Project Gutenberg's Villa Rubein and Other Stories, by John Galsworthy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Villa Rubein and Other Stories Author: John Galsworthy Release Date: June 14, 2006 [EBook #2639] Last Updated: August 5, 2016 Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK VILLA RUBEIN AND OTHER STORIES *** Produced by David Widger

CONTENTS

VILLA RUBEIN

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

XIII

XIV

XV

XVI

XVII

XVIII

XIX

XX

XXI

XXII

XXIII

XXIV

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

XXVIII

XXIX

A MAN OF DEVON

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

A KNIGHT

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

SALVATION OF A FORSYTE

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

VII

VIII

IX

X

XI

XII

THE SILENCE

I

II

III

IV

V

VI

Writing not long ago to my oldest literary friend, I expressed in a moment of heedless sentiment the wish that we might have again one of our talks of long-past days, over the purposes and methods of our art. And my friend, wiser than I, as he has always been, replied with this doubting phrase “Could we recapture the zest of that old time?”

I would not like to believe that our faith in the value of imaginative art has diminished, that we think it less worth while to struggle for glimpses of truth and for the words which may pass them on to other eyes; or that we can no longer discern the star we tried to follow; but I do fear, with him, that half a lifetime of endeavour has dulled the exuberance which kept one up till morning discussing the ways and means of aesthetic achievement. We have discovered, perhaps with a certain finality, that by no talk can a writer add a cubit to his stature, or change the temperament which moulds and colours the vision of life he sets before the few who will pause to look at it. And so—the rest is silence, and what of work we may still do will be done in that dogged muteness which is the lot of advancing years.

Other times, other men and modes, but not other truth. Truth, though essentially relative, like Einstein’s theory, will never lose its ever-new and unique quality-perfect proportion; for Truth, to the human consciousness at least, is but that vitally just relation of part to whole which is the very condition of life itself. And the task before the imaginative writer, whether at the end of the last century or all these aeons later, is the presentation of a vision which to eye and ear and mind has the implicit proportions of Truth.

I confess to have always looked for a certain flavour in the writings of others, and craved it for my own, believing that all true vision is so coloured by the temperament of the seer, as to have not only the just proportions but the essential novelty of a living thing for, after all, no two living things are alike. A work of fiction should carry the hall mark of its author as surely as a Goya, a Daumier, a Velasquez, and a Mathew Maris, should be the unmistakable creations of those masters. This is not to speak of tricks and manners which lend themselves to that facile elf, the caricaturist, but of a certain individual way of seeing and feeling. A young poet once said of another and more popular poet: “Oh! yes, but be cuts no ice.” And, when one came to think of it, he did not; a certain flabbiness of spirit, a lack of temperament, an absence, perhaps, of the ironic, or passionate, view, insubstantiated his work; it had no edge—just a felicity which passed for distinction with the crowd.

Let me not be understood to imply that a novel should be a sort of sandwich, in which the author’s mood or philosophy is the slice of ham. One’s demand is for a far more subtle impregnation of flavour; just that, for instance, which makes De Maupassant a more poignant and fascinating writer than his master Flaubert, Dickens and Thackeray more living and permanent than George Eliot or Trollope. It once fell to my lot to be the preliminary critic of a book on painting, designed to prove that the artist’s sole function was the impersonal elucidation of the truths of nature. I was regretfully compelled to observe that there were no such things as the truths of Nature, for the purposes of art, apart from the individual vision of the artist. Seer and thing seen, inextricably involved one with the other, form the texture of any masterpiece; and I, at least, demand therefrom a distinct impression of temperament. I never saw, in the flesh, either De Maupassant or Tchekov—those masters of such different methods entirely devoid of didacticism—but their work leaves on me a strangely potent sense of personality. Such subtle intermingling of seer with thing seen is the outcome only of long and intricate brooding, a process not too favoured by modern life, yet without which we achieve little but a fluent chaos of clever insignificant impressions, a kind of glorified journalism, holding much the same relation to the deeply-impregnated work of Turgenev, Hardy, and Conrad, as a film bears to a play.

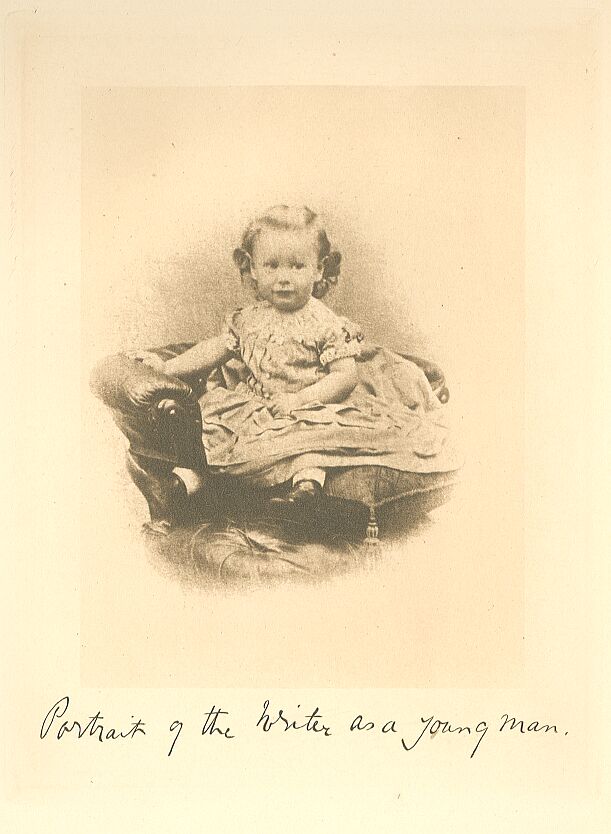

Speaking for myself, with the immodesty required of one who hazards an introduction to his own work, I was writing fiction for five years before I could master even its primary technique, much less achieve that union of seer with thing seen, which perhaps begins to show itself a little in this volume—binding up the scanty harvests of 1899, 1900, and 1901—especially in the tales: “A Knight,” and “Salvation of a Forsyte.” Men, women, trees, and works of fiction—very tiny are the seeds from which they spring. I used really to see the “Knight”—in 1896, was it?—sitting in the “Place” in front of the Casino at Monte Carlo; and because his dried-up elegance, his burnt straw hat, quiet courtesy of attitude, and big dog, used to fascinate and intrigue me, I began to imagine his life so as to answer my own questions and to satisfy, I suppose, the mood I was in. I never spoke to him, I never saw him again. His real story, no doubt, was as different from that which I wove around his figure as night from day.

As for Swithin, wild horses will not drag from me confession of where and when I first saw the prototype which became enlarged to his bulky stature. I owe Swithin much, for he first released the satirist in me, and is, moreover, the only one of my characters whom I killed before I gave him life, for it is in “The Man of Property” that Swithin Forsyte more memorably lives.

Ranging beyond this volume, I cannot recollect writing the first words of “The Island Pharisees”—but it would be about August, 1901. Like all the stories in “Villa Rubein,” and, indeed, most of my tales, the book originated in the curiosity, philosophic reflections, and unphilosophic emotions roused in me by some single figure in real life. In this case it was Ferrand, whose real name, of course, was not Ferrand, and who died in some “sacred institution” many years ago of a consumption brought on by the conditions of his wandering life. If not “a beloved,” he was a true vagabond, and I first met him in the Champs Elysees, just as in “The Pigeon” he describes his meeting with Wellwyn. Though drawn very much from life, he did not in the end turn out very like the Ferrand of real life—the figures of fiction soon diverge from their prototypes.

The first draft of “The Island Pharisees” was buried in a drawer; when retrieved the other day, after nineteen years, it disclosed a picaresque string of anecdotes told by Ferrand in the first person. These two-thirds of a book were laid to rest by Edward Garnett’s dictum that its author was not sufficiently within Ferrand’s skin; and, struggling heavily with laziness and pride, he started afresh in the skin of Shelton. Three times be wrote that novel, and then it was long in finding the eye of Sydney Pawling, who accepted it for Heinemann’s in 1904. That was a period of ferment and transition with me, a kind of long awakening to the home truths of social existence and national character. The liquor bubbled too furiously for clear bottling. And the book, after all, became but an introduction to all those following novels which depict—somewhat satirically—the various sections of English “Society” with a more or less capital “S.”

Looking back on the long-stretched-out body of one’s work, it is interesting to mark the endless duel fought within a man between the emotional and critical sides of his nature, first one, then the other, getting the upper hand, and too seldom fusing till the result has the mellowness of full achievement. One can even tell the nature of one’s readers, by their preference for the work which reveals more of this side than of that. My early work was certainly more emotional than critical. But from 1901 came nine years when the critical was, in the main, holding sway. From 1910 to 1918 the emotional again struggled for the upper hand; and from that time on there seems to have been something of a “dead beat.” So the conflict goes, by what mysterious tides promoted, I know not.

