The Project Gutenberg EBook of Wilhelm Tell, by Friedrich Schiller

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Wilhelm Tell

A Play

Author: Friedrich Schiller

Release Date: October 26, 2006 [EBook #6788]

Last Updated: July 20, 2014

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WILHELM TELL ***

Produced by Tapio Riikonen and David Widger

HERMANN GESSLER, Governor of Schwytz and Uri. WERNER, Baron of Attinghausen, free noble of Switzerland. ULRICH VON RUDENZ, his Nephew. WERNER STAUFFACHER, | CONRAD HUNN, | HANS AUF DER MAUER, | JORG IM HOFE, | People of Schwytz. ULRICH DER SCHMIDT, | JOST VON WEILER, | ITEL REDING, | WALTER FURST, | WILHELM TELL, | ROSSELMANN, the Priest, | PETERMANN, Sacristan, | People of Uri. KUONI, Herdsman, | WERNI, Huntsman, | RUODI, Fisherman, | ARNOLD OF MELCHTHAL, | CONRAD BAUMGARTEN, | MEYER VON SARNEN, | STRUTH VON WINKELRIED, | People of Unterwald. KLAUS VON DER FLUE, | BURKHART AM BUHEL, | ARNOLD VON SEWA, | PFEIFFER OF LUCERNE. KUNZ OF GERSAU. JENNI, Fisherman's Son. SEPPI, Herdsman's Son. GERTRUDE, Stauffacher's Wife. HEDWIG, Wife of Tell, daughter of Furst. BERTHA OF BRUNECK, a rich heiress. ARMGART, | MECHTHILD, | Peasant women. ELSBETH, | HILDEGARD, | WALTER, | Tell's sons. WILHELM, | FRIESSHARDT, | Soldiers. LEUTHOLD, | RUDOLPH DER HARRAS, Gessler's master of the horse. JOHANNES PARRICIDA, Duke of Suabia. STUSSI, Overseer. THE MAYOR OF URI. A COURIER. MASTER STONEMASON, COMPANIONS, AND WORKMEN. TASKMASTER. A CRIER. MONKS OF THE ORDER OF CHARITY. HORSEMEN OF GESSLER AND LANDENBERG. MANY PEASANTS; MEN AND WOMEN FROM THE WALDSTETTEN.

A high, rocky shore of the lake of Lucerne opposite Schwytz.

The lake makes a bend into the land; a hut stands at a short

distance from the shore; the fisher boy is rowing about in his

boat. Beyond the lake are seen the green meadows, the hamlets,

and arms of Schwytz, lying in the clear sunshine. On the left

are observed the peaks of the Hacken, surrounded with clouds; to

the right, and in the remote distance, appear the Glaciers. The

Ranz des Vaches, and the tinkling of cattle-bells, continue for

some time after the rising of the curtain.

FISHER BOY (sings in his boat).

Melody of the Ranz des Vaches.

The clear, smiling lake wooed to bathe in its deep,

A boy on its green shore had laid him to sleep;

Then heard he a melody

Flowing and soft,

And sweet, as when angels

Are singing aloft.

And as thrilling with pleasure he wakes from his rest,

The waters are murmuring over his breast;

And a voice from the deep cries,

"With me thou must go,

I charm the young shepherd,

I lure him below."

HERDSMAN (on the mountains).

Air.—Variation of the Ranz des Vaches.

Farewell, ye green meadows,

Farewell, sunny shore,

The herdsman must leave you,

The summer is o'er.

We go to the hills, but you'll see us again,

When the cuckoo is calling, and wood-notes are gay,

When flowerets are blooming in dingle and plain,

And the brooks sparkle up in the sunshine of May.

Farewell, ye green meadows,

Farewell, sunny shore,

The herdsman must leave you,

The summer is o'er.

CHAMOIS HUNTER (appearing on the top of a cliff).

Second Variation of the Ranz des Vaches.

On the heights peals the thunder, and trembles the bridge,

The huntsman bounds on by the dizzying ridge,

Undaunted he hies him

O'er ice-covered wild,

Where leaf never budded,

Nor spring ever smiled;

And beneath him an ocean of mist, where his eye

No longer the dwellings of man can espy;

Through the parting clouds only

The earth can be seen,

Far down 'neath the vapor

The meadows of green.

[A change comes over the landscape. A rumbling, cracking

noise is heard among the mountains. Shadows of clouds sweep

across the scene.

[RUODI, the fisherman, comes out of his cottage. WERNI, the

huntsman, descends from the rocks. KUONI, the shepherd, enters,

with a milk pail on his shoulders, followed by SERPI, his assistant.

RUODI.

Bestir thee, Jenni, haul the boat on shore.

The grizzly Vale-king 1 comes, the glaciers moan,

The lofty Mytenstein 2 draws on his hood,

And from the Stormcleft chilly blows the wind;

The storm will burst before we are prepared.

KUONI.

'Twill rain ere long; my sheep browse eagerly,

And Watcher there is scraping up the earth.

WERNI.

The fish are leaping, and the water-hen

Dives up and down. A storm is coming on.

KUONI (to his boy).

Look, Seppi, if the cattle are not straying.

SEPPI. There goes brown Liesel, I can hear her bells.

KUONI.

Then all are safe; she ever ranges farthest.

RUODI.

You've a fine yoke of bells there, master herdsman.

WERNI.

And likely cattle, too. Are they your own?

KUONI.

I'm not so rich. They are the noble lord's

Of Attinghaus, and trusted to my care.

RUODI.

How gracefully yon heifer bears her ribbon!

KUONI.

Ay, well she knows she's leader of the herd,

And, take it from her, she'd refuse to feed.

RUODI.

You're joking now. A beast devoid of reason.

WERNI.

That's easy said. But beasts have reason too—

And that we know, we men that hunt the chamois.

They never turn to feed—sagacious creatures!

Till they have placed a sentinel ahead,

Who pricks his ears whenever we approach,

And gives alarm with clear and piercing pipe.

RUODI (to the shepherd).

Are you for home?

KUONI.

The Alp is grazed quite bare.

WERNI.

A safe return, my friend!

KUONI.

The same to you?

Men come not always back from tracks like yours.

RUODI.

But who comes here, running at topmost speed?

WERNI.

I know the man; 'tis Baumgart of Alzellen.

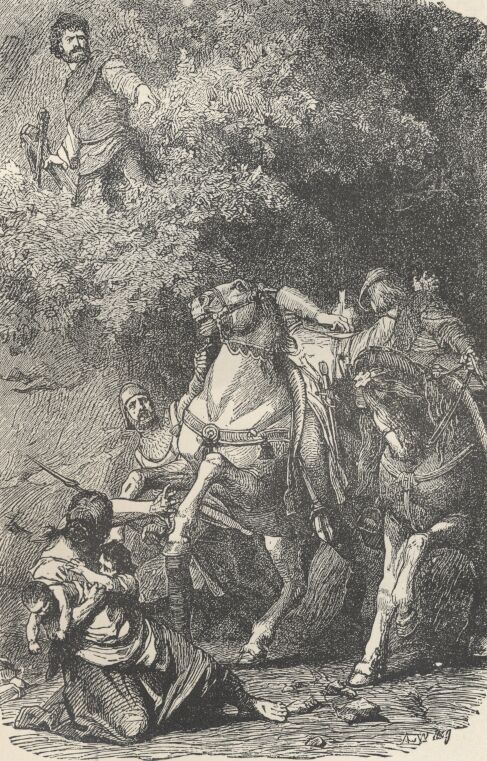

CONRAD BAUMGARTEN (rushing in breathless).

For God's sake, ferryman, your boat!

RUODI.

How now?

Why all this haste?

BAUMGARTEN.

Cast off! My life's at stake!

Set me across!

KUONI.

Why, what's the matter, friend?

WERNI.

Who are pursuing you? First tell us that.

BAUMGARTEN (to the fisherman).

Quick, quick, even now they're close upon my heels!

The viceroy's horsemen are in hot pursuit!

I'm a lost man should they lay hands upon me.

RUODI.

Why are the troopers in pursuit of you?

BAUMGARTEN.

First save my life and then I'll tell you all.

WERNI.

There's blood upon your garments—how is this?

BAUMGARTEN.

The imperial seneschal, who dwelt at Rossberg.

KUONI.

How! What! The Wolfshot? 3 Is it he pursues you?

BAUMGARTEN.

He'll ne'er hunt man again; I've settled him.

ALL (starting back).

Now, God forgive you, what is this you've done!

BAUMGARTEN.

What every free man in my place had done.

I have but used mine own good household right

'Gainst him that would have wronged my wife—my honor.

KUONI.

And has he wronged you in your honor, then?

BAUMGARTEN.

That he did not fulfil his foul desire

Is due to God and to my trusty axe.

WERNI.

You've cleft his skull, then, have you, with your axe?

KUONI.

Oh, tell us all! You've time enough, before

The boat can be unfastened from its moorings.

BAUMGARTEN.

When I was in the forest, felling timber,

My wife came running out in mortal fear:

"The seneschal," she said, "was in my house,

Had ordered her to get a bath prepared,

And thereupon had taken unseemly freedoms,

From which she rid herself and flew to me."

