Project Gutenberg's Fiesco or, The Genoese Conspiracy, by Friedrich Schiller

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Fiesco or, The Genoese Conspiracy

A Tragedy

Author: Friedrich Schiller

Release Date: October 25, 2006 [EBook #6783]

Last Updated: July 20, 2014

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK FIESCO OR, THE GENOESE CONSPIRACY ***

Produced by Tapio Riikonen and David Widger

The chief sources from which I have drawn the history of this conspiracy are Cardinal de Retz's Conjuration du Comte Jean Louis de Fiesque, the Histoire des Genes, and the third volume of Robertson's History of Charles the Fifth.

The liberties which I have taken with the historical facts will be excused, if I have succeeded in my attempt; and, if not, it is better that my failure should appear in the effusions of fancy, than in the delineation of truth. Some deviation from the real catastrophe of the conspiracy (according to which the count actually perished [A] when his schemes were nearly ripe for execution) was rendered necessary by the nature of the drama, which does not allow the interposition either of chance or of a particular Providence. It would be matter of surprise to me that this subject has never been adopted by any tragic writer, did not the circumstances of its conclusion, so unfit for dramatic representation, afford a sufficient reason for such neglect. Beings of a superior nature may discriminate the finest links of that chain which connects an individual action with the system of the universe, and may, perhaps, behold them extended to the utmost limits of time, past and future; but man seldom sees more than the simple facts, divested of their various relations of cause and effect. The writer, therefore, must adapt his performance to the short-sightedness of human nature, which he would enlighten; and not to the penetration of Omniscience, from which all intelligence is derived.

In my Tragedy of the Robbers it was my object to delineate the victim of an extravagant sensibility; here I endeavor to paint the reverse; a victim of art and intrigue. But, however strongly marked in the page of history the unfortunate project of Fiesco may appear, on the stage it may prove less interesting. If it be true that sensibility alone awakens sensibility, we may conclude that the political hero is the less calculated for dramatic representation, in proportion as it becomes necessary to lay aside the feelings of a man in order to become a political hero.

It was, therefore, impossible for me to breathe into my fable that glowing life which animates the pure productions of poetical inspiration; but, in order to render the cold and sterile actions of the politician capable of affecting the human heart, I was obliged to seek a clue to those actions in the human heart itself. I was obliged to blend together the man and the politician, and to draw from the refined intrigues of state situations interesting to humanity. The relations which I bear to society are such as unfold to me more of the heart than of the cabinet; and, perhaps, this very political defect may have become a poetical excellence.

[A] Fiesco, after having succeeded in the chief objects of his undertaking, happened to fall into the sea whilst hastening to quell some disturbances on board of a vessel in the harbor; the weight of his armor rendered his struggles ineffectual, and he perished. The deviation from history in the tragedy might have been carried farther, and would perhaps have rendered it more suitable to dramatic representation.—Translation.

ANDREAS DORIA, Duke of Genoa, a venerable old man, eighty years of age, retaining the traces of a high spirit: the chief features in this character are dignity and a rigid brevity in command.

GIANETTINO DORIA, nephew of the former, and pretender to the ducal power, twenty-six years of age, rough and forbidding in his address, deportment, and manners, with a vulgar pride and disgusting features.

FIESCO, Count of Lavagna, chief of the conspiracy, a tall, handsome young man, twenty-three years of age; his character is that of dignified pride and majestic affability, with courtly complaisance and deceitfulness.

VERRINA, a determined republican, sixty years of age; grave, austere, and inflexible: a marked character.

BOURGOGNINO, a conspirator, a youth of twenty; frank and high-spirited, proud, hasty, and undisguised.

CALCAGNO, a conspirator, a worn-out debauchee of thirty; insinuating and enterprising.

SACCO, a conspirator, forty-five years of age, with no distinguishing trait of character.

LOMELLINO, in the confidence of the pretender, a haggard courtier.

ZENTURIONE, | ZIBO, | Malcontents. ASSERATO, |

ROMANO, a painter, frank and simple, with the pride of genius.

MULEY HASSAN, a Moor of Tunis, an abandoned character, with a physiognomy displaying an original mixture of rascality and humor.

A GERMAN of the ducal body-guard, of an honest simplicity, and steady bravery.

THREE SEDITIOUS CITIZENS.

LEONORA, the wife of Fiesco, eighteen years of age, of great sensibility; her appearance pale and slender, engaging, but not dazzling; her countenance marked with melancholy; her dress black.

JULIA, Countess dowager Imperiali, sister of the younger Doria, aged twenty-five; a proud coquette, in person tall and full, her beauty spoiled by affectation, with a sarcastic maliciousness in her countenance; her dress black.

BERTHA, daughter of Verrina, an innocent girl.

ROSA, | Maids of Leonora. ARABELLA, |

Several Nobles, Citizens, Germans, Soldiers, Thieves.

(SCENE—Genoa. TIME—the year 1547.)

SCENE I.

A Saloon in FIESCO'S House. The distant sound of dancing and music is heard.

LEONORA, masked, and attended by ROSA and ARABELLA, enters hastily.

LEONORA (tears off her mask). No more! Not another word! 'Tis as clear as day! (Throwing herself in a chair.) This quite overcomes me——

ARABELLA. My lady!

LEONORA (rising.) What, before my eyes! with a notorious coquette! In presence of the whole nobility of Genoa! (strongly affected.)—Rosa! Arabella! and before my weeping eyes!

ROSA. Look upon it only as what it really was—a piece of gallantry. It was nothing more.

LEONORA. Gallantry! What! Their busy interchange of glances—the anxious watching of her every motion—the long and eager kiss upon her naked arm, impressed with a fervor that left in crimson glow the very traces of his lips! Ha! and the transport that enwrapped his soul, when, with fixed eyes, he sat like painted ecstacy, as if the world around him had dissolved, and naught remained in the eternal void but he and Julia. Gallantry? Poor thing! Thou hast never loved. Think not that thou canst teach me to distinguish gallantry from love!

ROSA. No matter, Signora! A husband lost is as good as ten lovers gained.

LEONORA. Lost? Is then one little intermission of the heart's pulsations a proof that I have lost Fiesco? Go, malicious slanderer! Come no more into my presence! 'Twas an innocent frolic—perhaps a mere piece of gallantry. Say, my gentle Arabella, was it not so?

ARABELLA. Most certainly! There can be no doubt of it!

LEONORA (in a reverie). But does she then feel herself sole mistress of his heart? Does her name lurk in his every thought?—meet him in every phase of nature? Can it be? Whither will these thoughts lead me? Is this beautiful and majestic world to him but as one precious diamond, on which her image—her image alone—is engraved? That he should love her? —love Julia! Oh! Your arm—support me, Arabella! (A pause; music is again heard.)

LEONORA (starting). Hark! Was not that Fiesco's voice, which from the tumult penetrated even hither? Can he laugh while his Leonora weeps in solitude? Oh, no, my child, it was the coarse, loud voice of Gianettino.

ARABELLA. It was, Signora—but let us retire to another apartment.

LEONORA. You change color, Arabella—you are false. In your looks, in the looks of all the inhabitants of Genoa, I read a something—a something which—(hiding her face)—oh, certainly these Genoese know more than should reach a wife's ear.

ROSA. Oh, jealousy! thou magnifier of trifles!

LEONORA (with melancholy enthusiasm). When he was still Fiesco; when in the orange-grove, where we damsels walked, I saw him—a blooming Apollo, blending the manly beauty of Antinous! Such was his noble and majestic deportment, as if the illustrious state of Genoa rested alone upon his youthful shoulders. Our eyes stole trembling glances at him, and shrunk back, as if with conscious guilt, whene'er they encountered the lightning of his looks. Ah, Arabella, how we devoured those looks! with what anxious envy did every one count those directed to her companions! They fell among us like the golden apple of discord—tender eyes burned fiercely—soft bosoms beat tumultuously—jealousy burst asunder all our bonds of friendship——

ARABELLA. I remember it well. All Genoa's female hearts were in rebellious ferment for so enviable a prize!

LEONORA (in rapture). And now to call him mine! Giddy, wondrous fortune!—to call the pride of Genoa mine!—he who from the chisel of the exhaustless artist, Nature, sprang forth all-perfect, combining every greatness of his sex in the most perfect union. Hear me, damsels! I can no longer conceal it—hear me! I confide to you something (mysteriously)—a thought!—when I stood at the altar with Fiesco,—when his hand lay in mine,—a thought, too daring for woman, rushed across me. "This Fiesco, whose hand now lies in thine—thy Fiesco"—but hush! let no man hear us boast how far he excels all others of his sex. "This, thy Fiesco"—ah, could you but share my feelings!—"will free Genoa from its tyrants!"

ARABELLA (astonished). And could this dream haunt a woman's mind even at the nuptial shrine?

LEONORA. Yes, my Arabella,—well mayest thou be astonished—to the bride it came, even in the joy of the bridal hour (more animated). I am a woman, but I feel the nobleness of my blood. I cannot bear to see these proud Dorias thus overtop our family. The good old Andreas—it is a pleasure to esteem him. He may indeed, unenvied, bear the ducal dignity; but Gianettino is his nephew—his heir—and Gianettino has a proud and wicked heart. Genoa trembles before him, and Fiesco (much affected)— Fiesco—weep with me, damsels!—loves his sister.

ARABELLA. Alas, my wretched mistress!

