The Project Gutenberg EBook of American Cookery, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: American Cookery

November, 1921

Author: Various

Release Date: July 11, 2008 [EBook #26032]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AMERICAN COOKERY ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Emmy and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Painted by Edw. V. Brewer for Cream of Wheat Co. Copyright by Cream of Wheat Co.

Painted by Edw. V. Brewer for Cream of Wheat Co. Copyright by Cream of Wheat Co.In reality, if the baking powder is not PURE and PERFECT in its leavening qualities, food will be spoiled in spite of skill and care.

RUMFORD contains the phosphate necessary to the building of the bodily tissues, so essential to children.

| CONTENTS FOR NOVEMBER | PAGE | |

| WINDOWS AND THEIR FITMENTS. Ill. | Mary Ann Wheelwright | 251 |

| THE TINY HOUSE. Ill. | Ruth Merton | 255 |

| YOU'RE NOT SUPPOSED TO, JIMMIE | Eva J. DeMarsh | 258 |

| SOMEBODY'S CAT | Ida R. Fargo | 260 |

| HOMING-IT IN AN APARTMENT | Ernest L. Thurston | 263 |

| TO EXPRESS PERSONALITY | Dana Girrioer | 265 |

| EDITORIALS | 270 | |

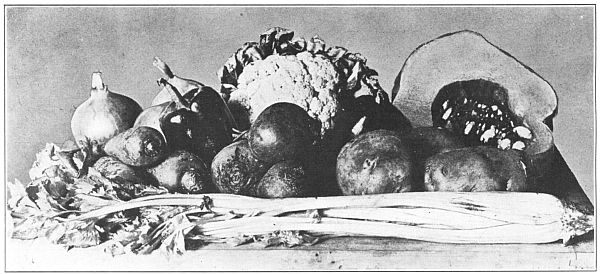

| SEASONABLE-AND-TESTED RECIPES (Illustrated with halftone engravings of prepared dishes) | Janet M. Hill and Mary D. Chambers | 273 |

| MENUS FOR WEEK IN NOVEMBER | 282 | |

| MENUS FOR THANKSGIVING DINNERS | 283 | |

| CONCERNING BREAKFASTS | Alice E. Whitaker | 284 |

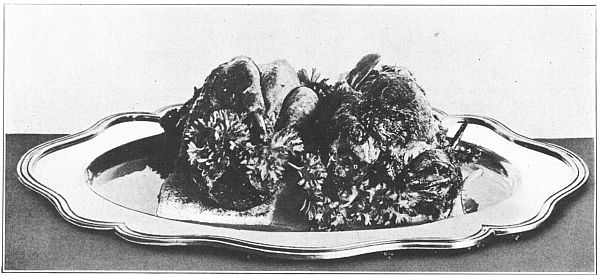

| SOME RECIPES FOR PREPARING POULTRY | Kurt Heppe | 286 |

| POLLY'S THANKSGIVING PARTY | Ella Shannon Bowles | 290 |

| HOME IDEAS AND ECONOMIES:—Vegetable Tarts and Pies—New Ways of Using Milk—Old New England Sweetmeats | 292 | |

| QUERIES AND ANSWERS | 295 | |

| THE SILVER LINING | 310 | |

| $1.50 A YEAR Published Ten Times a Year 15c A Copy Foreign postage 40c additional Entered at Boston post-office as second-class matter Copyright 1921, by THE BOSTON COOKING-SCHOOL MAGAZINE CO. Pope Bldg., 221 Columbus Ave., Boston 17, Mass. |

|

"When it rains—it pours" Discover it for yourselfTO READ about the virtues of Morton

Salt isn't half so pleasant as finding

them out for yourself.

MORTON SALT COMPANY, CHICAGOIt certainly gives you a sense of security and content to find that Morton's won't stick or cake in the package when you want it; that it pours in any weather—always ready; always convenient. You'll like its distinct bracing flavor too. Better keep a couple of packages always handy. "The Salt of the Earth" |

| PAGE | |

| Concerning Breakfasts | 284 |

| Editorials | 270 |

| Home Ideas and Economies | 292 |

| Homing-It in an Apartment | 263 |

| Menus | 282, 283 |

| Polly's Thanksgiving Party | 290 |

| Silver Lining, The | 310 |

| Some Recipes for Preparing Poultry | 286 |

| Somebody's Cat | 260 |

| Tiny House, The | 255 |

| To Express Personality | 265 |

| Windows and Their Fitments | 251 |

| You're not Supposed to, Jimmie | 258 |

| Beef, Rib Roast of, with Yorkshire Pudding. Ill. | 277 |

| Boudin Blanc | 281 |

| Bread, Stirred Brown | 280 |

| Brother Jonathan | 275 |

| Cake, Pyramid Birthday | 280 |

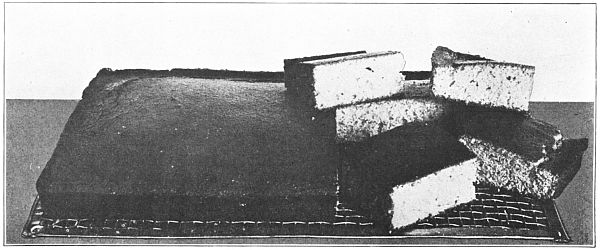

| Cake, Thanksgiving Corn. Ill. | 277 |

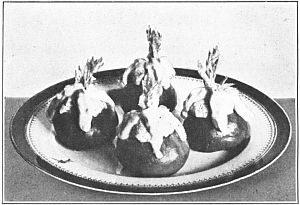

| Chicken, Guinea. Ill. | 276 |

| Cookies, Pilgrim. Ill. | 279 |

| Cucumbers and Tomatoes, Sautéed | 281 |

| Cutlets, Marinated | 276 |

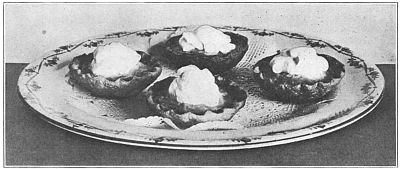

| Fanchonettes, Pumpkin. Ill. | 279 |

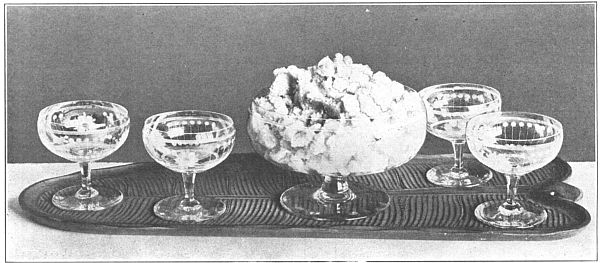

| Frappé, Sweet Cider. Ill. | 278 |

| Fruit, Suprême | 299 |

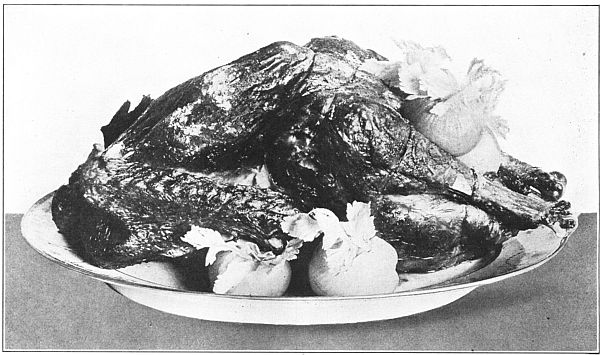

| Garnish for Roast Turkey | 274 |

| Jelly, Apple Mint, for Roast Lamb | 276 |

| Pancakes, Swedish, with Aigre-Doux Sauce | 280 |

| Parsnips, Dry Deviled | 278 |

| Pie, Fig-and-Cranberry | 278 |

| Potage Parmentier | 273 |

| Pudding, King's, with Apple Sauce | 278 |

| Pudding, Thanksgiving | 277 |

| Pudding, Yorkshire | 277 |

| Punch, Coffee Fruit | 278 |

| Purée, Oyster-and-Onion | 274 |

| Salad, New England. Ill. | 275 |

| Salmon à la Creole | 275 |

| Sauce, Aigre-Doux | 280 |

| Sausages, Potato-and-Peanut | 273 |

| Steak, Skirt, with Raisin Sauce | 281 |

| Stuffing for Roast Turkey | 274 |

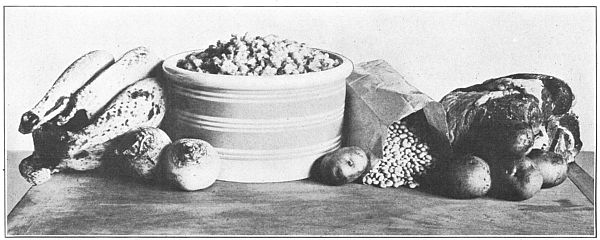

| Succotash, Plymouth. Ill. | 275 |

| Tart, Cranberry, with Cranberry Filling. Ill. | 279 |

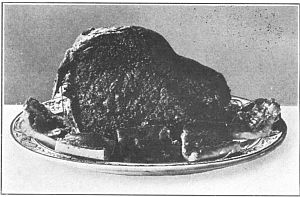

| Turkey, Roast. Ill. | 274 |

| Cake Baking, Temperature for | 298 |

| Chicken, To Roast | 295 |

| Corn and Potatoes, To boil | 295 |

| Fish, To broil | 298 |

| Gingerbread, Soft | 298 |

| Ice Cream, Classes of | 300 |

| Icing, Caramel | 295 |

| Pie, Deep-Dish Apple | 298 |

| Pies, Lemon, Why Watery | 296 |

| Pimientoes, Canned | 300 |

| Pineapple, Spiced | 295 |

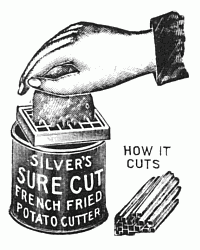

| Potatoes, Crisp Fried | 296 |

| Sauce, Cream | 298 |

| Sauce, Tartare | 296 |

| Table Service, Instructions on | 296 |

In addition to its fund of general information, this latest edition contains 2,117 recipes, all of which have been tested at Miss Farmer's Boston Cooking School, together with additional chapters on the Cold-Pack Method of Canning, on the Drying of Fruits and Vegetables, and on Food Values.

