ODD CRAFT

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: Project Gutenberg, Odd Craft, by W.W. Jacobs

Author: W.W. Jacobs

Release Date: October 30, 2006 [EBook #12215]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ODD CRAFT, COMPLETE ***

Produced by David Widger.

――――

CONTENTS

――――

――――

THE MONEY-BOX

Sailormen are not good ‘ands at saving money as a rule, said the night-watchman, as he wistfully toyed with a bad shilling on his watch-chain, though to ‘ear ‘em talk of saving when they’re at sea and there isn’t a pub within a thousand miles of ‘em, you might think different.

It ain’t for the want of trying either with some of ‘em, and I’ve known men do all sorts o’ things as soon as they was paid off, with a view to saving. I knew one man as used to keep all but a shilling or two in a belt next to ‘is skin so that he couldn’t get at it easy, but it was all no good. He was always running short in the most inconvenient places. I’ve seen ‘im wriggle for five minutes right off, with a tramcar conductor standing over ‘im and the other people in the tram reading their papers with one eye and watching him with the other.

Ginger Dick and Peter Russet—two men I’ve spoke of to you afore—tried to save their money once. They’d got so sick and tired of spending it all in p’r’aps a week or ten days arter coming ashore, and ‘aving to go to sea agin sooner than they ‘ad intended, that they determined some way or other to ‘ave things different.

They was homeward bound on a steamer from Melbourne when they made their minds up; and Isaac Lunn, the oldest fireman aboard—a very steady old teetotaler—gave them a lot of good advice about it. They all wanted to rejoin the ship when she sailed agin, and ‘e offered to take a room ashore with them and mind their money, giving ‘em what ‘e called a moderate amount each day.

They would ha’ laughed at any other man, but they knew that old Isaac was as honest as could be and that their money would be safe with ‘im, and at last, after a lot of palaver, they wrote out a paper saying as they were willing for ‘im to ‘ave their money and give it to ‘em bit by bit, till they went to sea agin.

Anybody but Ginger Dick and Peter Russet or a fool would ha’ known better than to do such a thing, but old Isaac ‘ad got such a oily tongue and seemed so fair-minded about wot ‘e called moderate drinking that they never thought wot they was letting themselves in for, and when they took their pay—close on sixteen pounds each—they put the odd change in their pockets and ‘anded the rest over to him.

The first day they was as pleased as Punch. Old Isaac got a nice, respectable bedroom for them all, and arter they’d ‘ad a few drinks they humoured ‘im by ‘aving a nice ‘ot cup o’ tea, and then goin’ off with ‘im to see a magic-lantern performance.

It was called “The Drunkard’s Downfall,” and it begun with a young man going into a nice-looking pub and being served by a nice-looking barmaid with a glass of ale. Then it got on to ‘arf pints and pints in the next picture, and arter Ginger ‘ad seen the lost young man put away six pints in about ‘arf a minute, ‘e got such a raging thirst on ‘im that ‘e couldn’t sit still, and ‘e whispered to Peter Russet to go out with ‘im.

“You’ll lose the best of it if you go now,” ses old Isaac, in a whisper; “in the next picture there’s little frogs and devils sitting on the edge of the pot as ‘e goes to drink.”

“Ginger Dick got up and nodded to Peter.”

“Arter that ‘e kills ‘is mother with a razor,” ses old Isaac, pleading with ‘im and ‘olding on to ‘is coat.

Ginger Dick sat down agin, and when the murder was over ‘e said it made ‘im feel faint, and ‘im and Peter Russet went out for a breath of fresh air. They ‘ad three at the first place, and then they moved on to another and forgot all about Isaac and the dissolving views until ten o’clock, when Ginger, who ‘ad been very liberal to some friends ‘e’d made in a pub, found ‘e’d spent ‘is last penny.

“This comes o’ listening to a parcel o’ teetotalers,” ‘e ses, very cross, when ‘e found that Peter ‘ad spent all ‘is money too. “Here we are just beginning the evening and not a farthing in our pockets.”

They went off ‘ome in a very bad temper. Old Isaac was asleep in ‘is bed, and when they woke ‘im up and said that they was going to take charge of their money themselves ‘e kept dropping off to sleep agin and snoring that ‘ard they could scarcely hear themselves speak. Then Peter tipped Ginger a wink and pointed to Isaac’s trousers, which were ‘anging over the foot of the bed.

Ginger Dick smiled and took ‘em up softly, and Peter Russet smiled too; but ‘e wasn’t best pleased to see old Isaac a-smiling in ‘is sleep, as though ‘e was ‘aving amusing dreams. All Ginger found was a ha’-penny, a bunch o’ keys, and a cough lozenge. In the coat and waistcoat ‘e found a few tracks folded up, a broken pen-knife, a ball of string, and some other rubbish. Then ‘e set down on the foot o’ their bed and made eyes over at Peter.

“Wake ‘im up agin,” ses Peter, in a temper.

Ginger Dick got up and, leaning over the bed, took old Isaac by the shoulders and shook ‘im as if ‘e’d been a bottle o’ medicine.

“Time to get up, lads?” ses old Isaac, putting one leg out o’ bed.

“No, it ain’t,” ses Ginger, very rough; “we ain’t been to bed yet. We want our money back.”

Isaac drew ‘is leg back into bed agin. “Goo’ night,” he ses, and fell fast asleep.

“He’s shamming, that’s wot ‘e is,” ses Peter Russet. “Let’s look for it. It must be in the room somewhere.”

They turned the room upside down pretty near, and then Ginger Dick struck a match and looked up the chimney, but all ‘e found was that it ‘adn’t been swept for about twenty years, and wot with temper and soot ‘e looked so frightful that Peter was arf afraid of ‘im.

“I’ve ‘ad enough of this,” ses Ginger, running up to the bed and ‘olding his sooty fist under old Isaac’s nose. “Now, then, where’s that money? If you don’t give us our money, our ‘ard-earned money, inside o’ two minutes, I’ll break every bone in your body.”

“This is wot comes o’ trying to do you a favour, Ginger,” ses the old man, reproachfully.

“Don’t talk to me,” ses Ginger, “cos I won’t have it. Come on; where is it?”

Old Isaac looked at ‘im, and then he gave a sigh and got up and put on ‘is boots and ‘is trousers.

“I thought I should ‘ave a little trouble with you,” he ses, slowly, “but I was prepared for that.”

“You’ll ‘ave more if you don’t hurry up,” ses Ginger, glaring at ‘im.

“We don’t want to ‘urt you, Isaac,” ses Peter Russet, “we on’y want our money.”

“I know that,” ses Isaac; “you keep still, Peter, and see fair-play, and I’ll knock you silly arterwards.”

He pushed some o’ the things into a corner and then ‘e spat on ‘is ‘ands, and began to prance up and down, and duck ‘is ‘ead about and hit the air in a way that surprised ‘em.

“I ain’t hit a man for five years,” ‘e ses, still dancing up and down— “fighting’s sinful except in a good cause—but afore I got a new ‘art, Ginger, I’d lick three men like you afore breakfast, just to git up a appetite.”

“Look, ‘ere,” ses Ginger; “you’re an old man and I don’t want to ‘urt you; tell us where our money is, our ‘ard-earned money, and I won’t lay a finger on you.”

“I’m taking care of it for you,” ses the old man.

Ginger Dick gave a howl and rushed at him, and the next moment Isaac’s fist shot out and give ‘im a drive that sent ‘im spinning across the room until ‘e fell in a heap in the fireplace. It was like a kick from a ‘orse, and Peter looked very serious as ‘e picked ‘im up and dusted ‘im down.

“You should keep your eye on ‘is fist,” he ses, sharply.

It was a silly thing to say, seeing that that was just wot ‘ad ‘appened, and Ginger told ‘im wot ‘e’d do for ‘im when ‘e’d finished with Isaac. He went at the old man agin, but ‘e never ‘ad a chance, and in about three minutes ‘e was very glad to let Peter ‘elp ‘im into bed.

“It’s your turn to fight him now, Peter,” he ses. “Just move this piller so as I can see.”

“Come on, lad,” ses the old man.

Peter shook ‘is ‘ead. “I have no wish to ‘urt you, Isaac,” he ses, kindly; “excitement like fighting is dangerous for an old man. Give us our money and we’ll say no more about it.”

“No, my lads,” ses Isaac. “I’ve undertook to take charge o’ this money and I’m going to do it; and I ‘ope that when we all sign on aboard the Planet there’ll be a matter o’ twelve pounds each left. Now, I don’t want to be ‘arsh with you, but I’m going back to bed, and if I ‘ave to get up and dress agin you’ll wish yourselves dead.”

He went back to bed agin, and Peter, taking no notice of Ginger Dick, who kept calling ‘im a coward, got into bed alongside of Ginger and fell fast asleep.

They all ‘ad breakfast in a coffee-shop next morning, and arter it was over Ginger, who ‘adn’t spoke a word till then, said that ‘e and Peter Russet wanted a little money to go on with. He said they preferred to get their meals alone, as Isaac’s face took their appetite away.

“Very good,” ses the old man. “I don’t want to force my company on nobody,” and after thinking ‘ard for a minute or two he put ‘is ‘and in ‘is trouser-pocket and gave them eighteen-pence each.

“That’s your day’s allowance,” ses Isaac, “and it’s plenty. There’s ninepence for your dinner, fourpence for your tea, and twopence for a crust o’ bread and cheese for supper. And if you must go and drown yourselves in beer, that leaves threepence each to go and do it with.”

Ginger tried to speak to ‘im, but ‘is feelings was too much for ‘im, and ‘e couldn’t. Then Peter Russet swallered something ‘e was going to say and asked old Isaac very perlite to make it a quid for ‘im because he was going down to Colchester to see ‘is mother, and ‘e didn’t want to go empty-’anded.

“You’re a good son, Peter,” ses old Isaac, “and I wish there was more like you. I’ll come down with you, if you like; I’ve got nothing to do.”