LEONORA. Go now, and see this demi-god of the Genoese—amid the shameless circles of debauchery and lust! hear the vile jests and wanton ribaldry with which he entertains his base companions! That is Fiesco! Ah, damsels, not only has Genoa lost its hero, but I have lost my husband!

ROSA. Speak lower! some one is coming through the gallery.

LEONORA (alarmed). Ha! 'Tis Fiesco—let us hasten away—the sight of me might for a moment interrupt his happiness. (She hastens into a side apartment; the maids follow.)

SCENE II

GIANETTINO DORIA, masked, in a green cloak, and the MOOR, enter in conversation.

GIANETTINO. Thou hast understood me!

MOOR. Well——

GIANETTINO. The white mask——

MOOR. Well——

GIANETTINO. I say, the white mask——

MOOR. Well—well—well——

GIANETTINO. Dost thou mark me? Thou canst only fail here! (pointing to his heart).

MOOR. Give yourself no concern.

GIANETTINO. And be sure to strike home——

MOOR. He shall have enough.

GIANETTINO (maliciously). That the poor count may not have long to suffer.

MOOR. With your leave, sir, a word—at what weight do you estimate his head?

GIANETTINO. What weight? A hundred sequins——

MOOR (blowing through his fingers). Poh! Light as a feather!

GIANETTINO. What art thou muttering?

MOOR. I was saying—it is light work.

GIANETTINO. That is thy concern. He is the very loadstone of sedition. Mark me, sirrah! let thy blow be sure.

MOOR. But, sir,—I must fly to Venice immediately after the deed.

GIANETTINO. Then take my thanks beforehand. (He throws him a bank-note.) In three days at farthest he must be cold.

[Exit.

MOOR (picking up the note). Well, this really is what I call credit to trust—the simple word of such a rogue as I am!

[Exit.

SCENE III.

CALCAGNO, behind him SACCO, both in black cloaks.

CALCAGNO. I perceive thou watchest all my steps.

SACCO. And I observe thou wouldst conceal them from me. Attend, Calcagno! For some weeks past I have remarked the workings of thy countenance. They bespeak more than concerns the interests of our country. Brother, I should think that we might mutually exchange our confidence without loss on either side. What sayest thou? Wilt thou be sincere?

CALCAGNO. So truly, that thou shalt not need to dive into the recesses of my soul; my heart shall fly half-way to meet thee on my tongue—I love the Countess of Fiesco.

SACCO (starts back with astonishment). That, at least, I should not have discovered had I made all possibilities pass in review before me. My wits are racked to comprehend thy choice, but I must have lost them altogether if thou succeed.

CALCAGNO. They say she is a pattern of the strictest virtue.

SACCO. They lie. She is the whole volume on that insipid text. Calcagno, thou must choose one or the other—either to give up thy heart or thy profession.

CALCAGNO. The Count is faithless to her; and of all the arts that may seduce a woman the subtlest is jealousy. A plot against the Dorias will at the same time occupy the Count, and give me easy access to his house. Thus, while the shepherd guards against the wolf, the fox shall make havoc of the poultry.

SACCO. Incomparable brother, receive my thanks! A blush is now superfluous, and I can tell thee openly what just now I was ashamed even to think. I am a beggar if the government be not soon overturned.

CALCAGNO. What, are thy debts so great?

SACCO. So immense that even one-tenth of them would more than swallow ten times my income. A convulsion of the state will give me breath; and if it do not cancel all my debts, at least 'twill stop the mouths of bawling creditors.

CALCAGNO. I understand thee; and if then, perchance, Genoa should be freed, Sacco will be hailed his country's savior. Let no one trick out to me the threadbare tale of honesty, if the fate of empires hang on the bankruptcy of a prodigal and the lust of a debauchee. By heaven, Sacco, I admire the wise design of Providence, that in us would heal the corruptions in the heart of the state by the vile ulcers on its limbs. Is thy design unfolded to Verrina?

SACCO. As far as it can be unfolded to a patriot. Thou knowest his iron integrity, which ever tends to that one point, his country. His hawk-like eye is now fixed on Fiesco, and he has half-conceived a hope of thee to join the bold conspiracy.

CALCAGNO. Oh, he has an excellent nose! Come, let us seek him, and fan the flame of liberty in his breast by our accordant spirit.

[Exeunt.

SCENE IV.

JULIA, agitated with anger, and FIESCO, in a white mask, following her.

JULIA. Servants! footmen!

FIESCO. Countess, whither are you going? What do you intend?

JULIA. Nothing—nothing at all. (To the servants, who enter and immediately retire.) Let my carriage draw up——

FIESCO. Pardon me, it must not. You are offended.

JULIA. Oh, by no means. Away—you tear my dress to pieces. Offended. Who is here that can offend me? Go, pray go.

FIESCO (upon one knee). Not till you tell me what impertinent——

JULIA (stands still in a haughty attitude). Fine! Fine! Admirable! Oh, that the Countess of Lavagna might be called to view this charming scene! How, Count, is this like a husband? This posture would better suit the chamber of your wife when she turns over the journal of your caresses and finds a void in the account. Rise, sir, and seek those to whom your overtures will prove more acceptable. Rise—unless you think your gallantries will atone for your wife's impertinence.

FIESCO (jumping up). Impertinence! To you?

JULIA. To break up! To push away her chair! To turn her back upon the table—that table, Count, where I was sitting——

FIESCO. 'Tis inexcusable.

JULIA. And is that all? Out upon the jade! Am I, then, to blame because the Count makes use of his eyes? (Smilingly admiring herself.)

FIESCO. 'Tis the fault of your beauty, madam, that keeps them in such sweet slavery.

JULIA. Away with compliment where honor is concerned. Count, I insist on satisfaction. Where shall I find it, in you, or in my uncle's vengeance?

FIESCO. Find it in the arms of love—of love that would repair the offence of jealousy.

JULIA. Jealousy! Jealousy! Poor thing! What would she wish for? (Admiring herself in the glass.) Could she desire a higher compliment than were I to declare her taste my own? (Haughtily.) Doria and Fiesco! Would not the Countess of Lavagna have reason to feel honored if Doria's niece deigned to envy her choice? (In a friendly tone, offering the Count her hand to kiss.) I merely assume the possibility of such a case, Count.

FIESCO (with animation). Cruel Countess! Thus to torment me. I know, divine Julia, that respect is all I ought to feel for you. My reason bids me bend a subject's knee before the race of Doria; but my heart adores the beauteous Julia. My love is criminal, but 'tis also heroic, and dares o'erleap the boundaries of rank, and soar towards the dazzling sun of majesty.

JULIA. A great and courtly falsehood, paraded upon stilts! While his tongue deifies me, his heart beats beneath the picture of another.

FIESCO. Rather say it beats indignantly against it, and would shake off the odious burden. (Taking the picture of LEONORA, which is suspended by a sky-blue ribbon from his breast, and delivering it to JULIA.) Place your own image on that altar and you will instantly annihilate this idol.

JULIA (pleased, puts by the picture hastily). A great sacrifice, by mine honor, and which deserves my thanks. (Hangs her own picture about his neck.) So, my slave, henceforth bear your badge of service.

[Exit.

FIESCO (with transport). Julia loves me! Julia! I envy not even the gods. (Exulting.) Let this night be a jubilee. Joy shall attain its summit. Ho! within there! (Servants come running in.) Let the floors swim with Cyprian nectar, soft strains of music rouse midnight from her leaden slumber, and a thousand burning lamps eclipse the morning sun. Pleasure shall reign supreme, and the Bacchanal dance so wildly beat the ground that the dark kingdom of the shades below shall tremble at the uproar!

[Exit hastily. A noisy allegro, during which the back scene opens, and discovers a grand illuminated saloon, many masks—dancing. At the side, drinking and playing tables, surrounded with company.

SCENE V.

GIANETTINO, almost intoxicated, LOMELLINO, ZIBO, ZENTURIONE, VERRINA, CALCAGNO, all masked. Several other nobles and ladies.

GIANETTINO (boisterously). Bravo! Bravo! These wines glide down charmingly. The dancers perform a merveille. Go, one of you, and publish it throughout Genoa that I am in good humor, and that every one may enjoy himself. By my ruling star this shall be marked as a red-letter day in the calendar, and underneath be written,—"This day was Prince Doria merry." (The guests lift their glasses to their mouths. A general toast of "The Republic." Sound of trumpets.) The Republic? (Throwing his glass violently on the ground.) There lie its fragments. (Three black masks suddenly rise and collect about GIANETTINO.)

LOMELLINO (supporting GIANETTINO on his arm). My lord, you lately spoke of a young girl whom you saw in the church of St. Lorenzo.

GIANETTINO. I did, my lad! and I must make her acquaintance.

LOMELLINO. That I can manage for your grace.

GIANETTINO (with vehemence). Can you? Can you? Lomellino, you were a candidate for the procuratorship. You shall have it.

LOMELLINO. Gracious prince, it is the second dignity in the state; more than threescore noblemen seek it, and all of them more wealthy and honorable than your grace's humble servant.

GIANETTINO (indignantly). By the name of Doria! You shall be procurator. (The three masks come forward). What talk you of nobility in Genoa? Let them all throw their ancestry and honors into the scale, one hair from the white beard of my old uncle will make it kick the beam. It is my will that you be procurator, and that is tantamount to the votes of the whole senate.

LOMELLINO (in a low voice). The damsel is the only daughter of one Verrina.

