Reproduced From A Photograph On Porcelain

In The Possession Of Mrs Loewe Taken At The Age Of 80

Reproduced From A Photograph On Porcelain

In The Possession Of Mrs Loewe Taken At The Age Of 80

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Diaries of Sir Moses and Lady Montefiore,

Volume I, by Sir Moses Montefiore and Judith Montefiore

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Diaries of Sir Moses and Lady Montefiore, Volume I

Comprising Their Life and Work as Recorded in Their Diaries

From 1812 to 1883

Author: Sir Moses Montefiore

Judith Montefiore

Editor: Dr. L. Loewe

Release Date: August 2, 2008 [EBook #26170]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIR MOSES, LADY MONTEFIORE, VOL. I ***

Produced by David Starner, Roberta Staehlin and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file made from images generously made available by Seforim

Online.)

Reproduced From A Photograph On Porcelain

In The Possession Of Mrs Loewe Taken At The Age Of 80

Reproduced From A Photograph On Porcelain

In The Possession Of Mrs Loewe Taken At The Age Of 80

HELIOG LEMERCIER Et Cie PARIS

DIARIES OF

SIR MOSES

AND LADY MONTEFIORE

COMPRISING THEIR LIFE AND WORK AS RECORDED

IN THEIR DIARIES FROM 1812 TO 1883.

WITH THE ADDRESSES AND SPEECHES OF SIR MOSES; HIS CORRESPONDENCE WITH

MINISTERS, AMBASSADORS, AND REPRESENTATIVES OF PUBLIC BODIES;

PERSONAL NARRATIVES OF HIS MISSIONS IN THE CAUSE OF HUMANITY;

FIRMANS AND EDICTS OF EASTERN MONARCHS; HIS OPINIONS ON

FINANCIAL, POLITICAL, AND RELIGIOUS SUBJECTS, AND

ANECDOTES AND INCIDENTS REFERRING TO MEN

OF HIS TIME, AS RELATED BY HIMSELF.

EDITED BY

DR L. LOEWE,

MEMBER OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY OF GREAT BRITAIN AND IRELAND OF THE SOCIETE

ASIATIQUE OF PARIS OF THE NUMISMATIC SOCIETY OF LONDON, ETC (ONE OF THE

MEMBERS OF THE MISSION TO DAMASCUS AND CONSTANTINOPLE UNDER

THE LATE SIR MOSES MONTEFIORE BART, IN THE YEAR 1840).

ASSISTED BY HIS SON.

In Two Volumes

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

VOL. I.

CHICAGO:

BELFORD-CLARKE CO.

1890.

Ancient Coat Of Arms Of The Montefiore Family,

explained on page 6.

Ancient Coat Of Arms Of The Montefiore Family,

explained on page 6.

(The rights of translation and of reproduction are reserved.)

Copyright—Belford-Clarke Co., Chicago.

In submitting to the public the Memoirs, including the Diaries, of Sir Moses and Lady Montefiore, I deem it desirable to explain the motives by which I have been actuated, as well as the sources from which most of my information has been drawn.

The late Sir Moses Montefiore, from a desire to show his high appreciation of the services rendered to the cause of humanity by Judith, Lady Montefiore, his affectionate partner in life, directed the executors of his last will "to permit me to take into my custody and care all the notes, memoranda, journals, and manuscripts in his possession written by his deeply lamented wife, to assist me in writing a Memoir of her useful and blessed life."

The executors having promptly complied with these instructions, I soon found myself in possession of five journals by Lady Montefiore, besides many valuable letters and papers, including documents of great importance, as well as of no less than eighty-five diaries of Sir Moses Montefiore, dating from 1814 to 1883, all in his own handwriting.

In addition to such facilities for producing a Memoir, I had the special advantage of personally knowing both Sir Moses and Lady Montefiore for many years. There is an entry in the diaries referring to a dinner at the house of one of their relatives on the 27th of November 1835 (where I met them for the first time), and to a visit I subsequently paid them at East Cliff Lodge, Ramsgate, by special invitation, from the 3rd to the 13th of December of the same year.

I also had the privilege of accompanying them on thirteen philanthropic missions to foreign lands, some of which were undertaken by both Sir Moses and Lady Montefiore, and others by Sir Moses alone after Lady Montefiore's death. The first of these missions took place in the year 1839, and the last in 1874.

A no less important circumstance, which I may perhaps be allowed to mention, is, that I was with Sir Moses on the last day of his life, until he breathed his last, and had the satisfaction of hearing from his own lips, immediately before his death, the expression of his approval of my humble endeavours to assist him, as far as lay in my power, in attaining the various objects he had in view.

However desirous I might have been to adhere strictly to his wishes, I found it impossible to write a Memoir of Lady Montefiore without making it, at the same time, a Memoir of Sir Moses himself, both of them having been so closely united in all their benevolent works and projects. It appeared to me most desirable, therefore, in order to convey to the reader a correct idea of the contents of the book, to entitle it "The Diaries of Sir Moses and Lady Montefiore."

In order, however, to comply with the instructions of the will, I shall, in giving the particulars of their family descent, first introduce the parentage of Lady Montefiore.

To assist the reader in finding the exact month and year referring to Hebrew Communal affairs, I have always given the Hebrew date conjointly with that of the Christian era, more especially as all the entries in the diaries invariably have these double dates.

L. LOEWE.

1Oscar Villas, Broadstairs, Kent,

21st June 1887 (5647 a.m.).

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Birth of Sir Moses Montefiore at Leghorn—His Family—Early Years | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Early Education—Becomes a Stockbroker—His Marriage | 12 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Extracts from the Diaries—Financial Transactions—Public Events before and after and after Waterloo—Elected President of the Spanish and Portuguese Hebrew Community | 19 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Daily Life—Death of his Brother Abraham—An early Panama Canal Project | 25 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| First Journey to Jerusalem | 36 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Mr and Mrs Montefiore leave Alexandria—A Sea Voyage Sixty Years ago | 47 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Arrival in England—Illness of Mr Montefiore—The Struggle for Jewish Emancipation | 55 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Lady Hester Stanhope—Her Eccentricities—Parliament and the Jews | 63 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Mr Montefiore presented to the King—Spanish and Portuguese Jews in London in 1829 | 69 |