This volume also contains the correct proportions of food, tables of measurements and weights, time-tables for cooking, menus, hints to young housekeepers.

"'The Boston Cooking-School Cook Book' is one of the volumes to which good housewives pin their faith on account of its accuracy, its economy, its clear, concise teachings, and its vast number of new recipes."

| TABLE SERVICE | By Lucy G. Allen |

A clear, concise and yet comprehensive exposition of the waitress' duties. Detailed directions on the duties of the waitress, including care of dining room, and of the dishes, silver and brass, the removal of stains, directions for laying the table, etc. | |

| Fully illustrated. $1.75 net | |

COOKING FOR TWO | By Janet McKenzie Hill |

"'Cooking for Two' is exactly what it purports to be—a handbook for young housekeepers. The bride who reads this book need have no fear of making mistakes, either in ordering or cooking food supplies."—Woman's Home Companion. | |

| With 150 illustrations. $2.25 net | |

JUST PUBLISHED | |

| FISH COOKERY | By Evelene Spencer and John N. Cobb |

This new volume offers six hundred recipes for the preparation of fish, shellfish, and other aquatic animals, and there are recipes for fish broiled, baked, fried and boiled; for fish stews and chowders, purées and broths and soup stocks; for fish pickled and spiced, preserved and potted, made into fricassées, curries, chiopinos, fritters and croquettes; served in pies, in salads, scalloped, and in made-over dishes. In fact, every thinkable way of serving fish is herein described. | |

| $2.00 net | |

THE BOSTON COOKING-SCHOOL MAGAZINE COMPANY presents the following as a list of representative works on household economies. Any of the books will be sent postpaid upon receipt of price.

Special rates made to schools, clubs and persons wishing a number of books. Write for quotation on the list of books you wish. We carry a very large stock of these books. One order to us saves effort and express charges. Prices subject to change without notice.

| A Guide to Laundry Work. Chambers. | $1.00 |

| Allen, The, Treatment of Diabetes. Hill and Eckman | 1.75 |

| American Cook Book. Mrs. J. M. Hill | 1.50 |

| American Meat Cutting Charts. Beef, veal, pork, lamb—4 charts, mounted on cloth and rollers | 10.00 |

