CAPTAINS ALL

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: Project Gutenberg, Captains All, by W.W. Jacobs

Author: W.W. Jacobs

Release Date: October 30, 2006 [EBook #11191]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CAPTAINS ALL, COMPLETE ***

Produced by David Widger.

――――

CONTENTS

――――

――――

CAPTAINS ALL

Every sailorman grumbles about the sea, said the night-watchman, thoughtfully. It’s human nature to grumble, and I s’pose they keep on grumbling and sticking to it because there ain’t much else they can do. There’s not many shore-going berths that a sailorman is fit for, and those that they are—such as a night-watchman’s, for instance—wants such a good character that there’s few as are to equal it.

Sometimes they get things to do ashore. I knew one man that took up butchering, and ‘e did very well at it till the police took him up. Another man I knew gave up the sea to marry a washerwoman, and they hadn’t been married six months afore she died, and back he ‘ad to go to sea agin, pore chap.

A man who used to grumble awful about the sea was old Sam Small—a man I’ve spoke of to you before. To hear ‘im go on about the sea, arter he ‘ad spent four or five months’ money in a fortnight, was ‘artbreaking. He used to ask us wot was going to happen to ‘im in his old age, and when we pointed out that he wouldn’t be likely to ‘ave any old age if he wasn’t more careful of ‘imself he used to fly into a temper and call us everything ‘e could lay his tongue to.

One time when ‘e was ashore with Peter Russet and Ginger Dick he seemed to ‘ave got it on the brain. He started being careful of ‘is money instead o’ spending it, and three mornings running he bought a newspaper and read the advertisements, to see whether there was any comfortable berth for a strong, good-’arted man wot didn’t like work.

He actually went arter one situation, and, if it hadn’t ha’ been for seventy-nine other men, he said he believed he’d ha’ had a good chance of getting it. As it was, all ‘e got was a black eye for shoving another man, and for a day or two he was so down-’arted that ‘e was no company at all for the other two.

For three or four days ‘e went out by ‘imself, and then, all of a sudden, Ginger Dick and Peter began to notice a great change in him. He seemed to ‘ave got quite cheerful and ‘appy. He answered ‘em back pleasant when they spoke to ‘im, and one night he lay in ‘is bed whistling comic songs until Ginger and Peter Russet ‘ad to get out o’ bed to him. When he bought a new necktie and a smart cap and washed ‘imself twice in one day they fust began to ask each other wot was up, and then they asked him.

“Up?” ses Sam; “nothing.”

“He’s in love,” ses Peter Russet.

“You’re a liar,” ses Sam, without turning round.

“He’ll ‘ave it bad at ‘is age,” ses Ginger.

Sam didn’t say nothing, but he kept fidgeting about as though ‘e’d got something on his mind. Fust he looked out o’ the winder, then he ‘ummed a tune, and at last, looking at ‘em very fierce, he took a tooth-brush wrapped in paper out of ‘is pocket and began to clean ‘is teeth.

“He is in love,” ses Ginger, as soon as he could speak.

“Or else ‘e’s gorn mad,” ses Peter, watching ‘im. “Which is it, Sam?”

Sam made believe that he couldn’t answer ‘im because o’ the tooth-brush, and arter he’d finished he ‘ad such a raging toothache that ‘e sat in a corner holding ‘is face and looking the pictur’ o’ misery. They couldn’t get a word out of him till they asked ‘im to go out with them, and then he said ‘e was going to bed. Twenty minutes arterwards, when Ginger Dick stepped back for ‘is pipe, he found he ‘ad gorn.

He tried the same game next night, but the other two wouldn’t ‘ave it, and they stayed in so long that at last ‘e lost ‘is temper, and, arter wondering wot Ginger’s father and mother could ha’ been a-thinking about, and saying that he believed Peter Russet ‘ad been changed at birth for a sea-sick monkey, he put on ‘is cap and went out. Both of ‘em follered ‘im sharp, but when he led ‘em to a mission-hall, and actually went inside, they left ‘im and went off on their own.

They talked it over that night between themselves, and next evening they went out fust and hid themselves round the corner. Ten minutes arterwards old Sam came out, walking as though ‘e was going to catch a train; and smiling to think ‘ow he ‘ad shaken them off. At the corner of Commercial Road he stopped and bought ‘imself a button-hole for ‘is coat, and Ginger was so surprised that ‘e pinched Peter Russet to make sure that he wasn’t dreaming.

Old Sam walked straight on whistling, and every now and then looking down at ‘is button-hole, until by-and-by he turned down a street on the right and went into a little shop. Ginger Dick and Peter waited for ‘im at the corner, but he was inside for so long that at last they got tired o’ waiting and crept up and peeped through the winder.

It was a little tobacconist’s shop, with newspapers and penny toys and such-like; but, as far as Ginger could see through two rows o’ pipes and the Police News, it was empty. They stood there with their noses pressed against the glass for some time, wondering wot had ‘appened to Sam, but by-and-by a little boy went in and then they began to ‘ave an idea wot Sam’s little game was.

As the shop-bell went the door of a little parlour at the back of the shop opened, and a stout and uncommon good-looking woman of about forty came out. Her ‘ead pushed the Police News out o’ the way and her ‘and came groping into the winder arter a toy.

Ginger ‘ad a good look at ‘er out o’ the corner of one eye, while he pretended to be looking at a tobacco-jar with the other. As the little boy came out ‘im and Peter Russet went in.

“I want a pipe, please,” he ses, smiling at ‘er; “a clay pipe—one o’ your best.” The woman handed ‘im down a box to choose from, and just then Peter, wot ‘ad been staring in at the arf-open door at a boot wot wanted lacing up, gave a big start and ses, “Why! Halloa!”

“Wot’s the matter?” ses the woman, looking at ‘im.

“I’d know that foot anywhere,” ses Peter, still staring at it; and the words was hardly out of ‘is mouth afore the foot ‘ad moved itself away and tucked itself under its chair. “Why, that’s my dear old friend Sam Small, ain’t it?”

“Do you know the captin?” ses the woman, smiling at ‘im.

“Cap——?” ses Peter. “Cap——? Oh, yes; why, he’s the biggest friend I’ve got.” “‘Ow strange!” ses the woman.

“We’ve been wanting to see ‘im for some time,” ses Ginger. “He was kind enough to lend me arf a crown the other day, and I’ve been wanting to pay ‘im.”

“Captin Small,” ses the woman, pushing open the door, “here’s some old friends o’ yours.”

Old Sam turned ‘is face round and looked at ‘em, and if looks could ha’ killed, as the saying is, they’d ha’ been dead men there and then.

“Oh, yes,” he ses, in a choking voice; “‘ow are you?”

“Pretty well, thank you, captin,” ses Ginger, grinning at ‘im; “and ‘ow’s yourself arter all this long time?”

He held out ‘is hand and Sam shook it, and then shook ‘ands with Peter Russet, who was grinning so ‘ard that he couldn’t speak.

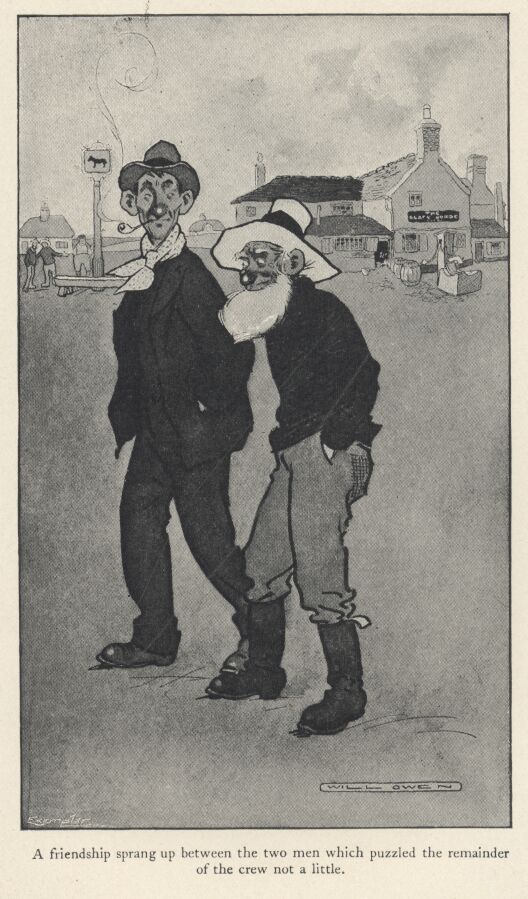

“These are two old friends o’ mine, Mrs. Finch,” ses old Sam, giving ‘em a warning look; “Captin Dick and Captin Russet, two o’ the oldest and best friends a man ever ‘ad.”

“Captin Dick ‘as got arf a crown for you,” ses Peter Russet, still grinning.

“There now,” ses Ginger, looking vexed, “if I ain’t been and forgot it; I’ve on’y got arf a sovereign.”

“I can give you change, sir,” ses Mrs. Finch. “P’r’aps you’d like to sit down for five minutes?”

Ginger thanked ‘er, and ‘im and Peter Russet took a chair apiece in front o’ the fire and began asking old Sam about ‘is ‘ealth, and wot he’d been doing since they saw ‘im last.

“Fancy your reckernizing his foot,” ses Mrs. Finch, coming in with the change.

“I’d know it anywhere,” ses Peter, who was watching Ginger pretending to give Sam Small the ‘arf-dollar, and Sam pretending in a most lifelike manner to take it.

Ginger Dick looked round the room. It was a comfortable little place, with pictures on the walls and antimacassars on all the chairs, and a row of pink vases on the mantelpiece. Then ‘e looked at Mrs. Finch, and thought wot a nice-looking woman she was.

“This is nicer than being aboard ship with a crew o’ nasty, troublesome sailormen to look arter, Captin Small,” he ses.

“It’s wonderful the way he manages ‘em,” ses Peter Russet to Mrs. Finch. “Like a lion he is.”

“A roaring lion,” ses Ginger, looking at Sam. “He don’t know wot fear is.”

Sam began to smile, and Mrs. Finch looked at ‘im so pleased that Peter Russet, who ‘ad been looking at ‘er and the room, and thinking much the same way as Ginger, began to think that they was on the wrong tack.

“Afore ‘e got stout and old,” he ses, shaking his ‘ead, “there wasn’t a smarter skipper afloat.”

“We all ‘ave our day,” ses Ginger, shaking his ‘ead too.

“I dessay he’s good for another year or two afloat, yet,” ses Peter Russet, considering. “With care,” ses Ginger.