GIANETTINO. The girl is pretty, and, in spite of all the devils in hell, I must possess her.

LOMELLINO. What, my lord! the only child of the most obstinate of our republicans?

GIANETTINO. To hell with your republicans! Shall my passion be thwarted by the anger of a vassal? 'Tis as vain as to expect the tower should fall when the boys pelt it with mussel-shells. (The three black masks step nearer, with great emotion.) What! Has the Duke Andreas gained his scars in battle for their wives and children, only that his nephew should court the favor of these vagabond republicans! By the name of Doria they shall swallow this fancy of mine, or I will plant a gallows over the bones of my uncle, on which their Genoese liberty shall kick itself to death. (The three masks step back in disgust.)

LOMELLINO. The damsel is at this moment alone. Her father is here, and one of those three masks.

GIANETTINO. Excellent! Bring me instantly to her.

LOMELLINO. But you will seek in her a mistress, and find a prude.

GIANETTINO. Force is the best rhetoric. Lead me to her. Would I could see that republican dog that durst stand in the way of the bear Doria. (Going, meets FIESCO at the door.) Where is the Countess?

SCENE VI.

FIESCO and the former.

FIESCO. I have handed her to her carriage. (Takes GIANETTINO'S hand, and presses it to his breast.) Prince, I am now doubly your slave. To you I bow, as sovereign of Genoa—to your lovely sister, as mistress of my heart.

LOMELLINO. Fiesco has become a mere votary of pleasure. The great world has lost much in you.

FIESCO. But Fiesco has lost nothing in giving up the world. To live is to dream, and to dream pleasantly is to be wise. Can this be done more certainly amid the thunders of a throne, where the wheels of government creak incessantly upon the tortured ear, than on the heaving bosom of an enamored woman? Let Gianettino rule over Genoa; Fiesco shall devote himself to love.

GIANETTINO. Away, Lomellino! It is near midnight. The time draws near —Lavagna, we thank thee for thy entertainment—I have been satisfied.

FIESCO. That, prince, is all that I can wish.

GIANETTINO. Then good-night! To-morrow we have a party at the palace, and Fiesco is invited. Come, procurator!

FIESCO. Ho! Lights there! Music!

GIANETTINO (haughtily, rushing through the three masks). Make way there for Doria!

ONE OF THE THREE MASKS (murmuring indignantly). Make way? In hell! Never in Genoa!

THE GUESTS (in motion). The prince is going. Good night, Lavagna! (They depart.)

SCENE VII.

The THREE BLACK MASKS and FIESCO. (A pause.)

FIESCO. I perceive some guests here who do not share the pleasure of the feast.

MASKS (murmuring to each other with indignation). No! Not one of us.

FIESCO (courteously). Is it possible that my attention should have been wanting to any one of my guests? Quick, servants! Let the music be renewed, and fill the goblets to the brim. I would not that my friends should find the time hang heavy. Will you permit me to amuse you with fireworks. Would you choose to see the frolics of my harlequin? Perhaps you would be pleased to join the ladies. Or shall we sit down to faro, and pass the time in play?

A MASK. We are accustomed to spend it in action.

FIESCO. A manly answer—such as bespeaks Verrina.

VERRINA (unmasking). Fiesco is quicker to discover his friends beneath their masks than they to discover him beneath his.

FIESCO. I understand you not. But what means that crape of mourning around your arm? Can death have robbed Verrina of a friend, and Fiesco not know the loss?

VERRINA. Mournful tales ill suit Fiesco's joyful feasts.

FIESCO. But if a friend—(pressing his hand warmly.) Friend of my soul! For whom must we both mourn?

VRRRINA. Both! both! Oh, 'tis but too true we both should mourn—yet not all sons lament their mother.

FIESCO. 'Tis long since your mother was mingled with the dust.

VERRINA (with an earnest look). I do remember me that Fiesco once called me brother, because we both were sons of the same country!

FIESCO (jocosely). Oh, is it only that? You meant then but to jest? The mourning dress is worn for Genoa! True, she lies indeed in her last agonies. The thought is new and singular. Our cousin begins to be a wit.

VERRINA. Fiesco! I spoke most seriously.

FIESCO. Certainly—certainly. A jest loses its point when he who makes it is the first to laugh. But you! You looked like a mute at a funeral. Who could have thought that the austere Verrina should in his old age become such a wag!

SACCO. Come, Verrina. He never will be ours.

FIESCO. Be merry, brother. Let us act the part of the cunning heir, who walks in the funeral procession with loud lamentations, laughing to himself the while, under the cover of his handkerchief. 'Tis true we may be troubled with a harsh step-mother. Be it so—we will let her scold, and follow our own pleasures.

VERRINA (with great emotion). Heaven and earth! Shall we then do nothing? What is to become of you, Fiesco? Where am I to seek that determined enemy of tyrants? There was a time when but to see a crown would have been torture to you. Oh, fallen son of the republic! By heaven, if time could so debase my soul I would spurn immortality.

FIESCO. O rigid censor! Let Doria put Genoa in his pocket, or barter it with the robbers of Tunis. Why should it trouble us? We will drown ourselves in floods of Cyprian wine, and revel it in the sweet caresses of our fair ones.

VERRINA (looking at him with earnestness). Are these indeed your serious thoughts?

FIESCO. Why should they not be, my friend? Think you 'tis a pleasure to be the foot of that many-legged monster, a republic? No—thanks be to him who gives it wings, and deprives the feet of their functions! Let Gianettino be the duke, affairs of state shall ne'er lie heavy on our heads.

VERRINA. Fiesco! Is that truly and seriously your meaning?

FIESCO. Andreas adopts his nephew as a son, and makes him heir to his estates; what madman will dispute with him the inheritance of his power?

VERRINA (with the utmost indignation). Away, then, Genoese! (Leaves FIESCO hastily, the rest follow.)

FIESCO. Verrina! Verrina! Oh, this republican is as hard as steel!

SCENE VIII.

FIESCO. A MASK entering.

MASK. Have you a minute or two to spare, Lavagna?

FIESCO (in an obliging manner). An hour if you request it.

MASK. Then condescend to walk into the fields with me.

FIESCO. It wants but ten minutes of midnight.

MASK. Walk with me, Count, I pray.

FIESCO. I will order my carriage.

MASK. That is useless—I shall send one horse: we want no more, for only one of us, I hope, will return.

FIESCO (with surprise). What say you?

MASK. A bloody answer will be demanded of you, touching a certain tear.

FIESCO. What tear?

MASK. A tear shed by the Countess of Lavagna. I am acquainted with that lady, and demand to know how she has merited to be sacrificed to a worthless woman?

FIESCO. I understand you now; but let me ask who 'tis that offers so strange a challenge?

MASK. It is the same that once adored the lady Zibo, and yielded her to Fiesco.

FIESCO. Scipio Bourgognino!

BOURGOGNINO (unmasking). And who now stands here to vindicate his honor, that yielded to a rival base enough to tyrannize over innocence.

FIESCO (embraces him with ardor). Noble youth! thanks to the sufferings of my consort, which have drawn forth the manly feelings of your soul; I admire your generous indignation—but I refuse your challenge.

BOURGOGNINO (stepping back). Does Fiesco tremble to encounter the first efforts of my sword?

FIESCO. No, Bourgognino! against a nation's power combined I would boldly venture, but not against you. The fire of your valor is endeared to me by a most lovely object—the will deserves a laurel, but the deed would be childish.

BOURGOGNINO (with emotion). Childish, Count! women can only weep at injuries. 'Tis for men to revenge them.

FIESCO. Uncommonly well said—but fight I will not.

BOURGOGNINO (turning upon him contemptuously). Count, I shall despise you.

FIESCO (with animation). By heaven, youth, that thou shalt never do—not even if virtue fall in value, shall I become a bankrupt. (Taking him by the hand, with a look of earnestness.) Did you ever feel for me—what shall I say—respect?

BOURGOGNINO. Had I not thought you were the first of men I should not have yielded to you.

FIESCO. Then, my friend, be not so forward to despise a man who once could merit your respect. It is not for the eye of the youthful artist to comprehend at once the master's vast design. Retire, Bourgognino, and take time to weigh the motives of Fiesco's conduct!

[Exit BOURGOGNINO, in silence.

Go! noble youth! if spirits such as thine break out in flames in thy country's cause, let the Dorias see that they stand fast!

SCENE IX.

FIESCO.—The MOOR entering with an appearance of timidity, and looking round cautiously.

FIESCO (fixing his eye on him sharply). What wouldst thou here? Who art thou?

MOOR (as above). A slave of the republic.

FIESCO (keeping his eye sharply upon him). Slavery is a wretched craft. What dost thou seek?

MOOR. Sir, I am an honest man.

FIESCO. Wear then that label on thy visage, it will not be superfluous— but what wouldst thou have?

MOOR (approaching him, FIESCO draws back). Sir, I am no villain.

FIESCO. 'Tis well thou hast told me that—and yet—'tis not well either (impatiently). What dost thou seek?

MOOR (still approaching). Are you the Count Lavagna?

FIESCO (haughtily). The blind in Genoa know my steps—what wouldst thou with the Count?

MOOR (close to him). Be on your guard, Lavagna!

FIESCO (passing hastily to the other side). That, indeed, I am.

MOOR (again approaching). Evil designs are formed against you, Count.

FIESCO (retreating). That I perceive.

