIII. | The Mirror Speaks Where the bells peal far at sea |

84 |

| XIX. | Katharine We see you as we see a face |

85 |

| XX. | To F. J. S. I read, dear friend, in your dear face |

85 |

| XXI. | Requiem Under the wide and starry sky |

86 |

| XXII. | The Celestial Surgeon If I have faltered more or less |

86 |

| XXIII. | Our Lady of the Snows Out of the sun, out of the blast |

87 |

| XXIV. | Not yet, my soul, these friendly fields desert |

89 |

| XXV. | It is not yours, O mother, to complain |

90 |

| XXVI. | The Sick Child O mother, lay your hand on my brow |

92 |

| XXVII. | In Memoriam F. A. S. Yet, O stricken heart, remember, O remember |

93 |

| XXVIII. | To my Father Peace and her huge invasion to these shores |

93 |

| XXIX. | In the States With half a heart I wander here |

94 |

| XXX. | A Portrait I am a kind of farthing dip |

95 |

| XXXI. | Sing clearlier, Muse, or evermore be still |

96 |

| XXXII. | A Camp The bed was made, the room was fit |

96 |

| XXXIII. | The Country of the Camisards We travelled in the print of olden wars |

96 |

| XXXIV. | Skerryvore For love of lovely words, and for the sake |

97 |

| XXXV. | Skerryvore: The Parallel Here all is sunny, and when the truant gull |

97 |

| XXXVI. | My house, I say. But hark to the sunny doves |

98 |

| XXXVII. | My body which my dungeon is |

98 |

| XXXVIII. | Say not of me that weakly I declined |

99 |

BOOK II: IN SCOTS | ||

| I. | The Maker to Posterity Far ’yont amang the years to be |

105 |

| II. | Ille Terrarum Frae nirly, nippin’, Eas’lan’ breeze |

106 |

| III. | When aince Aprile has fairly come |

109 |

| IV. | A Mile an’ a Bittock A mile an’ a bittock, a mile or twa |

110 |

| V. | A Lowden Sabbath Morn The clinkum-clank o’ Sabbath bells |

111 |

| VI. | The Spaewife O, I wad like to ken—to the beggar-wife says I |

116 |

| VII. | The Blast—1875 It’s rainin’. Weet’s the gairden sod |

116 |

| VIII. | The Counterblast—1886 My bonny man, the warld, it’s true |

118 |

| IX. | The Counterblast Ironical It’s strange that God should fash to frame |

120 |

| X. | Their Laureate to an Academy Class Dinner Club Dear Thamson class, whaure’er I gang |

121 |

| XI. | Embro Hie Kirk The Lord Himsel’ in former days |

123 |

| XII. | The Scotsman’s Return from Abroad In mony a foreign pairt I’ve been |

125 |

| XIII. | Late In the night in bed I lay |

129 |

| XIV. | My Conscience! Of a’ the ills that flesh can fear |

131 |

| XV. | To Dr. John Brown By Lyne and Tyne, by Thames and Tees |

133 |

| XVI. | It’s an owercome sooth for age an’ youth |

135 |

BALLADS | ||

THE SONG OF RAHÉRO | ||

A LEGEND OF TAHITI | ||

| I. | The Slaying of Támatéa | 139 |

| II. | The Venging Of Támatéa | 148 |

| III. | Rahéro | 159 |

THE FEAST OF FAMINE | ||

MARQUESAN MANNERS | ||

| I. | The Priest’s Vigil | 169 |

| II. | The Lovers | 172 |

| III. | The Feast | 176 |

| IV. | The Raid | 182 |

TICONDEROGA | ||

A LEGEND OF THE WEST HIGHLANDS | ||

| I. | The Saying of the Name | 189 |

| II. | The Seeking of the Name | 194 |

| III. | The Place of the Name | 196 |

HEATHER ALE | ||

A GALLOWAY LEGEND | ||

| From the bonny bells of heather | 201 | |

CHRISTMAS AT SEA | ||

| The sheets were frozen hard | 207 | |

| Notes to The Song of Rahéro | 211 | |

| Notes to The Feast of Famine | 213 | |

| Notes to Ticonderoga | 214 | |

| Note to Heather Ale | 215 | |

SONGS OF TRAVEL | ||

| I. | The Vagabond Give to me the life I love |

219 |

| II. | Youth and Love—I Once only by the garden gate |

220 |

| III. | Youth and Love—II To the heart of youth the world is a highwayside |

221 |

| IV. | In dreams, unhappy, I behold you stand |

221 |

| V. | She rested by the Broken Brook |

222 |

| VI. | The infinite shining heavens |

222 |

| VII. | Plain as the glistering planets shine |

223 |

| VIII. | To you, let snow and roses |

224 |

| IX. | Let Beauty awake in the morn from beautiful dreams |

224 |

| X. | I know not how it is with you |

225 |

| XI. | I will make you brooches and toys for your delight |

225 |

| XII. | We have loved of Yore Berried brake and reedy island |

226 |

| XIII. | Mater Triumphans Son of my woman’s body, you go, to the drum and fife |

227 |

| XIV. | Bright is the ring of words |

227 |

| XV. | In the highlands, in the country places |

228 |

| XVI. | Home no more home to me, whither must I wander |

229 |

| XVII. | Winter In rigorous hours, when down the iron lane |

230 |

| XVIII. | The stormy evening closes now in vain |

230 |

| XIX. | To Dr. Hake In the beloved hour that ushers day |

231 |

| XX. | To —— I knew thee strong and quiet like the hills |

232 |

| XXI. | The morning drum-call on my eager ear |

233 |

| XXII. | I have trod the upward and the downward slope |

233 |

| XXIII. | He hears with gladdened heart the thunder |

233 |

| XXIV. | Farewell, fair day and fading light |

233 |

| XXV. | If this were Faith God, if this were enough |

234 |

| XXVI. | My Wife Trusty, dusky, vivid, true |

235 |

| XXVII. | To the Muse Resign the rhapsody, the dream |

236 |

| XXVIII. | To an Island Princess Since long ago, a child at home |

237 |

| XXIX. | To Kalakaua The Silver Ship, my King—that was her name |

238 |

| XXX. | To Princess Kaiulani Forth from her land to mine she goes |

239 |

| XXXI. | To Mother Maryanne To see the infinite pity of this place |

240 |

| XXXII. | In Memoriam E. H. I knew a silver head was bright beyond compare |

240 |

| XXXIII. | To my Wife Long must elapse ere you behold again |

241 |

| XXXIV. | To my old Familiars Do you remember—can we e’er forget |

242 |

| XXXV. | The tropics vanish, and meseems that I |

243 |

| XXXVI. | To S. C. I heard the pulse of the besieging sea |

244 |

| XXXVII. | The House of Tembinoka Let us, who part like brothers, part like bards |

245 |

| XXXVIII. | The Woodman In all the grove, nor stream nor bird |

249 |

| XXXIX. | Tropic Rain As the single pang of the blow, when the metal is mingled well |

254 |

| XL. | An End of Travel Let now your soul in this substantial world |

255 |

| XLI. | We uncommiserate pass into the night |

255 |

| XLII. | Sing me a song of a lad that is gone |

256 |

| XLIII. | To S. R. Crockett Blows the wind to-day, and the sun and the rain are flying |

257 |

| XLIV. | Evensong The embers of the day are red |

257 |

ADDITIONAL POEMS | ||

| I. | A Familiar Epistle Blame me not that this epistle |

261 |

| II. | Rondels 1. Far have you come, my lady, from the town 2. Nous n’irons plus au bois 3. Since I am sworn to live my life 4. Of his pitiable transformation |

263 |

| III. | Epistle to Charles Baxter Noo lyart leaves blaw ower the green |

265 |

| IV. | The Susquehannah and the Delaware Of where or how, I nothing know |

267 |

| V. | Epistle to Albert Dew-Smith Figure me to yourself, I pray |

268 |

| VI. | Alcaics to Horatio F. Brown Brave lads in olden musical centuries |

270 |

| VII. | A Lytle Jape of Tusherie The pleasant river gushes |

272 |

| VIII. | To Virgil and Dora Williams Here, from the forelands of the tideless sea |

