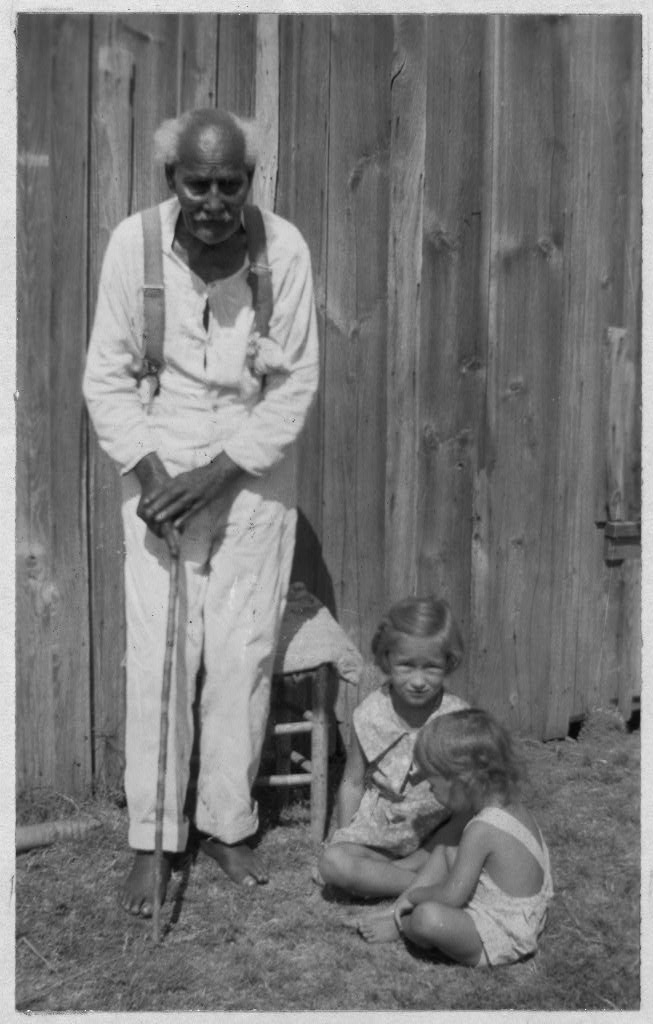

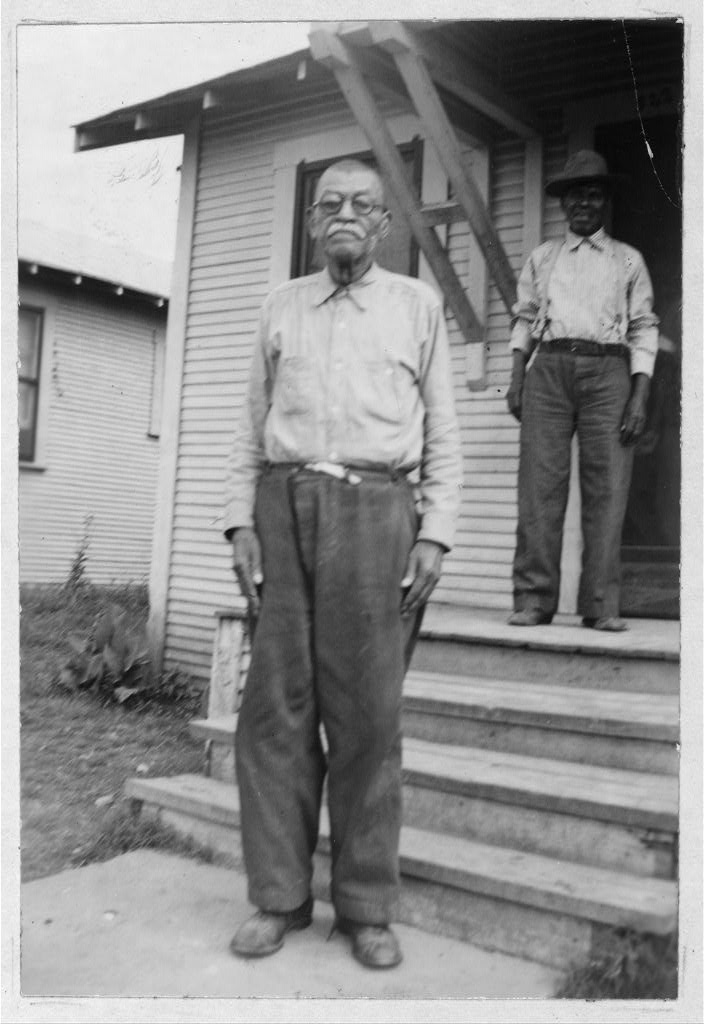

Will Adams

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Slave Narratives: a Folk History of Slavery

in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves, by Work Projects Administration

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Slave Narratives: a Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves

Texas Narratives, Part 1

Author: Work Projects Administration

Release Date: December 2, 2009 [EBook #30576]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SLAVE NARRATIVES--TEXAS, PART 1 ***

Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by the Library of Congress,

Manuscript Division)

Transcriber's Note: |

| I. Inconsistent punctuation has been silently corrected throughout the book. |

| II. Clear spelling mistakes have been corrected however, inconsistent languague usage (such as 'day' and 'dey') has been maintained. A list of corrections is included at the end of the book. |

| III. The numbers at the start of each chapter were stamped into the original scan and refer to the number of the published interview in the context of the entire Slave Narratives project. |

| IV. Two handwritten notes have been retained and are annotated as such. |

A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves

TYPEWRITTEN RECORDS PREPARED BY

THE FEDERAL WRITERS' PROJECT

1936-1938

ASSEMBLED BY

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS PROJECT

WORK PROJECTS ADMINISTRATION

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

SPONSORED BY THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Illustrated with Photographs

WASHINGTON 1941

VOLUME XVI

Prepared by the Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration for the State of Texas