Old Sam was going to say something, but ‘e stopped himself just in time. “They will ‘ave their joke,” he ses, turning to Mrs. Finch and trying to smile. “I feel as young as ever I did.”

Mrs. Finch said that anybody with arf an eye could see that, and then she looked at a kettle that was singing on the ‘ob.

“I s’pose you gentlemen wouldn’t care for a cup o’ cocoa?” she ses, turning to them.

Ginger Dick and Peter both said that they liked it better than anything else, and, arter she ‘ad got out the cups and saucers and a tin o’ cocoa, Ginger held the kettle and poured the water in the cups while she stirred them, and old Sam sat looking on ‘elpless.

“It does seem funny to see you drinking cocoa, captin,” ses Ginger, as old Sam took his cup.

“Ho!” ses Sam, firing up; “and why, if I might make so bold as to ask?”

“‘Cos I’ve generally seen you drinking something out of a bottle,” ses Ginger.

“Now, look ‘ere,” ses Sam, starting up and spilling some of the hot cocoa over ‘is lap.

“A ginger-beer bottle,” ses Peter Russet, making faces at Ginger to keep quiet.

“Yes, o’ course, that’s wot I meant,” ses Ginger.

Old Sam wiped the cocoa off ‘is knees without saying a word, but his weskit kept going up and down till Peter Russet felt quite sorry for ‘im.

“There’s nothing like it,” he ses to Mrs. Finch. “It was by sticking to ginger-beer and milk and such-like that Captain Small ‘ad command of a ship afore ‘e was twenty-five.”

“Lor’!” ses Mrs. Finch.

She smiled at old Sam till Peter got uneasy agin, and began to think p’r’aps ‘e’d been praising ‘im too much.

“Of course, I’m speaking of long ago now,” he ses.

“Years and years afore you was born, ma’am,” ses Ginger.

Old Sam was going to say something, but Mrs. Finch looked so pleased that ‘e thought better of it. Some o’ the cocoa ‘e was drinking went the wrong way, and then Ginger patted ‘im on the back and told ‘im to be careful not to bring on ‘is brownchitis agin. Wot with temper and being afraid to speak for fear they should let Mrs. Finch know that ‘e wasn’t a captin, he could ‘ardly bear ‘imself, but he very near broke out when Peter Russet advised ‘im to ‘ave his weskit lined with red flannel. They all stayed on till closing time, and by the time they left they ‘ad made theirselves so pleasant that Mrs. Finch said she’d be pleased to see them any time they liked to look in.

Sam Small waited till they ‘ad turned the corner, and then he broke out so alarming that they could ‘ardly do anything with ‘im. Twice policemen spoke to ‘im and advised ‘im to go home afore they altered their minds; and he ‘ad to hold ‘imself in and keep quiet while Ginger and Peter Russet took ‘is arms and said they were seeing him ‘ome.

He started the row agin when they got in-doors, and sat up in ‘is bed smacking ‘is lips over the things he’d like to ‘ave done to them if he could. And then, arter saying ‘ow he’d like to see Ginger boiled alive like a lobster, he said he knew that ‘e was a noble-’arted feller who wouldn’t try and cut an old pal out, and that it was a case of love at first sight on top of a tram-car.

“She’s too young for you,” ses Ginger; “and too good-looking besides.”

“It’s the nice little bisness he’s fallen in love with, Ginger,” ses Peter Russet. “I’ll toss you who ‘as it.”

Ginger, who was siting on the foot o’ Sam’s bed, said “no” at fust, but arter a time he pulled out arf a dollar and spun it in the air.

That was the last ‘e see of it, although he ‘ad Sam out o’ bed and all the clothes stripped off of it twice. He spent over arf an hour on his ‘ands and knees looking for it, and Sam said when he was tired of playing bears p’r’aps he’d go to bed and get to sleep like a Christian.

They ‘ad it all over agin next morning, and at last, as nobody would agree to keep quiet and let the others ‘ave a fair chance, they made up their minds to let the best man win. Ginger Dick bought a necktie that took all the colour out o’ Sam’s, and Peter Russet went in for a collar so big that ‘e was lost in it.

They all strolled into the widow’s shop separate that night. Ginger Dick ‘ad smashed his pipe and wanted another; Peter Russet wanted some tobacco; and old Sam Small walked in smiling, with a little silver brooch for ‘er, that he said ‘e had picked up.

It was a very nice brooch, and Mrs. Finch was so pleased with it that Ginger and Peter sat there as mad as they could be because they ‘adn’t thought of the same thing.

“Captain Small is very lucky at finding things,” ses Ginger, at last.

“He’s got the name for it,” ses Peter Russet.

“It’s a handy ‘abit,” ses Ginger; “it saves spending money. Who did you give that gold bracelet to you picked up the other night, captin?” he ses, turning to Sam.

“Gold bracelet?” ses Sam. “I didn’t pick up no gold bracelet. Wot are you talking about?”

“All right, captin; no offence,” ses Ginger, holding up his ‘and. “I dreamt I saw one on your mantelpiece, I s’pose. P’r’aps I oughtn’t to ha’ said anything about it.”

Old Sam looked as though he’d like to eat ‘im, especially as he noticed Mrs. Finch listening and pretending not to. “Oh! that one,” he ses, arter a bit o’ hard thinking. “Oh! I found out who it belonged to. You wouldn’t believe ‘ow pleased they was at getting it back agin.”

Ginger Dick coughed and began to think as ‘ow old Sam was sharper than he ‘ad given ‘im credit for, but afore he could think of anything else to say Mrs. Finch looked at old Sam and began to talk about ‘is ship, and to say ‘ow much she should like to see over it.

“I wish I could take you,” ses Sam, looking at the other two out o’ the corner of his eye, “but my ship’s over at Dunkirk, in France. I’ve just run over to London for a week or two to look round.”

“And mine’s there too,” ses Peter Russet, speaking a’most afore old Sam ‘ad finished; “side by side they lay in the harbour.”

“Oh, dear,” ses Mrs. Finch, folding her ‘ands and shaking her ‘cad. “I should like to go over a ship one arternoon. I’d quite made up my mind to it, knowing three captins.”

She smiled and looked at Ginger; and Sam and Peter looked at ‘im too, wondering whether he was going to berth his ship at Dunkirk alongside o’ theirs.

“Ah, I wish I ‘ad met you a fortnight ago,” ses Ginger, very sad. “I gave up my ship, the High flyer, then, and I’m waiting for one my owners are ‘aving built for me at New-castle. They said the High flyer wasn’t big enough for me. She was a nice little ship, though. I believe I’ve got ‘er picture somewhere about me!”

He felt in ‘is pocket and pulled out a little, crumpled-up photograph of a ship he’d been fireman aboard of some years afore, and showed it to ‘er.

“That’s me standing on the bridge,” he ses, pointing out a little dot with the stem of ‘is pipe.

“It’s your figger,” ses Mrs. Finch, straining her eyes. “I should know it anywhere.”

“You’ve got wonderful eyes, ma’am,” ses old Sam, choking with ‘is pipe.

“Anybody can see that,” ses Ginger. “They’re the largest and the bluest I’ve ever seen.”

Mrs. Finch told ‘im not to talk nonsense, but both Sam and Peter Russet could see ‘ow pleased she was.

“Truth is truth,” ses Ginger. “I’m a plain man, and I speak my mind.”

“Blue is my fav’rit’ colour,” ses old Sam, in a tender voice. “True blue.”

Peter Russet began to feel out of it. “I thought brown was,” he ses.

“Ho!” ses Sam, turning on ‘im; “and why?”

“I ‘ad my reasons,” ses Peter, nodding, and shutting ‘is mouth very firm.

“I thought brown was ‘is fav’rit colour too,” ses Ginger. “I don’t know why. It’s no use asking me; because if you did I couldn’t tell you.”

“Brown’s a very nice colour,” ses Mrs. Finch, wondering wot was the matter with old Sam.

“Blue,” ses Ginger; “big blue eyes—they’re the ones for me. Other people may ‘ave their blacks and their browns,” he ses, looking at Sam and Peter Russet, “but give me blue.”

They went on like that all the evening, and every time the shop-bell went and the widow ‘ad to go out to serve a customer they said in w’ispers wot they thought of each other; and once when she came back rather sudden Ginger ‘ad to explain to ‘er that ‘e was showing Peter Russet a scratch on his knuckle.

Ginger Dick was the fust there next night, and took ‘er a little chiney teapot he ‘ad picked up dirt cheap because it was cracked right acrost the middle; but, as he explained that he ‘ad dropped it in hurrying to see ‘er, she was just as pleased. She stuck it up on the mantelpiece, and the things she said about Ginger’s kindness and generosity made Peter Russet spend good money that he wanted for ‘imself on a painted flower-pot next evening.

With three men all courting ‘er at the same time Mrs. Finch had ‘er hands full, but she took to it wonderful considering. She was so nice and kind to ‘em all that even arter a week’s ‘ard work none of ‘em was really certain which she liked best.

They took to going in at odd times o’ the day for tobacco and such-like. They used to go alone then, but they all met and did the polite to each other there of an evening, and then quarrelled all the way ‘ome.

Then all of a sudden, without any warning, Ginger Dick and Peter Russet left off going there. The fust evening Sam sat expecting them every minute, and was so surprised that he couldn’t take any advantage of it; but on the second, beginning by squeezing Mrs. Finch’s ‘and at ha’-past seven, he ‘ad got best part of his arm round ‘er waist by a quarter to ten. He didn’t do more that night because she told him to be’ave ‘imself, and threatened to scream if he didn’t leave off.

He was arf-way home afore ‘e thought of the reason for Ginger Dick and Peter Russet giving up, and then he went along smiling to ‘imself to such an extent that people thought ‘e was mad. He went off to sleep with the smile still on ‘is lips, and when Peter and Ginger came in soon arter closing time and ‘e woke up and asked them where they’d been, ‘e was still smiling.

“I didn’t ‘ave the pleasure o’ seeing you at Mrs. Finch’s to-night,” he ses.

“No,” ses Ginger, very short. “We got tired of it.”

“So un’ealthy sitting in that stuffy little room every evening,” ses Peter.

Old Sam put his ‘ead under the bedclothes and laughed till the bed shook; and every now and then he’d put his ‘ead out and look at Peter and Ginger and laugh agin till he choked.

“I see ‘ow it is,” he ses, sitting up and wiping his eyes on the sheet. “Well, we cant all win.”