273 |

| IX. | Burlesque Sonnet Thee, Mackintosh, artificer of light |

273 |

| X. | The Fine Pacific Islands The jolly English Yellowboy |

274 |

| XI. | Auld Reekie When chitterin’ cauld the day sall daw |

275 |

| XII. | The Lesson of the Master Adela, Adela, Adela Chart |

276 |

| XIII. | The Consecration of Braille I was a barren tree before |

276 |

| XIV. | Song Light foot and tight foot |

277 |

|

For the long nights you lay awake And watched for my unworthy sake: For your most comfortable hand That led me through the uneven land: For all the story-books you read: For all the pains you comforted: For all you pitied, all you bore, In sad and happy days of yore:— My second Mother, my first Wife, The angel of my infant life— From the sick child, now well and old, Take, nurse, the little book you hold! And grant it, Heaven, that all who read May find as dear a nurse at need, And every child who lists my rhyme, In the bright, fireside, nursery clime, May hear it in as kind a voice As made my childish days rejoice! |

R. L. S.

|

In winter I get up at night And dress by yellow candle-light. In summer, quite the other way,— I have to go to bed by day. I have to go to bed and see The birds still hopping on the tree, Or hear the grown-up people’s feet Still going past me in the street. And does it not seem hard to you, When all the sky is clear and blue, And I should like so much to play, To have to go to bed by day? |

|

It is very nice to think The world is full of meat and drink, With little children saying grace In every Christian kind of place. |

|

When I was down beside the sea, A wooden spade they gave to me To dig the sandy shore. My holes were empty like a cup, In every hole the sea came up, Till it could come no more. |

|

All night long, and every night, When my mamma puts out the light, I see the people marching by, As plain as day, before my eye. Armies and emperors and kings, All carrying different kinds of things, And marching in so grand a way, You never saw the like by day. So fine a show was never seen At the great circus on the green; For every kind of beast and man Is marching in that caravan. At first they move a little slow, But still the faster on they go, And still beside them close I keep Until we reach the town of Sleep. |

|

A child should always say what’s true, And speak when he is spoken to, And behave mannerly at table: At least as far as he is able. |

|

The rain is raining all around, It falls on field and tree, It rains on the umbrellas here, And on the ships at sea. |

|

Three of us afloat in the meadow by the swing, Three of us aboard in the basket on the lea. Winds are in the air, they are blowing in the spring, And waves are on the meadow like the waves there are at sea. Where shall we adventure, to-day that we’re afloat, Wary of the weather, and steering by a star? Shall it be to Africa, a-steering of the boat, To Providence, or Babylon, or off to Malabar? Hi! but here’s a squadron a-rowing on the sea— Cattle on the meadow a-charging with a roar! Quick, and we’ll escape them, they’re as mad as they can be, The wicket is the harbour and the garden is the shore. |

|

Up into the cherry-tree Who should climb but little me? I held the trunk with both my hands And looked abroad on foreign lands. I saw the next-door garden lie, Adorned with flowers, before my eye, And many pleasant places more That I had never seen before. I saw the dimpling river pass And be the sky’s blue looking-glass; The dusty roads go up and down With people tramping in to town. If I could find a higher tree, Farther and farther I should see To where the grown-up river slips Into the sea among the ships, To where the roads on either hand Lead onward into fairy-land, Where all the children dine at five, And all the playthings come alive. |

|

Whenever the moon and stars are set, Whenever the wind is high, All night long in the dark and wet, A man goes riding by. Late in the night when the fires are out, Why does he gallop and gallop about? Whenever the trees are crying aloud, And ships are tossed at sea, By, on the highway, low and loud, By at the gallop goes he. By at the gallop he goes, and then By he comes back at the gallop again. |

|

I should like to rise and go Where the golden apples grow;— Where below another sky Parrot islands anchored lie, And, watched by cockatoos and goats, Lonely Crusoes building boats;— Where in sunshine reaching out Eastern cities, miles about, Are with mosque and minaret Among sandy gardens set, And the rich goods from near and far Hang for sale in the bazaar;— Where the Great Wall round China goes, And on one side the desert blows, And with bell and voice and drum, Cities on the other hum;— Where are forests, hot as fire, Wide as England, tall as a spire, Full of apes and cocoa-nuts And the negro hunters’ huts;— Where the knotty crocodile Lies and blinks in the Nile, And the red flamingo flies Hunting fish before his eyes;— Where in jungles, near and far, Man-devouring tigers are, Lying close and giving ear Lest the hunt be drawing near, Or a comer-by be seen Swinging in a palanquin;— Where among the desert sands Some deserted city stands, All its children, sweep and prince, Grown to manhood ages since, Not a foot in street or house, Nor a stir of child or mouse, And when kindly falls the night, In all the town no spark of light. There I’ll come when I’m a man With a camel caravan; Light a fire in the gloom Of some dusty dining-room; See the pictures on the walls, Heroes, fights, and festivals; And in a corner find the toys Of the old Egyptian boys. |

|

Of speckled eggs the birdie sings And nests among the trees; The sailor sings of ropes and things In ships upon the seas. The children sing in far Japan, The children sing in Spain; The organ with the organ man Is singing in the rain. |

|

When I am grown to man’s estate I shall be very proud and great, And tell the other girls and boys Not to meddle with my toys. |

|

We built a ship upon the stairs All made of the back-bedroom chairs And filled it full of sofa pillows To go a-sailing on the billows. We took a saw and several nails, And water in the nursery pails; And Tom said, “Let us also take An apple and a slice of cake”;— Which was enough for Tom and me To go a-sailing on, till tea. We sailed along for days and days, And had the very best of plays; But Tom fell out and hurt his knee, So there was no one left but me. |

|

Dark brown is the river, Golden is the sand. It flows along for ever, With trees on either hand. Green leaves a-floating, Castles of the foam, Boats of mine a-boating— Where will all come home? On goes the river, And out past the mill, Away down the valley, Away down the hill. Away down the river, A hundred miles or more, Other little children Shall bring my boats ashore. |

|

Whenever Auntie moves around, Her dresses make a curious sound; They trail behind her up the floor, And trundle after through the door. |

|

When I was sick and lay a-bed, I had two pillows at my head, And all my toys beside me lay To keep me happy all the day. And sometimes for an hour or so I watched my leaden soldiers go, With different uniforms and drills, Among the bed-clothes, through the hills; And sometimes sent my ships in fleets All up and down among the sheets; Or brought my trees and houses out, And planted cities all about. I was the giant great and still That sits upon the pillow-hill, And sees before him, dale and plain, The pleasant land of counterpane. |

|

From breakfast on all through the day At home among my friends I stay; But every night I go abroad Afar into the land of Nod. All by myself I have to go, With none to tell me what to do— All alone beside the streams And up the mountain-sides of dreams. The strangest things are there for me, Both things to eat and things to see, And many frightening sights abroad Till morning in the land of Nod. Try as I like to find the way, I never can get back by day, Nor can remember plain and clear The curious music that I hear. |

|

I have a little shadow that goes in and out with me, And what can be the use of him is more than I can see. He is very, very like me from the heels up to the head; And I see him jump before me, when I jump into my bed. The funniest thing about him is the way he likes to grow— Not at all like proper children, which is always very slow; For he sometimes shoots up taller like an india-rubber ball, And he sometimes gets so little that there’s none of him at all. He hasn’t got a notion of how children ought to play, And can only make a fool of me in every sort of way. He stays so close beside me, he’s a coward you can see; I’d think shame to stick to nursie as that shadow sticks to me! One morning, very early, before the sun was up, I rose and found the shining dew on every buttercup; But my lazy little shadow, like an arrant sleepy-head, Had stayed at home behind me and was fast asleep in bed. |