INFORMANTS | |

| Adams, Will | 1 |

| Adams, William | 4 |

| Adams, William M. | 9 |

| Allen, Sarah | 12 |

| Anderson, Andy | 14 |

| Anderson, George Washington (Wash) | 17 |

| Anderson, Willis | 21 |

| Armstrong, Mary | 25 |

| Arnwine, Stearlin | 31 |

| Ashley, Sarah | 34 |

| Babino, Agatha | 37 |

| Barclay, Mrs. John | 39 |

| Barker, John | 42 |

| Barnes, Joe | 45 |

| Barrett, Armstead | 47 |

| Barrett, Harriet | 49 |

| Bates, John | 51 |

| Beckett, Harrison | 54 |

| Bell, Frank | 59 |

| Bell, Virginia | 62 |

| Bendy, Edgar | 66 |

| Bendy, Minerva | 68 |

| Benjamin, Sarah | 70 |

| Bess, Jack | 72 |

| Betts, Ellen | 75 |

| Beverly, Charlotte | 84 |

| Black, Francis | 87 |

| Blanchard, Olivier | 90 |

| Blanks, Julia | 93 |

| Boles, Elvira | 106 |

| Bormer (Bonner), Betty | 109 |

| Boyd, Harrison | 112 |

| Boyd, Issabella | 114 |

| Boyd, James | 117 |

| Boykins, Jerry | 121 |

| Brackins, Monroe | 124 |

| Bradshaw, Gus | 130 |

| Brady, Wes | 133 |

| Branch, Jacob | 137 |

| Branch, William | 143 |

| Brim, Clara | 147 |

| Brooks, Sylvester | 149 |

| Broussard, Donaville | 151 |

| Brown, Fannie | 154 |

| Brown, Fred | 156 |

| Brown, James | 160 |

| Brown, Josie | 163 |

| Brown, Zek | 166 |

| Bruin, Madison | 169 |

| Bunton, Martha Spence | 174 |

| Butler, Ellen | 176 |

| Buttler, Henry H. | 179 |

| Byrd, William | 182 |

| Cain, Louis | 185 |

| Calhoun, Jeff | 188 |

| Campbell, Simp | 191 |

| Cape, James | 193 |

| Carruthers, Richard | 197 |

| Carter, Cato | 202 |

| Cauthern, Jack | 212 |

| Chambers, Sally Banks | 214 |

| Choice, Jeptha | 217 |

| Clark, Amos | 220 |

| Clark, Anne | 223 |

| Cole, Thomas | 225 |

| Coleman, Eli | 236 |

| Coleman, Preely | 240 |

| Collins, Harriet | 242 |

| Columbus, Andrew (Smoky) | 246 |

| Connally, Steve | 249 |

| Cormier, Valmar | 252 |

| Cornish, Laura | 254 |

| Crawford, John | 257 |

| Cumby, Green | 260 |

| Cummins, Tempie | 263 |

| Cunningham, Adeline | 266 |

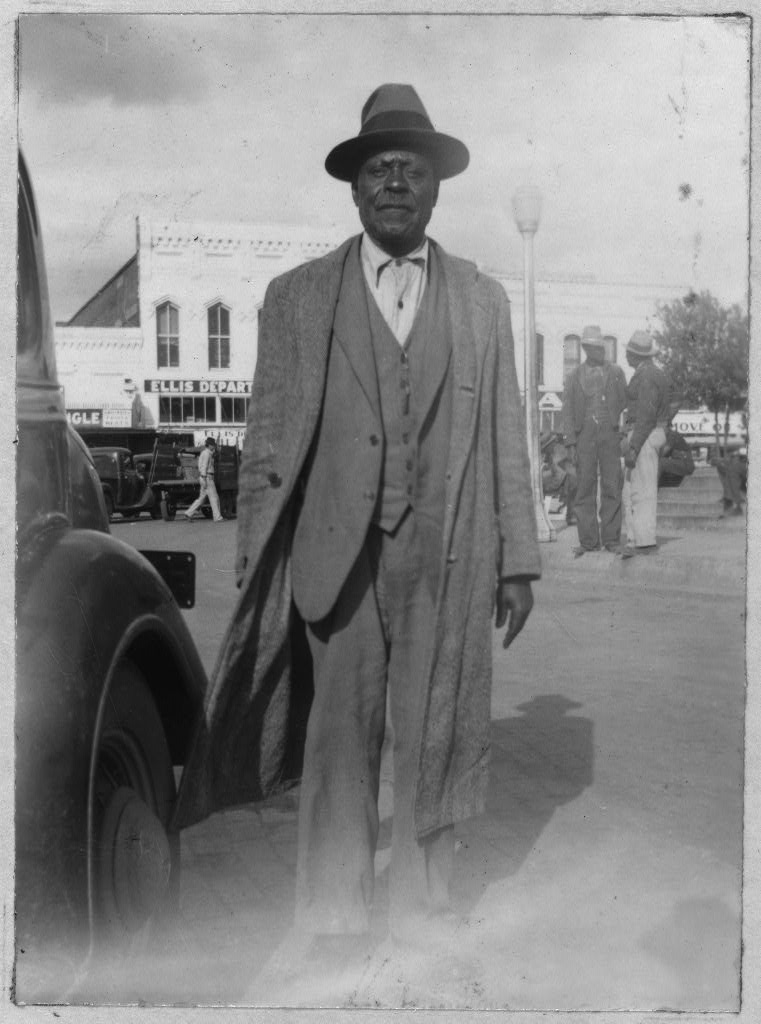