Peter said it was very kind of ‘im, but ‘e’d sooner go alone, owing to his mother being very shy afore strangers.

“Well, I’ll come down to the station and take a ticket for you,” ses Isaac.

Then Peter lost ‘is temper altogether, and banged ‘is fist on the table and smashed ‘arf the crockery. He asked Isaac whether ‘e thought ‘im and Ginger Dick was a couple o’ children, and ‘e said if ‘e didn’t give ‘em all their money right away ‘e’d give ‘im in charge to the first policeman they met.

“I’m afraid you didn’t intend for to go and see your mother, Peter,” ses the old man.

“Look ‘ere,” ses Peter, “are you going to give us that money?”

“Not if you went down on your bended knees,” ses the old man.

“Very good,” says Peter, getting up and walking outside; “then come along o’ me to find a police-man.”

“I’m agreeable,” ses Isaac, “but I’ve got the paper you signed.”

Peter said ‘e didn’t care twopence if ‘e’d got fifty papers, and they walked along looking for a police-man, which was a very unusual thing for them to do.

“I ‘ope for your sakes it won’t be the same police-man that you and Ginger Dick set on in Gun Alley the night afore you shipped on the Planet,” ses Isaac, pursing up ‘is lips.

“‘Tain’t likely to be,” ses Peter, beginning to wish ‘e ‘adn’t been so free with ‘is tongue.

“Still, if I tell ‘im, I dessay he’ll soon find ‘im,” ses Isaac; “there’s one coming along now, Peter; shall I stop ‘im?”

Peter Russet looked at ‘im and then he looked at Ginger, and they walked by grinding their teeth. They stuck to Isaac all day, trying to get their money out of ‘im, and the names they called ‘im was a surprise even to themselves. And at night they turned the room topsy-turvy agin looking for their money and ‘ad more unpleasantness when they wanted Isaac to get up and let ‘em search the bed.

They ‘ad breakfast together agin next morning and Ginger tried another tack. He spoke quite nice to Isaac, and ‘ad three large cups o’ tea to show ‘im ‘ow ‘e was beginning to like it, and when the old man gave ‘em their eighteen-pences ‘e smiled and said ‘e’d like a few shillings extra that day.

“It’ll be all right, Isaac,” he ses. “I wouldn’t ‘ave a drink if you asked me to. Don’t seem to care for it now. I was saying so to you on’y last night, wasn’t I, Peter?”

“You was,” ses Peter; “so was I.”

“Then I’ve done you good, Ginger,” ses Isaac, clapping ‘im on the back.

“You ‘ave,” ses Ginger, speaking between his teeth, “and I thank you for it. I don’t want drink; but I thought o’ going to a music-’all this evening.”

“Going to wot?” ses old Isaac, drawing ‘imself up and looking very shocked.

“A music-’all,” ses Ginger, trying to keep ‘is temper.

“A music-’all,” ses Isaac; “why, it’s worse than a pub, Ginger. I should be a very poor friend o’ yours if I let you go there—I couldn’t think of it.”

“Wot’s it got to do with you, you gray-whiskered serpent?” screams Ginger, arf mad with rage. “Why don’t you leave us alone? Why don’t you mind your own business? It’s our money.”

Isaac tried to talk to ‘im, but ‘e wouldn’t listen, and he made such a fuss that at last the coffee-shop keeper told ‘im to go outside. Peter follered ‘im out, and being very upset they went and spent their day’s allowance in the first hour, and then they walked about the streets quarrelling as to the death they’d like old Isaac to ‘ave when ‘is time came.

They went back to their lodgings at dinner-time; but there was no sign of the old man, and, being ‘ungry and thirsty, they took all their spare clothes to a pawnbroker and got enough money to go on with. Just to show their independence they went to two music-’ails, and with a sort of idea that they was doing Isaac a bad turn they spent every farthing afore they got ‘ome, and sat up in bed telling ‘im about the spree they’d ‘ad.

At five o’clock in the morning Peter woke up and saw, to ‘is surprise, that Ginger Dick was dressed and carefully folding up old Isaac’s clothes. At first ‘e thought that Ginger ‘ad gone mad, taking care of the old man’s things like that, but afore ‘e could speak Ginger noticed that ‘e was awake, and stepped over to ‘im and whispered to ‘im to dress without making a noise. Peter did as ‘e was told, and, more puzzled than ever, saw Ginger make up all the old man’s clothes in a bundle and creep out of the room on tiptoe.

“Going to ‘ide ‘is clothes?” ‘e ses.

“Yes,” ses Ginger, leading the way downstairs; “in a pawnshop. We’ll make the old man pay for to-day’s amusements.”

Then Peter see the joke and ‘e begun to laugh so ‘ard that Ginger ‘ad to threaten to knock ‘is head off to quiet ‘im. Ginger laughed ‘imself when they got outside, and at last, arter walking about till the shops opened, they got into a pawnbroker’s and put old Isaac’s clothes up for fifteen shillings.

First thing they did was to ‘ave a good breakfast, and after that they came out smiling all over and began to spend a ‘appy day. Ginger was in tip-top spirits and so was Peter, and the idea that old Isaac was in bed while they was drinking ‘is clothes pleased them more than anything. Twice that evening policemen spoke to Ginger for dancing on the pavement, and by the time the money was spent it took Peter all ‘is time to get ‘im ‘ome.

Old Isaac was in bed when they got there, and the temper ‘e was in was shocking; but Ginger sat on ‘is bed and smiled at ‘im as if ‘e was saying compliments to ‘im.

“Where’s my clothes?” ses the old man, shaking ‘is fist at the two of ‘em.

Ginger smiled at ‘im; then ‘e shut ‘is eyes and dropped off to sleep.

“Where’s my clothes?” ses Isaac, turning to Peter. “Closhe?” ses Peter, staring at ‘im.

“Where are they?” ses Isaac.

It was a long time afore Peter could understand wot ‘e meant, but as soon as ‘e did ‘e started to look for ‘em. Drink takes people in different ways, and the way it always took Peter was to make ‘im one o’ the most obliging men that ever lived. He spent arf the night crawling about on all fours looking for the clothes, and four or five times old Isaac woke up from dreams of earthquakes to find Peter ‘ad got jammed under ‘is bed, and was wondering what ‘ad ‘appened to ‘im.

None of ‘em was in the best o’ tempers when they woke up next morning, and Ginger ‘ad ‘ardly got ‘is eyes open before Isaac was asking ‘im about ‘is clothes agin.

“Don’t bother me about your clothes,” ses Ginger; “talk about something else for a change.”

“Where are they?” ses Isaac, sitting on the edge of ‘is bed.

Ginger yawned and felt in ‘is waistcoat pocket—for neither of ‘em ‘ad undressed—and then ‘e took the pawn-ticket out and threw it on the floor. Isaac picked it up, and then ‘e began to dance about the room as if ‘e’d gone mad.

“Do you mean to tell me you’ve pawned my clothes?” he shouts.

“Me and Peter did,” ses Ginger, sitting up in bed and getting ready for a row.

Isaac dropped on the bed agin all of a ‘cap. “And wot am I to do?” he ses.

“If you be’ave yourself,” ses Ginger, “and give us our money, me and Peter’ll go and get ‘em out agin. When we’ve ‘ad breakfast, that is. There’s no hurry.”

“But I ‘aven’t got the money,” ses Isaac; “it was all sewn up in the lining of the coat. I’ve on’y got about five shillings. You’ve made a nice mess of it, Ginger, you ‘ave.”

“You’re a silly fool, Ginger, that’s wot you are,” ses Peter.

“Sewn up in the lining of the coat?” ses Ginger, staring.

“The bank-notes was,” ses Isaac, “and three pounds in gold ‘idden in the cap. Did you pawn that too?”

Ginger got up in ‘is excitement and walked up and down the room. “We must go and get ‘em out at once,” he ses.

“And where’s the money to do it with?” ses Peter.

Ginger ‘adn’t thought of that, and it struck ‘im all of a heap. None of ‘em seemed to be able to think of a way of getting the other ten shillings wot was wanted, and Ginger was so upset that ‘e took no notice of the things Peter kept saying to ‘im.

“Let’s go and ask to see ‘em, and say we left a railway-ticket in the pocket,” ses Peter.

Isaac shook ‘is ‘ead. “There’s on’y one way to do it,” he ses. “We shall ‘ave to pawn your clothes, Ginger, to get mine out with.”

“That’s the on’y way, Ginger,” ses Peter, brightening up. “Now, wot’s the good o’ carrying on like that? It’s no worse for you to be without your clothes for a little while than it was for pore old Isaac.”

It took ‘em quite arf an hour afore they could get Ginger to see it. First of all ‘e wanted Peter’s clothes to be took instead of ‘is, and when Peter pointed out that they was too shabby to fetch ten shillings ‘e ‘ad a lot o’ nasty things to say about wearing such old rags, and at last, in a terrible temper, ‘e took ‘is clothes off and pitched ‘em in a ‘eap on the floor.

“If you ain’t back in arf an hour, Peter,” ‘e ses, scowling at ‘im, “you’ll ‘ear from me, I can tell you.”

“Don’t you worry about that,” ses Isaac, with a smile. “I’m going to take ‘em.”

“You?” ses Ginger; “but you can’t. You ain’t got no clothes.”

“I’m going to wear Peter’s,” ses Isaac, with a smile.

Peter asked ‘im to listen to reason, but it was all no good. He’d got the pawn-ticket, and at last Peter, forgetting all he’d said to Ginger Dick about using bad langwidge, took ‘is clothes off, one by one, and dashed ‘em on the floor, and told Isaac some of the things ‘e thought of ‘im.

The old man didn’t take any notice of ‘im. He dressed ‘imself up very slow and careful in Peter’s clothes, and then ‘e drove ‘em nearly crazy by wasting time making ‘is bed.