Armed as I was I sought him, and my axe

Has given his bath a bloody benediction.

WERNI.

And you did well; no man can blame the deed.

KUONI.

The tyrant! Now he has his just reward!

We men of Unterwald have owed it long.

BAUMGARTEN.

The deed got wind, and now they're in pursuit.

Heavens! whilst we speak, the time is flying fast.

[It begins to thunder.

KUONI.

Quick, ferrymen, and set the good man over.

RUODI.

Impossible! a storm is close at hand,

Wait till it pass! You must.

BAUMGARTEN.

Almighty heavens!

I cannot wait; the least delay is death.

KUONI (to the fisherman).

Push out. God with you! We should help our neighbors;

The like misfortune may betide us all.

[Thunder and the roaring of the wind.

RUODI.

The south wind's up! 4 See how the lake is rising!

I cannot steer against both storm and wave.

BAUMGARTEN (clasping him by the knees).

God so help you, as now you pity me!

WERNI.

His life's at stake. Have pity on him, man!

KUONI.

He is a father: has a wife and children.

[Repeated peals of thunder.

RUODI.

What! and have I not, then, a life to lose,

A wife and child at home as well as he?

See, how the breakers foam, and toss, and whirl,

And the lake eddies up from all its depths!

Right gladly would I save the worthy man,

But 'tis impossible, as you must see.

BAUMGARTEN (still kneeling).

Then must I fall into the tyrant's hands,

And with the port of safety close in sight!

Yonder it lies! My eyes can measure it,

My very voice can echo to its shores.

There is the boat to carry me across,

Yet must I lie here helpless and forlorn.

KUONI.

Look! who comes here?

RUODI.

'Tis Tell, brave Tell, of Buerglen. 5

[Enter TELL, with a crossbow.

TELL.

Who is the man that here implores for aid?

KUONI.

He is from Alzellen, and to guard his honor

From touch of foulest shame, has slain the Wolfshot!

The imperial seneschal, who dwelt at Rossberg.

The viceroy's troopers are upon his heels;

He begs the boatman here to take him over,

But he, in terror of the storm, refuses.

RUODI.

Well, there is Tell can steer as well as I.

He'll be my judge, if it be possible.

[Violent peals of thunder—the lake becomes more tempestuous.

Am I to plunge into the jaws of hell?

I should be mad to dare the desperate act.

TELL.

The brave man thinks upon himself the last.

Put trust in God, and help him in his need!

RUODI.

Safe in the port, 'tis easy to advise.

There is the boat, and there the lake! Try you!

TELL.

The lake may pity, but the viceroy will not.

Come, venture, man!

SHEPHERD and HUNTSMAN.

Oh, save him! save him! save him!

RUODI.

Though 'twere my brother, or my darling child,

I would not go. It is St. Simon's day,

The lake is up, and calling for its victim.

TELL.

Naught's to be done with idle talking here.

Time presses on—the man must be assisted.

Say, boatman, will you venture?

RUODI.

No; not I.

TELL.

In God's name, then, give me the boat! I will

With my poor strength, see what is to be done!

KUONI.

Ha, noble Tell!

WERNI.

That's like a gallant huntsman!

BAUMGARTEN.

You are my angel, my preserver, Tell.

TELL.

I may preserve you from the viceroy's power

But from the tempest's rage another must.

Yet you had better fall into God's hands,

Than into those of men.

[To the herdsman.

Herdsman, do thou

Console my wife, should aught of ill befall me.

I do but what I may not leave undone.

[He leaps into the boat.

KUONI (to the fisherman).

A pretty man to be a boatman, truly!

What Tell could risk you dared not venture on.

RUODI.

Far better men than I would not ape Tell.

There does not live his fellow 'mong the mountains.

WERNI (who has ascended a rock).

He pushes off. God help thee now, brave sailor!

Look how his bark is reeling on the waves!

KUONI (on the shore).

The surge has swept clean over it. And now

'Tis out of sight. Yet stay, there 'tis again

Stoutly he stems the breakers, noble fellow!

SEPPI.

Here come the troopers hard as they can ride!

KUONI.

Heavens! so they do! Why, that was help, indeed.

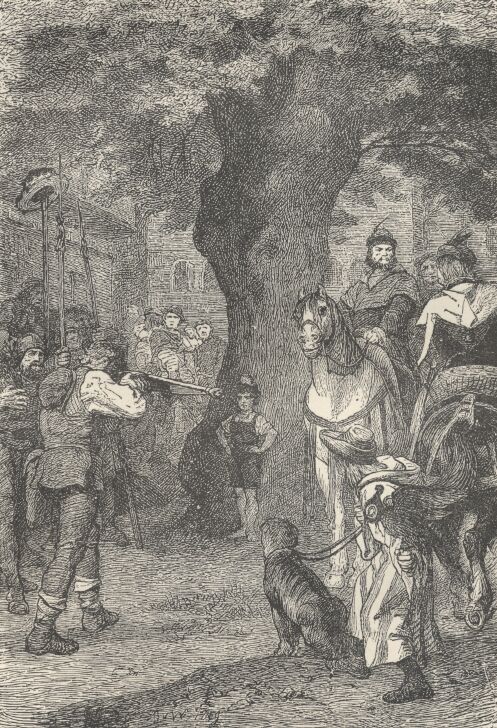

[Enter a troop of horsemen.

FIRST HORSEMAN.

Give up the murderer! You have him here!

SECOND HORSEMAN.

This way he came! 'Tis useless to conceal him!

RUODI and KUONI.

Whom do you mean?

FIRST HORSEMAN (discovering the boat).

The devil! What do I see?

WERNI (from above).

Is't he in yonder boat ye seek? Ride on,

If you lay to, you may o'ertake him yet.

SECOND HORSEMAN.

Curse on you, he's escaped!

FIRST HORSEMAN (to the shepherd and fisherman).

You helped him off,

And you shall pay for it. Fall on their herds!

Down with the cottage! burn it! beat it down!

[They rush off.

SEPPI (hurrying after them).

Oh, my poor lambs!

KUONI (following him).

Unhappy me, my herds!

WERNI.

The tyrants!

RUODI (wringing his hands).

Righteous Heaven! Oh, when will come

Deliverance to this devoted land?

[Exeunt severally.

A lime-tree in front of STAUFFACHER'S house at Steinen,

in Schwytz, upon the public road, near a bridge.

WERNER STAUFFACHER and PFEIFFER, of Lucerne, enter into

conversation.

PFEIFFER.

Ay, ay, friend Stauffacher, as I have said,

Swear not to Austria, if you can help it.

Hold by the empire stoutly as of yore,

And God preserve you in your ancient freedom!

[Presses his hand warmly and is going.

STAUFFACHER.

Wait till my mistress comes. Now do! You are

My guest in Schwytz—I in Lucerne am yours.

PFEIFFER.

Thanks! thanks! But I must reach Gersau to-day.

Whatever grievances your rulers' pride

And grasping avarice may yet inflict,

Bear them in patience—soon a change may come.

Another emperor may mount the throne.

But Austria's once, and you are hers forever.

[Exit.

[STAUFEACHER sits down sorrowfully upon a bench

under the lime tree. Gertrude, his wife, enters,

and finds him in this posture. She places herself

near him, and looks at him for some time in silence.

GERTRUDE.

So sad, my love! I scarcely know thee now.

For many a day in silence I have marked

A moody sorrow furrowing thy brow.

Some silent grief is weighing on thy heart;

Trust it to me. I am thy faithful wife,

And I demand my half of all thy cares.

[STAUFFACHER gives her his hand and is silent.

Tell me what can oppress thy spirits thus?

Thy toil is blest—the world goes well with thee—

Our barns are full—our cattle many a score;

Our handsome team of sleek and well-fed steeds,

Brought from the mountain pastures safely home,

To winter in their comfortable stalls.

There stands thy house—no nobleman's more fair!

'Tis newly built with timber of the best,

All grooved and fitted with the nicest skill;

Its many glistening windows tell of comfort!

'Tis quartered o'er with scutcheons of all hues,

And proverbs sage, which passing travellers

Linger to read, and ponder o'er their meaning.

STAUFFACHER.

The house is strongly built, and handsomely,

But, ah! the ground on which we built it totters.

GERTRUDE.

Tell me, dear Werner, what you mean by that?

STAUFFACHER.

No later since than yesterday, I sat

Beneath this linden, thinking with delight,

How fairly all was finished, when from Kuessnacht

The viceroy and his men came riding by.

Before this house he halted in surprise:

At once I rose, and, as beseemed his rank,

Advanced respectfully to greet the lord,

To whom the emperor delegates his power,

As judge supreme within our Canton here.

"Who is the owner of this house?" he asked,

With mischief in his thoughts, for well he knew.

With prompt decision, thus I answered him:

"The emperor, your grace—my lord and yours,

And held by one in fief." On this he answered,

"I am the emperor's viceregent here,

And will not that each peasant churl should build

At his own pleasure, bearing him as freely

As though he were the master in the land.

I shall make bold to put a stop to this!"

So saying he, with menaces, rode off,

And left me musing, with a heavy heart,

On the fell purpose that his words betrayed.

GERTRUDE.