| Daily, Will | 269 |

| Daniels, Julia Francis | 273 |

| Darling, Katie | 278 |

| Davenport, Carey | 281 |

| Davis, Campbell | 285 |

| Davis, William | 289 |

| Davison, Eli | 295 |

| Davison, Elige | 298 |

| Day, John | 302 |

| Denson, Nelsen | 305 |

| Duhon, Victor | 307 |

ILLUSTRATIONS | |

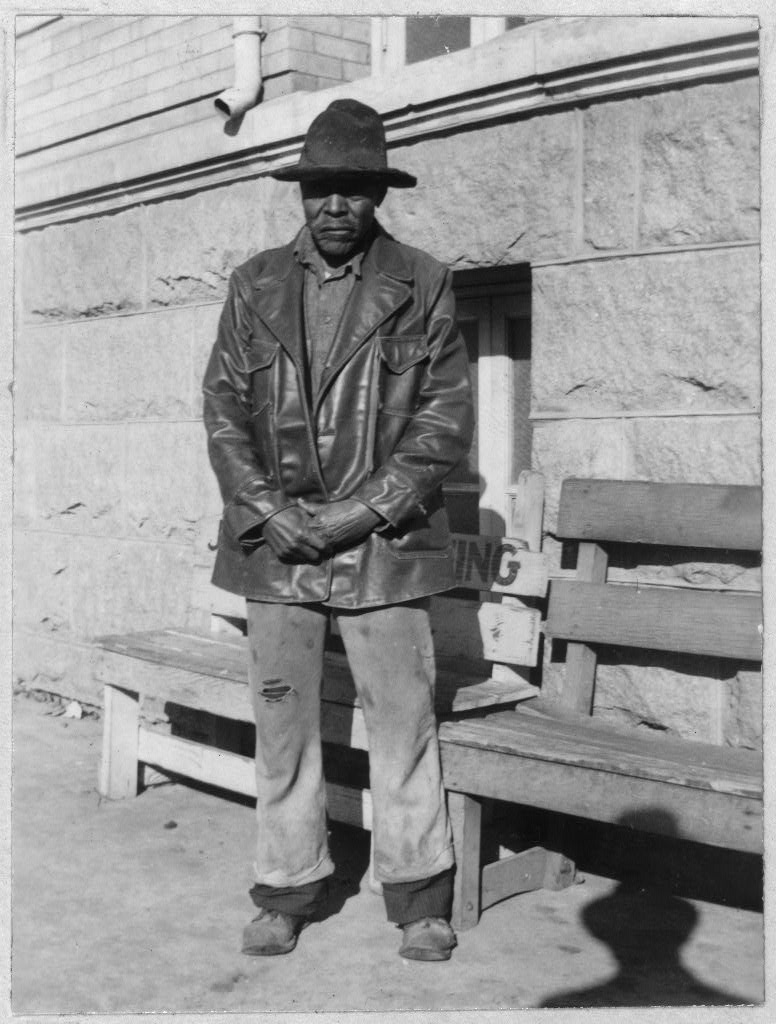

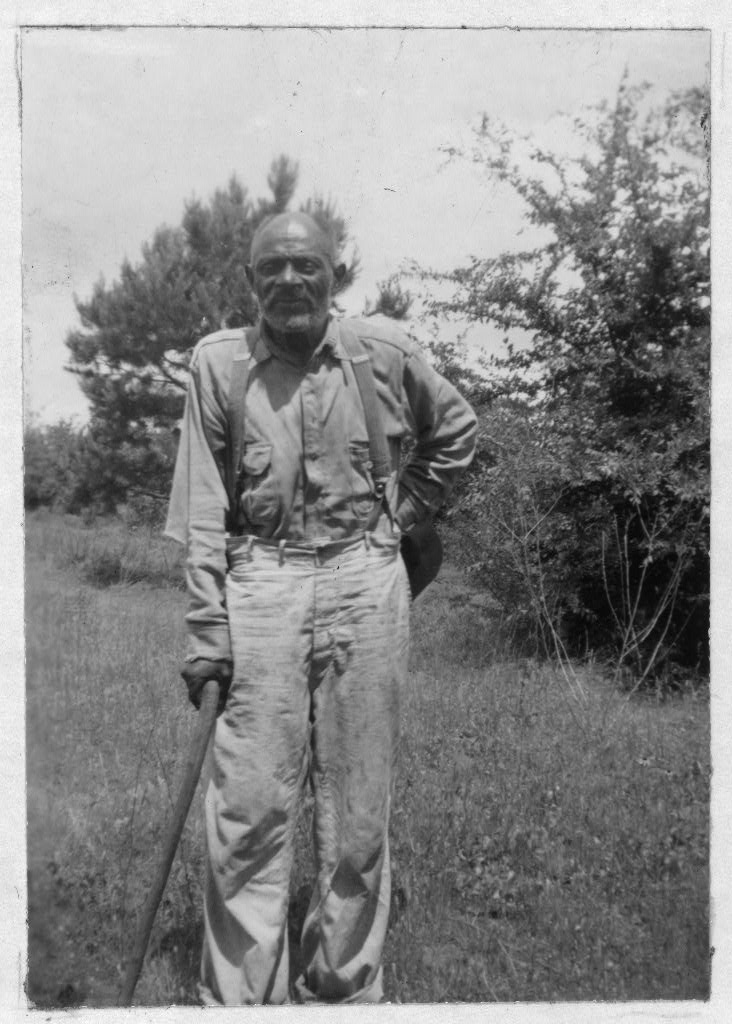

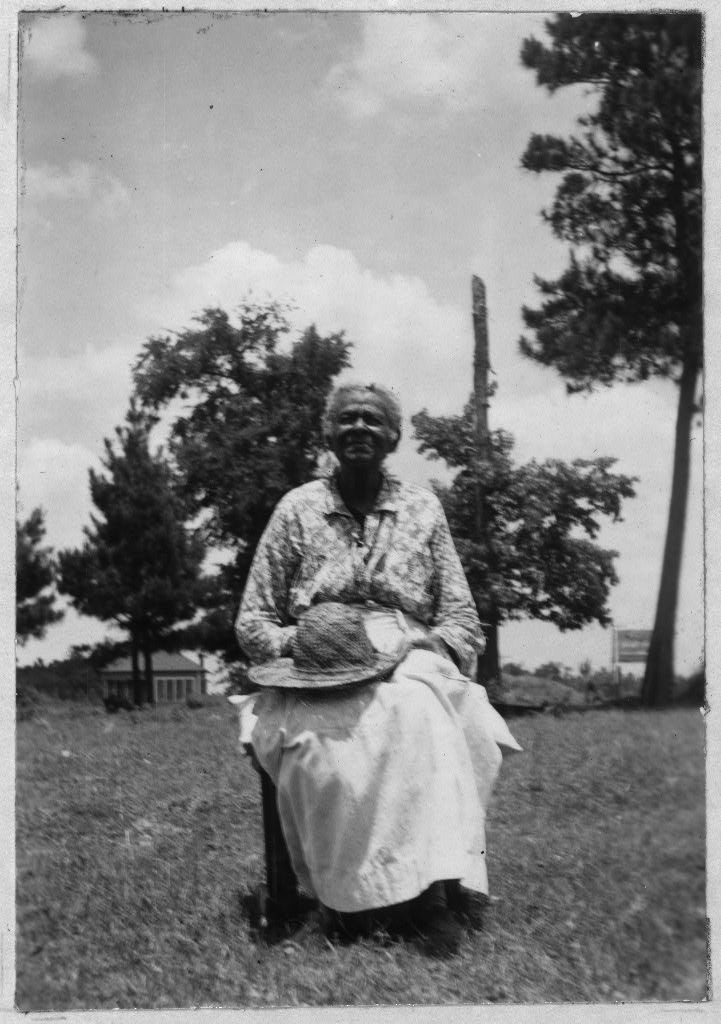

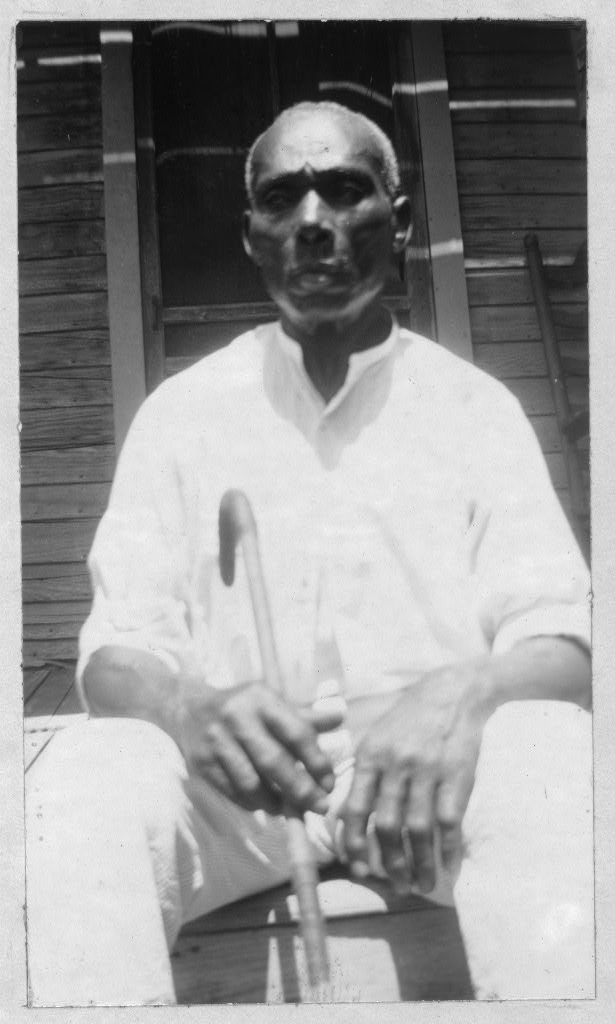

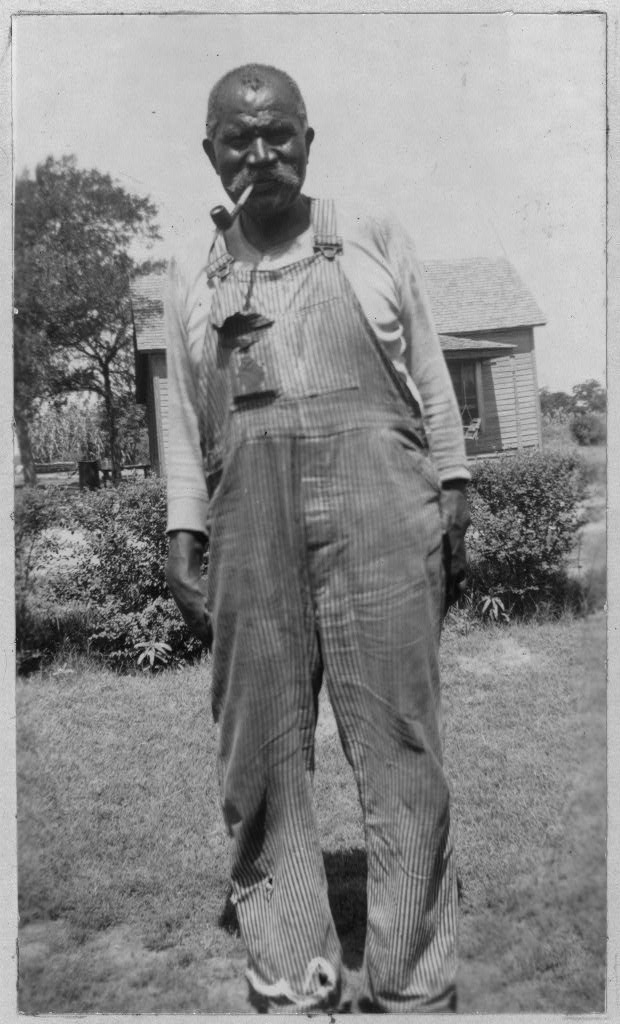

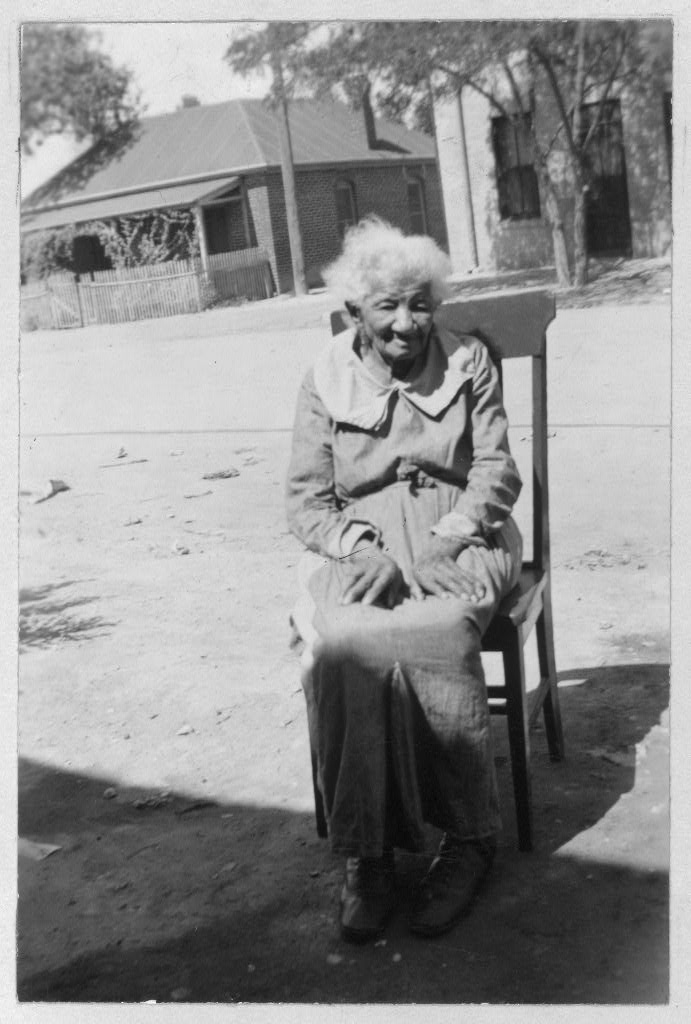

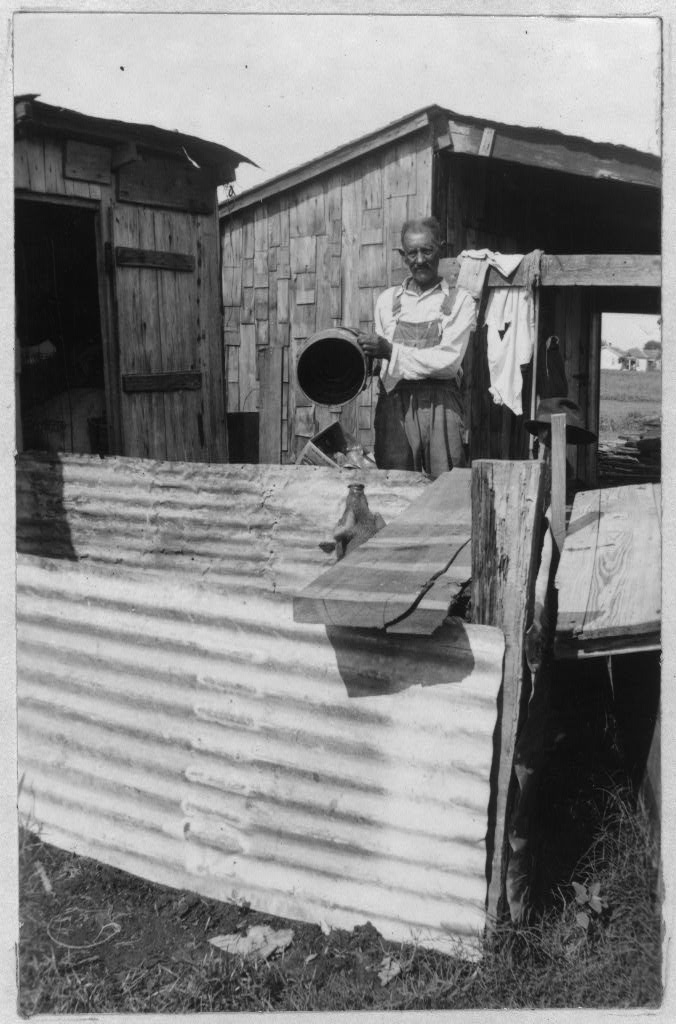

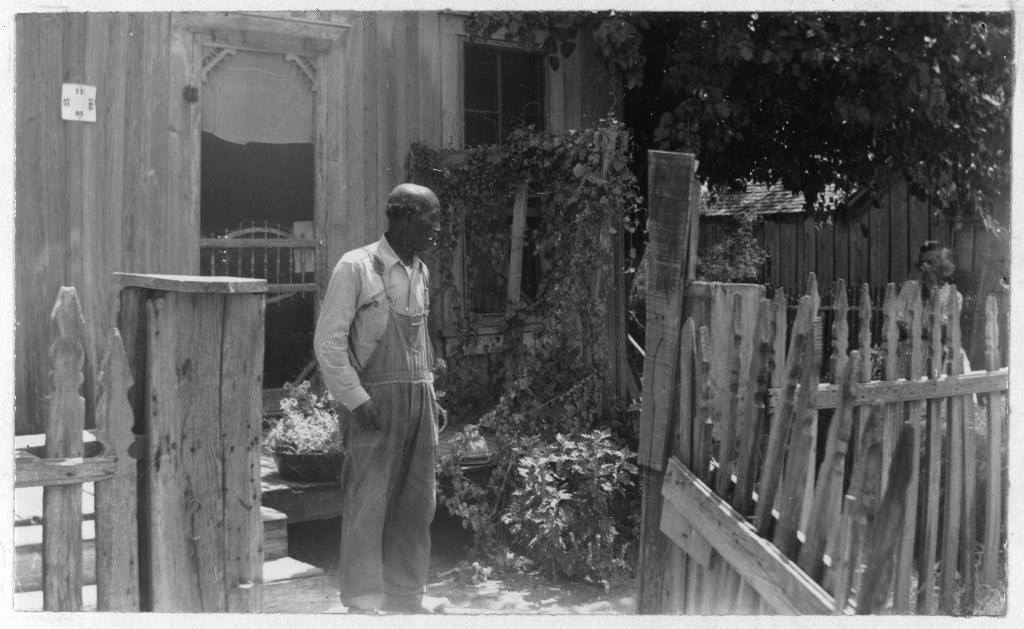

| Will Adams | 1 |

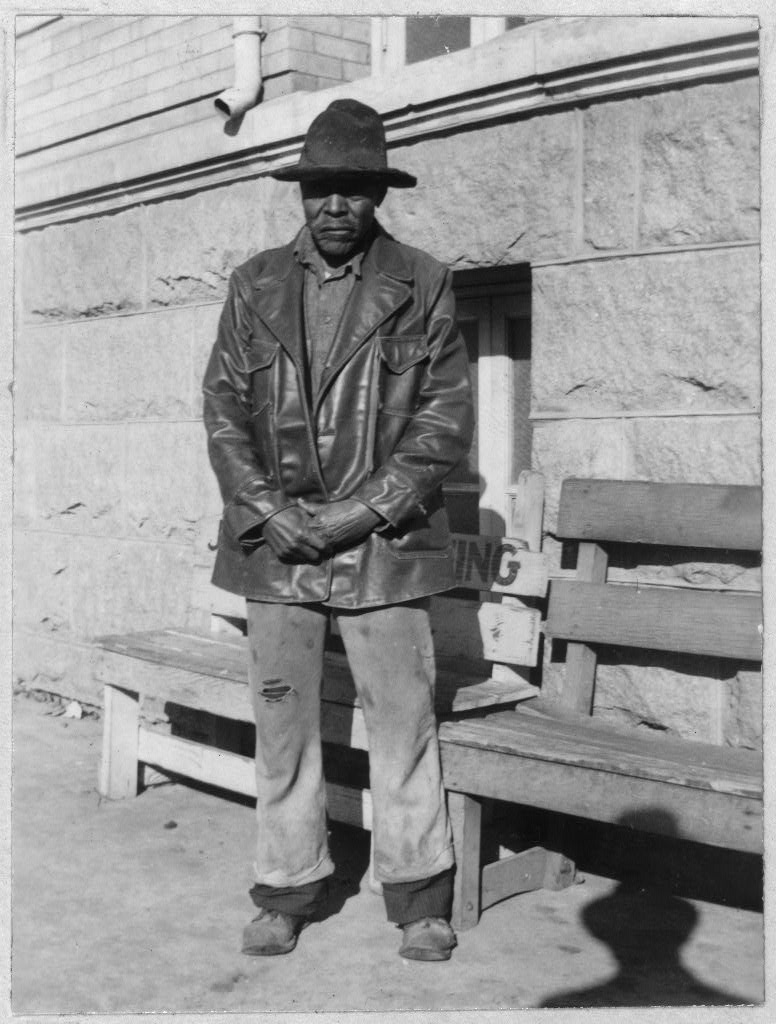

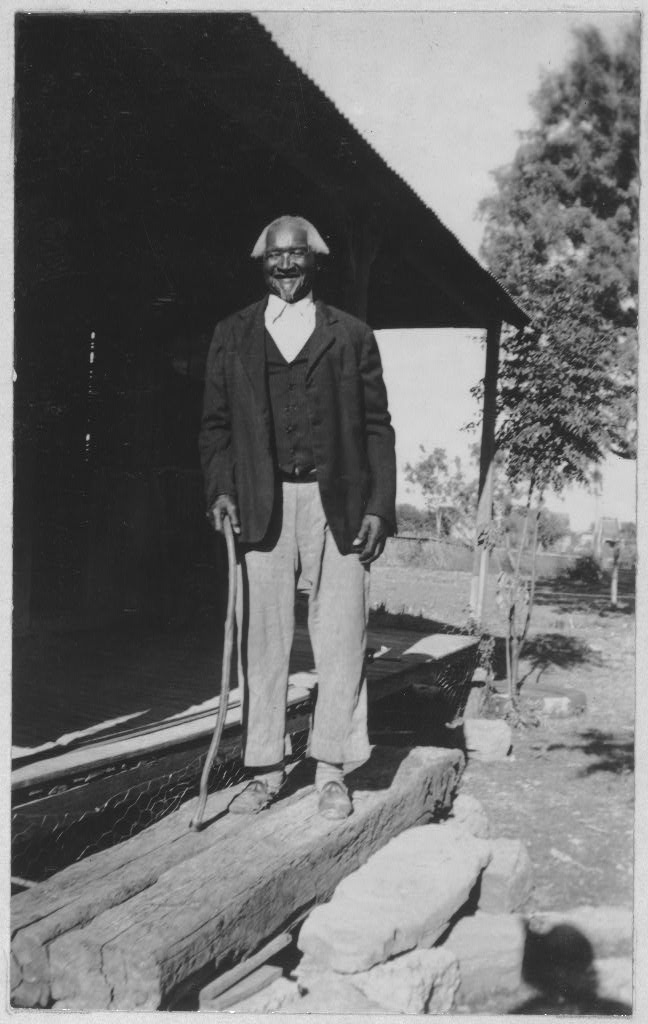

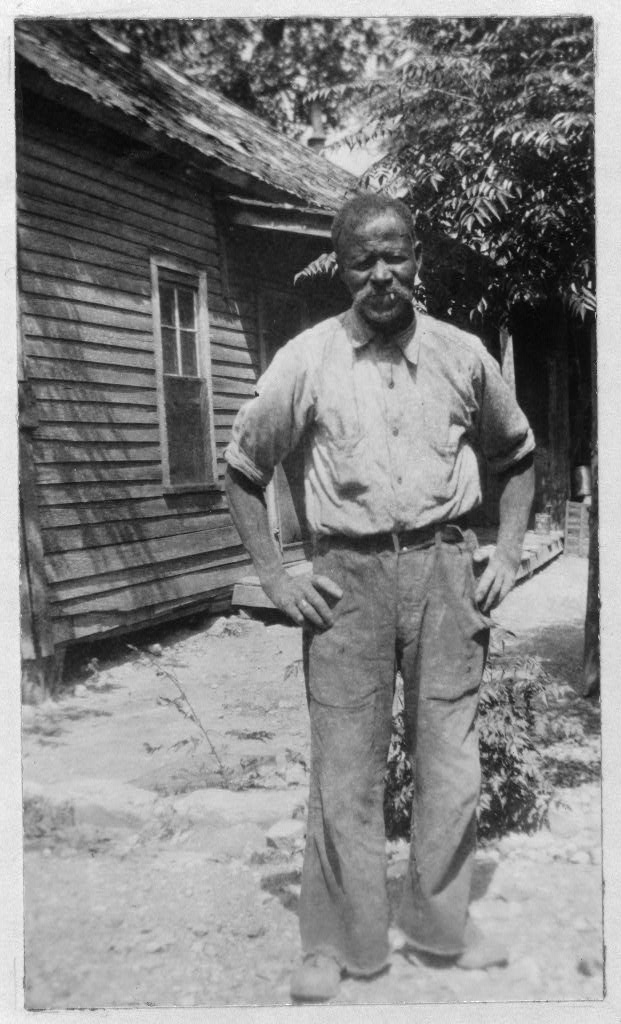

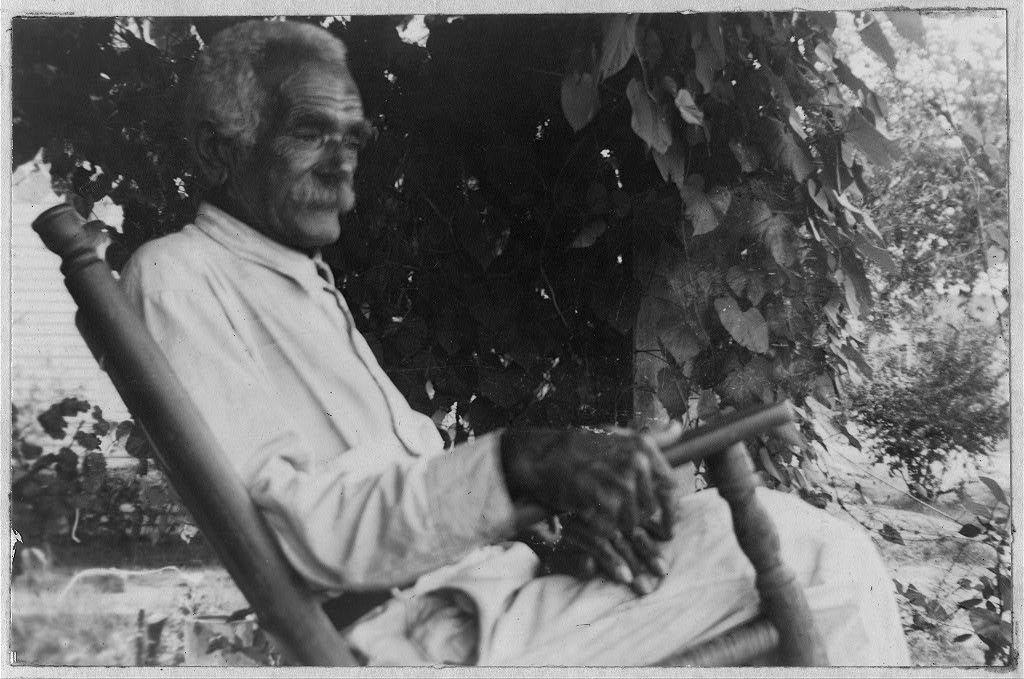

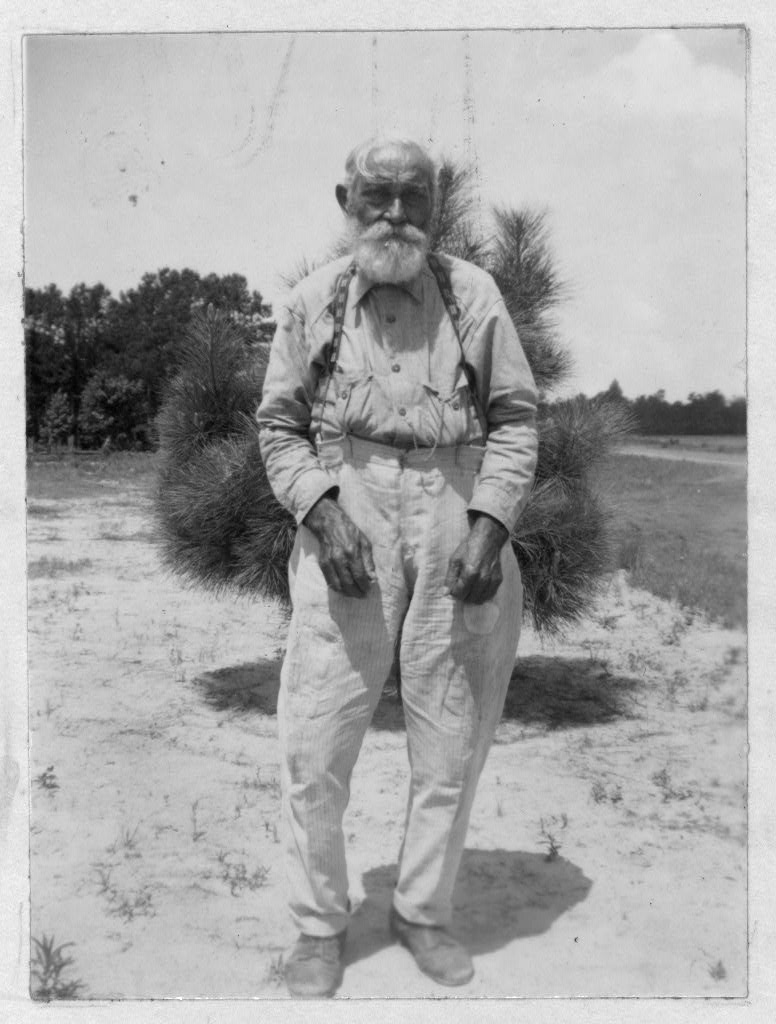

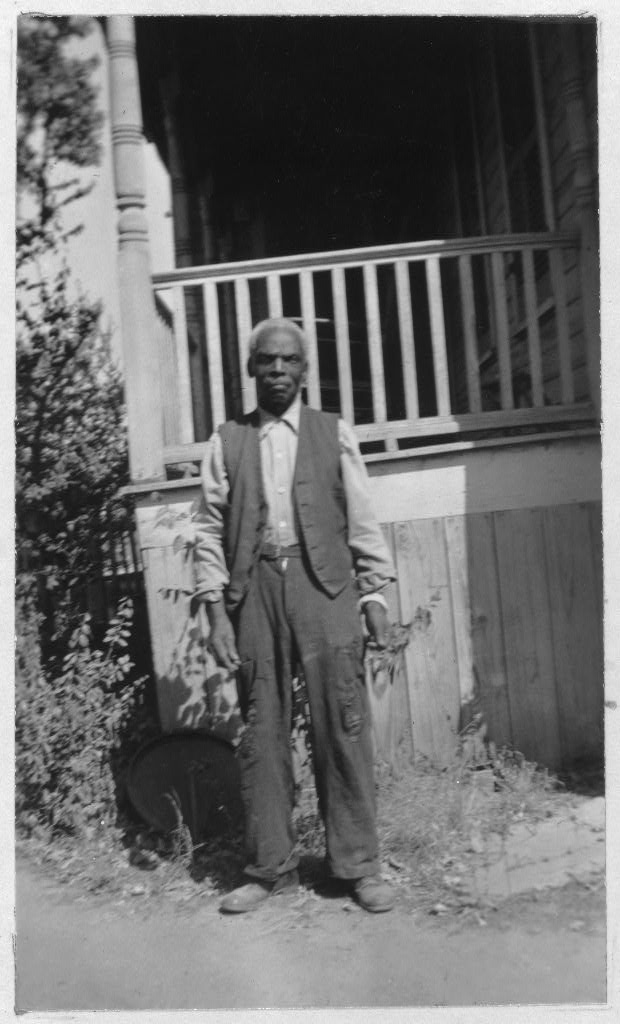

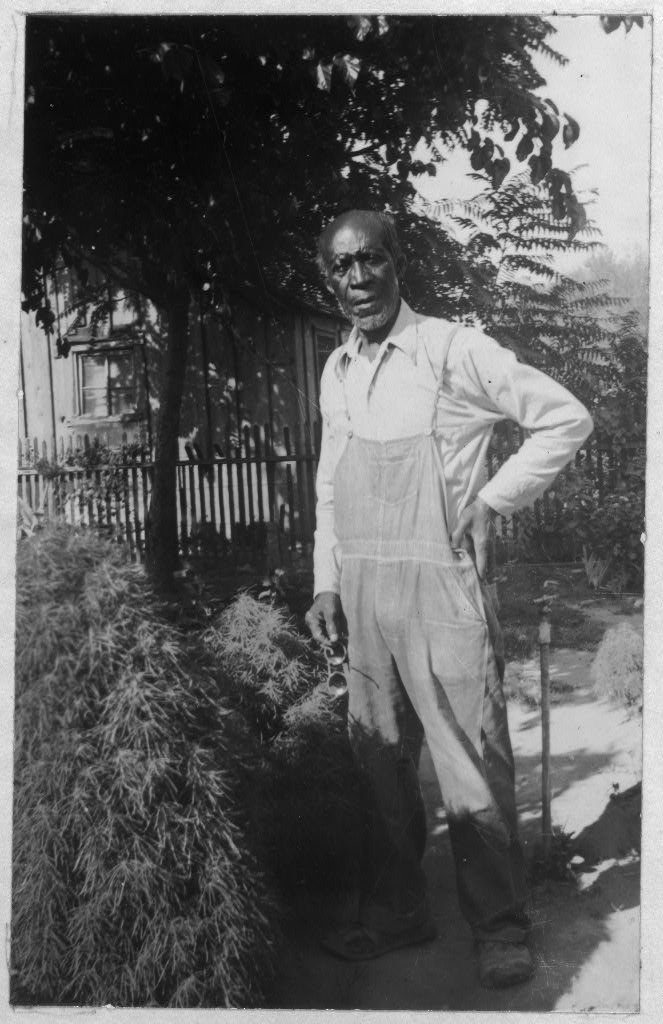

| William Adams | 4 |

| Mary Armstrong | 25 |

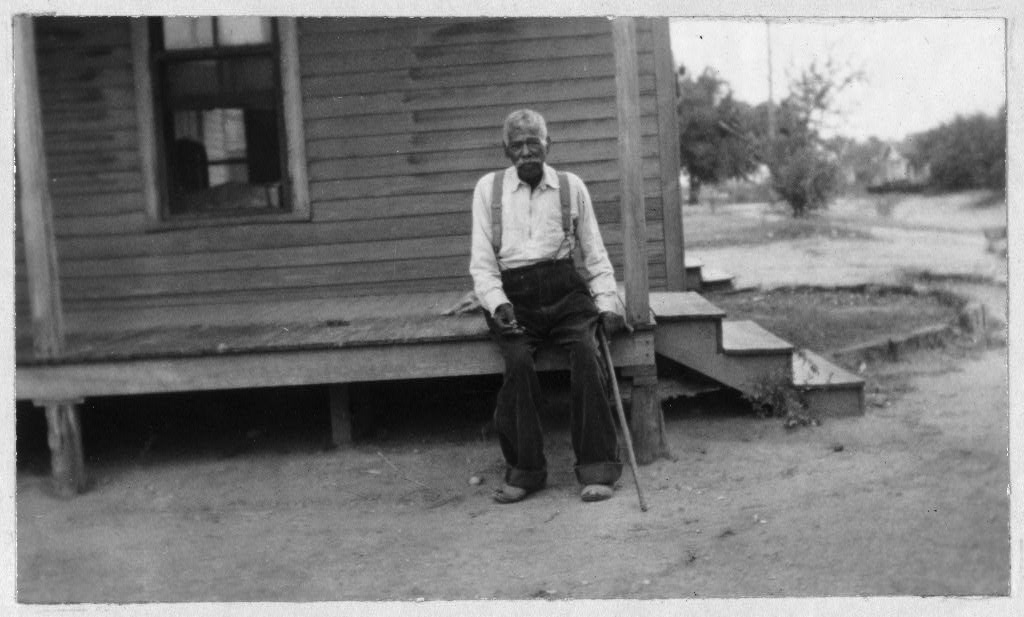

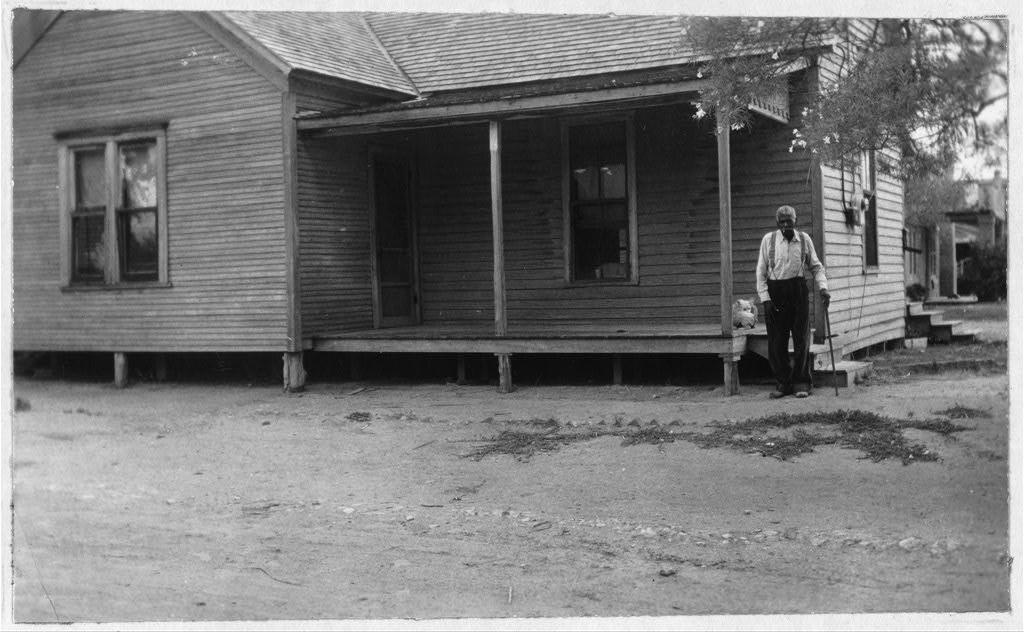

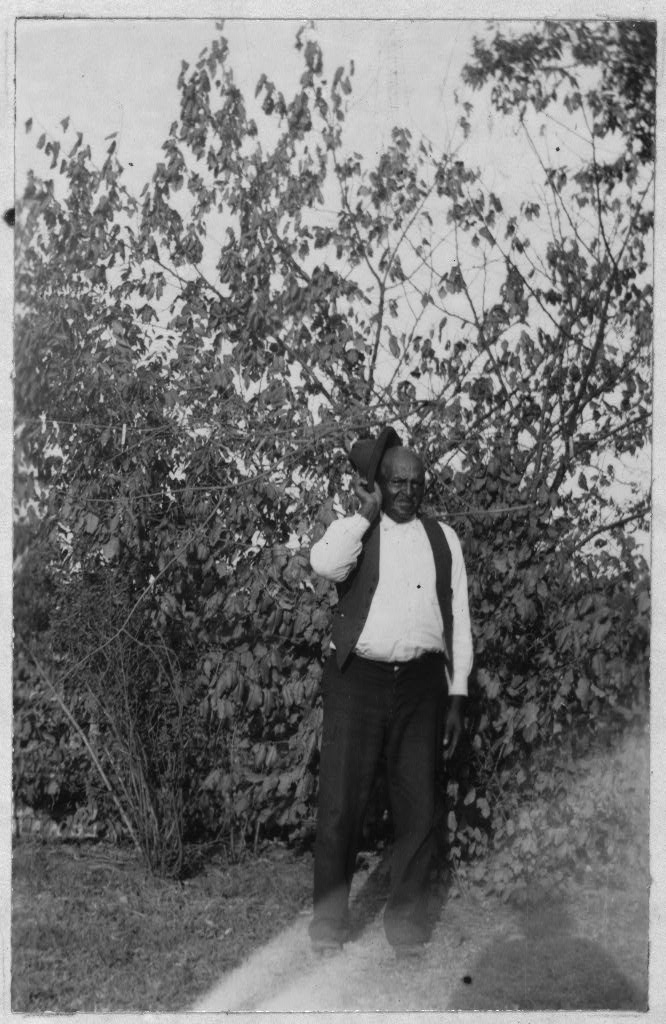

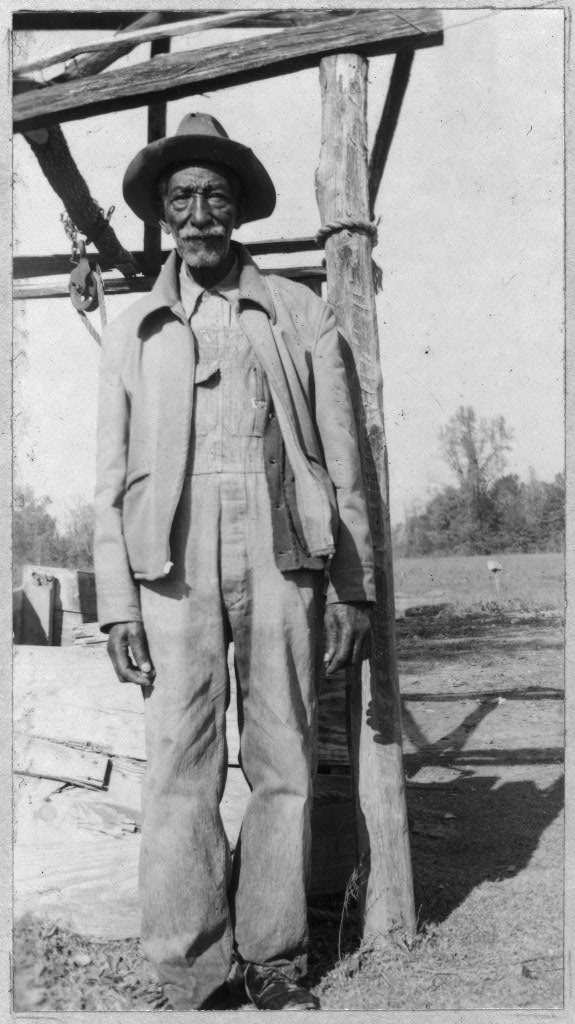

| Sterlin Arnwine | 31 |

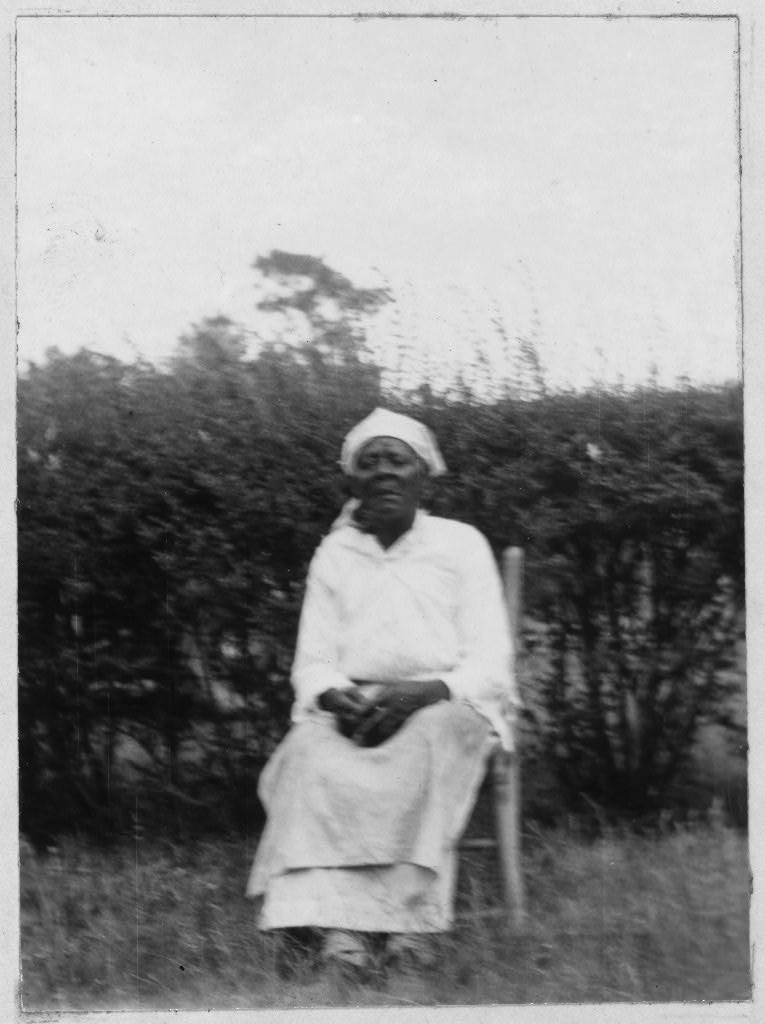

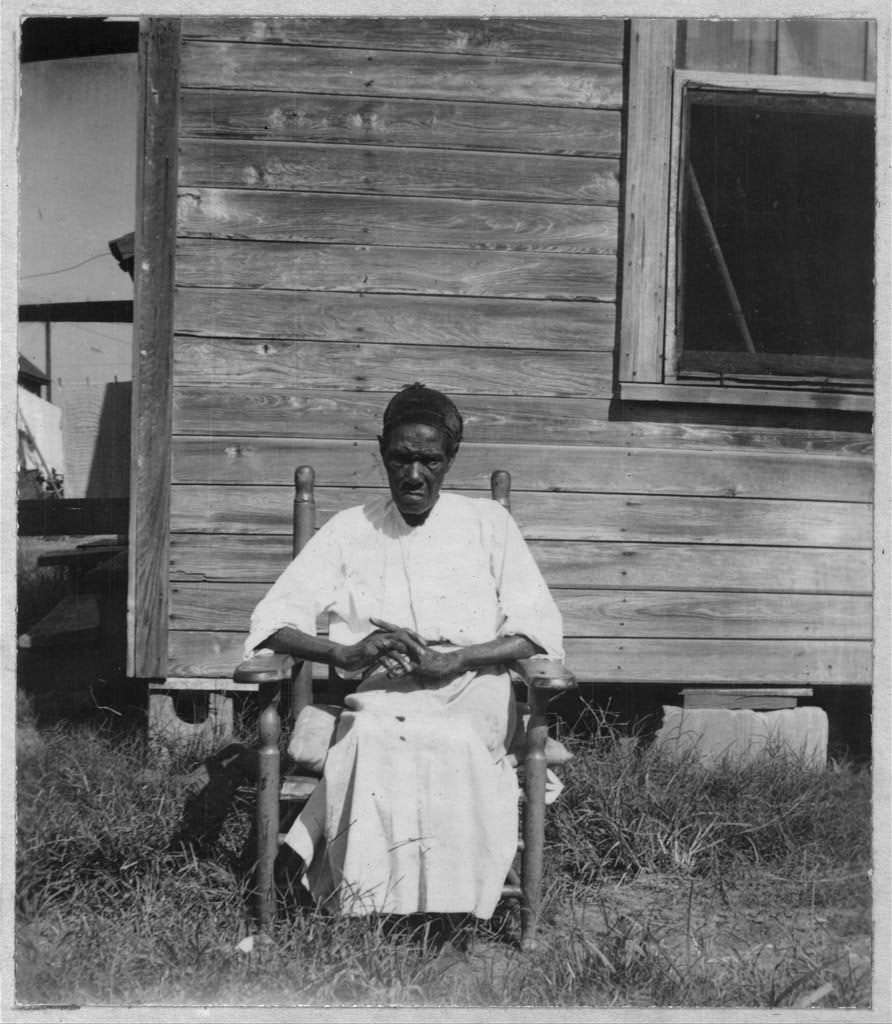

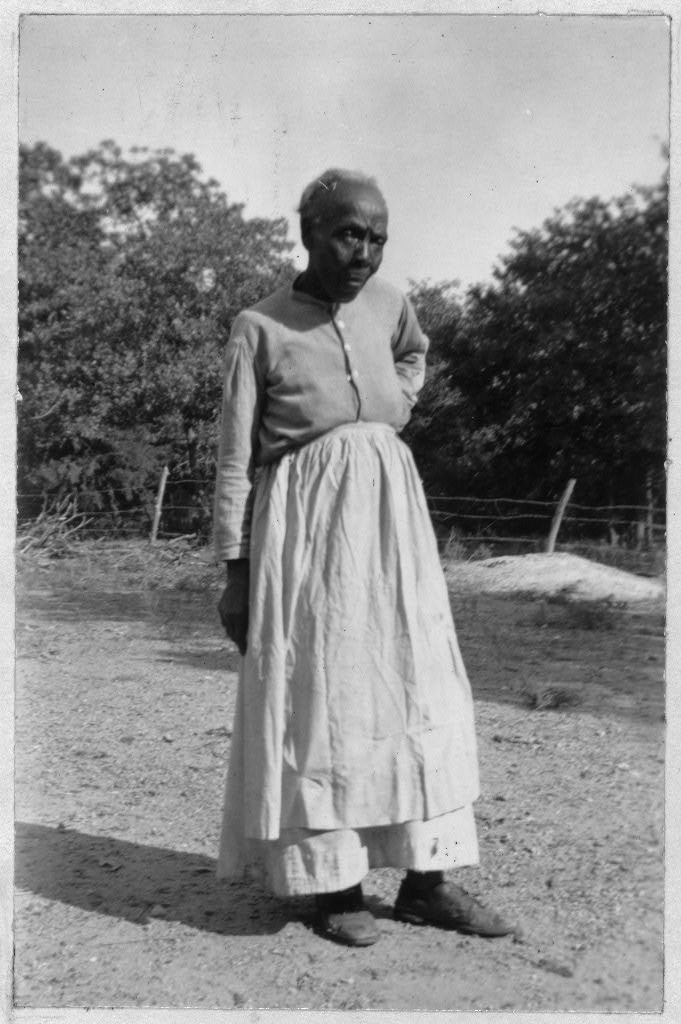

| Sarah Ashley | 34 |

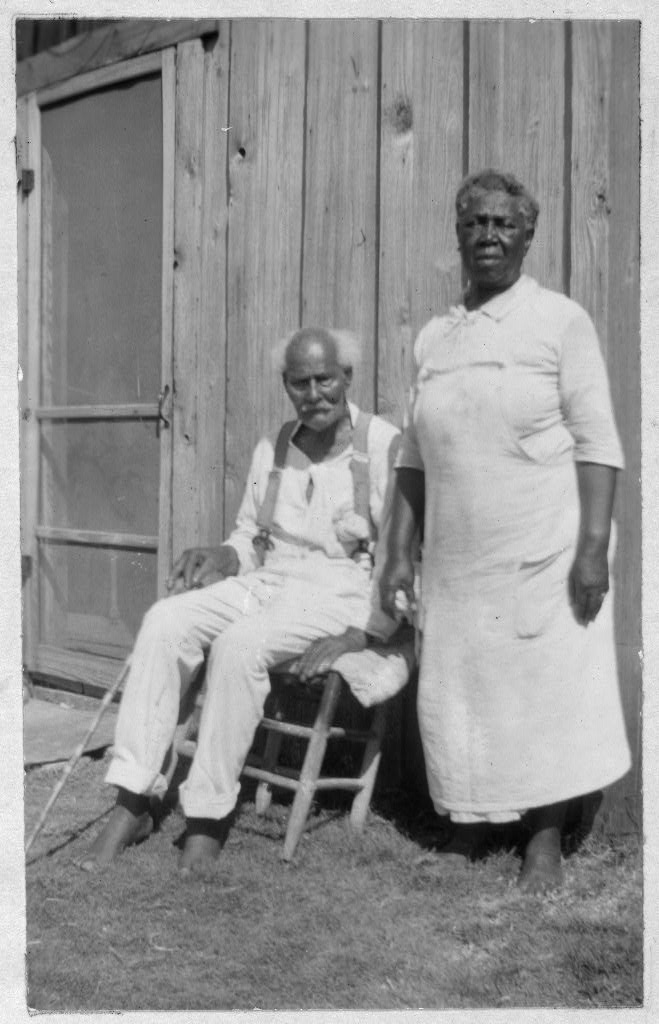

| Edgar and Minerva Bendy | 66 |

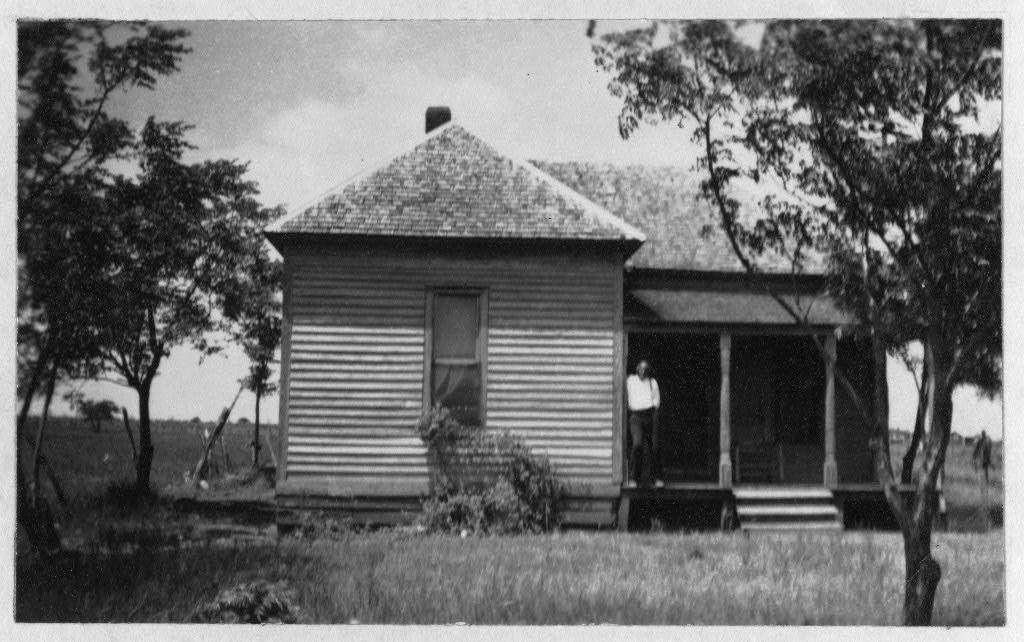

| Jack Bess's House | 72 |

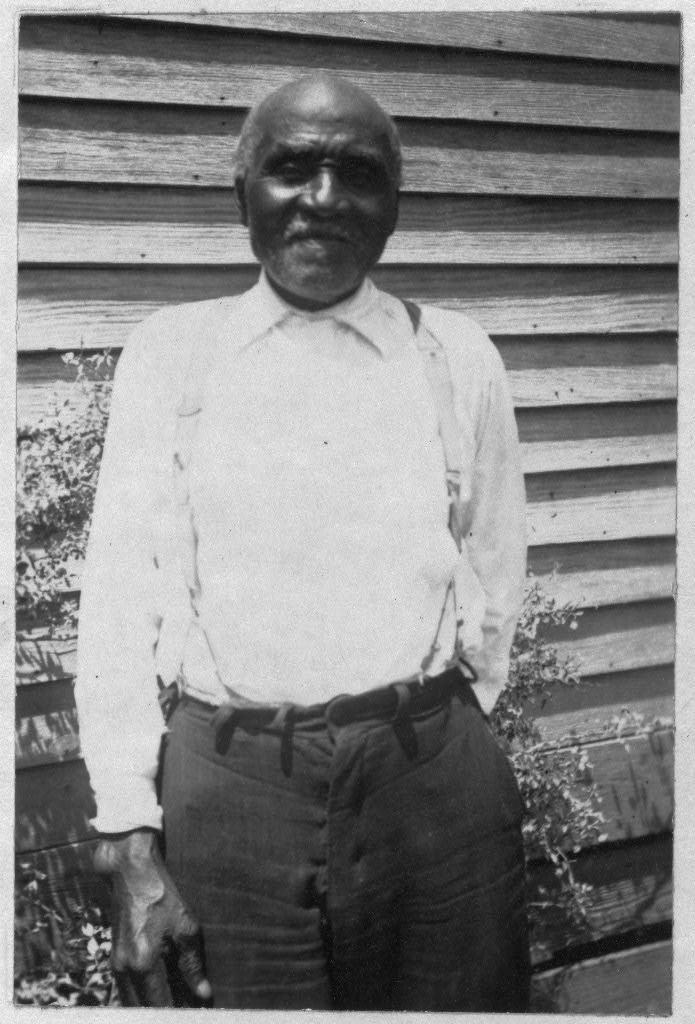

| Jack Bess | 72 |

| Charlotte Beverly | 84 |

| Francis Black | 87 |

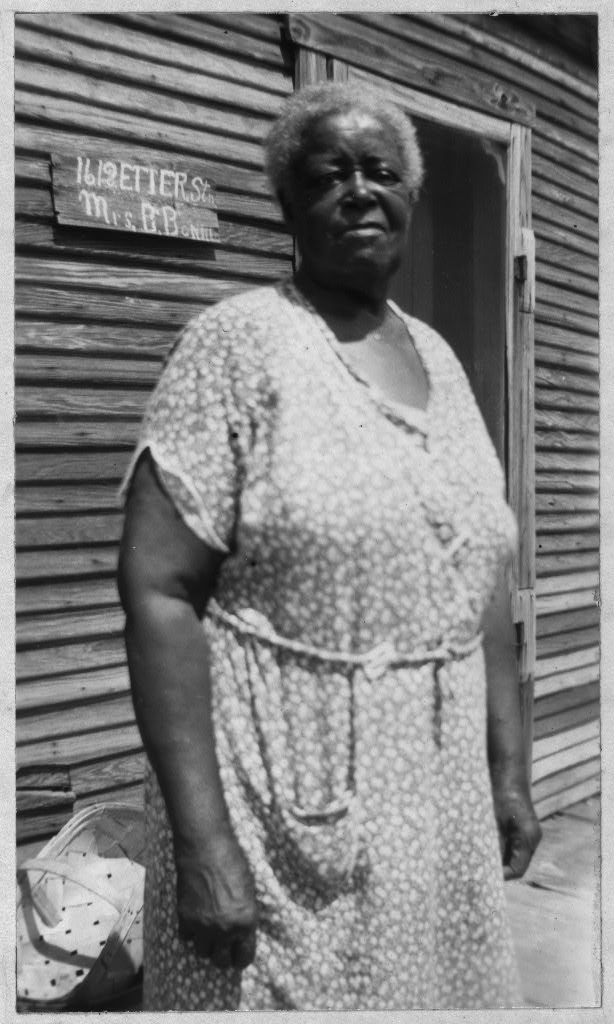

| Betty Bormer (Bonner) | 109 |

| Issabella Boyd | 114 |

| James Boyd | 117 |

| Monroe Brackins | 124 |

| Wes Brady | 133 |

| William Branch | 143 |

| Clara Brim | 147 |

| Sylvester Brooks | 149 |

| Donaville Broussard | 151 |

| Fannie Brown | 154 |

| Fred Brown | 156 |

| James Brown | 160 |

| Josie Brown | 163 |

| Zek Brown | 166 |