MOOR. Beware of Doria!

FIESCO (approaching him with an air of confidence). Perhaps my suspicions have wronged thee, my friend—Doria is indeed the name I dread.

MOOR. Avoid the man, then. Can you read?

FIESCO. A curious question! Thou hast known, it seems, many of our cavaliers. What writing hast thou?

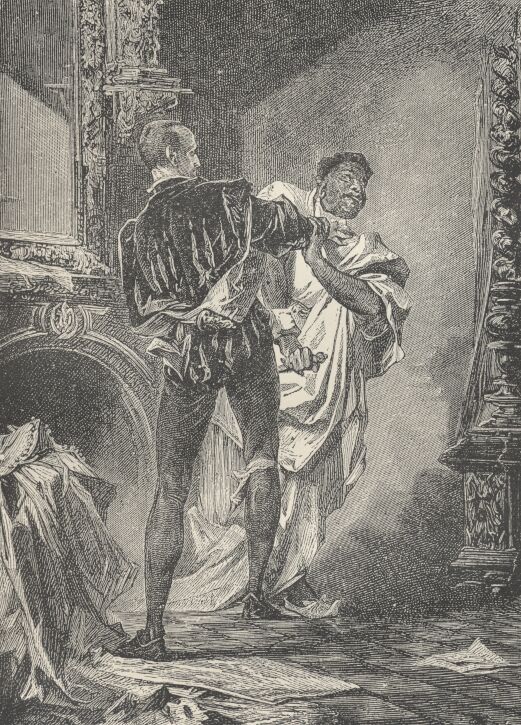

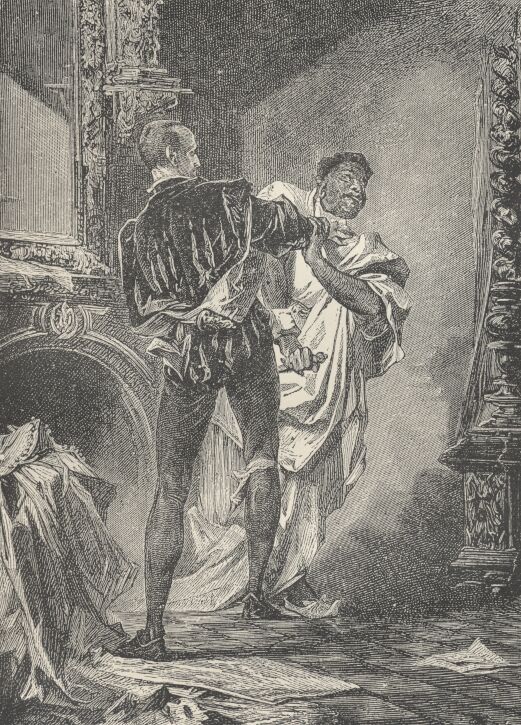

MOOR. Your name is amongst other condemned sinners. (Presents a paper, and draws close to FIESCO, who is standing before a looking-glass and glancing over the paper—the MOOR steals round him, draws a dagger, and is going to stab.)

FIESCO (turning round dexterously, and seizing the MOOR'S arm.) Stop, scoundrel! (Wrests the dagger from him.)

MOOR (stamps in a frantic manner). Damnation! Your pardon—sire!

FIESCO (seizing him, calls with a loud voice). Stephano! Drullo! Antonio! (holding the MOOR by the throat.) Stay, my friend!—what hellish villany! (Servants enter.) Stay, and answer—thou hast performed thy task like a bungler. Who pays thy wages?

MOOR (after several fruitless attempts to escape). You cannot hang me higher than the gallows are——

FIESCO. No—be comforted—not on the horns of the moon, but higher than ever yet were gallows—yet hold! Thy scheme was too politic to be of thy own contrivance speak, fellow! who hired thee?

MOOR. Think me a rascal, sir, but not a fool.

FIESCO. What, is the scoundrel proud? Speak, sirrah! Who hired thee?

MOOR (aside). Shall I alone be called a fool? Who hired me? 'Twas but a hundred miserable sequins. Who hired me, did you ask? Prince Gianettino.

FIESCO (walking about in a passion). A hundred sequins? And is that all the value set upon Fiesco's head? Shame on thee, Prince of Genoa! Here, fellow (taking money from an escritoire), are a thousand for thee. Tell thy master he is a niggardly assassin. (MOOR looks at him with astonishment.) What dost thou gaze at? (MOOR takes up the money—lays it down—takes it up again, and looks at FIESCO with increased astonishment). What dost thou mean?

MOOR (throwing the money resolutely upon the table). Sir, that money I have not earned—I deserve it not.

FIESCO. Blockhead, thou hast deserved the gallows; but the offended elephant tramples on men not on worms. Were thy life worth but two words I would have thee hanged.

MOOR (bowing with an air of pleasure at his escape). Sir, you are too good——

FIESCO. Not towards thee! God forbid! No. I am amused to think my humor can make or unmake such a villain as thou, therefore dost thou go scot-free—understand me aright—I take thy failure as an omen of my future greatness—'tis this thought that renders me indulgent, and preserves thy life.

MOOR (in a tone of confidence). Count, your hand! honor for honor. If any man in this country has a throat too much—command me, and I'll cut it—gratis.

FIESCO. Obliging scoundrel! He would show his gratitude by cutting throats wholesale!

MOOR. Men like me, sir, receive no favor without acknowledgment. We know what honor is.

FIESCO. The honor of cut-throats?

MOOR. Which is, perhaps, more to be relied on than that of your men of character. They break their oaths made in the name of God. We keep ours pledged to the devil.

FIESCO. Thou art an amusing villain.

MOOR. I rejoice to meet your approbation. Try me; you will find in me a man who is a thorough master of his profession. Examine me; I can show my testimonials of villany from every guild of rogues—from the lowest to the highest.

FIESCO. Indeed! (seating himself.) There are laws and systems then even among thieves. What canst thou tell me of the lowest class?

MOOR. Oh, sir, they are petty villains, mere pick-pockets. They are a miserable set. Their trade never produces a man of genius; 'tis confined to the whip and workhouse—and at most can lead but to the gallows.

FIESCO. A charming prospect! I should like to hear something of a superior class.

MOOR. The next are spies and informers—tools of importance to the great, who from their secret information derive their own supposed omniscience. These villains insinuate themselves into the souls of men like leeches; they draw poison from the heart, and spit it forth against the very source from whence it came.

FIESCO. I understand thee—go on——

MOOR. Then come the conspirators, villains that deal in poison, and bravoes that rush upon their victims from some secret covert. Cowards they often are, but yet fellows that sell their souls to the devil as the fees of their apprenticeship. The hand of justice binds their limbs to the rack or plants their cunning heads on spikes—this is the third class.

FIESCO. But tell me! When comes thy own?

MOOR. Patience, my lord—that is the very point I'm coming to—I have already passed through all the stages that I mentioned: my genius soon soared above their limits. 'Twas but last night I performed my masterpiece in the third; this evening I attempted the fourth, and proved myself a bungler.

FIESCO. And how do you describe that class?

MOOR (with energy). They are men who seek their prey within four walls, cutting their way through every danger. They strike at once, and, by their first salute, save him whom they approach the trouble of returning thanks for a second. Between ourselves they are called the express couriers of hell: and when Beelzebub is hungry they want but a wink, and he gets his mutton warm.

FIESCO. Thou art an hardened villain—such a tool I want. Give me thy hand—thou shalt serve me.

MOOR. Jest or earnest?

FIESCO. In full earnest—and I'll pay thee yearly a 'thousand sequins.

MOOR. Done, Lavagna! I am yours. Away with common business—employ me in whate'er you will. I'll be your setter or your bloodhound—your fox, your viper—your pimp, or executioner. I'm prepared for all commissions —except honest ones; in those I am as stupid as a block.

FIESCO. Fear not! I would not set the wolf to guard the lamb. Go thou through Genoa to-morrow and sound the temper of the people. Narrowly inquire what they think of the government, and of the house of Doria— what of me, my debaucheries, and romantic passion. Flood their brains with wine, until the sentiments of the heart flow over. Here's money— lavish it among the manufacturers——

MOOR. Sir!

FIESCO. Be not afraid—no honesty is in the case. Go, collect what help thou canst. To-morrow I will hear thy report.

[Exit.

MOOR (following). Rely on me. It is now four o'clock in the morning, by eight to-morrow you shall hear as much news as twice seventy spies can furnish.

[Exit.

SCENE X.

An apartment in the house of VERRINA. BERTHA on a couch, supporting her head on her hand— VERRINA enters with a look of dejection.

BERTHA (starts up frightened). Heavens! He is here!

VERRINA (stops, looking at her with surprise). My daughter affrighted at her father!

BERTHA. Fly! fly! or let me fly! Father, your sight is dreadful to me!

VERRINA. Dreadful to my child!—my only child!

BERTHA (looking at him mournfully). Oh! you must seek another. I am no more your daughter.

VERRINA. What, does my tenderness distress you?

BERTHA. It weighs me down to the earth.

VERRINA. How, my daughter! do you receive me thus? Formerly, when I came home, my heart o'erburdened with sorrows, my Bertha came running towards me, and chased them away with her smiles. Come, embrace me, my daughter! Reclined upon thy glowing bosom, my heart, when chilled by the sufferings of my country, shall grow warm again. Oh, my child! this day I have closed my account with the joys of this world, and thou alone (sighing heavily) remainest to me.