An author must ever wish to discover a hapless member of the Public who, never yet having read a word of his writing, would submit to the ordeal of reading him right through from beginning to end. Probably the effect could only be judged through an autopsy, but in the remote case of survival, it would interest one so profoundly to see the differences, if any, produced in that reader’s character or outlook over life. This, however, is a consummation which will remain devoutly to be wished, for there is a limit to human complaisance. One will never know the exact measure of one’s infecting power; or whether, indeed, one is not just a long soporific.

A writer they say, should not favouritize among his creations; but then a writer should not do so many things that he does. This writer, certainly, confesses to having favourites, and of his novels so far be likes best: The Forsyte Series; “The Country House”; “Fraternity”; “The Dark Flower”; and “Five Tales”; believing these to be the works which most fully achieve fusion of seer with thing seen, most subtly disclose the individuality of their author, and best reveal such of truth as has been vouchsafed to him. JOHN GALSWORTHY.

Walking along the river wall at Botzen, Edmund Dawney said to Alois Harz: “Would you care to know the family at that pink house, Villa Rubein?”

Harz answered with a smile:

“Perhaps.”

“Come with me then this afternoon.”

They had stopped before an old house with a blind, deserted look, that stood by itself on the wall; Harz pushed the door open.

“Come in, you don’t want breakfast yet. I’m going to paint the river to-day.”

He ran up the bare broad stairs, and Dawney followed leisurely, his thumbs hooked in the armholes of his waistcoat, and his head thrown back.

In the attic which filled the whole top story, Harz had pulled a canvas to the window. He was a young man of middle height, square shouldered, active, with an angular face, high cheek-bones, and a strong, sharp chin. His eyes were piercing and steel-blue, his eyebrows very flexible, nose long and thin with a high bridge; and his dark, unparted hair fitted him like a cap. His clothes looked as if he never gave them a second thought.

This room, which served for studio, bedroom, and sitting-room, was bare and dusty. Below the window the river in spring flood rushed down the valley, a stream, of molten bronze. Harz dodged before the canvas like a fencer finding his distance; Dawney took his seat on a packingcase.

“The snows have gone with a rush this year,” he drawled. “The Talfer comes down brown, the Eisack comes down blue; they flow into the Etsch and make it green; a parable of the Spring for you, my painter.”

Harz mixed his colours.

“I’ve no time for parables,” he said, “no time for anything. If I could be guaranteed to live to ninety-nine, like Titian—he had a chance. Look at that poor fellow who was killed the other day! All that struggle, and then—just at the turn!”

He spoke English with a foreign accent; his voice was rather harsh, but his smile very kindly.

Dawney lit a cigarette.

“You painters,” he said, “are better off than most of us. You can strike out your own line. Now if I choose to treat a case out of the ordinary way and the patient dies, I’m ruined.”

“My dear Doctor—if I don’t paint what the public likes, I starve; all the same I’m going to paint in my own way; in the end I shall come out on top.”

“It pays to work in the groove, my friend, until you’ve made your name; after that—do what you like, they’ll lick your boots all the same.”

“Ah, you don’t love your work.”

Dawney answered slowly: “Never so happy as when my hands are full. But I want to make money, to get known, to have a good time, good cigars, good wine. I hate discomfort. No, my boy, I must work it on the usual lines; I don’t like it, but I must lump it. One starts in life with some notion of the ideal—it’s gone by the board with me. I’ve got to shove along until I’ve made my name, and then, my little man—then—”

“Then you’ll be soft!”

“You pay dearly for that first period!”

“Take my chance of that; there’s no other way.”

“Make one!”

“Humph!”

Harz poised his brush, as though it were a spear:

“A man must do the best in him. If he has to suffer—let him!”

Dawney stretched his large soft body; a calculating look had come into his eyes.

“You’re a tough little man!” he said.

“I’ve had to be tough.”

Dawney rose; tobacco smoke was wreathed round his unruffled hair.

“Touching Villa Rubein,” he said, “shall I call for you? It’s a mixed household, English mostly—very decent people.”

“No, thank you. I shall be painting all day. Haven’t time to know the sort of people who expect one to change one’s clothes.”

“As you like; ta-to!” And, puffing out his chest, Dawney vanished through a blanket looped across the doorway.

Harz set a pot of coffee on a spirit-lamp, and cut himself some bread. Through the window the freshness of the morning came; the scent of sap and blossom and young leaves; the scent of earth, and the mountains freed from winter; the new flights and songs of birds; all the odorous, enchanted, restless Spring.

There suddenly appeared through the doorway a white rough-haired terrier dog, black-marked about the face, with shaggy tan eyebrows. He sniffed at Harz, showed the whites round his eyes, and uttered a sharp bark. A young voice called:

“Scruff! Thou naughty dog!” Light footsteps were heard on the stairs; from the distance a thin, high voice called:

“Greta! You mustn’t go up there!”

A little girl of twelve, with long fair hair under a wide-brimmed hat, slipped in.

Her blue eyes opened wide, her face flushed up. That face was not regular; its cheek-bones were rather prominent, the nose was flattish; there was about it an air, innocent, reflecting, quizzical, shy.

“Oh!” she said.

Harz smiled: “Good-morning! This your dog?”

She did not answer, but looked at him with soft bewilderment; then running to the dog seized him by the collar.

“Scr-ruff! Thou naughty dog—the baddest dog!” The ends of her hair fell about him; she looked up at Harz, who said:

“Not at all! Let me give him some bread.”

“Oh no! You must not—I will beat him—and tell him he is bad; then he shall not do such things again. Now he is sulky; he looks so always when he is sulky. Is this your home?”

“For the present; I am a visitor.”

“But I think you are of this country, because you speak like it.”

“Certainly, I am a Tyroler.”

“I have to talk English this morning, but I do not like it very much—because, also I am half Austrian, and I like it best; but my sister, Christian, is all English. Here is Miss Naylor; she shall be very angry with me.”

And pointing to the entrance with a rosy-tipped forefinger, she again looked ruefully at Harz.

There came into the room with a walk like the hopping of a bird an elderly, small lady, in a grey serge dress, with narrow bands of claret-coloured velveteen; a large gold cross dangled from a steel chain on her chest; she nervously twisted her hands, clad in black kid gloves, rather white about the seams.

Her hair was prematurely grey; her quick eyes brown; her mouth twisted at one corner; she held her face, kind-looking, but long and narrow, rather to one side, and wore on it a look of apology. Her quick sentences sounded as if she kept them on strings, and wanted to draw them back as soon as she had let them forth.

“Greta, how can, you do such things? I don’t know what your father would say! I am sure I don’t know how to—so extraordinary—”

“Please!” said Harz.

“You must come at once—so very sorry—so awkward!” They were standing in a ring: Harz with his eyebrows working up and down; the little lady fidgeting her parasol; Greta, flushed and pouting, her eyes all dewy, twisting an end of fair hair round her finger.

“Oh, look!” The coffee had boiled over. Little brown streams trickled spluttering from the pan; the dog, with ears laid back and tail tucked in, went scurrying round the room. A feeling of fellowship fell on them at once.

“Along the wall is our favourite walk, and Scruff—so awkward, so unfortunate—we did not think any one lived here—the shutters are cracked, the paint is peeling off so dreadfully. Have you been long in Botzen? Two months? Fancy! You are not English? You are Tyrolese? But you speak English so well—there for seven years? Really? So fortunate!—It is Greta’s day for English.”

Miss Naylor’s eyes darted bewildered glances at the roof where the crossing of the beams made such deep shadows; at the litter of brushes, tools, knives, and colours on a table made out of packing-cases; at the big window, innocent of glass, and flush with the floor, whence dangled a bit of rusty chain—relic of the time when the place had been a store-loft; her eyes were hastily averted from an unfinished figure of the nude.

Greta, with feet crossed, sat on a coloured blanket, dabbling her finger in a little pool of coffee, and gazing up at Harz. And he thought: ‘I should like to paint her like that. “A forget-me-not.”

He took out his chalks to make a sketch of her.

“Shall you show me?” cried out Greta, scrambling to her feet.

“‘Will,’ Greta—’will’. how often must I tell you? I think we should be going—it is very late—your father—so very kind of you, but I think we should be going. Scruff!” Miss Naylor gave the floor two taps. The terrier backed into a plaster cast which came down on his tail, and sent him flying through the doorway. Greta followed swiftly, crying:

“Ach! poor Scrufee!”