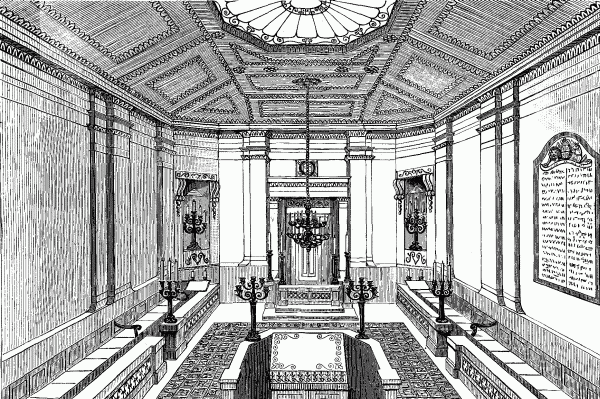

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Interview with the Duke of Wellington in furtherance of the Jewish—Cause—The Duke's Dilatory Tactics—Laying the Foundation-stone of the Synagogue at Hereson | 78 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Lord Brougham and the Jews—The Jewish Poor in London—Mr Montefiore hands his Broker's Medal to his Brother—Dedication of the Synagogue at Hereson—The Lords reject the Jewish Disabilities Bill | 86 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Illness of Mr Montefiore—His Recovery—Sir David Salomons proposed as Sheriff—Visit of the Duchess of Kent and Princess Victoria to Ramsgate—Mr Montefiore's Hospitals—Naming of the Vessel Britannia by Mrs Montefiore—A Loan of Fifteen Millions | 93 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Death of Mr N. M. Rothschild—Mr Montefiore visits Dublin—Becomes the First Jewish Member of the Royal Society—Death of William IV.—Mr Montefiore elected Sheriff | 103 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| The Jews' Marriage Bill—Mr Montefiore at the Queen's Drawing-Room—His Inauguration as Sheriff | 111 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Death of Mr Montefiore's Uncle—Mr Montefiore rides in the Lord Mayor's Procession—Is Knighted—His Speech at the Lord Mayor's Banquet—Presents Petition on behalf of the Jews to Parliament | 119 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Destruction of the Royal Exchange—City Traditions—"Jews' Walk"—Sir Moses dines at Lambeth Palace | 130 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Another Petition to Parliament—Sir Moses intercedes successfully for the Life of a Convict—Death of Lady Montefiore's Brother | 137 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Bartholomew Fair—Sir Moses earns the Thanks of the City—Preparations for a Second Journey to the Holy Land—The Journey—Adventures on Road and River in France | 145 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Genoa, Carrara, Leghorn, and Rome—Disquieting Rumours—Quarantine Precautions—Arrival at Alexandria—Travel in the Holy Land | 153 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Reception at Safed—Sad Condition of the People—Sir Moses' Project for the Cultivation of the Land in Palestine by the Jews—Death of the Chief Rabbi of the German Congregation in Jerusalem—Tiberias | 162 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Invitation from the Portuguese Congregation at Jerusalem—Sanitary Measures in the Holy City—The Wives of the Governor of Tiberias visit Lady Montefiore—A Pleasant Journey—Arrival at Jerusalem | 171 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| The Tomb of David—Spread of the Plague—Mussulman Fanaticism—Suspicious Conduct of the Governor of Jerusalem—Nayani, Beth Dagon, Jaffa, Emkhalet, and Tantura | 180 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Encampment near Mount Carmel—State of the Country—Child Marriages in the Portuguese Community at Haifa—Arrival in Beyrout | 188 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| On Board the Acheron—Sir Moses' Plans on behalf of the Jews in Palestine—Interview with Boghoz Bey—Proposed Joint Stock Banks in the East | 196 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Arrival at Malta—Home again—Boghoz Bey returns no Answer—Touching Appeal from the Persecuted Jews of Damascus and Rhodes—Revival of the old Calumny about killing Christians to put their Blood in Passover Cakes | 204 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Indignation Meetings in London—M. Crémieux—Lord Palmerston's Action—Sir Moses starts on a Mission to the East—Origin of the Passover Cake Superstition | 213 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Arrival at Leghorn—Alexandria—Sir Moses' Address to the Pasha—Action of the Grand Vizir | 222 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| Authentic Accounts of the Circumstances attending the Accusations against the Jews—Terrible Sufferings of the Accused—Evidence of their Innocence—Witnesses in their favour Bastinadoed to Death | 229 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Affairs in the East—Ultimatum from the Powers—Gloomy Prospects of the Mission—Negotiations with the Pasha—Excitement in Alexandria—Illness of Lady Montefiore | 240 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| The English Government and the Pasha—Mohhammad Ali and the Slaves—The Pasha promises to release the DamascusPrisoners—He grants them an "Honourable Liberation" | 248 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| Interview with the Pasha—Liberation of the Jews of Damascus—Public Rejoicings and Thanksgiving—Departure of Sir Moses for Constantinople | 256 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Constantinople—Condition of the Jewish Residents—Interview with Rechid Pasha—Audience with the Sultan—He grants a Firman | 266 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Distress among the Jews at Salonica—Oppressive Laws with regard to them—Text of the Firman—Its Promulgation | 275 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| Departure from Malta—Naples—Rome—A Shameful Inscription—Prejudices against the Jews at the Vatican | 282 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| Monsignor Bruti and his Hints—Cardinal Riverola—Ineffectual Attempts to Interview the Pope—Returning Homewards—Alarming Accident—The Governor of Genoa—Interview with King Louis Philippe | 289 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| Home again—Sir Moses presents a Facsimile of the Firman to the Queen—Her Majesty's Special Mark of Favour—Reform Movement among the London Jews—Appeal for English Protection from the Jews in the East | 298 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

| Presentation from Hamburg—Sir Moses meets the King of Prussia—Address to Prince Albert—Attempt on the Queen's Life—Petitions to Sir Moses from Russia | 305 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| Address and Testimonial from the Jews—Sir Moses' Speech in reply—Death of the Duke of Sussex—The Deportation Ukase in Russia—Opening of the New Royal Exchange—Sir Moses made Sheriff of Kent | 313 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| Affairs in Morocco—Letter to the Emperor—His Reply—Deputation to Sir Robert Peel—Death of Lady Montefiore's Brother Isaac—Sir Moses sets out for Russia | 320 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| Perils of Russian Travelling in Winter—Arrival at St Petersburg—Interviews with Count Nesselrode and the Czar—Count Kisseleff's Prejudices | 328 |

| CHAPTER XLI. | |

| Count Kisseleff is more Conciliatory—Sir Moses sets out for Wilna—Arrival at Wilna—The Jews' Answers to the Charges of Russian Officials | 336 |

| CHAPTER XLII. | |

| The Jewish Schools at Wilna—Wilcomir—Deplorable Condition of the Hebrew Community in that Town—Kowno—Warsaw | 344 |

| CHAPTER XLIII. | |

| Deputation from Krakau—The Polish Jews and their Garb—Sir Moses leaves Warsaw—Posen, Berlin, and Frankfort—Home | 351 |

| CHAPTER XLIV. | |

| Sir Moses receives the Congratulations of his English Co-religionists—His Exhaustive Report to Count Kisseleff—Examination of the Charges against the Jews—Their Alleged Disinclination to engage in Agriculture | 359 |

| CHAPTER XLV. | |

| Report to Count Ouvaroff on the State of Education among the Jews in Russia and Poland—Vindication of the Loyalty of the Jews | 374 |

| CHAPTER XLVI. | |

| Report to Count Kisseleff on the State of the Jews in Poland—Protest against the Restrictions to which they were subjected | 381 |

| CHAPTER XLVII. | |

| The Czar's Reply to Sir Moses' Representations—Count Ouvaroff's Views—Sir Moses again writes to Count Kisseleff—Sir Moses is created a Baronet | 385 |

The neighbourhood of the Tower of London was, a hundred years ago, the centre of attraction for thousands of persons engaged in financial pursuits, not so much on account of the protection which the presence of the garrison might afford in case of tumult, as of the convenience offered by the locality from its vicinity to the wharves, the Custom House, the Mint, the Bank, the Royal Exchange, and many important counting-houses and places of business. For those who took an interest in Hebrew Communal Institutions, it possessed the additional advantage of being within ten minutes or a quarter of an hour's walk of the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue and the Great German Synagogue, together with their Colleges and Schools, and several minor places of worship.

Tower Hill, the Minories, and the four streets enclosing the Tenter Ground were then favourite places of residence for the merchant; and in one of these, Great Prescott Street, lived Levi Barent Cohen, the father of Judith, afterwards Lady Montefiore.

He was a wealthy merchant from Amsterdam, who settled in England, where fortune favoured his commercial undertakings.

In his own country his name is to this day held in great respect. He not only during his lifetime kept up a cordial correspondence with his friends and relatives—who were indebted to him for many acts of kindness—but, wishing to have[Pg 2] his name commemorated in the House of Prayer by some act of charity, he bequeathed a certain sum of money to be given annually to the poor, in consideration of which, he desired to have some of the Daily Prayers offered up from the very place which he used to occupy in the Synagogue of his native city.

He was a man, upright in all his transactions, and a strict adherent to the tenets of his religion. He was of a very kind and sociable disposition, which prompted him to keep open house for his friends and visitors, whom he always received with the most generous hospitality. He was first married to Fanny, a daughter of Joseph Diamantschleifer of Amsterdam, by whom he had three children: two sons, Solomon and Joseph, and one daughter, Fanny.

Solomon became the father-in-law of the late Sir David Salomons, and Joseph the father of the late Mr Louis Cohen. Fanny married Salomon Hyman Cohen Wessels, of Amsterdam, a gentleman who was well known at that time for his philanthropy, and whose family, at the period of Napoleon I., was held in great esteem among the aristocracy of Holland.

Mrs Levi Barent Cohen unfortunately died at an early age, and Mr Cohen married her sister Lydia, by whom he had seven children: five daughters—Hannah, Judith, Jessy, Adelaide, and Esther; and two sons—Isaac and Benjamin.

Hannah became the wife of Mr N. M. Rothschild; Judith was married to Mr Moses Montefiore; Jessy to Mr Davidson; Adelaide to Mr John Hebbert; and Esther to Mr S. M. Samuel, the father of Mr George Samuel, and grandfather of Baron Henry de Worms, M. P. Isaac became the father-in-law of Baron Meyer de Rothschild, and Benjamin the father of Mr Arthur Cohen, Q. C., and Mr Nath. B. Cohen.