“Wot d’ye mean?” ses Ginger, very disagreeable.

“She wouldn’t ‘ave you, Sam, thats wot I mean. And I don’t wonder at it. I wouldn’t ‘ave you if I was a gal.”

“You’re dreaming, ses Peter Russet, sneering at ‘im.

“That flower-pot o’ yours’ll come in handy,” ses Sam, thinking ‘ow he ‘ad put ‘is arm round the widow’s waist; “and I thank you kindly for the teapot, Ginger.

“You don’t mean to say as you’ve asked ‘er to marry you?” ses Ginger, looking at Peter Russet.

“Not quite; but I’m going to,” ses Sam, “and I’ll bet you even arf-crowns she ses ‘yes.’”

Ginger wouldn’t take ‘im, and no more would Peter, not even when he raised it to five shillings; and the vain way old Sam lay there boasting and talking about ‘is way with the gals made ‘em both feel ill.

“I wouldn’t ‘ave her if she asked me on ‘er bended knees,” ses Ginger, holding up his ‘ead.

“Nor me,” ses Peter. “You’re welcome to ‘er, Sam. When I think of the evenings I’ve wasted over a fat old woman I feel——”

“That’ll do,” ses old Sam, very sharp; “that ain’t the way to speak of a lady, even if she ‘as said ‘no.’”

“All right, Sam,” ses Ginger. “You go in and win if you think you’re so precious clever.”

Old Sam said that that was wot ‘e was going to do, and he spent so much time next morning making ‘imself look pretty that the other two could ‘ardly be civil to him.

He went off a’most direckly arter breakfast, and they didn’t see ‘im agin till twelve o’clock that night. He ‘ad brought a bottle o’ whisky in with ‘im, and he was so ‘appy that they see plain wot had ‘appened.

“She said ‘yes’ at two o’clock in the arternoon,” ses old Sam, smiling, arter they had ‘ad a glass apiece. “I’d nearly done the trick at one o’clock, and then the shop-bell went, and I ‘ad to begin all over agin. Still, it wasn’t unpleasant.”

“Do you mean to tell us you’ve asked ‘er to marry you?” ses Ginger, ‘olding out ‘is glass to be filled agin.

“I do,” ses Sam; “but I ‘ope there’s no ill-feeling. You never ‘ad a chance, neither of you; she told me so.”

Ginger Dick and Peter Russet stared at each other.

“She said she ‘ad been in love with me all along,” ses Sam, filling their glasses agin to cheer ‘em up. “We went out arter tea and bought the engagement-ring, and then she got somebody to mind the shop and we went to the Pagoda music-’all.”

“I ‘ope you didn’t pay much for the ring, Sam,” ses Ginger, who always got very kind-’arted arter two or three glasses o’ whisky. “If I’d known you was going to be in such a hurry I might ha’ told you before.”

“We ought to ha’ done,” ses Peter, shaking his ‘ead.

“Told me?” ses Sam, staring at ‘em. “Told me wot?”

“Why me and Peter gave it up,” ses Ginger; “but, o’ course, p’r’aps you don’t mind.”

“Mind wot?” ses Sam.

“It’s wonderful ‘ow quiet she kept it,” ses Peter.

Old Sam stared at ‘em agin, and then he asked ‘em to speak in plain English wot they’d got to say, and not to go taking away the character of a woman wot wasn’t there to speak up for herself.

“It’s nothing agin ‘er character,” ses Ginger. “It’s a credit to her, looked at properly,” ses Peter Russet.

“And Sam’ll ‘ave the pleasure of bringing of ‘em up,” ses Ginger.

“Bringing of ‘em up?” ses Sam, in a trembling voice and turning pale; “bringing who up?”

“Why, ‘er children,” ses Ginger. “Didn’t she tell you? She’s got nine of ‘em.”

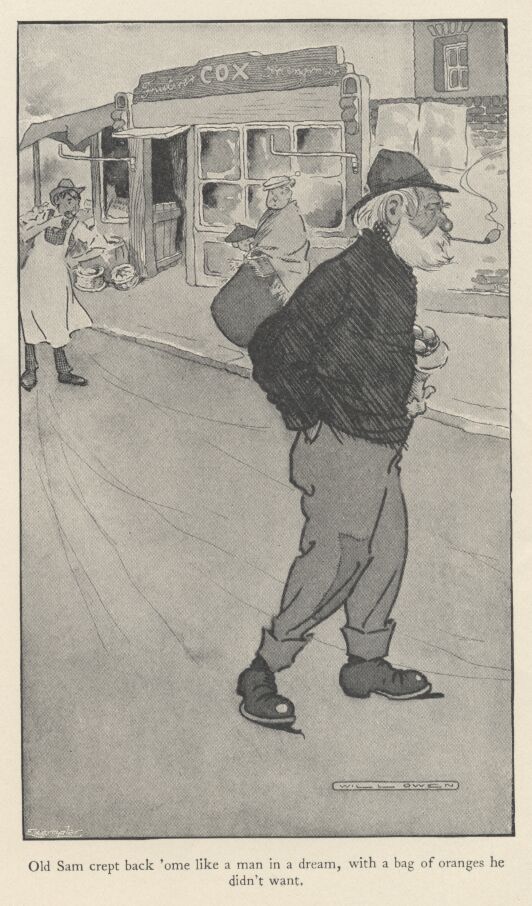

Sam pretended not to believe ‘em at fust, and said they was jealous; but next day he crept down to the greengrocer’s shop in the same street, where Ginger had ‘appened to buy some oranges one day, and found that it was only too true. Nine children, the eldest of ‘em only fifteen, was staying with diff’rent relations owing to scarlet-fever next door.

Old Sam crept back ‘ome like a man in a dream, with a bag of oranges he didn’t want, and, arter making a present of the engagement-ring to Ginger—if ‘e could get it—he took the fust train to Tilbury and signed on for a v’y’ge to China.

THE BOATSWAIN’S MATE

Mr. George Benn, retired boat-swain, sighed noisily, and with a despondent gesture, turned to the door and stood with the handle in his hand; Mrs. Waters, sitting behind the tiny bar in a tall Windsor-chair, eyed him with some heat.

“My feelings’ll never change,” said the boatswain.

“Nor mine either,” said the landlady, sharply. “It’s a strange thing, Mr. Benn, but you always ask me to marry you after the third mug.”

“It’s only to get my courage up,” pleaded the boatswain. “Next time I’ll do it afore I ‘ave a drop; that’ll prove to you I’m in earnest.”

He stepped outside and closed the door before the landlady could make a selection from the many retorts that crowded to her lips.

After the cool bar, with its smell of damp saw-dust, the road seemed hot and dusty; but the boatswain, a prey to gloom natural to a man whose hand has been refused five times in a fortnight, walked on unheeding. His steps lagged, but his brain was active.

He walked for two miles deep in thought, and then coming to a shady bank took a seat upon an inviting piece of turf and lit his pipe. The heat and the drowsy hum of bees made him nod; his pipe hung from the corner of his mouth, and his eyes closed.

He opened them at the sound of approaching footsteps, and, feeling in his pocket for matches, gazed lazily at the intruder. He saw a tall man carrying a small bundle over his shoulder, and in the erect carriage, the keen eyes, and bronzed face had little difficulty in detecting the old soldier.

The stranger stopped as he reached the seated boatswain and eyed him pleasantly.

“Got a pipe o’ baccy, mate?” he inquired.

The boatswain handed him the small metal box in which he kept that luxury.

“Lobster, ain’t you?” he said, affably.

The tall man nodded. “Was,” he replied. “Now I’m my own commander-in-chief.”

“Padding it?” suggested the boatswain, taking the box from him and refilling his pipe.

The other nodded, and with the air of one disposed to conversation dropped his bundle in the ditch and took a seat beside him. “I’ve got plenty of time,” he remarked.

Mr. Benn nodded, and for a while smoked on in silence. A dim idea which had been in his mind for some time began to clarify. He stole a glance at his companion—a man of about thirty-eight, clear eyes, with humorous wrinkles at the corners, a heavy moustache, and a cheerful expression more than tinged with recklessness.

“Ain’t over and above fond o’ work?” suggested the boatswain, when he had finished his inspection.

“I love it,” said the other, blowing a cloud of smoke in the air, “but we can’t have all we want in this world; it wouldn’t be good for us.”

The boatswain thought of Mrs. Waters, and sighed. Then he rattled his pocket.

“Would arf a quid be any good to you?” he inquired.

“Look here,” began the soldier; “just because I asked you for a pipe o’ baccy—”

“No offence,” said the other, quickly. “I mean if you earned it?”

The soldier nodded and took his pipe from his mouth. “Gardening and windows?” he hazarded, with a shrug of his shoulders.

The boatswain shook his head.

“Scrubbing, p’r’aps?” said the soldier, with a sigh of resignation. “Last house I scrubbed out I did it so thoroughly they accused me of pouching the soap. Hang ‘em!”

“And you didn’t?” queried the boatswain, eyeing him keenly.

The soldier rose and, knocking the ashes out of his pipe, gazed at him darkly. “I can’t give it back to you,” he said, slowly, “because I’ve smoked some of it, and I can’t pay you for it because I’ve only got twopence, and that I want for myself. So long, matey, and next time a poor wretch asks you for a pipe, be civil.”

“I never see such a man for taking offence in all my born days,” expostulated the boat-swain. “I ‘ad my reasons for that remark, mate. Good reasons they was.”

The soldier grunted and, stooping, picked up his bundle.

“I spoke of arf a sovereign just now,” continued the boatswain, impressively, “and when I tell you that I offer it to you to do a bit o’ burgling, you’ll see ‘ow necessary it is for me to be certain of your honesty.”

“Burgling?” gasped the astonished soldier. “Honesty? ‘Struth; are you drunk or am I?”

“Meaning,” said the boatswain, waving the imputation away with his hand, “for you to pretend to be a burglar.”

“We’re both drunk, that’s what it is,” said the other, resignedly.

The boatswain fidgeted. “If you don’t agree, mum’s the word and no ‘arm done,” he said, holding out his hand.

“Mum’s the word,” said the soldier, taking it. “My name’s Ned Travers, and, barring cells for a spree now and again, there’s nothing against it. Mind that.”

“Might ‘appen to anybody,” said Mr. Benn, soothingly. “You fill your pipe and don’t go chucking good tobacco away agin.”