|

Every night my prayers I say, And get my dinner every day; And every day that I’ve been good, I get an orange after food. The child that is not clean and neat, With lots of toys and things to eat, He is a naughty child, I’m sure— Or else his dear papa is poor. |

|

I woke before the morning, I was happy all the day, I never said an ugly word, but smiled and stuck to play. And now at last the sun is going down behind the wood, And I am very happy, for I know that I’ve been good. My bed is waiting cool and fresh, with linen smooth and fair, And I must off to sleepsin-by, and not forget my prayer. I know that, till to-morrow I shall see the sun arise, No ugly dream shall fright my mind, no ugly sight my eyes, But slumber hold me tightly till I waken in the dawn, And hear the thrushes singing in the lilacs round the lawn. |

|

The lights from the parlour and kitchen shone out Through the blinds and the windows and bars; And high overhead and all moving about, There were thousands of millions of stars. There ne’er were such thousands of leaves on a tree, Nor of people in church or the Park, As the crowds of the stars that looked down upon me, And that glittered and winked in the dark. The Dog, and the Plough, and the Hunter, and all, And the star of the sailor, and Mars, These shone in the sky, and the pail by the wall Would be half full of water and stars. They saw me at last, and they chased me with cries, And they soon had me packed into bed; But the glory kept shining and bright in my eyes, And the stars going round in my head. |

|

Bring the comb and play upon it! Marching, here we come! Willie cocks his Highland bonnet, Johnnie beats the drum. Mary Jane commands the party, Peter leads the rear; Feet in time, alert and hearty, Each a Grenadier! All in the most martial manner Marching double-quick; While the napkin like a banner Waves upon the stick! Here’s enough of fame and pillage, Great commander Jane! Now that we’ve been round the village, Let’s go home again. |

|

The friendly cow, all red and white, I love with all my heart: She gives me cream with all her might, To eat with apple-tart. She wanders lowing here and there, And yet she cannot stray, All in the pleasant open air, The pleasant light of day; And blown by all the winds that pass, And wet with all the showers, She walks among the meadow grass And eats the meadow flowers. |

|

The world is so full of a number of things, I’m sure we should all be as happy as kings. |

|

I saw you toss the kites on high And blow the birds about the sky; And all around I heard you pass, Like ladies’ skirts across the grass— O wind, a-blowing all day long, O wind, that sings so loud a song! I saw the different things you did, But always you yourself you hid. I felt you push, I heard you call, I could not see yourself at all— O wind, a-blowing all day long, O wind, that sings so loud a song! O you that are so strong and cold, O blower, are you young or old? Are you a beast of field and tree, Or just a stronger child than me? O wind, a-blowing all day long, O wind, that sings so loud a song! |

|

Over the borders, a sin without pardon, Breaking the branches and crawling below, Out through the breach in the wall of the garden, Down by the banks of the river, we go. Here is the mill with the humming of thunder, Here is the weir with the wonder of foam, Here is the sluice with the race running under— Marvellous places, though handy to home! Sounds of the village grow stiller and stiller, Stiller the note of the birds on the hill; Dusty and dim are the eyes of the miller, Deaf are his ears with the moil of the mill. Years may go by, and the wheel in the river, Wheel as it wheels for us, children, to-day, Wheel and keep roaring and foaming for ever, Long after all of the boys are away. Home from the Indies, and home from the ocean, Heroes and soldiers we all shall come home; Still we shall find the old mill-wheel in motion, Turning and churning that river to foam. You with the bean that I gave when we quarrelled, I with your marble of Saturday last, Honoured and old and all gaily apparelled, Here we shall meet and remember the past. |

|

Children, you are very little, And your bones are very brittle; If you would grow great and stately, You must try to walk sedately. You must still be bright and quiet, And content with simple diet; And remain, through all bewild’ring, Innocent and honest children. Happy hearts and happy faces, Happy play in grassy places— That was how, in ancient ages, Children grew to kings and sages. But the unkind and the unruly, And the sort who eat unduly, They must never hope for glory— Theirs is quite a different story! Cruel children, crying babies, All grow up as geese and gabies, Hated, as their age increases, By their nephews and their nieces. |

|

Little Indian, Sioux or Crow, Little frosty Eskimo, Little Turk or Japanee, O! don’t you wish that you were me? You have seen the scarlet trees And the lions over seas; You have eaten ostrich eggs, And turned the turtles off their legs. Such a life is very fine, But it’s not so nice as mine; You must often, as you trod, Have wearied not to be abroad. You have curious things to eat, I am fed on proper meat; You must dwell beyond the foam, But I am safe and live at home. Little Indian, Sioux or Crow Little frosty Eskimo, Little Turk or Japanee, O! don’t you wish that you were me? |

|

The sun is not a-bed when I At night upon my pillow lie; Still round the earth his way he takes, And morning after morning makes. While here at home, in shining day, We round the sunny garden play, Each little Indian sleepy-head Is being kissed and put to bed. And when at eve I rise from tea, Day dawns beyond the Atlantic Sea, And all the children in the West Are getting up and being dressed. |

|

My tea is nearly ready and the sun has left the sky; It’s time to take the window to see Leerie going by; For every night at tea-time and before you take your seat, With lantern and with ladder he comes posting up the street. Now Tom would be a driver and Maria go to sea, And my papa’s a banker and as rich as he can be; But I, when I am stronger, and can choose what I’m to do, O Leerie, I’ll go round at night and light the lamps with you! For we are very lucky, with a lamp before the door, And Leerie stops to light it as he lights so many more; And O! before you hurry by with ladder and with light, O Leerie, see a little child and nod to him to-night! |

|

My bed is like a little boat; Nurse helps me in when I embark; She girds me in my sailor’s coat And starts me in the dark. At night, I go on board and say Good-night to all my friends on shore; I shut my eyes and sail away And see and hear no more. And sometimes things to bed I take, As prudent sailors have to do: Perhaps a slice of wedding-cake, Perhaps a toy or two. All night across the dark we steer: But when the day returns at last, Safe in my room, beside the pier, I find my vessel fast. |

|

The moon has a face like the clock in the hall; She shines on thieves on the garden wall, On streets and fields and harbour quays, And birdies asleep in the forks of the trees. The squalling cat and the squeaking mouse, The howling dog by the door of the house, The bat that lies in bed at noon, All love to be out by the light of the moon. But all of the things that belong to the day Cuddle to sleep to be out of her way; And flowers and children close their eyes Till up in the morning the sun shall arise. |

|

How do you like to go up in a swing, Up in the air so blue? Oh, I do think it the pleasantest thing Ever a child can do! Up in the air and over the wall, Till I can see so wide, Rivers and trees and cattle and all Over the countryside— Till I look down on the garden green, Down on the roof so brown— Up in the air I go flying again, Up in the air and down! |

|

A birdie with a yellow bill Hopped upon the window sill, Cocked his shining eye and said: “Ain’t you ’shamed, you sleepy-head?” |

|

Smooth it slides upon its travel, Here a wimple, there a gleam— O the clean gravel! O the smooth stream! Sailing blossoms, silver fishes, Paven pools as clear as air— How a child wishes To live down there! We can see our coloured faces Floating on the shaken pool Down in cool places, Dim and very cool; Till a wind or water wrinkle, Dipping marten, plumping trout, Spreads in a twinkle And blots all out. See the rings pursue each other; All below grows black as night, Just as if mother Had blown out the light! Patience, children, just a minute— See the spreading circles die; The stream and all in it Will clear by-and-by. |

|

Come up here, O dusty feet! Here is fairy bread to eat. Here in my retiring room, Children, you may dine On the golden smell of broom And the shade of pine; And when you have eaten well, Fairy stories hear and tell. |