| Martha Spence Bunton | 174 |

| Ellen Butler | 176 |

| Simp Campbell | 191 |

| James Cape | 193 |

| Cato Carter | 202 |

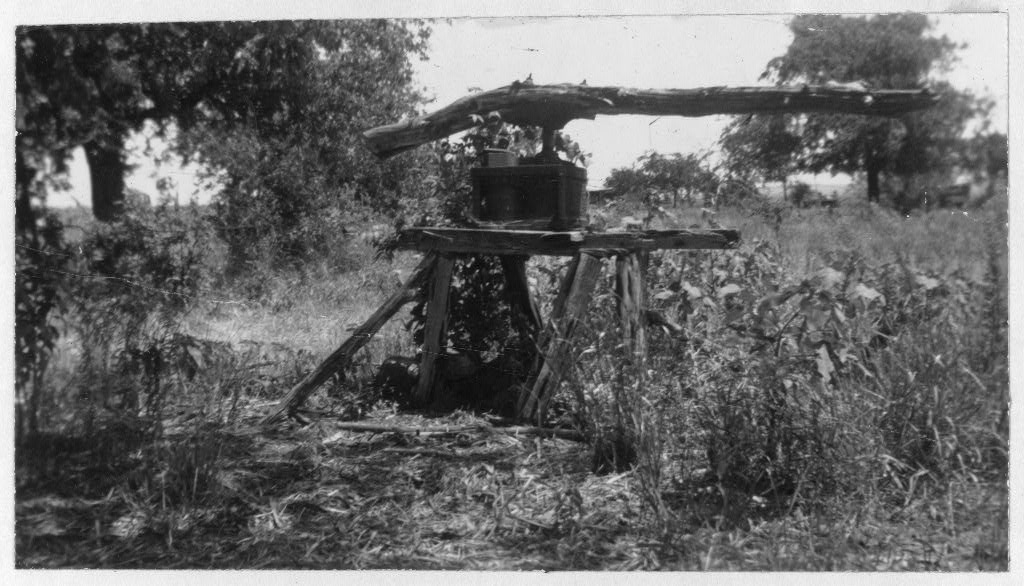

| Amos Clark's Sorghum Mill | 220 |

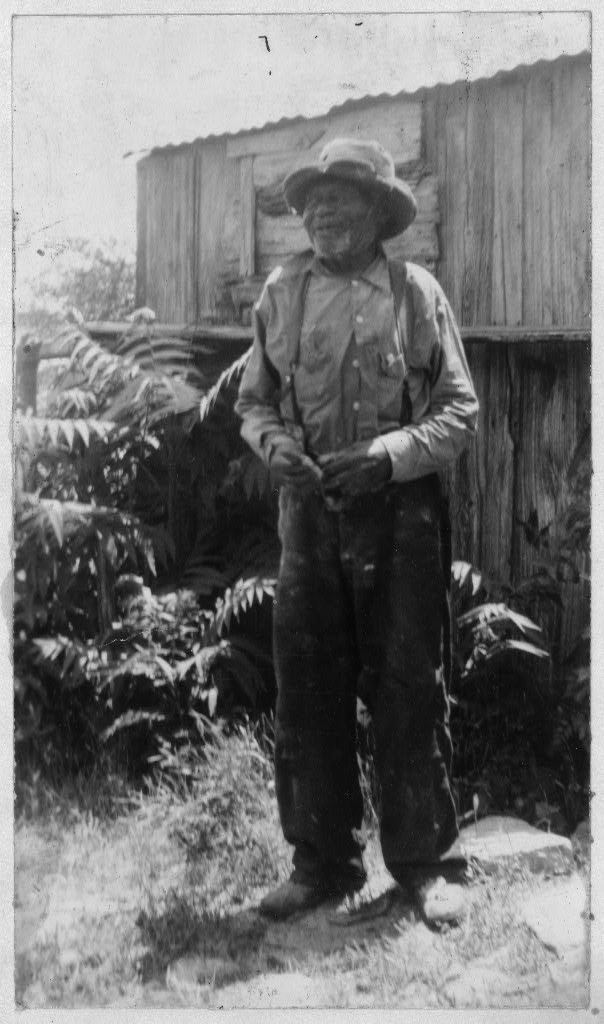

| Amos Clark | 220 |

| Anne Clark | 223 |

| Preely Coleman | 240 |

| Steve Connally | 249 |

| Steve Connally's House | 249 |

| Valmar Cormier | 252 |

| John Crawford | 257 |

| Green Cumby | 260 |

| Tempie Cummins | 263 |

| Adeline Cunningham | 266 |

| Will Daily's House | 269 |

| Will Daily | 269 |

| Julia Francis Daniels | 273 |

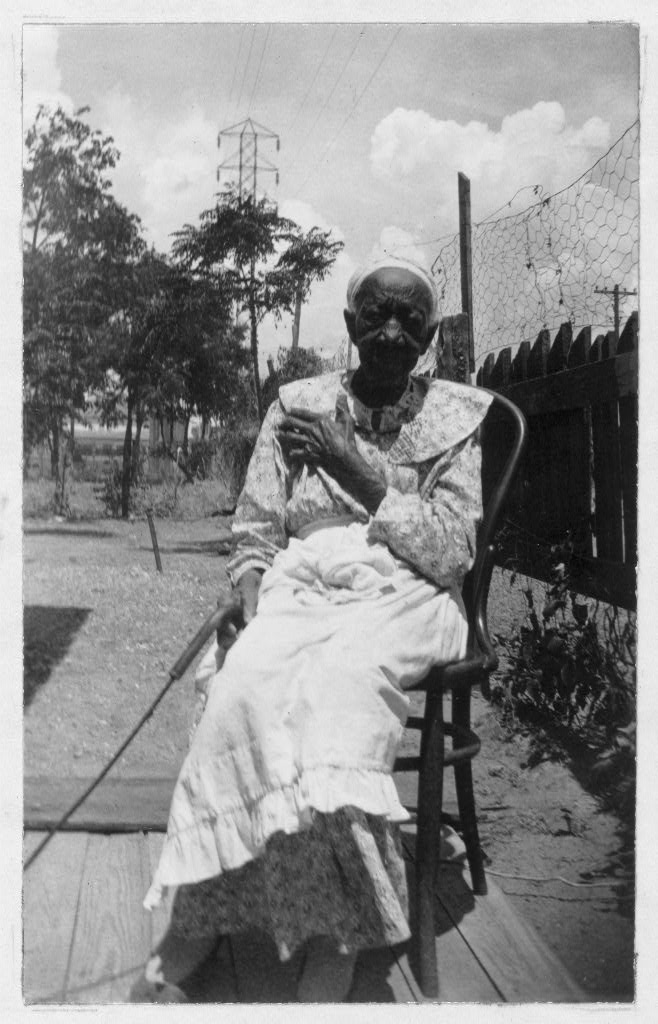

| Katie Darling | 278 |

| Carey Davenport | 281 |

| Campbell Davis | 285 |

| Nelsen Denson | 305 |

WILL ADAMS was born in 1857, a slave of Dave Cavin, in Harrison Co., Texas. He remained with the Cavins until 1885, then farmed for himself. Will lives alone in Marshall, Texas, supported by a $13.00 monthly pension.

"My folks allus belongs to the Cavins and wore their name till after 'mancipation. Pa and ma was named Freeman and Amelia Cavin and Massa Dave fotches them to Texas from Alabama, along with ma's mother, what we called Maria.

"The Cavins allus thunk lots of their niggers and Grandma Maria say, 'Why shouldn't they—it was their money.' She say there was plenty Indians here when they settled this country and they bought and traded with them without killin' them, if they could. The Indians was poor folks, jus' pilfer and loaf 'round all the time. The niggers was a heap sight better off than they was, 'cause we had plenty to eat and a place to stay.

"Young Massa Tom was my special massa and he still lives here. Old Man Dave seemed to think more of his niggers than anybody and we thunk lots of our white folks. My pa was leader on the farm, and there wasn't no overseer or driver. When pa whip a nigger he needn't go to Massa Dave, but pa say, 'Go you way, you nigger. Freeman didn't whip you for nothin'.' Massa Dave allus believe pa, 'cause he tells the truth.

