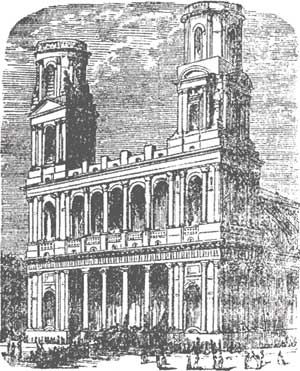

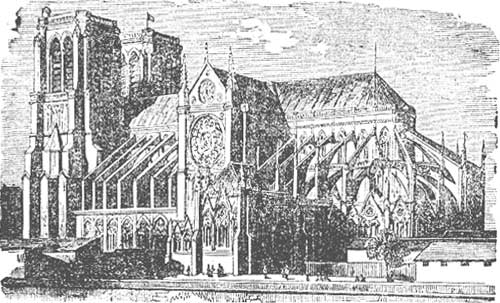

CHURCH OF ST. SULSPICE.

CHURCH OF ST. SULSPICE.

Project Gutenberg's Paris: With Pen and Pencil, by David W. Bartlett

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Paris: With Pen and Pencil

Its People and Literature, Its Life and Business

Author: David W. Bartlett

Release Date: October 25, 2005 [EBook #16943]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PARIS: WITH PEN AND PENCIL ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Sankar Viswanathan, and

Distributed Proofreaders Europe at http://dp.rastko.net

The contents of this volume are the result of two visits to Paris. The first when Louis Napoleon was president of the Republic; and the second when Napoleon III. was emperor of France. I have sketched people and places as I saw them at both periods, and the reader should bear this in mind.

I have not endeavored to make a hand-book to Paris, but have described those places and objects which came more particularly under my notice. I have also thought it best, instead of devoting my whole space to the description of places, or the manners of the people—a subject which has been pretty well exhausted by other writers—to give a few sketches of the great men of Paris and of France; and among them, a few of the representative literary men of the past. There is not a general knowledge of French literature and authors, either past or present, among the mass of readers; and Paris and France can only be truly known through French authors and literature.

My object has been to add somewhat to the general reader's knowledge of Paris and the Parisians,—of the people and the places, whose social laws are the general guide of the civilized world.

CHURCH OF ST. SULSPICE.

CHURCH OF ST. SULSPICE.

Few people now-a-days go direct to Paris from America. They land in Liverpool, get at least a birds-eye view of the country parts of England, stay in London a week or two, or longer, and then cross the channel for Paris.

The traveler who intends to wander over the continent, here takes his initiatory lesson in the system of passports. I first called upon the American minister, and my passport—made out in Washington—was visé for Paris. My next step was to hunt up the French consul, and pay him a dollar for affixing his signature to the precious document. At the first sea-port this passport was taken from me, and a provisional one put into my keeping. At Paris the original one was returned! And this is a history of my passport between London and Paris, a distance traversed in a few hours. If such are the practices between two of the greatest and most civilized towns on the face of the earth, how unendurable must they be on the more despotic continent?

The summer was in its first month, and Paris was in its glory, and it was at such a time that I visited it. We took a steamer at the London bridge wharf for Boulogne. [Pg 14]The day promised well to be a boisterous one, but I had a very faint idea of the gale blowing in the channel. If I could have known, I should have waited, or gone by the express route, via Dover, the sea transit of which occupies only two hours. The fare by steamer from London to Boulogne was three dollars. The accommodations were meager, but the boat itself was a strong, lusty little fellow, and well fitted for the life it leads. I can easily dispense with the luxurious appointments which characterize the American steamboats, if safety is assured to me in severe weather.

The voyage down the Thames, was in many respects very delightful. Greenwich, Woolwich, Margate, and Ramsgate lie pleasantly upon this route. But the wind blew so fiercely in our teeth that we experienced little pleasure in looking at them. When we reached the channel we found it white with foam, and soon our little boat was tossed upon the waves like a gull. In my experience crossing the Atlantic, I had seen nothing so disagreeable as this. The motion was so quick and so continual, the boat so small, that I very soon found myself growing sick. The rain was disagreeable, and the sea was constantly breaking over the bulwarks. I could not stay below—the atmosphere was too stifling and hot. So I bribed a sailor to wrap about me his oil-cloth garments, and lay down near the engines with my face upturned to the black sky, and the sea-spray washing me from time to time. Such sea-sickness I never endured, though before I had sailed thousands of miles at sea, and have done the same since. From sundown till two o'clock the next morning I lay on the deck of the sloppy little boat, and when at last the Boulogne lights were to be seen, I was as heartily glad as ever in my life.

Thoroughly worn out, as soon as I landed upon the quay I handed my keys to a commissaire, gave up my passport, and sought a bed, and was soon in my dreams tossing again upon the channel-waves. I was waked by the commissaire, who entered my room with the keys. He had passed my baggage, got a provisional passport for me, and now very politely advised me to get up and take the first train to Paris, for I had told him I wished to be in Paris as soon as possible. Giving him a good fee for his trouble, and hastily quitting the apartment and paying for it, I was very soon in the railway station. My trunks were weighed, and I bought baggage tickets to Paris—price one sou. The first class fare was twenty-seven francs, or about five dollars, the distance one hundred and seventy miles. This was cheaper than first class railway traveling in England, though somewhat dearer than American railway prices.

The first class cars were the finest I have seen in any country—very far superior to American cars, and in many respects superior to the English. They were fitted up for four persons in each compartment, and a door opened into each from the side. The seat and back were beautifully cushioned, and the arms were stuffed in like manner, so that at night the weary traveler could sleep in them with great comfort.

The price of a third class ticket from Boulogne to Paris was only three dollars, and the cars were much better than the second class in America, and I noticed that many very respectably dressed ladies and gentlemen were in them—probably for short distances. It is quite common, both in England and France, in the summer, for people of wealth to travel by rail for a short distance by the cheapest class of cars.

I entered the car an utter stranger—no one knew me, and I knew no one. The language was unintelligible, for I found that to read French in America, is not to talk French in France. I could understand no one, or at least but a word here and there.

But the journey was a very delightful one. The country we passed through was beautiful, and the little farms were in an excellent state of cultivation. Flowers bloomed everywhere. There was not quite that degree of cultivation which the traveler observes in the best parts of England, but the scenery was none the less beautiful for that. Then, too, I saw everything with a romantic enthusiasm. It was the France I had read of, dreamed of, since I was a school-boy.

A gentleman was in the apartment who could talk English, having resided long in Boulogne, which the English frequent as a watering place, and he pointed out the interesting places on our journey. At Amiens we changed cars and stopped five minutes for refreshments. I was hungry enough to draw double rations, but I felt a little fear that I should get cheated, or could not make myself understood; but as the old saw has it, "Necessity is the mother of invention," and I satisfied my hunger with a moderate outlay of money. A few miles before we reached Paris, we stopped at the little village of Enghein, and it seemed to me that I never in my life had dreamed of so fairy-like a place. Beautiful lakes, rivers, fountains, flowers, and trees were scattered over the village with exquisite taste. To this place, on Sundays and holidays, the people of Paris repair, and dance in its cheap gardens and drink cheap wines.