Judith, one of the subjects of these Memoirs, was born, according to the entry in one of Sir Moses' Diaries, on the 20th February 1784; her birthday, however, was generally celebrated at East Cliff Lodge in the month of October, in conjunction with another festivity held there on the first Saturday after the Tabernacle Holidays.

With regard to most persons noted for their character or ability, there exists a tradition of some unusual occurrence happening during their early life. In the case of Lady Montefiore, there is an event which she once related to me herself.[Pg 3]

"When I was a little girl," she said, "about three or four years old, I fell over the railing of a staircase, quite two storeys high, into the hall below. Everybody in the house thought I must be killed, but when they came to pick me up they found me quietly seated as if nothing in the world had happened to me."

It was a characteristic of hers which was subsequently much noticed by those around her, that, no matter in what circumstances she was placed, when others were excited or depressed by some painful event or the fear of approaching peril, she would remain calm, and retain her presence of mind. She would endeavour to cheer and strengthen others by words of hope, and where it was possible to avoid any threatened danger, she would quietly give her opinion as to the best course to be pursued.

She received from her earliest childhood an excellent English education, and her studies in foreign languages were most successful. She spoke French, German, and Italian fluently, and read and translated correctly the Hebrew language of her prayers, as well as portions of the Pentateuch, generally read in the Synagogues on Sabbaths and Festivals.

Nor were the accomplishments of music and drawing neglected; but that which characterised and enhanced the value of her education most was "the fear of God," which, she had been taught, constituted "the beginning of knowledge."

By the example set in her parents' house, this lesson took an especially deep root in her heart. One day at Park Lane the conversation happened to turn on the practice of religious observances, and Lady Montefiore related what had occurred when she was still under the parental roof.

"Once," she said, "on the fast-day for the destruction of Jerusalem, we were sitting, as is customary, in mourning attire, on low stools, reciting the Lamentations of Jeremiah. Suddenly the servant entered the room, closely followed by Admiral Sir Sidney Smith, and several other gentlemen. My sisters became somewhat embarrassed, not liking to be thus surprised in our peculiar position, but I quietly kept my seat, and when Sir Sidney asked the reason of our being seated so low, I replied, This is the anniversary of the destruction of Jerusalem, which is kept by conforming Jews as a day of mourning and humiliation.[Pg 4] The valour exhibited by our ancestors on this sad occasion is no doubt well known to you, Sir Sidney, and to the other gentlemen present, and I feel sure that you will understand our grief that it was unavailing to save the Holy City and the Temple. But we treasure the memory of it as a bright example to ourselves and to all following generations, how to fight and to sacrifice our lives for the land in which we were born and which gives us shelter and protection."

"Sir Sidney and the other gentlemen," she said, "appeared to be much pleased with the explanation I gave them; they observed that it was a most noble feeling which prompts the true patriot to mourn for the brave who have fallen on the field of battle for their country; and that the memory of the struggles of the Jews in Palestine to remain the rightful masters of the land which God had apportioned to them as an inheritance, would ever remain, not only in the heart of every brave man in the British realm, but also in that of every right-thinking man in all other parts of the world as a glorious monument of their dauntless valour and fervent devotion to a good and holy cause."

Lady Montefiore not only appreciated the education she received, but also remembered with deep gratitude all those who had imparted instruction to her. Her friends have often been the bearers of generous pensions to gentlemen who had been her teachers when she was young, and they never heard her mention their names without expressions of gratitude.

In addition to her other good qualities, there was one which is not always to be met with among those who happen to be in possession of great wealth, and with whom a few shillings are not generally an object worth entering in an account-book. With her, when her turn came among her sisters to superintend the management of the house, the smallest item of expense was entered with scrupulous accuracy, and whilst ever generous towards the deserving and needy who applied to her for assistance, she would never sanction the slightest waste.

I shall presently, as I proceed in my description of her character, have an opportunity of showing how, in her future position as a wife and philanthropist, all the excellences of her character were turned to the best account for the benefit of those to whom she and her husband rendered assistance in times of distress.[Pg 5]

The reader being now in full possession of all that is necessary for him to know of the parentage and education of Miss Judith Cohen, I propose to leave her for the present under her parental roof, in Angel Court, Throgmorton Street, with a loving father and a tenderly affectionate mother, and surrounded by excellent brothers and sisters; some of them employed in commercial pursuits, others in study, but all united in the contemplation and practice of works of brotherly love and charity towards their fellow-beings. To proceed with the lineage of Sir Moses.

Sir Moses Montefiore was born at Leghorn, whither his parents happened to repair, either on business or on a visit to their relations, a few weeks before that event took place.

According to an entry in the archives of the Hebrew Community of that city, he first saw the light on the 9th of Héshván 5545 a.m., corresponding to the 24th of October 1784.

During his visit to Leghorn in the year 1841, an opportunity was offered to him, when visiting the schools of the community, to inspect the archives in my presence, and he expressed his satisfaction at their accuracy.

Some doubt having been entertained by several of his biographers of the correctness of the date of his birth, and Sir Moses having generally received and accepted the congratulations of his friends on the the 8th of Héshván, it will not be out of place to give here an exact copy of the original entry in the archives in the Italian language, just as it has recently been forwarded to me by the Cavaliere Costa of Leghorn.

It reads as follows:—

"Nei registri di Nascite che esistone nell' archivìe delle Università Israelitica a C. 8, si trova la seguente nascita:—

"9 Héshván, 5545—24 Ottobre 1784. "Domenica.

"A Joseph di Moise Haim e Raquel Montefiore un figlio, che chiamarone Moise Haim."

(Translation.)

"In the registers of births, which are preserved in the archives of the Hebrew community, there is to be found on p. 8 the following entry of birth:[Pg 6]—

"9th Héshván 5545 a.m., 24th October 1784. "Sunday.

"Unto Joseph, son of Moses Haim, and Rachel Montefiore, a son was born, whom they call Moses Haim."

Sir Moses never signed his name "Haim," nor did his mother in her letters to him ever call him so. His father Joseph, after recovering from a dangerous illness, adopted the name of Eliyáhoo (the Eternal is my God) in addition to that of Joseph.

Various opinions have been expressed respecting the early history of Sir Moses Montefiore's ancestors, and the place whence they originally came, to Modena, Ancona, Fano, Rome, and Leghorn.

A manuscript in the library of "Judith Lady Montefiore's Theological College" at Ramsgate—containing a design of the original armorial bearings of the Montefiore family, surrounded by suitable mottoes, and a biographical account of the author of the work to which the manuscript refers—will greatly help us in elucidating the subject.

The manuscript is divided into two parts: one bears the name of "Kán Tsippor" ([Hebrew]), "The bird's nest," and treats of the Massorah of the Psalms, i.e., their divisions, accents, vowels, grammatical forms, and letters necessary for the preservation of the text; and the other, the name of "Gán Perákhim" ([Hebrew]), "The garden of flowers," containing poems, special prayers, family records, and descriptions of important events.

The hereditary marks of honour which served to denote the descent and alliances of the Montefiore family consisted of "a lion rampant," "a cedar tree," and "a number of little hills one above the other," each of these emblems being accompanied by a Hebrew inscription. Thus the lion rampant has the motto—

[Hebrew]

HOY GIBOR CAARI LAASOT RATSON AVIKHA SHEBASHEMAIM

"Be strong as a lion to perform the will of thy Father in Heaven."

The hills bear the motto—

[Hebrew]

ESA AYNAI EL HEHARIM MEAIN YAVO EZRI

"(When) I lift up mine eyes unto the hills (I ask) whence cometh my help? [Answer] My help cometh from the Eternal."

And the cedar tree—

[Hebrew]

TSADIK KATAMAR VEFRAKH CAEREZ BALEBANON ISGEH

"The righteous shall flourish like a palm tree; he shall grow like a cedar in Lebanon."

These emblems are precisely the same as those which Sir Moses had in his coat-of-arms, with the exception of the inscriptions. Probably he thought they were too long to be engraved on a signet, and he substituted for them the words "Jerusalem" and "Think and Thank."

The author of the manuscript bears the name of Joseph, and designates himself, on the title-page, as the son of the aged and learned Jacob Montefiore of Pesaro, adding the information that he is a resident of Ancona, and a son-in-law of the Rev. Isaac Elcostantin, the spiritual head of the Hebrew congregation in that place. The manuscript bears the date of 5501 a.m.—1740.