"One time a peddler come to our house and after supper he goes to see 'bout his pony. Pa done feed that pony fifteen ears of corn. The peddler tell massa his pony ain't been fed nothin', and massa git mad and say, 'Be on you way iffen you gwine 'cuse my niggers of lyin'.'[Pg 2]

"We had good quarters and plenty to eat. I 'members when I's jus' walkin' round good pa come in from the field at night and taken me out of bed and dress me and feed me and then play with me for hours. Him bein' leader, he's gone from 'fore day till after night. The old heads got out early but us young scraps slep' till eight or nine o'clock, and don't you think Massa Dave ain't comin' round to see we is fed. I 'members him like it was yest'day, comin' to the quarters with his stick and askin' us, 'Had your breakfas'?' We'd say, 'Yes, suh.' Then he'd ask if we had 'nough or wanted any more. It look like he taken a pleasure in seein' us eat. At dinner, when the field hands come in, it am the same way. He was sho' that potlicker was fill as long as the niggers want to eat.

"The hands worked from sun to sun. Massa give them li'l crops and let them work them on Saturday. Then he bought the stuff and the niggers go to Jefferson and buy clothes and sech like. Lots saved money and bought freedom 'fore the war was over.

"We went to church and first the white preacher preached and then he larns our cullud preachers. I seed him ordain a cullud preacher and he told him to allus be honest. When the white preacher laid his hand on him, all the niggers git to hollerin' and shoutin' and prayin' and that nigger git scart mos' to death.

"On Christmas we had all we could eat and drink and after that a big party, and you ought to see them gals swingin' they partners round. Then massa have two niggers wrestle, and our sports and dances was big sport for the white folks. They'd sit on the gallery and watch the niggers put it on brown.[Pg 3]

"Massa didn't like his niggers to marry off the place, but sometimes they'd do it, and massa tell his neighbor, 'My nigger am comin' to you place. Make him behave.' All the niggers 'haved then and they wasn't no Huntsville and gallows and burnin's then.

"Old massa went to war with his boy, Billie. They's lots of cryin' and weepin' when they sot us free. Lots of them didn't want to be free, 'cause they knowed nothin' and had nowhere to go. Them what had good massas stayed right on.

"I 'members when that Ku Klux business starts up. Smart niggers causes that. The carpet-baggers ruint the niggers and the white men couldn't do a thing with them, so they got up the Ku Klux and stirs up the world. Them carpet-baggers come round larnin' niggers to sass the white folks what done fed them. They come to pa with that talk and he told them, 'Listen, white folks, you is gwine start a graveyard if you come round here teachin' niggers to sass white folks." Them carpet-baggers starts all the trouble at 'lections in Reconstruction. Niggers didn't know anythin' 'bout politics.

"Mos' the young niggers ain't usin' the education they got now. I's been here eighty years and still has to be showed and told by white folks. These young niggers won't git told by whites or blacks either. They thinks they done knowed it all and that gits them in trouble.

"I stays with the Cavins mos' twenty years after the war. After I leaves, I allus farms and does odd jobs round town here. I's father of ten chillen by one woman. I lives by myself now and they gives me $13.00 a month. I'd be proud to git it if it wasn't more'n a dollar, 'cause they ain't nothin' a old man can do no more.[Pg 4]

WILLIAM ADAMS, 93, was born in slavery, with no opportunity for an education, except three months in a public school. He has taught himself to read and to write. His lifelong ambition has been to become master of the supernatural powers which he believes to exist. He is now well-known among Southwestern Negroes for his faith in the occult.

"Yous want to know and talk about de power de people tells you I has. Well, sit down here, right there in dat chair, befo' we'uns starts. I gits some ice water and den we'uns can discuss de subject. I wants to 'splain it clearly, so yous can understand.

"I's born a slave, 93 years ago, so of course I 'members de war period. Like all de other slaves I has no chance for edumacation. Three months am de total time I's spent going to school. I teached myself to read and write. I's anxious to larn to read so I could study and find out about many things. Dat, I has done.

"There am lots of folks, and edumacated ones, too, what says we'uns believes in superstition. Well, its 'cause dey don't understand. 'Member de Lawd, in some of His ways, can be mysterious. De Bible says so. There am some things de Lawd wants all folks to know, some things jus' de chosen few to know, and some things no one should know. Now, jus' 'cause yous don't know 'bout some of de Lawd's laws, 'taint superstition if some other person understands and believes in sich.

"There is some born to sing, some born to preach, and some born to know de signs. There is some born under de power of de devil[Pg 5] and have de power to put injury and misery on people, and some born under de power of de Lawd for to do good and overcome de evil power. Now, dat produces two forces, like fire and water. De evil forces starts de fire and I has de water force to put de fire out.

"How I larnt sich? Well, I's done larn it. It come to me. When de Lawd gives sich power to a person, it jus' comes to 'em. It am 40 years ago now when I's fust fully realize' dat I has de power. However, I's allus int'rested in de workin's of de signs. When I's a little piccaninny, my mammy and other folks used to talk about de signs. I hears dem talk about what happens to folks 'cause a spell was put on 'em. De old folks in dem days knows more about de signs dat de Lawd uses to reveal His laws den de folks of today. It am also true of de cullud folks in Africa, dey native land. Some of de folks laughs at their beliefs and says it am superstition, but it am knowin' how de Lawd reveals His laws.

"Now, let me tell yous of something I's seen. What am seen, can't be doubted. It happens when I's a young man and befo' I's realize' dat I's one dat am chosen for to show de power. A mule had cut his leg so bad dat him am bleedin' to death and dey couldn't stop it. An old cullud man live near there dat dey turns to. He comes over and passes his hand over de cut. Befo' long de bleedin' stop and dat's de power of de Lawd workin' through dat nigger, dat's all it am.

"I knows about a woman dat had lost her mind. De doctor say it was caused from a tumor in de head. Dey took an ex-ray picture, but dere's no tumor. Dey gives up and says its a peculiar case. Dat woman was took to one with de power of de good spirit and he say its a peculiar case for dem dat don't understand. Dis am a case of de evil spell. Two days after, de[Pg 6] woman have her mind back.

"Dey's lots of dose kind of cases de ord'nary person never hear about. Yous hear of de case de doctors can't understand, nor will dey 'spond to treatment. Dat am 'cause of de evil spell dat am on de persons.

"'Bout special persons bein' chosen for to show de power, read yous Bible. It says in de book of Mark, third chapter, 'and He ordained twelve, dat dey should be with Him, dat He might send them forth to preach and to have de power to heal de sick and to cast out devils.' If it wasn't no evil in people, why does de Lawd say, 'cast out sich?' And in de fifth chapter of James, it further say, 'If any am sick, let him call de elders. Let dem pray over him. De prayers of faith shall save him.' There 'tis again, Faith, dat am what counts.

"When I tells dat I seen many persons given up to die, and den a man with de power comes and saves sich person, den its not for people to say it am superstition to believe in de power.

"Don't forgit—de agents of de devil have de power of evil. Dey can put misery of every kind on people. Dey can make trouble with de work and with de business, with de fam'ly and with de health. So folks mus' be on de watch all de time. Folks has business trouble 'cause de evil power have control of 'em. Dey has de evil power cast out and save de business. There am a man in Waco dat come to see me 'bout dat. He say to me everything he try to do in de las' six months turned out wrong. It starts with him losin' his pocketbook with $50.00 in it. He buys a carload of hay and it catch fire and he los' all of it. He spends[Pg 7] $200.00 advertisin' de three-day sale and it begin to rain, so he los' money. It sho' am de evil power.

"'Well,' he say, 'Dat am de way it go, so I comes to you.'

"I says to him, 'Its de evil power dat have you control and we'uns shall cause it to be cast out.' Its done and he has no more trouble.

"You wants to know if persons with de power for good can be successful in castin' out devils in all cases? Well, I answers dat, yes and no. Dey can in every case if de affected person have de faith. If de party not have enough faith, den it am a failure.

"Wearin' de coin for protection 'gainst de evil power? Dat am simple. Lots of folks wears sich and dey uses mixtures dat am sprinkled in de house, and sich. Dat am a question of faith. If dey has de true faith in sich, it works. Otherwise, it won't.

"Some folks won't think for a minute of goin' without lodestone or de salt and pepper mixture in de little sack, tied round dey neck. Some wears de silver coin tied round dey neck. All sich am for to keep away de effect of de evil power. When one have de faith in sich and dey acc'dently lose de charm, dey sho' am miserable.

"An old darky dat has faith in lodestone for de charm told me de 'sperience he has in Atlanta once. He carryin' de hod and de fust thing he does am drop some brick on he foot. De next thing, he foot slip as him starts up de ladder and him and de bricks drap to de ground. It am lucky for him it wasn't far. Jus' a sprain ankle and de boss sends him home for de day. He am 'cited and gits on de street car and when de conductor call for de fare, Rufus reaches for he money[Pg 8] but he los' it or fergits it at home. De conductor say he let him pay nex' time and asks where he live. Rufus tells him and he say, 'Why, nigger, you is on de wrong car.' Dat cause Rufus to walk further with de lame foot dan if he started walkin' in de fust place. He thinks there mus' be something wrong with he charm, and he look for it and it gone! Sho' 'nough, it am los'. He think, 'Here I sits all day, and I won't make another move till I gits de lodestone. When de chillen comes from school I sends dem to de drugstore for some of de stone and gits fixed.'

"Now, now, I's been waitin' for dat one 'bout de black cat crossin' de road, and, sho' 'nough, it come. Let me ask you one. How many people can yous find dat likes to have de black cat cross in front of 'em? Dat's right, no one likes dat. Let dis old cullud person inform yous dat it am sho' de bad luck sign. It is sign of bad luck ahead, so turn back. Stop what yous doin'.

"I's tellin' yous of two of many cases of failure to took warnin' from de black cat. I knows a man call' Miller. His wife and him am takin' an auto ride and de black cat cross de road and he cussed a little and goes on. Den it's not long till he turns de corner and his wife falls out of de car durin' de turn. When he goes back and picks her up, she am dead.

"Another fellow, call' Brown, was a-ridin' hossback and a black cat cross de path, but he drives on. Well, its not long till him hoss stumble and throw him off. De fall breaks his leg, so take a warnin'—don't overlook de black cat. Dat am a warnin'.[Pg 9]

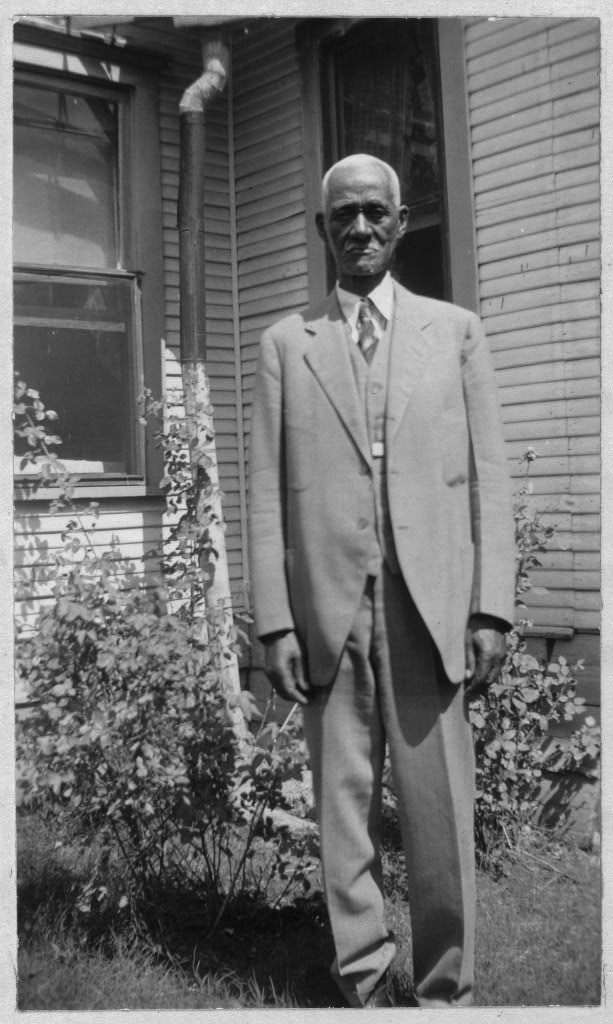

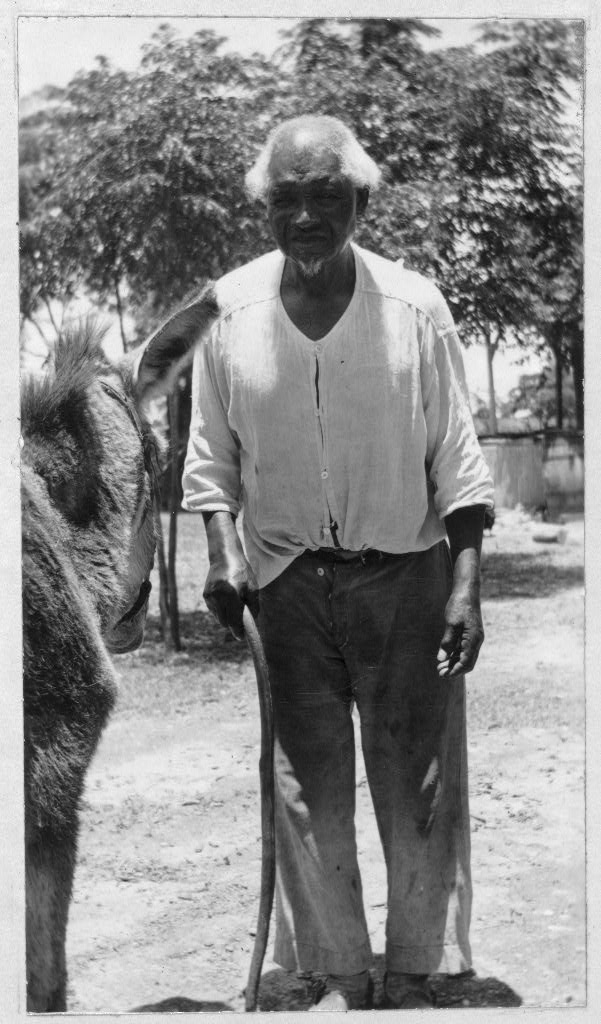

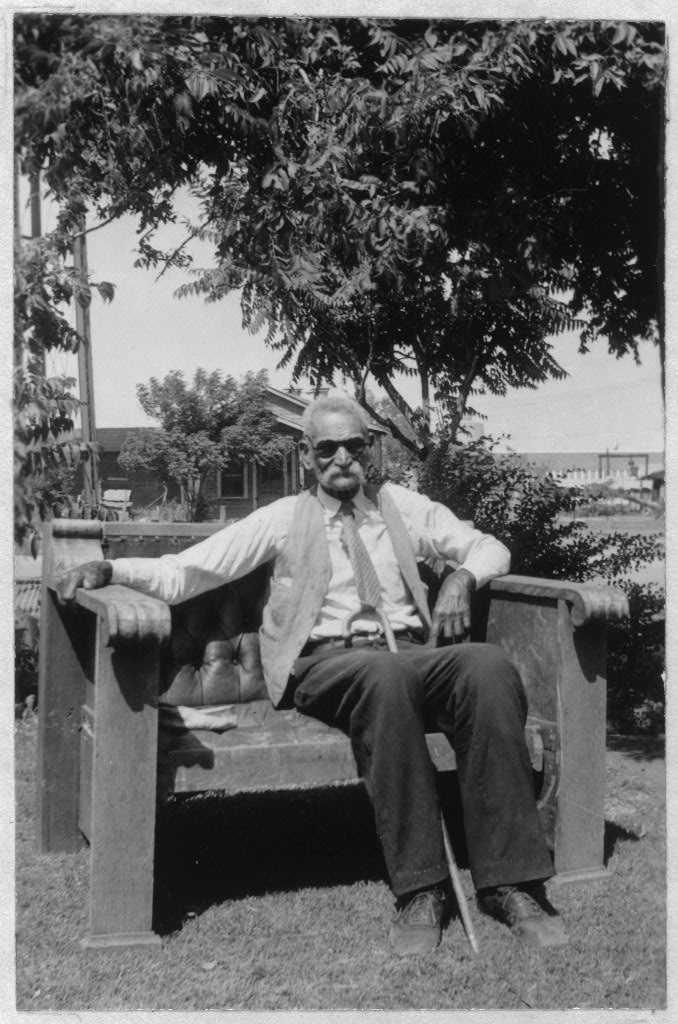

WILLIAM M. ADAMS, spiritualist preacher and healer, who lives at 1404 Illinois Ave., Ft. Worth, Texas, was born a slave on the James Davis plantation, in San Jacinto Co., Texas. After the war he worked in a grocery, punched cattle, farmed and preached. He moved to Ft. Worth in 1902.

"I was bo'n 93 years ago, dat is whut my mother says. We didn' keep no record like folks does today. All I know is I been yere a long time. My mother, she was Julia Adams and my father he was James Adams. She's bo'n in Hollis Springs, Mississippi and my father, now den, he was bo'n in Florida. He was a Black Creek Indian. Dere was 12 of us chillen. When I was 'bout seven de missus, she come and gits me for her servant. I lived in de big house till she die. Her and Marster Davis was powerful good to me.

"Marster Davis he was a big lawyer and de owner of a plantation. But all I do was wait on ole missus. I'd light her pipe for her and I helped her wid her knittin'. She give me money all de time. She had a little trunk she keeped money in and lots of times I'd have to pack it down wid my feets.

"I dis'member jus' how many slaves dere was, but dere was more'n 100. I saw as much as 100 sold at a time. When dey tuk a bunch of slaves to trade, dey put chains on 'em.

"De other slaves lived in log cabins back of de big house. Dey had dirt floors and beds dat was made out of co'n shucks or straw. At nite dey burned de lamps for 'bout an hour, den de overseers,[Pg 10] dey come knock on de door and tell 'em put de light out. Lots of overseers was mean. Sometimes dey'd whip a nigger wid a leather strap 'bout a foot wide and long as your arm and wid a wooden handle at de end.

"On Sat'day and Sunday nites dey'd dance and sing all nite long. Dey didn' dance like today, dey danced de roun' dance and jig and do de pigeon wing, and some of dem would jump up and see how many time he could kick his feets 'fore dey hit de groun'. Dey had an ole fiddle and some of 'em would take two bones in each hand and rattle 'em. Dey sang songs like, 'Diana had a Wooden Leg,' and 'A Hand full of Sugar,' and 'Cotton-eyed Joe.' I dis'member how dey went.

"De slaves didn' have no church den, but dey'd take a big sugar kettle and turn it top down on de groun' and put logs roun' it to kill de soun'. Dey'd pray to be free and sing and dance.

"When war come dey come and got de slaves from all de plantations and tuk 'em to build de breastworks. I saw lots of soldiers. Dey'd sing a song dat go something like dis:

"'Jeff Davis rode a big white hoss,

Lincoln rode a mule;

Jess Davis is our President,

Lincoln is a fool.'

"I 'member when de slaves would run away. Ole John Billinger, he had a bunch of dogs and he'd take after runaway niggers. Sometimes de dogs didn' ketch de nigger. Den ole Billinger, he'd cuss and kick de dogs.

"We didn' have to have a pass but on other plantations dey did, or de paddlerollers would git you and whip you. Dey was de poor white[Pg 11] folks dat didn' have no slaves. We didn' call 'em white folks dem days. No, suh, we called dem' Buskrys.'

"Jus' fore de war, a white preacher he come to us slaves and says: 'Do you wan' to keep you homes whar you git all to eat, and raise your chillen, or do you wan' to be free to roam roun' without a home, like de wil' animals? If you wan' to keep you homes you better pray for de South to win. All day wan's to pray for de South to win, raise the hand.' We all raised our hands 'cause we was skeered not to, but we sho' didn' wan' de South to win.