“Be as quick as you can, Isaac,” ses Ginger, at last; “think of us two a-sitting ‘ere waiting for you.”

“I sha’n’t forget it,” ses Isaac, and ‘e came back to the door after ‘e’d gone arf-way down the stairs to ask ‘em not to go out on the drink while ‘e was away.

It was nine o’clock when he went, and at ha’-past nine Ginger began to get impatient and wondered wot ‘ad ‘appened to ‘im, and when ten o’clock came and no Isaac they was both leaning out of the winder with blankets over their shoulders looking up the road. By eleven o’clock Peter was in very low spirits and Ginger was so mad ‘e was afraid to speak to ‘im.

They spent the rest o’ that day ‘anging out of the winder, but it was not till ha’-past four in the after-noon that Isaac, still wearing Peter’s clothes and carrying a couple of large green plants under ‘is arm, turned into the road, and from the way ‘e was smiling they thought it must be all right.

“Wot ‘ave you been such a long time for?” ses Ginger, in a low, fierce voice, as Isaac stopped underneath the winder and nodded up to ‘em.

“I met a old friend,” ses Isaac.

“Met a old friend?” ses Ginger, in a passion. “Wot d’ye mean, wasting time like that while we was sitting up ‘ere waiting and starving?”

“I ‘adn’t seen ‘im for years,” ses Isaac, “and time slipped away afore I noticed it.”

“I dessay,” ses Ginger, in a bitter voice. “Well, is the money all right?”

“I don’t know,” ses Isaac; “I ain’t got the clothes.”

“Wot?” ses Ginger, nearly falling out of the winder. “Well, wot ‘ave you done with mine, then? Where are they? Come upstairs.”

“I won’t come upstairs, Ginger,” ses Isaac, “because I’m not quite sure whether I’ve done right. But I’m not used to going into pawnshops, and I walked about trying to make up my mind to go in and couldn’t.”

“Well, wot did you do then?” ses Ginger, ‘ardly able to contain hisself.

“While I was trying to make up my mind,” ses old Isaac, “I see a man with a barrer of lovely plants. ‘E wasn’t asking money for ‘em, only old clothes.”

“Old clothes?” ses Ginger, in a voice as if ‘e was being suffocated.

“I thought they’d be a bit o’ green for you to look at,” ses the old man, ‘olding the plants up; “there’s no knowing ‘ow long you’ll be up there. The big one is yours, Ginger, and the other is for Peter.”

“‘Ave you gone mad, Isaac?” ses Peter, in a trembling voice, arter Ginger ‘ad tried to speak and couldn’t.

Isaac shook ‘is ‘ead and smiled up at ‘em, and then, arter telling Peter to put Ginger’s blanket a little more round ‘is shoulders, for fear ‘e should catch cold, ‘e said ‘e’d ask the landlady to send ‘em up some bread and butter and a cup o’ tea.

They ‘eard ‘im talking to the landlady at the door, and then ‘e went off in a hurry without looking behind ‘im, and the landlady walked up and down on the other side of the road with ‘er apron stuffed in ‘er mouth, pretending to be looking at ‘er chimney-pots.

Isaac didn’t turn up at all that night, and by next morning those two unfortunate men see ‘ow they’d been done. It was quite plain to them that Isaac ‘ad been deceiving them, and Peter was pretty certain that ‘e took the money out of the bed while ‘e was fussing about making it. Old Isaac kept ‘em there for three days, sending ‘em in their clothes bit by bit and two shillings a day to live on; but they didn’t set eyes on ‘im agin until they all signed on aboard the Planet, and they didn’t set eyes on their money until they was two miles below Gravesend.

THE CASTAWAY

Mrs. John Boxer stood at the door of the shop with her hands clasped on her apron. The short day had drawn to a close, and the lamps in the narrow little thorough-fares of Shinglesea were already lit. For a time she stood listening to the regular beat of the sea on the beach some half-mile distant, and then with a slight shiver stepped back into the shop and closed the door.

The little shop with its wide-mouthed bottles of sweets was one of her earliest memories. Until her marriage she had known no other home, and when her husband was lost with the North Star some three years before, she gave up her home in Poplar and returned to assist her mother in the little shop.

In a restless mood she took up a piece of needle-work, and a minute or two later put it down again. A glance through the glass of the door leading into the small parlour revealed Mrs. Gimpson, with a red shawl round her shoulders, asleep in her easy-chair.

Mrs. Boxer turned at the clang of the shop bell, and then, with a wild cry, stood gazing at the figure of a man standing in the door-way. He was short and bearded, with oddly shaped shoulders, and a left leg which was not a match; but the next moment Mrs. Boxer was in his arms sobbing and laughing together.

Mrs. Gimpson, whose nerves were still quivering owing to the suddenness with which she had been awakened, came into the shop; Mr. Boxer freed an arm, and placing it round her waist kissed her with some affection on the chin.

“He’s come back!” cried Mrs. Boxer, hysterically.

“Thank goodness,” said Mrs. Gimpson, after a moment’s deliberation.

“He’s alive!” cried Mrs. Boxer. “He’s alive!”

She half-dragged and half-led him into the small parlour, and thrusting him into the easy-chair lately vacated by Mrs. Gimpson seated herself upon his knee, regardless in her excitement that the rightful owner was with elaborate care selecting the most uncomfortable chair in the room.

“Fancy his coming back!” said Mrs. Boxer, wiping her eyes. “How did you escape, John? Where have you been? Tell us all about it.”

Mr. Boxer sighed. “It ‘ud be a long story if I had the gift of telling of it,” he said, slowly, “but I’ll cut it short for the present. When the North Star went down in the South Pacific most o’ the hands got away in the boats, but I was too late. I got this crack on the head with something falling on it from aloft. Look here.”

He bent his head, and Mrs. Boxer, separating the stubble with her fingers, uttered an exclamation of pity and alarm at the extent of the scar; Mrs. Gimpson, craning forward, uttered a sound which might mean anything—even pity.

“When I come to my senses,” continued Mr. Boxer, “the ship was sinking, and I just got to my feet when she went down and took me with her. How I escaped I don’t know. I seemed to be choking and fighting for my breath for years, and then I found myself floating on the sea and clinging to a grating. I clung to it all night, and next day I was picked up by a native who was paddling about in a canoe, and taken ashore to an island, where I lived for over two years. It was right out o’ the way o’ craft, but at last I was picked up by a trading schooner named the Pearl, belonging to Sydney, and taken there. At Sydney I shipped aboard the Marston Towers, a steamer, and landed at the Albert Docks this morning.”

“Poor John,” said his wife, holding on to his arm. “How you must have suffered!”

“I did,” said Mr. Boxer. “Mother got a cold?” he inquired, eying that lady.

“No, I ain’t,” said Mrs. Gimpson, answering for herself. “Why didn’t you write when you got to Sydney?”

“Didn’t know where to write to,” replied Mr. Boxer, staring. “I didn’t know where Mary had gone to.”

“You might ha’ wrote here,” said Mrs. Gimpson.

“Didn’t think of it at the time,” said Mr. Boxer. “One thing is, I was very busy at Sydney, looking for a ship. However, I’m ‘ere now.”

“I always felt you’d turn up some day,” said Mrs. Gimpson. “I felt certain of it in my own mind. Mary made sure you was dead, but I said ‘no, I knew better.’”

There was something in Mrs. Gimpson’s manner of saying this that impressed her listeners unfavourably. The impression was deepened when, after a short, dry laugh a propos of nothing, she sniffed again—three times.

“Well, you turned out to be right,” said Mr. Boxer, shortly.

“I gin’rally am,” was the reply; “there’s very few people can take me in.”

She sniffed again.

“Were the natives kind to you?” inquired Mrs. Boxer, hastily, as she turned to her husband.

“Very kind,” said the latter. “Ah! you ought to have seen that island. Beautiful yellow sands and palm-trees; cocoa-nuts to be ‘ad for the picking, and nothing to do all day but lay about in the sun and swim in the sea.”

“Any public-’ouses there?” inquired Mrs. Gimpson.

“Cert’nly not,” said her son-in-law. “This was an island—one o’ the little islands in the South Pacific Ocean.”

“What did you say the name o’ the schooner was?” inquired Mrs. Gimpson.

“Pearl,” replied Mr. Boxer, with the air of a resentful witness under cross-examination.

“And what was the name o’ the captin?” said Mrs. Gimpson.

“Thomas—Henery—Walter—Smith,” said Mr. Boxer, with somewhat unpleasant emphasis.

“An’ the mate’s name?”

“John Brown,” was the reply.

“Common names,” commented Mrs. Gimpson, “very common. But I knew you’d come back all right—I never ‘ad no alarm. ‘He’s safe and happy, my dear,’ I says. ‘He’ll come back all in his own good time.’”

“What d’you mean by that?” demanded the sensitive Mr. Boxer. “I come back as soon as I could.”

“You know you were anxious, mother,” interposed her daughter. “Why, you insisted upon our going to see old Mr. Silver about it.”

“Ah! but I wasn’t uneasy or anxious afterwards,” said Mrs. Gimpson, compressing her lips.

“Who’s old Mr. Silver, and what should he know about it?” inquired Mr. Boxer.

“He’s a fortune-teller,” replied his wife. “Reads the stars,” said his mother-in-law.

Mr. Boxer laughed—a good ringing laugh. “What did he tell you?” he inquired. “Nothing,” said his wife, hastily. “Ah!” said Mr. Boxer, waggishly, “that was wise of ‘im. Most of us could tell fortunes that way.”

“That’s wrong,” said Mrs. Gimpson to her daughter, sharply. “Right’s right any day, and truth’s truth. He said that he knew all about John and what he’d been doing, but he wouldn’t tell us for fear of ‘urting our feelings and making mischief.”