When we reached Paris my trunks were again searched and underwent a short examination, to see that no wines [Pg 17]or provisions were concealed in them. A tax is laid upon all such articles when they enter the city, and this is the reason why on Sunday the people flock out of town to enjoy their fêtes. In the country there are no taxes on wine and edibles, and as a matter of economy they go outside of the walls for their pleasure.

When my baggage was examined, I took an omnibus to the hotel Bedford, Rue de l'Arcade, where I proposed to stay but a few days, until I could hunt up permanent apartments. My room was a delightful one and fitted up in elegant style. I was in the best part of Paris. Two minutes walk away were the Champs Elysees—the Madeleine church, the Tuileries, etc., etc. But I was too tired to go out, and after a French dinner and a lounge in the reading-room, I went to sleep, and the next morning's sun found me at last entirely recovered from my wretched passage across the channel.

My second trip to Paris was in many respects different from the first—which I have just described. The route was a new one, and pleasanter than that via Boulogne. Our party took an express train from the London bridge terminus for Newhaven, a small sea-port. The cars were fitted up with every comfort, and we made the passage in quick time. At three P.M. we went on board a little steamer for Dieppe, where we arrived at nine o'clock. After a delay of an hour we entered a railway carriage fitted up in a very beautiful and luxurious style. At Dieppe we had no trouble with our passports, keeping the originals, and simply showing them to the custom-house officials. Our ride to Paris was in the night, yet was very comfortable.

In coming back to London, we made the trip to Dieppe in the daytime, and found it to be very beautiful. From Paris to Rouen the railway runs a great share of the way in sight of the river Seine, and often upon its banks. Many of the views from the train were romantic, and some of them wildly grand. Upon the whole, this route is the pleasantest between Paris and London, as it is one of the cheapest. There is one objection, however, and that is the length of the sea voyage—six hours. Those who dislike the water will prefer the Dover route.

The origin of Paris is not known. According to certain writers, a wandering tribe built their huts upon the island now called la Cité. This was their home, and being surrounded by water, it was easily defended against the approach of hostile tribes. The name of the place was Lutetia, and to themselves they gave the name of Parisii, from the Celtic word par, a frontier or extremity.

This tribe was one of sixty-four which were confederated, and when the conquest of Gaul took place under Julius Caesar, the Parisii occupied the island. The ground now covered by Paris was either a marsh or forest, and two bridges communicated from the island to it. The islanders were slow to give up their Druidical sacrifices, and it is doubtful whether the Roman gods ever were worshiped by them, though fragments of an altar of Jupiter have been found under the choir of the cathedral of Notre Dame. Nearly four hundred years after Christ, the Emperor Julian remodeled the government and laws of Gaul and Lutetia, and changed its name to Parisii. It then, too, became a city, and had considerable [Pg 19]trade. For five hundred years Paris was under Roman domination. A palace was erected for municipal purposes in the city, and another on the south bank of the Seine, the remains of which can still be seen. The Roman emperors frequently resided in this palace while waging war with the northern barbarians. Constantine and Constantius visited it; Julian spent three winters in it; Valentian and Gratian also made it a temporary residence.

The monks have a tradition that the gospel was first preached in Paris about the year 250, by St. Denis, and that he suffered martyrdom at Montmartre. A chapel was early erected on the spot now occupied by Notre Dame. In 406 the northern barbarians made a descent upon the Roman provinces, and in 445 Paris was stormed by them. Before the year 500 Paris was independent of the Roman domination. Clovis was its master, and marrying Clotilde, he embraced Christianity and erected a church. The island was now surrounded by walls and had gates. The famous church of St. German L'Auxerrois was built at this time. For two hundred and fifty years, Paris retrograded rather than advanced in civilization, and the refinements introduced by the Romans were nearly forgotten. In 845 the Normans sacked and burnt Paris. Still again it was besieged, but such was the valor of its inhabitants that the enemy were glad to raise the siege. Hugues Capet was elected king in 987, and the crown became hereditary. In his reign the Palace of Justice was commenced. Buildings were erected on all sides, and new streets were opened. Under Louis le Gros the Louvre was rebuilt, it having existed since the time of Dagobert. Bishop Sully began the foundations of Notre Dame in 1163, and about that time the Knights Templars erected a palace.

Under the reign of Philip Augustus many of the public edifices were embellished and new churches and towers were built. In 1250 Robert Serbon founded schools—a hospital and school of surgery were also about this time commenced.

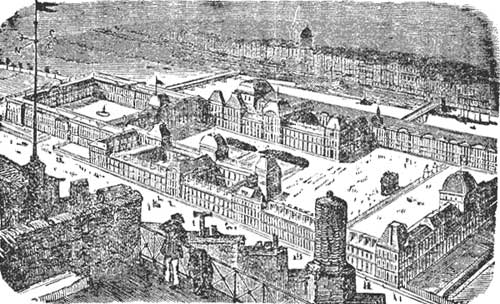

Under Charles V. the city flourished finely, and the Bastille and the Palace de Tourvelles were erected. The Louvre also was repaired. Next came the unhappy reign of Charles VI., who was struck with insanity. In 1421 the English occupied Paris, but under Charles VII. they were driven from it and the Greek language was taught for the first time in the University of Paris. It had then twenty-five thousand students. Under the reign of successive monarchs Paris was, from famine and plague, so depopulated that its gates were thrown open to the malefactors of all countries. In 1470 the art of printing was introduced into the city and a post-office was established. In the reign of Francis I. the arts and literature sprang into a new life. The heavy buildings called the Louvre were demolished, and a new palace commenced upon the old site. In 1533 the Hotel de Ville was begun, and many fine buildings were erected. The wars of the sects, or rather religions, followed, and among them occurred the terrible St. Bartholomew massacre. Henry IV. brought peace to the kingdom and added greatly to the beauty and attractiveness of Paris.

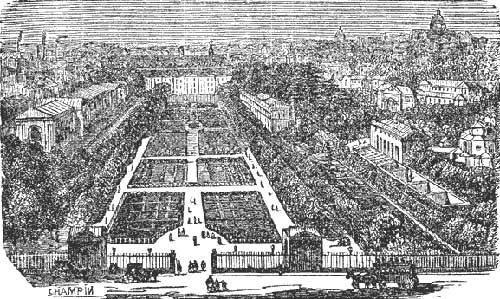

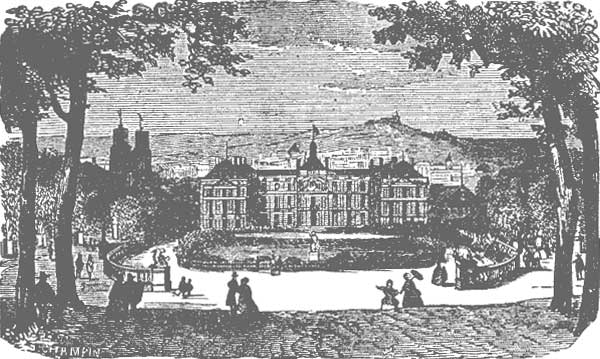

Under Louis XIII. several new streets were opened, and the Palais Royal and the palace of the Luxembourg begun. Under the succeeding king the wars of the Fronde occurred, but the projects of the preceding king were carried out, and more than eighty new streets were opened. The planting of trees in the Champs Elysees, also took place under the reign of Louis XIV. The pal[Pg 21]ace of the Tuileries was enlarged, the Hotel des Invalides, a foundling hospital, and several bridges were built.