| American Salad Book. M. DeLoup | 1.50 |

| Around the World Cook Book. Barroll | 2.50 |

| Art and Economy in Home Decorations. Priestman | 1.50 |

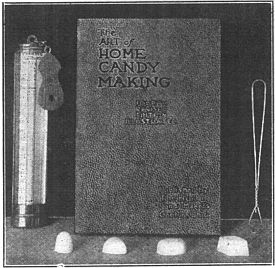

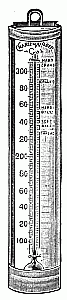

| Art of Home Candy-Making (with thermometer, dipping wire, etc.) | 3.75 |

| Art of Right Living. Richards | .50 |

| Bacteria, Yeasts and Molds in the Home. H. W. Conn | 1.48 |

| Bee Brand Manual of Cookery | .75 |

| Better Meals for Less Money. Greene | 1.35 |

| Blue Grass Cook Book. Fox | 2.00 |

| Book of Entrées. Mrs Janet M. Hill | 2.00 |

| Boston Cook Book. Mary J. Lincoln | 2.25 |

| Boston Cooking-School Cook Book. Fannie M. Farmer | 2.50 |

| Bread and Bread-Making. Mrs. Rorer | .75 |

| Breakfasts, Luncheons and Dinners. Chambers | 1.25 |

| Bright Ideas for Entertaining. Linscott | .90 |

| Business, The, of the Household. Taber | 2.50 |

| Cakes, Icings and Fillings. Mrs. Rorer | 1.00 |

| Cakes, Pastry and Dessert Dishes. Janet M. Hill | 2.00 |

| Candies and Bonbons. Neil | 1.50 |

| Candy Cook Book. Alice Bradley | 1.75 |

| Canning and Preserving. Mrs. Rorer | 1.00 |

| Canning, Preserving and Jelly Making. Hill | 1.75 |

| Canning, Preserving and Pickling. Marion H. Neil | 1.50 |

| Care and Feeding of Children. L. E. Holt, M.D. | 1.25 |

| Catering for Special Occasions. Farmer | 1.50 |

| Century Cook Book. Mary Ronald | 3.00 |

| Chafing-Dish Possibilities. Farmer | 1.50 |

| Chemistry in Daily Life. Lassar-Cohn | 2.25 |

| Chemistry of Cookery. W. Mattieu Williams | 2.25 |

| Chemistry of Cooking and Cleaning. Richards and Elliot | 1.00 |

| Chemistry of Familiar Things. Sadtler | 2.00 |

| Chemistry of Food and Nutrition. Sherman | 2.10 |

| Cleaning and Renovating. E. G. Osman | 1.20 |

| Clothing for Women. L. I. Baldt | 2.50 |

| Cook Book for Nurses. Sarah C. Hill | .90 |

| Cooking for Two. Mrs. Janet M. Hill | 2.25 |

| Cost of Cleanness. Richards | 1.00 |

| Cost of Food. Richards | 1.00 |

| Cost of Living. Richards | 1.00 |

| Cost of Shelter. Richards | 1.00 |

| Course in Household Arts. Duff | 1.30 |

| Dainties. Mrs. Rorer | 1.00 |

| Diet for the Sick. Mrs. Rorer | 2.00 |

| Diet in Relation to Age and Activity. Thompson | 1.00 |

| Dishes and Beverages of the Old South. McCulloch-Williams | 1.50 |

| Domestic Art in Women's Education. Cooley | 1.50 |

| Domestic Science in Elementary Schools. Wilson | 1.20 |

| Domestic Service. Lucy M. Salmon | 2.25 |

| Dust and Its Dangers. Pruden | 1.25 |

| Easy Entertaining. Benton | 1.50 |

| Economical Cookery. Marion Harris Neil | 2.00 |

| Elementary Home Economics. Matthews | 1.40 |

| Elements of the Theory and Practice of Cookery. Williams and Fisher | 1.40 |

| Encyclopaedia of Foods and Beverages. | 10.00 |

| Equipment for Teaching Domestic Science. Kinne | .80 |

| Etiquette of New York Today. Learned | 1.60 |

| Etiquette of Today. Ordway | 1.25 |

| European and American Cuisine. Lemcke | 4.00 |

| Every Day Menu Book. Mrs. Rorer | 1.50 |

| Every Woman's Canning Book. Hughes | .90 |

| Expert Waitress. A. F. Springsteed | 1.35 |

| Feeding the Family. Rose | 2.40 |

| Fireless Cook Book. | 1.75 |

| First Principles of Nursing. Anne R. Manning | 1.25 |

| Fish Cookery. Spencer and Cobb | 2.00 |

| Food and Cookery for the Sick and Convalescent. Fannie M. Farmer | 2.50 |

| Food and Feeding. Sir Henry Thompson | 2.00 |

| Food and Flavor. Finck | 3.00 |

| Foods and Household Management. Kinne and Cooley | 1.40 |

| Food and Nutrition. Bevier and Ushir | 1.00 |

| Food Products. Sherman | 2.40 |

| Food and Sanitation. Forester and Wigley | 1.40 |

| Food and the Principles of Dietetics. Hutchinson | 4.25 |

| Food for the Worker. Stern and Spitz. | 1.00 |

| Food for the Invalid and the Convalescent. Gibbs | .75 |

| Food Materials and Their Adulterations. Richards | 1.00 |

| Food Study. Wellman | 1.10 |

| Food Values. Locke | 2.00 |

| Foods and Their Adulterations. Wiley | 6.00 |

| Franco-American Cookery Book. Déliée | 5.00 |

| French Home Cooking. Low | 1.50 |

| Fuels of the Household. Marian White | .75 |

| [247]Furnishing a Modest Home. Daniels | 1.25 |

| Furnishing the Home of Good Taste. Throop | 4.50 |

| Garments for Girls. Schmit | 1.50 |

| Golden Rule Cook Book (600 Recipes for Meatless Dishes). Sharpe | 2.50 |

| Handbook of Home Economics. Flagg | 0.90 |

| Handbook of Hospitality for Town and Country. Florence H. Hall | 1.75 |

| Handbook of Invalid Cooking. Mary A. Boland | 2.50 |

| Handbook on Sanitation. G. M. Price, M.D. | 1.50 |

| Healthful Farm House, The. Dodd | .60 |

| Home and Community Hygiene. Broadhurst | 2.50 |

| Home Candy Making. Mrs. Rorer | .75 |

| Home Economics. Maria Parloa | 2.00 |

| Home Economics Movement. | .75 |

| Home Furnishing. Hunter | 2.50 |

| Home Nursing. Harrison | 1.50 |

| Home Problems from a New Standpoint | 1.00 |

| Home Science Cook Book. Anna Barrows and Mary J. Lincoln | 1.25 |

| Hot Weather Dishes. Mrs. Rorer | .75 |

| House Furnishing and Decoration. McClure and Eberlein | 2.50 |

| House Sanitation. Talbot | .80 |

| Housewifery. Balderston | 2.50 |

| Household Bacteriology. Buchanan | 2.75 |

| Household Economics. Helen Campbell | 1.75 |

| Household Engineering. Christine Frederick | 2.00 |

| Household Physics. Alfred M. Butler | 1.50 |

| Household Textiles. Gibbs | 1.40 |

| Housekeeper's Handy Book. Baxter | 2.00 |

| How to Cook in Casserole Dishes. Neil | 1.50 |

| How to Cook for the Sick and Convalescent. H. V. S. Sachse | 2.00 |

| How to Feed Children. Hogan | 1.25 |

| How to Use a Chafing Dish. Mrs. Rorer | .75 |

| Human Foods. Snyder | 2.00 |

| Ice Cream, Water Ices, etc. Rorer | 1.00 |

| I Go a Marketing. Sowle | 1.75 |

| Institution Recipes. Emma Smedley | 3.00 |

| Interior Decorations. Parsons | 5.00 |

| International Cook Book. Filippini | 2.50 |

| Key to Simple Cookery. Mrs. Rorer | 1.25 |

| King's, Caroline, Cook Book | 2.00 |

| Kitchen Companion. Parloa | 2.50 |

| Kitchenette Cookery. Anna M. East | 1.25 |

| Laboratory Handbook of Dietetics. Rose | 1.50 |

| Lessons in Cooking Through Preparation of Meals. | 2.00 |

| Lessons in Elementary Cooking. Mary C. Jones | 1.25 |

| Like Mother Used to Make. Herrick | 1.35 |

| Luncheons. Mary Ronald | 2.00 |

| A cook's picture book; 200 illustrations | |

| Made-over Dishes. Mrs. Rorer | .75 |

| Many Ways for Cooking Eggs. Mrs. Rorer | .75 |

| Marketing and Housework Manual. S. Agnes Donham | 2.00 |

| Mrs. Allen's Cook Book. Ida C. Bailey Allen | 2.00 |

| More Recipes for Fifty. Smith | 2.00 |

| My Best 250 Recipes. Mrs. Rorer | 1.00 |

| New Book of Cookery. A. Farmer | 2.50 |

| New Hostess of Today. Larned | 1.75 |

| New Salads. Mrs. Rorer | 1.00 |

| Nursing, Its Principles and Practice. Isabels and Robb | 2.00 |

| Nutrition of a Household. Brewster | 2.00 |

| Nutrition of Man. Chittenden | 4.50 |

| Philadelphia Cook Book. Mrs. Rorer | 1.50 |

| Planning and Furnishing the House. Quinn | 1.35 |

| Practical Cooking and Dinner Giving. Mrs. Mary F. Henderson | 1.75 |

| Practical Cooking and Serving. Mrs. Janet M. Hill | 3.00 |

| Practical Dietetics. Gilman Thompson | 8.00 |

| Practical Dietetics with Reference to Diet in Disease. Patte | 2.25 |

| Practical Food Economy. Alice Gitchell Kirk | 1.35 |

| Practical Homemaking. Kittredge | 1.00 |

| Practical Points in Nursing. Emily A. M. Stoney | 2.00 |

| Principles of Chemistry Applied to the Household. Rowley and Farrell | 1.50 |

| Principles of Food Preparation. Mary D. Chambers | 1.25 |

| Principles of Human Nutrition. Jordan | 2.00 |

| Recipes and Menus for Fifty. Frances Lowe Smith | 2.00 |

| Rorer's (Mrs.) New Cook Book. | 2.50 |

| Salads, Sandwiches, and Chafing Dish Dainties. Mrs. Janet M. Hill | 2.00 |

| Sandwiches. Mrs. Rorer | .75 |

| Sanitation in Daily Life. Richards | .60 |

| School Feeding. Bryant | 1.75 |

| Selection and Preparation of Food. Brevier and Meter | .75 |

| Shelter and Clothing. Kinne and Cooley | 1.40 |

| Source, Chemistry and Use of Food Products. Bailey | 2.00 |

| Spending the Family Income. Donham | 1.75 |

| Story of Germ Life. H. W. Conn | 1.00 |

| Successful Canning. Powell | 2.50 |

| Sunday Night Suppers. Herrick | 1.35 |

| Table Service. Allen | 1.75 |

| Textiles. Woolman and McGowan | 2.60 |

| The Chinese Cook Book. Shin Wong Chan | 1.50 |

| The House in Good Taste. Elsie de Wolfe | 4.00 |

| The Housekeeper's Apple Book. L. G. Mackay | 1.25 |

| The New Housekeeping. Christine Frederick | 1.90 |

| The Party Book. Fales and Northend | 3.00 |

| The St. Francis Cook Book. | 5.00 |

| The Story of Textiles | 5.00 |

| The Up-to-Date Waitress. Mrs. Janet M. Hill | 1.75 |

| The Woman Who Spends. Bertha J. Richardson | 1.00 |

| Till the Doctor Comes and How to Help Him. | 1.00 |

| True Food Values. Birge | 1.25 |

| Vegetable Cookery and Meat Substitutes. Mrs. Rorer | 1.50 |

| Women and Economics. Charlotte Perkins Stetson | 1.50 |

FRUIT SUPRÊME

FRUIT SUPRÊME

Select choice, fresh fruit of all varieties obtainable. Slice, using care to remove all skins, stones, seeds, membranes, etc.; for example, each section of orange must be freed from the thin membranous skin in which it grows. Chill the prepared fruit, arrange in fruit cocktail glasses with maraschino syrup. A maraschino cherry is placed on the very top of each service.

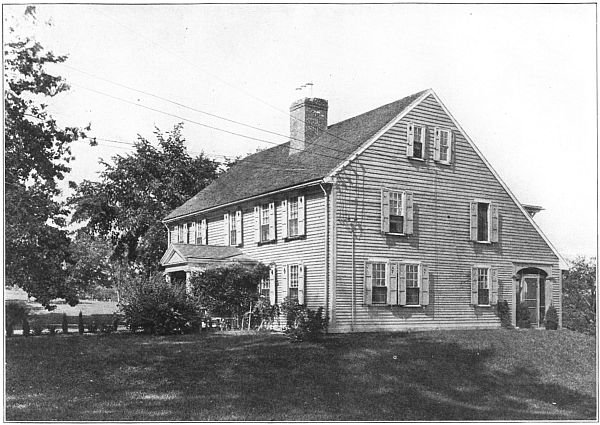

WOODEN SHUTTERS, ORNAMENTED, ARE SUITABLE FOR REMODELLED HOUSES

WOODEN SHUTTERS, ORNAMENTED, ARE SUITABLE FOR REMODELLED HOUSES

Through the glamour of the Colonial we are forced to acknowledge the classic charm shown in late seventeenth and early eighteenth century window designs. Developed, as they were, by American carpenters who were stimulated by remembrance of their early impressions of English architecture received in the mother land, there is no precise or spiritless copy of English details; rather there is expressed a vitality that has been brought out by earnest effort to reproduce the spirit desired. Undoubtedly the lasting success of early American craftsmanship has been due to the perfect treatment of proportions, as related one to the other. That these are not imitations is proved by an occasional clumsiness which would be impossible, if they were exact copies of their more highly refined English prototypes.

The grasp of the builder's mind is vividly revealed in the construction of these windows, for while blunders are often made, yet successes are much more frequent. They are evolved from remembered motives that have been unified and balanced, that they might accord with the exterior and be knitted successfully into the interior trim. Some of these windows still grace seventeenth century houses, and are found not only on old southern plantations, but all through New England, more especially along the sea coast. True products are they of Colonial craftsmanship, brought into existence by skilled artisans, who have performed their work so perfectly that today they are found unimpaired, striking a dominant note in accord with the architectural feeling of the period.

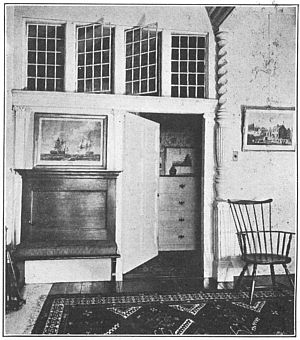

GROUP WINDOWS ON STAIRWAY

GROUP WINDOWS ON STAIRWAY

There is no question but that windows such as these lend character to any house, provided, of course, that they coincide with the period. Doubtless the designing of modified Colonial houses is responsible, in part, for the present-day revival of interest, not solely in windows of the Colonial period, but also in that which immediately preceded and followed it.

The first ornamental windows were of the casement type, copied from English cottage homes. Like those, they opened outward, and were designed with small panes, either diamond or square shaped. As they were in use long before glass was manufactured in this country, the Colonists were forced to import them direct[252] from England. Many were sent ready to be inserted, with panes already leaded in place. Proof of this is afforded by examples still in existence. These often show strange patches or cutting. The arrangement of casements varies from single windows to groups of two or three, and they were occasionally supplemented by fixed transoms. Surely no phase of window architecture stands out more conspicuously in the evolution of our early designs than the casement with its tiny panes, ornamented with handwrought iron strap-hinges which either flared into arrow heads, rounded into knobs, or lengthened into points. That they were very popular is shown from the fact that they withstood the changes of fashion for over a century, not being abolished until about the year 1700.

Little drapery is needed in casement windows where they are divided by mullions. The English draw curtain is admirable for this purpose. It can be made of casement cloth with narrow side curtains and valance of bright material. A charming combination was worked out in a summer cottage. The glass curtains were of black and white voile with tiny figures introduced. This was trimmed with a narrow black and white fringe, while the overdrapery had a black background patterned with old rose.

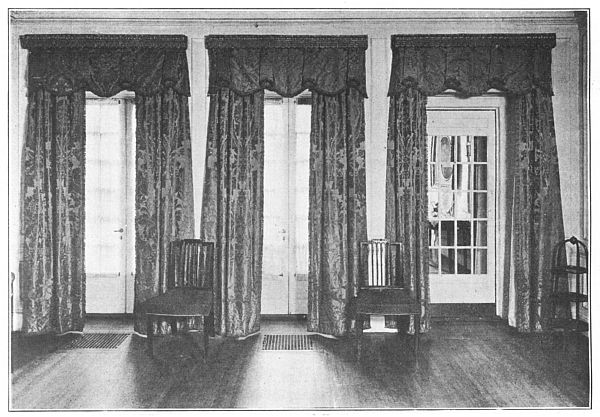

GROUPED WINDOWS WITH SQUARE PANES, LACE GLASS CURTAINS AND CRETONNE OVER CURTAINS

GROUPED WINDOWS WITH SQUARE PANES, LACE GLASS CURTAINS AND CRETONNE OVER CURTAINS

In the field of architectural progress, more especially during the last few years, there have arisen vast possibilities for the development of odd windows. These, if properly placed, showing correct grouping, are artistic, not only from the outside, but from the inside as well. The artistic woman, realizing the value of color, will fill a bright china bowl with glowing blossoms and place it in the center of a wide window sill, where the[253] sun, playing across them, will carry their cheerful color throughout the room. She also trains vines to meander over the window pane, working out a delicate tracery that is most effective, suspending baskets of ferns from the upper casement, that she may break the length of her Colonial window. Thus through many artifices she causes her simple room to bloom and blossom like a rose.