"Dat night all de slaves had a meetin' down in de hollow. Ole Uncle Mack, he gits up and says: 'One time over in Virginny dere was two ole niggers, Uncle Bob and Uncle Tom. Dey was mad at one 'nuther and one day dey decided to have a dinner and bury de hatchet. So day sat down, and when Uncle Bob wasn't lookin' Uncle Tom put some poison in Uncle Bob's food, but he saw it and when Uncle Tom wasn't lookin', Uncle Bob he turned de tray roun' on Uncle Tom, and he gits de poison food.' Uncle Mack, he says: 'Dat's what we slaves is gwine do, jus' turn de tray roun' and pray for de North to win.'

"After de war dere was a lot of excitement 'mong de niggers. Dey was rejoicin' and singin'. Some of 'em looked puzzled, sorter skeered like. But dey danced and had a big jamboree.

"Lots of 'em stayed and worked on de halves. Others hired out. I went to work in a grocery store and he paid me $1.50 a week. I give my mother de dollar and keeped de half. Den I got married and farmed for awhile. Den I come to Fort Worth and I been yere since.[Pg 12]

SARAH ALLEN was born a slave of John and Sally Goodren, in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. Before the Civil War, her owners came to Texas, locating near a small town then called Freedom. She lives at 3322 Frutas St., El Paso, Texas.

"I was birthed in time of bondage. You know, some people are ashamed to tell it, but I thank God I was 'llowed to see them times as well as now. It's a pretty hard story, how cruel some of the marsters was, but I had the luck to be with good white people. But some I knew were put on the block and sold. I 'member when they'd come to John Goodren's place to buy, but he not sell any. They'd have certain days when they'd sell off the block and they took chillen 'way from mothers, screamin' for dere chillen.

"I was birthed in ole Virginia in de Blue Ridge Mountains. When de white people come to Texas, de cullud people come with them. Dat's been a long time.

"My maw was named Charlotte, my paw Parks Adams. He's a white man. I guess I'm about eighty some years ole.

"You know, in slavery times when dey had bad marsters dey'd run away, but we didn' want to. My missus would see her people had something good to eat every Sunday mornin'. You had to mind your missus and marster and you be treated well. I think I was about twelve when dey freed us and we stayed with marster 'bout a year, then went to John Ecols' place and rented some lan'. We made two bales of cotton and it was the first money we ever saw.

"Back when we lived with Marster Goodren we had big candy[Pg 13] pullin's. Invite everybody and play. We had good times. De worst thing, we didn' never have no schoolin' till after I married. Den I went to school two weeks. My husban' was teacher. He never was a slave. His father bought freedom through a blacksmith shop, some way.

"I had a nice weddin'. My dress was white and trimmed with blue ribbon. My second day dress was white with red dots. I had a beautiful veil and a wreath and 'bout two, three waiters for table dat day.

"My mother was nearly white. Brighter than me. We lef' my father in Virginia. I was jus' as white as de chillen I played with. I used to be plum bright, but here lately I'm gettin' awful dark.

"My husban' was of a mixture, like you call bright ginger-cake color. I don' know where he got his learnin'. I feel so bad since he's gone to Glory.

"Now I'm ole, de Lord has taken care of me. He put that spirit in people to look after ole folks and now my chillen look after me. I've two sons, one name James Allen, one R.M. Both live in El Paso.

"After we go to sleep, de people will know these things, 'cause if freedom hadn' come, it would have been so miserable.[Pg 14]

ANDY ANDERSON, 94, was born a slave of Jack Haley, who owned a plantation in Williamson Co., Texas. During the Civil War, Andy was sold to W.T. House, of Blanco County, who in less than a year sold Andy to his brother, John House. Andy now lives with his third wife and eight of his children at 301 Armour St., Fort Worth, Texas.

"My name am Andy J. Anderson, and I's born on Massa Jack Haley's plantation in Williamson County, Texas, and Massa Haley owned my folks and 'bout twelve other families of niggers. I's born in 1843 and that makes me 94 year old and 18 year when de war starts. I's had 'speriences durin' dat time.

"Massa Haley am kind to his cullud folks, and him am kind to everybody, and all de folks likes him. De other white folks called we'uns de petted niggers. There am 'bout 30 old and young niggers and 'bout 20 piccaninnies too little to work, and de nuss cares for dem while dey mammies works.

"I's gwine 'splain how it am managed on Massa Haley's plantation. It am sort of like de small town, 'cause everything we uses am made right there. There am de shoemaker and he is de tanner and make de leather from de hides. Den massa has 'bout a thousand sheep and he gits de wool, and de niggers cards and spins and weaves it, and dat makes all de clothes. Den massa have cattle and sich purvide de milk and de butter and beef meat for eatin'. Den massa have de turkeys and chickens and de hawgs and de bees. With all that, us never was hongry.

"De plantation am planted in cotton, mostly, with de corn and de wheat a little, 'cause massa don't need much of dem. He never sell nothin' but de cotton.[Pg 15]

"De livin' for de cullud folks am good. De quarters am built from logs like deys all in dem days. De floor am de dirt but we has de benches and what is made on de place. And we has de big fireplace for to cook and we has plenty to cook in dat fireplace, 'cause massa allus 'lows plenty good rations, but he watch close for de wastin' of de food.

"De war breaks and dat make de big change on de massas place. He jines de army and hires a man call' Delbridge for overseer. After dat, de hell start to pop, 'cause de first thing Delbridge do is cut de rations. He weighs out de meat, three pound for de week, and he measure a peck of meal. And 'twarn't enough. He half starve us niggers and he want mo' work and he start de whippin's. I guesses he starts to edumacate 'em. I guess dat Delbridge go to hell when he died, but I don't see how de debbil could stand him.

"We'uns am not use' to sich and some runs off. When dey am cotched there am a whippin' at de stake. But dat Delbridge, he sold me to Massa House, in Blanco County. I's sho' glad when I's sold, but it am short gladness, 'cause here am another man what hell am too good for. He gives me de whippin' and de scars am still on my arms and my back, too. I'll carry dem to my grave. He sends me for firewood and when I gits it loaded, de wheel hits a stump and de team jerks and dat breaks de whippletree. So he ties me to de stake and every half hour for four hours, dey lays ta lashes on my back. For de first couple hours de pain am awful. I's never forgot it. Den I's stood so much pain I not feel so much and when dey takes me loose, I's jus' 'bout half dead. I lays in de bunk two days, gittin' over dat whippin', gittin' over it in de body but not de heart. No, suh, I has dat in de heart till dis day.[Pg 16]

"After dat whippin' I doesn't have de heart to work for de massa. If I seed de cattle in de cornfield, I turns de back, 'stead of chasin' 'em out. I guess dat de reason de massa sold me to his brother, Massa John. And he am good like my first massa, he never whipped me.

"Den surrender am 'nounced and massa tells us we's free. When dat takes place, it am 'bout one hour by sun. I says to myself, 'I won't be here long.' But I's not realise what I's in for till after I's started, but I couldn't turn back. For dat means de whippin' or danger from de patter rollers. Dere I was and I kep' on gwine. No nigger am sposed to be off de massa's place without de pass, so I travels at night and hides durin' de daylight. I stays in de bresh and gits water from de creeks, but not much to eat. Twice I's sho' dem patter rollers am passin' while I's hidin'.

"I's 21 year old den, but it am de first time I's gone any place, 'cept to de neighbors, so I's worried 'bout de right way to Massa Haley's place. But de mornin' of de third day I comes to he place and I's so hongry and tired and scairt for fear Massa Haley not home from de army yit. So I finds my pappy and he hides me in he cabin till a week and den luck comes to me when Massa Haley come home. He come at night and de next mornin' dat Delbridge am shunt off de place, 'cause Massa Haley seed he niggers was all gaunt and lots am ran off and de fields am not plowed right, and only half de sheep and everything left. So massa say to dat Delbridge, 'Dere am no words can 'splain what yous done. Git off my place 'fore I smashes you.'

"Den I kin come out from my pappy's cabin and de old massa was glad to see me, and he let me stay till freedom am ordered. Dat's de happies' time in my life, when I gits back to Massa Haley.[Pg 17]

Dibble, Fred, P.W., Beehler, Rheba, P.W., Beaumont, Jefferson, Dist. #3.

A frail sick man, neatly clad in white pajamas lying patiently in a clean bed awaiting the end which does not seem far away. Although we protested against his talking, because of his weakness, he told a brief story of his life in a whisper, his breath very short and every word was spoken with great effort. His light skin and his features denote no characteristic of his race, has a bald head with a bit of gray hair around the crown and a slight growth of gray whiskers about his face, is medium in height and build. WASH ANDERSON, although born in Charleston, S.C., has spent practically all of his life in Texas [Handwritten Note: (Beaumont, Texas—]

"Mos' folks call me Wash Anderson, but dey uster call me George. My whole name' George Washington Anderson. I was bo'n in Charleston, Sou'f Ca'lina in 1855. Bill Anderson was my ol' marster. Dey was two boy' and two gal' in his family. We all lef' Charleston and come to Orange, Texas, befo' freedom come. I was fo' year' ol' when dey mek dat trip."

"I don' 'member nuttin' 'bout Charleston. You see where I was bo'n was 'bout two mile' from de city. I went back one time in 1917, but I didn' stay dere long."

"My pa was Irvin' Anderson and my mommer was name' Eliza. Ol' marster was pretty rough on his niggers. Dey[Pg 18] tell me he had my gran'daddy beat to death. Dey never did beat me."

"Dey made de trip from Charleston 'cross de country and settle' in Duncan's Wood' down here in Orange county. Dey had a big plantation dere. I dunno if ol' marster had money back in Charleston, but I t'ink he must have. He had 'bout 25 or 30 slaves on de place."

"Ol' man Anderson he had a big two-story house. It was buil' out of logs but it was a big fine house. De slaves jis' had little log huts. Dere warn't no flo's to 'em, nuthin' but de groun'. Dem little huts jis' had one room in 'em. Dey was one family to de house, 'cep'n' sometime dey put two or t'ree family' to a house. Dey jis' herd de slaves in dere like a bunch of pigs."

"Dey uster raise cotton, and co'n, and sugar cane, and sich like, but dey didn' uster raise no rice. Dey uster sen' stuff to Terry on a railroad to sen' it to market. Sometime dey hitch up dey teams and sen' it to Orange and Beaumont in wagons. De ol' marster he had a boat, too, and sometime he sen' a boatload of his stuff to Beaumont."

"My work was to drive de surrey for de family and look atter de hosses and de harness and sich. I jis' have de bes' hosses on de place to see atter."[Pg 19]

"I saw lots of sojers durin' de war. I see 'em marchin' by, goin' to Sabine Pass 'bout de time of dat battle."

"Back in slavery time dey uster have a white preacher to come 'roun' and preach to de cullud folks. But I don't 'member much 'bout de songs what dey uster sing."

"I play 'roun' right smart when I was little. Dey uster have lots of fun playin' 'hide and seek,' and 'hide de switch.' We uster ride stick hosses and play 'roun' at all dem t'ings what chillun play at."

"Dey had plenty of hosses and mules and cows on de ol' plantation. I had to look atter some of de hosses, but dem what I hatter look atter was s'pose to be de bes' hosses in de bunch. Like I say, I drive de surrey and dey allus have de bes' hosses to pull dat surrey. Dey had a log stable. Dey kep' de harness in dere, too. Eb'ryt'ing what de stock eat dey raise on de plantation, all de co'n and fodder and sich like."

"Atter freedom come I went 'roun' doin' dif'rent kind of work. I uster work on steamboats, and on de railroad and at sawmillin'. I was a sawyer for a long, long time. I work 'roun' in Lou'sana and Arkansas, and Oklahoma, as[Pg 20] well as in Texas. When I wasn't doin' dem kinds of work, I uster work 'roun' at anyt'ing what come to han'. I 'member one time I was workin' for de Burr Lumber Company at Fort Townsend up dere in Arkansas."

"When I was 'bout 36 year' ol' I git marry. I been married twice. My fus' wife was name' Hannah and Reverend George Childress was de preacher dat marry us. He was a cullud preacher. Atter Hannah been dead some time I marry my secon' wife. Her name was Tempie Perkins. Later on, us sep'rate. Us sep'rate on 'count of money matters."

"I b'longs to de Baptis' Chu'ch. Sometime' de preacher come 'roun' and see me. He was here a few days ago dis week."[Pg 21]

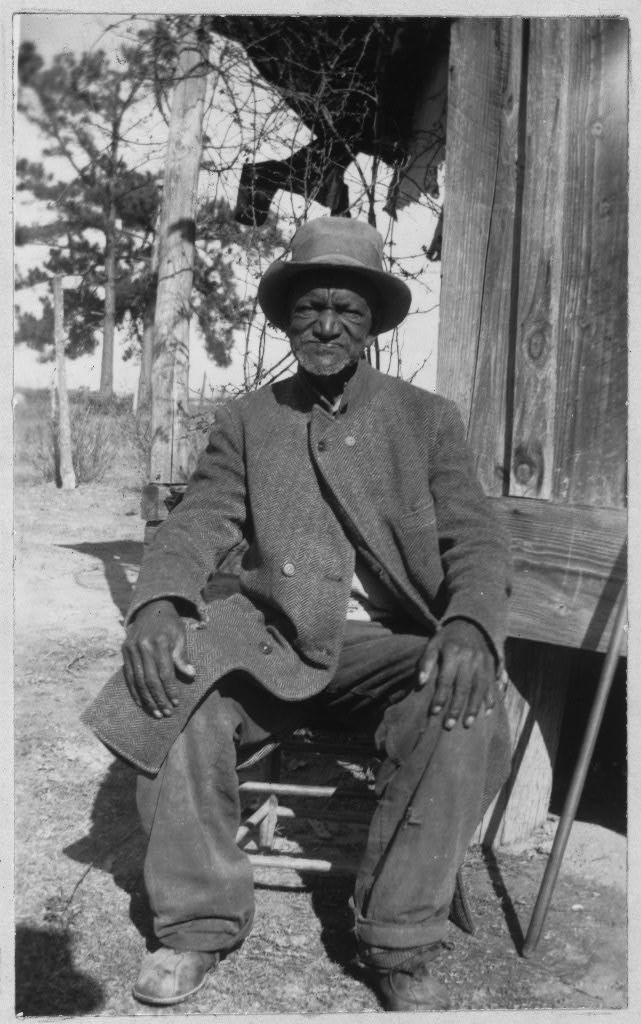

REFERENCES

A. Coronado's Children—J. Frank Dobie, Pub. 1929, Austin, Tex.

B. Leon County News—Centerville, Texas—Thursday May 21, 1936.

C. Consultant—Uncle Willis Anderson, resident of Centerville, Tex, born April 15, 1844.

An interesting character at Centerville, Texas, is "Uncle Willis" Anderson, an ex-slave, born April 15, 1844, 6 miles west of Centerville on the old McDaniels plantation near what is now known as Hopewell Settlement. It is generally said that "Uncle Willis" is one of the oldest living citizens in the County, black or white. He is referred to generally for information concerning days gone by and for the history of that County, especially in the immediate vicinity of Centerville.

"Uncle Willis" is an interesting figure. He may be found sitting on the porches of the stores facing Federal Highway No. 75, nodding or conversing with small groups of white or colored people that gather around him telling of the days gone by. He also likes to watch the busses and automobiles that pass through the small town musing and commenting on the swiftness of things today. Uncle Willis still cultivates a small patch five miles out from the town.

"Uncle Willis" is a tall dark, brown-skinned man having a large head covered with mixed gray wooly hair. He has lost very few teeth considering his age. When sitting on the porches of the stores the soles of his farm-shoes[Pg 22] may be seen tied together with pieces of wire. He supports himself with a cane made from the Elm tree. At present he wears a tall white Texas Centennial hat which makes him appear more unique than ever.

"Uncle Willis'" memory is vivid. He is familiar with the older figures in the history of the County. He tells tales of having travelled by oxen to West Texas for flour and being gone for six months at a time. He remembers the Keechi and the Kickapoo Indians and also claims that he can point out a tree where the Americans hung an Indian Chief. He says that he has plowed up arrows, pots and flints on the Reubens Bains place and on the McDaniel farms. He can tell of the early lawlessness in the County. His face lights up when he recalls how the Yankee soldiers came through Centerville telling the slave owners to free their slaves. He also talks very low when he mentions the name of Jeff Davis because he says, "Wha' man eavesdrops the niggers houses in slavery time and if yer' sed' that Jeff Davis was a good man, they barbecued a hog for you, but if yer' sed' that Abe Lincoln was a good man, yer' had to fight or go to the woods."

Among the most interesting tales told by "Uncle Willis" is the tale of the "Lead mine." "Uncle Willis" says that some where along Boggy Creek near a large hickory tree and a red oak tree, near Patrick's Lake, he and his master, Auss McDaniels, would dig lead out of the ground which they used to make pistol and rifle balls for the old Mississippi rifles during slavery time. Uncle Willis claims that they would dig slags of lead out of the ground some 12 and 15 inches long, and others as large as a man's fist. They would carry this ore back to the big house and melt it down to get the trash out of it, then they would pour it into molds and make rifle balls and pistol[Pg 23] balls from it. In this way they kept plenty of amunition on hand. In recent years the land has changed ownership, and the present owners live in Dallas. Learning of the tale of the "lead mine" on their property they went to Centerville in an attempt to locate it and were referred to "Uncle Willis." Uncle Willis says they offered him two hundred dollars if he could locate the mine. Being so sure that he knew its exact location, said that the $200 was his meat. However, Uncle Willis was unable to locate the spot where they dug the lead and the mine remains a mystery.[C]

Recently a group of citizens of Leon County including W.D. Lacey, Joe McDaniel, Debbs Brown, W.H. Hill and Judge Lacey cross questioned Uncle Willis about the lead mine. Judge Lacey did the questioning while them others formed an audience. The conversation went as follows:

"Which way would you go when you went to the mine?" Judge Lacey asked.

"Out tow'hd Normangee."

"How long would it take you to get there?"

"Two or three hours."

"Was it on a creek?"

"Yessuh."

"But you cant go to it now?"

"Nosuh, I just can't recollect exactly where 'tis.[B]

J. Frank Dobie mentions many tales of lost lead mines throughout Texas in Coronado's Children, a publication of the Texas Folk-Lore Society.[Pg 24] Lead in the early days of the Republic and the State was very valuable, as it was the source of protection from the Indians and also the means of supplying food.[A][Pg 25]

MARY ARMSTRONG, 91, lives at 3326 Pierce Ave., Houston, Texas. She was born on a farm near St. Louis, Missouri, a slave of William Cleveland. Her father, Sam Adams, belonged to a "nigger trader," who had a farm adjoining the Cleveland place.

"I's Aunt Mary, all right, but you all has to 'scuse me if I don't talk so good, 'cause I's been feelin' poorly for a spell and I ain't so young no more. Law me, when I think back what I used to do, and now it's all I can do to hobble 'round a little. Why, Miss Olivia, my mistress, used to put a glass plumb full of water on my head and then have me waltz 'round the room, and I'd dance so smoothlike, I don't spill nary drap.

"That was in St. Louis, where I's born. You see, my mamma belong to old William Cleveland and old Polly Cleveland, and they was the meanest two white folks what ever lived, 'cause they was allus beatin' on their slaves. I know, 'cause mamma told me, and I hears about it other places, and besides, old Polly, she was a Polly devil if there ever was one, and she whipped my little sister what was only nine months old and jes' a baby to death. She come and took the diaper offen my little sister and whipped till the blood jes' ran—jes' 'cause she cry like all babies do, and it kilt my sister. I never forgot that, but I sot some even with that old Polly devil and it's this-a-way.[Pg 26]

"You see, I's 'bout 10 year old and I belongs to Miss Olivia, what was that old Polly's daughter, and one day old Polly devil comes to where Miss Olivia lives after she marries, and trys to give me a lick out in the yard, and I picks up a rock 'bout as big as half your fist and hits her right in the eye and busted the eyeball, and tells her that's for whippin' my baby sister to death. You could hear her holler for five miles, but Miss Olivia, when I tells her, says, 'Well, I guess mamma has larnt her lesson at last.' But that old Polly was mean like her husban', old Cleveland, till she die, and I hopes they is burnin' in torment now.