Mine own dear lord and husband! Wilt thou take

A word of honest counsel from thy wife?

I boast to be the noble Iberg's child,

A man of wide experience. Many a time,

As we sat spinning in the winter nights,

My sisters and myself, the people's chiefs

Were wont to gather round our father's hearth,

To read the old imperial charters, and

To hold sage converse on the country's weal.

Then heedfully I listened, marking well

What or the wise men thought, or good man wished,

And garnered up their wisdom in my heart.

Hear then, and mark me well; for thou wilt see,

I long have known the grief that weighs thee down.

The viceroy hates thee, fain would injure thee,

For thou hast crossed his wish to bend the Swiss

In homage to this upstart house of princes,

And kept them stanch, like their good sires of old,

In true allegiance to the empire. Say.

Is't not so, Werner? Tell nee, am I wrong?

STAUFFACHER.

'Tis even so. For this doth Gessler hate me.

GERTRUDE.

He burns with envy, too, to see thee living

Happy and free on thy inheritance,

For he has none. From the emperor himself

Thou holdest in fief the lands thy fathers left thee.

There's not a prince in the empire that can show

A better title to his heritage;

For thou hast over thee no lord but one,

And he the mightiest of all Christian kings.

Gessler, we know, is but a younger son,

His only wealth the knightly cloak he wears;

He therefore views an honest man's good fortune

With a malignant and a jealous eye.

Long has he sworn to compass thy destruction

As yet thou art uninjured. Wilt thou wait

Till he may safely give his malice scope?

A wise man would anticipate the blow.

STAUFFACHER.

What's to be done?

GERTRUDE.

Now hear what I advise.

Thou knowest well, how here with us in Schwytz,

All worthy men are groaning underneath

This Gessler's grasping, grinding tyranny.

Doubt not the men of Unterwald as well,

And Uri, too, are chafing like ourselves,

At this oppressive and heart-wearying yoke.

For there, across the lake, the Landenberg

Wields the same iron rule as Gessler here—

No fishing-boat comes over to our side

But brings the tidings of some new encroachment,

Some outrage fresh, more grievous than the last.

Then it were well that some of you—true men—

Men sound at heart, should secretly devise

How best to shake this hateful thraldom off.

Well do I know that God would not desert you,

But lend his favor to the righteous cause.

Hast thou no friend in Uri, say, to whom

Thou frankly may'st unbosom all thy thoughts?

STAUFFACHER.

I know full many a gallant fellow there,

And nobles, too,—great men, of high repute,

In whom I can repose unbounded trust.

[Rising.

Wife! What a storm of wild and perilous thoughts

Hast thou stirred up within my tranquil breast?

The darkest musings of my bosom thou

Hast dragged to light, and placed them full before me,

And what I scarce dared harbor e'en in thought,

Thou speakest plainly out, with fearless tongue.

But hast thou weighed well what thou urgest thus?

Discord will come, and the fierce clang of arms,

To scare this valley's long unbroken peace,

If we, a feeble shepherd race, shall dare

Him to the fight that lords it o'er the world.

Even now they only wait some fair pretext

For setting loose their savage warrior hordes,

To scourge and ravage this devoted land,

To lord it o'er us with the victor's rights,

And 'neath the show of lawful chastisement,

Despoil us of our chartered liberties.

GERTRUDE.

You, too, are men; can wield a battle-axe

As well as they. God ne'er deserts the brave.

STAUFFACHER.

Oh wife! a horrid, ruthless fiend is war,

That strikes at once the shepherd and his flock.

GERTRUDE.

Whate'er great heaven inflicts we must endure;

No heart of noble temper brooks injustice.

STAUFFACHER.

This house—thy pride—war, unrelenting war,

Will burn it down.

GERTRUDE.

And did I think this heart

Enslaved and fettered to the things of earth,

With my own hand I'd hurl the kindling torch.

STAUFFACHER.

Thou hast faith in human kindness, wife; but war

Spares not the tender infant in its cradle.

GERTRUDE.

There is a friend to innocence in heaven

Look forward, Werner—not behind you, now!

STAUFFACHER.

We men may perish bravely, sword in hand;

But oh, what fate, my Gertrude, may be thine?

GERTRUDE.

None are so weak, but one last choice is left.

A spring from yonder bridge, and I am free!

STAUFFACHER (embracing her).

Well may he fight for hearth and home that clasps

A heart so rare as thine against his own!

What are the hosts of emperors to him!

Gertrude, farewell! I will to Uri straight.

There lives my worthy comrade, Walter Furst,

His thoughts and mine upon these times are one.

There, too, resides the noble Banneret

Of Attinghaus. High though of blood he be,

He loves the people, honors their old customs.

With both of these I will take counsel how

To rid us bravely of our country's foe.

Farewell! and while I am away, bear thou

A watchful eye in management at home.

The pilgrim journeying to the house of God,

And pious monk, collecting for his cloister,

To these give liberally from purse and garner.

Stauffacher's house would not be hid. Right out

Upon the public way it stands, and offers

To all that pass an hospitable roof.

[While they are retiring, TELL enters with BAUMGARTEN.

TELL.

Now, then, you have no further need of me.

Enter yon house. 'Tis Werner Stauffacher's,

A man that is a father to distress.

See, there he is himself! Come, follow me.

[They retire up. Scene changes.

A common near Altdorf. On an eminence in the background a castle

in progress of erection, and so far advanced that the outline of the

whole may be distinguished. The back part is finished; men are

working at the front. Scaffolding, on which the workmen are going

up and down. A slater is seen upon the highest part of the roof.—

All is bustle and activity.

TASKMASTER, MASON, WORKMEN, and LABORERS.

TASKMASTER (with a stick, urging on the workmen).

Up, up! You've rested long enough. To work!

The stones here, now the mortar, and the lime!

And let his lordship see the work advanced

When next he comes. These fellows crawl like snails!

[To two laborers with loads.

What! call ye that a load? Go, double it.

Is this the way ye earn your wages, laggards?

FIRST WORKMAN.

'Tis very hard that we must bear the stones,

To make a keep and dungeon for ourselves!

TASKMASTER.

What's that you mutter? 'Tis a worthless race,

And fit for nothing but to milk their cows,

And saunter idly up and down the mountains.

OLD MAN (sinks down exhausted).

I can no more.

TASKMASTER (shaking him).

Up, up, old man, to work!

FIRST WORKMAN.

Have you no bowels of compassion, thus

To press so hard upon a poor old man,

That scarce can drag his feeble limbs along?

MASTER MASON and WORKMEN.

Shame, shame upon you—shame! It cries to heaven!

TASKMASTER.

Mind your own business. I but do my duty.

FIRST WORKMAN.

Pray, master, what's to be the name of this

Same castle when 'tis built?

TASKMASTER.

The keep of Uri;

For by it we shall keep you in subjection.

WORKMEN.

The keep of Uri.

TASKMASTER.

Well, why laugh at that?

SECOND WORKMAN.

So you'll keep Uri with this paltry place!

FIRST WORKMAN.

How many molehills such as that must first

Be piled above each other ere you make

A mountain equal to the least in Uri?

[TASKMASTER retires up the stage.

MASTER MASON.

I'll drown the mallet in the deepest lake,

That served my hand on this accursed pile.

[Enter TELL and STAUFFACHER.

STAUFFACHER.

Oh, that I had not lived to see this sight!

TELL.

Here 'tis not good to be. Let us proceed.

STAUFFACHER.

Am I in Uri, in the land of freedom?

MASTER MASON.

Oh, sir, if you could only see the vaults

Beneath these towers. The man that tenants them

Will never hear the cock crow more.

STAUFFACHER.

O God!

MASTER MASON.

Look at these ramparts and these buttresses,

That seem as they were built to last forever.

TELL.

Hands can destroy whatever hands have reared.

[Pointing to the mountains.

That house of freedom God hath built for us.

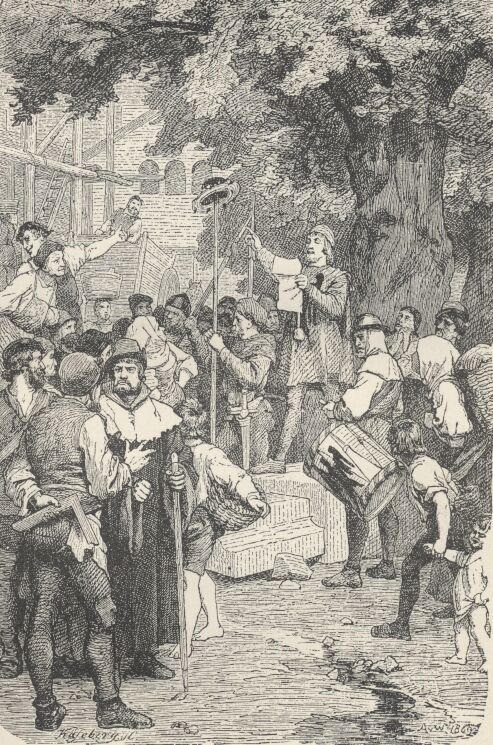

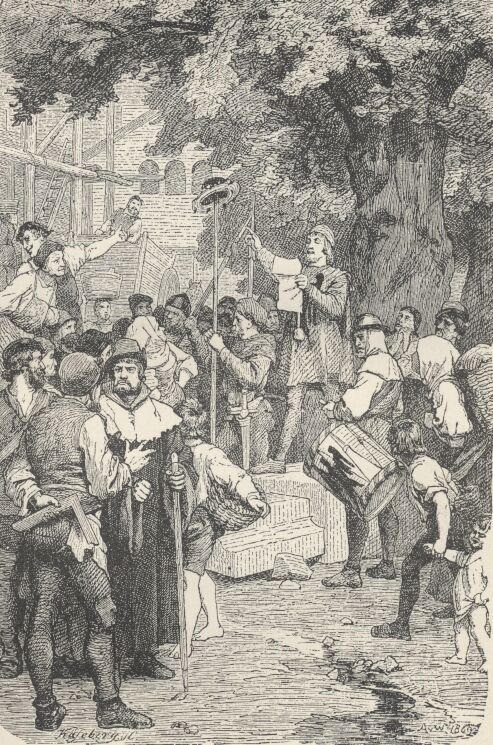

[A drum is heard. People enter bearing a cap upon a

pole, followed by a crier. Women and children thronging

tumultuously after them.