“Here, look ‘ere,” said Mr. Boxer, starting up; “I’ve ‘ad about enough o’ this. Why don’t you speak out what you mean? I’ll mischief ‘im, the old humbug. Old rascal.”

“Never mind, John,” said his wife, laying her hand upon his arm. “Here you are safe and sound, and as for old Mr. Silver, there’s a lot o’ people don’t believe in him.”

“Ah! they don’t want to,” said Mrs. Gimpson, obstinately. “But don’t forget that he foretold my cough last winter.”

“Well, look ‘ere,” said Mr. Boxer, twisting his short, blunt nose into as near an imitation of a sneer as he could manage, “I’ve told you my story and I’ve got witnesses to prove it. You can write to the master of the Marston Towers if you like, and other people besides. Very well, then; let’s go and see your precious old fortune-teller. You needn’t say who I am; say I’m a friend, and tell ‘im never to mind about making mischief, but to say right out where I am and what I’ve been doing all this time. I have my ‘opes it’ll cure you of your superstitiousness.”

“We’ll go round after we’ve shut up, mother,” said Mrs. Boxer. “We’ll have a bit o’ supper first and then start early.”

Mrs. Gimpson hesitated. It is never pleasant to submit one’s superstitions to the tests of the unbelieving, but after the attitude she had taken up she was extremely loath to allow her son-in-law a triumph.

“Never mind, we’ll say no more about it,” she said, primly, “but I ‘ave my own ideas.”

“I dessay,” said Mr. Boxer; “but you’re afraid for us to go to your old fortune-teller. It would be too much of a show-up for ‘im.”

“It’s no good your trying to aggravate me, John Boxer, because you can’t do it,” said Mrs. Gimpson, in a voice trembling with passion.

“O’ course, if people like being deceived they must be,” said Mr. Boxer; “we’ve all got to live, and if we’d all got our common sense fortune-tellers couldn’t. Does he tell fortunes by tea-leaves or by the colour of your eyes?”

“Laugh away, John Boxer,” said Mrs. Gimpson, icily; “but I shouldn’t have been alive now if it hadn’t ha’ been for Mr. Silver’s warnings.”

“Mother stayed in bed for the first ten days in July,” explained Mrs. Boxer, “to avoid being bit by a mad dog.”

“Tchee—tchee—tchee,” said the hapless Mr. Boxer, putting his hand over his mouth and making noble efforts to restrain himself; “tchee—tch

“I s’pose you’d ha’ laughed more if I ‘ad been bit?” said the glaring Mrs. Gimpson.

“Well, who did the dog bite after all?” inquired Mr. Boxer, recovering.

“You don’t understand,” replied Mrs. Gimpson, pityingly; “me being safe up in bed and the door locked, there was no mad dog. There was no use for it.”

“Well,” said Mr. Boxer, “me and Mary’s going round to see that old deceiver after supper, whether you come or not. Mary shall tell ‘im I’m a friend, and ask him to tell her everything about ‘er husband. Nobody knows me here, and Mary and me’ll be affectionate like, and give ‘im to understand we want to marry. Then he won’t mind making mischief.”

“You’d better leave well alone,” said Mrs. Gimpson.

Mr. Boxer shook his head. “I was always one for a bit o’ fun,” he said, slowly. “I want to see his face when he finds out who I am.”

Mrs. Gimpson made no reply; she was looking round for the market-basket, and having found it she left the reunited couple to keep house while she went out to obtain a supper which should, in her daughter’s eyes, be worthy of the occasion.

She went to the High Street first and made her purchases, and was on the way back again when, in response to a sudden impulse, as she passed the end of Crowner’s Alley, she turned into that small by-way and knocked at the astrologer’s door.

A slow, dragging footstep was heard approaching in reply to the summons, and the astrologer, recognising his visitor as one of his most faithful and credulous clients, invited her to step inside. Mrs. Gimpson complied, and, taking a chair, gazed at the venerable white beard and small, red-rimmed eyes of her host in some perplexity as to how to begin.

“My daughter’s coming round to see you presently,” she said, at last.

The astrologer nodded.

“She—she wants to ask you about ‘er husband,” faltered’ Mrs. Gimpson; “she’s going to bring a friend with her—a man who doesn’t believe in your knowledge. He—he knows all about my daughter’s husband, and he wants to see what you say you know about him.”

The old man put on a pair of huge horn spectacles and eyed her carefully.

“You’ve got something on your mind,” he said, at last; “you’d better tell me everything.”

Mrs. Gimpson shook her head.

“There’s some danger hanging over you,” continued Mr. Silver, in a low, thrilling voice; “some danger in connection with your son-in-law. There,” he waved a lean, shrivelled hand backward and for-ward as though dispelling a fog, and peered into distance—“there is something forming over you. You—or somebody—are hiding something from me.”

Mrs. Gimpson, aghast at such omniscience, sank backward in her chair.

“Speak,” said the old man, gently; “there is no reason why you should be sacrificed for others.”

Mrs. Gimpson was of the same opinion, and in some haste she reeled off the events of the evening. She had a good memory, and no detail was lost.

“Strange, strange,” said the venerable Mr. Silver, when he had finished. “He is an ingenious man.”

“Isn’t it true?” inquired his listener. “He says he can prove it. And he is going to find out what you meant by saying you were afraid of making mischief.”

“He can prove some of it,” said the old man, his eyes snapping spitefully. “I can guarantee that.”

“But it wouldn’t have made mischief if you had told us that,” ventured Mrs. Gimpson. “A man can’t help being cast away.”

“True,” said the astrologer, slowly; “true. But let them come and question me; and whatever you do, for your own sake don’t let a soul know that you have been here. If you do, the danger to yourself will be so terrible that even I may be unable to help you.”

Mrs. Gimpson shivered, and more than ever impressed by his marvellous powers made her way slowly home, where she found the unconscious Mr. Boxer relating his adventures again with much gusto to a married couple from next door.

“It’s a wonder he’s alive,” said Mr. Jem Thompson, looking up as the old woman entered the room; “it sounds like a story-book. Show us that cut on your head again, mate.”

The obliging Mr. Boxer complied.

“We’re going on with ‘em after they’ve ‘ad sup-per,” continued Mr. Thompson, as he and his wife rose to depart. “It’ll be a fair treat to me to see old Silver bowled out.”

Mrs. Gimpson sniffed and eyed his retreating figure disparagingly; Mrs. Boxer, prompted by her husband, began to set the table for supper.

It was a lengthy meal, owing principally to Mr. Boxer, but it was over at last, and after that gentleman had assisted in shutting up the shop they joined the Thompsons, who were waiting outside, and set off for Crowner’s Alley. The way was enlivened by Mr. Boxer, who had thrills of horror every ten yards at the idea of the supernatural things he was about to witness, and by Mr. Thompson, who, not to be outdone, persisted in standing stock-still at frequent intervals until he had received the assurances of his giggling better-half that he would not be made to vanish in a cloud of smoke.

By the time they reached Mr. Silver’s abode the party had regained its decorum, and, except for a tremendous shudder on the part of Mr. Boxer as his gaze fell on a couple of skulls which decorated the magician’s table, their behaviour left nothing to be desired. Mrs. Gimpson, in a few awkward words, announced the occasion of their visit. Mr. Boxer she introduced as a friend of the family from London.

“I will do what I can,” said the old man, slowly, as his visitors seated themselves, “but I can only tell you what I see. If I do not see all, or see clearly, it cannot be helped.”

Mr. Boxer winked at Mr. Thompson, and received an understanding pinch in return; Mrs. Thompson in a hot whisper told them to behave themselves.

The mystic preparations were soon complete. A little cloud of smoke, through which the fierce red eyes of the astrologer peered keenly at Mr. Boxer, rose from the table. Then he poured various liquids into a small china bowl and, holding up his hand to command silence, gazed steadfastly into it. “I see pictures,” he announced, in a deep voice. “The docks of a great city; London. I see an ill-shaped man with a bent left leg standing on the deck of a ship.”

Mr. Thompson, his eyes wide open with surprise, jerked Mr. Boxer in the ribs, but Mr. Boxer, whose figure was a sore point with him, made no response.

“The ship leaves the docks,” continued Mr. Silver, still peering into the bowl. “As she passes through the entrance her stern comes into view with the name painted on it. The—the—the——”

“Look agin, old chap,” growled Mr. Boxer, in an undertone.

“The North Star,” said the astrologer. “The ill-shaped man is still standing on the fore-part of the ship; I do not know his name or who he is. He takes the portrait of a beautiful young woman from his pocket and gazes at it earnestly.”

Mrs. Boxer, who had no illusions on the subject of her personal appearance, sat up as though she had been stung; Mr. Thompson, who was about to nudge Mr. Boxer in the ribs again, thought better of it and assumed an air of uncompromising virtue.

“The picture disappears,” said Mr. Silver. “Ah! I see; I see. A ship in a gale at sea. It is the North Star; it is sinking. The ill-shaped man sheds tears and loses his head. I cannot discover the name of this man.”

Mr. Boxer, who had been several times on the point of interrupting, cleared his throat and endeavoured to look unconcerned.

“The ship sinks,” continued the astrologer, in thrilling tones. “Ah! what is this? a piece of wreck-age with a monkey clinging to it? No, no-o. The ill-shaped man again. Dear me!”

His listeners sat spellbound. Only the laboured and intense breathing of Mr. Boxer broke the silence.

“He is alone on the boundless sea,” pursued the seer; “night falls. Day breaks, and a canoe propelled by a slender and pretty but dusky maiden approaches the castaway. She assists him into the canoe and his head sinks on her lap, as with vigorous strokes of her paddle she propels the canoe toward a small island fringed with palm trees.”

“Here, look ‘ere—” began the overwrought Mr. Boxer.

“H’sh, h’sh!” ejaculated the keenly interested Mr. Thompson. “W’y don’t you keep quiet?”