"I don't 'member 'bout the start of things so much, 'cept what Miss Olivia and my mamma, her name was Siby, tells me. Course, it's powerful cold in winter times and the farms was lots different from down here. They calls 'em plantations down here but up at St. Louis they was jes' called farms, and that's what they was, 'cause we raises wheat and barley and rye and oats and corn and fruit.

"The houses was builded with brick and heavy wood, too, 'cause it's cold up there, and we has to wear the warm clothes and they's wove on the place, and we works at it in the evenin's.

"Old Cleveland takes a lot of his slaves what was in 'custom' and brings 'em to Texas to sell. You know, he wasn't sposed to do that, 'cause when you's in 'custom', that's 'cause he borrowed money on you, and you's not sposed to leave the place till he paid up. Course, old Cleveland jes' tells the one he owed the money to, you had run off, or squirmed out some way, he was that mean.[Pg 27]

"Mamma say she was in one bunch and me in 'nother. Mamma had been put 'fore this with my papa, Sam Adams, but that makes no diff'rence to Old Cleveland. He's so mean he never would sell the man and woman and chillen to the same one. He'd sell the man here and the woman there and if they's chillen, he'd sell them some place else. Oh, old Satan in torment couldn't be no meaner than what he and Old Polly was to they slaves. He'd chain a nigger up to whip 'em and rub salt and pepper on him, like he said, 'to season him up.' And when he'd sell a slave, he'd grease their mouth all up to make it look like they'd been fed good and was strong and healthy.

"Well mamma say they hadn't no more'n got to Shreveport 'fore some law man cotch old Cleveland and takes 'em all back to St. Louis. Then my little sister's born, the one old Polly devil kilt, and I's 'bout four year old then.

"Miss Olivia takes a likin' to me and, though her papa and mama so mean, she's kind to everyone, and they jes' love her. She marries to Mr. Will Adams what was a fine man, and has 'bout five farms and 500 slaves, and he buys me for her from old Cleveland and pays him $2,500.00, and gives him George Henry, a nigger, to boot. Lawsy, I's sho' happy to be with Miss Olivia and away from old Cleveland and Old Polly, 'cause they kilt my little sister.

"We lives in St. Louis, on Chinquapin Hill, and I's housegirl, and when the babies starts to come I nusses 'em and spins thread for clothes on the loom. I spins six cuts of thread a week, but I has plenty of time for myself and that's where I larns to dance so good. Law, I sho' jes' crazy 'bout dancin'. If I's settin' eatin' my victuals and hears a fiddle play, I gets up and dances.[Pg 28]

"Mr. Will and Miss Olivia sho' is good to me, and I never calls Mr. Will 'massa' neither, but when they's company I calls him Mr. Will and 'round the house by ourselves I calls them 'pappy' and 'mammy', 'cause they raises me up from the little girl. I hears old Cleveland done took my mamma to Texas 'gain but I couldn't do nothin', 'cause Miss Olivia wouldn't have much truck with her folks. Once in a while old Polly comes over, but Miss Olivia tells her not to touch me or the others. Old Polly trys to buy me back from Miss Olivia, and if they had they'd kilt me sho'. But Miss Olivia say, 'I'd wade in blood as deep as Hell 'fore I'd let you have Mary.' That's jes' the very words she told 'em.

"Then I hears my papa is sold some place I don't know where. 'Course, I didn't know him so well, jes' what mamma done told me, so that didn't worry me like mamma being took so far away.

"One day Mr. Will say, 'Mary, you want to go to the river and see the boat race?' Law me, I never won't forget that. Where we live it ain't far to the Miss'sippi River and pretty soon here they comes, the Natchez and the Eclipse, with smoke and fire jes' pourin' out of they smokestacks. That old captain on the 'Clipse starts puttin' in bacon meat in the boiler and the grease jes' comes out a-blazin' and it beat the Natchez to pieces.

"I stays with Miss Olivia till '63 when Mr. Will set us all free. I was 'bout 17 year old then or more. I say I goin' find my mamma. Mr. Will fixes me up two papers, one 'bout a yard long and the other some smaller, but both has big, gold seals what he says is the seal of the State of Missouri. He gives me money and buys my fare ticket to Texas and tells me they is still[Pg 29] slave times down here and to put the papers in my bosom but to do whatever the white folks tells me, even if they wants to sell me. But he say, 'Fore you gets off the block, jes' pull out the papers, but jes' hold 'em up to let folks see and don't let 'em out of your hands, and when they sees them they has to let you alone.'

"Miss Olivia cry and carry on and say be careful of myself 'cause it sho' rough in Texas. She give me a big basket what had so much to eat in it I couldn't hardly heft it and 'nother with clothes in it. They puts me in the back end a the boat where the big, old wheel what run the boat was and I goes to New Orleans, and the captain puts me on 'nother boat and I comes to Galveston, and that captain puts me on 'nother boat and I comes up this here Buffalo Bayou to Houston.

"I looks 'round Houston, but not long. It sho' was a dumpy little place then and I gets the stagecoach to Austin. It takes us two days to get there and I thinks my back busted sho' 'nough, it was sich rough ridin'. Then I has trouble sho'. A man asks me where I goin' and says to come 'long and he takes me to a Mr. Charley Crosby. They takes me to the block what they sells slaves on. I gets right up like they tells me, 'cause I 'lects what Mr. Will done told me to do, and they starts biddin' on me. And when they cried off and this Mr. Crosby comes up to get me, I jes' pulled out my papers and helt 'em up high and when he sees 'em, he say, 'Let me see them.' But I says, 'You jes' look at it up here,' and he squints up and say, 'This gal am free and has papers,' and tells me he a legislature man and takes me and lets me stay with his slaves. He is a good man.

"He tells me there's a slave refugee camp in Wharton County but I didn't have no money left, but he pays me some for workin' and when the war's over I starts to hunt mamma 'gain, and finds her in Wharton County near where Wharton is. Law me, talk 'bout cryin' and singin' and cryin' some more, we sure done it. I stays with mamma till I gets married in 1871 to John Armstrong,[Pg 30] and then we all comes to Houston.

"I gets me a job nussin' for Dr. Rellaford and was all through the yellow fever epidemic. I 'lects in '75 people die jes' like sheep with the rots. I's seen folks with the fever jump from their bed with death on 'em and grab other folks. The doctor saved lots of folks, white and black, 'cause he sweat it out of 'em. He mixed up hot water and vinegar and mustard and some else in it.

"But, law me, so much is gone out of my mind, 'cause I's 91 year old now and my mind jes' like my legs, jes' kinda hobble 'round a bit.[Pg 31]

STEARLIN ARNWINE, 94, was born a slave to Albertus Arnwine, near Jacksonville, Texas, who died when Stearlin was seven or eight. He was bought by John Moseley, of Rusk, Texas, who made Stearlin a houseboy, and was very kind to him. He now lives about six miles west of Jacksonville.

"I was bo'n 'fore de war, in 1853, right near this here town, on Gum Creek. My mammy belonged to Massa Albertus Arnwine, and he wasn' ever married. He owned four women, my mammy, Ann, my grandmother, Gracie, and my Aunt Winnie and Aunt Mary. He didn' own any nigger men, 'cept the chillen of these women. Grandma lived in de house with Massa Arnwine and the rest of us lived in cabins in de ya'd. My mammy come from Memphis but I don' know whar my pappy come from. He was Ike Lane. I has three half brothers, and their names is Joe and Will and John Schot, and two sisters called Polly and Rosie.

"Massa Arnwine died 'fore de war and he made a will and it gave all he owned to the women he owned, and Jedge Jowell promised massa on his deathbed he would take us to de free country, but he didn'. He took us to his place to work for him for 'bout two years and the women never did get that 900 acres of land Massa Arnwine willed to'em. I don' know who got it, but they didn'. I knows I still has a share in that land, but it takes money to git it in cou't.

"When war broke I fell into the han's of Massa John Moseley at Rusk. They brought the dogs to roun' us up from the fiel's whar we was workin'. I was the only one of my fam'ly to go to Massa John.[Pg 32]

"I never did wo'k in the fiel's at Massa John's place. He said I mus' be his houseboy and houseboy I was. Massa was sho' good to me and I did love to be with him and follow him 'roun'.

"The kitchen was out in de ya'd and I had to carry the victuals to the big dinin'-room. When dinner was over, Massa John tuk a nap and I had to fan him, and Lawsy me, I'd git so sleepy. I kin hear him now, for he'd wake up and say, 'Go get me a drink outta the northeast corner of de well.'

"We had straw and grass beds, we put it in sacks on de groun' and slep' on de sacks. I don' 'member how much land Massa John had but it was a big place and he had lots of slaves. We chillun had supper early in de evenin' and mostly cornbread and hawg meat and milk. We all ate from a big pot. I larned to spin and weave and knit and made lots of socks.

"Massa John had two step-daughters, Miss Mollie and Miss Laura, and they wen' to school at Rusk. It was my job to take 'em thar ev'ry Monday mornin' on horses and go back after 'em Friday afternoon.

"I never earnt no money 'fore freedom come, but once my brother-in-law give me five dollars. I was so proud of it I showed it to de ladies and one of 'em said, 'You don' need dat,' and she give me two sticks of candy and tuk de money. But I didn' know any better then.

"I seed slaves for sale on de auction block. They sol' 'em 'cordin' to strengt' and muscles. They was stripped to de wais'. I seed the women and little chillun cryin' and beggin' not to be separated, but it didn' do no good. They had to go.[Pg 33]

"The only chu'ch I knowed 'bout was when we'd git together in de night and have prayer meetin' and singin.' We use' to go way out in de woods so de white folks wouldn' hear nothin'. Sometimes we'd stay nearly all night on Saturday, 'cause we didn' have to work Sunday.

"'Bout the only thing we could play was stick hosses. I made miles and miles on the stick hosses. After the War Massa John have his chillun a big roll of Confederate money and they give us some of it to trade and buy stick hosses with.

"When Massa John tol' us we was free, he didn' seem to min', but Miss Em, she bawled and squalled, say her prop'ty taken 'way from her. After dat, my mammy gathers us togedder and tuk us to the Dr. Middleton place, out from Jacksonville. From thar to de Ragsdale place whar I's been ever since.

"I wore my first pants when I was fourteen years ole, and they stung 'till I was mis'ble. The cloth was store bought but mammy made the pants at home. It was what we called dog-hair cloth. Mammy made my first shoes, we called 'em 'red rippers'.[Pg 34]

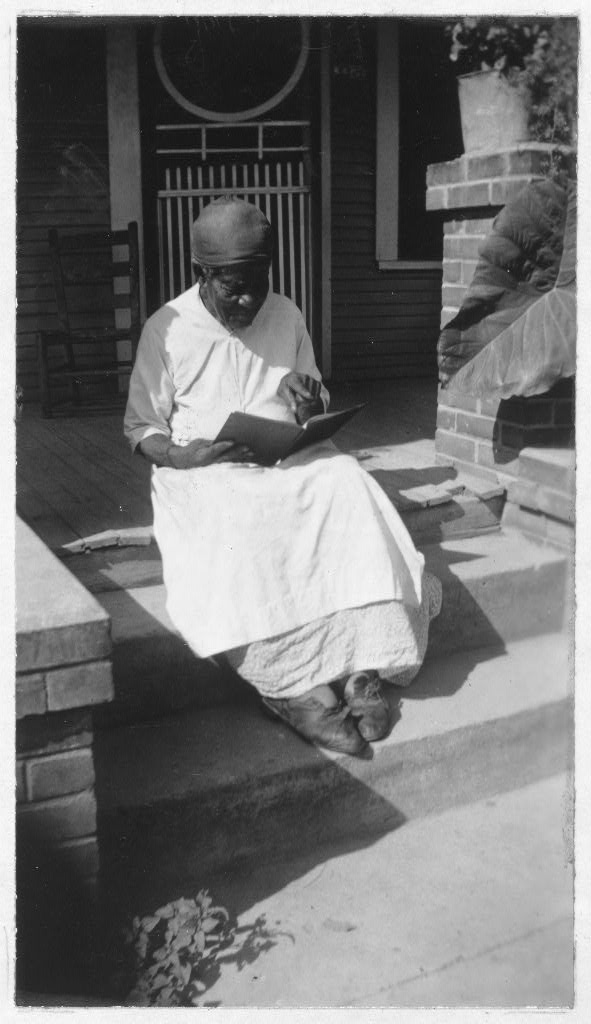

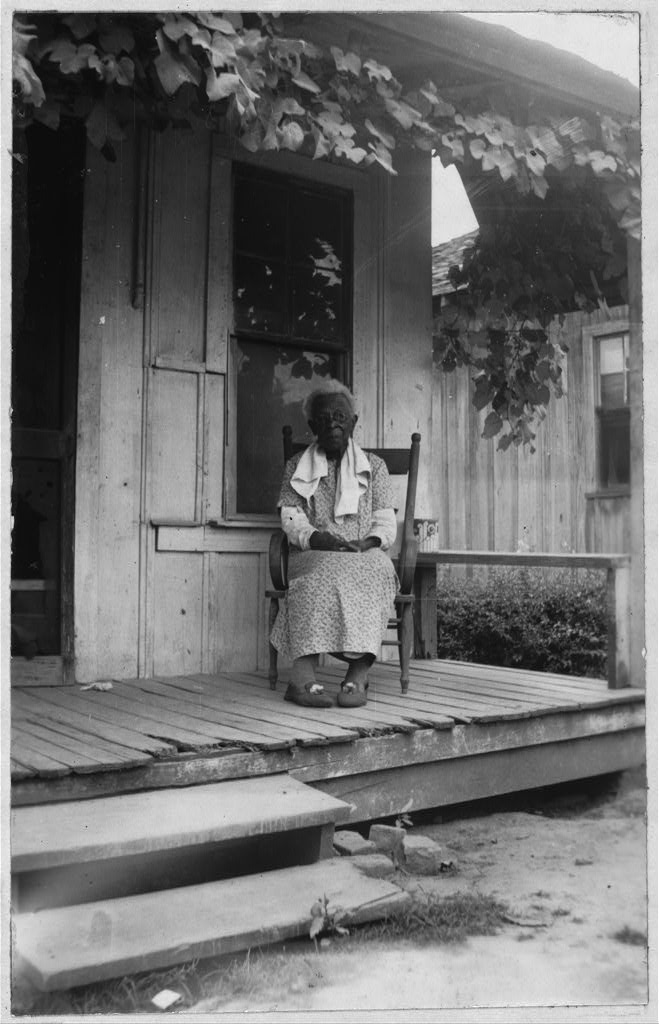

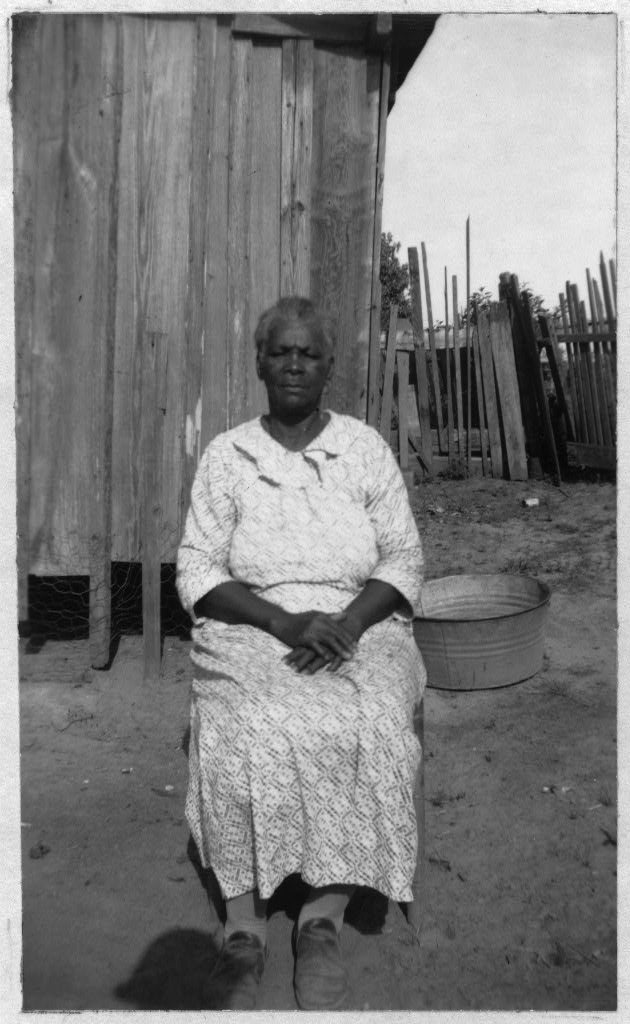

SARAH ASHLEY, 93, was born in Mississippi. She recalls her experiences when sold on the block in New Orleans, and on a cotton plantation in Texas. She now lives at Goodrich, Texas.

"I ain't able to do nothin' no more. I's jus' plumb give out and I stays here by myself. My daughter, Georgia Grime, she used to live with me but she's been dead four year.

"I was born in Miss'ippi and Massa Henry Thomas buy us and bring us here. He a spec'lator and buys up lots of niggers and sells 'em. Us family was sep'rated. My two sisters and my papa was sold to a man in Georgia. Den dey put me on a block and bid me off. Dat in New Orleans and I scairt and cry, but dey put me up dere anyway. First dey takes me to Georgia and dey didn't sell me for a long spell. Massa Thomas he travel round and buy and sell niggers. Us stay in de spec'lators drove de long time.

"After 'while Massa Mose Davis come from Cold Spring, in Texas, and buys us. He was buyin' up little chillen for he chillen. Dat 'bout four year befo' da first war. I was 19 year old when de burst of freedom come in June and I git turn loose.

"I was workin' in de field den. Jus' befo' dat de old Massa he go off and buy more niggers. He go east. He on a boat what git stove up and he die and never come back no more. Us never see him no more.[Pg 35]

"I used to have to pick cotton and sometime I pick 300 pound and tote it a mile to de cotton house. Some pick 300 to 800 pound cotton and have to tote de bag de whole mile to de gin. Iffen dey didn't do dey work dey git whip till dey have blister on 'em. Den iffen dey didn't do it, de man on a hoss goes down de rows and whip with a paddle make with holes in it and bus' de blisters. I never git whip, 'cause I allus git my 300 pound. Us have to go early to do dat, when de horn goes early, befo' daylight. Us have to take de victuals in de bucket to de field.

"Massa have de log house and us live in little houses, strowed in long rows. Dere wasn't no meetin's 'lowed in de quarters and iffen dey have prayer meetin' de boss man whip dem. Sometime us run off at night and go to camp meetin'. I takes de white chillen to church sometime, but dey couldn't larn me to sing no songs 'cause I didn' have no spirit.

"Us never got 'nough to eat, so us keeps stealin' stuff. Us has to. Dey give us de peck of meal to last de week and two, three pound bacon in chunk. Us never have flour or sugar, jus' cornmeal and de meat and 'taters. De niggers has de big box under de fireplace, where dey kep' all de pig and chickens what dey steal, down in salt.

"I seed a man run away and de white men got de dogs and dey kotch him and put him in de front room and he jump through de big window and break de glass all up. Dey sho' whips him when dey kotches him.