In his biography, the author, after rendering thanks to Heaven for numerous mercies which had been bestowed on him, gives the following account of himself and family:—

"I was eleven years old when I was called upon to assist, conjointly with my three brothers, Moses, Raphael, and Mazliakh, and five sisters, in providing for the maintenance of the family." Moses, the eldest of his brothers, died at the age of thirty-two, and Joseph (the biographer) entered the business of Sabbati Zevi Morini of Pesaro. Being prosperous in his commercial pursuits, he provided for his sisters, probably by giving to each of them a suitable dowry. One of them, Flaminia by name, became the wife of a celebrated preacher, Nathaniel Levi, the minister of the congregation of Pesaro.

The father, Jacob Montefiore, died at the age of eighty-three, and his sons went into business with a certain Cartoni of Lisina. They appear at first to have met with success, but the sudden death of the head of the firm caused the collapse of the business.

Joseph Montefiore subsequently married Justa or Justina, the granddaughter of the Rev. Abraham Elcostantin of Ancona. With a view of carrying on their business to greater advantage the brothers separated and removed to different parts of Italy, and Joseph himself, guided by the counsel of his wife, left Pesaro for Ancona for a similar purpose.

His brother-in-law died at that time in Modena, and Joseph was in a sufficiently prosperous position to be able to assist the widow and her children.

The latter grew up and married. One of them, a daughter,[Pg 8] went with her husband, Samuel Nachman, to Jerusalem, where, from religious motives, they settled.

One of his nephews, Nathaniel Montefiore, became a distinguished poet, and the manuscript in question contains a very beautiful composition of his in praise of the book (Kán Tsippor) and its author.

Joseph Montefiore resided for some time in Rome, also in Fano. There are prayers in the book which he composed during his stay in each of those places.

From these statements it would appear that the family of Montefiore, from which Sir Moses descended, first came to Pesaro.

Signor P. M. Arcantoni, the Syndic of the Municipality of Montefiore dell'aso, in the province of Ascoli-Picerno, expressed his strong belief, on the occasion of his offering to Sir Moses the congratulations of the commune on his completing the hundredth year of his life, that the ancestors of Sir Moses had settled in that place.

From Ancona, as has been stated, several members of the Montefiore family came to Leghorn, from which city at a very early period they emigrated to England.

The grandfather of Sir Moses, Moses Haim (or Vita) Montefiore, and his grandmother, Esther Racah, a daughter of Mássă'ood Racah of Leghorn, also left Italy and settled in London, where their son Joseph (born 15th October 1759, died 11th January 1804) married Rachel, the daughter of Abraham Lumbroso de Mattos Mocatta, who became the mother of Sir Moses.

They resided after their marriage at No. 3 Kennington Terrace, Vauxhall, and were blessed with eight children, three sons, Moses (the subject of these memoirs), Abraham, and Horatio, and five daughters, Sarah, Esther, Abigail, Rebecca, and Justina.

Abraham first married a daughter of Mr George Hall, of the London Stock Exchange; on her death, he married Henrietta Rothschild, a sister of the late N. M. Rothschild, by whom he had two sons, Joseph Meyer of Worth Park, and Nathaniel Meyer of Coldeast, and two daughters, Charlotte and Louise. The latter became the wife of Sir Antony de Rothschild.

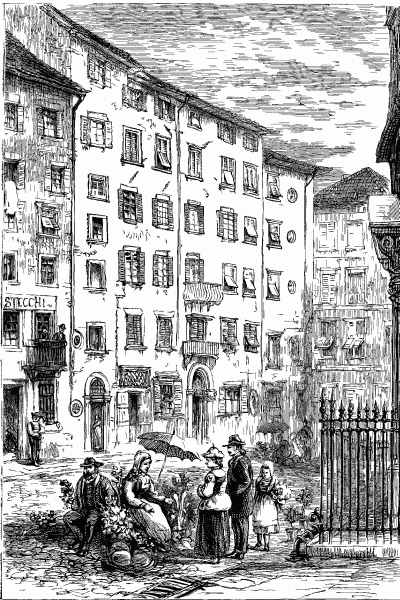

House at Leghorn in which Sir Moses was born.

House at Leghorn in which Sir Moses was born.Horatio married Sarah, a daughter of David Mocatta, by [Pg 9]whom he had six sons, one of whom (Mr Emanuel Montefiore) is now a lieutenant-colonel in the British Army, and six daughters. After her death he married a daughter of Abraham Montefiore.

Sarah, the eldest daughter of Joseph and Rachel Montefiore, became the wife of Mr Solomon Sebag, and was the mother of Mr Joseph Sebag (now J. Sebag-Montefiore) and of Mrs Jemima Guadalla, who is married to Mr Haim Guadalla. After the death of her husband, Mrs Sebag married Mr Moses Asher Goldsmid, the brother of Sir Isaac Goldsmid.

Esther, the second daughter, unfortunately lost her life at the age of fifteen through an accident she met with during a fire that broke out in the house.

Abigail, the third, married Mr Benjamin Gompertz, a distinguished mathematician.

Rebecca, the fourth, married Mr Joseph Salomons, a son of Levi Salomons, of Crosby Square, father of the late Sir David Salomons, Bart.

Justina, the fifth, became the wife of Mr Benjamin Cohen, the brother of Lady Montefiore, and mother of Mr Arthur Cohen, Q. C., M. P., and Mr Nathaniel B. Cohen.

The reader is now invited to retrace his steps, for it is to Moses, the first-born son of Joseph and Rachel Montefiore, that I have to direct his attention. He must leave No. 3 Kennington Terrace and follow me in imagination to Leghorn.

Mr Joseph Montefiore having some business in that city, informed his wife of his intention to proceed to Italy, and Mrs Montefiore prevailed upon him to take her with him.

After they arrived at Leghorn, we find them in the house of Signer Moses Haim Racah, celebrating the happy event of the birth of a son, destined to become the champion of Israel.

The festivity on the day of naming (the eighth day after the birth of a son) is generally an occasion which brings together relatives, friends, heads of the congregation, and officers of the Synagogue. Offerings are made by all present for charitable institutions, and prayers recited for the life and prosperity of the child. It is therefore not a matter of surprise that there was a large assembly of the Hebrew community of Leghorn on that occasion.

Signor Racah, being his great-uncle, performed the duties of[Pg 10] godfather and ever from that day, and up to the year of his death, he evinced the liveliest interest in the welfare of his godson; when the latter was grown up the affection proved mutual.

Sir Moses when speaking of him used to say that he had greatly endeared himself to the people in Leghorn by his abilities and high character. He cherished the most benevolent feelings towards all good and honest men, and often, in times of grief and calamity, rendered help and consolation to all classes of the community. Sir Moses held him in great veneration, and during his stay in Italy gave special orders to have a copy of his likeness procured for him. A facsimile of the portrait is here given, with an inscription in Sir Moses' own handwriting.

In his will, Sir Moses, referring to him and to the Synagogue at Leghorn, thus expresses himself—

"To the trustees of the Synagogue at Leghorn in Italy, of which my honoured godfather (deceased) was a member, in augmentation of the fund for repairing that building, I bequeath £500; and to the same trustees, as a fund for keeping in repair the tomb of my said godfather and my godmother, Esther Racah, his wife, £200."

Two or three years before his death, Sir Moses ordered a coloured drawing of these tombs, with a complete copy of the epitaphs, to be sent to him, and it is now preserved in the library of the College at Ramsgate.

After a stay of several months at Leghorn, Mr and Mrs Montefiore returned to England. I have often heard descriptions of that homeward journey from Mrs Montefiore, when she used to visit her son at Park Lane.

"Moses," she said, "was a beautiful, strong, and very tall child, but yet on our return journey to England, during a severe winter, I was unwilling to entrust him to a stranger; I myself acted as his nurse, and many and many a time I felt the greatest discomfort through not having more than a cup of coffee, bread and butter, and a few eggs for my diet." "No meat of any description," she added, "passed my lips; my husband and myself being strict observers of the Scriptural injunctions as to diet." "But I am now," she said, with a pleasant smile, "amply repaid for the inconvenience I then had to endure." "What I thought a great privation, in no way affected the state of my health, nor that of the child; and I feel at present the greatest satisfaction[Pg 11] on account of my having strictly adhered to that which I thought was right."

Moses Racah of Leghorn, Godfather and Great Uncle

of Sir Moses. See Vol. I., page 10.

Moses Racah of Leghorn, Godfather and Great Uncle

of Sir Moses. See Vol. I., page 10.