FOR FRENCH DOORS, USE MUSLIN WITH SILK-LINED OVERHANG

FOR FRENCH DOORS, USE MUSLIN WITH SILK-LINED OVERHANG

The progress made in window architecture is more apparent as we study the early types. Then small attention was paid to details, the windows placed with little thought of artistic grouping. Their only object to light the room, often they stood like soldiers on parade, in a straight row, lining the front of the house.

Out of the past has come a vast array of period windows, each one of which is of interest. They display an unmistakable relationship to one another, for while we acknowledge that they differ in detail and ornamentation, yet do they invariably show in their conception some underlying unity. There is no more fascinating study than to take each one separately and carefully analyze its every detail, for thus only can we recognize and appreciate the links which connect them with the early American types.

We happen upon them not only in the modified Colonial structures, but in houses in every period of architecture. It may be only a fragment, possibly a choice bit of carving; or it may be a window composed in the old-fashioned manner of from nine to thirty panes, introduced in Colonial days for the sake of avoiding the glass tax levied upon them if over a certain size. A charming example of a reproduction of one of these thirty-paned windows may be seen in a rough plaster house built in Salem, after the great fire. The suggestion was taken from an old historic house in a fine state of preservation in Boxford, Mass.

The first American homes derived their plans and their finish from medieval English tradition. They were forced to utilize such materials as they were able to obtain, and step by step they bettered[254] the construction and ornamentation of their homes. As increasing means and added material allowed, they planned and executed more elaborately, not only in size and finish, but in the adding of window casings, caps, and shutters.

The acme of Colonial architecture was reached with the development of the large square houses with exquisitely designed entrances and porticos. These often showed recessed and arched windows, also those of the Palladian type. At the Lindens, Danvers, Mass., a memory-haunted mansion, may be seen one of the finest examples of these recessed windows. This famous dwelling, the work of an English architect, who built it in about 1770, is linked with American history through its use by General Gage as his headquarters during the Revolution.

The recessed windows that are found here reveal delicate mouldings in the classic bead and filet design, and are surmounted by an elaborate moulded cornice, which lends great dignity to the room. This is supported by delicate pilasters and balanced by the swelling base shown below the window seats. Such a window as this is no mere incident, or cut in the wall; on the contrary, it is structural treatment of woodwork. Another feature of pronounced interest may be noted on the stair landing, where a charming Palladian window overlooks the old-fashioned box-bordered garden that has been laid out at the rear.

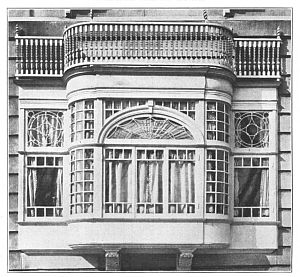

We have dwelt, perhaps, too much on the old Colonial types, neglecting those of the present day, but it has been through a feeling that with an intimate knowledge of their designs we shall be better able to appreciate the products of our own age, whose creators drew their inspiration from the past. A modern treatment of windows appears in our illustration.

75 BEACON STREET, BOSTON

75 BEACON STREET, BOSTON

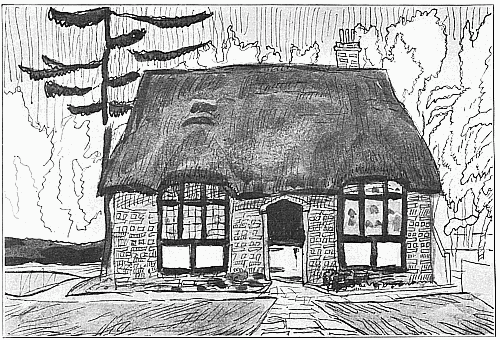

THATCHED-STYLE COTTAGE FOR AMERICAN SUBURBS

THATCHED-STYLE COTTAGE FOR AMERICAN SUBURBS

If, some fine day, all housewives awoke to the fact that most of the trouble in the world originates in the kitchen, there would shortly be a little more interest in kitchen problems and not so much distaste for and neglect of this important part of the house.

Of course, women will cry out that we have never in our lives been so intent on just that one subject, kitchens, as we are today.

I admit that there is a good deal of talk going on which might lead one to believe that vacuum cleaners and electric-washing machines, etc., are to bring about the millennium for housekeepers; and there is also a good work going forward to make of housework a real profession.

But, until in the average home there comes the feeling that the kitchen—the room itself—is just as much an expression of the family life and aims and ideals as the living room or any other room, we shall be only beating about the bush in our endeavor to find a remedy for some of our perplexing troubles.

Nowadays, women who are doing much work out in the big world—the so-called "enfranchised" women—are many of them proving that they find housework no detriment to their careers and some even admit that they enjoy it.

But so far most of them have standardized their work and systematized it, with the mere idea of doing what they have to do "efficiently" and well, with the least expenditure of time and energy. And they have more than succeeded in proving the "drudgery" plea unfounded.

Now, however, we need something more. We need to make housework attractive; in other words, to put charm in the kitchen.

There is one very simple way of doing[256] this, that is to make kitchens good to look at, and inviting as a place to stay and work.

For the professional, scientifically inclined houseworker, the most beautiful kitchen may be the white porcelain one, with cold, snowy cleanliness suggesting sterilized utensils and carefully measured food calories.

But to the woman whose cooking and dishwashing are just more or less pleasant incidents in a pleasant round of home and social duties, the kitchen must suggest another kind of beauty—not necessarily a beauty which harbors germs, nor makes the work less conveniently done, but a beauty of kindly associations with furniture and arrangements.

Who could grow fond of a white-tiled floor or a porcelain sink as they exist in so many modern kitchens! And as for the bulgy and top-heavy cook stoves, badly proportioned refrigerators, and kitchen cabinets—well, we should have to like cooking very well indeed before we could feel any pleasure in the mere presence of these necessary but unnecessarily ugly accompaniments to our work.

We have come to think of cleanliness as not only next to godliness, but as something which takes the place of beauty—is beauty.

This attitude is laziness on our part, for we need sacrifice nothing to utility and convenience, yet may still contrive our kitchen furniture so that it, also, pleases the senses. With a little conscientious reflection on the subject we may make kitchens which have all the charm of the old, combined with all the convenience of the new; and woman will have found a place to reconcile her old and new selves, the housewife and the suffragist, the mother-by-the-fireside and the participator in public affairs. The family will have found a new-old place of reunion—the kitchen!

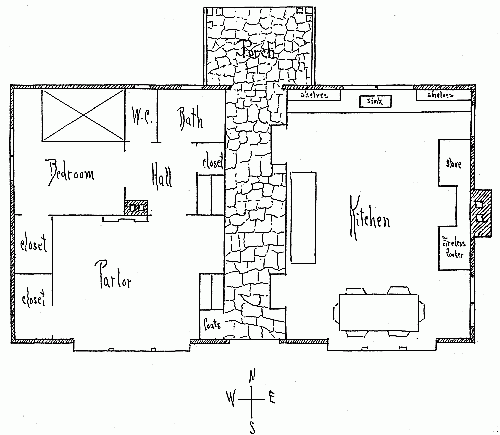

Granted then that our tiny house has a kitchen-with-charm, and an "other room," the rest of the available space may be divided into the requisite number of bed and living rooms, according to the needs of the family.

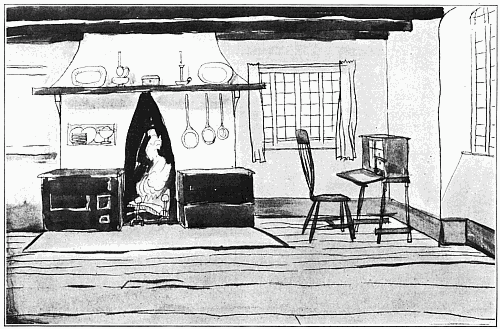

KITCHEN FOR THATCHED-STYLE COTTAGE

KITCHEN FOR THATCHED-STYLE COTTAGE

There is only one other very important thing to look out for; that is the matter of closets. There is no rule for the[257] number of closets which will make the tiny house livable, but I should say, the more the merrier. If there is ever question of sacrificing a small room and gaining a large closet, by all means do it, for absolute neatness is the saving grace of small quarters, and storage places are essential, if one does not wish to live in a vortex of yesterday's and tomorrow's affairs with no room to concentrate on the present.

FIRST-FLOOR PLAN OF THATCHED COTTAGE

FIRST-FLOOR PLAN OF THATCHED COTTAGE

Inside and outside the tiny house must conform to one law—elimination of non-essentials; and the person who has a clear idea of his individual needs and has also the strength of will to limit his needs to his circumstances, will find in his tiny house a satisfaction more than compensating for any sacrifices he may have made.

No one doubts that it is a sacrifice to give up a lesser pleasure even to gain the "summum bonum" and that it does take will power to keep oneself from weakly saying in the face of temptation, "Oh, well! what does it matter! My little house would perhaps be better without that, but I have grown accustomed to it, let it stay!"

Oh! the waste lands which lie beneath the sun trying to call themselves gardens! Oh! the pitiful little plots, unfenced, unused, entirely misunderstood by people who stick houses in the middle of them and call them "gardens"!

No amount of good grass seed, or expensive planting, or well-cared-for flowers and lawns will ever make the average suburban lot anything but a "lot," and most of them might as well, or better, be rough, uncultivated fields for all the relation they bear to the houses upon them or the use they were intended for.