Louis XV. established the manufactory of porcelain at Sevres, and also added much to the beauty of Paris. He commenced the erection of the Madeleine. Theaters and comic opera-houses were speedily built, and water was distributed over the city by the use of steam-engines.

Then broke out the revolution, and many fine monuments were destroyed. But it was under the Directory that the Museum of the Louvre was opened, and under Napoleon the capital assumed a splendor it had never known before. Under the succeeding kings it continued to increase in wealth and magnificence, until it is unquestionably the finest city in the world.

I have now in a short space given the reader a preliminary sketch of Paris, and will proceed at once to describe what I saw in it, and the impressions I received, while a resident in that city.

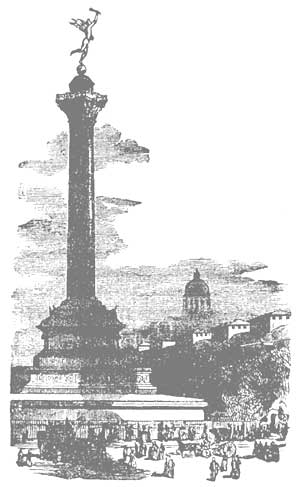

BOULEVARD DU TEMPLE.

BOULEVARD DU TEMPLE.

The first thing the stranger does in Paris, is of course to find temporary lodging, and the next is to select a good restaurant. Paris without its restaurants, cafés, estaminets, and cercles, would be shorn of half its glory. They are one of its most distinguished and peculiar features. Between the hours of five and eight, in the evening of course, all Paris is in those restaurants. The scene at such times is enlivening in the highest degree. The Boulevards contain the finest in the city, for there nearly all the first-class saloons are kept. There are retired streets in which are kept houses on the same plan, but [Pg 25]with prices moderate in the extreme. You can go on the Boulevards and pay for a breakfast, if you choose, fifty or even sixty francs, or you can retire to some quiet spot and pay one franc for your frugal meal. It is of course not common for any one to pay the largest sum named, but there are persons in Paris who do it, young men who with us are vulgarly denominated "swells," and who like to astonish their friends by their extravagance.

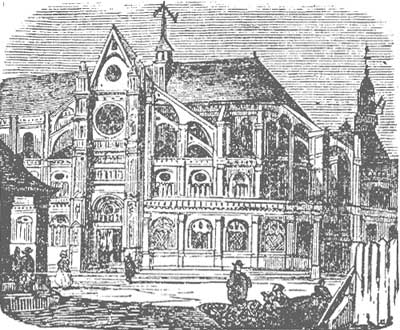

PARIS & ARCH OF TRIUMPH.

PARIS & ARCH OF TRIUMPH.

Out of curiosity I went one day with a friend to one of the most gorgeous of the restaurants on the Boulevards. Notwithstanding the descriptions I had read and listened to from the lips of friends, I was surprised at the splendor and style of the place. We sat down before a fine window which was raised, looking into the street. Indeed, so close sat we to it that the fashionable promenaders could each, if he liked, have peeped into our dishes. But Parisians never trouble strangers with their inquisitiveness. We sat down before a table of exquisite marble, and a waiter dressed as neatly, and indeed gracefully, as a gentleman, handed us a bill of fare. It was long enough in itself to make a man a dinner, if the material were only palatable. Including dessert and wines, there were one hundred specifications! There were ten kinds of meat, and fourteen varieties of poultry. Of course there were many varieties of game, and there were eight kinds of pastry. Of fish there were fourteen kinds, there were ten side dishes, a dozen sweet dishes, and a dozen kinds of wine.

The elegance of the apartment can scarcely be imagined, and the savory smell which arose from neighboring tables occupied by fashionable men and women, invited us to a repast. We called, however, but for a dish or two, and after we had eaten them, we had coffee, and over our [Pg 26]cups gazed out upon the gay scene before us. It was novel, indeed, to the American eye, and we sat long and discussed it. In this restaurant there were private rooms, called Cabinets de Societe, and into them go men and women at all hours, by day and night. It is also a common sight to see the public apartments of the restaurants filled with people of both sexes. Ladies sit down even in the street with gentlemen, to sup chocolate or lemonade. There is not much eaves-dropping in Paris, and you can do as you please, nor fear curious eyes nor scandal-loving tongues. This is very different from London. There, if you do any thing out of the common way, you will be stared at and talked about. There, if you take a lady into a public eating-house, her position, at least, will not be a very pleasant one.

There are many places in the Palais Royal, the basement floor of which, fronting upon the court of the palace, is given up to shops, where for two or three francs a dinner can be purchased which will consist of soup, two dishes from a large list at choice, a dessert, and bread and wine. There are places, indeed, where for twenty-five sous a dinner sufficient to satisfy one's hunger can be purchased, but I must confess that while in Paris I could never yet make up my mind to patronize a cheap restaurant. I knew too well, by the tales of more experienced Parisians, the shifts to which the cook of one of these cheap establishments is sometimes reduced to produce an attractive dish. The material sometimes would not bear a close examination—much less the cuisine.

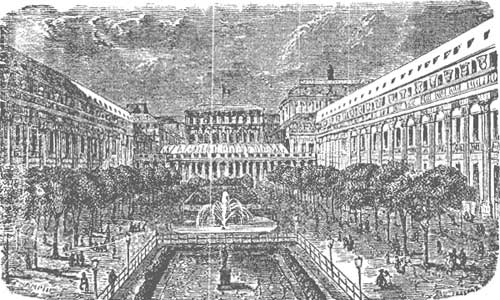

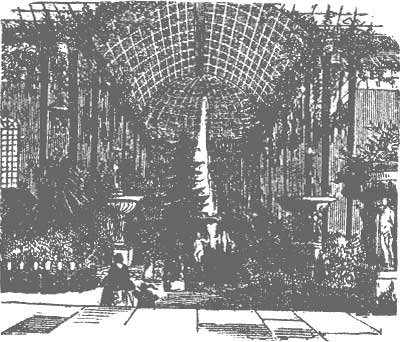

JARDIN DU PALAIS ROYAL.

JARDIN DU PALAIS ROYAL.

I was astonished to see the quantities of bread devoured by the frequenters of the eating-houses, but I soon equaled my neighbors. Paris bread is the best in the world, or at least, it is the most palatable I ever tasted. [Pg 29]It is made in rolls six feet long, and sometimes I have seen it eight feet long. Before now, I have seen a couple dining near the corner of a room, with their roll of bread thrown like a cane against the wall, and as often as they wanted a fresh slice, the roll was very coolly brought over and decapitated. The Frenchman eats little meat, but enormously of the staff of life. The chocolate and coffee which are to be had in the French cafés, are very delicious, and though after a fair and long trial I never could like French cookery as well as the English, yet I would not for a moment pretend that any cooks in the world equal those of Paris in the art of imparting exquisite flavor to a dish. It is quite common for the French to use brandy in their coffee.