|

Faster than fairies, faster than witches, Bridges and houses, hedges and ditches; And charging along like troops in a battle, All through the meadows the horses and cattle: All of the sights of the hill and the plain Fly as thick as driving rain; And ever again, in the wink of an eye, Painted stations whistle by. Here is a child who clambers and scrambles, All by himself and gathering brambles; Here is a tramp who stands and gazes; And there is the green for stringing the daisies! Here is a cart run away in the road Lumping along with man and load; And here is a mill, and there is a river: Each a glimpse and gone for ever! |

|

Late lies the wintry sun a-bed, A frosty, fiery sleepy-head; Blinks but an hour or two; and then, A blood-red orange, sets again. Before the stars have left the skies, At morning in the dark I rise; And shivering in my nakedness, By the cold candle, bathe and dress. Close by the jolly fire I sit To warm my frozen bones a bit; Or with a reindeer-sled explore The colder countries round the door. When, to go out, my nurse doth wrap Me in my comforter and cap, The cold wind burns my face, and blows Its frosty pepper up my nose. Black are my steps on silver sod; Thick blows my frosty breath abroad; And tree and house, and hill and lake, Are frosted like a wedding-cake. |

|

Through all the pleasant meadow-side The grass grew shoulder-high, Till the shining scythes went far and wide And cut it down to dry. These green and sweetly smelling crops They led in waggons home; And they piled them here in mountain tops For mountaineers to roam. Here is Mount Clear, Mount Rusty-Nail, Mount Eagle and Mount High;— The mice that in these mountains dwell No happier are than I! O what a joy to clamber there, O what a place for play, With the sweet, the dim, the dusty air, The happy hills of hay. |

|

The coach is at the door at last; The eager children, mounting fast And kissing hands, in chorus sing: Good-bye, good-bye, to everything! To house and garden, field and lawn, The meadow-gates we swang upon, To pump and stable, tree and swing, Good-bye, good-bye, to everything! And fare you well for evermore, O ladder at the hayloft door, O hayloft where the cobwebs cling, Good-bye, good-bye, to everything! Crack goes the whip, and off we go; The trees and houses smaller grow; Last, round the woody turn we swing: Good-bye, good-bye, to everything! |

|

When the bright lamp is carried in, The sunless hours again begin; O’er all without, in field and lane, The haunted night returns again. Now we behold the embers flee About the firelit hearth; and see Our faces painted as we pass, Like pictures, on the window-glass. Must we to bed indeed? Well then, Let us arise and go like men, And face with an undaunted tread The long black passage up to bed. Farewell, O brother, sister, sire! O pleasant party round the fire! The songs you sing, the tales you tell, Till far to-morrow, fare ye well! |

|

All round the house is the jet-black night; It stares through the window-pane; It crawls in the corners, hiding from the light, And it moves with the moving flame. Now my little heart goes a-beating like a drum, With the breath of the Bogie in my hair; And all round the candle the crooked shadows come And go marching along up the stair. The shadow of the balusters, the shadow of the lamp, The shadow of the child that goes to bed— All the wicked shadows coming, tramp, tramp, tramp, With the black night overhead. |

|

Last, to the chamber where I lie My fearful footsteps patter nigh, And come from out the cold and gloom Into my warm and cheerful room. There, safe arrived, we turned about To keep the coming shadows out, And close the happy door at last On all the perils that we passed. Then, when mamma goes by to bed, She shall come in with tip-toe tread, And see me lying warm and fast And in the land of Nod at last. |

|

When children are playing alone on the green, In comes the playmate that never was seen. When children are happy and lonely and good, The Friend of the Children comes out of the wood. Nobody heard him and nobody saw, His is a picture you never could draw, But he’s sure to be present, abroad or at home, When children are happy and playing alone. He lies in the laurels, he runs on the grass, He sings when you tinkle the musical glass; Whene’er you are happy and cannot tell why, The Friend of the Children is sure to be by! He loves to be little, he hates to be big, ’Tis he that inhabits the caves that you dig; ’Tis he when you play with your soldiers of tin That sides with the Frenchmen and never can win. ’Tis he, when at night you go off to your bed, Bids you go to your sleep and not trouble your head; For wherever they’re lying, in cupboard or shelf, ’Tis he will take care of your playthings himself! |

|

O it’s I that am the captain of a tidy little ship, Of a ship that goes a-sailing on the pond; And my ship it keeps a-turning all around and all about; But when I’m a little older, I shall find the secret out How to send my vessel sailing on beyond. For I mean to grow as little as the dolly at the helm, And the dolly I intend to come alive; And with him beside to help me, it’s a-sailing I shall go, It’s a-sailing on the water, when the jolly breezes blow And the vessel goes a divie-divie-dive. O it’s then you’ll see me sailing through the rushes and the reeds, And you’ll hear the water singing at the prow; For beside the dolly sailor, I’m to voyage and explore, To land upon the island where no dolly was before, And to fire the penny cannon in the bow. |

|

Down by a shining water well I found a very little dell, No higher than my head. The heather and the gorse about In summer bloom were coming out, Some yellow and some red. I called the little pool a sea; The little hills were big to me; For I am very small. I made a boat, I made a town, I searched the caverns up and down, And named them one and all. And all about was mine, I said, The little sparrows overhead, The little minnows too. This was the world, and I was king; For me the bees came by to sing, For me the swallows flew. I played there were no deeper seas, Nor any wider plains than these, Nor other kings than me. At last I heard my mother call Out from the house at even-fall, To call me home to tea. And I must rise and leave my dell, And leave my dimpled water well, And leave my heather blooms. Alas! and as my home I neared, How very big my nurse appeared, How great and cool the rooms! |

|

Summer fading, winter comes— Frosty mornings, tingling thumbs, Window robins, winter rooks, And the picture story-books. Water now is turned to stone Nurse and I can walk upon; Still we find the flowing brooks In the picture story-books. All the pretty things put by Wait upon the children’s eye, Sheep and shepherds, trees and crooks, In the picture story-books. We may see how all things are, Seas and cities, near and far, And the flying fairies’ looks, In the picture story-books. How am I to sing your praise, Happy chimney-corner days, Sitting safe in nursery nooks, Reading picture story-books? |

|

These nuts, that I keep in the back of the nest Where all my lead soldiers are lying at rest, Were gathered in autumn by nursie and me In a wood with a well by the side of the sea. This whistle we made (and how clearly it sounds!) By the side of a field at the end of the grounds. Of a branch of a plane, with a knife of my own, It was nursie who made it, and nursie alone! The stone, with the white and the yellow and grey, We discovered I cannot tell how far away; And I carried it back, although weary and cold, For, though father denies it, I’m sure it is gold. But of all of my treasures the last is the king, For there’s very few children possess such a thing; And that is a chisel, both handle and blade, Which a man who was really a carpenter made. |

|

What are you able to build with your blocks? Castles and palaces, temples and docks. Rain may keep raining, and others go roam, But I can be happy and building at home. Let the sofa be mountains, the carpet be sea, There I’ll establish a city for me: A kirk and a mill and a palace beside, And a harbour as well where my vessels may ride. Great is the palace with pillar and wall, A sort of a tower on the top of it all, And steps coming down in an orderly way To where my toy vessels lie safe in the bay. This one is sailing and that one is moored: Hark to the song of the sailors on board! And see, on the steps of my palace, the kings Coming and going with presents and things! Now I have done with it, down let it go! All in a moment the town is laid low. Block upon block lying scattered and free, What is there left of my town by the sea? Yet, as I saw it, I see it again, The kirk and the palace, the ships and the men, And as long as I live, and where’er I may be, I’ll always remember my town by the sea. |

|

At evening when the lamp is lit, Around the fire my parents sit; They sit at home and talk and sing, And do not play at anything. Now, with my little gun, I crawl All in the dark along the wall, And follow round the forest track Away behind the sofa back. There, in the night, where none can spy, All in my hunter’s camp I lie, And play at books that I have read Till it is time to go to bed. These are the hills, these are the woods, These are my starry solitudes; And there the river by whose brink The roaring lions come to drink. I see the others far away As if in firelit camp they lay, And I, like to an Indian scout, Around their party prowled about So, when my nurse comes in for me, Home I return across the sea, And go to bed with backward looks At my dear land of Story-books. |