Miss Naylor crossed the room; bowing, she murmured an apology, and also disappeared.

Harz was left alone, his guests were gone; the little girl with the fair hair and the eyes like forget-me-nots, the little lady with kindly gestures and bird-like walk, the terrier. He looked round him; the room seemed very empty. Gnawing his moustache, he muttered at the fallen cast.

Then taking up his brush, stood before his picture, smiling and frowning. Soon he had forgotten it all in his work.

It was early morning four days later, and Harz was loitering homewards. The shadows of the clouds passing across the vines were vanishing over the jumbled roofs and green-topped spires of the town. A strong sweet wind was blowing from the mountains, there was a stir in the branches of the trees, and flakes of the late blossom were drifting down. Amongst the soft green pods of a kind of poplar chafers buzzed, and numbers of their little brown bodies were strewn on the path.

He passed a bench where a girl sat sketching. A puff of wind whirled her drawing to the ground; Harz ran to pick it up. She took it from him with a bow; but, as he turned away, she tore the sketch across.

“Ah!” he said; “why did you do that?”

This girl, who stood with a bit of the torn sketch in either hand, was slight and straight; and her face earnest and serene. She gazed at Harz with large, clear, greenish eyes; her lips and chin were defiant, her forehead tranquil.

“I don’t like it.”

“Will you let me look at it? I am a painter.”

“It isn’t worth looking at, but—if you wish—”

He put the two halves of the sketch together.

“You see!” she said at last; “I told you.”

Harz did not answer, still looking at the sketch. The girl frowned.

Harz asked her suddenly:

“Why do you paint?”

She coloured, and said:

“Show me what is wrong.”

“I cannot show you what is wrong, there is nothing wrong—but why do you paint?”

“I don’t understand.”

Harz shrugged his shoulders.

“You’ve no business to do that,” said the girl in a hurt voice; “I want to know.”

“Your heart is not in it,” said Harz.

She looked at him, startled; her eyes had grown thoughtful.

“I suppose that is it. There are so many other things—”

“There should be nothing else,” said Harz.

She broke in: “I don’t want always to be thinking of myself. Suppose—”

“Ah! When you begin supposing!”

The girl confronted him; she had torn the sketch again.

“You mean that if it does not matter enough, one had better not do it at all. I don’t know if you are right—I think you are.”

There was the sound of a nervous cough, and Harz saw behind him his three visitors—Miss Naylor offering him her hand; Greta, flushed, with a bunch of wild flowers, staring intently in his face; and the terrier, sniffing at his trousers.

Miss Naylor broke an awkward silence.

“We wondered if you would still be here, Christian. I am sorry to interrupt you—I was not aware that you knew Mr. Herr—”

“Harz is my name—we were just talking”

“About my sketch. Oh, Greta, you do tickle! Will you come and have breakfast with us to-day, Herr Harz? It’s our turn, you know.”

Harz, glancing at his dusty clothes, excused himself.

But Greta in a pleading voice said: “Oh! do come! Scruff likes you. It is so dull when there is nobody for breakfast but ourselves.”

Miss Naylor’s mouth began to twist. Harz hurriedly broke in:

“Thank you. I will come with pleasure; you don’t mind my being dirty?”

“Oh no! we do not mind; then we shall none of us wash, and afterwards I shall show you my rabbits.”

Miss Naylor, moving from foot to foot, like a bird on its perch, exclaimed:

“I hope you won’t regret it, not a very good meal—the girls are so impulsive—such informal invitation; we shall be very glad.”

But Greta pulled softly at her sister’s sleeve, and Christian, gathering her things, led the way.

Harz followed in amazement; nothing of this kind had come into his life before. He kept shyly glancing at the girls; and, noting the speculative innocence in Greta’s eyes, he smiled. They soon came to two great poplar-trees, which stood, like sentinels, one on either side of an unweeded gravel walk leading through lilac bushes to a house painted dull pink, with green-shuttered windows, and a roof of greenish slate. Over the door in faded crimson letters were written the words, “Villa Rubein.”

“That is to the stables,” said Greta, pointing down a path, where some pigeons were sunning themselves on a wall. “Uncle Nic keeps his horses there: Countess and Cuckoo—his horses begin with C, because of Chris—they are quite beautiful. He says he could drive them to Kingdom-Come and they would not turn their hair. Bow, and say ‘Good-morning’ to our house!”

Harz bowed.

“Father said all strangers should, and I think it brings good luck.” From the doorstep she looked round at Harz, then ran into the house.

A broad, thick-set man, with stiff, brushed-up hair, a short, brown, bushy beard parted at the chin, a fresh complexion, and blue glasses across a thick nose, came out, and called in a bluff voice:

“Ha! my good dears, kiss me quick—prrt! How goes it then this morning? A good walk, hein?” The sound of many loud rapid kisses followed.

“Ha, Fraulein, good!” He became aware of Harz’s figure standing in the doorway: “Und der Herr?”

Miss Naylor hurriedly explained.

“Good! An artist! Kommen Sie herein, I am delight. You will breakfast? I too—yes, yes, my dears—I too breakfast with you this morning. I have the hunter’s appetite.”

Harz, looking at him keenly, perceived him to be of middle height and age, stout, dressed in a loose holland jacket, a very white, starched shirt, and blue silk sash; that he looked particularly clean, had an air of belonging to Society, and exhaled a really fine aroma of excellent cigars and the best hairdresser’s essences.

The room they entered was long and rather bare; there was a huge map on the wall, and below it a pair of globes on crooked supports, resembling two inflated frogs erect on their hind legs. In one corner was a cottage piano, close to a writing-table heaped with books and papers; this nook, sacred to Christian, was foreign to the rest of the room, which was arranged with supernatural neatness. A table was laid for breakfast, and the sun-warmed air came in through French windows.

The meal went merrily; Herr Paul von Morawitz was never in such spirits as at table. Words streamed from him. Conversing with Harz, he talked of Art as who should say: “One does not claim to be a connoisseur—pas si bete—still, one has a little knowledge, que diable!” He recommended him a man in the town who sold cigars that were “not so very bad.” He consumed porridge, ate an omelette; and bending across to Greta gave her a sounding kiss, muttering: “Kiss me quick!”—an expression he had picked up in a London music-hall, long ago, and considered chic. He asked his daughters’ plans, and held out porridge to the terrier, who refused it with a sniff.

“Well,” he said suddenly, looking at Miss Naylor, “here is a gentleman who has not even heard our names!”

The little lady began her introductions in a breathless voice.

“Good!” Herr Paul said, puffing out his lips: “Now we know each other!” and, brushing up the ends of his moustaches, he carried off Harz into another room, decorated with pipe-racks, prints of dancing-girls, spittoons, easy-chairs well-seasoned by cigar smoke, French novels, and newspapers.

The household at Villa Rubein was indeed of a mixed and curious nature. Cut on both floors by corridors, the Villa was divided into four divisions; each of which had its separate inhabitants, an arrangement which had come about in the following way:

When old Nicholas Treffry died, his estate, on the boundary of Cornwall, had been sold and divided up among his three surviving children—Nicholas, who was much the eldest, a partner in the well-known firm of Forsyte and Treffry, teamen, of the Strand; Constance, married to a man called Decie; and Margaret, at her father’s death engaged to the curate of the parish, John Devorell, who shortly afterwards became its rector. By his marriage with Margaret Treffry the rector had one child called Christian. Soon after this he came into some property, and died, leaving it unfettered to his widow. Three years went by, and when the child was six years old, Mrs. Devorell, still young and pretty, came to live in London with her brother Nicholas. It was there that she met Paul von Morawitz—the last of an old Czech family, who had lived for many hundred years on their estates near Budweiss. Paul had been left an orphan at the age of ten, and without a solitary ancestral acre. Instead of acres, he inherited the faith that nothing was too good for a von Morawitz. In later years his savoir faire enabled him to laugh at faith, but it stayed quietly with him all the same. The absence of acres was of no great consequence, for through his mother, the daughter of a banker in Vienna, he came into a well-nursed fortune. It befitted a von Morawitz that he should go into the Cavalry, but, unshaped for soldiering, he soon left the Service; some said he had a difference with his Colonel over the quality of food provided during some manoeuvres; others that he had retired because his chargers did not fit his legs, which were, indeed, rather round.