FIRST WORKMAN.

What means the drum? Give heed!

MASTER MASON.

Why here's a mumming!

And look, the cap,—what can they mean by that?

CRIER.

In the emperor's name, give ear!

WORKMEN.

Hush! silence! hush!

CRIER.

Ye men of Uri, ye do see this cap!

It will be set upon a lofty pole

In Altdorf, in the market-place: and this

Is the lord governor's good will and pleasure,

The cap shall have like honor as himself,

And all shall reverence it with bended knee,

And head uncovered; thus the king will know

Who are his true and loyal subjects here:

His life and goods are forfeit to the crown,

That shall refuse obedience to the order.

[The people burst out into laughter. The drum beats,

and the procession passes on.

FIRST WORKMAN.

A strange device to fall upon, indeed!

Do reverence to a cap! a pretty farce!

Heard ever mortal anything like this?

MASTER MASON.

Down to a cap on bended knee, forsooth!

Rare jesting this with men of sober sense!

FIRST WORKMAN.

Nay, were it but the imperial crown, indeed!

But 'tis the cap of Austria! I've seen it

Hanging above the throne in Gessler's hall.

MASTER MASON.

The cap of Austria! Mark that! A snare

To get us into Austria's power, by heaven!

WORKMEN.

No freeborn man will stoop to such disgrace.

MASTER MASON.

Come—to our comrades, and advise with them!

[They retire up.

TELL (to STAUFFACHER).

You see how matters stand: Farewell, my friend!

STAUFFACHER.

Whither away? Oh, leave us not so soon.

TELL.

They look for me at home. So fare ye well.

STAUFFACHER.

My heart's so full, and has so much to tell you.

TELL.

Words will not make a heart that's heavy light.

STAUFFACHER.

Yet words may possibly conduct to deeds.

TELL.

All we can do is to endure in silence.

STAUFFACHER.

But shall we bear what is not to be borne?

TELL.

Impetuous rulers have the shortest reigns.

When the fierce south wind rises from his chasms,

Men cover up their fires, the ships in haste

Make for the harbor, and the mighty spirit

Sweeps o'er the earth, and leaves no trace behind.

Let every man live quietly at home;

Peace to the peaceful rarely is denied.

STAUFFACHER.

And is it thus you view our grievances?

TELL.

The serpent stings not till it is provoked.

Let them alone; they'll weary of themselves,

Whene'er they see we are not to be roused.

STAUFFACHER.

Much might be done—did we stand fast together.

TELL.

When the ship founders, he will best escape

Who seeks no other's safety but his own.

STAUFFACHER.

And you desert the common cause so coldly?

TELL.

A man can safely count but on himself!

STAUFFACHER.

Nay, even the weak grow strong by union.

TELL.

But the strong man is the strongest when alone.

STAUFFACHER.

Your country, then, cannot rely on you

If in despair she rise against her foes.

TELL.

Tell rescues the lost sheep from yawning gulfs:

Is he a man, then, to desert his friends?

Yet, whatsoe'er you do, spare me from council!

I was not born to ponder and select;

But when your course of action is resolved,

Then call on Tell; you shall not find him fail.

[Exeunt severally. A sudden tumult is heard around the scaffolding.

MASTER MASON (running in).

What's wrong?

FIRST WORKMAN (running forward).

The slater's fallen from the roof.

BERTHA (rushing in).

Is he dashed to pieces? Run—save him, help!

If help be possible, save him! Here is gold.

[Throws her trinkets among the people.

MASTER MASON.

Hence with your gold,—your universal charm,

And remedy for ill! When you have torn

Fathers from children, husbands from their wives,

And scattered woe and wail throughout the land,

You think with gold to compensate for all.

Hence! Till we saw you we were happy men;

With you came misery and dark despair.

BERTHA (to the TASKMASTER, who has returned).

Lives he?

[TASKMASTER shakes his head.

Ill-fated towers, with curses built,

And doomed with curses to be tenanted!

[Exit.

The House of WALTER FURST.

WALTER FURST and ARNOLD

VON MELCHTHAL enter simultaneously at different sides.

MELCHTHAL.

Good Walter Furst.

FURST.

If we should be surprised!

Stay where you are. We are beset with spies.

MELCHTHAL.

Have you no news for me from Unterwald?

What of my father? 'Tis not to be borne,

Thus to be pent up like a felon here!

What have I done of such a heinous stamp,

To skulk and hide me like a murderer?

I only laid my staff across the fingers

Of the pert varlet, when before my eyes,

By order of the governor, he tried

To drive away my handsome team of oxen.

FURST.

You are too rash by far. He did no more

Than what the governor had ordered him.

You had transgressed, and therefore should have paid

The penalty, however hard, in silence.

MELCHTHAL.

Was I to brook the fellow's saucy words?

"That if the peasant must have bread to eat;

Why, let him go and draw the plough himself!"

It cut me to the very soul to see

My oxen, noble creatures, when the knave

Unyoked them from the plough. As though they felt

The wrong, they lowed and butted with their horns.

On this I could contain myself no longer,

And, overcome by passion, struck him down.

FURST.

Oh, we old men can scarce command ourselves!

And can we wonder youth shall break its bounds?

MELCHTHAL.

I'm only sorry for my father's sake!

To be away from him, that needs so much

My fostering care! The governor detests him,

Because he hath, whene'er occasion served,

Stood stoutly up for right and liberty.

Therefore they'll bear him hard—the poor old man!

And there is none to shield him from their gripe.

Come what come may, I must go home again.

FURST.

Compose yourself, and wait in patience till

We get some tidings o'er from Unterwald.

Away! away! I hear a knock! Perhaps

A message from the viceroy! Get thee in!

You are not safe from Landenberger's 6 arm

In Uri, for these tyrants pull together.

MELCHTHAL.

They teach us Switzers what we ought to do.

FURST.

Away! I'll call you when the coast is clear.

[MELCHTHAL retires.

Unhappy youth! I dare not tell him all

The evil that my boding heart predicts!

Who's there? The door ne'er opens but I look

For tidings of mishap. Suspicion lurks

With darkling treachery in every nook.

Even to our inmost rooms they force their way,

These myrmidons of power; and soon we'll need

To fasten bolts and bars upon our doors.

[He opens the door and steps back in surprise as

WERNER STAUFFACHER enters.

What do I see? You, Werner? Now, by Heaven!

A valued guest, indeed. No man e'er set

His foot across this threshold more esteemed.

Welcome! thrice welcome, Werner, to my roof!

What brings you here? What seek you here in Uri?

STAUFFACHER (shakes FURST by the hand).

The olden times and olden Switzerland.

FURST.

You bring them with you. See how I'm rejoiced,

My heart leaps at the very sight of you.

Sit down—sit down, and tell me how you left

Your charming wife, fair Gertrude? Iberg's child,

And clever as her father. Not a man,

That wends from Germany, by Meinrad's Cell, 7

To Italy, but praises far and wide

Your house's hospitality. But say,

Have you come here direct from Flueelen,

And have you noticed nothing on your way,

Before you halted at my door?

STAUFFACHER (sits down).

I saw

A work in progress, as I came along,

I little thought to see—that likes me ill.

FURST.

O friend! you've lighted on my thought at once.

STAUFFACHER.

Such things in Uri ne'er were known before.

Never was prison here in man's remembrance,

Nor ever any stronghold but the grave.

FURST.

You name it well. It is the grave of freedom.

STAUFFACHER.

Friend, Walter Furst, I will be plain with you.

No idle curiosity it is

That brings me here, but heavy cares. I left

Thraldom at home, and thraldom meets me here.

Our wrongs, e'en now, are more than we can bear.

And who shall tell us where they are to end?

From eldest time the Switzer has been free,

Accustomed only to the mildest rule.

Such things as now we suffer ne'er were known

Since herdsmen first drove cattle to the hills.

FURST.

Yes, our oppressions are unparalleled!

Why, even our own good lord of Attinghaus,

Who lived in olden times, himself declares

They are no longer to be tamely borne.

STAUFFACHER.