People who take apartments in Paris often prefer to have their meals sent to their private rooms, and by a special bargain this is done by any of the restaurants, but more especially by a class of houses called traiteurs, whose chief business is to furnish cooked dishes to families in their own homes. In going to a hotel in Paris, the stranger never feels in the slightest degree bound to get his meals there. He hires his room and that is all, and goes where he pleases. The cafés are in the best portions of the town, magnificent places, often exceeding in splendor the restaurants. They furnish coffee, chocolate, all manner of ices and fruits, and cigars. At these places one meets well-dressed ladies, and more than once in them I have seen well-dressed women smoking cigarettes. Love intrigues are carried on at these places, for a Paris lady can easily steal from her home to such a place under cover of the night. A majority, however, of the women to be seen at such places, are those who have no position in society, the wandering nymphs of the night, or the poor [Pg 30]grisettes. It is not strange that the poor shop-girl is easily attracted to such gorgeous places by men far above her in station.

Outside of all the cafés little tables are placed on the pavement, with chairs around them. These places are delightful in the summer evenings, and are always crowded. A promenade through some of the best streets of a summer night is a brilliant spectacle, and more like a promenade through a drawing-room than through an American street. The proprietors of those places do not intend to keep restaurants, but quite a variety of food, hot or cold, is always on hand, and wines of all kinds are sold.

I well remember my first visit to a French café. It was when Louis Napoleon was president, not emperor of France, and when there was more liberty in Paris than there is now. I dropped into one near the Boulevards, which, while it contained everything which could add to one's comfort, still was not one of the first class. Several officers were dining in it, and in some way I came in contact with one of them in such a manner that he discovered I was an American. At once his conduct toward me was of the most cordial kind, and his fellows rose and bade me welcome to France. The simple fact that I was a republican from America aroused the enthusiasm of all. I found, afterward, that the regiment to which these officers belonged was suspected by the president of being democratic in its sympathies.

The reading-rooms of Paris are one of its best institutions. They are scattered all over the city, but the best is Galignani's, which contains over twenty thousand volumes in all languages. The subscription price for a month is eight francs, for a fortnight five francs, and for a day ten sous.

There are reading-rooms furnished only with newspapers, where for a small sum of money one can read the papers. These places are few in comparison with their numbers in the days of the republic, however. Under the despotic rule of Louis Napoleon, the newspaper business has drooped.

An anonymous writer in one of Chambers' publications, tells a good story, and it is a true one, of Père Fabrice, who amassed a fortune in Paris. The story is told as follows:

"He had always a turn for speculation, and being a private soldier he made money by selling small articles to his fellow soldiers. When his term of service had expired, he entered the employ of a rag-merchant, and in a little while proposed a partnership with his master, who laughed at his impudence. He then set up an opposition shop, and lost all he had saved in a month. He then became a porter at the halles where turkeys were sold. He noticed that those which remained unsold, in a day or two lost half their value. He asked the old women how the customers knew the turkeys were not fresh. They replied that the legs changed from a bright black to a dingy brown. Fabrice went home, was absent the next day from the halles, and on the third day returned with a bottle of liquid. Seizing hold of the first brown-legged turkey he met with, he forthwith painted its legs out of the contents of his bottle, and placing the thus decorated bird by the side of one just killed, he asked who now was able to see the difference between the fresh bird and the stale one? The old women were seized with admiration. They are a curious set of beings, those dames de la halle; their admiration is unbounded for successful adventurers—witness their enthusiasm for Louis Napoleon. They [Pg 32]adopted our friend's idea without hesitation, made an agreement with him on the principle of the division of profits; and it immediately became a statistical puzzle with the curious inquirers on these subjects, how it came to pass that stale turkeys should have all at once disappeared from the Paris market? It was set down to the increase of prosperity consequent on the constitutional régime and the wisdom of the citizen-king. The old women profited largely; but unfortunately, like the rest of the world, they in time forgot both their enthusiasm and their benefactor, and Père Fabrice found himself involved in a daily succession of squabbles about his half-profits. Tired out at last, he made an arrangement with the old dames, and, in military phrase, sold out. Possessed now of about double the capital with which he entered, he recollected his old friend, the rag-merchant, and went a second time to propose a partnership. 'I am a man of capital now,' he said; 'you need not laugh so loud this time.' The rag-merchant asked the amount of his capital; and when he heard it, whistled Ninon dormait, and turned upon his heel. 'No wonder,' said Fabrice afterward; 'I little knew then what a rag-merchant was worth. That man could have bought up two of Louis Philippe's ministers of finance.' At the time, however, he did not take the matter so philosophically, and resolved, after the fashion of his class, not to drown himself, but to make a night of it. He found a friend, and went with him to dine at a small eating-house. While there, they noticed the quantity of broken bread thrown under the tables by the reckless and quarrelsome set that frequented the place; and his friend remarked, that if all the bread so thrown about were collected, it would feed half the quartier. Fabrice said nothing; but he was in search of an idea, and he [Pg 33]took up his friend's. The next day, he called on the restaurateur, and asked him for what he would sell the broken bread he was accustomed to sweep in the dustpan. The bread he wanted, it should be observed, was a very different thing from the fragments left upon the table; these had been consecrated to the marrow's soup from time immemorial. He wanted the dirty bread actually thrown under the table, which even a Parisian restaurateur of the Quartier Latin, whose business it was to collect dirt and crumbs, had hitherto thrown away. Our restaurateur caught eagerly at the offer, made a bargain for a small sum; and Master Fabrice forthwith proceeded to about a hundred eating-houses of the same kind, with all of whom he made similar bargains. Upon this he established a bakery, extending his operations till there was scarcely a restaurant in Paris of which the sweepings did not find their way to the oven of Père Fabrice. Hence it is that the fourpenny restaurants are supplied; hence it is that the itinerant venders of gingerbread find their first material. Let any man who eats bread at any very cheap place in the capital take warning, if his stomach goes against the idea of a réchauffé of bread from the dust-hole. Fabrice, notwithstanding some extravagances with the fair sex, became a millionaire; and the greatest glory of his life was—that he lived to eclipse his old master, the rag-merchant."

The same writer also gives a graphic description of one class of restaurants in Paris—the pot-luck shops:

"Pot-luck, or the fortune de pot, is on the whole the most curious feeding spectacle in Europe. There are more than a dozen shops in Paris where this mode of procuring a dinner is practiced, chiefly in the back streets abutting on the Pantheon. About two o'clock, a parcel [Pg 34]of men in dirty blouses, with sallow faces, and an indescribable mixture of recklessness, jollity, and misery—strange as the juxtaposition of terms may seem—lurking about their eyes and the corners of their mouths, take their seats in a room where there is not the slightest appearance of any preparation for food, nothing but half-a-dozen old deal-tables, with forms beside them, on the side of the room, and one large table in the middle. They pass away the time in vehement gesticulation, and talking in a loud tone; so much of what they say is in argot, that the stranger will not find it easy to comprehend them. He would think they were talking crime or politics—not a bit of it; their talk is altogether about their mistresses. Love and feeding make up the existence of these beings; and we may judge of the quality of the former by what we are about to see of the latter. A huge bowl is at last introduced, and placed on the table in the middle of the room. At the same time a set of basins, corresponding to the number of the guests, are placed on the side-tables. A woman, with her nose on one side, good eyes, and the thinnest of all possible lips, opening every now and then to disclose the white teeth which garnish an enormous mouth, takes her place before it. She is the presiding deity of the temple; and there is not a man present to whom it would not be the crowning felicity of the moment to obtain a smile from features so little used to the business of smiling, that one wonders how they would set about it if the necessity should ever arise. Every cap is doffed with a grim politeness peculiar to that class of humanity, and a series of compliments fly into the face of Madame Michel, part leveled at her eyes, and part at the laced cap, in perfect taste, by which those eyes are shrouded. Mère Michel, however, says nothing in return, [Pg 35]but proceeds to stir with a thick ladle, looking much larger than it really is, the contents of the bowl before her. These contents are an enormous quantity of thick brown liquid, in the midst of which swim numerous islands of vegetable matter and a few pieces of meat. Meanwhile, a damsel, hideously ugly—but whose ugliness is in part concealed by a neat, trim cap—makes the tour of the room with a box of tickets, grown black by use, and numbered from one to whatever number may be that of the company. Each of them gives four sous to this Hebe of the place, accompanying the action with an amorous look, which is both the habit and the duty of every Frenchman when he has anything to do with the opposite sex, and which is not always a matter of course, for Marie has her admirers, and has been the cause of more than one rixe in the Rue des Anglais. The tickets distributed, up rises number one—with a joke got ready for the occasion, and a look of earnest anxiety, as if he were going to throw for a kingdom—takes the ladle, plunges it into the bowl, and transfers whatever it brings up to his basin. It is contrary to the rules for any man to hesitate when he has once made his plunge, though he has a perfect right to take his time in a previous survey of the ocean—a privilege of which he always avails himself. If he brings up one of the pieces of meat, the glisten of his eye and the applauding murmur which goes round the assembly give him a momentary exultation, which it is difficult to conceive by those who have not witnessed it. In this the spirit of successful gambling is, beyond all doubt, the uppermost feeling; it mixes itself up with everything done by that class of society, and is the main reason of the popularity of these places with their habitués; for when the customers have once acquired the habit, they rarely go anywhere else."

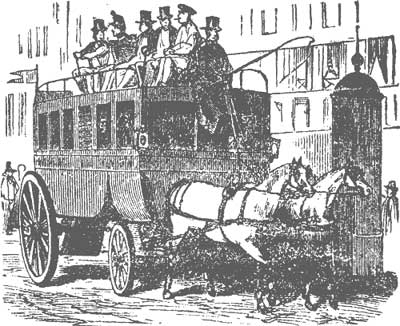

OMNIBUS.

OMNIBUS.

One of my first days in Paris I sauntered out to find some American newspapers, that I might know something of what had transpired in America for weeks previous. I directed my steps to the office of Messrs. Livingston, Wells & Co., where I had been informed a reading-room was always kept open for the use of American strangers in Paris. The morning was a delightful one, and I could but contrast it with the usual weather of London. During months of residence in the English metropolis I had seen no atmosphere like this, and my spirits, like the sky, were clear and bright.

On my way I saw a novel sight, and to me the first intimation that the people of Paris, so widely famed for their politeness, refinement, and civilization, are yet addicted to certain practices for which the wildest barbarian in the far west would blush. I saw men in open day, in the open walk, which was crowded with women as well as [Pg 37]men, commit nuisances of a kind I need not particularize but which seemed to excite neither wonder nor disgust in the by-passers. Indeed I saw they were quite accustomed to such sights, and their nonchalance was only equaled by that of the well-dressed gentlemen who were the guilty parties. I very soon learned more of Paris, and found that not in this matter alone were its citizens deficient in refinement, but in still weightier matters.

I soon reached the American reading-room, and walked in. My first act was to look at the register where all persons who call inscribe their names, and I was surprised to notice the number of Americans present in Paris. It only proved what I long had heard, that Americans take more naturally to the French than to the sturdy, self-sufficient Englishman. As it is in the matter of fashions, so it is regarding almost everything else, save morals, and I doubt if the tone of fashionable society in New York is any better than in Paris.

I was heartily rejoiced to take an American newspaper in my hand again. There were the clear open face of the plain-spoken Tribune, the sprightly columns of the Times, and the more dignified columns of the Washington journals. There were also many other familiar papers on the table, and they were all touched before I left. It was like a cool spring in the wide desert. For I confess that I love the newspaper, if it only be of the right sort. From early habit, I cannot live without it. Let any man pursue the vocation of an editor for a few years, and he will find it difficult, after, to live without a good supply of newspapers, and they must be of the old-fashioned home kind.

I did not easily accustom myself to the Paris journals. Cheap enough some of them were, but still the strange language was an obstacle. They are worse printed than [Pg 38]ours, and are by no means equal to such journals as the Times and Tribune. They publish continued stories, or novels, and racy criticisms of music, art, and literature. The political department of the French newspaper at the present day is the weakest part of the sheet. It is lifeless. A few meager facts are recorded, and there is a little tame comment, and that is all. There was a time when the political department of a French newspaper was its most brilliant feature. During the exciting times which presaged the downfall of Louis Philippe, and also during the early days of the republic, the Paris press was in the full tide of success, and was exceedingly brilliant. The daily journals abounded, and their subscription lists were enormous. Where there is freedom, men and women will read—and where there is unmitigated despotism, the people care little to read the sickly journals which are permitted to drag out an existence.

There is one journal published in Paris in the English language, "Galignani's Messenger." It is old, and in its way is very useful, but it is principally made up of extracts from the English journals. It has no editorial ability or originality, and of course never advances any opinion upon a political question.

On my return home I passed through a street often mentioned by Eugene Sue in his Mysteries of Paris—a street formerly noted for the vile character of its inhabitants. It was formerly filled with robbers and cut-throats, and even now I should not care to risk my life in this street after midnight, with no policemen near. It is exceedingly narrow, for I stood in the center and touched with the tips of my fingers the walls of both sides of the street. It is very dark and gloomy, and queer-looking passages run up on either side from the street. Some of [Pg 39]them were frightful enough in their appearance. To be lost in such a place in the dead of night, even now, would be no pleasant fate, for desperate characters still haunt the spot. Possibly the next morning, or a few mornings after, the stranger's body might be seen at La Morgue. That is the place where all dead bodies found in the river or streets are exhibited—suicides and murdered men and women.

Talking of this street and its reputation in Eugene Sue's novels, reminds me of the man. When I first saw it he had just been elected to the Chamber of Deputies by an overwhelming majority. It was not because Sue was the favorite candidate of the republicans, but he stood in such a position that his defeat would have been considered a government victory, and consequently he was elected. I was glad to find the man unpopular among democrats of Paris, for his life, like his books, has many pages in it that were better not read. At that time he was living very quietly in a village just out of Paris, and though surrounded with voluptuous luxuries, he was in his life strictly virtuous. He was the same afterward, and being very wealthy, gave a great deal to the poor. His novels are everywhere read in France.

I was not a little surprised during my first days in Paris to see the popularity of Cooper as a novelist. His stories are for sale at every book-stall, and are in all the libraries. They are sold with illustrations at a cheap rate, and I think I may say with safety that he is as widely read in France as any foreign novelist. This is a little singular when it is remembered how difficult it is to convey the broken Indian language to a French reader. This is one of the best features of Cooper's novels—the striking manner in which he portrays the language of the North [Pg 40]American Indian and his idiomatic expressions. Yet such is the charm of his stories that they have found their way over Europe. The translations into the French language must be good.