Mr. Travers took the offered box and, with economy born of adversity, stooped and filled up first with the plug he had thrown away. Then he resumed his seat and, leaning back luxuriously, bade the other “fire away.”

“I ain’t got it all ship-shape and proper yet,” said Mr. Benn, slowly, “but it’s in my mind’s eye. It’s been there off and on like for some time.”

He lit his pipe again and gazed fixedly at the opposite hedge. “Two miles from here, where I live,” he said, after several vigorous puffs, “there’s a little public-’ouse called the Beehive, kept by a lady wot I’ve got my eye on.”

The soldier sat up.

“She won’t ‘ave me,” said the boatswain, with an air of mild surprise.

The soldier leaned back again.

“She’s a lone widder,” continued Mr. Benn, shaking his head, “and the Beehive is in a lonely place. It’s right through the village, and the nearest house is arf a mile off.”

“Silly place for a pub,” commented Mr. Travers.

“I’ve been telling her ‘ow unsafe it is,” said the boatswain. “I’ve been telling her that she wants a man to protect her, and she only laughs at me. She don’t believe it; d’ye see? Likewise I’m a small man—small, but stiff. She likes tall men.”

“Most women do,” said Mr. Travers, sitting upright and instinctively twisting his moustache. “When I was in the ranks—”

“My idea is,” continued the boatswain, slightly raising his voice, “to kill two birds with one stone—prove to her that she does want being protected, and that I’m the man to protect her. D’ye take my meaning, mate?”

The soldier reached out a hand and felt the other’s biceps. “Like a lump o’ wood,” he said, approvingly.

“My opinion is,” said the boatswain, with a faint smirk, “that she loves me without knowing it.”

“They often do,” said Mr. Travers, with a grave shake of his head.

“Consequently I don’t want ‘er to be disappointed,” said the other.

“It does you credit,” remarked Mr. Travers.

“I’ve got a good head,” said Mr. Benn, “else I shouldn’t ‘ave got my rating as boatswain as soon as I did; and I’ve been turning it over in my mind, over and over agin, till my brain-pan fair aches with it. Now, if you do what I want you to to-night and it comes off all right, damme I’ll make it a quid.”

“Go on, Vanderbilt,” said Mr. Travers; “I’m listening.”

The boatswain gazed at him fixedly. “You meet me ‘ere in this spot at eleven o’clock to-night,” he said, solemnly; “and I’ll take you to her ‘ouse and put you through a little winder I know of. You goes upstairs and alarms her, and she screams for help. I’m watching the house, faithful-like, and hear ‘er scream. I dashes in at the winder, knocks you down, and rescues her. D’ye see?”

“I hear,” corrected Mr. Travers, coldly.

“She clings to me,” continued the boat-swain, with a rapt expression of face, “in her gratitood, and, proud of my strength and pluck, she marries me.”

“An’ I get a five years’ honeymoon,” said the soldier.

The boatswain shook his head and patted the other’s shoulder. “In the excitement of the moment you spring up and escape,” he said, with a kindly smile. “I’ve thought it all out. You can run much faster than I can; any-ways, you will. The nearest ‘ouse is arf a mile off, as I said, and her servant is staying till to-morrow at ‘er mother’s, ten miles away.”

Mr. Travers rose to his feet and stretched himself. “Time I was toddling,” he said, with a yawn. “Thanks for amusing me, mate.”

“You won’t do it?” said the boatswain, eyeing him with much concern.

“I’m hanged if I do,” said the soldier, emphatically. “Accidents will happen, and then where should I be?”

“If they did,” said the boatswain, “I’d own up and clear you.”

“You might,” said Mr. Travers, “and then again you mightn’t. So long, mate.”

“I—I’ll make it two quid,” said the boat-swain, trembling with eagerness. “I’ve took a fancy to you; you’re just the man for the job.”

The soldier, adjusting his bundle, glanced at him over his shoulder. “Thankee,” he said, with mock gratitude.

“Look ‘ere,” said the boatswain, springing up and catching him by the sleeve; “I’ll give it to you in writing. Come, you ain’t faint-hearted? Why, a bluejacket ‘ud do it for the fun o’ the thing. If I give it to you in writing, and there should be an accident, it’s worse for me than it is for you, ain’t it?”

Mr. Travers hesitated and, pushing his cap back, scratched his head.

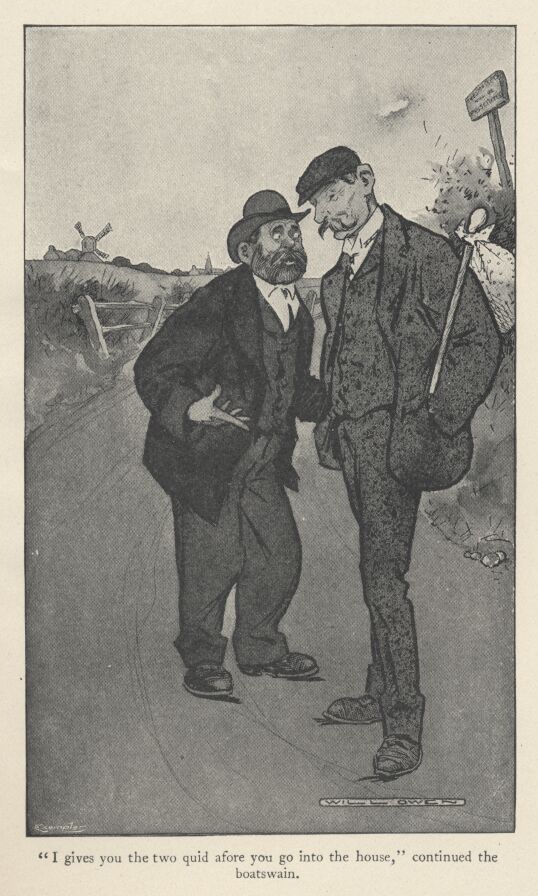

“I gives you the two quid afore you go into the house,” continued the boatswain, hastily following up the impression he had made. “I’d give ‘em to you now if I’d got ‘em with me. That’s my confidence in you; I likes the look of you. Soldier or sailor, when there is a man’s work to be done, give ‘em to me afore anybody.”

The soldier seated himself again and let his bundle fall to the ground. “Go on,” he said, slowly. “Write it out fair and square and sign it, and I’m your man.”

The boatswain clapped him on the shoulder and produced a bundle of papers from his pocket. “There’s letters there with my name and address on ‘em,” he said. “It’s all fair, square, and above-board. When you’ve cast your eyes over them I’ll give you the writing.”

Mr. Travers took them and, re-lighting his pipe, smoked in silence, with various side glances at his companion as that enthusiast sucked his pencil and sat twisting in the agonies of composition. The document finished—after several failures had been retrieved and burnt by the careful Mr. Travers—the boat-swain heaved a sigh of relief, and handing it over to him, leaned back with a complacent air while he read it.

“Seems all right,” said the soldier, folding it up and putting it in his waistcoat-pocket. “I’ll be here at eleven to-night.”

“Eleven it is,” said the boatswain, briskly, “and, between pals—here’s arf a dollar to go on with.”

He patted him on the shoulder again, and with a caution to keep out of sight as much as possible till night walked slowly home. His step was light, but he carried a face in which care and exultation were strangely mingled.

By ten o’clock that night care was in the ascendant, and by eleven, when he discerned the red glow of Mr. Travers’s pipe set as a beacon against a dark background of hedge, the boatswain was ready to curse his inventive powers. Mr. Travers greeted him cheerily and, honestly attributing the fact to good food and a couple of pints of beer he had had since the boatswain left him, said that he was ready for anything.

Mr. Benn grunted and led the way in silence. There was no moon, but the night was clear, and Mr. Travers, after one or two light-hearted attempts at conversation, abandoned the effort and fell to whistling softly instead.

Except for one lighted window the village slept in darkness, but the boatswain, who had been walking with the stealth of a Red Indian on the war-path, breathed more freely after they had left it behind. A renewal of his antics a little farther on apprised Mr. Travers that they were approaching their destination, and a minute or two later they came to a small inn standing just off the road. “All shut up and Mrs. Waters abed, bless her,” whispered the boatswain, after walking care-fully round the house. “How do you feel?”

“I’m all right,” said Mr. Travers. “I feel as if I’d been burgling all my life. How do you feel?”

“Narvous,” said Mr. Benn, pausing under a small window at the rear of the house. “This is the one.”

Mr. Travers stepped back a few paces and gazed up at the house. All was still. For a few moments he stood listening and then re-joined the boatswain.

“Good-bye, mate,” he said, hoisting himself on to the sill. “Death or victory.”

The boatswain whispered and thrust a couple of sovereigns into his hand. “Take your time; there’s no hurry,” he muttered. “I want to pull myself together. Frighten ‘er enough, but not too much. When she screams I’ll come in.”

Mr. Travers slipped inside and then thrust his head out of the window. “Won’t she think it funny you should be so handy?” he inquired.

“No; it’s my faithful ‘art,” said the boat-swain, “keeping watch over her every night, that’s the ticket. She won’t know no better.”

Mr. Travers grinned, and removing his boots passed them out to the other. “We don’t want her to hear me till I’m upstairs,” he whispered. “Put ‘em outside, handy for me to pick up.”

The boatswain obeyed, and Mr. Travers—who was by no means a good hand at darning socks—shivered as he trod lightly over a stone floor. Then, following the instructions of Mr. Benn, he made his way to the stairs and mounted noiselessly.

But for a slight stumble half-way up his progress was very creditable for an amateur. He paused and listened and, all being silent, made his way to the landing and stopped out-side a door. Despite himself his heart was beating faster than usual.

He pushed the door open slowly and started as it creaked. Nothing happening he pushed again, and standing just inside saw, by a small ewer silhouetted against the casement, that he was in a bedroom. He listened for the sound of breathing, but in vain.

“Quiet sleeper,” he reflected; “or perhaps it is an empty room. Now, I wonder whether—”

The sound of an opening door made him start violently, and he stood still, scarcely breathing, with his ears on the alert. A light shone on the landing, and peeping round the door he saw a woman coming along the corridor—a younger and better-looking woman than he had expected to see. In one hand she held aloft a candle, in the other she bore a double-barrelled gun. Mr. Travers withdrew into the room and, as the light came nearer, slipped into a big cupboard by the side of the fireplace and, standing bolt upright, waited. The light came into the room.

“Must have been my fancy,” said a pleasant voice.

“Bless her,” smiled Mr. Travers.