"Huh!" exclaimed Jennie, "there comes Aunt Rachel! Wonder what she wants now? Last time it was—no, it wasn't—that was the time when Jimmie Upson and his wife were here. How scandalized Aunt Rachel looked! Said I'd ruin my husband, and a lot of such tommyrot. As though Jimmie and I couldn't afford a spread now and then! I didn't, and I won't, tell Aunt Rachel that it was a special party and a special occasion. Of course, I know Jimmie isn't a millionaire, but—it's none of Aunt Rachel's business, so there!" she finished defiantly.

Aunt Rachel plodded blissfully up the walk. "Jennie'll be glad to see me, I know," she mused. "She's high-headed, but she knows a good thing when she sees it, and I help her a lot."

Jennie received her aunt with cordiality, but not effusiveness. To be discourteous was something she could not be. Besides, she liked Aunt Rachel and pitied her idiosyncrasies. "Why can't she be as nice when she goes to people's houses as she is when she is at home?" she mused. "I love to go there, and everything is just perfect, but the minute she steps outside the door—well, we all know Aunt Rachel! And she doesn't go home early either. Jimmie'll be furious. She always calls him 'James' and asks after his health and—and everything. I do so want him to like her, but I'm afraid he never will. I do wish I could get her interested in something. I have it!" she exclaimed triumphantly. "The very thing!"

Aunt Rachel looked up in surprise. "What's the matter, Jennie?" she inquired.

"Oh, nothing much, Auntie! I was just thinking aloud."

"Don't!" said Aunt Rachel. "It's a bad habit, Jennie—though I do do it myself, sometimes."

"Sometimes!" Jennie turned away to hide her smile. Why, Aunt Rachel made a business of talking aloud!

As luck would have it, the dinner went off to Aunt Rachel's satisfaction. It was good, but conservative.

"Jennie is learning," thought the old lady to herself. "After I've been here a few times more, she'll get along all right."

Aunt Rachel hadn't noticed that every idea Jennie has used was, strictly, either Jennie's own or her mother's.

"How long does your aunt expect to stay?" asked Jimmie, casually, while Jennie was clearing the table. Aunt Rachel was in the kitchen. She prided herself on never being "a burden on any one." Doubtless, some of her friends would have preferred that she be. Most of us have a skeleton we do not wish to keep on exhibition.

"Oh, I don't know, maybe a week or two," said Jennie, mischievously. "She hasn't told me yet."

"Oh!" replied Jimmie, in a disappointed voice. "Business down town"? "Dinner at the Club"? No, he couldn't keep that up indefinitely. Besides, what did a man want of a home, if he wasn't going to live in it? Covertly, Jennie watched him. She knew every expression of his face. It amused her, but she was sorry, too. "Jimmie wants awfully to flunk—and dassent," was her mental comment.

"Anything on for this evening, Jimmie?" inquired Jennie, sweetly, too sweetly, Jimmie thought. He had heard those dulcet tones before.

"Yes—no!" stammered Jimmie. How he wished he had! However, as Jennie said no more, he dismissed the subject[259] from his mind. She probably didn't really mean anything, anyway.

When James Atherton reached home that evening, he found the house lighted from top to bottom. Beautifully dressed women were everywhere, and in their midst—Aunt Rachel, at her best!

"Ladies," she exclaimed, and Jimmie paused to listen, "I am honored—more so than you can guess—at the distinction conferred upon me. This afternoon you have seen fit to make me one of your leaders in a most important movement for civic betterment—an honor never before accorded a woman in this city—and I need not assure you that you shall not regret your choice. As a member of the Civic Betterment Committee of Loudon, I shall do my duty." ("I bet she will!" commented Jimmie, sotto voce.) "Again I thank you!" went on Aunt Rachel. "There's a work for you and for me now to do, and—" she paused impressively, "we will do it." ("I'll bet on you every time, Auntie," commented Jimmie to himself.)

"Jimmie Atherton, what in the world are you doing?" whispered an exasperated voice. "Hurry, Jimmie, hurry—do!" urged Jennie. "Dinner is almost ready to serve, and you haven't even made the first move to dress. Hurry, Jimmie, please!" And Jimmie did. He fairly sprinted into his clothes, appearing presently fully clad and good to look upon.

"Bet you a nickel Jennie couldn't have done that," he reflected, complacently. "Women never can get a move on them, where clothes are concerned."

That was the best evening Aunt Rachel had ever spent. She was the center of attraction; she had found a mission—not a desultory one, but one far-reaching in scope, so it seemed to her; and like a war-horse, she was after the charge.

Jennie's plans went through without a hitch. Aunt Rachel became, not only a member of the Committee on Civic Betterment, but, as well, its head and, in due season, mayor of the little city itself. Under her active management, Loudon became noted as a model city of its size, one good to look upon and good to live in. Crime fled, or scurried to cover, and Aunt Rachel blossomed like a rose. One day when Jimmie came home something seemed to please him greatly.

"What do you think, Jennie," he said, "Aunt Rachel is going to be married! Yes, she is! I've got it on the best of authority—the groom himself."

"Who?" gasped Jennie. "Why, Jimmie, she just HATES men! She's always said they were only a necessary evil."

"Yes, I know," smiled Jimmie, "that's what she used to say, but she'd never met Jacob Crowder then."

"Jacob Crowder!" exclaimed Jennie. "Why, Jimmie, he's as rich as Croesus, and he's always hated women as much as Aunt Rachel has hated men!"

"Yes," said Jimmie, "but that was before he met Aunt Rachel. He has been her righthand man for some time now, and they've seemed to hit it off pretty well. Guess they'll get along all right in double harness."

"When the girls and I steered Aunt Rachel into politics," said Jennie, "little we thought where it would all end. I'm glad, glad, though! Aunt Rachel is really splendid, but I've always thought she was suffering from something. Now I know what—it's ingrowing ambition. She will have all she can do now to take care of her own home and we won't see her so often."

"Oh, ho! So that's it?" smiled Jimmie. "Well, you girls, as has happened to many another would-be plotter before now, have found things have gotten rather out of your hands, haven't you?"

Jennie shrugged her shoulders.

"We can have the wedding here, can't we, Jimmie?" she asked, somewhat wistfully.

Jimmie wondered if she had heard him. Perhaps—and then again, perhaps not.

"I don't see where we come in on it," he remarked. "It's a church affair, you know."[260]

"Oh!" said Jennie. "But there'll be a reception, of course, and if she'll let us have it here, I'll have every one of us girls she has helped so much in the past."

Jimmie stared. "Consistency—" he muttered.

"What's that you said, Jimmie? Are you ill?" inquired Jennie, anxiously.

"No!" replied Jimmie, "it's you women! I can't understand you at all!"

"You're not supposed to, Jimmie, dear," answered Jennie sweetly.

I never thought I should come to like cats. But I have. Perhaps it is because, as my Aunt Amanda used to say, we change every seven years, sort of start over again, as it were; and find we have new thoughts, different ideas, unexpected tastes, strange attractions, and shifting doubts. Or, it may be, we merely come to a new milestone from which, looking back, we are able to regard our own personality from a hitherto unknown angle. We discover ourselves anew, and delight in the experiment.

Or, it may all be, as my husband stolidly affirms, just the logical result of meeting Sir Christopher Columbus, a carnivorous quadruped of the family Felidæ, much domesticated, in this case, white with markings as black and shiny as a crow's wing, so named because he voyaged about our village, not in search of a new world, but in search of a new home. He came to us. It is flattering to be chosen. He stayed. But who could resist Sir Christopher?

My husband and my Aunt Amanda may both be right. I strongly suspect they are. I also strongly suspect that Sir Christopher himself has much to do with my change of mental attitude: He is well-mannered, good to look upon, quite adorable, independent and patient. (Indeed, if people were half as patient as my cat this would be a different world to live in.) More: He has taught me many things, he talks without making too much noise; in fact, I have read whole sermons in his soft purrings. And I verily believe that many people might learn much from the family cat, except for the fact that we humans are such poor translators. We know only our own language. More's the pity.

Had I known Sir Christopher as a kitten, doubtless he might have added still more to my education. But I did not. He was quite full grown when I first laid my eyes upon him. He was sitting in the sun, on top of a rail fence, blinking at me consideringly. The fence skirted a little trail that led from my back yard down to Calapooia Creek. It seemed trying to push back a fringe of scrubby underbrush which ran down a hillside; a fringe which was, in truth, but a feeler from the great forest of Douglas fir which one saw marching, file upon file, row upon row, back and back to the snows of the high Cascades.

And the white of Sir Christopher's vest and snowy gauntlets was just as gleamingly clean as the icy frosting over the hills. Sir Christopher, even a cat, believed firmly in sartorial pulchritude. I admired him for that, even from the first glance; and, afterward, I put me up three new mirrors: I did not mean to be outdone by my cat, I intended to look tidy every minute, and there is nothing like mirrors to tell the truth. Credit for the initial impulse, however, belongs to Christopher C.

But that first morning, I merely glanced at him, sitting so comfortably on the top rail of the fence, blinking in the sun.[261]

"Somebody's cat," said I, and went on down to the creek to see if Curlylocks had tumbled in.

Coming back, the cat was still there. Doubtless he had taken a nap between times. But he might have been carved of stone, so still he lay, till my youngest, tugging at my hand, coaxed:

"Kitty—kitty—kitty. Muvver, see my 'ittle kitty?"

And I declare, if Sir Christopher (my husband and ten-year-old Ted named him that very evening) didn't look at me and wink. Then he jumped down and followed, very dignified, very discreet.

I attempted to shoo him back. But he wouldn't shoo. He merely stopped and seemed to consider matters. Or serenely remained far enough off to "play safe."

Meanwhile, my youngest continued to reiterate: "Kitty—kitty—kitty! My 'ittle kitty!"

"No, Curlylocks," said I, "it isn't your little kitty. It is somebody's cat."