|

The lamps now glitter down the street; Faintly sound the falling feet; And the blue even slowly falls About the garden trees and walls. Now in the falling of the gloom The red fire paints the empty room: And warmly on the roof it looks, And flickers on the backs of books. Armies march by tower and spire Of cities blazing, in the fire;— Till as I gaze with staring eyes, The armies fade, the lustre dies. Then once again the glow returns; Again the phantom city burns; And down the red-hot valley, lo! The phantom armies marching go! Blinking embers, tell me true Where are those armies marching to, And what the burning city is That crumbles in your furnaces! |

|

When at home alone I sit And am very tired of it, I have just to shut my eyes To go sailing through the skies— To go sailing far away To the pleasant Land of Play; To the fairy land afar Where the Little People are; Where the clover-tops are trees, And the rain-pools are the seas, And the leaves like little ships Sail about on tiny trips; And above the daisy tree Through the grasses, High o’erhead the Bumble Bee Hums and passes. In that forest to and fro I can wander, I can go; See the spider and the fly, And the ants go marching by Carrying parcels with their feet Down the green and grassy street. I can in the sorrel sit Where the ladybird alit. I can climb the jointed grass; And on high See the greater swallows pass In the sky, And the round sun rolling by Heeding no such things as I. Through that forest I can pass Till, as in a looking-glass, Humming fly and daisy tree And my tiny self I see Painted very clear and neat On the rain-pool at my feet. Should a leaflet come to land Drifting near to where I stand, Straight I’ll board that tiny boat Round the rain-pool sea to float. Little thoughtful creatures sit On the grassy coasts of it; Little things with lovely eyes See me sailing with surprise. Some are clad in armour green— (These have sure to battle been!)— Some are pied with ev’ry hue, Black and crimson, gold and blue; Some have wings and swift are gone;— But they all look kindly on. When my eyes I once again Open and see all things plain; High bare walls, great bare floor; Great big knobs on drawer and door; Great big people perched on chairs, Stitching tucks and mending tears, Each a hill that I could climb, And talking nonsense all the time— O dear me, That I could be A sailor on the rain-pool sea, A climber in the clover-tree, And just come back, a sleepy-head, Late at night to go to bed. |

|

When the golden day is done, Through the closing portal, Child and garden, flower and sun, Vanish all things mortal. As the blinding shadows fall, As the rays diminish, Under evening’s cloak, they all Roll away and vanish. Garden darkened, daisy shut, Child in bed, they slumber— Glow-worm in the highway rut, Mice among the lumber. In the darkness houses shine, Parents move with candles; Till on all the night divine Turns the bedroom handles. Till at last the day begins In the east a-breaking, In the hedges and the whins Sleeping birds a-waking. In the darkness shapes of things, Houses, trees, and hedges, Clearer grow; and sparrows’ wings Beat on window ledges. These shall wake the yawning maid; She the door shall open— Finding dew on garden glade And the morning broken. There my garden grows again Green and rosy painted, As at eve behind the pane From my eyes it fainted. Just as it was shut away, Toy-like, in the even, Here I see it glow with day Under glowing heaven. Every path and every plot, Every bush of roses, Every blue forget-me-not Where the dew reposes, “Up!” they cry, “the day is come On the smiling valleys: We have beat the morning drum; Playmate, join your allies!” |

|

Birds all the sunny day Flutter and quarrel, Here in the arbour-like Tent of the laurel. Here in the fork The brown nest is seated; Four little blue eggs The mother keeps heated. While we stand watching her, Staring like gabies, Safe in each egg are the Bird’s little babies. Soon the frail eggs they shall Chip, and upspringing Make all the April woods Merry with singing. Younger than we are, O children, and frailer, Soon in blue air they’ll be, Singer and sailor. We, so much older, Taller and stronger, We shall look down on the Birdies no longer. They shall go flying With musical speeches High overhead in the Tops of the beeches. In spite of our wisdom And sensible talking, We on our feet must go Plodding and walking. |

|

All the names I know from nurse: Gardener’s garters, Shepherd’s purse, Bachelor’s buttons, Lady’s smock, And the Lady Hollyhock. Fairy places, fairy things, Fairy woods where the wild bee wings, Tiny trees for tiny dames— These must all be fairy names! Tiny woods below whose boughs Shady fairies weave a house; Tiny tree-tops, rose or thyme, Where the braver fairies climb! Fair are grown-up people’s trees, But the fairest woods are these; Where if I were not so tall, I should live for good and all. |

|

Great is the sun, and wide he goes Through empty heaven without repose; And in the blue and glowing days More thick than rain he showers his rays. Though closer still the blinds we pull To keep the shady parlour cool, Yet he will find a chink or two To slip his golden fingers through. The dusty attic, spider-clad, He, through the keyhole, maketh glad; And through the broken edge of tiles Into the laddered hayloft smiles. Meantime his golden face around He bares to all the garden ground, And sheds a warm and glittering look Among the ivy’s inmost nook. Above the hills, along the blue, Round the bright air with footing true, To please the child, to paint the rose, The gardener of the World, he goes. |

|

When the grass was closely mown, Walking on the lawn alone, In the turf a hole I found And hid a soldier underground. Spring and daisies came apace; Grasses hide my hiding-place; Grasses run like a green sea O’er the lawn up to my knee. Under grass alone he lies, Looking up with leaden eyes, Scarlet coat and pointed gun, To the stars and to the sun. When the grass is ripe like grain, When the scythe is stoned again, When the lawn is shaven clear, Then my hole shall reappear. I shall find him, never fear, I shall find my grenadier; But, for all that’s gone and come, I shall find my soldier dumb. He has lived, a little thing, In the grassy woods of spring; Done, if he could tell me true, Just as I should like to do. He has seen the starry hours And the springing of the flowers; And the fairy things that pass In the forests of the grass. In the silence he has heard Talking bee and ladybird, And the butterfly has flown O’er him as he lay alone. Not a word will he disclose, Not a word of all he knows. I must lay him on the shelf, And make up the tale myself. |

|

In the other gardens And all up the vale, From the autumn bonfires See the smoke trail! Pleasant summer over, And all the summer flowers, The red fire blazes, The grey smoke towers. Sing a song of seasons! Something bright in all! Flowers in the summer, Fires in the fall! |

|

The gardener does not love to talk, He makes me keep the gravel walk; And when he puts his tools away, He locks the door and takes the key. Away behind the currant row Where no one else but cook may go, Far in the plots, I see him dig, Old and serious, brown and big. He digs the flowers, green, red, and blue, Nor wishes to be spoken to. He digs the flowers and cuts the hay, And never seems to want to play. Silly gardener! summer goes, And winter comes with pinching toes, When in the garden bare and brown You must lay your barrow down. Well now, and while the summer stays, To profit by these garden days, O how much wiser you would be To play at Indian wars with me! |

|

Dear Uncle Jim, this garden ground, That now you smoke your pipe around, Has seen immortal actions done And valiant battles lost and won. Here we had best on tip-toe tread, While I for safety march ahead, For this is that enchanted ground Where all who loiter slumber sound. Here is the sea, here is the sand, Here is simple Shepherd’s Land, Here are the fairy hollyhocks, And there are Ali Baba’s rocks. But yonder, see! apart and high, Frozen Siberia lies; where I, With Robert Bruce and William Tell, Was bound by an enchanter’s spell. There, then, a while in chains we lay, In wintry dungeons, far from day; But ris’n at length, with might and main, Our iron fetters burst in twain. Then all the horns were blown in town; And, to the ramparts clanging down, All the giants leaped to horse And charged behind us through the gorse. On we rode, the others and I, Over the mountains blue, and by The Silver River, the sounding sea, And the robber woods of Tartary. A thousand miles we galloped fast, And down the witches’ lane we passed, And rode amain, with brandished sword, Up to the middle, through the ford. Last we drew rein—a weary three— Upon the lawn, in time for tea, And from our steeds alighted down Before the gates of Babylon. |