BERTHA (casting a long and earnest look at him). Wretched father!

VERRINA (eagerly embracing her). Bertha! my only child! Bertha! my last remaining hope! The liberty of Genoa is lost—Fiesco is lost—and thou (pressing her more strongly, with a look of despair) mayest be dishonored!

BERTHA (tearing herself from him). Great God! You know, then——

VERRINA (trembling). What?

BERTHA. My virgin honor——

VERRINA (raging). What?

BERTHA. Last night——

VERRINA (furiously.) Speak! What!

BERTHA. Force. (Sinks down upon the side of the sofa.)

VERRINA (after a long pause, with a hollow voice). One word more, my daughter—thy last! Who was it?

BERTHA. Alas, what an angry deathlike paleness! Great God, support me! How his words falter! His whole frame trembles!

VERRINA. I cannot comprehend it. Tell me, my daughter—who?

BERTHA. Compose yourself, my best, my dearest father!

VERRINA (ready to faint). For God's sake—who?

BERTHA. A mask——

VERRINA (steps back, thoughtfully). No! That cannot be!—the thought is idle—(smiling to himself ). What a fool am I to think that all the poison of my life can flow but from one source! (Firmly addressing himself to BERTHA.) What was his stature, less than mine or taller?

BERTHA. Taller.

VERRINA (eagerly). His hair? Black, and curled?

BERTHA. As black as jet and curled?

VERRINA (retiring from her in great emotion). O God! my brain! my brain! His voice?

BERTHA. Was deep and harsh.

VERRINA (impetuously). What color was—No! I'll hear no more! 'His cloak! What color?

BERTHA. I think his cloak was green.

VERRINA (covering his face with his hands, falls on the couch). No more. This can be nothing but a dream!

BERTHA (wringing her hands). Merciful heaven! Is this my father?

VERRINA (after a pause, with a forced smile). Right! It serves thee right—coward Verrina! The villain broke into the sanctuary of the laws. This did not rouse thee. Then he violated the sanctuary of thy honor (starting up). Quick! Nicolo! Bring balls and powder—but stay—my sword were better. (To BERTHA.) Say thy prayers! Ah! what am I going to do?

BERTHA. Father, you make me tremble——

VERRINA. Come, sit by me, Bertha! (in a solemn manner.) Tell me, Bertha, what did that hoary-headed Roman, when his daughter—like you— how can I speak it! fell a prey to ignominy? Tell me, Bertha, what said Virginius to his dishonored daughter?

BERTHA (shuddering). I know not.

VERRINA. Foolish girl! He said nothing—but (rising hastily and snatching up a sword) he seized an instrument of death——

BERTHA (terrified, rushes into his arms). Great God! What would you do, my father?

VERRINA (throwing away the sword). No! There is still justice left in Genoa.

SCENE XI.

SACCO, CALCAGNO, the former.

CALCAGNO. Verrina, quick! prepare! to-day begins the election week of the republic. Let us early to the Senate House to choose the new senators. The streets are full of people, you will undoubtedly accompany us (ironically) to behold the triumph of our liberty.

SACCO (to CALCAGNO). But what do I see? A naked sword! Verrina staring wildly! Bertha in tears!

CALCAGNO. By heavens, it is so. Sacco! some strange event has happened here.

VERRINA (placing two chairs). Be seated.

SACCO. Your looks, Verrina, fill us with apprehension.

CALCAGNO. I never saw you thus before—Bertha is in tears, or your grief would have seemed to presage our country's ruin.

VERRINA. Ruin! Pray sit down. (They both seat themselves.)

CALCAGNO. My friend, I conjure you——

VERRINA. Listen to me.

CALCAGNO (to SACCO). I have sad misgivings.

VERRINA. Genoese! you both know the antiquity of my family. Your ancestors were vassals to my own. My forefathers fought the battles of the state, their wives were patterns of virtue. Honor was our sole inheritance, descending unspotted from the father to the son. Can any one deny it?

SACCO. No.

CALCAGNO. No one, by the God of heaven!

VERRINA. I am the last of my family. My wife has long been dead. This daughter is all she left me. You are witnesses, my friends, how I have brought her up. Can anyone accuse me of neglect?

CALCAGNO. No. Your daughter is a bright example to her sex.

VERRINA. I am old, my friends. On this one daughter all my hopes were placed. Should I lose her, my race becomes extinct. (After a pause, with a solemn voice). I have lost her. My family is dishonored.

SACCO and CALCAGNO. Forbid it, heaven! (BERTHA on the couch, appears much affected.)

VERRINA. No. Despair not, daughter! These men are just and brave. If they feel thy wrongs they will expiate them with blood. Be not astonished, friends! He who tramples upon Genoa may easily overcome a helpless female.

SACCO and CALCAGNO (starting up with emotion). Gianettino Doria!

BERTHA (with a shriek, seeing BOURGOGNINO enter). Cover me, walls, beneath your ruins! My Scipio!

SCENE XII.

BOURGOGNINO—the former.

BOURGOGNINO (with ardor). Rejoice, my love! I bring good tidings. Noble Verrina, my heaven now depends upon a word from you. I have long loved your daughter, but never dared to ask her hand, because my whole fortune was intrusted to the treacherous sea. My ships have just now reached the harbor laden with valuable cargoes. Now I am rich. Bestow your Bertha on me—I will make her happy. (BERTHA hides her face—a profound pause.)

VERRINA. What, youth! Wouldst thou mix thy heart's pure tide with a polluted stream?

BOURGOGNINO (clasps his hand to his sword, but suddenly draws it back). 'Twas her father said it.

VERRINA. No—every rascal in Italy will say it. Are you contented with the leavings of other men's repasts?

BOURGOGNINO. Old man, do not make me desperate.

CALCAGNO. Bourgognino! he speaks the truth.

BOURGOGNINO (enraged, rushing towards BERTHA). The truth? Has the girl then mocked me?

CALCAGNO. No! no! Bourgognino. The girl is spotless as an angel.

BOURGOGNINO (astonished). By my soul's happiness, I comprehend it not! Spotless, yet dishonored! They look in silence on each other. Some horrid crime hangs on their trembling tongues. I conjure you, friends, mock not thus my reason. Is she pure? Is she truly so? Who answers for her?

VERRINA. My child is guiltless.

BOURGOGNINO. What! Violence! (Snatches the sword from the ground.) Be all the sins of earth upon my bead if I avenge her not! Where is the spoiler?

VERRINA. Seek him in the plunderer of Genoa! (BOURGOGNINO struck with astonishment—VERRINA walks up and down the room in deep thought, then stops.) If rightly I can trace thy counsels, O eternal Providence! it is thy will to make my daughter the instrument of Genoa's deliverance. (Approaching her slowly, takes the mourning crape from his arm, and proceeds in a solemn manner.) Before the heart's blood of Doria shall wash away this foul stain from thy honor no beam of daylight shall shine upon these cheeks. Till then (throwing the crape over her) be blind! (A pause—the rest look upon him with silent astonishment; he continues solemnly, his hand upon BERTHA'S head.) Cursed be the air that shall breathe on thee! Cursed the sleep that shall refresh thee! Cursed every human step that shall come to sooth thy misery! Down, into the lowest vault beneath my house! There whine, and cry aloud! (pausing with inward horror.) Be thy life painful as the tortures of the writhing worm— agonizing as the stubborn conflict between existence and annihilation. This curse lie on thee till Gianettino shall have heaved forth his dying breath. If he escape his punishment, then mayest thou drag thy load of misery throughout the endless circle of eternity!

[A deep silence—horror is marked on the countenances of all present. VERRINA casts a scrutinizing look at each of them.

BOURGOGNINO. Inhuman father! What is it thou hast done? Why pour forth this horrible and monstrous curse against thy guiltless daughter?

VERRINA. Youth, thou say'st true!—it is most horrible. Now who among you will stand forth and prate still of patience and delay? My daughter's fate is linked with that of Genoa. I sacrifice the affections of a father to the duties of a citizen. Who among us is so much a coward as to hesitate in the salvation of his country, when this poor guiltless being must pay for his timidity with endless sufferings? By heavens, 'twas not a madman's speech! I have sworn an oath, and till Doria lie in the agonies of death I will show no mercy to my child. No—not though, like an executioner, I should invent unheard-of torments for her, or with my own hands rend her innocent frame piecemeal on the barbarous rack. You shudder—you stare at me with ghastly faces. Once more, Scipio—I keep her as a hostage for the tyrant's death. Upon this precious thread do I suspend thy duty, my own, and yours (to SACCO and CALCAGNO). The tyrant of Genoa falls, or Bertha must despair—I retract not.

BOURGOGNINO (throwing himself at BERTHA'S feet). He shall fall—shall fall a victim to Genoa. I will as surely sheathe this sword in Doria's heart as upon thy lips I will imprint the bridal kiss. (Rises.)

VERRINA. Ye couple, the first that ever owed their union to the Furies, join hands! Thou wilt sheathe thy sword in Doria's heart? Take her! she is thine!

CALCAGNO (kneeling). Here kneels another citizen of Genoa and lays his faithful sword before the feet of innocence. As surely may Calcagno find the way to heaven as this steel shall find its way to Gianettino's heart! (Rises.)

SACCO (kneeling). Last, but not less determined, Raffaelle Sacco kneels. If this bright steel unlock not the prison doors of Bertha, mayest thou, my Saviour, shut thine ear against my dying prayers! (Rises.)