He had an admirable appetite for pleasure; a man-about-town’s life suited him. He went his genial, unreflecting, costly way in Vienna, Paris, London. He loved exclusively those towns, and boasted that he was as much at home in one as in another. He combined exuberant vitality with fastidiousness of palate, and devoted both to the acquisition of a special taste in women, weeds, and wines; above all he was blessed with a remarkable digestion. He was thirty when he met Mrs. Devorell; and she married him because he was so very different from anybody she had ever seen. People more dissimilar were never mated. To Paul—accustomed to stage doors—freshness, serene tranquillity, and obvious purity were the baits; he had run through more than half his fortune, too, and the fact that she had money was possibly not overlooked. Be that as it may, he was fond of her; his heart was soft, he developed a domestic side.

Greta was born to them after a year of marriage. The instinct of the “freeman” was, however, not dead in Paul; he became a gambler. He lost the remainder of his fortune without being greatly disturbed. When he began to lose his wife’s fortune too things naturally became more difficult. Not too much remained when Nicholas Treffry stepped in, and caused his sister to settle what was left on her daughters, after providing a life-interest for herself and Paul. Losing his supplies, the good man had given up his cards. But the instinct of the “freeman” was still living in his breast; he took to drink. He was never grossly drunk, and rarely very sober. His wife sorrowed over this new passion; her health, already much enfeebled, soon broke down. The doctors sent her to the Tyrol. She seemed to benefit by this, and settled down at Botzen. The following year, when Greta was just ten, she died. It was a shock to Paul. He gave up excessive drinking; became a constant smoker, and lent full rein to his natural domesticity. He was fond of both the girls, but did not at all understand them; Greta, his own daughter, was his favourite. Villa Rubein remained their home; it was cheap and roomy. Money, since Paul became housekeeper to himself, was scarce.

About this time Mrs. Decie, his wife’s sister, whose husband had died in the East, returned to England; Paul invited her to come and live with them. She had her own rooms, her own servant; the arrangement suited Paul—it was economically sound, and there was some one always there to take care of the girls. In truth he began to feel the instinct of the “freeman” rising again within him; it was pleasant to run over to Vienna now and then; to play piquet at a Club in Gries, of which he was the shining light; in a word, to go “on the tiles” a little. One could not always mourn—even if a woman were an angel; moreover, his digestion was as good as ever.

The fourth quarter of this Villa was occupied by Nicholas Treffry, whose annual sojourn out of England perpetually surprised himself. Between him and his young niece, Christian, there existed, however, a rare sympathy; one of those affections between the young and old, which, mysteriously born like everything in life, seems the only end and aim to both, till another feeling comes into the younger heart.

Since a long and dangerous illness, he had been ordered to avoid the English winter, and at the commencement of each spring he would appear at Botzen, driving his own horses by easy stages from the Italian Riviera, where he spent the coldest months. He always stayed till June before going back to his London Club, and during all that time he let no day pass without growling at foreigners, their habits, food, drink, and raiment, with a kind of big dog’s growling that did nobody any harm. The illness had broken him very much; he was seventy, but looked more. He had a servant, a Luganese, named Dominique, devoted to him. Nicholas Treffry had found him overworked in an hotel, and had engaged him with the caution: “Look—here, Dominique! I swear!” To which Dominique, dark of feature, saturnine and ironical, had only replied: “Tres biens, M’sieur!”

Harz and his host sat in leather chairs; Herr Paul’s square back was wedged into a cushion, his round legs crossed. Both were smoking, and they eyed each other furtively, as men of different stamp do when first thrown together. The young artist found his host extremely new and disconcerting; in his presence he felt both shy and awkward. Herr Paul, on the other hand, very much at ease, was thinking indolently:

‘Good-looking young fellow—comes of the people, I expect, not at all the manner of the world; wonder what he talks about.’

Presently noticing that Harz was looking at a photograph, he said: “Ah! yes! that was a woman! They are not to be found in these days. She could dance, the little Coralie! Did you ever see such arms? Confess that she is beautiful, hein?”

“She has individuality,” said Harz. “A fine type!”

Herr Paul blew out a cloud of smoke.

“Yes,” he murmured, “she was fine all over!” He had dropped his eyeglasses, and his full brown eyes, with little crow’s-feet at the corners, wandered from his visitor to his cigar.

‘He’d be like a Satyr if he wasn’t too clean,’ thought Harz. ‘Put vine leaves in his hair, paint him asleep, with his hands crossed, so!’

“When I am told a person has individuality,” Herr Paul was saying in a rich and husky voice, “I generally expect boots that bulge, an umbrella of improper colour; I expect a creature of ‘bad form’ as they say in England; who will shave some days and some days will not shave; who sometimes smells of India-rubber, and sometimes does not smell, which is discouraging!”

“You do not approve of individuality?” said Harz shortly.

“Not if it means doing, and thinking, as those who know better do not do, or think.”

“And who are those who know better?”

“Ah! my dear, you are asking me a riddle? Well, then—Society, men of birth, men of recognised position, men above eccentricity, in a word, of reputation.”

Harz looked at him fixedly. “Men who haven’t the courage of their own ideas, not even the courage to smell of India-rubber; men who have no desires, and so can spend all their time making themselves flat!”

Herr Paul drew out a red silk handkerchief and wiped his beard. “I assure you, my dear,” he said, “it is easier to be flat; it is more respectable to be flat. Himmel! why not, then, be flat?”

“Like any common fellow?”

“Certes; like any common fellow—like me, par exemple!” Herr Paul waved his hand. When he exercised unusual tact, he always made use of a French expression.

Harz flushed. Herr Paul followed up his victory. “Come, come!” he said. “Pass me my men of repute! que diable! we are not anarchists.”

“Are you sure?” said Harz.

Herr Paul twisted his moustache. “I beg your pardon,” he said slowly. But at this moment the door was opened; a rumbling voice remarked: “Morning, Paul. Who’s your visitor?” Harz saw a tall, bulky figure in the doorway.

“Come in,” called out Herr Paul. “Let me present to you a new acquaintance, an artist: Herr Harz—Mr. Nicholas Treffry. Psumm bumm! All this introducing is dry work.” And going to the sideboard he poured out three glasses of a light, foaming beer.

Mr. Treffry waved it from him: “Not for me,” he said: “Wish I could! They won’t let me look at it.” And walking over, to the window with a heavy tread, which trembled like his voice, he sat down. There was something in his gait like the movements of an elephant’s hind legs. He was very tall (it was said, with the customary exaggeration of family tradition, that there never had been a male Treffry under six feet in height), but now he stooped, and had grown stout. There was something at once vast and unobtrusive about his personality.

He wore a loose brown velvet jacket, and waistcoat, cut to show a soft frilled shirt and narrow black ribbon tie; a thin gold chain was looped round his neck and fastened to his fob. His heavy cheeks had folds in them like those in a bloodhound’s face. He wore big, drooping, yellow-grey moustaches, which he had a habit of sucking, and a goatee beard. He had long loose ears that might almost have been said to gap. On his head there was a soft black hat, large in the brim and low in the crown. His grey eyes, heavy-lidded, twinkled under their bushy brows with a queer, kind cynicism. As a young man he had sown many a wild oat; but he had also worked and made money in business; he had, in fact, burned the candle at both ends; but he had never been unready to do his fellows a good turn. He had a passion for driving, and his reckless method of pursuing this art had caused him to be nicknamed: “The notorious Treffry.”

Once, when he was driving tandem down a hill with a loose rein, the friend beside him had said: “For all the good you’re doing with those reins, Treffry, you might as well throw them on the horses’ necks.”

“Just so,” Treffry had answered. At the bottom of the hill they had gone over a wall into a potato patch. Treffry had broken several ribs; his friend had gone unharmed.

He was a great sufferer now, but, constitutionally averse to being pitied, he had a disconcerting way of humming, and this, together with the shake in his voice, and his frequent use of peculiar phrases, made the understanding of his speech depend at times on intuition rather than intelligence.

The clock began to strike eleven. Harz muttered an excuse, shook hands with his host, and bowing to his new acquaintance, went away. He caught a glimpse of Greta’s face against the window, and waved his hand to her. In the road he came on Dawney, who was turning in between the poplars, with thumbs as usual hooked in the armholes of his waistcoat.

“Hallo!” the latter said.

“Doctor!” Harz answered slyly; “the Fates outwitted me, it seems.”

“Serve you right,” said Dawney, “for your confounded egoism! Wait here till I come out, I shan’t be many minutes.”

But Harz went on his way. A cart drawn by cream-coloured oxen was passing slowly towards the bridge. In front of the brushwood piled on it two peasant girls were sitting with their feet on a mat of grass—the picture of contentment.

“I’m wasting my time!” he thought. “I’ve done next to nothing in two months. Better get back to London! That girl will never make a painter!” She would never make a painter, but there was something in her that he could not dismiss so rapidly. She was not exactly beautiful, but she was sympathetic. The brow was pleasing, with dark-brown hair softly turned back, and eyes so straight and shining. The two sisters were very different! The little one was innocent, yet mysterious; the elder seemed as clear as crystal!