“The picture fades,” continued the old man. “I see another: a native wedding. It is the dusky maiden and the man she rescued. Ah! the wedding is interrupted; a young man, a native, breaks into the group. He has a long knife in his hand. He springs upon the ill-shaped man and wounds him in the head.”

Involuntarily Mr. Boxer’s hand went up to his honourable scar, and the heads of the others swung round to gaze at it. Mrs. Boxer’s face was terrible in its expression, but Mrs. Gimpson’s bore the look of sad and patient triumph of one who knew men and could not be surprised at anything they do.

“The scene vanishes,” resumed the monotonous voice, “and another one forms. The same man stands on the deck of a small ship. The name on the stern is the Peer—no, Paris—no, no, no, Pearl. It fades from the shore where the dusky maiden stands with hands stretched out imploringly. The ill-shaped man smiles and takes the portrait of the young and beautiful girl from his pocket.”

“Look ‘ere,” said the infuriated Mr. Boxer, “I think we’ve ‘ad about enough of this rubbish. I have—more than enough.”

“I don’t wonder at it,” said his wife, trembling furiously. “You can go if you like. I’m going to stay and hear all that there is to hear.”

“You sit quiet,” urged the intensely interested Mr. Thompson. “He ain’t said it’s you. There’s more than one misshaped man in the world, I s’pose?”

“I see an ocean liner,” said the seer, who had appeared to be in a trance state during this colloquy. “She is sailing for England from Australia. I see the name distinctly: the Marston Towers. The same man is on board of her. The ship arrives at London. The scene closes; another one forms. The ill-shaped man is sitting with a woman with a beautiful face —not the same as the photograph.”

“What they can see in him I can’t think,” muttered Mr. Thompson, in an envious whisper. “He’s a perfick terror, and to look at him——”

“They sit hand in hand,” continued the astrologer, raising his voice. “She smiles up at him and gently strokes his head; he——”

A loud smack rang through the room and startled the entire company; Mrs. Boxer, unable to contain herself any longer, had, so far from profiting by the example, gone to the other extreme and slapped her husband’s head with hearty good-will. Mr. Boxer sprang raging to his feet, and in the confusion which ensued the fortune-teller, to the great regret of Mr. Thompson, upset the contents of the magic bowl.

“I can see no more,” he said, sinking hastily into his chair behind the table as Mr. Boxer advanced upon him.

Mrs. Gimpson pushed her son-in-law aside, and laying a modest fee upon the table took her daughter’s arm and led her out. The Thompsons followed, and Mr. Boxer, after an irresolute glance in the direction of the ingenuous Mr. Silver, made his way after them and fell into the rear. The people in front walked on for some time in silence, and then the voice of the greatly impressed Mrs. Thompson was heard, to the effect that if there were only more fortune-tellers in the world there would be a lot more better men.

Mr. Boxer trotted up to his wife’s side. “Look here, Mary,” he began.

“Don’t you speak to me,” said his wife, drawing closer to her mother, “because I won’t answer you.”

Mr. Boxer laughed, bitterly. “This is a nice home-coming,” he remarked.

He fell to the rear again and walked along raging, his temper by no means being improved by observing that Mrs. Thompson, doubtless with a firm belief in the saying that “Evil communications corrupt good manners,” kept a tight hold of her husband’s arm. His position as an outcast was clearly defined, and he ground his teeth with rage as he observed the virtuous uprightness of Mrs. Gimpson’s back. By the time they reached home he was in a spirit of mad recklessness far in advance of the character given him by the astrologer.

His wife gazed at him with a look of such strong interrogation as he was about to follow her into the house that he paused with his foot on the step and eyed her dumbly.

“Have you left anything inside that you want?” she inquired.

Mr. Boxer shook his head. “I only wanted to come in and make a clean breast of it,” he said, in a curious voice; “then I’ll go.”

Mrs. Gimpson stood aside to let him pass, and Mr. Thompson, not to be denied, followed close behind with his faintly protesting wife. They sat down in a row against the wall, and Mr. Boxer, sitting opposite in a hang-dog fashion, eyed them with scornful wrath.

“Well?” said Mrs. Boxer, at last.

“All that he said was quite true,” said her husband, defiantly. “The only thing is, he didn’t tell the arf of it. Altogether, I married three dusky maidens.”

Everybody but Mr. Thompson shuddered with horror.

“Then I married a white girl in Australia,” pursued Mr. Boxer, musingly. “I wonder old Silver didn’t see that in the bowl; not arf a fortune-teller, I call ‘im.”

“What they see in ‘im!” whispered the astounded Mr. Thompson to his wife.

“And did you marry the beautiful girl in the photograph?” demanded Mrs. Boxer, in trembling accents.

“I did,” said her husband.

“Hussy,” cried Mrs. Boxer.

“I married her,” said Mr. Boxer, considering—“I married her at Camberwell, in eighteen ninety-three.”

“Eighteen ninety-three!” said his wife, in a startled voice. “But you couldn’t. Why, you didn’t marry me till eighteen ninety-four.”

“What’s that got to do with it?” inquired the monster, calmly.

Mrs. Boxer, pale as ashes, rose from her seat and stood gazing at him with horror-struck eyes, trying in vain to speak.

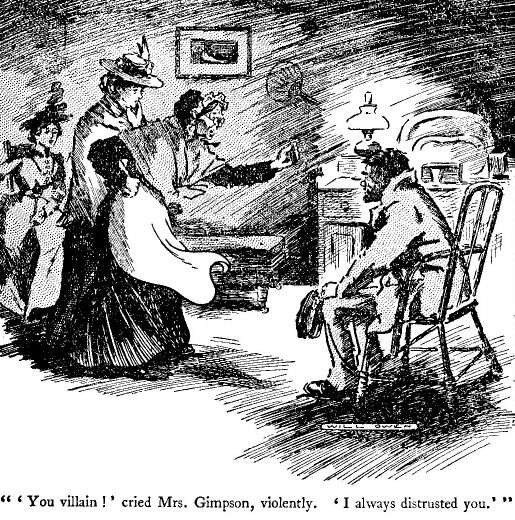

“You villain!” cried Mrs. Gimpson, violently. “I always distrusted you.”

“I know you did,” said Mr. Boxer, calmly. “You’ve been committing bigamy,” cried Mrs. Gimpson.

“Over and over agin,” assented Mr. Boxer, cheerfully. “It’s got to be a ‘obby with me.”

“Was the first wife alive when you married my daughter?” demanded Mrs. Gimpson.

“Alive?” said Mr. Boxer. “O’ course she was. She’s alive now—bless her.”

He leaned back in his chair and regarded with intense satisfaction the horrified faces of the group in front.

“You—you’ll go to jail for this,” cried Mrs. Gimpson, breathlessly. “What is your first wife’s address?”

“I decline to answer that question,” said her son-in-law.

“What is your first wife’s address?” repeated Mrs. Gimpson.

“Ask the fortune-teller,” said Mr. Boxer, with an aggravating smile. “And then get ‘im up in the box as a witness, little bowl and all. He can tell you more than I can.”

“I demand to know her name and address,” cried Mrs. Gimpson, putting a bony arm around the waist of the trembling Mrs. Boxer.

“I decline to give it,” said Mr. Boxer, with great relish. “It ain’t likely I’m going to give myself away like that; besides, it’s agin the law for a man to criminate himself. You go on and start your bigamy case, and call old red-eyes as a witness.”

Mrs. Gimpson gazed at him in speechless wrath and then stooping down conversed in excited whispers with Mrs. Thompson. Mrs. Boxer crossed over to her husband.

“Oh, John,” she wailed, “say it isn’t true, say it isn’t true.”

Mr. Boxer hesitated. “What’s the good o’ me saying anything?” he said, doggedly.

“It isn’t true,” persisted his wife. “Say it isn’t true.”

“What I told you when I first came in this evening was quite true,” said her husband, slowly. “And what I’ve just told you is as true as what that lying old fortune-teller told you. You can please yourself what you believe.”

“I believe you, John,” said his wife, humbly.

Mr. Boxer’s countenance cleared and he drew her on to his knee.

“That’s right,” he said, cheerfully. “So long as you believe in me I don’t care what other people think. And before I’m much older I’ll find out how that old rascal got to know the names of the ships I was aboard. Seems to me somebody’s been talking.”

BLUNDELL’S IMPROVEMENT

Venia Turnbull in a quiet, unobtrusive fashion was enjoying herself. The cool living-room at Turnbull’s farm was a delightful contrast to the hot sunshine without, and the drowsy humming of bees floating in at the open window was charged with hints of slumber to the middle-aged. From her seat by the window she watched with amused interest the efforts of her father—kept from his Sunday afternoon nap by the assiduous attentions of her two admirers—to maintain his politeness.

“Father was so pleased to see you both come in,” she said, softly; “it’s very dull for him here of an afternoon with only me.”

“I can’t imagine anybody being dull with only you,” said Sergeant Dick Daly, turning a bold brown eye upon her.

Mr. John Blundell scowled; this was the third time the sergeant had said the thing that he would have liked to say if he had thought of it.

“I don’t mind being dull,” remarked Mr. Turnbull, casually.

Neither gentleman made any comment.

“I like it,” pursued Mr. Turnbull, longingly; “always did, from a child.”

The two young men looked at each other; then they looked at Venia; the sergeant assumed an expression of careless ease, while John Blundell sat his chair like a human limpet. Mr. Turnbull almost groaned as he remembered his tenacity.

“The garden’s looking very nice,” he said, with a pathetic glance round.

“Beautiful,” assented the sergeant. “I saw it yesterday.”

“Some o’ the roses on that big bush have opened a bit more since then,” said the farmer.