VERRINA (with a calm look). Through me Genoa thanks you. Now go, my daughter; rejoice to be the mighty sacrifice for thy country!

BOURGOGNINO (embracing her as she is departing). Go! confide in God—and Bourgognino. The same day shall give freedom to Bertha and to Genoa.

[BERTHA retires.

SCENE XIII.

The former—without BERTHA.

CALCAGNO. Genoese, before we take another step, one word——

VERRINA. I guess what you would say.

CALCAGNO. Will four patriots alone be sufficient to destroy this mighty hydra? Shall we not stir up the people to rebellion, or draw the nobles in to join our party?

VERRINA. I understand you. Now hear my advice; I have long engaged a painter who has been exerting all his skill to paint the fall of Appius Claudius. Fiesco is an adorer of the arts, and soon warmed by ennobling scenes. We will send this picture to his house, and will be present when he contemplates it. Perhaps the sight may rouse his dormant spirit. Perhaps——

BOURGOGNINO. No more of him. Increase the danger, not the sharers in it. So valor bids. Long have I felt a something within my breast that nothing would appease. What 'twas now bursts upon me (springing up with enthusiasm); 'twas a tyrant!

[The scene closes.

SCENE I.—

An Ante-chamber in the Palace of FIESCO. LEONORA and ARABELLA.

ARABELLA. No, no, you were mistaken: your eyes were blinded by jealousy.

LEONORA. It was Julia to the life. Seek not to persuade me otherwise. My picture was suspended by a sky-blue ribbon: this was flame-colored. My doom is fixed irrevocably.

SCENE II.

The former and JULIA.

JULIA (entering in an affected manner). The Count offered me his palace to see the procession to the senate-house. The time will be tedious. You will entertain me, madam, while the chocolate is preparing.

[ARABELLA goes out, and returns soon afterwards.

LEONORA. Do you wish that I should invite company to meet you?

JULIA. Ridiculous! As if I should come hither in search of company. You will amuse me, madam (walking up and down, and admiring herself ), if you are able, madam. At any rate I shall lose nothing.

ARABELLA (sarcastically). Your splendid dress alone will be the loser. Only think how cruel it is to deprive the eager eyes of our young beaux of such a treat! Ah! and the glitter of your sparkling jewels on which it almost wounds the sight to look. Good heavens! You seem to have plundered the whole ocean of its pearls.

JULIA (before a glass). You are not accustomed to such things, miss! But hark ye, miss! pray has your mistress also hired your tongue? Madam, 'tis fine, indeed, to permit your domestics thus to address your guests.

LEONORA. 'Tis my misfortune, signora, that my want of spirits prevents me from enjoying the pleasure of your company.

JULIA. An ugly fault that, to be dull and spiritless. Be active, sprightly, witty! Yours is not the way to attach your husband to you.

LEONORA. I know but one way, Countess. Let yours ever be the sympathetic medium.

JULIA (pretending not to mind her). How you dress, madam! For shame! Pay more attention to your personal appearance! Have recourse to art where nature has been unkind. Put a little paint on those cheeks, which look so pale with spleen. Poor creature! Your puny face will never find a bidder.

LEONORA (in a lively manner to ARABELLA). Congratulate me, girl. It is impossible I can have lost my Fiesco; or, if I have, the loss must be but trifling. (The chocolate is brought, ARABELLA pours it out.)

JULIA. Do you talk of losing Fiesco? Good God! How could you ever conceive the ambitious idea of possessing him? Why, my child, aspire to such a height? A height where you cannot but be seen, and must come into comparison with others. Indeed, my dear, he was a knave or a fool who joined you with FIESCO. (Taking her hand with a look of compassion.) Poor soul! The man who is received in the assemblies of fashionable life could never be a suitable match for you. (She takes a dish of chocolate.)

LEONORA (smiling at ARABELLA). If he were, he would not wish to mix with such assemblies.

JULIA. The Count is handsome, fashionable, elegant. He is so fortunate as to have formed connections with people of rank. He is lively and high-spirited. Now, when he severs himself from these circles of elegance and refinement, and returns home warm with their impressions, what does he meet? His wife receives him with a commonplace tenderness; damps his fire with an insipid, chilling kiss, and measures out her attentions to him with a niggardly economy. Poor husband! Here, a blooming beauty smiles upon him—there he is nauseated by a peevish sensibility. Signora, signora, for God's sake consider, if he have not lost his understanding, which will he choose?

LEONORA (offering her a cup of chocolate). You, madam—if he have lost it.

JULIA. Good! This sting shall return into your own bosom. Tremble for your mockery! But before you tremble—blush!

LEONORA. Do you then know what it is to blush, signora? But why not? 'Tis a toilet trick.

JULIA. Oh, see! This poor creature must be provoked if one would draw from her a spark of wit. Well—let it pass this time. Madam, you were bitter. Give me your hand in token of reconciliation.

LEONORA (offering her hand with a significant look). Countess, my anger ne'er shall trouble you.

JULIA (offering her hand). Generous, indeed! Yet may I not be so, too? (Maliciously.) Countess, do you not think I must love that person whose image I bear constantly about me?

LEONORA (blushing and confused). What do you say? Let me hope the conclusion is too hasty.

JULIA. I think so, too. The heart waits not the guidance of the senses —real sentiment needs no breastwork of outward ornament.

LEONORA. Heavens! Where did you learn such a truth?

JULIA. 'Twas in mere compassion that I spoke it; for observe, madam, the reverse is no less certain. Such is Fiesco's love for you. (Gives her the picture, laughing maliciously.)

LEONORA (with extreme indignation). My picture! Given to you! (Throws herself into a chair, much affected.) Cruel, Fiesco!

JULIA. Have I retaliated? Have I? Now, madam, have you any other sting to wound me with? (Goes to side scene.) My carriage! My object is gained. (To LEONORA, patting her cheek.) Be comforted, my dear; he gave me the picture in a fit of madness.

[Exeunt JULIA and ARABELLA.

SCENE III.

LEONORA, CALCAGNO entering.

CALCAGNO. Did not the Countess Imperiali depart in anger? You, too, so excited, madam?

LEONORA (violently agitated.) No! This is unheard-of cruelty.

CALCAGNO. Heaven and earth! Do I behold you in tears?

LEONORA. Thou art a friend of my inhuman—Away, leave my sight!

CALCAGNO. Whom do you call inhuman? You affright me——

LEONORA. My husband. Is he not so?

CALCAGNO. What do I hear!

LEONORA. 'Tis but a piece of villany common enough among your sex!

CALCAGNO (grasping her hand with vehemence). Lady, I have a heart for weeping virtue.

LEONORA. You are a man—your heart is not for me.

CALCAGNO. For you alone—yours only. Would that you knew how much, how truly yours——

LEONORA. Man, thou art untrue. Thy words would be refuted by thy actions——

CALCAGNO. I swear to you——

LEONORA. A false oath. Cease! The perjuries of men are so innumerable 'twould tire the pen of the recording angel to write them down. If their violated oaths were turned into as many devils they might storm heaven itself, and lead away the angels of light as captives.

CALCAGNO. Nay, madam, your anger makes you unjust. Is the whole sex to answer for the crime of one?

LEONORA. I tell thee in that one was centred all my affection for the sex. In him I will detest them all.

CALCAGNO. Countess,—you once bestowed your hand amiss. Would you again make trial, I know one who would deserve it better.

LEONORA. The limits of creation cannot bound your falsehoods. I'll hear no more.

CALCAGNO. Oh, that you would retract this cruel sentence in my arms!

LEONORA (with astonishment). Speak out. In thy arms!

CALCAGNO. In my arms, which open themselves to receive a forsaken woman, and to console her for the love she has lost.

LEONORA (fixing her eyes on him). Love?

CALCAGNO (kneeling before her with ardor). Yes, I have said it. Love, madam! Life and death hang on your tongue. If my passion be criminal then let the extremes of virtue and vice unite, and heaven and hell be joined together in one perdition.

LEONORA (steps back indignantly, with a look of noble disdain). Ha! Hypocrite! Was that the object of thy false compassion? This attitude at once proclaims thee a traitor to friendship and to love. Begone forever from my eyes! Detested sex! Till now I thought the only victim of your snares was woman; nor ever suspected that to each other you were so false and faithless.

CALCAGNO (rising, confounded). Countess!

LEONORA. Was it not enough to break the sacred seal of confidence? but even on the unsullied mirror of virtue does this hypocrite breathe pestilence, and would seduce my innocence to perjury.

CALCAGNO (hastily). Perjury, madam, you cannot be guilty of.

LEONORA. I understand thee—thou thoughtest my wounded pride would plead in thy behalf. (With dignity). Thou didst not know that she who loves Fiesco feels even the pang that rends her heart ennobling. Begone! Fiesco's perfidy will not make Calcagno rise in my esteem—but—will lower humanity. [Exit hastily.

CALCAGNO (stands as if thunderstruck, looks after her, then striking his forehead). Fool that I am. [Exit.

SCENE IV.

The MOOR and FIESCO.

FIESCO. Who was it that just now departed?

MOOR. The Marquis Calcagno.

FIESCO. This handkerchief was left upon the sofa. My wife has been here.

MOOR. I met her this moment in great agitation.

FIESCO. This handkerchief is moist (puts it in his pocket). Calcagno here? And Leonora agitated? This evening thou must learn what has happened.