He had entered the town, where the arcaded streets exuded their peculiar pungent smell of cows and leather, wood-smoke, wine-casks, and drains. The sound of rapid wheels over the stones made him turn his head. A carriage drawn by red-roan horses was passing at a great pace. People stared at it, standing still, and looking alarmed. It swung from side to side and vanished round a corner. Harz saw Mr. Nicholas Treffry in a long, whitish dust-coat; his Italian servant, perched behind, was holding to the seat-rail, with a nervous grin on his dark face.

‘Certainly,’ Harz thought, ‘there’s no getting away from these people this morning—they are everywhere.’

In his studio he began to sort his sketches, wash his brushes, and drag out things he had accumulated during his two months’ stay. He even began to fold his blanket door. But suddenly he stopped. Those two girls! Why not try? What a picture! The two heads, the sky, and leaves! Begin to-morrow! Against that window—no, better at the Villa! Call the picture—Spring...!

The wind, stirring among trees and bushes, flung the young leaves skywards. The trembling of their silver linings was like the joyful flutter of a heart at good news. It was one of those Spring mornings when everything seems full of a sweet restlessness—soft clouds chasing fast across the sky; soft scents floating forth and dying; the notes of birds, now shrill and sweet, now hushed in silences; all nature striving for something, nothing at peace.

Villa Rubein withstood the influence of the day, and wore its usual look of rest and isolation. Harz sent in his card, and asked to see “der Herr.” The servant, a grey-eyed, clever-looking Swiss with no hair on his face, came back saying:

“Der Herr, mein Herr, is in the Garden gone.” Harz followed him.

Herr Paul, a small white flannel cap on his head, gloves on his hands, and glasses on his nose, was watering a rosebush, and humming the serenade from Faust.

This aspect of the house was very different from the other. The sun fell on it, and over a veranda creepers clung and scrambled in long scrolls. There was a lawn, with freshly mown grass; flower-beds were laid out, and at the end of an avenue of young acacias stood an arbour covered with wisteria.

In the east, mountain peaks—fingers of snow—glittered above the mist. A grave simplicity lay on that scene, on the roofs and spires, the valleys and the dreamy hillsides, with their yellow scars and purple bloom, and white cascades, like tails of grey horses swishing in the wind.

Herr Paul held out his hand: “What can we do for you?” he said.

“I have to beg a favour,” replied Harz. “I wish to paint your daughters. I will bring the canvas here—they shall have no trouble. I would paint them in the garden when they have nothing else to do.”

Herr Paul looked at him dubiously—ever since the previous day he had been thinking: ‘Queer bird, that painter—thinks himself the devil of a swell! Looks a determined fellow too!’ Now—staring in the painter’s face—it seemed to him, on the whole, best if some one else refused this permission.

“With all the pleasure, my dear sir,” he said. “Come, let us ask these two young ladies!” and putting down his hose, he led the way towards the arbour, thinking: ‘You’ll be disappointed, my young conqueror, or I’m mistaken.’

Miss Naylor and the girls were sitting in the shade, reading La Fontaine’s fables. Greta, with one eye on her governess, was stealthily cutting a pig out of orange peel.

“Ah! my dear dears!” began Herr Paul, who in the presence of Miss Naylor always paraded his English. “Here is our friend, who has a very flattering request to make; he would paint you, yes—both together, alfresco, in the air, in the sunshine, with the birds, the little birds!”

Greta, gazing at Harz, gushed deep pink, and furtively showed him her pig.

Christian said: “Paint us? Oh no!”

She saw Harz looking at her, and added, slowly: “If you really wish it, I suppose we could!” then dropped her eyes.

“Ah!” said Herr Paul raising his brows till his glasses fell from his nose: “And what says Gretchen? Does she want to be handed up to posterities a little peacock along with the other little birds?”

Greta, who had continued staring at the painter, said: “Of—course—I—want—to—be.”

“Prrt!” said Herr Paul, looking at Miss Naylor. The little lady indeed opened her mouth wide, but all that came forth was a tiny squeak, as sometimes happens when one is anxious to say something, and has not arranged beforehand what it shall be.

The affair seemed ended; Harz heaved a sigh of satisfaction. But Herr Paul had still a card to play.

“There is your Aunt,” he said; “there are things to be considered—one must certainly inquire—so, we shall see.” Kissing Greta loudly on both cheeks, he went towards the house.

“What makes you want to paint us?” Christian asked, as soon as he was gone.

“I think it very wrong,” Miss Naylor blurted out.

“Why?” said Harz, frowning.

“Greta is so young—there are lessons—it is such a waste of time!”

His eyebrows twitched: “Ah! You think so!”

“I don’t see why it is a waste of time,” said Christian quietly; “there are lots of hours when we sit here and do nothing.”

“And it is very dull,” put in Greta, with a pout.

“You are rude, Greta,” said Miss Naylor in a little rage, pursing her lips, and taking up her knitting.

“I think it seems always rude to speak the truth,” said Greta. Miss Naylor looked at her in that concentrated manner with which she was in the habit of expressing displeasure.

But at this moment a servant came, and said that Mrs. Decie would be glad to see Herr Harz. The painter made them a stiff bow, and followed the servant to the house. Miss Naylor and the two girls watched his progress with apprehensive eyes; it was clear that he had been offended.

Crossing the veranda, and passing through an open window hung with silk curtains, Hart entered a cool dark room. This was Mrs. Decie’s sanctum, where she conducted correspondence, received her visitors, read the latest literature, and sometimes, when she had bad headaches, lay for hours on the sofa, with a fan, and her eyes closed. There was a scent of sandalwood, a suggestion of the East, a kind of mystery, in here, as if things like chairs and tables were not really what they seemed, but something much less commonplace.

The visitor looked twice, to be quite sure of anything; there were many plants, bead curtains, and a deal of silverwork and china.

Mrs. Decie came forward in the slightly rustling silk which—whether in or out of fashion—always accompanied her. A tall woman, over fifty, she moved as if she had been tied together at the knees. Her face was long, with broad brows, from which her sandy-grey hair was severely waved back; she had pale eyes, and a perpetual, pale, enigmatic smile. Her complexion had been ruined by long residence in India, and might unkindly have been called fawn-coloured. She came close to Harz, keeping her eyes on his, with her head bent slightly forward.

“We are so pleased to know you,” she said, speaking in a voice which had lost all ring. “It is charming to find some one in these parts who can help us to remember that there is such a thing as Art. We had Mr. C—-here last autumn, such a charming fellow. He was so interested in the native customs and dresses. You are a subject painter, too, I think? Won’t you sit down?”

She went on for some time, introducing painters’ names, asking questions, skating round the edge of what was personal. And the young man stood before her with a curious little smile fixed on his lips. ‘She wants to know whether I’m worth powder and shot,’ he thought.

“You wish to paint my nieces?” Mrs. Decie said at last, leaning back on her settee.

“I wish to have that honour,” Harz answered with a bow.

“And what sort of picture did you think of?”

“That,” said Harz, “is in the future. I couldn’t tell you.” And he thought: ‘Will she ask me if I get my tints in Paris, like the woman Tramper told me of?’

The perpetual pale smile on Mrs. Decie’s face seemed to invite his confidence, yet to warn him that his words would be sucked in somewhere behind those broad fine brows, and carefully sorted. Mrs. Decie, indeed, was thinking: ‘Interesting young man, regular Bohemian—no harm in that at his age; something Napoleonic in his face; probably has no dress clothes. Yes, should like to see more of him!’ She had a fine eye for points of celebrity; his name was unfamiliar, would probably have been scouted by that famous artist Mr. C—-, but she felt her instinct urging her on to know him. She was, to do her justice, one of those “lion” finders who seek the animal for pleasure, not for the glory it brings them; she had the courage of her instincts—lion-entities were indispensable to her, but she trusted to divination to secure them; nobody could foist a “lion” on her.

“It will be very nice. You will stay and have some lunch? The arrangements here are rather odd. Such a mixed household—but there is always lunch at two o’clock for any one who likes, and we all dine at seven. You would have your sittings in the afternoons, perhaps? I should so like to see your sketches. You are using the old house on the wall for studio; that is so original of you!”

Harz would not stay to lunch, but asked if he might begin work that afternoon; he left a little suffocated by the sandalwood and sympathy of this sphinx-like woman.

Walking home along the river wall, with the singing of the larks and thrushes, the rush of waters, the humming of the chafers in his ears, he felt that he would make something fine of this subject. Before his eyes the faces of the two girls continually started up, framed by the sky, with young leaves guttering against their cheeks.