His trained ear recognized the sound of cocking triggers. The next moment a heavy body bumped against the door of the cupboard and the key turned in the lock.

“Got you!” said the voice, triumphantly. “Keep still; if you try and break out I shall shoot you.”

“All right,” said Mr. Travers, hastily; “I won’t move.”

“Better not,” said the voice. “Mind, I’ve got a gun pointing straight at you.”

“Point it downwards, there’s a good girl,” said Mr. Travers, earnestly; “and take your finger off the trigger. If anything happened to me you’d never forgive yourself.”

“It’s all right so long as you don’t move,” said the voice; “and I’m not a girl,” it added, sternly.

“Yes, you are,” said the prisoner. “I saw you. I thought it was an angel at first. I saw your little bare feet and—”

A faint scream interrupted him.

“You’ll catch cold,” urged Mr. Travers.

“Don’t you trouble about me,” said the voice, tartly.

“I won’t give any trouble,” said Mr. Travers, who began to think it was time for the boatswain to appear on the scene. “Why don’t you call for help? I’ll go like a lamb.”

“I don’t want your advice,” was the reply. “I know what to do. Now, don’t you try and break out. I’m going to fire one barrel out of the window, but I’ve got the other one for you if you move.”

“My dear girl,” protested the horrified Mr. Travers, “you’ll alarm the neighbourhood.”

“Just what I want to do,” said the voice. “Keep still, mind.”

Mr. Travers hesitated. The game was up, and it was clear that in any case the stratagem of the ingenious Mr. Benn would have to be disclosed.

“Stop!” he said, earnestly. “Don’t do anything rash. I’m not a burglar; I’m doing this for a friend of yours—Mr. Benn.”

“What?” said an amazed voice.

“True as I stand here,” asseverated Mr. Travers. “Here, here’s my instructions. I’ll put ‘em under the door, and if you go to the back window you’ll see him in the garden waiting.”

He rustled the paper under the door, and it was at once snatched from his fingers. He regained an upright position and stood listening to the startled and indignant exclamations of his gaoler as she read the boatswain’s permit:

“This is to give notice that I, George Benn, being of sound mind and body, have told Ned Travers to pretend to be a burglar at Mrs. Waters’s. He ain’t a burglar, and I shall be outside all the time. It’s all above-board and ship-shape.

“(Signed) George Benn”

“Sound mind—above-board—ship-shape,” repeated a dazed voice. “Where is he?”

“Out at the back,” replied Mr. Travers. “If you go to the window you can see him. Now, do put something round your shoulders, there’s a good girl.”

There was no reply, but a board creaked. He waited for what seemed a long time, and then the board creaked again.

“Did you see him?” he inquired.

“I did,” was the sharp reply. “You both ought to be ashamed of yourselves. You ought to be punished.”

“There is a clothes-peg sticking into the back of my head,” remarked Mr. Travers. “What are you going to do?”

There was no reply.

“What are you going to do?” repeated Mr. Travers, somewhat uneasily. “You look too nice to do anything hard; leastways, so far as I can judge through this crack.”

There was a smothered exclamation, and then sounds of somebody moving hastily about the room and the swish of clothing hastily donned.

“You ought to have done it before,” commented the thoughtful Mr. Travers. “It’s enough to give you your death of cold.”

“Mind your business,” said the voice, sharply. “Now, if I let you out, will you promise to do exactly as I tell you?”

“Honour bright,” said Mr. Travers, fervently.

“I’m going to give Mr. Benn a lesson he won’t forget,” proceeded the other, grimly. “I’m going to fire off this gun, and then run down and tell him I’ve killed you.”

“Eh?” said the amazed Mr. Travers. “Oh, Lord!”

“H’sh! Stop that laughing,” commanded the voice. “He’ll hear you. Be quiet!”

The key turned in the lock, and Mr. Travers, stepping forth, clapped his hand over his mouth and endeavoured to obey. Mrs. Waters, stepping back with the gun ready, scrutinized him closely.

“Come on to the landing,” said Mr. Travers, eagerly. “We don’t want anybody else to hear. Fire into this.”

He snatched a patchwork rug from the floor and stuck it up against the balusters. “You stay here,” said Mrs. Waters. He nodded.

She pointed the gun at the hearth-rug, the walls shook with the explosion, and, with a shriek that set Mr. Travers’s teeth on edge, she rushed downstairs and, drawing back the bolts of the back door, tottered outside and into the arms of the agitated boatswain.

“Oh! oh! oh!” she cried.

“What—what’s the matter?” gasped the boatswain.

The widow struggled in his arms. “A burglar,” she said, in a tense whisper. “But it’s all right; I’ve killed him.”

“Kill—” stuttered the other. “Kill——Killed him?”

Mrs. Waters nodded and released herself, “First shot,” she said, with a satisfied air.

The boatswain wrung his hands. “Good heavens!” he said, moving slowly towards the door. “Poor fellow!”

“Come back,” said the widow, tugging at his coat.

“I was—was going to see—whether I could do anything for ‘im,” quavered the boatswain. “Poor fellow!”

“You stay where you are,” commanded Mrs. Waters. “I don’t want any witnesses. I don’t want this house to have a bad name. I’m going to keep it quiet.”

“Quiet?” said the shaking boatswain. “How?”

“First thing to do,” said the widow, thoughtfully, “is to get rid of the body. I’ll bury him in the garden, I think. There’s a very good bit of ground behind those potatoes. You’ll find the spade in the tool-house.”

The horrified Mr. Benn stood stock-still regarding her.

“While you’re digging the grave,” continued Mrs. ‘Waters, calmly, “I’ll go in and clean up the mess.”

The boatswain reeled and then fumbled with trembling fingers at his collar.

Like a man in a dream he stood watching as she ran to the tool-house and returned with a spade and pick; like a man in a dream he followed her on to the garden.

“Be careful,” she said, sharply; “you’re treading down my potatoes.”

The boatswain stopped dead and stared at her. Apparently unconscious of his gaze, she began to pace out the measurements and then, placing the tools in his hands, urged him to lose no time.

“I’ll bring him down when you’re gone,” she said, looking towards the house.

The boatswain wiped his damp brow with the back of his hand. “How are you going to get it downstairs?” he breathed.

“Drag it,” said Mrs. Waters, briefly.

“Suppose he isn’t dead?” said the boat-swain, with a gleam of hope.

“Fiddlesticks!” said Mrs. Waters. “Do you think I don’t know? Now, don’t waste time talking; and mind you dig it deep. I’ll put a few cabbages on top afterwards—I’ve got more than I want.”

She re-entered the house and ran lightly upstairs. The candle was still alight and the gun was leaning against the bed-post; but the visitor had disappeared. Conscious of an odd feeling of disappointment, she looked round the empty room.

“Come and look at him,” entreated a voice, and she turned and beheld the amused countenance of her late prisoner at the door.

“I’ve been watching from the back window,” he said, nodding. “You’re a wonder; that’s what you are. Come and look at him.”

Mrs. Waters followed, and leaning out of the window watched with simple pleasure the efforts of the amateur sexton. Mr. Benn was digging like one possessed, only pausing at intervals to straighten his back and to cast a fearsome glance around him. The only thing that marred her pleasure was the behaviour of Mr. Travers, who was struggling for a place with all the fervour of a citizen at the Lord Mayor’s show.

“Get back,” she said, in a fierce whisper. “He’ll see you.”

Mr. Travers with obvious reluctance obeyed, just as the victim looked up.

“Is that you, Mrs. Waters?” inquired the boatswain, fearfully.

“Yes, of course it is,” snapped the widow. “Who else should it be, do you think? Go on! What are you stopping for?”

Mr. Benn’s breathing as he bent to his task again was distinctly audible. The head of Mr. Travers ranged itself once more alongside the widow’s. For a long time they watched in silence.

“Won’t you come down here, Mrs. Waters?” called the boatswain, looking up so suddenly that Mr. Travers’s head bumped painfully against the side of the window. “It’s a bit creepy, all alone.”

“I’m all right,” said Mrs. Waters.

“I keep fancying there’s something dodging behind them currant bushes,” pursued the unfortunate Mr. Benn, hoarsely. “How you can stay there alone I can’t think. I thought I saw something looking over your shoulder just now. Fancy if it came creeping up behind and caught hold of you! The widow gave a sudden faint scream.

“If you do that again!” she said, turning fiercely on Mr. Travers.

“He put it into my head,” said the culprit, humbly; “I should never have thought of such a thing by myself. I’m one of the quietest and best-behaved——”

“Make haste, Mr. Benn,” said the widow, turning to the window again; “I’ve got a lot to do when you’ve finished.”

The boatswain groaned and fell to digging again, and Mrs. Waters, after watching a little while longer, gave Mr. Travers some pointed instructions about the window and went down to the garden again.

“That will do, I think,” she said, stepping into the hole and regarding it critically. “Now you’d better go straight off home, and, mind, not a word to a soul about this.”

She put her hand on his shoulder, and noticing with pleasure that he shuddered at her touch led the way to the gate. The boat-swain paused for a moment, as though about to speak, and then, apparently thinking better of it, bade her good-bye in a hoarse voice and walked feebly up the road. Mrs. Waters stood watching until his steps died away in the distance, and then, returning to the garden, took up the spade and stood regarding with some dismay the mountainous result of his industry. Mr. Travers, who was standing just inside the back door, joined her.

“Let me,” he said, gallantly.

The day was breaking as he finished his task. The clean, sweet air and the exercise had given him an appetite to which the smell of cooking bacon and hot coffee that proceeded from the house had set a sharper edge. He took his coat from a bush and put it on. Mrs. Waters appeared at the door.

“You had better come in and have some breakfast before you go,” she said, brusquely; “there’s no more sleep for me now.”

Mr. Travers obeyed with alacrity, and after a satisfying wash in the scullery came into the big kitchen with his face shining and took a seat at the table. The cloth was neatly laid, and Mrs. Waters, fresh and cool, with a smile upon her pleasant face, sat behind the tray. She looked at her guest curiously, Mr. Travers’s spirits being somewhat higher than the state of his wardrobe appeared to justify.

“Why don’t you get some settled work?” she inquired, with gentle severity, as he imparted snatches of his history between bites.

“Easier said than done,” said Mr. Travers, serenely. “But don’t you run away with the idea that I’m a beggar, because I’m not. I pay my way, such as it is. And, by-the-bye, I s’pose I haven’t earned that two pounds Benn gave me?”

His face lengthened, and he felt uneasily in his pocket.