MOOR. Miss Bella likes to hear that she is fair. She will inform me.

FIESCO. Well—thirty hours are past. Hast thou executed my commission?

MOOR. To the letter, my lord.

FIESCO (seating himself). Then tell me how they talk of Doria, and of the government.

MOOR. Oh, most vilely. The very name of Doria shakes them like an ague-fit. Gianettino is as hateful to them as death itself—there's naught but murmuring. They say the French have been the rats of Genoa, the cat Doria has devoured them, and now is going to feast upon the mice.

FIESCO. That may perhaps be true. But do they not know of any dog against that cat?

MOOR (with an affected carelessness). The town was murmuring much of a certain—poh—why, I have actually forgotten the name.

FIESCO (rising). Blockhead! That name is as easy to be remembered as 'twas difficult to achieve. Has Genoa more such names than one?

MOOR. No—it cannot have two Counts of Lavagna.

FIESCO (seating himself). That is something. And what do they whisper about my gayeties?

MOOR (fixing his eyes upon him). Hear me, Count of Lavagna! Genoa must think highly of you. They can not imagine why a descendant of the first family—with such talents and genius—full of spirit and popularity— master of four millions—his veins enriched with princely blood—a nobleman like Fiesco, whom, at the first call, all hearts would fly to meet——

FIESCO (turns away contemptuously). To hear such things from such a scoundrel!

MOOR. Many lamented that the chief of Genoa should slumber over the ruin of his country. And many sneered. Most men condemned you. All bewailed the state which thus had lost you. A Jesuit pretended to have smelt out the fox that lay disguised in sheep's clothing.

FIESCO. One fox smells out another. What say they to my passion for the Countess Imperiali?

MOOR. What I would rather be excused from repeating.

FIESCO. Out with it—the bolder the more welcome. What are their murmurings?

MOOR. 'Tis not a murmur. At all the coffee-houses, billiard-tables, hotels, and public walks—in the market-place, at the Exchange, they proclaim aloud——

FIESCO. What? I command thee!

MOOR (retreating). That you are a fool!

FIESCO. Well, take this sequin for these tidings. Now have I put on a fool's cap that these Genoese may have wherewith to rack their wits. Next I will shave my head, that they may play Merry Andrew to my Clown. How did the manufacturers receive my presents?

MOOR (humorously). Why, Mr. Fool, they looked like poor knaves——

FIESCO. Fool? Fellow, art thou mad?

MOOR. Pardon! I had a mind for a few more sequins.

FIESCO (laughing, gives him another sequin). Well. "Like poor knaves."

MOOR. Who receive pardon at the very block. They are yours both soul and body.

FIESCO. I'm glad of it. They turn the scale among the populace of Genoa.

MOOR. What a scene it was! Zounds! I almost acquired a relish for benevolence. They caught me round the neck like madmen. The very girls seemed in love with my black visage, that's as ill-omened as the moon in an eclipse. Gold, thought I, is omnipotent: it makes even a Moor look fair.

FIESCO. That thought was better than the soil which gave it birth. These words are favorable; but do they bespeak actions of equal import?

MOOR. Yes—as the murmuring of the distant thunder foretells the approaching storm. The people lay their heads together—they collect in parties—break off their talk whenever a stranger passes by. Throughout Genoa reigns a gloomy silence. This discontent hangs like a threatening tempest over the republic. Come, wind, then hail and lightning will burst forth.

FIESCO. Hush!—hark! What is that confused noise?

MOOR (going to the window). It is the tumult of the crowd returning from the senate-house.

FIESCO. To-day is the election of a procurator. Order my carriage! It is impossible that the sitting should be over. I'll go thither. It is impossible it should be over if things went right. Bring me my sword and cloak—where is my golden chain?

MOOR. Sir, I have stolen and pawned it.

FIESCO. That I am glad to hear.

MOOR. But, how! Are there no more sequins for me?

FIESCO. No. You forgot the cloak.

MOOR. Ah! I was wrong in pointing out the thief.

FIESCO. The tumult comes nearer. Hark! 'Tis not the sound of approbation. Quick! Unlock the gates; I guess the matter. Doria has been rash. The state balances upon a needle's point. There has assuredly been some disturbance at the senate-house.

MOOR (at the window). What's here! They're coming down the street of Balbi—a crowd of many thousands—the halberds glitter—ah, swords too! Halloo! Senators! They come this way.

FIESCO. Sedition is on foot. Hasten amongst them; mention my name; persuade them to come hither. (Exit Moon hastily.) What reason, laboring like a careful ant, with difficulty scrapes together, the wind of accident collects in one short moment.

SCENE V.

FIESCO, ZENTURIONE, ZIBO, and ASSERATO, rushing in.

ZIBO. Count, impute it to our anger that we enter thus unannounced.

ZENTURIONE. I have been mortally affronted by the duke's nephew in the face of the whole senate.

ASSERATO. Doria has trampled on the golden book of which each noble Genoese is a leaf.

ZENTURIONE. Therefore come we hither. The whole nobility are insulted in me; the whole nobility must share my vengeance. To avenge my own honor I should not need assistance.

ZIBO. The whole nobility are outraged in his person; the whole nobility must rise and vent their rage in fire and flames.

ASSERATO. The rights of the nation are trodden under foot; the liberty of the republic has received a deadly blow.

FIESCO. You raise my expectation to the utmost.

ZIBO. He was the twenty-ninth among the electing senators, and had drawn forth a golden ball to vote for the procurator. Of the eight-and-twenty votes collected, fourteen were for me, and as many for Lomellino. His and Doria's were still wanting——

ZENTURIONE. Wanting! I gave my vote for Zibo. Doria—think of the wound inflicted on my honor—Doria——

ASSERATO (interrupting him). Such a thing was never heard of since the sea washed the walls of Genoa.

ZENTURIONE (continues, with great heat). Doria drew a sword, which he had concealed under a scarlet cloak—stuck it through my vote—called to the assembly——

ZIBO. "Senators, 'tis good-for-nothing—'tis pierced through. Lomellino is procurator."

ZENTURIONE. "Lomellino is procurator." And threw his sword upon the table.

ASSERATO. And called out, "'Tis good-for-nothing!" and threw his sword upon the table.

FIESCO (after a pause). On what are you resolved?

ZENTURIONE. The republic is wounded to its very heart. On what are we resolved?

FIESCO. Zenturione, rushes may yield to a breath, but the oak requires a storm. I ask, on what are you resolved?

ZIBO. Methinks the question shall be, on what does Genoa resolve?

FIESCO. Genoa! Genoa! name it not. 'Tis rotten, and crumbles wherever you touch it. Do you reckon on the nobles? Perhaps because they put on grave faces, look mysterious when state affairs are mentioned—talk not of them! Their heroism is stifled among the bales of their Levantine merchandise. Their souls hover anxiously over their India fleet.

ZENTURIONE. Learn to esteem our nobles more justly. Scarcely was Doria's haughty action done when hundreds of them rushed into the street tearing their garments. The senate was dispersed——

FIESCO (sarcastically). Like frighted pigeons when the vulture darts upon the dovecot.

ZENTURIONE. No! (fiercely)—like powder-barrels when a match falls on them.

ZIBO. The people are enraged. What may we not expect from the fury of the wounded boar!

FIESCO (laughing). The blind, unwieldy monster, which at first rattles its heavy bones, threatening, with gaping jaws, to devour the high and low, the near and distant, at last stumbles at a thread—Genoese, 'tis in vain! The epoch of the masters of the sea is past—Genoa is sunk beneath the splendor of its name. Its state is such as once was Rome's, when, like a tennis-ball, she leaped into the racket of young Octavius. Genoa can be free no longer; Genoa must be fostered by a monarch; therefore do homage to the mad-brained Gianettino.

ZENTURIONE (vehemently). Yes, when the contending elements are reconciled, and when the north pole meets the south. Come, friends.

FIESCO. Stay! stay! Upon what project are you brooding, Zibo?

ZIBO. On nothing.

FIESCO (leading them to a statue). Look at this figure.

ZENTURIONE. It is the Florentine Venus. Why point to her?

FIESCO. At least she pleases you.

ZIBO. Undoubtedly, or we should be but poor Italians. But why this question now?

FIESCO. Travel through all the countries of the globe, and among the most beautiful of living female models, seek one which shall unite all the charms of this ideal Venus.

ZIBO. And then take for our reward?

FIESCO. Then your search will have convicted fancy of deceit——

ZENTURIONE (impatiently). And what shall we have gained?

FIESCO. Gained? The decision of the long-protracted contest between art and nature.

ZENTURIONE (eagerly). And what then?

FIESCO. Then, then? (Laughing.) Then your attention will have been diverted from observing the fall of Genoa's liberty.

[Exeunt all but FIESCO.

SCENE VI.

FIESCO alone. (The noise without increases.)

FIESCO. 'Tis well! 'tis well. The straw of the republic has caught fire—the flames have seized already on palaces and towers. Let it go on! May the blaze be general! Let the tempestuous wind spread wide the conflagration!

SCENE VII.

FIESCO, MOOR, entering in haste.

MOOR. Crowds upon crowds!

FIESCO. Throw open wide the gates. Let all that choose enter.

MOOR. Republicans! Republicans, indeed! They drag their liberty along, panting, like beasts of burden, beneath the yoke of their magnificent nobility.