In Unterwalden yonder 'tis the same;

And bloody has the retribution been.

The imperial seneschal, the Wolfshot, who

At Rossberg dwelt, longed for forbidden fruits—

Baumgarten's wife, that lives at Alzellen,

He wished to overcome in shameful sort,

On which the husband slew him with his axe.

FURST.

Oh, Heaven is just in all its judgments still!

Baumgarten, say you? A most worthy man.

Has he escaped, and is he safely hid?

STAUFFACHER.

Your son-in-law conveyed him o'er the lake,

And he lies hidden in my house at Steinen.

He brought the tidings with him of a thing

That has been done at Sarnen, worse than all,

A thing to make the very heart run blood!

FURST (attentively).

Say on. What is it?

STAUFFACHER.

There dwells in Melchthal, then,

Just as you enter by the road from Kearns,

An upright man, named Henry of the Halden,

A man of weight and influence in the Diet.

FURST.

Who knows him not? But what of him? Proceed.

STAUFFACHER.

The Landenberg, to punish some offence,

Committed by the old man's son, it seems,

Had given command to take the youth's best pair

Of oxen from his plough: on which the lad

Struck down the messenger and took to flight.

FURST.

But the old father—tell me, what of him?

STAUFFACHER.

The Landenberg sent for him, and required

He should produce his son upon the spot;

And when the old man protested, and with truth,

That he knew nothing of the fugitive,

The tyrant called his torturers.

FURST (springs up and tries to lead him to the other side).

Hush, no more!

STAUFFACHER (with increasing warmth).

"And though thy son," he cried, "Has escaped me now,

I have thee fast, and thou shalt feel my vengeance."

With that they flung the old man to the earth,

And plunged the pointed steel into his eyes.

FURST.

Merciful heavens!

MELCHTHAL (rushing out).

Into his eyes, his eyes?

STAUFFACHER (addresses himself in astonishment to WALTER FURST).

Who is this youth?

MELCHTHAL (grasping him convulsively).

Into his eyes? Speak, speak!

FURST.

Oh, miserable hour!

STAUFFACHER.

Who is it, tell me?

[STAUFFACHER makes a sign to him.

It is his son! All righteous heaven!

MELCHTHAL.

And I

Must be from thence! What! into both his eyes?

FURST.

Be calm, be calm; and bear it like a man!

MELCHTHAL.

And all for me—for my mad wilful folly!

Blind, did you say? Quite blind—and both his eyes?

STAUFFACHER.

Even so. The fountain of his sight's dried up.

He ne'er will see the blessed sunshine more.

FURST.

Oh, spare his anguish!

MELCHTHAL.

Never, never more!

[Presses his hands upon his eyes and is silent for some

moments; then turning from one to the other, speaks in a

subdued tone, broken by sobs.

O the eye's light, of all the gifts of heaven,

The dearest, best! From light all beings live—

Each fair created thing—the very plants

Turn with a joyful transport to the light,

And he—he must drag on through all his days

In endless darkness! Never more for him

The sunny meads shall glow, the flowerets bloom;

Nor shall he more behold the roseate tints

Of the iced mountain top! To die is nothing,

But to have life, and not have sight—oh, that

Is misery indeed! Why do you look

So piteously at me? I have two eyes,

Yet to my poor blind father can give neither!

No, not one gleam of that great sea of light,

That with its dazzling splendor floods my gaze.

STAUFFACHER.

Ah, I must swell the measure of your grief,

Instead of soothing it. The worst, alas!

Remains to tell. They've stripped him of his all;

Naught have they left him, save his staff, on which,

Blind and in rags, he moves from door to door.

MELCHTHAL.

Naught but his staff to the old eyeless man!

Stripped of his all—even of the light of day,

The common blessing of the meanest wretch.

Tell me no more of patience, of concealment!

Oh, what a base and coward thing am I,

That on mine own security I thought

And took no care of thine! Thy precious head

Left as a pledge within the tyrant's grasp!

Hence, craven-hearted prudence, hence! And all

My thoughts be vengeance, and the despot's blood!

I'll seek him straight—no power shall stay me now—

And at his hands demand my father's eyes.

I'll beard him 'mid a thousand myrmidons!

What's life to me, if in his heart's best blood

I cool the fever of this mighty anguish.

[He is going.

FURST.

Stay, this is madness, Melchthal! What avails

Your single arm against his power? He sits

At Sarnen high within his lordly keep,

And, safe within its battlemented walls,

May laugh to scorn your unavailing rage.

MELCHTHAL.

And though he sat within the icy domes

Of yon far Schreckhorn—ay, or higher, where

Veiled since eternity, the Jungfrau soars,

Still to the tyrant would I make my way;

With twenty comrades minded like myself,

I'd lay his fastness level with the earth!

And if none follow me, and if you all,

In terror for your homesteads and your herds,

Bow in submission to the tyrant's yoke,

I'll call the herdsmen on the hills around me,

And there beneath heaven's free and boundless roof,

Where men still feel as men, and hearts are true

Proclaim aloud this foul enormity!

STAUFFACHER (to FURST).

'Tis at its height—and are we then to wait

Till some extremity——

MELCHTHAL.

What extremity

Remains for apprehension, where men's eyes

Have ceased to be secure within their sockets?

Are we defenceless? Wherefore did we learn

To bend the crossbow—wield the battle-axe?

What living creature, but in its despair,

Finds for itself a weapon of defence?

The baited stag will turn, and with the show

Of his dread antlers hold the hounds at bay;

The chamois drags the huntsman down the abyss;

The very ox, the partner of man's toil,

The sharer of his roof, that meekly bends

The strength of his huge neck beneath the yoke,

Springs up, if he's provoked, whets his strong horn,

And tosses his tormenter to the clouds.

FURST.

If the three Cantons thought as we three do,

Something might, then, be done, with good effect.

STAUFFACHER.

When Uri calls, when Unterwald replies,

Schwytz will be mindful of her ancient league. 8

MELCHTHAL.

I've many friends in Unterwald, and none

That would not gladly venture life and limb

If fairly backed and aided by the rest.

Oh, sage and reverend fathers of this land,

Here do I stand before your riper years,

An unskilled youth whose voice must in the Diet

Still be subdued into respectful silence.

Do not, because that I am young and want

Experience, slight my counsel and my words.

'Tis not the wantonness of youthful blood

That fires my spirit; but a pang so deep

That even the flinty rocks must pity me.

You, too, are fathers, heads of families,

And you must wish to have a virtuous son

To reverence your gray hairs and shield your eyes

With pious and affectionate regard.

Do not, I pray, because in limb and fortune

You still are unassailed, and still your eyes

Revolve undimmed and sparkling in their spheres;

Oh, do not, therefore, disregard our wrongs!

Above you, too, doth hang the tyrant's sword.

You, too, have striven to alienate the land

From Austria. This was all my father's crime:

You share his guilt and may his punishment.

STAUFFACHER (to FURST).

Do then resolve! I am prepared to follow.

FURST.

First let us learn what steps the noble lords

Von Sillinen and Attinghaus propose.

Their names would rally thousands in the cause.

MELCHTHAL.

Is there a name within the Forest Mountains

That carries more respect than thine—and thine?

To names like these the people cling for help

With confidence—such names are household words.

Rich was your heritage of manly virtue,

And richly have you added to its stores.

What need of nobles? Let us do the work

Ourselves. Although we stood alone, methinks

We should be able to maintain our rights.

STAUFFACHER.

The nobles' wrongs are not so great as ours.

The torrent that lays waste the lower grounds

Hath not ascended to the uplands yet.

But let them see the country once in arms

They'll not refuse to lend a helping hand.

FURST.

Were there an umpire 'twixt ourselves and Austria,

Justice and law might then decide our quarrel.

But our oppressor is our emperor, too,

And judge supreme. 'Tis God must help us, then,

And our own arm! Be yours the task to rouse

The men of Schwytz; I'll rally friends in Uri.

But whom are we to send to Unterwald?

MELCHTHAL.

Thither send me. Whom should it more concern?

FURST.

No, Melchthal, no; thou art my guest, and I

Must answer for thy safety.

MELCHTHAL.

Let me go.

I know each forest track and mountain pass;

Friends too I'll find, be sure, on every hand,

To give me willing shelter from the foe.

STAUFFACHER.

Nay, let him go; no traitors harbor there:

For tyranny is so abhorred in Unterwald

No minions can be found to work her will.

In the low valleys, too, the Alzeller

Will gain confederates and rouse the country.

MELCHTHAL.

But how shall we communicate, and not

Awaken the suspicion of the tyrants?

STAUFFACHER.

Might we not meet at Brunnen or at Treib,

Hard by the spot where merchant-vessels land?

FURST.

We must not go so openly to work.

Hear my opinion. On the lake's left bank,

As we sail hence to Brunnen, right against

The Mytenstein, deep-hidden in the wood

A meadow lies, by shepherds called the Rootli,

Because the wood has been uprooted there.

'Tis where our Canton boundaries verge on yours;—

[To MELCHTHAL.

Your boat will carry you across from Schwytz.

[To STAUFFACHER.

Thither by lonely by-paths let us wend

At midnight and deliberate o'er our plans.