|

If two may read aright These rhymes of old delight And house and garden play, You two, my cousins, and you only, may. You in a garden green With me were king and queen, Were hunter, soldier, tar, And all the thousand things that children are. Now in the elders’ seat We rest with quiet feet, And from the window-bay We watch the children, our successors, play. “Time was,” the golden head Irrevocably said; But time which none can bind, While flowing fast away, leaves love behind. |

|

You too, my mother, read my rhymes For love of unforgotten times, And you may chance to hear once more The little feet along the floor. |

|

Chief of our aunts—not only I, But all your dozen of nurslings cry— What did the other children do? And what were childhood, wanting you? |

|

The red room with the giant bed Where none but elders lay their head; The little room where you and I Did for a while together lie, And, simple suitor, I your hand In decent marriage did demand; The great day-nursery, best of all, With pictures pasted on the wall And leaves upon the blind— A pleasant room wherein to wake And hear the leafy garden shake And rustle in the wind— And pleasant there to lie in bed And see the pictures overhead— The wars about Sebastopol, The grinning guns along the wall, The daring escalade, The plunging ships, the bleating sheep, The happy children ankle-deep, And laughing as they wade: All these are vanished clean away, And the old manse is changed to-day; It wears an altered face And shields a stranger race. The river, on from mill to mill, Flows past our childhood’s garden still; But ah! we children never more Shall watch it from the water-door! Below the yew—it still is there— Our phantom voices haunt the air As we were still at play, And I can hear them call and say: “How far is it to Babylon?” Ah, far enough, my dear, Far, far enough from here— Yet you have farther gone! “Can I get there by candlelight?” So goes the old refrain. I do not know—perchance you might— But only, children, hear it right, Ah, never to return again! The eternal dawn, beyond a doubt, Shall break on hill and plain, And put all stars and candles out, Ere we be young again. To you in distant India, these I send across the seas, Nor count it far across. For which of us forgets The Indian cabinets, The bones of antelope, the wings of albatross, The pied and painted birds and beans, The junks and bangles, beads and screens, The gods and sacred bells, And the loud-humming, twisted shells? The level of the parlour floor Was honest, homely, Scottish shore; But when we climbed upon a chair, Behold the gorgeous East was there! Be this a fable; and behold Me in the parlour as of old, And Minnie just above me set In the quaint Indian cabinet! Smiling and kind, you grace a shelf Too high for me to reach myself. Reach down a hand, my dear, and take These rhymes for old acquaintance’ sake. |

|

Some day soon this rhyming volume, if you learn with proper speed, Little Louis Sanchez, will be given you to read. Then shall you discover that your name was printed down By the English printers, long before, in London town. In the great and busy city where the East and West are met, All the little letters did the English printer set; While you thought of nothing, and were still too young to play, Foreign people thought of you in places far away. Ay, and while you slept, a baby, over all the English lands Other little children took the volume in their hands; Other children questioned, in their homes across the seas: Who was little Louis, won’t you tell us, mother, please? 2Now that you have spelt your lesson, lay it down and go and play, Seeking shells and seaweed on the sands of Monterey, Watching all the mighty whalebones, lying buried by the breeze, Tiny sandy-pipers, and the huge Pacific seas. And remember in your playing, as the sea-fog rolls to you, Long ere you could read it, how I told you what to do; And that while you thought of no one, nearly half the world away Some one thought of Louis on the beach of Monterey! |

|

As from the house your mother sees You playing round the garden trees, So you may see, if you will look Through the windows of this book, Another child, far, far away, And in another garden, play. But do not think you can at all, By knocking on the window, call That child to hear you. He intent Is all on his play-business bent. He does not hear; he will not look, Not yet be lured out of this book. For, long ago, the truth to say, He has grown up and gone away, And it is but a child of air That lingers in the garden there. |

|

Of all my verse, like not a single line; But like my title, for it is not mine. That title from a better man I stole; Ah, how much better, had I stol’n the whole! |

There are men and classes of men that stand above the common herd: the soldier, the sailor, and the shepherd not unfrequently; the artist rarely; rarelier still, the clergyman; the physician almost as a rule. He is the flower (such as it is) of our civilisation; and when that stage of man is done with, and only remembered to be marvelled at in history, he will be thought to have shared as little as any in the defects of the period, and most notably exhibited the virtues of the race. Generosity he has, such as is possible to those who practise an art, never to those who drive a trade; discretion, tested by a hundred secrets; tact, tried in a thousand embarrassments; and, what are more important, Heraclean cheerfulness and courage. So it is that he brings air and cheer into the sickroom, and often enough, though not so often as he wishes, brings healing.

Gratitude is but a lame sentiment; thanks, when they are expressed, are often more embarrassing than welcome; and yet I must set forth mine to a few out of many doctors who have brought me comfort and help: to Dr. Willey of San Francisco, whose kindness to a stranger it must be as grateful to him, as it is touching to me, to remember; to Dr. Karl Ruedi of Davos, the good genius of the English in his frosty mountains; to Dr. Herbert of Paris, whom I knew only for a week, and to Dr. Caissot of Montpellier, whom I knew only for ten days, and who have yet written their names deeply in my memory; to Dr. Brandt of Royat; to Dr. Wakefield of Nice; to Dr. Chepmell, whose visits make it a pleasure to be ill; to Dr. Horace Dobell, so wise in counsel; to Sir Andrew Clark, so unwearied in kindness; and to that wise youth, my uncle, Dr. Balfour.

I forget as many as I remember; and I ask both to pardon me, these for silence, those for inadequate speech. But one name I have kept on purpose to the last, because it is a household word with me, and because if I had not received favours from so many hands and in so many quarters of the world, it should have stood upon this page alone: that of my friend Thomas Bodley Scott of Bournemouth. Will he accept this, although shared among so many, for a dedication to himself? and when next my ill-fortune (which has thus its pleasant side) brings him hurrying to me when he would fain sit down to meat or lie down to rest, will he care to remember that he takes this trouble for one who is not fool enough to be ungrateful?

R. L. S.

Skerryvore,

Bournemouth.

|

Go, little book, and wish to all Flowers in the garden, meat in the hall, A bin of wine, a spice of wit, A house with lawns enclosing it, A living river by the door, A nightingale in the sycamore! |

|

The gauger walked with willing foot, And aye the gauger played the flute; And what should Master Gauger play But Over the hills and far away? Whene’er I buckle on my pack And foot it gaily in the track, O pleasant gauger, long since dead, I hear you fluting on ahead. You go with me the selfsame way— The selfsame air for me you play; For I do think and so do you It is the tune to travel to. For who would gravely set his face To go to this or t’other place? There’s nothing under heav’n so blue That’s fairly worth the travelling to. On every hand the roads begin, And people walk with zeal therein; But wheresoe’er the highways tend, Be sure there’s nothing at the end. Then follow you, wherever hie The travelling mountains of the sky. Or let the streams in civil mode Direct your choice upon a road; For one and all, or high or low, Will lead you where you wish to go; And one and all go night and day Over the hills and far away! Forest of Montargis, 1878. |

|

On the great streams the ships may go About men’s business to and fro. But I, the egg-shell pinnace, sleep On crystal waters ankle-deep: I, whose diminutive design, Of sweeter cedar, pithier pine, Is fashioned on so frail a mould, A hand may launch, a hand withhold: I, rather, with the leaping trout Wind, among lilies, in and out; I, the unnamed, inviolate, Green, rustic rivers navigate; My dipping paddle scarcely shakes The berry in the bramble-brakes; Still forth on my green way I wend Beside the cottage garden-end; And by the nested angler fare, And take the lovers unaware. By willow wood and water-wheel Speedily fleets my touching keel; By all retired and shady spots Where prosper dim forget-me-nots; By meadows where at afternoon The growing maidens troop in June To loose their girdles on the grass. Ah! speedier than before the glass The backward toilet goes; and swift As swallows quiver, robe and shift And the rough country stockings lie Around each young divinity. When, following the recondite brook, Sudden upon this scene I look, And light with unfamiliar face On chaste Diana’s bathing-place, Loud ring the hills about and all The shallows are abandoned.... |