“I’ll give them to him when I’m tired of the joke,” said the widow, holding out her hand and watching him closely.

Mr. Travers passed the coins over to her. “Soft hand you’ve got,” he said, musingly. “I don’t wonder Benn was desperate. I dare say I should have done the same in his place.”

Mrs. Waters bit her lip and looked out at the window; Mr. Travers resumed his breakfast.

“There’s only one job that I’m really fit for, now that I’m too old for the Army,” he said, confidentially, as, breakfast finished, he stood at the door ready to depart.

“Playing at burglars?” hazarded Mrs. Waters.

“Landlord of a little country public-house,” said Mr. Travers, simply.

Mrs. Waters fell back and regarded him with open-eyed amazement.

“Good morning,” she said, as soon as she could trust her voice.

“Good-bye,” said Mr. Travers, reluctantly. “I should like to hear how old Benn takes this joke, though.”

Mrs. Waters retreated into the house and stood regarding him. “If you’re passing this way again and like to look in—I’ll tell you,” she said, after a long pause. “Good-bye.”

“I’ll look in in a week’s time,” said Mr. Travers.

He took the proffered hand and shook it warmly. “It would be the best joke of all,” he said, turning away.

“What would?”

The soldier confronted her again.

“For old Benn to come round here one evening and find me landlord. Think it over.”

Mrs. Waters met his gaze soberly. “I’ll think it over when you have gone,” she said, softly. “Now go.”

THE NEST EGG

Artfulness,” said the night-watch-man, smoking placidly, “is a gift; but it don’t pay always. I’ve met some artful ones in my time—plenty of ‘em; but I can’t truthfully say as ‘ow any of them was the better for meeting me.”

He rose slowly from the packing-case on which he had been sitting and, stamping down the point of a rusty nail with his heel, resumed his seat, remarking that he had endured it for some time under the impression that it was only a splinter.

“I’ve surprised more than one in my time,” he continued, slowly. “When I met one of these ‘ere artful ones I used fust of all to pretend to be more stupid than wot I really am.”

He stopped and stared fixedly.

“More stupid than I looked,” he said. He stopped again.

“More stupid than wot they thought I looked,” he said, speaking with marked deliberation. And I’d let ‘em go on and on until I thought I had ‘ad about enough, and then turn round on ‘em. Nobody ever got the better o’ me except my wife, and that was only before we was married. Two nights arterwards she found a fish-hook in my trouser-pocket, and arter that I could ha’ left untold gold there—if I’d ha’ had it. It spoilt wot some people call the honey-moon, but it paid in the long run.

One o’ the worst things a man can do is to take up artfulness all of a sudden. I never knew it to answer yet, and I can tell you of a case that’ll prove my words true.

It’s some years ago now, and the chap it ‘appened to was a young man, a shipmate o’ mine, named Charlie Tagg. Very steady young chap he was, too steady for most of ‘em. That’s ‘ow it was me and ‘im got to be such pals.

He’d been saving up for years to get married, and all the advice we could give ‘im didn’t ‘ave any effect. He saved up nearly every penny of ‘is money and gave it to his gal to keep for ‘im, and the time I’m speaking of she’d got seventy-two pounds of ‘is and seventeen-and-six of ‘er own to set up house-keeping with.

Then a thing happened that I’ve known to ‘appen to sailormen afore. At Sydney ‘e got silly on another gal, and started walking out with her, and afore he knew wot he was about he’d promised to marry ‘er too.

Sydney and London being a long way from each other was in ‘is favour, but the thing that troubled ‘im was ‘ow to get that seventy-two pounds out of Emma Cook, ‘is London gal, so as he could marry the other with it. It worried ‘im all the way home, and by the time we got into the London river ‘is head was all in a maze with it. Emma Cook ‘ad got it all saved up in the bank, to take a little shop with when they got spliced, and ‘ow to get it he could not think.

He went straight off to Poplar, where she lived, as soon as the ship was berthed. He walked all the way so as to ‘ave more time for thinking, but wot with bumping into two old gentlemen with bad tempers, and being nearly run over by a cabman with a white ‘orse and red whiskers, he got to the house without ‘aving thought of anything.

They was just finishing their tea as ‘e got there, and they all seemed so pleased to see ‘im that it made it worse than ever for ‘im. Mrs. Cook, who ‘ad pretty near finished, gave ‘im her own cup to drink out of, and said that she ‘ad dreamt of ‘im the night afore last, and old Cook said that he ‘ad got so good-looking ‘e shouldn’t ‘ave known him.

“I should ‘ave passed ‘im in the street,” he ses. “I never see such an alteration.”

“They’ll be a nice-looking couple,” ses his wife, looking at a young chap, named George Smith, that ‘ad been sitting next to Emma.

Charlie Tagg filled ‘is mouth with bread and butter, and wondered ‘ow he was to begin. He squeezed Emma’s ‘and just for the sake of keeping up appearances, and all the time ‘e was thinking of the other gal waiting for ‘im thousands o’ miles away.

“You’ve come ‘ome just in the nick o’ time,” ses old Cook; “if you’d done it o’ purpose you couldn’t ‘ave arranged it better.”

“Somebody’s birthday?” ses Charlie, trying to smile.

Old Cook shook his ‘ead. “Though mine is next Wednesday,” he ses, “and thank you for thinking of it. No; you’re just in time for the biggest bargain in the chandlery line that anybody ever ‘ad a chance of. If you ‘adn’t ha’ come back we should have ‘ad to ha’ done it without you.”

“Eighty pounds,” ses Mrs. Cook, smiling at Charlie. “With the money Emma’s got saved and your wages this trip you’ll ‘ave plenty. You must come round arter tea and ‘ave a look at it.”

“Little place not arf a mile from ‘ere,” ses old Cook. “Properly worked up, the way Emma’ll do it, it’ll be a little fortune. I wish I’d had a chance like it in my young time.”

He sat shaking his ‘ead to think wot he’d lost, and Charlie Tagg sat staring at ‘im and wondering wot he was to do.

“My idea is for Charlie to go for a few more v’y’ges arter they’re married while Emma works up the business,” ses Mrs. Cook; “she’ll be all right with young Bill and Sarah Ann to ‘elp her and keep ‘er company while he’s away.”

“We’ll see as she ain’t lonely,” ses George Smith, turning to Charlie.

Charlie Tagg gave a bit of a cough and said it wanted considering. He said it was no good doing things in a ‘urry and then repenting of ‘em all the rest of your life. And ‘e said he’d been given to understand that chandlery wasn’t wot it ‘ad been, and some of the cleverest people ‘e knew thought that it would be worse before it was better. By the time he’d finished they was all looking at ‘im as though they couldn’t believe their ears.

“You just step round and ‘ave a look at the place,” ses old Cook; “if that don’t make you alter your tune, call me a sinner.”

Charlie Tagg felt as though ‘e could ha’ called ‘im a lot o’ worse things than that, but he took up ‘is hat and Mrs. Cook and Emma got their bonnets on and they went round.

“I don’t think much of it for eighty pounds,” ses Charlie, beginning his artfulness as they came near a big shop, with plate-glass and a double front.

“Eh?” ses old Cook, staring at ‘im. “Why, that ain’t the place. Why, you wouldn’t get that for eight ‘undred.”

“Well, I don’t think much of it,” ses Charlie; “if it’s worse than that I can’t look at it—I can’t, indeed.”

“You ain’t been drinking, Charlie?” ses old Cook, in a puzzled voice.

“Certainly not,” ses Charlie.

He was pleased to see ‘ow anxious they all looked, and when they did come to the shop ‘e set up a laugh that old Cook said chilled the marrer in ‘is bones. He stood looking in a ‘elpless sort o’ way at his wife and Emma, and then at last he ses, “There it is; and a fair bargain at the price.”

“I s’pose you ain’t been drinking?” ses Charlie.

“Wot’s the matter with it?” ses Mrs. Cook flaring up.

“Come inside and look at it,” ses Emma, taking ‘old of his arm.

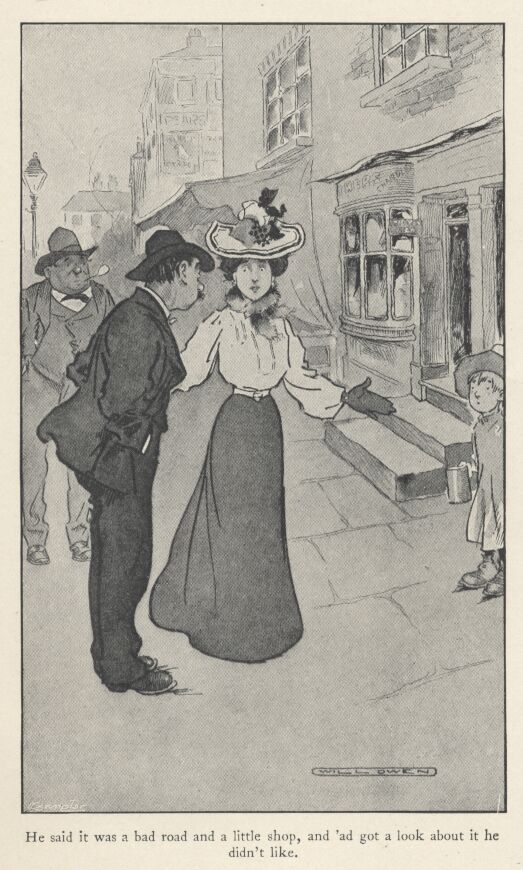

“Not me,” ses Charlie, hanging back. “Why, I wouldn’t take it at a gift.”

He stood there on the kerbstone, and all they could do ‘e wouldn’t budge. He said it was a bad road and a little shop, and ‘ad got a look about it he didn’t like. They walked back ‘ome like a funeral procession, and Emma ‘ad to keep saying “H’s!” in w’ispers to ‘er mother all the way.

“I don’t know wot Charlie does want, I’m sure,” ses Mrs. Cook, taking off ‘er bonnet as soon as she got indoors and pitching it on the chair he was just going to set down on.

“It’s so awk’ard,” ses old Cook, rubbing his ‘cad. “Fact is, Charlie, we pretty near gave ‘em to understand as we’d buy it.”

“It’s as good as settled,” ses Mrs. Cook, trembling all over with temper.

“They won’t settle till they get the money,” ses Charlie. “You may make your mind easy about that.”

“Emma’s drawn it all out of the bank ready,” ses old Cook, eager like.