Let each bring with him there ten trusty men,

All one at heart with us; and then we may

Consult together for the general weal,

And, with God's guidance, fix our onward course.

STAUFFACHER.

So let it be. And now your true right hand!

Yours, too, young man! and as we now three men

Among ourselves thus knit our hands together

In all sincerity and truth, e'en so

Shall we three Cantons, too, together stand

In victory and defeat, in life and death.

FURST and MELCHTHAL.

In life and death.

[They hold their hands clasped together for some moments in silence.

MELCHTHAL.

Alas, my old blind father!

Thou canst no more behold the day of freedom;

But thou shalt hear it. When from Alp to Alp

The beacon-fires throw up their flaming signs,

And the proud castles of the tyrants fall,

Into thy cottage shall the Switzer burst,

Bear the glad tidings to thine ear, and o'er

Thy darkened way shall Freedom's radiance pour.

The Mansion of the BARON OF ATTINGHAUSEN. A Gothic hall,

decorated with escutcheons and helmets. The BARON, a

gray-headed man, eighty-five years old, tall, and of a

commanding mien, clad in a furred pelisse, and leaning

on a staff tipped with chamois horn. KUONI and six hinds

standing round him, with rakes and scythes. ULRICH OF RUDENZ

enters in the costume of a knight.

RUDENZ.

Uncle, I'm here! Your will?

ATTINGHAUSEN.

First let me share,

After the ancient custom of our house,

The morning-cup with these my faithful servants!

[He drinks from a cup, which is then passed round.

Time was I stood myself in field and wood,

With mine own eyes directing all their toil,

Even as my banner led them in the fight,

Now I am only fit to play the steward;

And, if the genial sun come not to me,

I can no longer seek it on the mountains.

Thus slowly, in an ever-narrowing sphere,

I move on to the narrowest and the last,

Where all life's pulses cease. I now am but

The shadow of my former self, and that

Is fading fast—'twill soon be but a name.

KUONI (offering RUDENZ the cup).

A pledge, young master!

[RUDENZ hesitates to take the cup.

Nay, sir, drink it off!

One cup, one heart! You know our proverb, sir!

ATTINGHAUSEN.

Go, children, and at eve, when work is done,

We'll meet and talk the country's business over.

[Exeunt Servants.

Belted and plumed, and all thy bravery on!

Thou art for Altdorf—for the castle, boy?

RUDENZ.

Yes, uncle. Longer may I not delay——

ATTINGHAUSEN (sitting down).

Why in such haste? Say, are thy youthful hours

Doled in such niggard measure that thou must

Be chary of then to thy aged uncle?

RUDENZ.

I see, my presence is not needed here,

I am but as a stranger in this house.

ATTINGHAUSEN (gazes fixedly at him for a considerable time).

Alas, thou art indeed! Alas, that home

To thee has grown so strange! Oh, Uly! Uly!

I scarce do know thee now, thus decked in silks,

The peacock's feather 9 flaunting in thy cap,

And purple mantle round thy shoulders flung;

Thou lookest upon the peasant with disdain,

And takest with a blush his honest greeting.

RUDENZ.

All honor due to him I gladly pay,

But must deny the right he would usurp.

ATTINGHAUSEN.

The sore displeasure of the king is resting

Upon the land, and every true man's heart

Is full of sadness for the grievous wrongs

We suffer from our tyrants. Thou alone

Art all unmoved amid the general grief.

Abandoning thy friends, thou takest thy stand

Beside thy country's foes, and, as in scorn

Of our distress, pursuest giddy joys,

Courting the smiles of princes, all the while

Thy country bleeds beneath their cruel scourge.

RUDENZ.

The land is sore oppressed; I know it, uncle.

But why? Who plunged it into this distress?

A word, one little easy word, might buy

Instant deliverance from such dire oppression,

And win the good-will of the emperor.

Woe unto those who seal the people's eyes,

And make them adverse to their country's good;

The men who, for their own vile, selfish ends,

Are seeking to prevent the Forest States

From swearing fealty to Austria's house,

As all the countries round about have done.

It fits their humor well, to take their seats

Amid the nobles on the Herrenbank; 10

They'll have the Caesar for their lord, forsooth,

That is to say, they'll have no lord at all.

ATTINGHAUSEN.

Must I hear this, and from thy lips, rash boy!

RUDENZ.

You urged me to this answer. Hear me out.

What, uncle, is the character you've stooped

To fill contentedly through life? Have you

No higher pride, than in these lonely wilds

To be the Landamman or Banneret, 11

The petty chieftain of a shepherd race?

How! Were it not a far more glorious choice

To bend in homage to our royal lord,

And swell the princely splendors of his court,

Than sit at home, the peer of your own vassals,

And share the judgment-seat with vulgar clowns?

ATTINGHAUSEN.

Ah, Uly, Uly; all too well I see,

The tempter's voice has caught thy willing ear,

And poured its subtle poison in thy heart.

RUDENZ.

Yes, I conceal it not. It doth offend

My inmost soul to hear the stranger's gibes,

That taunt us with the name of "Peasant Nobles."

Think you the heart that's stirring here can brook,

While all the young nobility around

Are reaping honor under Hapsburg's banner,

That I should loiter, in inglorious ease,

Here on the heritage my fathers left,

And, in the dull routine of vulgar toil,

Lose all life's glorious spring? In other lands

Deeds are achieved. A world of fair renown

Beyond these mountains stirs in martial pomp.

My helm and shield are rusting in the hall;

The martial trumpet's spirit-stirring blast,

The herald's call, inviting to the lists,

Rouse not the echoes of these vales, where naught

Save cowherd's horn and cattle-bell is heard,

In one unvarying, dull monotony.

ATTINGHAUSEN.

Deluded boy, seduced by empty show!

Despise the land that gave thee birth! Ashamed

Of the good ancient customs of thy sires!

The day will come, when thou, with burning tears,

Wilt long for home, and for thy native hills,

And that dear melody of tuneful herds,

Which now, in proud disgust, thou dost despise!

A day when thou wilt drink its tones in sadness,

Hearing their music in a foreign land.

Oh! potent is the spell that binds to home!

No, no, the cold, false world is not for thee.

At the proud court, with thy true heart thou wilt

Forever feel a stranger among strangers.

The world asks virtues of far other stamp

Than thou hast learned within these simple vales.

But go—go thither; barter thy free soul,

Take land in fief, become a prince's vassal,

Where thou might'st be lord paramount, and prince

Of all thine own unburdened heritage!

O, Uly, Uly, stay among thy people!

Go not to Altdorf. Oh, abandon not

The sacred cause of thy wronged native land!

I am the last of all my race. My name

Ends with me. Yonder hang my helm and shield;

They will be buried with me in the grave. 12

And must I think, when yielding up my breath,

That thou but wait'st the closing of mine eyes,

To stoop thy knee to this new feudal court,

And take in vassalage from Austria's hands

The noble lands, which I from God received

Free and unfettered as the mountain air!

RUDENZ.

'Tis vain for us to strive against the king.

The world pertains to him:—shall we alone,

In mad, presumptuous obstinacy strive

To break that mighty chain of lands, which he

Hath drawn around us with his giant grasp.

His are the markets, his the courts; his too

The highways; nay, the very carrier's horse,

That traffics on the Gotthardt, pays him toll.

By his dominions, as within a net,

We are enclosed, and girded round about.

—And will the empire shield us? Say, can it

Protect itself 'gainst Austria's growing power?

To God, and not to emperors, must we look!

What store can on their promises be placed,

When they, to meet their own necessities,

Can pawn, and even alienate the towns

That flee for shelter 'neath the eagle's wings? 13

No, uncle. It is wise and wholesome prudence,

In times like these, when faction's all abroad,

To own attachment to some mighty chief.

The imperial crown's transferred from line to line, 14

It has no memory for faithful service:

But to secure the favor of these great

Hereditary masters, were to sow

Seed for a future harvest.

ATTINGHAUSEN.

Art so wise?

Wilt thou see clearer than thy noble sires,

Who battled for fair freedom's costly gem,

With life, and fortune, and heroic arm?

Sail down the lake to Lucerne, there inquire,

How Austria's rule doth weigh the Cantons down.

Soon she will come to count our sheep, our cattle,

To portion out the Alps, e'en to their summits,

And in our own free woods to hinder us

From striking down the eagle or the stag;

To set her tolls on every bridge and gate,

Impoverish us to swell her lust of sway,

And drain our dearest blood to feed her wars.

No, if our blood must flow, let it be shed

In our own cause! We purchase liberty

More cheaply far than bondage.

RUDENZ.

What can we,

A shepherd race, against great Albert's hosts?

ATTINGHAUSEN.

Learn, foolish boy, to know this shepherd race!

I know them, I have led them on in fight—

I saw them in the battle at Favenz.

Austria will try, forsooth, to force on us

A yoke we are determined not to bear!

Oh, learn to feel from what a race thou'rt sprung!

Cast not, for tinsel trash and idle show,

The precious jewel of thy worth away.

To be the chieftain of a freeborn race,

Bound to thee only by their unbought love,

Ready to stand—to fight—to die with thee,

Be that thy pride, be that thy noblest boast!