|

It is the season now to go About the country high and low, Among the lilacs hand in hand, And two by two in fairyland. The brooding boy, the sighing maid, Wholly fain and half afraid, Now meet along the hazel’d brook To pass and linger, pause and look. A year ago, and blithely paired, Their rough-and-tumble play they shared; They kissed and quarrelled, laughed and cried, A year ago at Eastertide. With bursting heart, with fiery face, She strove against him in the race; He unabashed her garter saw, That now would touch her skirts with awe. Now by the stile ablaze she stops, And his demurer eyes he drops; Now they exchange averted sighs Or stand and marry silent eyes. And he to her a hero is And sweeter she than primroses; Their common silence dearer far Than nightingale and mavis are. Now when they sever wedded hands, Joy trembles in their bosom-strands And lovely laughter leaps and falls Upon their lips in madrigals. |

|

A naked house, a naked moor, A shivering pool before the door, A garden bare of flowers and fruit And poplars at the garden foot: Such is the place that I live in, Bleak without and bare within. Yet shall your ragged moor receive The incomparable pomp of eve, And the cold glories of the dawn Behind your shivering trees be drawn; And when the wind from place to place Doth the unmoored cloud-galleons chase, Your garden gloom and gleam again, With leaping sun, with glancing rain. Here shall the wizard moon ascend The heavens, in the crimson end Of day’s declining splendour; here The army of the stars appear. The neighbour hollows, dry or wet, Spring shall with tender flowers beset; And oft the morning muser see Larks rising from the broomy lea, And every fairy wheel and thread Of cobweb, dew-bediamonded. When daisies go, shall winter-time Silver the simple grass with rime; Autumnal frosts enchant the pool And make the cart-ruts beautiful; And when snow-bright the moor expands, How shall your children clap their hands! To make this earth, our hermitage, A cheerful and a changeful page, God’s bright and intricate device Of days and seasons doth suffice. |

|

Far from the loud sea beaches Where he goes fishing and crying, Here in the inland garden Why is the sea-gull flying? Here are no fish to dive for; Here is the corn and lea; Here are the green trees rustling. Hie away home to sea! Fresh is the river water And quiet among the rushes; This is no home for the sea-gull, But for the rooks and thrushes. Pity the bird that has wandered! Pity the sailor ashore! Hurry him home to the ocean, Let him come here no more! High on the sea-cliff ledges The white gulls are trooping and crying, Here among rooks and roses, Why is the sea-gull flying? |

|

Friend, in my mountain-side demesne, My plain-beholding, rosy, green And linnet-haunted garden-ground, Let still the esculents abound. Let first the onion flourish there, Rose among roots, the maiden-fair, Wine-scented and poetic soul Of the capacious salad-bowl. Let thyme the mountaineer (to dress The tinier birds) and wading cress, The lover of the shallow brook, From all my plots and borders look. Nor crisp and ruddy radish, nor Pease-cods for the child’s pinafore Be lacking; nor of salad clan The last and least that ever ran About great nature’s garden-beds. Nor thence be missed the speary heads Of artichoke; nor thence the bean That gathered innocent and green Outsavours the belauded pea. These tend, I prithee; and for me, Thy most long-suffering master, bring In April, when the linnets sing And the days lengthen more and more, At sundown to the garden door. And I, being provided thus, Shall, with superb asparagus, A book, a taper, and a cup Of country wine, divinely sup. La Solitude, Hyères. |

|

A picture-frame for you to fill, A paltry setting for your face, A thing that has no worth until You lend it something of your grace, I send (unhappy I that sing Laid by a while upon the shelf) Because I would not send a thing Less charming than you are yourself. And happier than I, alas! (Dumb thing, I envy its delight) ’Twill wish you well, the looking-glass, And look you in the face to-night. 1869. |

|

A lover of the moorland bare And honest country winds you were; The silver-skimming rain you took; And love the floodings of the brook, Dew, frost and mountains, fire and seas, Tumultuary silences, Winds that in darkness fifed a tune, And the high-riding, virgin moon. And as the berry, pale and sharp, Springs on some ditch’s counterscarp In our ungenial, native north— You put your frosted wildings forth, And on the heath, afar from man, A strong and bitter virgin ran. The berry ripened keeps the rude And racy flavour of the wood. And you that loved the empty plain All redolent of wind and rain, Around you still the curlew sings— The freshness of the weather clings— The maiden jewels of the rain Sit in your dabbled locks again. |

|

The unfathomable sea, and time, and tears, The deeds of heroes and the crimes of kings Dispart us; and the river of events Has, for an age of years, to east and west More widely borne our cradles. Thou to me Art foreign, as when seamen at the dawn Descry a land far off, and know not which. So I approach uncertain; so I cruise Round thy mysterious islet, and behold Surf and great mountains and loud river-bars, And from the shore hear inland voices call. Strange is the seaman’s heart; he hopes, he fears; Draws closer and sweeps wider from that coast; Last, his rent sail refits, and to the deep His shattered prow uncomforted puts back. Yet as he goes he ponders at the helm Of that bright island; where he feared to touch, His spirit re-adventures; and for years, Where by his wife he slumbers safe at home, Thoughts of that land revisit him; he sees The eternal mountains beckon, and awakes Yearning for that far home that might have been. |

|

Youth now flees on feathered foot, Faint and fainter sounds the flute, Rarer songs of gods; and still Somewhere on the sunny hill, Or along the winding stream, Through the willows, flits a dream; Flits but shows a smiling face, Flees, but with so quaint a grace, None can choose to stay at home, All must follow, all must roam. This is unborn beauty: she Now in air floats high and free. Takes the sun and makes the blue;— Late with stooping pinion flew Raking hedgerow trees, and wet Her wing in silver streams, and set Shining foot on temple roof: Now again she flies aloof, Coasting mountain clouds and kiss’t By the evening’s amethyst. In wet wood and miry lane, Still we pant and pound in vain; Still with leaden foot we chase Waning pinion, fainting face; Still with grey hair we stumble on, Till, behold, the vision gone! Where hath fleeting beauty led? To the doorway of the dead. Life is over, life was gay: We have come the primrose way. |

|

Even in the bluest noonday of July, There could not run the smallest breath of wind But all the quarter sounded like a wood; And in the chequered silence and above The hum of city cabs that sought the Bois, Suburban ashes shivered into song. A patter and a chatter and a chirp And a long dying hiss—it was as though Starched old brocaded dames through all the house Had trailed a strident skirt, or the whole sky Even in a wink had over-brimmed in rain. Hark, in these shady parlours, how it talks Of the near Autumn, how the smitten ash Trembles and augurs floods! O not too long In these inconstant latitudes delay, O not too late from the unbeloved north Trim your escape! For soon shall this low roof Resound indeed with rain, soon shall your eyes Search the foul garden, search the darkened rooms, Nor find one jewel but the blazing log. 12 Rue Vernier, Paris. |

|

I sit and wait a pair of oars On cis-Elysian river-shores. Where the immortal dead have sate, ’Tis mine to sit and meditate; To re-ascend life’s rivulet, Without remorse, without regret; And sing my Alma Genetrix Among the willows of the Styx. And lo, as my serener soul Did these unhappy shores patrol, And wait with an attentive ear The coming of the gondolier, Your fire-surviving roll I took, Your spirited and happy book;1 Whereon, despite my frowning fate, It did my soul so recreate That all my fancies fled away On a Venetian holiday. Now, thanks to your triumphant care, Your pages clear as April air, The sails, the bells, the birds, I know, And the far-off Friulan snow; The land and sea, the sun and shade, And the blue even lamp-inlaid. For this, for these, for all, O friend, For your whole book from end to end— For Paron Piero’s mutton-ham— I your defaulting debtor am. Perchance, reviving, yet may I To your sea-paven city hie, And in a felze some day yet Light at your pipe my cigarette. |