Another author read widely in Paris, as she is all over Europe, is Mrs. Stowe. Uncle Tom is a familiar name in the brilliant capital of France, and even yet his ideal portraits hang in many shop windows, and the face of Mrs. Stowe peeps forth beside it. Uncle Tom's Cabin was wonderfully popular among all classes, and to very many—what a fact!—it brought their first idea of Jesus Christ as he is delineated in the New Testament. But Mrs. Stowe's Sunny Memories was very severely criticised and generally laughed at—especially her criticisms upon art.

Walking one evening in the Champs Elysees, I found a little family of singers from the Alps, underneath one of the large trees. You should have heard them sing their native songs, so plaintive and yet so mild. Father and mother, two little sisters and a brother, were begging their bread in that way. They were dressed very neatly, although evidently extremely poor. The father had a violin which he played very sweetly, the mother sang, the two little girls danced, and the boy put in a soft and melancholy tenor. I hardly ever listened to sadder music. It seemed as if their hearts were in it, saddened at the thought of exile from their native mountains. After singing for a long time, they stopped and looked up appealingly to the crowd—but not a sou fell to the ground. Once more they essayed to sing, with a heavier sorrow upon their faces, for they were hungry and had no bread. They stopped again—not a solitary sou was given to them. A large tear rolled down the cheek of the father—you should have seen the answering impulse of the crowd—how the [Pg 41]sous rattled upon the ground. They saw instantly that it was no common beggar before them, but one who deserved their alms. At once, as if a heaven full of clouds had divided and the sunshine flashed full upon their faces, the band of singers grew radiant and happy. Such is life—a compound of sorrow and gayety.

The Parisian omnibus system is the best in the world, and I found it very useful and agreeable always while wandering over the city. The vehicles are large and clean, and each passenger has a chair fastened firmly to the sides of the carriage. Six sous will carry a person anywhere in Paris, and if two lines are necessary to reach the desired place, a ticket is given by the conductor of the first omnibus, which entitles the holder to another ride in the new line. The omnibus system is worked to perfection only in Paris, and is there a great blessing to people who cannot afford to drive their own carriages.

The Paris Exchange is on the Rue Vivienne, and is approached from the Tuileries from that street or via the Palais National, and a succession of the most beautiful arcade-shops in Paris or the world. If the day be rainy, the stranger can thread his way to it under the long arcades as dry as if in his own room at the hotel. I confess to a fondness for wandering though such places as these arcades, where the riches of the shops are displayed in their large windows. In America it is not usual to fill the windows of stores full of articles with the price of each attached, but it is always so in London and Paris. A [Pg 42]jewelry store will exhibit a hundred kinds of watches with their different prices attached, and the different shops will display what they contain in like manner. There are, too, in Paris and London places called "Curiosity shop". The first time I ever saw one of these shops with its green windows and name over the door, memory instantly recalled a man never to be forgotten. Will any one who has read Charles Dickens ever forget his "Curiosity Shop," the old grandfather and little Nell? When I entered the shop—the windows filled with old swords, pistols, and stilettos—it seemed to me that I must meet the old gray-haired man, or gentle Nell, or the ugly Quilp and Dick Swiveller. But they were not there.

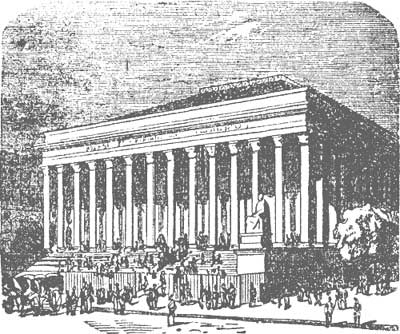

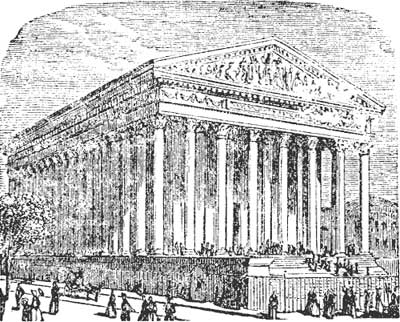

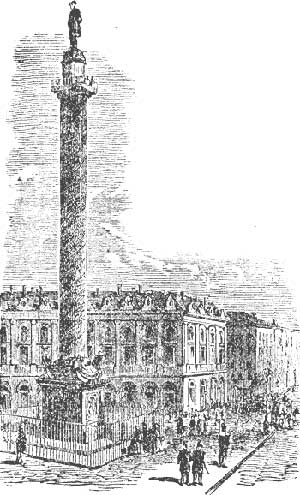

PALAIS DE LA BOURSE

PALAIS DE LA BOURSE

But I have been stopping in a curiosity shop when I should be on my way to the Bourse. The Paris Bourse, or Exchange, is perhaps the finest building of its kind on the continent. Its magnificence is very properly of the [Pg 43]most solid and substantial kind. For should not the exchange for the greatest merchants of Paris be built in a stable rather than in a slight and beautiful manner? The form of the structure is that of a parallelogram, and it is two hundred and twelve by one hundred and twenty-six feet. It is surrounded by sixty-six Corinthian columns, which support an entablature and a worked attic. It is approached by a flight of steps which extend across the whole western front. Over the western entrance is the following inscription—BOURSE ET TRIBUNAL DE COMMERCE. The roof is made of copper and iron. The hall in the center of the building where the merchants meet is very large—one hundred and sixteen feet long and seventy-six feet broad. Just below the cornice are inscribed the names of the principal cities in the world, and over the middle arch there is a clock, which on an opposite dial-plate marks the direction of the wind out of doors.

The hall is lighted from the roof—the ceiling is covered with fine paintings, or as they are styled "monochrane drawings." Europe, Asia, Africa, and America are represented in groups. In one, the city of Paris is represented as delivering her keys to the God of Commerce, and inviting Commercial Justice to enter the walls prepared for her.

The hall is paved with a fine marble, and two thousand persons can be accommodated upon the central floor. There is a smaller inclosure at the east end, where the merchants and stockholders transact their daily business. The hours are from one o'clock to three for the public stocks, and till half past five for all others. The public is allowed to visit the Bourse from nine in the morning till five at night. A very singular regulation exists in reference to the ladies. No woman is admitted into the Bourse [Pg 44]without a special order from the proper authorities. The cause for this is the fact that years ago, when ladies were admitted to the Bourse, they became very much addicted to gambling there, and also enticed the gentlemen into similar practices. It is not likely that the old stockholders were tempted into any vicious practices, but the presence of women was enough to attract another class of men—idlers and fashionable gamblers—until the exchange was turned into a gambling-saloon. The matter was soon set to rights when women were shut out.

Paris was formerly without an Exchange, and the merchants held their meetings in an old building which John Law, the celebrated financier, once occupied. They afterward met in the Palais Royal, and still later, in a comparatively obscure street. The first stone of the Bourse was laid on the 28th of March, 1808, and the works proceeded with dispatch till 1814, when they were suspended. It was completed in 1826. The architect who designed it died when it was half completed, but the plan was carried out, though by a new architect. It is now a model building of its kind, and cost nearly nine millions of francs. In comprehensive magnificence it has no rival in Paris—perhaps not in the world. The Royal Exchange of London, though a fine building, is a pigmy beside this massive and colossal structure. The best view can be obtained from the Rue Vivienne. From this street one has a fine view of the fine marble steps ascending to it, and which stretch completely across the western part.