Three days had passed since Harz began his picture, when early in the morning, Greta came from Villa Rubein along the river dyke and sat down on a bench from which the old house on the wall was visible. She had not been there long before Harz came out.

“I did not knock,” said Greta, “because you would not have heard, and it is so early, so I have been waiting for you a quarter of an hour.”

Selecting a rosebud, from some flowers in her hand, she handed it to him. “That is my first rosebud this year,” she said; “it is for you because you are painting me. To-day I am thirteen, Herr Harz; there is not to be a sitting, because it is my birthday; but, instead, we are all going to Meran to see the play of Andreas Hofer. You are to come too, please; I am here to tell you, and the others shall be here directly.”

Harz bowed: “And who are the others?”

“Christian, and Dr. Edmund, Miss Naylor, and Cousin Teresa. Her husband is ill, so she is sad, but to-day she is going to forget that. It is not good to be always sad, is it, Herr Harz?”

He laughed: “You could not be.”

Greta answered gravely: “Oh yes, I could. I too am often sad. You are making fun. You are not to make fun to-day, because it is my birthday. Do you think growing up is nice, Herr Harz?”

“No, Fraulein Greta, it is better to have all the time before you.”

They walked on side by side.

“I think,” said Greta, “you are very much afraid of losing time. Chris says that time is nothing.”

“Time is everything,” responded Harz.

“She says that time is nothing, and thought is everything,” Greta murmured, rubbing a rose against her cheek, “but I think you cannot have a thought unless you have the time to think it in. There are the others! Look!”

A cluster of sunshades on the bridge glowed for a moment and was lost in shadow.

“Come,” said Harz, “let’s join them!”

At Meran, under Schloss Tirol, people were streaming across the meadows into the open theatre. Here were tall fellows in mountain dress, with leather breeches, bare knees, and hats with eagles’ feathers; here were fruit-sellers, burghers and their wives, mountebanks, actors, and every kind of visitor. The audience, packed into an enclosure of high boards, sweltered under the burning sun. Cousin Teresa, tall and thin, with hard, red cheeks, shaded her pleasant eyes with her hand.

The play began. It depicted the rising in the Tyrol of 1809: the village life, dances and yodelling; murmurings and exhortations, the warning beat of drums; then the gathering, with flintlocks, pitchforks, knives; the battle and victory; the homecoming, and festival. Then the second gathering, the roar of cannon; betrayal, capture, death. The impassive figure of the patriot Andreas Hofer always in front, black-bearded, leathern-girdled, under the blue sky, against a screen of mountains.

Harz and Christian sat behind the others. He seemed so intent on the play that she did not speak, but watched his face, rigid with a kind of cold excitement; he seemed to be transported by the life passing before them. Something of his feeling seized on her; when the play was over she too was trembling. In pushing their way out they became separated from the others.

“There’s a short cut to the station here,” said Christian; “let’s go this way.”

The path rose a little; a narrow stream crept alongside the meadow, and the hedge was spangled with wild roses. Christian kept glancing shyly at the painter. Since their meeting on the river wall her thoughts had never been at rest. This stranger, with his keen face, insistent eyes, and ceaseless energy, had roused a strange feeling in her; his words had put shape to something in her not yet expressed. She stood aside at a stile to make way for some peasant boys, dusty and rough-haired, who sang and whistled as they went by.

“I was like those boys once,” said Harz.

Christian turned to him quickly. “Ah! that was why you felt the play, so much.”

“It’s my country up there. I was born amongst the mountains. I looked after the cows, and slept in hay-cocks, and cut the trees in winter. They used to call me a ‘black sheep,’ a ‘loafer’ in my village.”

“Why?”

“Ah! why? I worked as hard as any of them. But I wanted to get away. Do you think I could have stayed there all my life?”

Christian’s eyes grew eager.

“If people don’t understand what it is you want to do, they always call you a loafer!” muttered Harz.

“But you did what you meant to do in spite of them,” Christian said.

For herself it was so hard to finish or decide. When in the old days she told Greta stories, the latter, whose instinct was always for the definite, would say: “And what came at the end, Chris? Do finish it this morning!” but Christian never could. Her thoughts were deep, vague, dreamy, invaded by both sides of every question. Whatever she did, her needlework, her verse-making, her painting, all had its charm; but it was not always what it was intended for at the beginning. Nicholas Treffry had once said of her: “When Chris starts out to make a hat, it may turn out an altar-cloth, but you may bet it won’t be a hat.” It was her instinct to look for what things meant; and this took more than all her time. She knew herself better than most girls of nineteen, but it was her reason that had informed her, not her feelings. In her sheltered life, her heart had never been ruffled except by rare fits of passion—“tantrums” old Nicholas Treffry dubbed them—at what seemed to her mean or unjust.

“If I were a man,” she said, “and going to be great, I should have wanted to begin at the very bottom as you did.”

“Yes,” said Harz quickly, “one should be able to feel everything.”

She did not notice how simply he assumed that he was going to be great. He went on, a smile twisting his mouth unpleasantly beneath its dark moustache—“Not many people think like you! It’s a crime not to have been born a gentleman.”

“That’s a sneer,” said Christian; “I didn’t think you would have sneered!”

“It is true. What is the use of pretending that it isn’t?”

“It may be true, but it is finer not to say it!”

“By Heavens!” said Harz, striking one hand into the other, “if more truth were spoken there would not be so many shams.”

Christian looked down at him from her seat on the stile.

“You are right all the same, Fraulein Christian,” he added suddenly; “that’s a very little business. Work is what matters, and trying to see the beauty in the world.”

Christian’s face changed. She understood, well enough, this craving after beauty. Slipping down from the stile, she drew a slow deep breath.

“Yes!” she said. Neither spoke for some time, then Harz said shyly:

“If you and Fraulein Greta would ever like to come and see my studio, I should be so happy. I would try and clean it up for you!”

“I should like to come. I could learn something. I want to learn.”

They were both silent till the path joined the road.

“We must be in front of the others; it’s nice to be in front—let’s dawdle. I forgot—you never dawdle, Herr Harz.”

“After a big fit of work, I can dawdle against any one; then I get another fit of work—it’s like appetite.”

“I’m always dawdling,” answered Christian.

By the roadside a peasant woman screwed up her sun-dried face, saying in a low voice: “Please, gracious lady, help me to lift this basket!”

Christian stooped, but before she could raise it, Harz hoisted it up on his back.

“All right,” he nodded; “this good lady doesn’t mind.”

The woman, looking very much ashamed, walked along by Christian; she kept rubbing her brown hands together, and saying; “Gracious lady, I would not have wished. It is heavy, but I would not have wished.”

“I’m sure he’d rather carry it,” said Christian.

They had not gone far along the road, however, before the others passed them in a carriage, and at the strange sight Miss Naylor could be seen pursing her lips; Cousin Teresa nodding pleasantly; a smile on Dawney’s face; and beside him Greta, very demure. Harz began to laugh.

“What are you laughing at?” asked Christian.

“You English are so funny. You mustn’t do this here, you mustn’t do that there, it’s like sitting in a field of nettles. If I were to walk with you without my coat, that little lady would fall off her seat.” His laugh infected Christian; they reached the station feeling that they knew each other better.

The sun had dipped behind the mountains when the little train steamed down the valley. All were subdued, and Greta, with a nodding head, slept fitfully. Christian, in her corner, was looking out of the window, and Harz kept studying her profile.

He tried to see her eyes. He had remarked indeed that, whatever their expression, the brows, arched and rather wide apart, gave them a peculiar look of understanding. He thought of his picture. There was nothing in her face to seize on, it was too sympathetic, too much like light. Yet her chin was firm, almost obstinate.

The train stopped with a jerk; she looked round at him. It was as though she had said: “You are my friend.”

At Villa Rubein, Herr Paul had killed the fatted calf for Greta’s Fest. When the whole party were assembled, he alone remained standing; and waving his arm above the cloth, cried: “My dears! Your happiness! There are good things here—Come!” And with a sly look, the air of a conjurer producing rabbits, he whipped the cover off the soup tureen:

“Soup-turtle, fat, green fat!” He smacked his lips.

No servants were allowed, because, as Greta said to Harz:

“It is that we are to be glad this evening.”

Geniality radiated from Herr Paul’s countenance, mellow as a bowl of wine. He toasted everybody, exhorting them to pleasure.