1 “Life on the Lagoons,” by H. F. Brown, originally burned in the fire at Messrs. Kegan Paul, Trench & Co.’s.

|

Dear Andrew, with the brindled hair, Who glory to have thrown in air, High over arm, the trembling reed, By Ale and Kail, by Till and Tweed: An equal craft of hand you show The pen to guide, the fly to throw: I count you happy-starred; for God, When He with inkpot and with rod Endowed you, bade your fortune lead For ever by the crooks of Tweed, For ever by the woods of song And lands that to the Muse belong; Or if in peopled streets, or in The abhorred pedantic sanhedrin, It should be yours to wander, still Airs of the morn, airs of the hill, The plovery Forest and the seas That break about the Hebrides, Should follow over field and plain And find you at the window-pane; And you again see hill and peel, And the bright springs gush at your heel. So went the fiat forth, and so Garrulous like a brook you go, With sound of happy mirth and sheen Of daylight—whether by the green You fare that moment, or the grey; Whether you dwell in March or May; Or whether treat of reels and rods Or of the old unhappy gods: Still like a brook your page has shone, And your ink sings of Helicon. |

|

In ancient tales, O friend, thy spirit dwelt; There, from of old, thy childhood passed; and there High expectation, high delights and deeds, Thy fluttering heart with hope and terror moved. And thou hast heard of yore the Blatant Beast, And Roland’s horn, and that war-scattering shout Of all-unarmed Achilles, ægis-crowned. And perilous lands thou sawest, sounding shores And seas and forests drear, island and dale And mountain dark. For thou with Tristram rod’st Or Bedevere, in farthest Lyonesse. Thou hadst a booth in Samarcand, whereat Side-looking Magians trafficked; thence, by night, An Afreet snatched thee, and with wings upbore Beyond the Aral Mount; or, hoping gain, Thou, with a jar of money, didst embark For Balsorah by sea. But chiefly thou In that clear air took’st life; in Arcady The haunted, land of song; and by the wells Where most the gods frequent. There Chiron old, In the Pelethronian antre, taught thee lore; The plants he taught, and by the shining stars In forests dim to steer. There hast thou seen Immortal Pan dance secret in a glade, And, dancing, roll his eyes; these, where they fell, Shed glee, and through the congregated oaks A flying horror winged; while all the earth To the god’s pregnant footing thrilled within. Or whiles, beside the sobbing stream, he breathed, In his clutched pipe unformed and wizard strains Divine yet brutal; which the forest heard, And thou, with awe; and far upon the plain The unthinking ploughman started and gave ear. Now things there are that, upon him who sees, A strong vocation lay; and strains there are That whoso hears shall hear for evermore. For evermore thou hear’st immortal Pan And those melodious godheads, ever young And ever quiring, on the mountains old. What was this earth, child of the gods, to thee? Forth from thy dreamland thou, a dreamer, cam’st And in thine ears the olden music rang, And in thy mind the doings of the dead, And those heroic ages long forgot. To a so fallen earth, alas! too late, Alas! in evil days, thy steps return, To list at noon for nightingales, to grow A dweller on the beach till Argo come That came long since, a lingerer by the pool Where that desirèd angel bathes no more. As when the Indian to Dakota comes, Or farthest Idaho, and where he dwelt, He with his clan, a humming city finds; Thereon a while, amazed, he stares, and then To right and leftward, like a questing dog, Seeks first the ancestral altars, then the hearth Long cold with rains, and where old terror lodged, And where the dead: so thee undying Hope, With all her pack, hunts screaming through the years: Here, there, thou fleeëst; but nor here nor there The pleasant gods abide, the glory dwells. That, that was not Apollo, not the god. This was not Venus, though she Venus seemed A moment. And though fair yon river move, She, all the way, from disenchanted fount To seas unhallowed runs; the gods forsook Long since her trembling rushes; from her plains Disconsolate, long since adventure fled; And now although the inviting river flows, And every poplared cape, and every bend Or willowy islet, win upon thy soul And to thy hopeful shallop whisper speed; Yet hope not thou at all; hope is no more; And O, long since the golden groves are dead The faëry cities vanished from the land! |

|

The year runs through her phases; rain and sun, Spring-time and summer pass; winter succeeds; But one pale season rules the house of death. Cold falls the imprisoned daylight; fell disease By each lean pallet squats, and pain and sleep Toss gaping on the pillows. But O thou! Uprise and take thy pipe. Bid music flow, Strains by good thoughts attended, like the spring The swallows follow over land and sea. Pain sleeps at once; at once, with open eyes, Dozing despair awakes. The shepherd sees His flock come bleating home; the seaman hears Once more the cordage rattle. Airs of home! Youth, love, and roses blossom; the gaunt ward Dislimns and disappears, and, opening out, Shows brooks and forests, and the blue beyond Of mountains. Small the pipe; but O! do thou, Peak-faced and suffering piper, blow therein The dirge of heroes dead; and to these sick, These dying, sound the triumph over death. Behold! each greatly breathes; each tastes a joy Unknown before, in dying; for each knows A hero dies with him—though unfulfilled, Yet conquering truly—and not dies in vain. So is pain cheered, death comforted; the house Of sorrow smiles to listen. Once again— O thou, Orpheus and Heracles, the bard And the deliverer, touch the stops again! |

|

Who comes to-night? We ope the doors in vain. Who comes? My bursting walls, can you contain The presences that now together throng Your narrow entry, as with flowers and song, As with the air of life, the breath of talk? Lo, how these fair immaculate women walk Behind their jocund maker; and we see Slighted De Mauves, and that far different she, Gressie, the trivial sphynx; and to our feast Daisy and Barb and Chancellor (she not least!) With all their silken, all their airy kin, Do like unbidden angels enter in. But he, attended by these shining names, Comes (best of all) himself—our welcome James. |

|

Where the bells peal far at sea Cunning fingers fashioned me. There on palace walls I hung While that Consuelo sung; But I heard, though I listened well, Never a note, never a trill, Never a beat of the chiming bell. There I hung and looked, and there In my grey face, faces fair Shone from under shining hair. Well I saw the poising head, But the lips moved and nothing said; And when lights were in the hall, Silent moved the dancers all. So a while I glowed, and then Fell on dusty days and men; Long I slumbered packed in straw, Long I none but dealers saw; Till before my silent eye One that sees came passing by. Now with an outlandish grace, To the sparkling fire I face In the blue room at Skerryvore; Where I wait until the door Open, and the Prince of Men, Henry James, shall come again. |

|

We see you as we see a face That trembles in a forest place Upon the mirror of a pool For ever quiet, clear, and cool; And, in the wayward glass, appears To hover between smiles and tears, Elfin and human, airy and true, And backed by the reflected blue. |

|

I read, dear friend, in your dear face Your life’s tale told with perfect grace; The river of your life I trace Up the sun-chequered, devious bed To the far-distant fountain-head. Not one quick beat of your warm heart, Nor thought that came to you apart, Pleasure nor pity, love nor pain Nor sorrow, has gone by in vain; But as some lone, wood-wandering child Brings home with him at evening mild The thorns and flowers of all the wild, From your whole life, O fair and true, Your flowers and thorns you bring with you! |

|

Under the wide and starry sky, Dig the grave and let me lie. Glad did I live and gladly die, And I laid me down with a will. This be the verse you grave for me: Here he lies where he longed to be; Home is the sailor, home from sea, And the hunter home from the hill. Hyères, May 1884. |

|