The history of all the great panics which have been experienced on the Paris Exchange would be an excellent history of the fortunes of France. The slightest premonition of change is felt at once at the Bourse, and as each successive revolution has swept over the country, it has [Pg 45]written its history in ineffaceable characters on Change. Panic has followed panic, and the stocks fly up or down according to the views outside. The breath of war sets all its interests into a trembling condition, and an election, before now, has sent the thrill to the very center of that grand old money-palace.

On my way home from the Bourse, I stopped to go over Galignani's Reading Room. It is a capital collection of the best books of all countries, some of them in French, some in English, and others in German. I found on the shelves many American republications, but Cooper was always first among these. For a small sum the stranger can subscribe to this library, either for a month or a year, and supply himself with reading and the newspapers of the world.

The Messrs. Galignani publish an English journal in Paris. It is a daily, and has no opinions of its own. Of course, an original and independent journal could not be allowed to exist in Paris.

For this reason Galignani's Messenger is a vapid concern. It presents no thoughts to the reader. It is interesting to the Englishman in Paris, because it gathers English news, and presents it in the original language. As there are always a great many Englishmen in Paris, the journal is tolerably well supported. Then, again, the Paris shop-keepers and hotel-owners know very well that the English are among their best customers, and they advertise largely in it. So far as my experience has gone, I have found the Messenger quite unfair to America. It quotes from the worst of American journals, and is sure to parade anything that may be for the disadvantage of American reputation. It also is generally sure of showing by its quotations its sympathy with "the powers that [Pg 46]be." This may all be natural enough, for it is for their interest to stand well with the despot who rules France, but to an American, and a republican, it excites only disgust. At present the Messenger is as good, or nearly so, as any of the French journals, but when the latter had liberty to write as they pleased, the contrast between the French and English press in Paris was ludicrous. In one you had fearless political writing, wit, and spice. In the other, nothing but selections.

Once, while in Paris, during the days of the republic, I called upon the editor of one of the prominent French journals. It was a journal which had again and again paid government fines for the utterance of its honest sentiments, both under Louis Philippe and the presidency of Louis Napoleon. Before the revolution it had a very great influence over the people, and in the days of the so-called republic. The struggle between it and the government, at that time was continued. Its editor's great aim was to express as much truth as was possible and escape the government line, which in the end would suppress the journal.

As I entered the building in which this journal was printed and published, I felt a kind of awe creeping over me, as if coming into the presence of a great mind. We entered the editor's office; a little green baize-covered table by a window, pen and ink, and scissors, indicated the room. One might indeed tremble in such a place. What greater place is there in this world than an editor's office, if his journal be one which sells by tens of thousands and sways a vast number of intelligent men? A throne-room is nothing in comparison to it. Thrones are demolished by the journals. Especially in Paris has such been the case. The liberal press has in past years con[Pg 47]trolled the French people to a wonderful extent. Kings and queens have physical power, but here in this little room was the throne-room of intellect. A door opened out of it into the printing-room, where the thoughts were stamped upon paper, afterward to be impressed upon a hundred thousand minds.

The editor sat over his little desk, an earnest, care-worn, yet hopeful man. His fingers trembled with nervousness, yet his eye was like an eagle's. He did not stir when we first entered, did not even see us, he was so deeply absorbed in what lay before him upon his table. I was glad to watch him for a moment, unobserved. He was no fashionable editor, made no play of his work. He felt the responsibility of his position, and endeavored honestly to do his duty. His forehead was high, his eye black, and his face was very pale. Suddenly he looked up and saw us, and recognized my friend. It was enough that I was a republican, from America, and unlike some Americans, abated not a jot of my radicalism when in foreign countries.

I looked around the room when the first words were spoken, and saw everywhere files of newspapers, old copy and that which was about to be given to the printers. It was very much like an editorial apartment in an American printing office, though in some respects it was different. It was a gloomy apartment, and it seemed to me that the writings of the editor must partake somewhat of the character of the room.

We went into the printing-office, where a hundred hands were setting the "thought-tracks." It seemed as if everyone in the building, from editor-in-chief down to the devil, was solemn with the thought of his high and noble avocation. There was a half sadness on every [Pg 48]countenance, for the future was full of gloom. I was struck with the fact that the office did not seem to me to be a French office. There was a gravity, a solemnity, not often seen in Paris. The usual politeness of a Parisian was there, but no gayety, no recklessness. Anxiety trouble, or fixedness of purpose were written upon almost every countenance. In one corner lay piled up to the ceilings copies of the journal, and I half expected to see a band of the police walk in and seize them. It seemed as if they half expected some such thing, but they worked on without saying a word. I became at that moment convinced that a portion of the French people had been wronged by foreigners. There is a large class who are not only intellectual, but they are earnest and grave. They do not wish change for the sake of it. They love liberty and would die for it. Many of this class were murdered in cold blood by Louis Napoleon. Others were sent to Cayenne, to fall a prey to a climate cruel as the guillotine, or were sent into strange lands to beg their bread. These men were the real glory of France, and yet they were forced to leave it.

I am fond of being at perfect liberty to ramble where my fancy may lead. If the sun shine pleasantly this morning, and I would like to hear the birds sing and smell the flowers, I go to some pleasant garden and indulge my mood. Or, if I am sad, I go to the grave of genius, and lean over the tomb of Abelard and Heloise.

When I lived in Paris, I had no regularity in my wanderings, no method in my sight-seeing, following a perhaps wayward fancy, and enjoying myself the better for it.

One beautiful morning I sauntered out from my hotel, with a friend, who was also a stranger in Paris.

"Where shall we go?" he asked.

"To a little cemetery called Picpus, far away from here."

"Will it be worth our while to go so far to see a small cemetery?"

"You shall see when we get there."

We went part of the way by an omnibus, and walked the rest, and when the morning was nearly spent, we stood before No. 15, Rue de Picpus. The place was once a convent of the order of St. Augustine, but is now occupied by the "Women of the Sacred Heart." Within the convent, which we entered, there is a pretty Doric chapel [Pg 50]with an Ionic portal. There was an air of privacy about, the little chapel which pleased me, and a chasteness in its architecture which could not fail to please any one who loves simple beauty. Within the walls of the court, there is a very small private cemetery, but though private, the porter, if you ask him politely, will let you enter, especially if you tell him you are from America.

"Here is the cemetery which we have come to see," I said to my friend.

"Certainly, it is a very pretty one," he replied; "still I see nothing to justify our coming so far to behold it."

"Wait a little while and you will not say so."

The first group of graves before which we stopped, was that of some victims of the reign of terror—poor slaughtered men and women. The grass was growing pleasantly above them, and all was calm, and sunny, and beautiful around. Perhaps the sun shone as pleasantly when, on the "Place de la Concorde," they walked up the steps of the scaffold to die—for Liberty! Oh shame! One—two—three—four—there were eight graves we counted, all victims of the reign of terror. For a moment I forgot where I was; the graves were now at my feet, but I saw the poor victims go slowly up to their horrible death. The faces of grinning, scowling devils, male and female, were before me, all clamoring for blood. I could see the tiger-thirst for human flesh in every countenance—the fierce eye—the flushed face—and yet, how still were the winds, how cheerful the sky.