In the course of time several more children were born to them, all of whom they reared most tenderly, and over whose education they watched with the greatest care. They had the happiness of seeing them grow up in health and strength, endowed with excellent qualities, Moses, the eldest, and the subject of these memoirs, being already conspicuous for his strength of understanding and kindness of disposition. They continued for many years to reside at Kennington Terrace, Vauxhall, in the same house in which they took up their residence immediately after their marriage. After their death it was occupied by members of their family till a few years ago, when it passed into the hands of strangers.

It was there that Mr Benjamin Gompertz (the author of the "Principles and Application of Imaginary Quantities") resided and the mother of Sir Moses breathed her last.

Joseph Eliahu, his father, was a well educated and God-fearing man, upright in all his dealings. He was extremely fond of botany and gardening. There is still in the library of Lady Montefiore's Theological College at Ramsgate, a book which formerly belonged to him, and in which remarks on the cultivation of plants are written in his own handwriting.

Sir Moses, when speaking of him, used to say, "He was at one time of a most cheerful disposition, but after he had the misfortune to lose one of his daughters at a fire which occurred in his house, he was never seen to smile."[Pg 12]

At an early age, we find young Moses Montefiore attending school in the neighbourhood of Kennington. After he had completed his elementary studies, he was removed to a more advanced class in another school, where he began to evince a great desire to cultivate his mind, independently of his class lessons. He was observed to copy short moral sentences from books falling into his hands, or interesting accounts of important events, which he endeavoured to commit to memory.

Afterwards, as he grew up in life, this became a habit with him, which he did not relinquish even when he had attained the age of ninety years. His diaries all contain either at the beginning or the end of the record of his day's work, some beautiful lines of poetry referring to moral or literary subjects: mostly quotations or extracts from standard works. Young Montefiore showed on all occasions the greatest respect for his teachers, bowing submissively to their authority in all cases of dispute between his fellow-students and himself.

He was acknowledged to be most frank and loyal in all his intercourse with his superiors. The respect due to constituted authorities he always used to consider, when he had become a man in active life, as a sacred duty. He was in the habit of saying, in the words of the royal philosopher, "Fear thou the Lord and the King, and meddle not with them that are given to change." Whatever might be his private opinion on any subject, he would in all his public and private transactions be guided only by the decision of an acknowledged authority.

Montefiore did not remain many years at school. There was at that time no prospect for him to enter life as a professor at a university, or as a member of the bar. There was no[Pg 13] sphere of work open to him in any of the professions; and even to enter the medical profession would have been difficult. There was nothing left for him, therefore, but to enter a commercial career. He used often to speak about the days of his apprenticeship in the business of one of their neighbours in Kennington, and how hard he had to work; when subsequently he was in a counting-house in the city, the hours were late, and he sometimes had to take letters to the post on the stroke of midnight. There were no copying machines, and all letters had to be copied by hand. He also spoke of the great distance he had to walk every night from the city to Kennington Terrace, during the cold winter months as well as in the summer time. There were then no omnibuses or other conveyances at hand such as we have now, and if there had been, he was of too saving a disposition to make any unnecessary outlay on his own person; he used to keep a strict account of the smallest item of his expenses. It was not with the object of complaining, or of regretting his early mode of life that he gave his friends these descriptions; his object was to impress on the mind of the rising generation the necessity of working hard and spending little, in order to make their way in the world.

By his habits of industry, by his strict compliance with the instructions of his superiors, and more especially by his own clear judgment in all matters connected with the business entrusted to him, he soon succeeded in obtaining promotion.

Having had the opportunity of seeing business transactions among brokers on the Stock Exchange, he decided upon securing for himself the privilege of being one of the limited number of Jewish brokers. According to the law of England at that time only twelve such brokers could be admitted, but Moses Montefiore had the satisfaction of soon seeing himself in possession of the much-coveted privilege. He took an office, and this owing to the prosperity with which his straightforward dealing and courteous manners were rewarded, he soon had to change for a larger one, which again he did not keep long. As his business had now to be conducted near the bank, he took up his quarters in Bartholomew Lane, where he remained to the last day of his life. It was there, after nearly the whole of that thoroughfare had become the property of the Alliance Life and Fire Assurance Company, and the houses had been rebuilt, that many an[Pg 14] important meeting of the Board of Deputies of British Jews and other boards of benevolent institutions was held; and the very book-case, in which all important papers connected with his business in that office were preserved, is now in one of the houses of Lady Montefiore's College, where he used now and then to take his breakfast on a Sabbath morning, when it was his intention to be present at a lecture in the college.

His brother Abraham, seeing young Moses successful in business, subsequently joined him as a partner, and the firm of Montefiore Bros. soon became known in England as one entitled to the respect of all honourable men.

However profitable or urgent the business may have been, the moment the time drew near, when it was necessary to prepare for the Sabbath or solemn festivals, Moses Montefiore quitted his office, and nothing could ever induce him to remain.

Sir Moses was scrupulously honourable in all his transactions, and it is a noteworthy fact, that during all his long life no whisper was ever heard against his reputation, although he was intimately connected with the management of financial and commercial undertakings of great magnitude and international character. His name stood so high, that thousands of people from all parts of the world entrusted him with money to be forwarded to the Holy Land, or for other charitable purposes, never asking for a receipt, and in many instances leaving the distribution of it to his own discretion.

In the year 1809, in the reign of George III., an act of parliament was passed enabling His Majesty to establish a local Militia Force for the defence of the country. Young Montefiore, who was then twenty-five years old, having attained his majority in 1805, deemed it his duty to be one of the first volunteers. Loyalty to the country in which he lived and prospered, and sincere devotion to his king, afterwards proved to be special traits in his character. In all foreign countries whither his philanthropic missions subsequently led him, his addresses to the people and his counsels, even to those who suffered under heavy oppression, contained exhortations to them to remain firm in their loyalty to their government.

We must now salute him as Captain Montefiore, for thus we find him styled, on a card among his papers,

Third Surrey Local Militia, Colonel Alcock, No. I,

Seventh Company.

"Captain Montefiore."

Lady Montefiore when young, copied from an oil

painting in the Montefiore College, Ramsgate. See Vol. I., page

15.

Lady Montefiore when young, copied from an oil

painting in the Montefiore College, Ramsgate. See Vol. I., page

15.

There are still in the Gothic library, at East Cliff Lodge, details of guard mounted by the 3rd Regiment of Surrey Local Militia, standing orders, &c., also the orderly books showing that he was in the service from the year 1810 to 1814.

On the 22nd February in the latter year, after the parade on Duppas Hill, Croydon, when the regiment arrived at the depôt, the commanding officers of companies had to receive the signatures of all those who wished to extend their services, when called upon for any period in that same year not exceeding forty-two days. The feeling of the regiment on the subject was obtained in less time than was anticipated, and the commanding officer ordered the men to be paid and dismissed immediately.

Sir Moses used to say, when speaking to his friends on this subject, "I did all in my power to persuade my company to re-enlist, but I was not successful."

In the same year, he took lessons in sounding the bugle, and also devoted several hours a week to the study of French; it appears that he would not allow one hour of the day to pass without endeavouring to acquire some useful art or knowledge.

He was very particular in not missing a lesson, and entered them all in his diary of the year 1814.

In the midst of business, military duties, and studies, in which he passed the five years, 1810 to 1814, there was one date which he most justly considered the happiest of his life.

I am alluding to the 10th of June 1812 (corresponding, in that year, to the 30th of Siván, 5573 a.m., according to the Hebrew date), on which day he was permitted to take to himself as a partner in life, Judith, the daughter of Levi Barent Cohen.

He thoroughly appreciated the great blessing which that union brought upon him. Henceforth, for every important act of his, where the choice was left to him, whether it was the laying of a foundation stone for a house of prayer, a charitable institution, or a business office, he invariably fixed the date on the anniversary of his wedding day. Setting out on an important mission in the month of June, he would, when a short delay was[Pg 16] immaterial, defer it to the anniversary of his wedding. This was not, as some might suppose, from mere superstition, for in all his doings he was anxious to trust to the will of God alone; it was with the idea of uniting every important act in his life with one which made his existence on earth, as he affirmed, a heavenly paradise.

His own words, taken from the diary of 1844, will best express his feelings on the subject.