Charlie felt ‘ot and cold all over. “I’d better take care of it,” he ses, in a trembling voice. “You might be robbed.”

“So might you be,” ses Mrs. Cook. “Don’t you worry; it’s in a safe place.”

“Sailormen are always being robbed,” ses George Smith, who ‘ad been helping young Bill with ‘is sums while they ‘ad gone to look at the shop. “There’s more sailormen robbed than all the rest put together.”

“They won’t rob Charlie,” ses Mrs. Cook, pressing ‘er lips together. “I’ll take care o’ that.”

Charlie tried to laugh, but ‘e made such a queer noise that young Bill made a large blot on ‘is exercise-book, and old Cook, wot was lighting his pipe, burnt ‘is fingers through not looking wot ‘e was doing.

“You see,” ses Charlie, “if I was robbed, which ain’t at all likely, it ‘ud only be me losing my own money; but if you was robbed of it you’d never forgive yourselves.”

“I dessay I should get over it,” ses Mrs. Cook, sniffing. “I’d ‘ave a try, at all events.”

Charlie started to laugh agin, and old Cook, who had struck another match, blew it out and waited till he’d finished.

“The whole truth is,” ses Charlie, looking round, “I’ve got something better to do with the money. I’ve got a chance offered me that’ll make me able to double it afore you know where you are.”

“Not afore I know where I am,” ses Mrs. Cook, with a laugh that was worse than Charlie’s.

“The chance of a lifetime,” ses Charlie, trying to keep ‘is temper. “I can’t tell you wot it is, because I’ve promised to keep it secret for a time. You’ll be surprised when I do tell you.”

“If I wait till then till I’m surprised,” ses Mrs. Cook, “I shall ‘ave to wait a long time. My advice to you is to take that shop and ha’ done with it.”

Charlie sat there arguing all the evening, but it was no good, and the idea o’ them people sitting there and refusing to let ‘im have his own money pretty near sent ‘im crazy. It was all ‘e could do to kiss Emma good-night, and ‘e couldn’t have ‘elped slamming the front door if he’d been paid for it. The only comfort he ‘ad got left was the Sydney gal’s photygraph, and he took that out and looked at it under nearly every lamp-post he passed.

He went round the next night and ‘ad an-other try to get ‘is money, but it was no use; and all the good he done was to make Mrs. Cook in such a temper that she ‘ad to go to bed before he ‘ad arf finished. It was no good talking to old Cook and Emma, because they daren’t do anything without ‘er, and it was no good calling things up the stairs to her because she didn’t answer. Three nights running Mrs. Cook went off to bed afore eight o’clock, for fear she should say something to ‘im as she’d be sorry for arterwards; and for three nights Charlie made ‘imself so disagreeable that Emma told ‘im plain the sooner ‘e went back to sea agin the better she should like it. The only one who seemed to enjoy it was George Smith, and ‘e used to bring bits out o’ newspapers and read to ‘em, showing ‘ow silly people was done out of their money.

On the fourth night Charlie dropped it and made ‘imself so amiable that Mrs. Cook stayed up and made ‘im a Welsh rare-bit for ‘is supper, and made ‘im drink two glasses o’ beer instead o’ one, while old Cook sat and drank three glasses o’ water just out of temper, and to show that ‘e didn’t mind. When she started on the chandler’s shop agin Charlie said he’d think it over, and when ‘e went away Mrs. Cook called ‘im her sailor-boy and wished ‘im pleasant dreams.

But Charlie Tagg ‘ad got better things to do than to dream, and ‘e sat up in bed arf the night thinking out a new plan he’d thought of to get that money. When ‘e did fall asleep at last ‘e dreamt of taking a little farm in Australia and riding about on ‘orseback with the Sydney gal watching his men at work.

In the morning he went and hunted up a shipmate of ‘is, a young feller named Jack Bates. Jack was one o’ these ‘ere chaps, nobody’s enemy but their own, as the saying is; a good-’arted, free-’anded chap as you could wish to see. Everybody liked ‘im, and the ship’s cat loved ‘im. He’d ha’ sold the shirt off ‘is back to oblige a pal, and three times in one week he got ‘is face scratched for trying to prevent ‘usbands knocking their wives about.

Charlie Tagg went to ‘im because he was the only man ‘e could trust, and for over arf an hour he was telling Jack Bates all ‘is troubles, and at last, as a great favour, he let ‘im see the Sydney gal’s photygraph, and told him that all that pore gal’s future ‘appiness depended upon ‘im.

“I’ll step round to-night and rob ‘em of that seventy-two pounds,” ses Jack; “it’s your money, and you’ve a right to it.”

Charlie shook his ‘ead. “That wouldn’t do,” he ses; “besides, I don’t know where they keep it. No; I’ve got a better plan than that. Come round to the Crooked Billet, so as we can talk it over in peace and quiet.”

He stood Jack three or four arf-pints afore ‘e told ‘im his plan, and Jack was so pleased with it that he wanted to start at once, but Charlie persuaded ‘im to wait.

“And don’t you spare me, mind, out o’ friendship,” ses Charlie, “because the blacker you paint me the better I shall like it.”

“You trust me, mate,” ses Jack Bates; “if I don’t get that seventy-two pounds for you, you may call me a Dutchman. Why, it’s fair robbery, I call it, sticking to your money like that.”

They spent the rest o’ the day together, and when evening came Charlie went off to the Cooks’. Emma ‘ad arf expected they was going to a theayter that night, but Charlie said he wasn’t feeling the thing, and he sat there so quiet and miserable they didn’t know wot to make of ‘im.

“‘Ave you got any trouble on your mind, Charlie,” ses Mrs. Cook, “or is it the tooth-ache?”

“It ain’t the toothache,” ses Charlie.

He sat there pulling a long face and staring at the floor, but all Mrs. Cook and Emma could do ‘e wouldn’t tell them wot was the matter with ‘im. He said ‘e didn’t want to worry other people with ‘is troubles; let everybody bear their own, that was ‘is motto. Even when George Smith offered to go to the theayter with Emma instead of ‘im he didn’t fire up, and, if it ‘adn’t ha’ been for Mrs. Cook, George wouldn’t ha’ been sorry that ‘e spoke.

“Theayters ain’t for me,” ses Charlie, with a groan. “I’m more likely to go to gaol, so far as I can see, than a theayter.”

Mrs. Cook and Emma both screamed and Sarah Ann did ‘er first highstericks, and very well, too, considering that she ‘ad only just turned fifteen.

“Gaol!” ses old Cook, as soon as they ‘ad quieted Sarah Ann with a bowl o’ cold water that young Bill ‘ad the presence o’ mind to go and fetch. “Gaol! What for?”

“You wouldn’t believe if I was to tell you.” ses Charlie, getting up to go, “and besides, I don’t want any of you to think as ‘ow I am worse than wot I am.”

He shook his ‘cad at them sorrowful-like, and afore they could stop ‘im he ‘ad gone. Old Cook shouted arter ‘im, but it was no use, and the others was running into the scullery to fill the bowl agin for Emma.

Mrs. Cook went round to ‘is lodgings next morning, but found that ‘e was out. They began to fancy all sorts o’ things then, but Charlie turned up agin that evening more miserable than ever.

“I went round to see you this morning,” ses Mrs. Cook, “but you wasn’t at ‘ome.”

“I never am, ‘ardly,” ses Charlie. “I can’t be—it ain’t safe.”

“Why not?” ses Mrs. Cook, fidgeting.

“If I was to tell you, you’d lose your good opinion of me,” ses Charlie.

“It wouldn’t be much to lose,” ses Mrs. Cook, firing up.

Charlie didn’t answer ‘er. When he did speak he spoke to the old man, and he was so down-’arted that ‘e gave ‘im the chills a’most, He ‘ardly took any notice of Emma, and, when Mrs. Cook spoke about the shop agin, said that chandlers’ shops was for happy people, not for ‘im.

By the time they sat down to supper they was nearly all as miserable as Charlie ‘imself. From words he let drop they all seemed to ‘ave the idea that the police was arter ‘im, and Mrs. Cook was just asking ‘im for wot she called the third and last time, but wot was more likely the hundred and third, wot he’d done, when there was a knock at the front door, so loud and so sudden that old Cook and young Bill both cut their mouths at the same time.

“Anybody ‘ere o’ the name of Emma Cook?” ses a man’s voice, when young Bill opened the door.

“She’s inside,” ses the boy, and the next moment Jack Bates followed ‘im into the room, and then fell back with a start as ‘e saw Charlie Tagg.

“Ho, ‘ere you are, are you?” he ses, looking at ‘im very black. “Wot’s the matter?” ses Mrs. Cook, very sharp.

“I didn’t expect to ‘ave the pleasure o’ seeing you ‘ere, my lad,” ses Jack, still staring at Charlie, and twisting ‘is face up into awful scowls. “Which is Emma Cook?”

“Miss Cook is my name,” ses Emma, very sharp. “Wot d’ye want?”

“Very good,” ses Jack Bates, looking at Charlie agin; “then p’r’aps you’ll do me the kindness of telling that lie o’ yours agin afore this young lady.”

“It’s the truth,” ses Charlie, looking down at ‘is plate.

“If somebody don’t tell me wot all this is about in two minutes, I shall do something desprit,” ses Mrs. Cook, getting up.

“This ‘ere—er—man,” ses Jack Bates, pointing at Charlie, “owes me seventy-five pounds and won’t pay. When I ask ‘im for it he ses a party he’s keeping company with, by the name of Emma Cook, ‘as got it, and he can’t get it.”

“So she has,” ses Charlie, without looking up.

“Wot does ‘e owe you the money for?” ses Mrs. Cook.

“‘Cos I lent it to ‘im,” ses Jack.

“Lent it? What for?” ses Mrs. Cook.

“‘Cos I was a fool, I s’pose,” ses jack Bates; “a good-natured fool. Anyway, I’m sick and tired of asking for it, and if I don’t get it to-night I’m going to see the police about it.”

He sat down on a chair with ‘is hat cocked over one eye, and they all sat staring at ‘im as though they didn’t know wot to say next.

“So this is wot you meant when you said you’d got the chance of a lifetime, is it?” ses Mrs. Cook to Charlie. “This is wot you wanted it for, is it? Wot did you borrow all that money for?”

“Spend,” ses Charlie, in a sulky voice.

“Spend!” ses Mrs. Cook, with a scream; “wot in?”

“Drink and cards mostly,” ses Jack Bates, remembering wot Charlie ‘ad told ‘im about blackening ‘is character.