Sergeant Daly expressed his gratification, and said that he was not surprised. It was only ten days since he had arrived in the village on a visit to a relative, but in that short space of time he had, to the great discomfort of Mr. Blundell, made himself wonderfully at home at Mr. Turnbull’s. To Venia he related strange adventures by sea and land, and on subjects of which he was sure the farmer knew nothing he was a perfect mine of information. He began to talk in low tones to Venia, and the heart of Mr. Blundell sank within him as he noted her interest. Their voices fell to a gentle murmur, and the sergeant’s sleek, well-brushed head bent closer to that of his listener. Relieved from his attentions, Mr. Turnbull fell asleep without more ado.

Blundell sat neglected, the unwilling witness of a flirtation he was powerless to prevent. Considering her limited opportunities, Miss Turnbull displayed a proficiency which astonished him. Even the sergeant was amazed, and suspected her of long practice.

“I wonder whether it is very hot outside?” she said, at last, rising and looking out of the window.

“Only pleasantly warm,” said the sergeant. “It would be nice down by the water.”

“I’m afraid of disturbing father by our talk,” said the considerate daughter. “You might tell him we’ve gone for a little stroll when he wakes,” she added, turning to Blundell.

Mr. Blundell, who had risen with the idea of acting the humble but, in his opinion, highly necessary part of chaperon, sat down again and watched blankly from the window until they were out of sight. He was half inclined to think that the exigencies of the case warranted him in arousing the farmer at once.

It was an hour later when the farmer awoke, to find himself alone with Mr. Blundell, a state of affairs for which he strove with some pertinacity to make that aggrieved gentleman responsible.

“Why didn’t you go with them?” he demanded. “Because I wasn’t asked,” replied the other.

Mr. Turnbull sat up in his chair and eyed him disdainfully. “For a great, big chap like you are, John Blundell,” he exclaimed, “it’s surprising what a little pluck you’ve got.”

“I don’t want to go where I’m not wanted,” retorted Mr. Blundell.

“That’s where you make a mistake,” said the other, regarding him severely; “girls like a masterful man, and, instead of getting your own way, you sit down quietly and do as you’re told, like a tame—tame—”

“Tame what?” inquired Mr. Blundell, resentfully.

“I don’t know,” said the other, frankly; “the tamest thing you can think of. There’s Daly laughing in his sleeve at you, and talking to Venia about Waterloo and the Crimea as though he’d been there. I thought it was pretty near settled between you.”

“So did I,” said Mr. Blundell.

“You’re a big man, John,” said the other, “but you’re slow. You’re all muscle and no head.”

“I think of things afterward,” said Blundell, humbly; “generally after I get to bed.”

Mr. Turnbull sniffed, and took a turn up and down the room; then he closed the door and came toward his friend again.

“I dare say you’re surprised at me being so anxious to get rid of Venia,” he said, slowly, “but the fact is I’m thinking of marrying again myself.”

“You!” said the startled Mr. Blundell.

“Yes, me,” said the other, somewhat sharply. “But she won’t marry so long as Venia is at home. It’s a secret, because if Venia got to hear of it she’d keep single to prevent it. She’s just that sort of girl.”

Mr. Blundell coughed, but did not deny it. “Who is it?” he inquired.

“Miss Sippet,” was the reply. “She couldn’t hold her own for half an hour against Venia.”

Mr. Blundell, a great stickler for accuracy, reduced the time to five minutes.

“And now,” said the aggrieved Mr. Turnbull, “now, so far as I can see, she’s struck with Daly. If she has him it’ll be years and years before they can marry. She seems crazy about heroes. She was talking to me the other night about them. Not to put too fine a point on it, she was talking about you.”

Mr. Blundell blushed with pleased surprise.

“Said you were not a hero,” explained Mr. Turnbull. “Of course, I stuck up for you. I said you’d got too much sense to go putting your life into danger. I said you were a very careful man, and I told her how particular you was about damp sheets. Your housekeeper told me.”

“It’s all nonsense,” said Blundell, with a fiery face. “I’ll send that old fool packing if she can’t keep her tongue quiet.”

“It’s very sensible of you, John,” said Mr. Turnbull, “and a sensible girl would appreciate it. Instead of that, she only sniffed when I told her how careful you always were to wear flannel next to your skin. She said she liked dare-devils.”

“I suppose she thinks Daly is a dare-devil,” said the offended Mr. Blundell. “And I wish people wouldn’t talk about me and my skin. Why can’t they mind their own business?”

Mr. Turnbull eyed him indignantly, and then, sitting in a very upright position, slowly filled his pipe, and declining a proffered match rose and took one from the mantel-piece.

“I was doing the best I could for you,” he said, staring hard at the ingrate. “I was trying to make Venia see what a careful husband you would make. Miss Sippet herself is most particular about such things— and Venia seemed to think something of it, because she asked me whether you used a warming-pan.”

Mr. Blundell got up from his chair and, without going through the formality of bidding his host good-by, quitted the room and closed the door violently behind him. He was red with rage, and he brooded darkly as he made his way home on the folly of carrying on the traditions of a devoted mother without thinking for himself.

For the next two or three days, to Venia’s secret concern, he failed to put in an appearance at the farm—a fact which made flirtation with the sergeant a somewhat uninteresting business. Her sole recompense was the dismay of her father, and for his benefit she dwelt upon the advantages of the Army in a manner that would have made the fortune of a recruiting-sergeant.

“She’s just crazy after the soldiers,” he said to Mr. Blundell, whom he was trying to spur on to a desperate effort. “I’ve been watching her close, and I can see what it is now; she’s romantic. You’re too slow and ordinary for her. She wants somebody more dazzling. She told Daly only yesterday afternoon that she loved heroes. Told it to him to his face. I sat there and heard her. It’s a pity you ain’t a hero, John.”

“Yes,” said Mr. Blundell; “then, if I was, I expect she’d like something else.”

The other shook his head. “If you could only do something daring,” he murmured; “half-kill some-body, or save somebody’s life, and let her see you do it. Couldn’t you dive off the quay and save some-body’s life from drowning?”

“Yes, I could,” said Blundell, “if somebody would only tumble in.”

“You might pretend that you thought you saw somebody drowning,” suggested Mr. Turnbull.

“And be laughed at,” said Mr. Blundell, who knew his Venia by heart.

“You always seem to be able to think of objections,” complained Mr. Turnbull; “I’ve noticed that in you before.”

“I’d go in fast enough if there was anybody there,” said Blundell. “I’m not much of a swimmer, but—”

“All the better,” interrupted the other; “that would make it all the more daring.”

“And I don’t much care if I’m drowned,” pursued the younger man, gloomily.

Mr. Turnbull thrust his hands in his pockets and took a turn or two up and down the room. His brows were knitted and his lips pursed. In the presence of this mental stress Mr. Blundell preserved a respectful silence.

“We’ll all four go for a walk on the quay on Sunday afternoon,” said Mr. Turnbull, at last.

“On the chance?” inquired his staring friend.

“On the chance,” assented the other; “it’s just possible Daly might fall in.”

“He might if we walked up and down five million times,” said Blundell, unpleasantly.

“He might if we walked up and down three or four times,” said Mr. Turnbull, “especially if you happened to stumble.”

“I never stumble,” said the matter-of-fact Mr. Blundell. “I don’t know anybody more sure-footed than I am.”

“Or thick-headed,” added the exasperated Mr. Turnbull.

Mr. Blundell regarded him patiently; he had a strong suspicion that his friend had been drinking.

“Stumbling,” said Mr. Turnbull, conquering his annoyance with an effort “stumbling is a thing that might happen to anybody. You trip your foot against a stone and lurch up against Daly; he tumbles overboard, and you off with your jacket and dive in off the quay after him. He can’t swim a stroke.”

Mr. Blundell caught his breath and gazed at him in speechless amaze.

“There’s sure to be several people on the quay if it’s a fine afternoon,” continued his instructor. “You’ll have half Dunchurch round you, praising you and patting you on the back—all in front of Venia, mind you. It’ll be put in all the papers and you’ll get a medal.”

“And suppose we are both drowned?” said Mr. Blundell, soberly.

“Drowned? Fiddlesticks!” said Mr. Turnbull. “However, please yourself. If you’re afraid——”

“I’ll do it,” said Blundell, decidedly.

“And mind,” said the other, “don’t do it as if it’s as easy as kissing your fingers; be half-drowned yourself, or at least pretend to be. And when you’re on the quay take your time about coming round. Be longer than Daly is; you don’t want him to get all the pity.”

“All right,” said the other.

“After a time you can open your eyes,” went on his instructor; “then, if I were you, I should say, ‘Good-bye, Venia,’ and close ‘em again. Work it up affecting, and send messages to your aunts.”

“It sounds all right,” said Blundell.

“It is all right,” said Mr. Turnbull. “That’s just the bare idea I’ve given you. It’s for you to improve upon it. You’ve got two days to think about it.”

Mr. Blundell thanked him, and for the next two days thought of little else. Being a careful man he made his will, and it was in a comparatively cheerful frame of mind that he made his way on Sunday afternoon to Mr. Turnbull’s.

The sergeant was already there conversing in low tones with Venia by the window, while Mr. Turnbull, sitting opposite in an oaken armchair, regarded him with an expression which would have shocked Iago.

“We were just thinking of having a blow down by the water,” he said, as Blundell entered.

“What! a hot day like this?” said Venia.

“I was just thinking how beautifully cool it is in here,” said the sergeant, who was hoping for a repetition of the previous Sunday’s performance.

“It’s cooler outside,” said Mr. Turnbull, with a wilful ignoring of facts; “much cooler when you get used to it.”

He led the way with Blundell, and Venia and the sergeant, keeping as much as possible in the shade of the dust-powdered hedges, followed. The sun was blazing in the sky, and scarce half-a-dozen people were to be seen on the little curved quay which constituted the usual Sunday afternoon promenade. The water, a dozen feet below, lapped cool and green against the stone sides.

At the extreme end of the quay, underneath the lantern, they all stopped, ostensibly to admire a full-rigged ship sailing slowly by in the distance, but really to effect the change of partners necessary to the after-noon’s business. The change gave Mr. Turnbull some trouble ere it was effected, but he was successful at last, and, walking behind the two young men, waited somewhat nervously for developments.