FIESCO. Fools! who believe that Fiesco of Lavagna will carry on what Fiesco of Lavagna did not begin. The tumult comes opportunely; but the conspiracy must be my own. They are rushing hither——

MOOR (going out). Halloo! halloo! You are very obligingly battering the house down. (The people rush in; the doors broken down.)

SCENE VIII.

FIESCO, twelve ARTISANS.

ALL ARTISANS. Vengeance on Doria! Vengeance on Gianettino!

FIESCO. Gently! gently! my countrymen! Your waiting thus upon me bespeaks the warmth of your affection; but I pray you have mercy on my ears!

ALL (with impetuosity). Down with the Dorias! Down with them, uncle and nephew!

FIESCO (counting them with a smile). Twelve is a mighty force!

SOME OF THEM. These Dorias must away! the state must be reformed!

1ST ARTISAN. To throw our magistrates down stairs! The magistrates!

2D ARTISAN. Think, Count Lavagna—down stairs! because they opposed them in the election——

ALL. It must not be endured! it shall not be endured!

3D ARTISAN. To take a sword into the senate!

1ST ARTISAN. A sword?—the sign of war—into the chamber of peace!

2D ARTISAN. To come into the senate dressed in scarlet! Not like the other senators, in black.

1ST ARTISAN. To drive through our capital with eight horses!

ALL. A tyrant! A traitor to the country and the government!

2D ARTISAN. To hire two hundred Germans from the Emperor for his body-guard.

1ST ARTISAN. To bring foreigners in arms against the natives—Germans against Italians—soldiers against laws!

ALL. 'Tis treason!—'tis a plot against the liberty of Genoa!

1ST ARTISAN. To have the arms of the republic painted on his coach!

2D ARTISAN. The statue of Andreas placed in the centre of the senate-house!

ALL. Dash them to pieces—both the statue and the man——

FIESCO. Citizens of Genoa, why this to me?

1ST ARTISAN. You should not suffer it. You should keep him down.

2D ARTISAN. You are a wise man, and should not suffer it. You should direct us by your counsel.

1ST ARTISAN. You are a better nobleman. You should chastise them and curb their insolence.

FIESCO. Your confidence is flattering. Can I merit it by deeds?

ALL (clamorously). Strike! Down with the tyrant! Make us free!

FIESCO. But—will you hear me?

SOME. Speak, Count!

FIESCO (seating himself). Genoese,—the empire of the animals was once thrown into confusion; parties struggled with parties, till at last a bull-dog seized the throne. He, accustomed to drive the cattle to the knife of the butcher, prowled in savage manner through the state. He barked, he bit, and gnawed his subjects' bones. The nation murmured; the boldest joined together, and killed the princely monster. Now a general assembly was held to decide upon the important question, which form of government was best. There were three different opinions. Genoese, what would be your decision?

1ST ARTISAN. For the people—everything in common——

FIESCO. The people gained it. The government was democratical; each citizen had a vote, and everything was submitted to a majority. But a few weeks passed ere man declared war against the new republic. The state assembled. Horse, lion, tiger, bear, elephant, and rhinoceros, stepped forth, and roared aloud, "To arms!" The rest were called upon to vote. The lamb, the hare, the stag, the ass, the tribe of insects, with the birds and timid fishes, cried for peace. See, Genoese! The cowards were more numerous than the brave; the foolish than the wise. Numbers prevailed—the beasts laid down their arms, and man exacted contributions from them. The democratic system was abandoned. Genoese, what would you next have chosen?

1ST AND 2D ARTISANS. A select government!

FIESCO. That was adopted. The business of the state was all arranged in separate departments. Wolves were the financiers, foxes their secretaries, doves presided in the criminal courts, and tigers in the courts of equity. The laws of chastity were regulated by goats; hares were the soldiers; lions and elephants had charge of the baggage. The ass was the ambassador of the empire, and the mole appointed inspector-general of the whole administration. Genoese, what think you of this wise distribution? Those whom the wolf did not devour the fox pillaged; whoever escaped from him was knocked down by the ass. The tiger murdered innocents, whilst robbers and assassins were pardoned by the doves. And at the last, when each had laid down his office, the mole declared that all were well discharged. The animals rebelled. "Let us," they cried unanimously, "choose a monarch endowed with strength and skill, and who has only one stomach to appease." And to one chief they all did homage. Genoese—to one—-but (rising and advancing majestically)—that one was—the lion!

ALL (shouting, and throwing up their hats). Bravo! Bravo! Well managed, Count Lavagna!

1ST ARTISAN. And Genoa shall follow that example. Genoa, also, has its lion!

FIESCO. Tell me not of that lion; but go home and think upon him. (The ARTISANS depart tumultuously.) It is as I would have it. The people and the senate are alike enraged against Doria; the people and the senate alike approve FIESCO. Hassan! Hassan! I must take advantage of this favorable gale. Hoa! Hassan! Hassan! I must augment their hatred— improve my influence. Hassan! Come hither! Whoreson of hell, come hither!

SCENE IX.

FIESCO, MOOR entering hastily.

MOOR. My feet are quite on fire with running. What is the matter now?

FIESCO. Hear my commands!

MOOR (submissively). Whither shall I run first?

FIESCO. I will excuse thy running this time. Thou shalt be dragged. Prepare thyself. I intend to publish thy attempted assassination, and deliver thee up in chains to the criminal tribunal.

MOOR (taking several steps backward). Sir!—that's contrary to agreement.

FIESCO. Be not alarmed. 'Tis but a farce. At this moment 'tis of the utmost consequence that Gianettino's attempt against my life should be made public. Thou shalt be tried before the criminal tribunal.

MOOR. Must I confess it, or deny?

FIESCO. Deny. They will put thee to the torture. Thou must hold out against the first degree. This, by the by, will serve to expiate thy real crime. At the second thou mayest confess.

MOOR (shaking his head with a look of apprehension). The devil is a sly rogue. Their worships might perhaps desire my company a little longer than I should wish; and, for sheer farce sake, I may be broken on the wheel.

FIESCO. Thou shalt escape unhurt, I give thee my honor as a nobleman. I shall request, as satisfaction, to have thy punishment left to me, and then pardon thee before the whole republic.

MOOR. Well—I agree to it. They will draw out my joints a little; but that will only make them the more flexible.

FIESCO. Then scratch this arm with thy dagger, till the blood flows. I will pretend that I have just now seized thee in fact. 'Tis well. (Hallooing violently). Murder! Murder! Guard the passages! Make fast the gates! (He drags the MOOR out by the throat; servants run across the stage hastily.)

SCENE X.

LEONORA and ROSA enter hastily, alarmed.

LEONORA. Murder! they cried—murder!—The noise came this way.

ROSA. Surely 'twas but a common tumult, such as happens every day in Genoa.

LEONORA. They cried murder! and I distinctly heard Fiesco's name. In vain you would deceive me. My heart discovers what is concealed from my eyes. Quick! Hasten after them. See! Tell me whither they carry him.

ROSA. Collect your spirits, madam. Arabella is gone.

LEONORA. Arabella will catch his dying look. The happy Arabella! Wretch that I am? 'twas I that murdered him. If I could have engaged his heart he would not have plunged into the world, nor rushed upon the daggers of assassins. Ah! she comes. Away! Oh, Arabella, speak not to me!

SCENE XI.

The former, ARABELLA.

ARABELLA. The Count is living and unhurt. I saw him gallop through the city. Never did he appear more handsome. The steed that bore him pranced haughtily along, and with its proud hoof kept the thronging multitude at a distance from its princely rider. He saw me as I passed, and with a gracious smile, pointing thither, thrice kissed his hand to me. (Archly.) What can I do with those kisses, madam?

LEONORA (highly pleased). Idle prattler! Restore them to him.

ROSA. See now, how soon your color has returned!

LEONORA. His heart he is ready to fling at every wench, whilst I sigh in vain for a look! Oh woman! woman!

[Exeunt.

SCENE XII.—The Palace of ANDREAS.

GIANETTINO and LOMELLINO enter hastily.

GIANETTINO. Let them roar for their liberty as a lioness for her young. I am resolved.

LOMELLINO. But—most gracious prince!

GIANETTINO. Away to hell with thy buts, thou three-hours procurator! I will not yield a hair's breadth? Let Genoa's towers shake their heads, and the hoarse sea bellow No to it. I value not the rebellious multitude!

LOMELLINO. The people are indeed the fuel; but the nobility fan the flame. The whole republic is in a ferment, people and patricians.

GIANETTINO. Then will I stand upon the mount like Nero, and regale myself with looking upon the paltry flames.

LOMELLINO. Till the whole mass of sedition falls into the hands of some enterprising leader, who will take advantage of the general devastation.

GIANETTINO. Poh! Poh! I know but one who might be dangerous, and he is taken care of.

LOMELLINO. His highness comes.

Enter ANDREAS—(both bow respectfully).

ANDREAS. Signor Lomellino, my niece wishes to take the air.

LOMELLINO. I shall have the honor of attending her.

[Exit LOMELLINO.

SCENE XIII.

ANDREAS and GIANETTINO.

ANDREAS. Nephew, I am much displeased with you.

GIANETTINO. Grant me a hearing, most gracious uncle!

ANDREAS. That would I grant to the meanest beggar in Genoa if he were worthy of it. Never to a villain, though he were my nephew. It is sufficient favor that I address thee as an uncle, not as a sovereign!

GIANETTINO. One word only, gracious sir!