Which merely shows that I knew not whereof I spoke. Sir Christopher proceeded to teach me.

Of course, at first I thought his stay with us was merely a temporary matter; like some folk, he had decided to go on a visit and stay over night. But when Sir Christopher continued to tarry, I enquired, I looked about, I advertised—and I assured the children that some one, somewhere, must surely be mourning the loss of a precious pet; some one, sometime, would come to claim him.

But no one came.

Days slid away, weeks slipped into months, winter walked our way, and spring, and summer again. Sir Christopher C. had deliberately adopted us, for he made no move toward finding another abiding place. He was no longer Somebody's cat, he was our cat; for, indeed, is not possession nine points of the law?

Then one day when heat shimmered over the valley, when the dandelions had seeded and the thistles had bloomed, when the corn stood heavy and the cricket tuned his evening fiddle, when spots in the lawn turned brown, where the sprinkler missed, when the baby waked and fretted, and swearing, sweating men turned to the west and wondered what had held up the sea breeze—Sir Christopher missed his supper. He vanished as completely as if he had been kidnapped by the Air Patrol. Three weeks went by and we gave him up for lost, although the children still prowled about looking over strange premises, peeping through back gates, trailing down unaccustomed lanes and along Calapooia Creek, for "We might find him," they insisted. Truly, "Hope springs eternal."

"Perhaps, he has gone back where he came from," said Daddy. "Perhaps, he has grown tired of us."

But My Man's voice was a little too matter-of-factly gruff—indeed, he had grown very fond of Sir Christopher—and as for the children, they would accept no such explanation.

It was Curlylocks who found Sir Christopher—or did Sir Chris find Curlylocks? Anyway, they came walking through the gate, my youngest declaiming, "Kitty—kitty—kitty! My 'ittle kitty!"

And since that time, every summer, Sir Christopher takes a vacation. He comes back so sleek and proud and happy that he can hardly contain himself. He rubs against each of us in turn, purring the most satisfied purr—if we could but fully understand the dialect he speaks!—as if he would impart to us something truly important.

"I declare," said Daddy, one day, "I believe that cat goes up in the hills and hunts."

"Camps out and has a good time," added daughter.

"And fishes," suggested Ted. "Cats do catch fish. Sometimes. I've read about it."

Daddy nodded. "Seems to agree with him, whatever he does."[262]

"Vacations agree with anybody," asserted my oldest. And then, "I don't see why we can't go along with Sir Chris. At least we might go the same time he does."

"Mother, couldn't we?"—it was a question that gathered weight and momentum like a snowball rolling down hill, for I had always insisted that, with a big family like mine, I could never bother to go camping. I wanted to be where things were handy: running water from a faucet, bathtubs and gas and linoleum, a smoothly cut lawn and a morning postman. Go camping with a family like mine? Never.

But the thought once set going would not down. Perhaps, after all, Sir Christopher was right and I was wrong. For people did go camping, most people, even groups to the number of nine (the right count for our family), and they seemed to enjoy it. They fought with mosquitoes, and fell into creeks; they were blotched with poison oak, black from exposure, lame from undue exercise, and looked worse than vagrant gipsies—but they came home happy. Even those who spent days in bed to rest up from their rest (I have known such) seemed happy. And every one sighs and says, "We had such a good time! We're planning to go back again next summer."

So at last I gave up—or gave in. We went to the mountains, following up the trail along Calapooia Creek; we camped and hunted and fished to the hearts' content. We learned to cook hotcakes out-of-doors, and how to make sourdough biscuit, and to frizzle bacon before a bonfire, and to bake ham in a bread pan, such as our mothers fitted five loaves of bread in; we learned to love hash, and like potatoes boiled in their jackets, and coffee with the cream left out. We went three miles to borrow a match; we divided salt with the stranger who had forgotten his; we learned that fish is good on other days than Friday and that trout crisps beautifully in bacon grease; we found eleventeen uses for empty lard pails and discovered the difference between an owl and a tree toad. We gained a speaking acquaintance with the Great Dipper, and learned where to look for the north star, why fires must be put out and what chipmunks do for a living. We learned—

Last night we came home.

"Now, mother, aren't you really glad you went?" quizzed Daddy.

"Yes-s," said I, slowly, "I'm glad I went. It has been a new experience. I feel like I'd gained a degree at the State University."

My understanding mate merely chuckled—and went on unpacking the tinware. But Ted spoke up:

"Gee! Bet I make good in English III this year. Got all sorts of ideas for themes. This trip's been bully."

"We'll go again, won't we, Mother?" asked my oldest.

"I think we'll always go again," answered I—some sober thinking I was doing, as I folded away the blankets.

"Let me get supper"—it was Laura, my middle girl, speaking—"surely I can cook on gas, if I can over a campfire." And Laura had never wanted to cook! Strange tendencies develop when one lives out in the open a space of time.

But Curlylocks was undisturbed. "Kitty—kitty—kitty! My 'ittle kitty!" he reiterated. And truly, so my neighbor told me, Sir Christopher had beat us home by a scant twenty-four hours. He rubbed about us in turns, happily purring.

"He's telling us all what a good time he had," said I, understanding at last, "but he is adding, I think, that the best part of going away is getting home again."

"But if we didn't go we couldn't get home again," said Somebody.

And somebody's cat purred his approval. Perhaps, after all, he finds us a teachable family. Or perhaps he knows that once caught by the lure of the hills, once having tasted the tang of mountainous ozone, we will always go back—he has rare intuitions, has Sir Christopher. For, already, I find myself figuring to[263] fashion a detachable long handle for the frying pan: Yes, next time, we shall plan to conserve both fingers and face. Next time! That is the beauty of vacation days: We think of them when the frost comes, when the snow drifts deep, when the arbutus blooms again—and we plan, plan, plan! And are very happy—because of memory, and anticipation. We have opened barred windows, and widened our life's horizon. Does Sir Christopher guess? Wise old Sir Chris!

There were four of them—all girls employed in great offices. Alone, far away from their home towns and families, they were all suffering from attacks of too-much-boarding-house. Each was longing for a real, home-y place to live in. And out of that longing was born, in time, an idea, which developed, after much planning, figuring and price-getting, into a concrete plan and a course of action. They were good friends, of congenial tastes, and so they decided to "home-it" together.

Now this is nothing new, in itself. It was the thorough way they went about it that was not so common. They applied the rules of their business life, and studied their proposed path before they set foot in it. They looked over the field, weighed the problems, decided what they could do, and then arranged to put themselves on a sound financial basis from the start.

All had occupied separate rooms in sundry boarding houses. Each had experience in "meals in" and "meals out." Each could analyze fairly accurately her expenses for the preceding six months. After study, they decided that, without increasing their combined expense, they could have comfortable quarters of their own and more than meet all their needs. "Freedom, food, furniture, fixing and friends," said Margaret, "without the boarding house flavor."

They longed for a little house and garden of their own. But they were busy people, and this would mean extra hours of care and labor, more demands on their strength, and a longer travel distance—a load they felt they could not carry. So they sought an apartment.

The search was long but they found it. It was in a small structure, on a quiet street, and several flights up, without elevator. But, as Peggy said, "Elevators have not been in style in our boarding houses, and flights of stairs have—so what matters it?" The suite, when you arrived up there, was airy and comfortable. It provided two bedrooms, a cheery living room, a dining room and a kitchenette. Clarice remarked, "The 'ette' is so small we can save steps by being within hand's reach of everything, no matter where we stand."

The rent was less than the combined rental of their four old rooms. Heat and janitor service were provided without charge, but they were obliged to meet the expense of gas for the range and of electric lights.

They might have lived along happily in their new nest without a budget, and without specific agreements as to expense. But they were business girls. So they sat right down and decided every point, modifying each, under trial, to a workable proposition. Then they stuck to it and made it work.

There was the matter of furnishing. Each partner, while retaining personal title to her property, contributed to general use such articles of furniture she possessed as met apartment needs. From one, for example, came a comfortable[264] bed, from another, chairs and a reading lamp, from a third a lounge chair, and from the fourth her piano and couch. Of small rugs, sofa pillows, pictures and miscellaneous small furnishings there were sufficient to make possible a real selection.

Then the four determined on further absolute essentials to make the rooms homelike. There were needed comfortable single beds for each, dressing tables, bed linen, dining-room equipment, kitchen ware, a chair or two, and draperies. Their decisions were made in committee-of-the-whole, and nothing was done that could not meet with the willing consent of all.

To meet the first cost they each contributed fifty dollars from their small savings, and assessed themselves a dollar and a quarter per week thereafter. They then bought their equipment, paying part cash and arranging for the balance on time. And be sure it was fun getting it!

Then there was the question of meals. It was determined to prepare their breakfasts and dinners and to put up lunches. To allow a certain freedom, it was agreed that each should pack her own lunch, and that regular meals should be cooked and served, turn and turn about, each partner acting for a week. A second member washed the dishes and took general care of the apartment. Thus a girl's general program reduced to,

| First week | Cooking |

| Second week | Free |

| Third week | Dishes, etc. |

| Fourth week | Free |

| Fifth week | Cooking |

| Etc. | |

During an experimental period, the cost of provisions and ice was summed up weekly and paid by equal assessment. Later a fixed assessment of seven dollars, each, was agreed to, and proved sufficient. There were even slight surpluses to go into the mannikin jar on the living room mantel, which Clarice called the "Do Drop Inn", because it provided from its contents refreshment for those who dropped in of an evening.

Naturally there was a friendly rivalry, not only in making the most of the allotment, but in providing attractive meals and dainty special dishes. Clarice's stuffed tomatoes won deserved fame, and Margaret made a reputation on cheese soufflé. Peggy, too, was a wizard with the chafing dish.

Consideration was given the matter of special guests, either for meals, or for over-night. The couch in the living room provided emergency sleeping quarters. As for meals, separate fixed rates were set for breakfasts and for dinners. This was paid into the regular weekly provision fund by the girl who brought the guest, or by all four equally, if she were a "general" guest. The girl who brought a guest also "pitched in" and helped with the work.