"On this happy day, the 10th of June," he writes, "thirty-two years have passed since the Almighty God of Israel, in His great goodness, blessed me with my dear Judith, and for ever shall I be most truly grateful for this blessing, the great cause of my happiness through life. From the first day of our happy union to this hour I have had every reason for increased love and esteem, and truly may I say, each succeeding year has brought with it greater proofs of her admirable character. A better and kinder wife never existed, one whose whole study has been to render her husband good and happy. May the God of our fathers bestow upon her His blessing, with life, health, and every other felicity. Amen."

As a lasting remembrance of the day he treasured the prayer-shawl which, according to the custom (in Spanish and Portuguese Hebrew communities), had been held over his head and that of his bride during the marriage ceremony and the offering up of the prayers.

In compliance with his wish the same shawl was again put over his head when his brethren performed the melancholy duty of depositing his mortal remains in their last resting-place.

But I will not further digress, and I resume my narrative of his happy life after his union with his beloved wife.

Henceforth the reader may consider them as one person, and every act of benevolence recorded further on in these Memoirs must be regarded as an emanation of the generous and kindly impulses which so abundantly filled the hearts of both.

In order to indicate the places to which the young couple would resort after the duties of the day, I need only remind the reader of the residences of their numerous relatives, with whom they were always on affectionate terms. At Highgate, Clapham, Lavender Hill, and Hastings, in all of these places they were most heartily welcomed, and they often went there to dine, take tea,[Pg 17] or spend a few days in the family circle. But the place to which they repaired for the enjoyment of a complete rest, or for considering and maturing a plan for some very great and important object, was an insignificant little spot of the name of "Smithembottom" in Surrey.

They used to go there on Sunday and remain until the next day, sometimes until the middle of the week, occasionally inviting a friend to join them. They greatly enjoyed the walk over hills, while forming pleasing anticipations of the future; and they always found on their return to the little inn, an excellent dinner, which their servants had brought with them from London—never forgetting, by the order of their master, a few bottles of his choice wine. "Wine, good and pure wine," Mr Montefiore used to say, "God has given to man to cheer him up when borne down by grief and sorrow; it gladdens his heart, and causes him to render thanks to heaven for mercies conferred upon him." In holy writ we find "give wine unto those that be of heavy heart;" also, "wine maketh glad the heart of man." No sanctification of our Sabbaths and festivals, and no union between two loving hearts, can be solemnised, without partaking of wine over which the blessing has been pronounced.

It was his desire to be happy, and make others around him happy, for such he said was the will of God (Deut. xxvi. II). When certain friends of his, who intended taking the total abstinence pledge, ventured to raise an argument on the desirability of his substituting water for wine, he would reply in the words which the vine said to the trees when they came to anoint him as king over them, "Should I leave my wine which cheereth God and man" (Judges ix. 13)? His friends smiled at this reasoning, and on their next visit to him drank to each other's health in the choice wine of his cellar.

I invariably heard him pronounce the blessing before he touched the exhilarating beverage, in such a tone as to leave no doubt in the minds of those present that he fully appreciated this gift of God.

He never gave up the habit of taking wine himself, and it was his greatest pleasure to see his friends enjoy it with him. To the sick and the poor he would frequently send large quantities.

The year 1812 passed very happily. Every member of the family was delighted with the young couple. They said, "such a[Pg 18] suitable union of two young people had not been seen for many years." In No. 4 New Court, where they took up their abode, they had Mr N. M. Rothschild their brother-in-law (in whose financial operations Montefiore was greatly interested), for a neighbour and friend. Young Mrs Montefiore had but a short distance to walk to see her parents, at Angel Court, Throgmorton Street, where Mrs Barent Levi Cohen now lived. The Stock Exchange and the Bank being in their immediate neighbourhood, where all their relatives had business transactions every day in the week except Sabbath and festivals, they often had the opportunity of seeing the whole family circle in their house.[Pg 19]

I am now at the starting point of my narrative of the public life and work of Sir Moses and Lady Montefiore in connection more especially with the communities of their own race, and this I propose to give in the form of extracts from their diaries. These extracts contain the most material references to important events, accompanied by explanatory remarks of my own. With a view of making the reader acquainted with the passing opinions and feelings of Sir Moses and Lady Montefiore and their earnestness of purpose and energy in every good cause, as well as with a desire to draw attention to the variety and multiplicity of the work they would accomplish in a single day, I shall frequently give these entries as I find them, in brief and at times abrupt sentences.

1813 (5573 a.m.).—Owing to the eventful vicissitudes of European wars, the greatest activity prevails on the Stock Exchange. Mr Montefiore is in constant intercourse with Mr N. M. Rothschild, through whose prudence and judicious recommendations with regard to the Bullion Market and Foreign Exchanges, he is enabled not only to avoid hazardous monetary transactions, but also to make successful ventures in these difficult times.

1814 (5574 a.m.).—The first peace in Paris is signed. The allied sovereigns visit England, and are received by the Prince Regent. Great festivities in the city, while considerable excitement prevails in all financial circles. Commerce is stagnant; taxation excessive, in consequence of the great debt the country had incurred during the war; the labouring classes cry out; food is scarce; there is no demand for labour, and wages are low. Nevertheless, Mr Montefiore and his wife entertain the[Pg 20] hope of a continuance of peace, which, they say, will soon remedy all evils. They frequently visit Highgate, where Mr N. M. Rothschild has his country house; go to Hastings, where their brother-in-law Mr S. M. Samuel, has taken a summer residence, and visit their mother, Mrs Montefiore, at Kennington Terrace. They contrive to devote a portion of the day or evening to the study of the French language and literature. Mr Montefiore, as captain of the local militia, continues taking lessons on the bugle.

1815 (5575 a.m.).—Mr Montefiore agrees with Lord Mayor Birch (grandfather of Dr Samuel Birch of the British Museum) to pay £600, for the transfer to himself, of Medina's Broker's medal (at that time the few Jewish brokers admitted had to pay an extraordinarily high fee for the privilege); he is engaged in his financial transactions with Mr N. M. Rothschild, and goes, in the interest of the latter and in his own, to Dunkirk and Yarmouth. On his return he frequently attends the meetings of the representatives of the Spanish and Portuguese synagogues; checks and signs the synagogue books, as treasurer, and is present at the meetings of a committee, representing four Hebrew congregations in London, for devising proper regulations to ensure the provision of meat prepared in accordance with Scriptural injunctions.

1816 (5576 a.m.).—He frequently attends the meetings of the Velhos (Elders) of the Spanish and Portuguese community, and the society for granting marriage portions to orphans. His work in connection with finance daily increases.

Great agitation prevails throughout the country; the Government having, in the previous year, passed a Corn Act to favour the English farmer, forbidding the importation of foreign grain, the price of wheat had reached 80s. per quarter; political societies, under the name of "Hampden Clubs," are formed all over the country. There is a cry for reform in the House of Commons; the Ministry, influenced by Lord Castlereagh, refuses all change; the price of wheat continues to rise daily after the peace.

Financiers feel very anxious about the result, but Mr and Mrs Montefiore, less apprehensive of serious disturbances, and desirous of change of scene and climate, purpose setting out to visit France and Italy.[Pg 21]

1816 (5576 a.m.).—They travel in France and Italy, visit public institutions, and make it a rule to see every object of interest. They take notice and make memoranda of the explanations given them by their Ciceroni, independently of the information derived from guide-books; they frequent theatres and operas as well as hospitals and schools. A beautiful and comfortable travelling chariot, procured in Paris from Beaupré, a famous coach builder, at the price of 4072 francs, and abundant provisions for themselves and friends, making them independent of inferior hotels for food, make their travels most agreeable to themselves and to all who accompany them.

Mr Montefiore and his wife were not only diligent observers of whatever they saw, but also possessed the good quality of never objecting to any difficulties to be overcome in order to add to their stock of knowledge or experiences.

During their travels in France and Italy, their pleasure was greatly enhanced by the kind attention they received at the hands of their friends, especially in Paris, where Mr Solomon de Rothschild and all the members of the family vied with each other in their efforts to make their stay as agreeable as possible.

At Lausanne, Mr Montefiore was very ill for three days with rheumatism in the face and ear, but he soon recovered, and was able to continue his journey. On August the 30th, after an absence of three months from England, they returned and arrived safely at Dover.

On September 20th he is appointed treasurer to the "Beth Holim" hospital of the Spanish and Portuguese Hebrew community.

November 26th.—A private account is opened with Jones, Lloyd & Co. and the Bank of England; on the 29th of the same month he dissolves partnership with his brother Abraham, "God grant," he says, "it may prove fortunate for us both."