Knit to thy heart the ties of kindred—home—

Cling to the land, the dear land of thy sires,

Grapple to that with thy whole heart and soul!

Thy power is rooted deep and strongly here,

But in yon stranger world thou'lt stand alone,

A trembling reed beat down by every blast.

Oh come! 'tis long since we have seen thee, Uly!

Tarry but this one day. Only to-day

Go not to Altdorf. Wilt thou? Not to-day!

For this one day bestow thee on thy friends.

[Takes his hand.

RUDENZ.

I gave my word. Unhand me! I am bound.

ATTINGHAUSEN (drops his hand and says sternly).

Bound, didst thou say? Oh yes, unhappy boy,

Thou art, indeed. But not by word or oath.

'Tis by the silken mesh of love thou'rt bound.

[RUDENZ turns away.

Ay, hide thee, as thou wilt. 'Tis she, I know,

Bertha of Bruneck, draws thee to the court;

'Tis she that chains thee to the emperor's service.

Thou think'st to win the noble, knightly maid,

By thy apostacy. Be not deceived.

She is held out before thee as a lure;

But never meant for innocence like thine.

RUDENZ.

No more; I've heard enough. So fare you well.

[Exit.

ATTINGHAUSEN.

Stay, Uly! Stay! Rash boy, he's gone! I can

Nor hold him back, nor save him from destruction.

And so the Wolfshot has deserted us;—

Others will follow his example soon.

This foreign witchery, sweeping o'er our hills,

Tears with its potent spell our youth away:

O luckless hour, when men and manners strange

Into these calm and happy valleys came,

To warp our primitive and guileless ways.

The new is pressing on with might. The old,

The good, the simple, fleeteth fast away.

New times come on. A race is springing up,

That think not as their fathers thought before!

What do I here? All, all are in the grave

With whom ere while I moved and held converse;

My age has long been laid beneath the sod:

Happy the man who may not live to see

What shall be done by those that follow me!

A meadow surrounded by high rocks and wooded ground. On the

rocks are tracks, with rails and ladders, by which the peasants

are afterwards seen descending. In the background the lake is

observed, and over it a moon rainbow in the early part of the scene.

The prospect is closed by lofty mountains, with glaciers rising

behind them. The stage is dark, but the lake and glaciers glisten

in the moonlight.

MELCHTHAL, BAUMGARTEN, WINKELRIED, MEYER VON SARNEN, BURKHART AM

BUHEL, ARNOLD VON SEWA, KLAUS VON DER FLUE, and four other peasants,

all armed.

MELCHTHAL (behind the scenes).

The mountain pass is open. Follow me

I see the rock, and little cross upon it:

This is the spot; here is the Rootli.

[They enter with torches.

WINKELRIED.

Hark!

SEWA.

The coast is clear.

MEYER.

None of our comrades come?

We are the first, we Unterwaldeners.

MELCHTHAL.

How far is't in the night?

BAUMGARTEN.

The beacon watch

Upon the Selisberg has just called two.

[A bell is heard at a distance.

MEYER.

Hush! Hark!

BUHEL.

The forest chapel's matin bell

Chimes clearly o'er the lake from Switzerland.

FLUE.

The air is clear, and bears the sound so far.

MELCHTHAL.

Go, you and you, and light some broken boughs,

Let's bid them welcome with a cheerful blaze.

[Two peasants exeunt.

SEWA.

The moon shines fair to-night. Beneath its beams

The lake reposes, bright as burnished steel.

BUHEL.

They'll have an easy passage.

WINKELRIED (pointing to the lake).

Ha! look there!

See you nothing?

MEYER.

What is it? Ay, indeed!

A rainbow in the middle of the night.

MELCHTHAL.

Formed by the bright reflection of the moon!

FLUE.

A sign most strange and wonderful, indeed!

Many there be who ne'er have seen the like.

SEWA.

'Tis doubled, see, a paler one above!

BAUMGARTEN.

A boat is gliding yonder right beneath it.

MELCHTHAL.

That must be Werner Stauffacher! I knew

The worthy patriot would not tarry long.

[Goes with BAUMGARTEN towards the shore.

MEYER.

The Uri men are like to be the last.

BUHEL.

They're forced to take a winding circuit through

The mountains; for the viceroy's spies are out.

[In the meanwhile the two peasants have kindled a fire

in the centre of the stage.

MELCHTHAL (on the shore).

Who's there? The word?

STAUFFACHER (from below).

Friends of the country.

[All retire up the stage, towards the party landing from the boat.

Enter STAUFFACHER, ITEL, REDING, HANS AUF DER MAUER, JORG IM HOPE,

CONRAD HUNN, ULRICH DER SCHMIDT, JOST VON WEILER, and three other

peasants, armed.

ALL.

Welcome!

[While the rest remain behind exchanging greetings, MELCHTHAL comes

forward with STAUFFACHER.

MELCHTHAL.

Oh, worthy Stauffacher, I've looked but now

On him, who could not look on me again.

I've laid my hands upon his rayless eyes,

And on their vacant orbits sworn a vow

Of vengeance, only to be cooled in blood.

STAUFFACHER.

Speak not of vengeance. We are here to meet

The threatened evil, not to avenge the past.

Now tell me what you've done, and what secured,

To aid the common cause in Unterwald.

How stands the peasantry disposed, and how

Yourself escaped the wiles of treachery?

MELCHTHAL.

Through the Surenen's fearful mountain chain,

Where dreary ice-fields stretch on every side,

And sound is none, save the hoarse vulture's cry,

I reached the Alpine pasture, where the herds

From Uri and from Engelberg resort,

And turn their cattle forth to graze in common.

Still as I went along, I slaked my thirst

With the coarse oozings of the lofty glacier,

That through the crevices come foaming down,

And turned to rest me in the herdsman's cots, 15

Where I was host and guest, until I gained

The cheerful homes and social haunts of men.

Already through these distant vales had spread

The rumor of this last atrocity;

And wheresoe'er I went, at every door,

Kind words and gentle looks were there to greet me.

I found these simple spirits all in arms

Against our rulers' tyrannous encroachments.

For as their Alps through each succeeding year

Yield the same roots,—their streams flow ever on

In the same channels,—nay, the clouds and winds

The selfsame course unalterably pursue,

So have old customs there, from sire to son,

Been handed down, unchanging and unchanged;

Nor will they brook to swerve or turn aside

From the fixed, even tenor of their life.

With grasp of their hard hands they welcomed me—

Took from the walls their rusty falchions down—

And from their eyes the soul of valor flashed

With joyful lustre, as I spoke those names,

Sacred to every peasant in the mountains,

Your own and Walter Fuerst's. Whate'er your voice

Should dictate as the right they swore to do;

And you they swore to follow e'en to death.

So sped I on from house to house, secure

In the guest's sacred privilege—and when

I reached at last the valley of my home,

Where dwell my kinsmen, scattered far and near—

And when I found my father stripped and blind,

Upon the stranger's straw, fed by the alms

Of charity——

STAUFFACHER.

Great heaven!

MELCHTHAL.

Yet wept I not!

No—not in weak and unavailing tears

Spent I the force of my fierce, burning anguish;

Deep in my bosom, like some precious treasure,

I locked it fast, and thought on deeds alone.

Through every winding of the hills I crept—

No valley so remote but I explored it;

Nay, even at the glacier's ice-clad base,

I sought and found the homes of living men;

And still, where'er my wandering footsteps turned,

The self-same hatred of these tyrants met me.

For even there, at vegetation's verge,

Where the numbed earth is barren of all fruits,

There grasping hands had been stretched forth for plunder.

Into the hearts of all this honest race,

The story of my wrongs struck deep, and now

They to a man are ours; both heart and hand.

Great things, indeed, you've wrought in little time.

MELCHTHAL.

I did still more than this. The fortresses,

Rossberg and Sarnen, are the country's dread;

For from behind their rocky walls the foe

Swoops, as the eagle from his eyrie, down,

And, safe himself, spreads havoc o'er the land.

With my own eyes I wished to weigh its strength,

So went to Sarnen, and explored the castle.

STAUFFACHER.

How! Risk thyself even in the tiger's den?

MELCHTHAL.

Disguised in pilgrim's weeds I entered it;

I saw the viceroy feasting at his board—

Judge if I'm master of myself or no!

I saw the tyrant, and I slew him not!

STAUFFACHER.

Fortune, indeed, has smiled upon your boldness.

[Meanwhile the others have arrived and join MELCHTHAL

and STAUFFACHER.

Yet tell me now, I pray, who are the friends,

The worthy men, who came along with you?

Make me acquainted with them, that we may

Speak frankly, man to man, and heart to heart.

MEYER.

In the three Cantons, who, sir, knows not you?

Meyer of Sarnen is my name; and this

Is Struth of Winkelried, my sister's son.

STAUFFACHER.

No unknown name. A Winkelried it was

Who slew the dragoon in the fen at Weiler,

And lost his life in the encounter, too.

WINKELRIED.

That, Master Stauffacher, was my grandfather.

MELCHTHAL (pointing to two peasants).

These two are men belonging to the convent

Of Engelberg, and live behind the forest.

You'll not think ill of them, because they're serfs,

And sit not free upon the soil, like us.