Harz passed a cracker secretly behind Greta’s head, and Miss Naylor, moved by a mysterious impulse, pulled it with a sort of gleeful horror; it exploded, and Greta sprang off her chair. Scruff, seeing this, appeared suddenly on the sideboard with his forelegs in a plate of soup; without moving them, he turned his head, and appeared to accuse the company of his false position. It was the signal for shrieks of laughter. Scruff made no attempt to free his forelegs; but sniffed the soup, and finding that nothing happened, began to lap it.

“Take him out! Oh! take him out!” wailed Greta, “he shall be ill!”

“Allons! Mon cher!” cried Herr Paul, “c’est magnifique, mais, vous savez, ce nest guere la guerre!” Scruff, with a wild spring, leaped past him to the ground.

“Ah!” cried Miss Naylor, “the carpet!” Fresh moans of mirth shook the table; for having tasted the wine of laughter, all wanted as much more as they could get. When Scruff and his traces were effaced, Herr Paul took a ladle in his hand.

“I have a toast,” he said, waving it for silence; “a toast we will drink all together from our hearts; the toast of my little daughter, who to-day has thirteen years become; and there is also in our hearts,” he continued, putting down the ladle and suddenly becoming grave, “the thought of one who is not today with us to see this joyful occasion; to her, too, in this our happiness we turn our hearts and glasses because it is her joy that we should yet be joyful. I drink to my little daughter; may God her shadow bless!”

All stood up, clinking their glasses, and drank: then, in the hush that followed, Greta, according to custom, began to sing a German carol; at the end of the fourth line she stopped, abashed.

Heir Paul blew his nose loudly, and, taking up a cap that had fallen from a cracker, put it on.

Every one followed his example, Miss Naylor attaining the distinction of a pair of donkey’s ears, which she wore, after another glass of wine, with an air of sacrificing to the public good.

At the end of supper came the moment for the offering of gifts. Herr Paul had tied a handkerchief over Greta’s eyes, and one by one they brought her presents. Greta, under forfeit of a kiss, was bound to tell the giver by the feel of the gift. Her swift, supple little hands explored noiselessly; and in every case she guessed right.

Dawney’s present, a kitten, made a scene by clawing at her hair.

“That is Dr. Edmund’s,” she cried at once. Christian saw that Harz had disappeared, but suddenly he came back breathless, and took his place at the end of the rank of givers.

Advancing on tiptoe, he put his present into Greta’s hands. It was a small bronze copy of a Donatello statue.

“Oh, Herr Harz!” cried Greta; “I saw it in the studio that day. It stood on the table, and it is lovely.”

Mrs. Decie, thrusting her pale eyes close to it, murmured: “Charming!”

Mr. Treffry took it in his fingers.

“Rum little toad! Cost a pot of money, I expect!” He eyed Harz doubtfully.

They went into the next room now, and Herr Paul, taking Greta’s bandage, transferred it to his own eyes.

“Take care—take care, all!” he cried; “I am a devil of a catcher,” and, feeling the air cautiously, he moved forward like a bear about to hug. He caught no one. Christian and Greta whisked under his arms and left him grasping at the air. Mrs. Decie slipped past with astonishing agility. Mr. Treffry, smoking his cigar, and barricaded in a corner, jeered: “Bravo, Paul! The active beggar! Can’t he run! Go it, Greta!”

At last Herr Paul caught Cousin Teresa, who, fattened against the wall, lost her head, and stood uttering tiny shrieks.

Suddenly Mrs. Decie started playing The Blue Danube. Herr Paul dropped the handkerchief, twisted his moustache up fiercely, glared round the room, and seizing Greta by the waist, began dancing furiously, bobbing up and down like a cork in lumpy water. Cousin Teresa followed suit with Miss Naylor, both very solemn, and dancing quite different steps. Harz, went up to Christian.

“I can’t dance,” he said, “that is, I have only danced once, but—if you would try with me!”

She put her hand on his arm, and they began. She danced, light as a feather, eyes shining, feet flying, her body bent a little forward. It was not a great success at first, but as soon as the time had got into Harz’s feet, they went swinging on when all the rest had stopped. Sometimes one couple or another slipped through the window to dance on the veranda, and came whirling in again. The lamplight glowed on the girls’ white dresses; on Herr Paul’s perspiring face. He constituted in himself a perfect orgy, and when the music stopped flung himself, full length, on the sofa gasping out:

“My God! But, my God!”

Suddenly Christian felt Harz cling to her arm.

Glowing and panting she looked at him.

“Giddy!” he murmured: “I dance so badly; but I’ll soon learn.”

Greta clapped her hands: “Every evening we will dance, every evening we will dance.”

Harz looked at Christian; the colour had deepened in her face.

“I’ll show you how they dance in my village, feet upon the ceiling!” And running to Dawney, he said:

“Hold me here! Lift me—so! Now, on—two,” he tried to swing his feet above his head, but, with an “Ouch!” from Dawney, they collapsed, and sat abruptly on the floor. This untimely event brought the evening to an end. Dawney left, escorting Cousin Teresa, and Harz strode home humming The Blue Danube, still feeling Christian’s waist against his arm.

In their room the two girls sat long at the window to cool themselves before undressing.

“Ah!” sighed Greta, “this is the happiest birthday I have had.”

Cristian too thought: ‘I have never been so happy in my life as I have been to-day. I should like every day to be like this!’ And she leant out into the night, to let the air cool her cheeks.

“Chris!” said Greta some days after this, “Miss Naylor danced last evening; I think she shall have a headache to-day. There is my French and my history this morning.”

“Well, I can take them.”

“That is nice; then we can talk. I am sorry about the headache. I shall give her some of my Eau de Cologne.”

Miss Naylor’s headaches after dancing were things on which to calculate. The girls carried their books into the arbour; it was a showery day, and they had to run for shelter through the raindrops and sunlight.

“The French first, Chris!” Greta liked her French, in which she was not far inferior to Christian; the lesson therefore proceeded in an admirable fashion. After one hour exactly by her watch (Mr. Treffry’s birthday present loved and admired at least once every hour) Greta rose.

“Chris, I have not fed my rabbits.”

“Be quick! there’s not much time for history.”

Greta vanished. Christian watched the bright water dripping from the roof; her lips were parted in a smile. She was thinking of something Harz had said the night before. A discussion having been started as to whether average opinion did, or did not, safeguard Society, Harz, after sitting silent, had burst out: “I think one man in earnest is better than twenty half-hearted men who follow tamely; in the end he does Society most good.”

Dawney had answered: “If you had your way there would be no Society.”

“I hate Society because it lives upon the weak.”

“Bah!” Herr Paul chimed in; “the weak goes to the wall; that is as certain as that you and I are here.”

“Let them fall against the wall,” cried Harz; “don’t push them there....”

Greta reappeared, walking pensively in the rain.

“Bino,” she said, sighing, “has eaten too much. I remember now, I did feed them before. Must we do the history, Chris?”

“Of course!”

Greta opened her book, and put a finger in the page. “Herr Harz is very kind to me,” she said. “Yesterday he brought a bird which had come into his studio with a hurt wing; he brought it very gently in his handkerchief—he is very kind, the bird was not even frightened of him. You did not know about that, Chris?”

Chris flushed a little, and said in a hurt voice

“I don’t see what it has to—do with me.”

“No,” assented Greta.

Christian’s colour deepened. “Go on with your history, Greta.”

“Only,” pursued Greta, “that he always tells you all about things, Chris.”

“He doesn’t! How can you say that!”

“I think he does, and it is because you do not make him angry. It is very easy to make him angry; you have only to think differently, and he shall be angry at once.”

“You are a little cat!” said Christian; “it isn’t true, at all. He hates shams, and can’t bear meanness; and it is mean to cover up dislikes and pretend that you agree with people.”

“Papa says that he thinks too much about himself.”

“Father!” began Christian hotly; biting her lips she stopped, and turned her wrathful eyes on Greta.

“You do not always show your dislikes, Chris.”

“I? What has that to do with it? Because one is a coward that doesn’t make it any better, does it?”

“I think that he has a great many dislikes,” murmured Greta.

“I wish you would attend to your own faults, and not pry into other people’s,” and pushing the book aside, Christian gazed in front of her.

Some minutes passed, then Greta leaning over, rubbed a cheek against her shoulder.

“I am very sorry, Chris—I only wanted to be talking. Shall I read some history?”

“Yes,” said Christian coldly.

“Are you angry with me, Chris?”

There was no answer. The lingering raindrops pattered down on the roof. Greta pulled at her sister’s sleeve.

“Look, Chris!” she said. “There is Herr Harz!”

Christian looked up, dropped her eyes again, and said: “Will you go on with the history, Greta?”

Greta sighed.

“Yes, I will—but, oh! Chris, there is the luncheon gong!” and she meekly closed the book.