Whenever the group went out for a meal, as they did now and then for a change, or for amusement, or recreation, each girl paid her own share at once.

Finally, there was the factor of laundry. After a little experimenting, household linen was worked out on an "average" basis, so that a regular amount could be assessed each week. Of course each girl met the expense of her own private laundry.

As a result of this planning, each member of the household found herself obligated to meet a weekly assessment containing the following items: Rent, furniture tax, household laundry, extras ($1.00) and personal laundry. Of these, the only item not positively fixed, as to amount, was the last. Each girl, naturally, paid all her strictly private expense, including clothes, and medical and dental service.

One of the number was chosen treasurer for a three-months' term, and was then, in turn, succeeded by another, so that each of the four served once a year. The treasurer received all assessments, gave the weekly allotment to the housewife, and paid other bills. Minor defi[265]ciencies were met from "surplus." Moreover, she kept accurate accounts.

Once settled comfortably in their quarters, with boarding-house memories receding into the background, it took but little time for a happy, home-y atmosphere to develop. Of course, with closer intimacy, there were temperamental adjustments, as always, but they came easily. The household machinery ran smoothly, almost from the first, because there was a machine, properly set up, operated and adjusted—rather than an uncertain makeshift.

"'Keep house?' I should say not!" answered Anne, who had journeyed out into the suburbs to "tell" her engagement to Burt Winchester to the home folks before she "announced" it. "I'm going to retire to the Kensington, or some nice apartment hotel, at the ripe old age of twenty-four. What'd you think, we're back in the dark ages, B. F.?"

"'B. F.'?" repeated Aunt Milly.

"Before Ford," said Anne, laughing. "Oh, it was the thing for you, Auntie, you couldn't have brought up your own big family in a city apartment, to say nothing of stretching your wings to cover Little Orphant Annie, besides, everybody kept house when you were married!"

"And now nobody does, except a few Ancient Mariners?" inquired Cousin Dan.

Anne blushed. "Of course it suits some people, now," she amended, hastily. "Perhaps it's all right to keep house, if you have a big family, or lots of money and can hire all the fussing done."

"You don't need to hire fussing, if you've a big family," said Aunt Milly, her eyes twinkling behind the gold-bowed spectacles. "You'll keep on with the drawing—illustrating?"

"Surely," answered Anne. "Burt will keep right on being a lawyer."

"I see," said George. "Well, Queen Anne, I suppose when we want to visit you we can hire a room in the same block, I mean, hotel. I thought, perhaps, having so far conformed to the habits of us Philistines as to take a husband, you might go the whole figure and take a house!"

"Please!" begged Anne. In that tone, it was a catchword dating back to nursery days which the elf-like Anne had shared with a whole brood of sturdy cousins, and meant, "Please stop fooling; I want to be taken seriously."

"I love to draw—but my people don't look alive, somehow," said little Milly, wistfully.

Cried Anne: "Keep trying, Milly; there is nothing so lovely as to have even a taste for some sort of creative work, and to develop it; to express your own personality in something tangible, and to be encouraged to do so. Do understand me, Auntie and the rest; it isn't that I want to shirk, but I do want to specialize on what I do best! I'll wash dishes if it's ever necessary, but why must I wish a whole pantry on myself when either Burt or I could pay our proportionate share of a hotel dish-washer, or butler, or whatever is needed?"

At the studio it was much easier.

"Some time in the early fall," Anne told her callers, who arrived by two's, three's and four's, as the news began to circulate among her friends.

"No, I won't keep this," with a jerk of her thumb towards the big, bare room which had been hers since she left Aunt Milly and the little home town. "There's a room at the top of the Kensington I can have, with a light as good as this, and[266] that settles the last problem. I'd hate to have to go outdoors for meals, when I'm working."

"Nan Gilbert!" exclaimed her dearest friend. "You have the best luck! You can do good work, and get good pay for it, and be happy all by yourself; and now you're going to be happier, with a husband who'll let you live your own life; you'll be absolutely free, not even a percolator to bother with, nothing to take your mind from your own creative work, free to express your own personality!"

"Mercy," said Anne, closing the door upon this last caller. "If I don't set the North River, at least, on fire, pretty soon, they'll all call me a slacker."

She hung her card, "Engaged," upon the door leading into the hall (some one had scrawled "Best Wishes" underneath the printed word), and proceeded to get her dinner in a thoughtful frame of mind. The tiny kitchenette boasted ice-box, fireless, and a modest collection of electric cooking appliances; in a half-hour Anne had evolved a cream soup, a bit of steak, nearly cubical in proportions, slice of graham bread, a salad of lettuce and tomato with skilfully tossed dressing, a muffin split ready to toast, with the jam and spreader for it, and coffee was dripping into the very latest model of coffee-pots. Anne had never neglected her country appetite, and was a living refutation of the idea that neatness and art may not dwell together. She moved quietly and with a speed which had nothing of haste; her mind was busy with a magazine cover for December, she believed she'd begin studying camels.

After dinner came Burt Winchester, a steady-voiced, olive-skinned young man, in pleasant contrast to Anne's vivacious fairness, and together they journeyed uptown and then west to the Kensington, for a final decision upon the one vacant apartment. The rooms were of fair size, they were all light, and the agent had at least half a yard of applicants upon a printed slip in his pocket.

Burt studied the apartment not at all, but his fiancée with quiet amusement. He was much in love with Anne, but he understood her better than she had yet discovered.

"I don't think we'll ever find anything better," she was saying to him. "Perhaps he'd have it redecorated for us, with a long lease—"

The agent coughed discreetly. "The leases are for one year, with privilege of renewal," he said to Burt. "It has just been redecorated; is there anything needed?"

"It would all be lovely, if one liked blue," murmured Anne. "Just the thing for some girl, but not for me, all that pale blue and silver, it doesn't look a bit like either of us, Burt. I had worked out the most stunning scheme, cream and black, with a touch of Kelly green—"

Another cough, somewhat louder, and accompanied by an undisguised look of sympathy for Burt. "The owner prefers to decide the decorations, Madame," said the agent. "Tastes differ so, you understand."

"Please hold the suite for me until tomorrow night," said Burt, decisively. "I suppose we'll take it; if not, I'll make it right with you."

"I should say, 'tastes differ,'" laughed Anne, tucking her arm into Burt's, as they began the long walk down-town. "Do you know, Aunt Milly and the girls thought, of course, we'd keep house, and Dan and George are going to pick out girls that will keep house, I saw it in their eyes. You—you're going to be satisfied, Burt?"

"I think so," answered Burt, judiciously, and then with a change of tone, "Nan, you precious goose, you've always told me you were not domestic."

"And you've always said you were no more domestic than I was," finished Anne, happily. She entirely missed the quizzical expression of the brown eyes above her. "Nuff said.—Are we going to Branton tomorrow, Burt, with the crowd? Can you take the day?"

Anne's "crowd," the half-dozen good[267] friends among the many acquaintances she had formed in the city, were invited for a day in the country. She and Burt now talked it over, agreeing to meet in time to take the nine-thirty train, with the others.

But at nine, next morning, Burt had not appeared at the studio; instead, Miss Gilbert had a telephone message that Mr. Winchester was delayed, but would call as soon as possible. It was unlike Burt, but Anne, sensibly, supposed that business had intervened, and, removing her hat, was glad to remember that she had not definitely accepted the invitation when it was given. The "crowd" were sure enough of each other and of themselves to appear casual: Burt and she could take a later train, and have just as warm a welcome.

At nine-thirty Burt appeared, explaining briefly, "Best I could do. There's a train in twenty minutes, we'll catch it if we hurry."

Anne hurried, which proved to be unnecessary, as the train seemed late in starting; during the trip there was little conversation, as Anne was tactful, and Burt preoccupied.

"Branton!" called the conductor, at least it sounded like Branton, Burt came out of his revery with a start, and Anne followed him down the aisle. They stood a moment upon the platform of the quiet little station and watched the train pull out; as they turned back into what seemed the principal street, Anne craned her neck to look around an inconvenient truck piled with baggage, and made out the sign, Byrnton.

"Oh, Burt, what were we thinking of?" she exclaimed. "This isn't the right place at all! We were to take the road up past a brick church—and there isn't any here—this is Byrnton, and we wanted Branton. What shall we do—why don't you say something?"

"Fudge!" said Burt, soberly, but in his eyes the dancing light he reserved for Anne. "I'll ask the ticket-agent."

He came out of the station, smiling. "This isn't the Branton line at all, but a short branch west of it," he informed her. "We took the wrong train, but he says lots of people make the same mistake, and they are going to change one name or the other, eventually. I am to blame, Nan, for I know this place, Byrnton; I have, or used to have, an Aunt Susan here, somewhere—shall we look her up? We have nearly three hours to kill. It will be afternoon before we can get to Branton—and Aunt Susan will give us nourishment, at least, if she's home."

"Very well," Anne assented. If Burt's business absorbed him like this, she must learn to take it philosophically.

"What a pretty place, Burt! Do see those wonderful elms!"

Byrnton proved to be an old-fashioned village, which had had the good fortune to be remodelled without being modernized. Along the main street many of the houses were square, prim little boxes, with front yards bright with sweet williams, marigolds, and candytuft; these had an iron fence around the garden, and, invariably, shutters at the front door. An occasional house stood flush with the brick or flagged sidewalk; in that case there were snowy curtains at the window, and a glimpse of hollyhocks at the back. The newer houses could be distinguished by the wide, open spaces around them; the late comers had not planned their homes to command the village street, and neighbors, as an older generation had done, but these twentieth century models did not begin until one had left the little railway station well behind.

"What a homely, homey place," said Anne, noting everything with the eye of an artist. "I don't see how you could forget it, if you have an aunt living here."

"That's the question," answered Burt. "Have I an aunt living here? She may be in California; however, in that case, the key will be under the mat."