1817 (5577 a.m.).—This was a year of riot in England; in spite of the Royal proclamation against unlawful assemblages the riots increased; the Habeas Corpus Act was suspended, but the seditious meetings continued. A motion in the House of Commons for reform had only seventy-seven supporters, two hundred and sixty-six voting for its rejection. Mr Montefiore,[Pg 22] like most financiers in London, was in constant anxiety, his state of health suffered, and it was desirable for him to leave England again for change of climate.

He completes the purchase of Tinley Lodge farm on July 30th. On October 7th he signs his will; and on the 13th of the same month, accompanied by his wife and several of their relatives, sets out on his second journey to France and Italy. On the road, he and Mrs Montefiore resume their Hebrew studies. They visit Paris, Lyons, Turin, Milan, and Carrara; the latter place being of special interest to them on account of their meeting with persons who had been connected in business transactions with Mr Montefiore's father.

1818 (5578 a.m.).—They arrive on the 1st of January at Leghorn, and meet several members of their family. They visit the house where Mr Montefiore was born, and are welcomed there by Mr Isaac Piccioto, who occupied the house at that time; they proceed thence to the burial ground to see the tomb of their uncle Racah, and on the following day leave for Pisa.

There they visit the house and garden of the said uncle Racah, Mr Montefiore observing, that it is a good garden, but a small house; thence they continue their journey to Sienna.

"I had a dispute," he says, "with the postmaster at a place called Bobzena, and was compelled to go to the Governor, who sent with me two gendarmes to settle the affair." "The road to Viterbo," he observes, "I found very dangerous; the country terribly dreary, wild and mountainous, with terrific caverns and great forests."

"On the 15th of January," he continues, "we became greatly alarmed by the vicinity of robbers on the road, and I had to walk upwards of seven miles behind the carriage until we arrived at Rome, whither we had been escorted by two gendarmes."

"In Rome," he says, "we saw this time in the Church of St John, the gate of bronze said to be that of the temple of Jerusalem; we also revisited the workshop of Canova, his studio, and saw all that a traveller could possibly see when under the guidance of a clever cicerone.

"We left Rome on the 11th of February, and passed a man lying dead on the road; he had been murdered in the night. This incident damped our spirits and rendered the journey, which would otherwise have been delightful, rather triste."[Pg 23]

On the 3rd of April they arrive at Frankfort-on-the-Main; in May they are again in London, and on the 13st inst., Mr Montefiore, dismissing from his mind (for the time) all impressions of gay France and smiling Italy, is to be found in the house of mourning, expressing his sympathy with the bereaved, and rendering comfort by the material help which he offers in the hour of need.

It is in the house of a devoted minister of his congregation, the Rev. Hazan Shalom, that we find him now performing the duties of a Lavadore, preparing the dead for its last resting-place.

The pleasures of his last journey, and the change of scene and climate appear to have greatly invigorated him, for we find him on another mournful occasion, exhibiting a degree of physical strength such as is seldom met with.

His mother-in-law having been taken ill on Saturday, the 14th of November, he went on foot from Smithembottom to Town, a walk of five hours, in order to avoid breaking one of the commandments, by riding in a carriage on the Sabbath. Unfortunately on his arrival, he found she had already expired. Prompted by religious fervour and attachment to the family, he attended during the first seven days the house of mourning, where all the relatives of the deceased assembled, morning and evening, for devotional exercises, and, with a view of devoting the rest of the day to the furtherance of some good cause, he remained in the city to be present at all the meetings of the representatives of his community.

In the month of December he went down to Brighton to intercede with General Bloomfield for three convicts. (The particulars of the case are not given in the diary), and on his return he resumed his usual financial pursuits.

1818 (5579 a.m.). He is elected President of the Spanish and Portuguese congregation. "I am resolved," he says, "to serve the office unbiassed, and to the best of my conscience." Mr Montefiore keeps his word faithfully, for he attends punctually all the meetings of the elders; and, on several occasions, goes about in a post-chaise to collect from his friends and acquaintances contributions towards the fund required for the hospital "Beth Holim" of his community.

This was the year in which the political crisis came, when public meetings, in favour of Parliamentary reform were held[Pg 24] everywhere, and Parliament passed six Acts restricting public liberty. In the midst of these troubles, on the 24th of May, the Princess Victoria, daughter of the Duke of Kent, the fourth son of the king, was born at Kensington Palace.

1820 (5580 a.m.). The Diary opens this year with observations on the life of man, and with a view of affording the reader an opportunity of reflecting on Mr Montefiore's character, I append a record of his pursuits such as we seldom meet with in a man in the prime of life, at the age of 30.

In full enjoyment of health, wealth, and every pleasure a man could possibly desire, he thus writes on the first page:—

"He who builds his hopes in the air of men's fair looks,

Lives like a drunken sailor on the mast,

Ready with every nod to tumble down

Into the fatal bowels of the deep.

"With moderate blessings be content,

Nor idly grasp at every shade,

Peace, competence, a life well spent,

Are blessings that can never fade;

And he that weakly sighs for more

Augments his misery, not his store."

[Pg 25]

Mr Montefiore's occupations may best be described in his own words, and may furnish a useful hint to those who neglect to keep an account of the way in which their time is spent. He writes:—

"With God's blessing,—Rise, say prayers at 7 o'clock. Breakfast at 9. Attend the Stock Exchange, if in London, 10. Dinner, 5. Read, write, and learn, if possible, Hebrew and French, 6. Read Bible and say prayers, 10. Then retire.

"Monday and Thursday mornings attend the Synagogue. Tuesday and Thursday evenings for visiting."

"I attended," he says, "many meetings at the City of London Tavern, also several charitable meetings at Bevis Marks, in connection with the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue; sometimes passing the whole day there from ten in the morning till half-past eleven at night (January 25, 1820), excepting two hours for dinner in the Committee room; answered in the evening 350 petitions from poor women, and also made frequent visits to the Villa Real School."

In the course of the year he went to Cambridge and to Norwich, visiting many of the colleges, the Fitzwilliam Museum, and other interesting institutions, and on February the 16th he attended the funeral sermon of his late Majesty George the Third (who died on the 29th of January).

He often went to his farm, near Tinley Lodge, and sometimes for special recreation to the English Opera, together with his wife and members of the family, always finding time for work and pleasure alike.

"Mr N. M. Rothschild," he records in an entry, "being taken ill, I stayed with him several days at Stamford Hill."[Pg 26]

Subsequently Mr Montefiore had some very important business in connection with a loan, and experienced much uneasiness, owing to a riot among the soldiers of the third regiment of the Guards, which, no doubt, affected the financial world.

He frequently went to the House of Commons and the House of Lords to ascertain the state of politics, and the progress of the Jews Emancipation Bill in particular; for the Roman Catholic Emancipation Bill, which, side-by-side with Parliamentary reform, and the demand for free trade, was at that time agitating the public mind, naturally prompted the Jews to bring before the House their own grievances. Mr Montefiore also visited the Female Freemasons' Charity, and generously supported the craft which, as has been said, has had a being "ever since symmetry began and harmony displayed her charms."

October 30.—An important event in his financial career takes place: he gives up his counting-house.

1821 (5581 a.m.)—The first day of this year corresponding with the Hebrew date, Tebet 28, on which his father, he writes, entered into eternal glory, 11th of January 1804 (5564 a.m.), he repairs morning and evening to the house of prayer, offering up the customary prayer in memory of the dead.

"I visited his tomb, distributing gifts to the poor and needy, and on my return passed the whole of the day in fasting and religious meditation."

The next entries refer to his frequent visits to the hospital, "Beth Holim," going to see King George IV. at Drury Lane, dining with the Directors of the Atlas Fire Assurance Company at the Albion, going afterwards with the Lord Mayor of Dublin to Covent Garden Theatre to see His Majesty again, his excursions to the country, together with his wife, and their visits to Finchley Lodge Farm, where they sometimes pass the day together. On his return to London, he attends, as in the preceding year, the meetings of the elders of his community and those of the communal institutions.

On 8th May they set out for Scotland. Of this tour Mrs Montefiore kept an interesting journal, which not only describes the state of the country and the mode of travelling sixty six years ago, but shows her good temper under difficulties, her[Pg 27] gratitude to Providence for the blessings they enjoyed, and for their safety after apparent danger, as also her keen appreciation of the beauties of nature and art. It contains, however, no information likely to be serviceable to the present generation travelling in Scotland.