They love the land, and bear a good repute.

STAUFFACHER (to them).

Give me your hands. He has good cause for thanks,

That unto no man owes his body's service.

But worth is worth, no matter where 'tis found.

HUNN.

That is Herr Reding, sir, our old Landamman.

MEYER.

I know him well. There is a suit between us,

About a piece of ancient heritage.

Herr Reding, we are enemies in court,

Here we are one.

[Shakes his hand.

STAUFFACHER.

That's well and bravely said.

WINKELRIED.

Listen! They come. Hark to the horn of Uri!

[On the right and left armed men are seen descending

the rocks with torches.

MAUER.

Look, is not that God's pious servant there?

A worthy priest! The terrors of the night,

And the way's pains and perils scare not him,

A faithful shepherd caring for his flock.

BAUMGARTEN.

The Sacrist follows him, and Walter Fuerst.

But where is Tell? I do not see him there.

[WALTER FURST, ROSSELMANN the Pastor, PETERMANN the Sacrist,

KUONI the Shepherd, WERNI the huntsman, RUODI the Fisherman,

and five other countrymen, thirty-three in all, advance and

take their places round the fire.

FURST.

Thus must we, on the soil our fathers left us,

Creep forth by stealth to meet like murderers,

And in the night, that should their mantle lend

Only to crime and black conspiracy,

Assert our own good rights, which yet are clear

As is the radiance of the noonday sun.

MELCHTHAL.

So be it. What is woven in gloom of night

Shall free and boldly meet the morning light.

ROSSELMANN.

Confederates! listen to the words which God

Inspires my heart withal. Here we are met

To represent the general weal. In us

Are all the people of the land convened.

Then let us hold the Diet, as of old,

And as we're wont in peaceful times to do.

The time's necessity be our excuse

If there be aught informal in this meeting.

Still, wheresoe'er men strike for justice, there

Is God, and now beneath his heaven we stand.

STAUFFACHER.

'Tis well advised. Let us, then, hold the Diet

According to our ancient usages.

Though it be night there's sunshine in our cause.

MELCHTHAL.

Few though our numbers be, the hearts are here

Of the whole people; here the best are met.

HUNN.

The ancient books may not be near at hand,

Yet are they graven in our inmost hearts.

ROSSELMANN.

'Tis well. And now, then, let a ring be formed,

And plant the swords of power within the ground. 16

MAUER.

Let the Landamman step into his place,

And by his side his secretaries stand.

SACRIST.

There are three Cantons here. Which hath the right

To give the head to the united council?

Schwytz may contest the dignity with Uri,

We Unterwaldeners enter not the field.

MELCHTHAL.

We stand aside. We are not suppliants here,

Invoking aid from our more potent friends.

STAUFFACHER.

Let Uri have the sword. Her banner takes

In battle the precedence of our own.

FURST.

Schwytz, then, must share the honor of the sword;

For she's the honored ancestor of all.

ROSSELMANN.

Let me arrange this generous controversy.

Uri shall lead in battle—Schwytz in council.

FURST (gives STAUFFACHER his hand).

Then take your place.

STAUFFACHER.

Not I. Some older man.

HOFE.

Ulrich, the smith, is the most aged here.

MAUER.

A worthy man, but he is not a freeman;

No bondman can be judge in Switzerland.

STAUFFACHER.

Is not Herr Reding here, our old Landamman?

Where can we find a worthier man than he?

FURST.

Let him be Amman and the Diet's chief?

You that agree with me hold up your hands!

[All hold up their right hands.

REDING (stepping into the centre).

I cannot lay my hands upon the books;

But by yon everlasting stars I swear

Never to swerve from justice and the right.

[The two swords are placed before him, and a circle formed;

Schwytz in the centre, Uri on his right, Unterwald on his left.

REDING (resting on his battle-sword).

Why, at the hour when spirits walk the earth,

Meet the three Cantons of the mountains here,

Upon the lake's inhospitable shore?

And what the purport of the new alliance

We here contract beneath the starry heaven?

STAUFFACHER (entering the circle).

No new alliance do we now contract,

But one our fathers framed, in ancient times,

We purpose to renew! For know, confederates,

Though mountain ridge and lake divide our bounds,

And every Canton's ruled by its own laws,

Yet are we but one race, born of one blood,

And all are children of one common home.

WINKELRIED.

Then is the burden of our legends true,

That we came hither from a distant land?

Oh, tell us what you know, that our new league

May reap fresh vigor from the leagues of old.

STAUFFACHER.

Hear, then, what aged herdsmen tell. There dwelt

A mighty people in the land that lies

Back to the north. The scourge of famine came;

And in this strait 'twas publicly resolved,

That each tenth man, on whom the lot might fall

Should leave the country. They obeyed—and forth,

With loud lamentings, men and women went,

A mighty host; and to the south moved on,

Cutting their way through Germany by the sword,

Until they gained that pine-clad hills of ours;

Nor stopped they ever on their forward course,

Till at the shaggy dell they halted, where

The Mueta flows through its luxuriant meads.

No trace of human creature met their eye,

Save one poor hut upon the desert shore,

Where dwelt a lonely man, and kept the ferry.

A tempest raged—the lake rose mountains high

And barred their further progress. Thereupon

They viewed the country; found it rich in wood,

Discovered goodly springs, and felt as they

Were in their own dear native land once more.

Then they resolved to settle on the spot;

Erected there the ancient town of Schwytz;

And many a day of toil had they to clear

The tangled brake and forest's spreading roots.

Meanwhile their numbers grew, the soil became

Unequal to sustain them, and they crossed

To the black mountain, far as Weissland, where,

Concealed behind eternal walls of ice,

Another people speak another tongue.

They built the village Stanz, beside the Kernwald

The village Altdorf, in the vale of Reuss;

Yet, ever mindful of their parent stem,

The men of Schwytz, from all the stranger race,

That since that time have settled in the land,

Each other recognize. Their hearts still know,

And beat fraternally to kindred blood.

[Extends his hand right and left.

MAUER.

Ay, we are all one heart, one blood, one race!

ALL (joining hands).

We are one people, and will act as one.

STAUFFACHER.

The nations round us bear a foreign yoke;

For they have yielded to the conqueror.

Nay, even within our frontiers may be found

Some that owe villein service to a lord,

A race of bonded serfs from sire to son.

But we, the genuine race of ancient Swiss,

Have kept our freedom from the first till now,

Never to princes have we bowed the knee;

Freely we sought protection of the empire.

ROSSELMANN.

Freely we sought it—freely it was given.

'Tis so set down in Emperor Frederick's charter.

STAUFFACHER.

For the most free have still some feudal lord.

There must be still a chief, a judge supreme,

To whom appeal may lie in case of strife.

And therefore was it that our sires allowed

For what they had recovered from the waste,

This honor to the emperor, the lord

Of all the German and Italian soil;

And, like the other freemen of his realm,

Engaged to aid him with their swords in war;

And this alone should be the freeman's duty,

To guard the empire that keeps guard for him.

MELCHTHAL.

He's but a slave that would acknowledge more.

STAUFFACHER.

They followed, when the Heribann 17 went forth,

The imperial standard, and they fought its battles!

To Italy they marched in arms, to place

The Caesars' crown upon the emperor's head.

But still at home they ruled themselves in peace,

By their own laws and ancient usages.

The emperor's only right was to adjudge

The penalty of death; he therefore named

Some mighty noble as his delegate,

That had no stake or interest in the land.

He was called in, when doom was to be passed,

And, in the face of day, pronounced decree,

Clear and distinctly, fearing no man's hate.

What traces here, that we are bondsmen? Speak,

If there be any can gainsay my words!

HOFE.

No! You have spoken but the simple truth;

We never stooped beneath a tyrant's yoke.

STAUFFACHER.

Even to the emperor we refused obedience,

When he gave judgment in the church's favor;

For when the Abbey of Einsiedlen claimed

The Alp our fathers and ourselves had grazed,

And showed an ancient charter, which bestowed

The land on them as being ownerless—

For our existence there had been concealed—

What was our answer? This: "The grant is void,

No emperor can bestow what is our own:

And if the empire shall deny us justice,

We can, within our mountains, right ourselves!"

Thus spake our fathers! And shall we endure

The shame and infamy of this new yoke,

And from the vassal brook what never king

Dared in the fulness of his power attempt?

This soil we have created for ourselves,

By the hard labor of our hands; we've changed

The giant forest, that was erst the haunt

Of savage bears, into a home for man;

Extirpated the dragon's brood, that wont

To rise, distent with venom, from the swamps;

Rent the thick misty canopy that hung

Its blighting vapors on the dreary waste;

Blasted the solid rock; o'er the abyss

Thrown the firm bridge for the wayfaring man

By the possession of a thousand years

The soil is ours. And shall an alien lord,

Himself a vassal, dare to venture here,

On our own hearths insult us,—and attempt

To forge the chains of bondage for our hands,

And do us shame on our own proper soil?

Is there no help against such wrong as this?

[Great sensation among the people.

Yes! there's a limit to the despot's power!

When the oppressed looks round in vain for justice,

When his sore burden may no more be borne,

With fearless heart he makes appeal to Heaven,

And thence brings down his everlasting rights,