Anne continued to look about her, with sparkling eyes. "If Aunt Milly had lived in a place like this, I'd be there yet," she told him. "The factories[268] spoiled the place for me, but they made business good for Uncle Andy and the boys, and Aunt Milly likes the bustle, she'd think this was too quiet.—Isn't it queer how people manage to get what they want—in time?"

"It is, indeed," smiled Burt. "There, Nan, that low white cottage at the very end, the last before you come to open fields. That's Aunt Susan's."

They quickened their pace; Anne was conscious of an intense wish that Aunt Susan might be home. She wanted to see the inside of the white house, bungalow, it might almost be called, if one did not associate bungalows with stucco or stained shingles. This cottage was of white wood, with the regulation green blinds. There was an outside chimney of red bricks; a pathway of red bricks in the old herringbone pattern led up to the front door, with its shining brass knocker. A row of white foxgloves stood sentinel before the front of the house, on each side the entrance, their pointed spires coming well above the window-sills; before them the dark foliage of perennial lupins, tossing up a white spray of flowers, and then it seemed as if every old-fashioned flower of white, or with a white variety, ran riot down to a border of sweet alyssum. Above all the fragrance came the unmistakable sweetness of mignonette.

"Oh, Burt!" called Anne, "I do hope she's home. What a woman she must be, I can guess some things about her, just from the outside of her house. I hope she'll show me the inside of it."

Burt shook his head. "She'd have seen us before this and been out here," he suggested. "Come 'round to the back."

The back of the premises proved no less fascinating; there was the neatest of clothes-yards, a vegetable garden, and a small garage, after which Anne regarded the silent cottage with wistful eyes.

"Those beautiful, old-fashioned flowers, no petunias but the white frilled kind,—she's an artist—and has the wash done at home," she enumerated, "and runs her automobile herself, I am sure, for she's a practical person as well; if she were just a sentimental flower-lover, she'd have had something or other climbing up the house, and it spoils the woodwork."

"It's safe to say Aunt Susan's in California," said Burt, disregarding this. "No joke, Nan, she has a married daughter who has been trying to get her out there for years, and Aunt Susan's always threatening to go. Never thought she would, but we can soon find out; I know who'll have the key."

He left Anne and walked back to the house just passed, and presently reappeared with the key. "Here you are. Aunt Susan left it with Mrs. Brown, who is to look after the place, and to use her judgment about letting people in. Aunt Susan has only been gone two days, she went hurriedly at the last, and Mrs. Brown is to close the house for her, but she hasn't got 'round to it yet. Lucky for us, there'll be everything we need for lunch; I brought eggs—see?"

Laughing like a boy. Burt unlocked the back door, and then produced four eggs, from as many pockets. He laid them carefully down upon the kitchen table.

"Now, Nan, we can use anything in the kitchen or pantry, and Mrs. Brown has a blueberry pie in the oven which she'll give us, she'll bring it over when it's done.—Want to go over the house?—Give you my word it's all right, in fact Aunt Susan told Mrs. Brown she wished she could rent it, as is, if she only knew somebody who would love it—that was her word. You can love it until the afternoon train, can't you?"

If Anne heard, she made no reply, she was exploring.

Downstairs, a wide hall occupied a central third of the house; it was well lighted by the windows each side the front door, and by double doors of glass, which opened on to the back porch. On one side the hall were kitchen and pantry, nearly equal in size, and glistening with white paint, aluminum, and blue and white porcelain. With a hasty glance[269] over these treasures, to which she was coming back, Anne stepped out into the hall again, and around to the front of the winding staircase, and entered what she knew at once for the "owner's bedroom." There were windows on two sides, as this was a front room, and each broad sill bore its own pot of ferns. The furniture here was all old-fashioned, of some dark wood that had been rubbed to a satin finish, the floor was of plain surface, with braided mats, and a blue and white counterpane provided the only bit of drapery in the room. Anne's bright head nodded with satisfaction. Here was character; to win Aunt Susan's respect would be no light task, her personal and intimate belongings showed an austere sense of values and an almost surgical cleanliness. Yet Aunt Susan could not be a martinet; her hall, furnished for other people, showed due regard for their comfort; the living room, which took the entire western side of the cottage, bore unmistakable signs of much occupancy, with wide and varied interests. A set of dark shelves, at the lower end, held china, and suggested that one might also eat at the refectory table, which was furnished as a desk and held a few books, many writing materials, and a foreign-looking lamp. There was also a piano, well littered with music, a sewing bag thrown down upon a cretonned window seat, and the generous fireplace was flanked by two huge baskets, one heaped with magazines, the other a perfectly round mound of yellow fur, which suddenly took form and life as a yellow tabby cat fastened hopeful topaz eyes upon them, blinked away a brief disappointment, and then yawned with ennui.

"His missie left him all alone," said Anne, bending to stroke the smooth head. "What's upstairs, Burt?"

"Go and look, I'll take your place with the Admiral until you come back," offered Burt, and at sound of his name the yellow cat jumped out and began rubbing against a convenient table leg. Anne found them in the same relative positions when she returned from her inspection of the upper floor.

"Your Aunt Susan must use it for sewing," she told Burt, dreamily. "With that big skylight—it could be a studio, couldn't it?"

"It is," Burt informed her. "Aunt Susan is an artist—with her needle. She gives, or gave, dressmaking lessons, in her idle moments. She gave up dressmaking, when she bought this house and settled here, but now she teaches the daughters of her old customers, they come out in automobiles every Wednesday, in winter. Saturday afternoons she has some of the young girls in the village, here,—without price—and without taste, too, some of them! And Nan, I hate to mention it, but—Aunt Susan is a pretty good cook, too!"

"Feed the brute!" quoted Nan, with a gay laugh. "Will the Admiral drink condensed milk?"

Mrs. Brown came over with her blueberry pie as Burt was summoned to luncheon. She surveyed the table, which Nan had laid in the kitchen, and then the Admiral, who was making his toilette in a thorough manner that suggested several courses, with outspoken approval.

"My, I wish Susan Winchester could pop in this minute. You found the prepared flour, and all—baked 'em on the griddle! Wa'n't that cute! I never did see an omelet like that except from Susan Winchester's own hands, and she learned from a Frenchwoman she used to sew with. Some folks can pick up every useful trick they see."

Turning to Burt, she continued:

"With all the new fangle-dangles of these days, women voting and all, you're a lucky boy to have found an old-fashioned girl!"

"I know it," said Burt, brazenly, but he did not meet Anne's astonished eyes. "My girl has learned the best of the new accomplishments, without losing what was worth keeping of the old."

Anne's judgment told her it was a good luncheon—no better than she served herself at home, though. She stared at her own slim, capable fingers. Was she domestic, after all?

"We've been looking at apartments in the city," Burt went on—"apartments in a hotel, you know.—Try the omelet, Mrs. Brown—Nan's don't fall flat as soon as other omelets do.—But we haven't found what really appeals to us."

"I should think not," declared Mrs. Brown, vigorously. "I always say a person hasn't a spark of originality that will go and live in a coop just like hundreds of others, all cut to the same pattern. Look at your Aunt Susan, now. This house belonged to old Joe Potter, he built it less'n ten years ago an Mis' Potter she had it the way she wanted it, and that was like the house she lived in when she was a girl, little, tucked-up rooms, air-tight stoves, a tidy on every chair, and she made portières out of paper beads that tickled 'em both silly—yes, and tickled everybody in the ear that went through 'em, though that wan't what I meant to say. When she died, Joe wouldn't live here, said he wouldn't be so homesick for Julia in another house, this one was full of her. So, your Aunt Susan bought it, and what did she do?

"She knocked out partitions, took down fire-boards, threw out a good parlor set and lugged in tables and chairs from all over, put big panes of glass where there was little ones—in some places, she did, and only the good angels and Susan Winchester knows why she didn't change 'em all, they're terrible mean to wash—made the front hall into a setting room and the parlor into a bedroom, got two bathrooms and no dining room—well, to make a long story short, this house is now Susan Winchester. Anybody that knows Susan would know it was her house if they see it in China.

"Did you learn to keep house with your mother?"

The transition was so abrupt that Anne started. "I—my aunt brought me up—and nine cousins," she answered. "My aunt is as unlike Burt's as you can imagine, but just as dear and good. She had a big family, and there was never time enough to have her home as she wanted it—so she thought—and I thought so, too—but yet—Aunt Milly's home was always full of happy children, and, perhaps, that's what she really wanted, more than dainty furnishings or a spotless kitchen."

"Folks, mostly, get what they want, even if they don't know it," confirmed Mrs. Brown. "Look at the Admiral, here. He don't want to come over and live with me, same as Susan meant he should. He wants to stay right in his own home, and have his meals and petting same as usual, and here you come along today and give them to him. Trouble is, folks don't always know what it is they want."

When Mrs. Brown went back to her own dinner, she left Anne with something to think about. Washing the dishes in Aunt Susan's white sink, which was fitted to that very purpose, drying them upon a rack which held every dish apart from its neighbors, and, finally, polishing the quaintly shaped pieces upon Aunt Susan's checked towel, which remained dry and spotless; opening every drawer and cupboard to see that all was left in the dainty order she had found there, Anne had a clear vision of the blue and silver furnishings at the Kensington. What had she told Burt: "It doesn't look like either of us"?—while Aunt Susan's home—

"Burt," she called, "come and answer this question. Did you come to Byrnton instead of Branton on purpose?"

"What's this?" said Burt. "Cross-examination?"

"It's an examination, surely, but I won't be cross," replied Anne, with a rare dimple. "You must answer my question truly."

"Yes, Your Honor," said Burt. "I did, Your Honor."

"Did you know your Aunt Susan wouldn't be home?"

"Our Aunt Susan," corrected Burt.—"No, Your Honor—that is, I thought—"

"You knew she was going to California?"

"Yes, Your Honor."

"This summer?"

"I didn't know exactly when—honestly, Nan, I did want you to meet her."

"Why?"'