Twice they paraded the length of the quay and nothing happened. The ship was still visible, and, the sergeant halting to gaze at it, the company lost their formation, and he led the complaisant Venia off from beneath her father’s very nose.

“You’re a pretty manager, you are, John Blundell,” said the incensed Mr. Turnbull.

“I know what I’m about,” said Blundell, slowly.

“Well, why don’t you do it?” demanded the other. “I suppose you are going to wait until there are more people about, and then perhaps some of them will see you push him over.”

“It isn’t that,” said Blundell, slowly, “but you told me to improve on your plan, you know, and I’ve been thinking out improvements.”

“Well?” said the other.

“It doesn’t seem much good saving Daly,” said Blundell; “that’s what I’ve been thinking. He would be in as much danger as I should, and he’d get as much sympathy; perhaps more.”

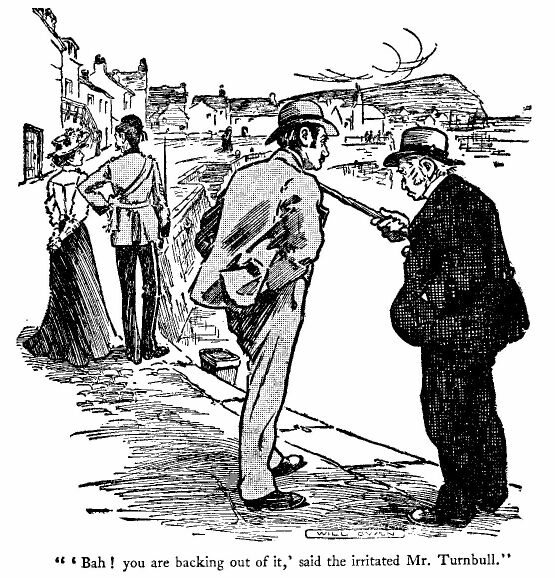

“Do you mean to tell me that you are backing out of it?” demanded Mr. Turnbull.

“No,” said Blundell, slowly, “but it would be much better if I saved somebody else. I don’t want Daly to be pitied.”

“Bah! you are backing out of it,” said the irritated Mr. Turnbull. “You’re afraid of a little cold water.”

“No, I’m not,” said Blundell; “but it would be better in every way to save somebody else. She’ll see Daly standing there doing nothing, while I am struggling for my life. I’ve thought it all out very carefully. I know I’m not quick, but I’m sure, and when I make up my mind to do a thing, I do it. You ought to know that.”

“That’s all very well,” said the other; “but who else is there to push in?”

“That’s all right,” said Blundell, vaguely. “Don’t you worry about that; I shall find somebody.”

Mr. Turnbull turned and cast a speculative eye along the quay. As a rule, he had great confidence in Blundell’s determination, but on this occasion he had his doubts.

“Well, it’s a riddle to me,” he said, slowly. “I give it up. It seems— Halloa! Good heavens, be careful. You nearly had me in then.”

“Did I?” said Blundell, thickly. “I’m very sorry.”

Mr. Turnbull, angry at such carelessness, accepted the apology in a grudging spirit and trudged along in silence. Then he started nervously as a monstrous and unworthy suspicion occurred to him. It was an incredible thing to suppose, but at the same time he felt that there was nothing like being on the safe side, and in tones not quite free from significance he intimated his desire of changing places with his awkward friend.

“It’s all right,” said Blundell, soothingly.

“I know it is,” said Mr. Turnbull, regarding him fixedly; “but I prefer this side. You very near had me over just now.”

“I staggered,” said Mr. Blundell.

“Another inch and I should have been overboard,” said Mr. Turnbull, with a shudder. “That would have been a nice how d’ye do.”

Mr. Blundell coughed and looked seaward. “Accidents will happen,” he murmured.

They reached the end of the quay again and stood talking, and when they turned once more the sergeant was surprised and gratified at the ease with which he bore off Venia. Mr. Turnbull and Blundell followed some little way behind, and the former gentleman’s suspicions were somewhat lulled by finding that his friend made no attempt to take the inside place. He looked about him with interest for a likely victim, but in vain.

“What are you looking at?” he demanded, impatiently, as Blundell suddenly came to a stop and gazed curiously into the harbour.

“Jelly-fish,” said the other, briefly. “I never saw such a monster. It must be a yard across.”

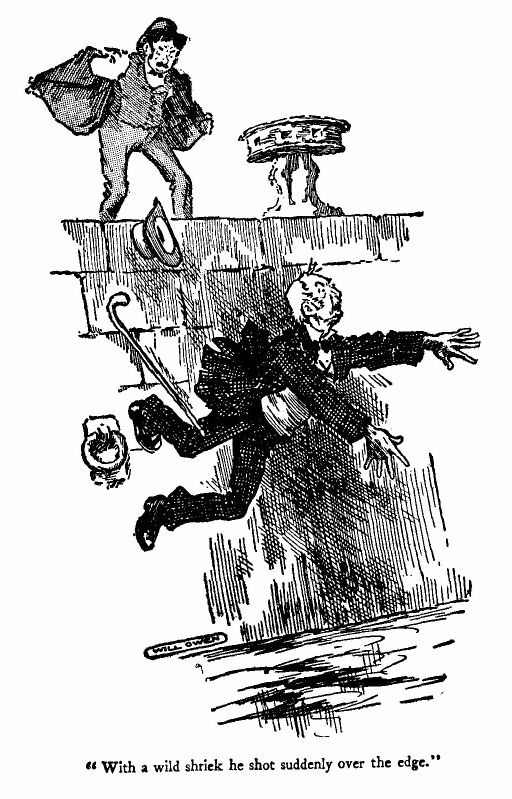

Mr. Turnbull stopped, but could see nothing, and even when Blundell pointed it out with his finger he had no better success. He stepped forward a pace, and his suspicions returned with renewed vigour as a hand was laid caressingly on his shoulder. The next moment, with a wild shriek, he shot suddenly over the edge and disappeared. Venia and the sergeant, turning hastily, were just in time to see the fountain which ensued on his immersion.

“Oh, save him!” cried Venia.

The sergeant ran to the edge and gazed in helpless dismay as Mr. Turnbull came to the surface and disappeared again. At the same moment Blundell, who had thrown off his coat, dived into the harbour and, rising rapidly to the surface, caught the fast-choking Mr. Turnbull by the collar.

“Keep still,” he cried, sharply, as the farmer tried to clutch him; “keep still or I’ll let you go.”

“Help!” choked the farmer, gazing up at the little knot of people which had collected on the quay.

A stout fisherman who had not run for thirty years came along the edge of the quay at a shambling trot, with a coil of rope over his arm. John Blundell saw him and, mindful of the farmer’s warning about kissing of fingers, etc., raised his disengaged arm and took that frenzied gentleman below the surface again. By the time they came up he was very glad for his own sake to catch the line skilfully thrown by the old fisherman and be drawn gently to the side.

“I’ll tow you to the steps,” said the fisherman; “don’t let go o’ the line.”

Mr. Turnbull saw to that; he wound the rope round his wrist and began to regain his presence of mind as they were drawn steadily toward the steps. Willing hands drew them out of the water and helped them up on to the quay, where Mr. Turnbull, sitting in his own puddle, coughed up salt water and glared ferociously at the inanimate form of Mr. Blundell. Sergeant Daly and another man were rendering what they piously believed to be first aid to the apparently drowned, while the stout fisherman, with both hands to his mouth, was yelling in heart-rending accents for a barrel.

“He—he—push—pushed me in,” gasped the choking Mr. Turnbull.

Nobody paid any attention to him; even Venia, seeing that he was safe, was on her knees by the side of the unconscious Blundell.

“He—he’s shamming,” bawled the neglected Mr. Turnbull.

“Shame!” said somebody, without even looking round.

“He pushed me in,” repeated Mr. Turnbull. “He pushed me in.”

“Oh, father,” said Venia, with a scandalised glance at him, “how can you?”

“Shame!” said the bystanders, briefly, as they, watched anxiously for signs of returning life on the part of Mr. Blundell. He lay still with his eyes closed, but his hearing was still acute, and the sounds of a rapidly approaching barrel trundled by a breathless Samaritan did him more good than anything.

“Good-bye, Venia,” he said, in a faint voice; “good-bye.”

Miss Turnbull sobbed and took his hand.

“He’s shamming,” roared Mr. Turnbull, incensed beyond measure at the faithful manner in which Blundell was carrying out his instructions. “He pushed me in.”

There was an angry murmur from the bystanders. “Be reasonable, Mr. Turnbull,” said the sergeant, somewhat sharply.

“He nearly lost ‘is life over you,” said the stout fisherman. “As plucky a thing as ever I see. If I ‘adn’t ha’ been ‘andy with that there line you’d both ha’ been drownded.”

“Give—my love—to everybody,” said Blundell, faintly. “Good-bye, Venia. Good-bye, Mr. Turnbull.”

“Where’s that barrel?” demanded the stout fisher-man, crisply. “Going to be all night with it? Now, two of you——”

Mr. Blundell, with a great effort, and assisted by Venia and the sergeant, sat up. He felt that he had made a good impression, and had no desire to spoil it by riding the barrel. With one exception, everybody was regarding him with moist-eyed admiration. The exception’s eyes were, perhaps, the moistest of them all, but admiration had no place in them.

“You’re all being made fools of,” he said, getting up and stamping. “I tell you he pushed me over-board for the purpose.”

“Oh, father! how can you?” demanded Venia, angrily. “He saved your life.”

“He pushed me in,” repeated the farmer. “Told me to look at a jelly-fish and pushed me in.”

“What for?” inquired Sergeant Daly.

“Because—” said Mr. Turnbull. He looked at the unconscious sergeant, and the words on his lips died away in an inarticulate growl.