During the following weeks there was a “sitting” nearly every afternoon. Miss Naylor usually attended them; the little lady was, to a certain extent, carried past objection. She had begun to take an interest in the picture, and to watch the process out of the corner of her eye; in the depths of her dear mind, however, she never quite got used to the vanity and waste of time; her lips would move and her knitting-needles click in suppressed remonstrances.

What Harz did fast he did best; if he had leisure he “saw too much,” loving his work so passionately that he could never tell exactly when to stop. He hated to lay things aside, always thinking: “I can get it better.” Greta was finished, but with Christian, try as he would, he was not satisfied; from day to day her face seemed to him to change, as if her soul were growing.

There were things too in her eyes that he could neither read nor reproduce.

Dawney would often stroll out to them after his daily visit, and lying on the grass, his arms crossed behind his head, and a big cigar between his lips, would gently banter everybody. Tea came at five o’clock, and then Mrs. Decie appeared armed with a magazine or novel, for she was proud of her literary knowledge. The sitting was suspended; Harz, with a cigarette, would move between the table and the picture, drinking his tea, putting a touch in here and there; he never sat down till it was all over for the day. During these “rests” there was talk, usually ending in discussion. Mrs. Decie was happiest in conversations of a literary order, making frequent use of such expressions as: “After all, it produces an illusion—does anything else matter?” “Rather a poseur, is he not?” “A question, that, of temperament,” or “A matter of the definition of words”; and other charming generalities, which sound well, and seem to go far, and are pleasingly irrefutable. Sometimes the discussion turned on Art—on points of colour or technique; whether realism was quite justified; and should we be pre-Raphaelites? When these discussions started, Christian’s eyes would grow bigger and clearer, with a sort of shining reasonableness; as though they were trying to see into the depths. And Harz would stare at them. But the look in those eyes eluded him, as if they had no more meaning than Mrs. Decie’s, which, with their pale, watchful smile, always seemed saying: “Come, let us take a little intellectual exercise.”

Greta, pulling Scruff’s ears, would gaze up at the speakers; when the talk was over, she always shook herself. But if no one came to the “sittings,” there would sometimes be very earnest, quick talk, sometimes long silences.

One day Christian said: “What is your religion?”

Harz finished the touch he was putting on the canvas, before he answered: “Roman Catholic, I suppose; I was baptised in that Church.”

“I didn’t mean that. Do you believe in a future life?”

“Christian,” murmured Greta, who was plaiting blades of grass, “shall always want to know what people think about a future life; that is so funny!”

“How can I tell?” said Harz; “I’ve never really thought of it—never had the time.”

“How can you help thinking?” Christian said: “I have to—it seems to me so awful that we might come to an end.”

She closed her book, and it slipped off her lap. She went on: “There must be a future life, we’re so incomplete. What’s the good of your work, for instance? What’s the use of developing if you have to stop?”

“I don’t know,” answered Harz. “I don’t much care. All I know is, I’ve got to work.”

“But why?”

“For happiness—the real happiness is fighting—the rest is nothing. If you have finished a thing, does it ever satisfy you? You look forward to the next thing at once; to wait is wretched!”

Christian clasped her hands behind her neck; sunlight flickered through the leaves on to the bosom of her dress.

“Ah! Stay like that!” cried Harz.

She let her eyes rest on his face, swinging her foot a little.

“You work because you must; but that’s not enough. Why do you feel you must? I want to know what’s behind. When I was travelling with Aunt Constance the winter before last we often talked—I’ve heard her discuss it with her friends. She says we move in circles till we reach Nirvana. But last winter I found I couldn’t talk to her; it seemed as if she never really meant anything. Then I started reading—Kant and Hegel—”

“Ah!” put in Harz, “if they would teach me to draw better, or to see a new colour in a flower, or an expression in a face, I would read them all.”

Christian leaned forward: “It must be right to get as near truth as possible; every step gained is something. You believe in truth; truth is the same as beauty—that was what you said—you try to paint the truth, you always see the beauty. But how can we know truth, unless we know what is at the root of it?”

“I—think,” murmured Greta, sotto voce, “you see one way—and he sees another—because—you are not one person.”

“Of course!” said Christian impatiently, “but why—”

A sound of humming interrupted her.

Nicholas Treffry was coming from the house, holding the Times in one hand, and a huge meerschaum pipe in the other.

“Aha!” he said to Harz: “how goes the picture?” and he lowered himself into a chair.

“Better to-day, Uncle?” said Christian softly.

Mr. Treffry growled. “Confounded humbugs, doctors!” he said. “Your father used to swear by them; why, his doctor killed him—made him drink such a lot of stuff!”

“Why then do you have a doctor, Uncle Nic?” asked Greta.

Mr. Treffry looked at her; his eyes twinkled. “I don’t know, my dear. If they get half a chance, they won’t let go of you!”

There had been a gentle breeze all day, but now it had died away; not a leaf quivered, not a blade of grass was stirring; from the house were heard faint sounds as of some one playing on a pipe. A blackbird came hopping down the path.

“When you were a boy, did you go after birds’ nests, Uncle Nic?” Greta whispered.

“I believe you, Greta.” The blackbird hopped into the shrubbery.

“You frightened him, Uncle Nic! Papa says that at Schloss Konig, where he lived when he was young, he would always be after jackdaws’ nests.”

“Gammon, Greta. Your father never took a jackdaw’s nest, his legs are much too round!”

“Are you fond of birds, Uncle Nic?”

“Ask me another, Greta! Well, I s’pose so.”

“Then why did you go bird-nesting? I think it is cruel”

Mr. Treffry coughed behind his paper: “There you have me, Greta,” he remarked.

Harz began to gather his brushes: “Thank you,” he said, “that’s all I can do to-day.”

“Can I look?” Mr. Treffry inquired.

“Certainly!”

Uncle Nic got up slowly, and stood in front of the picture. “When it’s for sale,” he said at last, “I’ll buy it.”

Harz bowed; but for some reason he felt annoyed, as if he had been asked to part with something personal.

“I thank you,” he said. A gong sounded.

“You’ll stay and have a snack with us?” said Mr. Treffry; “the doctor’s stopping.” Gathering up his paper, he moved off to the house with his hand on Greta’s shoulder, the terrier running in front. Harz and Christian were left alone. He was scraping his palette, and she was sitting with her elbows resting on her knees; between them, a gleam of sunlight dyed the path golden. It was evening already; the bushes and the flowers, after the day’s heat, were breathing out perfume; the birds had started their evensong.

“Are you tired of sitting for your portrait, Fraulein Christian?”

Christian shook her head.

“I shall get something into it that everybody does not see—something behind the surface, that will last.”

Christian said slowly: “That’s like a challenge. You were right when you said fighting is happiness—for yourself, but not for me. I’m a coward. I hate to hurt people, I like them to like me. If you had to do anything that would make them hate you, you would do it all the same, if it helped your work; that’s fine—it’s what I can’t do. It’s—it’s everything. Do you like Uncle Nic?”

The young painter looked towards the house, where under the veranda old Nicholas Treffry was still in sight; a smile came on his lips.

“If I were the finest painter in the world, he wouldn’t think anything of me for it, I’m afraid; but if I could show him handfuls of big cheques for bad pictures I had painted, he would respect me.”

She smiled, and said: “I love him.”

“Then I shall like him,” Harz answered simply.

She put her hand out, and her fingers met his. “We shall be late,” she said, glowing, and catching up her book: “I’m always late!”

There was one other guest at dinner, a well-groomed person with pale, fattish face, dark eyes, and hair thin on the temples, whose clothes had a military cut. He looked like a man fond of ease, who had gone out of his groove, and collided with life. Herr Paul introduced him as Count Mario Sarelli.

Two hanging lamps with crimson shades threw a rosy light over the table, where, in the centre stood a silver basket, full of irises. Through the open windows the garden was all clusters of black foliage in the dying light. Moths fluttered round the lamps; Greta, following them with her eyes, gave quite audible sighs of pleasure when they escaped. Both girls wore white, and Harz, who sat opposite Christian, kept looking at her, and wondering why he had not painted her in that dress.

Mrs. Decie understood the art of dining—the dinner, ordered by Herr Paul, was admirable; the servants silent as their shadows; there was always a hum of conversation.

Sarelli, who sat on her right hand, seemed to partake of little except olives, which he dipped into a glass of sherry. He turned his black, solemn eyes silently from face to face, now and then asking the meaning of an English word. After a discussion on modern Rome, it was debated whether or no a criminal could be told by the expression of his face.

“Crime,” said Mrs. Decie, passing her hand across her brow—“crime is but the hallmark of strong individuality.”