You might ha’ heard a pin drop a’most, and Charlie sat there without saying a word.

“Charlie’s been led away,” ses Mrs. Cook, looking ‘ard at Jack Bates. “I s’pose you lent ‘im the money to win it back from ‘im at cards, didn’t you?”

“And gave ‘im too much licker fust,” ses old Cook. “I’ve ‘eard of your kind. If Charlie takes my advice ‘e won’t pay you a farthing. I should let you do your worst if I was ‘im; that’s wot I should do. You’ve got a low face; a nasty, ugly, low face.”

“One o’ the worst I ever see,” ses Mrs. Cook. “It looks as though it might ha’ been cut out o’ the Police News.”

“‘Owever could you ha’ trusted a man with a face like that, Charlie?” ses old Cook. “Come away from ‘im, Bill; I don’t like such a chap in the room.”

Jack Bates began to feel very awk’ard. They was all glaring at ‘im as though they could eat ‘im, and he wasn’t used to such treatment. And, as a matter o’ fact, he’d got a very good-’arted face.

“You go out o’ that door,” ses old Cook, pointing to it. “Go and do your worst. You won’t get any money ‘ere.”

“Stop a minute,” ses Emma, and afore they could stop ‘er she ran upstairs. Mrs. Cook went arter ‘er and ‘igh words was heard up in the bedroom, but by-and-by Emma came down holding her head very ‘igh and looking at Jack Bates as though he was dirt.

“How am I to know Charlie owes you this money?” she ses.

Jack Bates turned very red, and arter fumbling in ‘is pockets took out about a dozen dirty bits o’ paper, which Charlie ‘ad given ‘im for I O U’s. Emma read ‘em all, and then she threw a little parcel on the table.

“There’s your money,” she ses; “take it and go.”

Mrs. Cook and ‘er father began to call out, but it was no good.

“There’s seventy-two pounds there,” ses Emma, who was very pale; “and ‘ere’s a ring you can have to ‘elp make up the rest.” And she drew Charlie’s ring off and throwed it on the table. “I’ve done with ‘im for good,” she ses, with a look at ‘er mother.

Jack Bates took up the money and the ring and stood there looking at ‘er and trying to think wot to say. He’d always been uncommon partial to the sex, and it did seem ‘ard to stand there and take all that on account of Charlie Tagg.

“I only wanted my own,” he ses, at last, shuffling about the floor.

“Well, you’ve got it,” ses Mrs. Cook, “and now you can go.”

“You’re pi’soning the air of my front parlour,” ses old Cook, opening the winder a little at the top.

“P’r’aps I ain’t so bad as you think I am,” ses Jack Bates, still looking at Emma, and with that ‘e walked over to Charlie and dumped down the money on the table in front of ‘im. “Take it,” he ses, “and don’t borrow any more. I make you a free gift of it. P’r’aps my ‘art ain’t as black as my face,” he ses, turning to Mrs. Cook.

They was all so surprised at fust that they couldn’t speak, but old Cook smiled at ‘im and put the winder up agin. And Charlie Tagg sat there arf mad with temper, locking as though ‘e could eat Jack Bates without any salt, as the saying is.

“I—I can’t take it,” he ses at last, with a stammer.

“Can’t take it? Why not?” ses old Cook, staring. “This gentleman ‘as given it to you.” “A free gift,” ses Mrs. Cook, smiling at Jack very sweet.

“I can’t take it,” ses Charlie, winking at Jack to take the money up and give it to ‘im quiet, as arranged. “I ‘ave my pride.”

“So ‘ave I,” ses Jack. “Are you going to take it?”

Charlie gave another look. “No,” he ses, “I cant take a favour. I borrowed the money and I’ll pay it back.

“Very good,” ses Jack, taking it up. “It’s my money, ain’t it?”

“Yes,” ses Charlie, taking no notice of Mrs. Cook and ‘er husband, wot was both talking to ‘im at once, and trying to persuade ‘im to alter his mind.

“Then I give it to Miss Emma Cook,” ses Jack Bates, putting it into her hands. “Good-night everybody and good luck.”

He slammed the front door behind ‘im and they ‘eard ‘im go off down the road as if ‘e was going for fire-engines. Charlie sat there for a moment struck all of a heap, and then ‘e jumped up and dashed arter ‘im. He just saw ‘im disappearing round a corner, and he didn’t see ‘im agin for a couple o’ year arterwards, by which time the Sydney gal had ‘ad three or four young men arter ‘im, and Emma, who ‘ad changed her name to Smith, was doing one o’ the best businesses in the chandlery line in Poplar.

THE CONSTABLE’S MOVE

Mr. Bob Grummit sat in the kitchen with his corduroy-clad legs stretched on the fender. His wife’s half-eaten dinner was getting cold on the table; Mr. Grummit, who was badly in need of cheering up, emptied her half-empty glass of beer and wiped his lips with the back of his hand.

“Come away, I tell you,” he called. “D’ye hear? Come away. You’ll be locked up if you don’t.”

He gave a little laugh at the sarcasm, and sticking his short pipe in his mouth lurched slowly to the front-room door and scowled at his wife as she lurked at the back of the window watching intently the furniture which was being carried in next door.

“Come away or else you’ll be locked up,” repeated Mr. Grummit. “You mustn’t look at policemen’s furniture; it’s agin the law.”

Mrs. Grummit made no reply, but, throwing appearances to the winds, stepped to the window until her nose touched, as a walnut sideboard with bevelled glass back was tenderly borne inside under the personal supervision of Police-Constable Evans.

“They’ll be ‘aving a pianner next,” said the indignant Mr. Grummit, peering from the depths of the room.

“They’ve got one,” responded his wife; “there’s the end if it stickin’ up in the van.”

Mr. Grummit advanced and regarded the end fixedly. “Did you throw all them tin cans and things into their yard wot I told you to?” he demanded.

“He picked up three of ‘em while I was upstairs,” replied his wife. “I ‘eard ‘im tell her that they’d come in handy for paint and things.”

“That’s ‘ow coppers get on and buy pianners,” said the incensed Mr. Grummit, “sneaking other people’s property. I didn’t tell you to throw good ‘uns over, did I? Wot d’ye mean by it?”

Mrs. Grummit made no reply, but watched with bated breath the triumphal entrance of the piano. The carman set it tenderly on the narrow footpath, while P. C. Evans, stooping low, examined it at all points, and Mrs. Evans, raising the lid, struck a few careless chords.

“Showing off,” explained Mrs. Grummit, with a half turn; “and she’s got fingers like carrots.”

“It’s a disgrace to Mulberry Gardens to ‘ave a copper come and live in it,” said the indignant Grummit; “and to come and live next to me!— that’s what I can’t get over. To come and live next door to a man wot has been fined twice, and both times wrong. Why, for two pins I’d go in and smash ‘is pianner first and ‘im after it. He won’t live ‘ere long, you take my word for it.”

“Why not?” inquired his wife.

“Why?” repeated Mr. Grummit. “Why? Why, becos I’ll make the place too ‘ot to hold him. Ain’t there enough houses in Tunwich without ‘im a-coming and living next door to me?”

For a whole week the brain concealed in Mr. Grummit’s bullet-shaped head worked in vain, and his temper got correspondingly bad. The day after the Evans’ arrival he had found his yard littered with tins which he recognized as old acquaintances, and since that time they had travelled backwards and forwards with monotonous regularity. They sometimes made as many as three journeys a day, and on one occasion the heavens opened to drop a battered tin bucket on the back of Mr. Grummit as he was tying his bootlace. Five minutes later he spoke of the outrage to Mr. Evans, who had come out to admire the sunset.

“I heard something fall,” said the constable, eyeing the pail curiously.

“You threw it,” said Mr. Grummit, breathing furiously.

“Me? Nonsense,” said the other, easily. “I was having tea in the parlour with my wife and my mother-in-law, and my brother Joe and his young lady.”

“Any more of ‘em?” demanded the hapless Mr. Grummit, aghast at this list of witnesses for an alibi.

“It ain’t a bad pail, if you look at it properly,” said the constable. “I should keep it if I was you; unless the owner offers a reward for it. It’ll hold enough water for your wants.”

Mr. Grummit flung indoors and, after wasting some time concocting impossible measures of retaliation with his sympathetic partner, went off to discuss affairs with his intimates at the Bricklayers’ Arms. The company, although unanimously agreeing that Mr. Evans ought to be boiled, were miserably deficient in ideas as to the means by which such a desirable end was to be attained.

“Make ‘im a laughing-stock, that’s the best thing,” said an elderly labourer. “The police don’t like being laughed at.”

“‘Ow?” demanded Mr. Grummit, with some asperity.

“There’s plenty o’ ways,” said the old man.

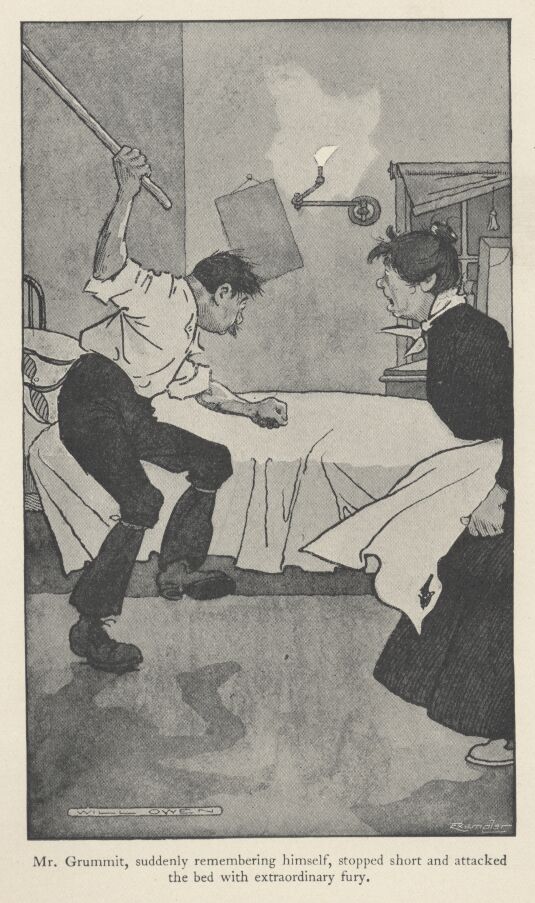

“I should find ‘em out fast enough if I ‘ad a bucket dropped on my back, I know.”