In October we meet them again in London, in the House of Prayer, offering up thanks for their safe return from Scotland. During the rest of the year Mr Montefiore resumed his usual occupations, always combining the work of finance with that intended for the welfare of his community and charitable institutions of all classes of society, while Mrs Montefiore devoted herself to responding to every appeal for help commensurately with the merit of the case, comforting every sufferer by her kind acts of sympathy, and promoting peace and harmony among those whose friendship seemed likely to be interrupted.

An incident which, at the time, afforded Mr Montefiore special gratification, he refers to as follows:—

"I was present, on the Feast of Haunkah (the anniversary of the victory of the Maccabees), at a discourse delivered by the spiritual head of the congregation, in the College of the Spanish and Portuguese Hebrew Community. The interest was greatly enhanced by the completion of the study of one of their theological books in the presence of all the students. The latter evinced great love for their study, and appeared well acquainted with the subject to which the lecturer referred."

Mrs Montefiore presented each student with a generous gift, as an encouragement to continued zeal in their work.

1822 (5582 a.m.).—He agrees to rent East Cliff Lodge for one year from the 15th of April, for £550 clear, and signs the agreement on 12th February.

On the eve of the Day of Atonement, in the presence of his assembled friends, he completes, by adding the last verse in his own handwriting, a scroll of the Pentateuch, for the use of the Synagogue, offering on the following day £140 for the benefit of various charitable institutions of his community as a token of his appreciation of the Synagogue Service.

The depressed state of trade in this and the preceding year, owing to serious apprehensions of war, had caused a great diminution in the importation and manufacture of goods, so that much anxiety prevailed. Referring to this subject, Mr Montefiore[Pg 28] makes an entry to the effect that a statement had been made in high quarters by the Duke of Wellington, that peace would be maintained, in consequence of which, says Mr Montefiore, all the public funds rose.

1823 (5583 a.m.).—Opens with a joyous event in the family. His brother Horatio, on the first of January, marries a daughter of David Mocatta, thus allying more closely the two most prominent families in the Hebrew community.

August 20th.—Mr and Mrs Montefiore leave England for the third time for France, Germany, and Italy.

The entry this day refers to something which happened to him seventeen years previously (1806), (for obvious reasons I do not give the name, which is written in full in the diary):—"N. N. robbed me of all and more than I had. Blessed be the Almighty, that He has not suffered my enemies to triumph over me."

On their arrival at Rome they find Mr Abraham Montefiore very ill; much worse, Mr Montefiore says, than they had expected. His critical state induces them to remain with him to the end of the year.

About the same time, his brother Horatio was elected an elder in his synagogue: "affording him many opportunities," Mr Montefiore observes, "to make himself useful to the congregation."

1824 (5584 a.m.).—His brother Abraham continues very ill, but Montefiore can remain with him no longer, his presence being much required in London.

February 13th.—Mr and Mrs Montefiore arrive in London, and on the 17th he again goes to the Stock Exchange, this being the first time for more than a year that he has done so.

July 28th.—The deed of settlement of the Alliance Life Assurance Company is read to the general court. On August 4th he has the gratification of affixing his name to it. "On the same day," he says, evidently with much pleasure, "I have received many applications for shares of the Imperial Continental Gas Association."

The diary introduces the subject of Insurance Companies by quoting the words of Suetonius.

"Suetonius conjectures," Mr Montefiore writes on the first page of the book, "that the Emperor Claudius was the original projector of insurances on ships and merchandise."[Pg 29]

"The first instances of the practice recorded in modern history," he observes, "occur in 1560, in consequence of the extensive wool trade between England and the Netherlands; though it was probably in use before that period, and seems to have been introduced by the Jews in 1182."

"It is treated of in the laws of Oleron, relating to sea affairs, as early as the year 1194."

"About the period of the great fire in London, 1666, an office was established for insuring houses from fire."

This information is probably no novelty to the reader, but my object in quoting it is to show how attentively Mr Montefiore studied every subject connected with his financial and other pursuits. We have in the College library a great variety of books bearing on insurance offices, all of which, it appears, he had at some time consulted for information.

Of both the above companies he was elected president, offices which he held to the last moment of his life. They are now numbered among the most prosperous companies in England.

His presence at the board was always a cause of the highest satisfaction, not only to the directors and shareholders, all of whom appreciated his sound judgment, cautious disposition and energy in the promotion and welfare of the company, but also to all the officers and employees of the respective offices.

In conversing with his friends on this subject, he used to say, "When our companies prosper, I wish to see everyone employed by us, from the highest to the lowest, derive some benefit from them in proportion to the position he occupies in the office." He also strongly advocated the promotion of harmony and friendliness among the officers of the companies, for which purpose, he used annually to give them an excellent dinner in one of the large hotels, inviting several of his personal friends to join them.

When travelling on the Continent, he invariably made a point of visiting every one of the branches of the Imperial Gas Association, making strict enquiries on every subject connected with the operations, and inviting all the officers to his table.

I have frequently (after the year 1839) accompanied him on such occasions, and often wondered at his minute knowledge of every item entered in the books of the respective offices.[Pg 30]

He often gave proof, in the last years of his life, of his special interest in the prosperity of these companies by the exertions he would make in signing every document sent down to him at Ramsgate for that purpose, even when he appeared to experience a difficulty in holding a pen.

He strongly objected to a system of giving high dividends to the shareholders. "Let us be satisfied," he used to say, "with five per cent., so that we may always rest in the full enjoyment of undisturbed life on the firm rock of security,"—the emblem represented on the office seal of the Alliance.

On August the 15th of that year he received a letter from Genoa stating that his brother Abraham was getting worse, and on Saturday, the 28th, he received the sad news of his death, which took place at Lyons whilst on his way back from Cannes.

"It was only in the month of January last," Mr Montefiore says of his brother, "that when his medical attendant recommended him to take a sea voyage, he agreed to go with me to Jerusalem, if I would hire a ship to take us there." "Seize, mortal," Mr Montefiore continues, quoting the words of the poet:

"Seize the transient hour,

Improve each moment as it flies;

Life a short summer—man a flower;

He dies, alas! how soon he dies."

1825 (5855 a.m.).—The lessons he sets for himself this year are given in quotations from authors, the selections showing the reflex of the impressions made on his mind by current events.

The first is an Italian proverb: "Chi parla semina, chi tace racolta," corresponding to the English, "The talker sows, the silent reaps."

Those which follow are from our own moralists:—

"A wise man will desire no more than what he may get justly, use soberly, distribute cheerfully, and live upon contentedly."

"He that loveth a book will never want a faithful friend, a wholesome counsellor, a cheerful companion, or an effective comforter."

"The studies afford nourishment to our youth, delight to our old age, adorn prosperity, supply a refuge in adversity, and are a constant source of pleasure at home; they are no impediment while abroad, and attend us in the night season, in our travels, and in our retirement."[Pg 31]

"He may be well content that need not borrow nor flatter."

He attends this year regularly all the meetings of eight companies or associations: the Alliance British and Foreign Life and Fire Assurance, the Alliance Marine Assurance, the Imperial Continental Gas Association, the Provincial Bank of Ireland, the Imperial Brazilian Mining, the Chilian and Peruvian Mining, the Irish Manufactory, and the British Colonial Silk Company.

With all this, no doubt often very exciting work, he still finds time for attending all the meetings of charitable institutions of which he is a member, more especially those of his own community; while he is often met in the house of mourning performing duties sometimes most painful and distressing to a sympathising heart.

February 11th.—He attends for the first time the General Board of the Provincial Bank of Ireland.

Being now considered an authority of high standing in the financial world, various offers were made to him by promoters to join their companies or become one of their directors. Among these undertakings is one which I will name on account of the interest every man of business now takes in it. I allude to a company which had for its object the cutting of a ship canal for uniting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

He refused the directorship of that gigantic undertaking, which, after having been abandoned for nearly sixty years, was again taken up, under the name of the Panama Canal, by M. de Lesseps.

Thirty years later Mr Montefiore also refused to take a leading part or directorship in the Suez Canal Company, which M. de Lesseps had offered him when in Egypt. I happened to be present at the time when M. de Lesseps called on him with that object. It was in the year 1855, when Mr Montefiore had become Sir Moses Montefiore, and was enjoying the hospitality of his late Highness Said Pasha, who gave him one of his palaces to reside in during his stay at Alexandria.

M. de Lesseps spoke to him for several hours on the subject, but he could not be persuaded that so great an undertaking was destined to be a pecuniary success.