“What for?” pursued the sergeant, in triumph. “Be reasonable, Mr. Turnbull. Where’s the reason in pushing you overboard and then nearly losing his life saving you? That would be a fool’s trick. It was as fine a thing as ever I saw.”

“What you ‘ad, Mr. Turnbull,” said the stout fisherman, tapping him on the arm, “was a little touch o’ the sun.”

“What felt to you like a push,” said another man, “and over you went.”

“As easy as easy,” said a third.

“You’re red in the face now,” said the stout fisherman, regarding him critically, “and your eyes are starting. You take my advice and get ‘ome and get to bed, and the first thing you’ll do when you get your senses back will be to go round and thank Mr. Blundell for all ‘e’s done for you.”

Mr. Turnbull looked at them, and the circle of intelligent faces grew misty before his angry eyes. One man, ignoring his sodden condition, recommended a wet handkerchief tied round his brow.

“I don’t want any thanks, Mr. Turnbull,” said Blundell, feebly, as he was assisted to his feet. “I’d do as much for you again.”

The stout fisherman patted him admiringly on the back, and Mr. Turnbull felt like a prophet beholding a realised vision as the spectators clustered round Mr. Blundell and followed their friends’ example. Tenderly but firmly they led the hero in triumph up the quay toward home, shouting out eulogistic descriptions of his valour to curious neighbours as they passed. Mr. Turnbull, churlishly keeping his distance in the rear of the procession, received in grim silence the congratulations of his friends.

The extraordinary hallucination caused by the sun-stroke lasted with him for over a week, but at the end of that time his mind cleared and he saw things in the same light as reasonable folk. Venia was the first to congratulate him upon his recovery; but his extraordinary behaviour in proposing to Miss Sippet the very day on which she herself became Mrs. Blundell convinced her that his recovery was only partial.

BILL’S LAPSE

Strength and good-nature—said the night-watchman, musingly, as he felt his biceps—strength and good-nature always go together. Sometimes you find a strong man who is not good-natured, but then, as everybody he comes in contack with is, it comes to the same thing.

The strongest and kindest-’earted man I ever come across was a man o’ the name of Bill Burton, a ship-mate of Ginger Dick’s. For that matter ‘e was a shipmate o’ Peter Russet’s and old Sam Small’s too. Not over and above tall; just about my height, his arms was like another man’s legs for size, and ‘is chest and his back and shoulders might ha’ been made for a giant. And with all that he’d got a soft blue eye like a gal’s (blue’s my favourite colour for gals’ eyes), and a nice, soft, curly brown beard. He was an A.B., too, and that showed ‘ow good-natured he was, to pick up with firemen.

He got so fond of ‘em that when they was all paid off from the Ocean King he asked to be allowed to join them in taking a room ashore. It pleased every-body, four coming cheaper than three, and Bill being that good-tempered that ‘e’d put up with anything, and when any of the three quarrelled he used to act the part of peacemaker.

The only thing about ‘im that they didn’t like was that ‘e was a teetotaler. He’d go into public-’ouses with ‘em, but he wouldn’t drink; leastways, that is to say, he wouldn’t drink beer, and Ginger used to say that it made ‘im feel uncomfortable to see Bill put away a bottle o’ lemonade every time they ‘ad a drink. One night arter ‘e had ‘ad seventeen bottles he could ‘ardly got home, and Peter Russet, who knew a lot about pills and such-like, pointed out to ‘im ‘ow bad it was for his constitushon. He proved that the lemonade would eat away the coats o’ Bill’s stomach, and that if ‘e kept on ‘e might drop down dead at any moment.

That frightened Bill a bit, and the next night, instead of ‘aving lemonade, ‘e had five bottles o’ stone ginger-beer, six of different kinds of teetotal beer, three of soda-water, and two cups of coffee. I’m not counting the drink he ‘ad at the chemist’s shop arterward, because he took that as medicine, but he was so queer in ‘is inside next morning that ‘e began to be afraid he’d ‘ave to give up drink altogether.

He went without the next night, but ‘e was such a generous man that ‘e would pay every fourth time, and there was no pleasure to the other chaps to see ‘im pay and ‘ave nothing out of it. It spoilt their evening, and owing to ‘aving only about ‘arf wot they was accustomed to they all got up very disagreeable next morning.

“Why not take just a little beer, Bill?” asks Ginger.

Bill ‘ung his ‘ead and looked a bit silly. “I’d rather not, mate,” he ses, at last. “I’ve been teetotal for eleven months now.”

“Think of your ‘ealth, Bill,” ses Peter Russet; “your ‘ealth is more important than the pledge. Wot made you take it?”

Bill coughed. “I ‘ad reasons,” he ses, slowly. “A mate o’ mine wished me to.”

“He ought to ha’ known better,” ses Sam. “He ‘ad ‘is reasons,” ses Bill.

“Well, all I can say is, Bill,” ses Ginger, “all I can say is, it’s very disobligin’ of you.”

“Disobligin’?” ses Bill, with a start; “don’t say that, mate.”

“I must say it,” ses Ginger, speaking very firm.

“You needn’t take a lot, Bill,” ses Sam; “nobody wants you to do that. Just drink in moderation, same as wot we do.”

“It gets into my ‘ead,” ses Bill, at last.

“Well, and wot of it?” ses Ginger; “it gets into everybody’s ‘ead occasionally. Why, one night old Sam ‘ere went up behind a policeman and tickled ‘im under the arms; didn’t you, Sam?”

“I did nothing o’ the kind,” ses Sam, firing up.

“Well, you was fined ten bob for it next morning, that’s all I know,” ses Ginger.

“I was fined ten bob for punching ‘im,” ses old Sam, very wild. “I never tickled a policeman in my life. I never thought o’ such a thing. I’d no more tickle a policeman than I’d fly. Anybody that ses I did is a liar. Why should I? Where does the sense come in? Wot should I want to do it for?”

“All right, Sam,” ses Ginger, sticking ‘is fingers in ‘is ears, “you didn’t, then.”

“No, I didn’t,” ses Sam, “and don’t you forget it. This ain’t the fust time you’ve told that lie about me. I can take a joke with any man; but anybody that goes and ses I tickled—”

“All right,” ses Ginger and Peter Russet together. “You’ll ‘ave tickled policeman on the brain if you ain’t careful, Sam,” ses Peter.

Old Sam sat down growling, and Ginger Dick turned to Bill agin. “It gets into everybody’s ‘ead at times,” he ses, “and where’s the ‘arm? It’s wot it was meant for.”

Bill shook his ‘ead, but when Ginger called ‘im disobligin’ agin he gave way and he broke the pledge that very evening with a pint o’ six ‘arf.

Ginger was surprised to see the way ‘e took his liquor. Arter three or four pints he’d expected to see ‘im turn a bit silly, or sing, or do something o’ the kind, but Bill kept on as if ‘e was drinking water.

“Think of the ‘armless pleasure you’ve been losing all these months, Bill,” ses Ginger, smiling at him.

Bill said it wouldn’t bear thinking of, and, the next place they came to he said some rather ‘ard things of the man who’d persuaded ‘im to take the pledge. He ‘ad two or three more there, and then they began to see that it was beginning to have an effect on ‘im. The first one that noticed it was Ginger Dick. Bill ‘ad just lit ‘is pipe, and as he threw the match down he ses: “I don’t like these ‘ere safety matches,” he ses.

“Don’t you, Bill?” ses Ginger. “I do, rather.”

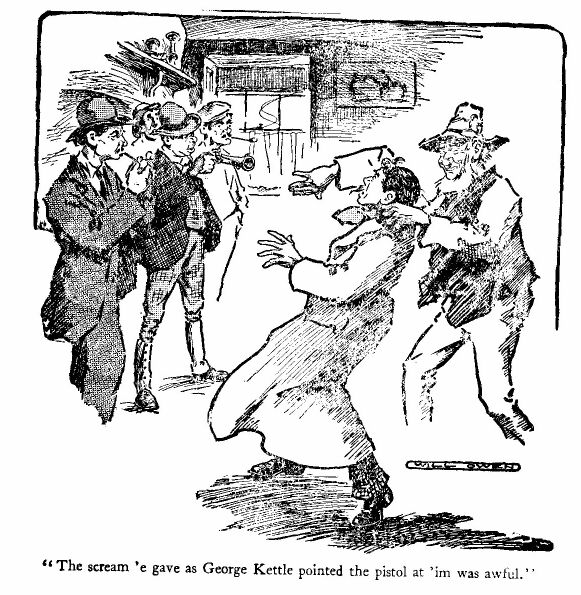

“Oh, you do, do you?” ses Bill, turning on ‘im like lightning; “well, take that for contradictin’,” he ses, an’ he gave Ginger a smack that nearly knocked his ‘ead off.

It was so sudden that old Sam and Peter put their beer down and stared at each other as if they couldn’t believe their eyes. Then they stooped down and helped pore Ginger on to ‘is legs agin and began to brush ‘im down.

“Never mind about ‘im, mates,” ses Bill, looking at Ginger very wicked. “P’r’aps he won’t be so ready to give me ‘is lip next time. Let’s come to another pub and enjoy ourselves.”

Sam and Peter followed ‘im out like lambs, ‘ardly daring to look over their shoulder at Ginger, who was staggering arter them some distance behind a ‘olding a handerchief to ‘is face.

“It’s your turn to pay, Sam,” ses Bill, when they’d got inside the next place. “Wot’s it to be? Give it a name.”

“Three ‘arf pints o’ four ale, miss,” ses Sam, not because ‘e was mean, but because it wasn’t ‘is turn. “Three wot?” ses Bill, turning on ‘im.

“Three pots o’ six ale, miss,” ses Sam, in a hurry.

“That wasn’t wot you said afore,” ses Bill. “Take that,” he ses, giving pore old Sam a wipe in the mouth and knocking ‘im over a stool; “take that for your sauce.”