"De way dey whip de niggers was to strip 'em off naked and whip 'em till dey make blisters and bus' de blisters. Den dey take de salt[Pg 36] and red pepper and put in de wounds. After dey wash and grease dem and put somethin' on dem, to keep dem from bleed to death.

"When de boss man told us freedom was come he didn't like it, but he give all us de bale of cotton and some corn. He ask us to stay and he'p with de crop but we'uns so glad to git 'way dat nobody stays. I got 'bout fifty dollars for de cotton and den I lends it to a nigger what never pays me back yit. Den I got no place to go, so I cooks for a white man name' Dick Cole. He sposen give me $5.00 de month but he never paid me no money. He'd give me eats and clothes, 'cause he has de little store.

"Now, I's all alone and thinks of dem old times what was so bad, and I's ready for de Lawd to call me."[Pg 37]

AGATHA BABINO, born a slave of Ogis Guidry, near Carenco, Louisiana, now lives in a cottage on the property of the Blessed Sacrament Church, in Beaumont, Texas. She says she is at least eighty-seven and probably much older.

"Old Marse was Ogis Guidry. Old Miss was Laurentine. Dey had four chillen, Placid, Alphonse and Mary and Alexandrine, and live in a big, one-story house with a gallery and brick pillars. Dey had a big place. I 'spect a mile 'cross it, and fifty slaves.

"My mama name was Clarice Richard. She come from South Carolina. Papa was Dick Richard. He come from North Carolina. He was slave of old Placid Guilbeau. He live near Old Marse. My brothers was Joe and Nicholas and Oui and Albert and Maurice, and sisters was Maud and Celestine and Pauline.

"Us slaves lived in shabby houses. Dey builded of logs and have dirt floor. We have a four foot bench. We pull it to a table and set on it. De bed a platform with planks and moss.

"We had Sunday off. Christmas was off, too. Dey give us chicken and flour den. But most holidays de white folks has company. Dat mean more work for us.

"Old Marse bad. He beat us till we bleed. He rub salt and pepper in. One time I sweep de yard. Young miss come home from college. She slap my face. She want to beat me. Mama say to beat her, so dey did. She took de beatin' for me.

"My aunt run off 'cause dey beat her so much. Dey brung her back and beat her some more.[Pg 38]

"We have dance outdoors sometime. Somebody play fiddle and banjo. We dance de reel and quadrille and buck dance. De men dance dat. If we go to dance on 'nother plantation we have to have pass. De patterrollers come and make us show de slip. If dey ain't no slip, we git beat.

"I see plenty sojers. Dey fight at Pines and we hear ball go 'zing—zing.' Young marse have blue coat. He put it on and climb a tree to see. De sojers come and think he a Yankee. Dey take his gun. Dey turn him loose when dey find out he ain't no Yankee.

"When de real Yankees come dey take corn and gooses and hosses. Dey don't ask for nothin'. Dey take what dey wants.

"Some masters have chillen by slaves. Some sold dere own chillen. Some sot dem free.

"When freedom come we have to sign up to work for money for a year. We couldn't go work for nobody else. After de year some stays, but not long.

"De Ku Klux kill niggers. Dey come to take my uncle. He open de door. Dey don't take him but tell him to vote Democrat next day or dey will. Dey kilt some niggers what wouldn't vote Democrat.

"Dey kill my old uncle Davis. He won't vote Democrat. Dey shoot him. Den dey stand him up and let him fall down. Dey tie him by de feet. Dey drag him through de bresh. Dey dare his wife to cry.

"When I thirty I marry Tesisfor Babino. Pere Abadie marry us at Grand Coteau. We have dinner with wine. Den come big dance. We have twelve chillen. We works in de field in Opelousas. We come here twenty-five year ago. He die in 1917. Dey let's me live here. It nice to be near de church. I can go to prayers when I wants to.[Pg 39]

MRS. JOHN BARCLAY (nee Sarah Sanders) Brownwood, Texas was born in Komo, Mississippi, September 1, 1853. She was born a slave at the North Slades' place. Mr. and Mrs. North Slade were the only owners she ever had. She served as nurse-maid for her marster's children and did general housework. She, with her mother and father and family stayed with the Slades until the end of the year after the Civil War. They then moved to themselves, hiring out to "White Folks."

"My marster and mistress was good to all de slaves dat worked for dem. But our over-seer, Jimmy Shearer, was sho' mean. One day he done git mad at me for some little somethin' and when I take de ashes to de garden he catches me and churns me up and down on de groun'. One day he got mad[Pg 40] at my brother and kicked him end over end, jes' like a stick of wood. He would whip us 'til we was raw and then put pepper and salt in de sores. If he thought we was too slow in doin' anything he would kick us off de groun' and churn us up and down. Our punishment depended on de mood of de over-seer. I never did see no slaves sold. When we was sick dey give us medicine out of drug stores. De over-seer would git some coarse cotton cloth to make our work clothes out of and den he would make dem so narrow we couldn' hardly' walk.

"There was 1800 acres in Marster Slade's plantation, we got up at 5:00 o'clock in de mornin' and de field workers would quit after sun-down. We didn' have no jails for slaves. We went to church with de white folks and there was a place in de back of de church for us to sit.

"I was jes' a child den and us chilluns would gather in de back yard and sing songs and play games and dance jigs. Song I 'member most is 'The Day is Past and Gone.'

"One time marster found out the over-seer was so mean to me, so he discharged him and released me from duty for awhile.

"We never did wear shoes through de week but on Sunday we would dress up in our white cotton dresses and put on shoes.

"We wasn't taught to read or write. Our owner didn't think anything about it. We had to work if there was work to be done. When we got caught up den we could have time off. If any of us got sick our mistress would 'tend to us herself. If she thought we was sick enough she would call de white doctor.

"When de marster done told us we was free we jumped up and[Pg 41] down and slapped our hands and shouted 'Glory to God!' Lord, child dat was one happy bunch of niggers. Awhile after dat some of de slaves told marster dey wanted to stay on with him like dey had been but he told 'em no dey couldn't, 'cause dey was free. He said he could use some of 'em but dey would have to buy what dey got and he would have to pay 'em like men.

"When I was 'bout 18 years old I married John Barclay. I's had ten chillun and four gran'-chillun and now I lives by myself."[Pg 42]

JOHN BARKER, age 84, Houston.

5 photographs marked Green Cumby have been assigned to this manuscript—the 'Green Cumby' photos are attached to the proper manuscript and the five referred to above are probably pictures of John Barker.

JOHN BARKER, age 84, was born near Cincinnati, Ohio, the property of the Barker family, who moved to Missouri and later to Texas. He and his wife live in a neat cottage in Houston, Texas.

"I was born a slave. I'm a Malagasser (Madagascar) nigger. I 'member all 'bout dem times, even up in Ohio, though de Barkers brought me to Texas later on. My mother and father was call Goodman, but dey died when I was little and Missy Barker raised me on de plantation down near Houston. Dey was plenty of work and plenty of room.

"I 'member my grandma and grandpa. In dem days de horned toads runs over de world and my grandpa would gather 'em and lay 'em in de fireplace till dey dried and roll 'em with bottles till dey like ashes and den rub it on de shoe bottoms. You see, when dey wants to run away, dat stuff don't stick all on de shoes, it stick to de track. Den dey carries some of dat powder and throws it as far as dey could jump and den jump over it, and do dat again till dey use all de powder. Dat throwed de common hounds off de trail altogether. But dey have de bloodhounds, hell hounds, we calls 'em, and dey could pick up dat trail. Dey run my grandpa over 100 mile and three or four days and nights and found him under a bridge. What dey put on him was enough! I seen 'em whip runaway niggers till de blood run down dere backs and den put salt in de places.

"I 'spect dere was 'bout 40 or 50 acres in de plantation. Dey worked and worked and didn't have no dances or church. Dances nothin![Pg 44]

"My massa and missus house was nice, but it was a log house. They had big fireplaces what took great big chunks of wood and kep' fire all night. We lives in de back in a little bitty house like a chicken house. We makes beds out of posts and slats across 'em and fills tow sacks with shucks in 'em for mattress and pillows.

"I seed slaves sold and they was yoked like steers and sold by pairs sometimes. Dey wasn't 'lowed to marry, 'cause they could be sold and it wasn't no use, but you could live with 'em.

"We used to eat possums and dese old-fashioned coons and ducks. Sometimes we'd eat goats, too. We has plenty cornmeal and 'lasses and we gets milk sometimes, but we has no fine food, 'cept on Christmas, we gits some cake, maybe.

"My grandma says one day dat we all is free, but we stayed with Massa Barker quite a while. Dey pays us for workin' but it ain't much pay, 'cause de war done took dere money and all. But they was good to us, so we stayed.

"I was 'bout 20 when I marries de fust time. It was a big blow-out and I was scared de whole time. First time I ever tackled marryin'. Dey had a big paper sack of rice and throwed it all over her and I, enough rice to last three or four days, throwed away jus' for nothin'. I had on a black, alpaca suit with frock tail coat and, if I ain't mistaken, a right white shirt. My wife have a great train on her dress and one dem things you call a wreath. I wore de loudest shoes we could find, what you call patent leather.

"Dis here my third wife. We marries in Eagle Pass and comes up to de Seminole Reservation and works for de army till we goes to work for[Pg 45] de Pattersons, and we been here 23 years now.

"Ghosties? I was takin' care of a white man when he died and I seed something 'bout three feet high and black. I reckon I must have fainted 'cause they has de doctor for me. And on dark nights I seed ghosties what has no head. Dey looks like dey wild and dey is all in different performance. When I goin' down de road and feel a hot steam and look over my shoulder I can see 'em plain as you standin' dere. I seed 'em when my wife was with me, but she can't see 'em, 'cause some people ain't gifted to see 'em.[Pg 46]

JOE BARNES, 89, was born in Tyler Co., Texas, on Jim Sapp's plantation. He is very feeble, but keeps his great grandchildren in line while their mother works. They live in Beaumont. Joe is tall, slight, and has gray hair and a stubby gray mustache. In his kind, gentle voice he relates his experiences in slavery days.

"Dey calls me Paul Barnes, but my name ain't Paul, it am Joe. My massa was Jim Sapp, up here in Tyler County, and missus' name was Ann. De Sapp place was big and dey raise' a sight of cotton and corn. Old massa Jim he have 'bout 25 or 30 slaves.

"My mammy's name was Artimisi, but dey call her Emily, and pa's name Jerry Wooten, 'cause he live on de Wooten place. My steppa named Barnes and I taken dat name. My parents, dey have de broomstick weddin'.

"When I's a chile us play marbles and run rabbits and ride de stick hoss and de like. When I gits more bigger, us play ball, sort of like baseball. One time my brudder go git de hosses and dey lots of rain and de creek swoll up high. De water so fast it wash him off he hoss and I ain't seed him since. Dey never find de body. He's 'bout ten year old den.

"Massa live in de big box house and de quarters am in a row in de back. Some of dem box and some of dem log. Dey have two rooms. Every day de big, old cowhorn blow for dinner and us have de little tin cup what us git potlicker in and meat and cornbread and salt bacon. Us gits greens, too. De chimneys 'bout four feet wide and dey cooks everything in de fireplace. Dey have pots and ovens and put fire below and 'bove 'em.[Pg 47]

"I used to wear what I calls a one-button cutaway. It was jis' a shirt make out of homespun with pleats down front. Dey make dey own cloth dem time.

"Massa marry de folks in de broomstick style. Us don' have de party but sometime us sing and play games, like de round dance.

"Dey give de little ones bacon to suck and tie de string to de bacon and de other round dey wrists, so dey won't swallow or lose de bacon. For de little bits of ones dey rings de bell for dey mommers to come from de field and nuss 'em.

"After freedom come us stay a year and den move to Beaumont and us work in de sawmill for Mr. Jim Long. De fust money I git I give to my mammy. Me and mammy and stepdaddy stays in Beaumont two years den moves to Tyler and plants de crop. But de next year us move back to Beaumont on de Langham place and mammy work for de Longs till she die.

"When I git marry I marry Dicey Allen and she die and I never marry no more. I worked in sawmillin' and on de log pond and allus gits by pretty good. I ain't done no work much de last ten year, I's too old.

"I sort a looks after my grandchillen and I sho' loves dem. I sits 'round and hurts all de time. It am rheumatism in de feets, I reckon. I got six grandchillen and three great-grandchillen and dat one you hears cryin', dat de baby I's raisin' in dere.

"I's feared I didn't tell you so much 'bout things way back, but da truth am, I can't 'member like I used to.[Pg 48]

ARMSTEAD BARRETT, born in 1847, was a slave of Stafford Barrett, who lived in Huntsville, Texas. He is the husband of Harriett Barrett. Armstead has a very poor memory and can tell little about early days. He and Harriet receive old age pensions.

"I's really owned by Massa Stafford Barrett, but my mammy 'longed to Massa Ben Walker and was 'lowed to keep me with her. So after we'uns got free, I lives with my daddy and mammy and goes by de name of Barrett. Daddy's name was Henry Barrett and he's brung to Texas from Richmond, in Virginny, and mammy come from Kentucky. Us all lived in Huntsville. I waited on Miss Ann and mammy was cook.

"Old massa have doctor for us when us sick. We's too val'ble. Jus' like to de fat beef, massa am good to us. Massa go to other states and git men and women and chile slaves and bring dem back to sell, 'cause he spec'lator. He make dem wash up good and den sell dem.

"Mos' time we'uns went naked. Jus' have on one shirt or no shirt a-tall.

"I know when peace 'clared dey all shoutin'. One woman hollerin' and a white man with de high-steppin' hoss ride clost to her and I see him git out and open he knife and cut her wide 'cross de stomach. Den he put he hat inside he shirt and rid off like lightnin'. De woman put in wagon and I never heered no more 'bout her.

"I didn't git nothin' when us freed. Only some cast-off clothes. Long time after I rents de place on halves and farms most my life. Now I's too old to work and gits a pension to live on.[Pg 49]

"I seems to think us have more freedom when us slaves, 'cause we have no 'sponsibility for sickness den. We have to take care all dat now and de white man, he beats de nigger out what he makes. Back in de old days, de white men am hones'. All the nigger knowed was hard work. I think de cullud folks ought to be 'lowed more privileges in votin' now, 'cause dey have de same 'sponsibility as white men and day more and more educated and brighter and brighter.

"I think our young folks pretty sorry. They wont do right, but I 'lieve iffen dey could git fair wages dey'd do better. Dey git beat out of what dey does, anyway.

"I 'member a owner had some slaves and de overseer had it in for two of dem. He'd whip dem near every day and dey does all could be did to please him. So one day he come to de field and calls one dem slaves and dat slave draps he hoe and goes over and grabs dat overseer. Den de other slave cut dat overseer's head right slap off and throwed it down one of de rows. De owner he fools 'round and sells dem two slaves for $800.00 each and dat all de punishment dem two slaves ever got.[Pg 50]

HARRIET BARRETT, 86, was born in Walker Co., Texas, in 1851, a slave of Steve Glass. She now lives in Palestine, Texas.

"Massa Steve Glass, he own my pappy and mammy and me, until the war freed us. Pappy's borned in Africy and mammy in Virginy, and brung to Texas 'fore de war, and I's borned in Texas in 1851. I's heered my grandpa was wild and dey didn't know 'bout marryin' in Africy. My brother name Steve Glass and I dunno iffen I had sisters or not.

"Dey put me to cookin' when I's a li'l kid and people says now dat Aunt Harriet am de bes' cook in Madisonville. Massa have great big garden and plenty to eat. I's cook big skillet plumb full corn at de time and us all have plenty meat. Massa, he step out and kill big deer and put in de great big pot and cook it. Then us have cornbread and syrup.

"Us have log quarters with stick posts for bed and deerskin stretch over it. Den us pull moss and throw over dat. I have de good massa, bless he soul. Missy, she plumb good. She sick all de time and dey never have white chillen. Dey live in big, log house, four rooms in it and de great hall both ways through it.

"Massa, he have big bunch slaves and work dem long as dey could see and den lock 'em up in de quarters at night to keep 'em from runnin' off. De patterrollers come and go through de quarters to see if all de niggers dere. Dey walk right over us when us sleeps.

"Some slave run off, gwine to de north, and massa he cotch him and give him thirty-nine licks with rawhide and lock dem up at night, too, and keep chain on him in daytime.[Pg 51]

"I have de good massa, bless he soul, and missy she plumb good. I'll never forgit dem. Massa 'low us have holiday Saturday night and go to nigger dance if it on 'nother plantation. Boy, oh boy, de tin pan beatin' and de banjo pickin' and de dance all night long.

"When de war start, white missy die, and massa have de preacher. She was white angel. Den massa marry Missy Alice Long and she de bad woman with us niggers. She hard on us, not like old missy.

"I larned lots of remedies for sick people. Charcoal and onions and honey for de li'l baby am good, and camphor for de chills and fever and teeth cuttin'. I's boil red oak bark and make tea for fever and make cactus weed root tea for fever and chills and colic. De best remedy for chills and fever am to git rabbit foot tie on string 'round de neck.

"Massa, he carry me to war with him, 'cause I's de good cook. In dat New Orleans battle he wounded and guns roarin' everywhere. Dey brung massa in and I's jus' as white as he am den. Dem Yankees done shoot de roof off de house. I nuss de sick and wounded clean through de war and seed dem dyin' on every side of me.

"I's most scared to death when de war end. Us still in New Orleans and all de shoutin' dat took place 'cause us free! Dey crowds on de streets and was in a stir jus' as thick as flies on de dog. Massa say I's free as him, but iffen I wants to cook for him and missy I gits $2.50 de month, so I cooks for him till I marries Armstead Barrett, and then us farm for de livin'. Us have big church weddin' and I has white loyal dress and black brogan shoes. Us been married 51 years now.[Pg 52]

JOHN BATES, 84, was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, a slave of Mock Bateman. When still very young, John moved with his mother, a slave of Harry Hogan, to Limestone Co., Texas. John now lives in Corsicana, supported by his children and an old age pension.

"My pappy was Ike Bateman, 'cause his massa's name am Mock Bateman, and mammy's name was Francis. They come from Tennessee and I had four brothers and six sisters. We jes' left de last part of de name off and call it Bates and dat's how I got my name. Mammy 'longed to Massa Harry Hogan and while I's small us move to Texas, to Limestone County, and I don't 'member much 'bout pappy, 'cause I ain't never seed him since.

"Massa Hogan was a purty good sort of fellow, but us went hongry de fust winter in Texas. He lived in de big log house with de hallway clean through and a gallery clean 'cross de front. De chimney was big 'nough to burn logs in and it sho' throwed out de heat. It was a good, big place and young massa come out early and holler for us to git up and be in de field.

"Missy Hogan was de good woman and try her dead level best to teach me to read and write, but my head jes' too thick, I jes' couldn't larn. My Uncle Ben he could read de Bible and he allus tell us some day us be free and Massa Harry laugh, haw, haw, haw, and he say, 'Hell, no, yous never be free, yous ain't got sense 'nough to make de livin' if yous was free.' Den he takes de Bible 'way from Uncle Ben and say it put de bad ideas in he head, but Uncle gits 'nother Bible and hides it and massa never finds it out.[Pg 53]

"We'uns goes to de big baptisin' one time and it's at de big sawmill tank and 50 is baptise' and I's in dat bunch myself. But dey didn't have no funerals for de slaves, but jes' bury dem like a cow or a hoss, jes' dig de hole and roll 'em in it and cover 'em up.

"War come and durin' dem times jes' like today nearly everybody knows what gwine on, news travels purty fast, and iffen de slaves couldn't git it with de pass dey slips out after dark and go in another plantation by de back way. Course, iffen dem patterrollers cotch dem it jus' too bad and dey gits whip.