Yet, though every pure-hearted man or woman must detest the horrible cruelties of the great revolution must shudder at the bare mention of the names of the leaders in it, is it not an eternal law of God, that oppression at last produces madness? Have not tyrants [Pg 51]this fact always to dream over—though you may escape the vengeance of outraged humanity, yet your children, your children's children shall pay the terrible penalty. Louis XVI. was a gentle king; unwise, but never at heart tyrannical; but alas! he answered not merely for his own misdeeds, but for the misdeeds, the tyrannical conduct of centuries of kingcraft. It was an inevitable consequence—and it will ever be so. But I am moralizing.

"You came to see these graves?" remarked my friend. "They are interesting places to ponder and dream over."

"Not to see these, though, did I come," I replied.

We soon came to the graves of nobility. There was the tomb of a Noailles, a Grammont, a Montagu. Plain, all of them, and yet with an air at once chaste and artistic. There was the tomb of Rosambo and Lemoignon amid the tangled grass. All of these names were once noble and great in France, and as I bent over them, I could but call up France in the days of the ancien régime, when all these names called forth bows and fawnings from the people. Dead and buried nobility—what is it? The nobility goes—names die with the body.

"You came out to see buried nobility," said my companion.

"Me! Did I ever go out of my way to see even buried royalty? Never, unless the ashes had been something more than a mere king. To see the grave of genius or goodness, but not empty, buried names!"

We went on a little farther—to a quiet spot, where the sun shone in warmly, where the grass was mown away short, but where it was green and bright. The song of a plaintive bird just touched our ears—where it was we could not tell, only we heard it. It was a still, beautiful [Pg 52]spot, and there was a grave before us—yet how very plain! A pure, white marble, a simple tomb.

Now my companion asked no questions, but I saw that his lips quivered. The name on the simple tomb was that of

"LAFAYETTE."

Here, away from the noise of the city, amid silence chaste and sweet, without a monument, lie the remains of one of the greatest men of France. Not in Pere la Chaise, amid grandeur and fashion, but in a little private cemetery, with a cluster of extinguished nobles on one side, and a band of victims of the reign of terror on the other!

We sat down beside his tomb, grateful to the dust beneath our feet for the noble assistance which it gave to the sinking "Old Thirteen," when the soul of Lafayette animated it. How vividly were the days of our long struggle before us. We saw Bunker Hill alive with battalions, and Charlestown lay in flames. Step by step we ran over the bitter struggle, with so much power on one side, and on the other such an amount of determination, but after all so many dark and adverse circumstances, so little physical power in comparison with the hosts arrayed against us. It was when the heart of the nation drooped with an accumulation of misfortune, that Lafayette came and turned the balance in the scales. And we were grateful to him; not so much for what he really accomplished, as for what he attempted—for the daring spirit, the noble generosity!

Then, too, I thought how Lafayette stood between the king and the people, before and after the reign of terror—thought of his devotion to France—of his stern patri[Pg 53]otism, which would neither tremble before a king nor an infuriated rabble. Yet he was obliged to fly for life from Paris—from France. He lay in a felon's dungeon in a foreign land, for lack of devotion to kingcraft, and could not return to France because he loved humanity too well. Was it not hard?

France has never been just to her great men. She welcomes to her bosom her most dangerous citizens, and casts out the true and the noble. She did so when she sent Lafayette away. She did so in refusing Lamartine and accepting Louis Napoleon.

When I first visited Paris, while Louis Napoleon was president of the republic instead of emperor, I became acquainted with a young man from America who had lived seventeen years in Paris. He was thoroughly acquainted with every phase of Parisian life, from the highest to the lowest, and knew the principal political characters of the country. He was a thorough radical, and an enthusiast. He came to Paris for an education, and when he had finished it, he had imbibed the most radical opinions respecting human liberty, and as his native town was New Orleans, and his father a wealthy slaveholder, he concluded to remain in Paris. When I found him, he was living in the Latin quarter, among the students, at a cheap, though very neat hotel. He was refined, modest, and highly educated, and was busy in political writing and speculations. At that time he showed me a complete constitution for a "model republic" in France, and [Pg 54]a code of laws fit for Paradise rather than France. The documents exhibited great skill and learning, but the impress of an enthusiast was upon them all. By his conduct or manner, the stranger would never have supposed that my friend was enthusiastic. He never indulged in any flights of indignation at the existing state of things, never was thrown off his guard so as to show by his speech or his manner that he was passionately attached to liberal principles. It was only after I had come to know him well, that I discovered this fact—that he was a great enthusiast, and so deeply attached to the purest principles respecting human freedom and happiness, that he would willingly have died for them. Living in Paris, one of the most dissolute cities of the world, he was pure in his morals, and as rigidly honest as any Puritan in Cromwell's day. But with all his own purity he possessed unbounded charity for others. His friends were among all classes, and were good and bad. One day I saw him walking with one of the most distinguished men of France. A few days after, while he was taking a morning walk, he met a university student with a grisette upon his arm—his mistress. The student wished to leave Paris for the day on business, and asked my friend to accompany his mistress back to their rooms. With the utmost composure and politeness the radical offered his arm, and escorted the frail woman to her apartments.

Of course, this man was carefully watched by the police. He was well known, and the eye of the secret police was constantly upon him. He still clung to his old American passport, for it had repeatedly caused him to be respected when other reasons were insufficient.

I one day wrote a note to a friend in a distant part of the city, and was going to drop it into the post-office [Pg 55]when my friend, who was with me, remonstrated. "You can walk to the spot and deliver it yourself," said he, "and you will have saved the two sous postage. I am going that way; let me have the postage and I will deliver it."

"I will go with you," I said, at the same time giving him the two sous. He took them without any remonstrance. On the way we met a poor old family, singing and begging in the streets. "They must live," said my friend, "and we will give them our mite in partnership." So he added two sous to those I had given him, and tossed them to the beggars. This was genuine charity, given not for ostentation, but to relieve suffering and administer comfort. I found him at all times entirely true to his principles, and became very much interested in him.

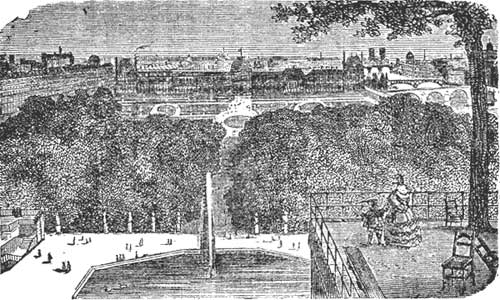

We took a walk together one evening, to hear music in the Luxembourg Gardens. As we approached them, the clock on the old building of the Chamber of Peers struck eight, and at once the band commenced playing some operatic airs of exquisite beauty. Now a gay and enlivening passage was performed, and then a mournful air, or something martial and soul-stirring. The music ceased at nine, and a company of soldiers marched to the drum around the frontiers of the gardens, to notify all who were in it that the gates must soon close.

"What very fine drumming," I said to my companion.

"Yes," he replied, "but you should hear a night rappel. I heard it often in the days of the June fight. One morning I heard it at three o'clock, calling the soldiers together for battle. You cannot know what a thrill of horror it sent through every avenue of this great city. I got up hastily, and dressed myself and ran into the streets. It was not for me to shrink from the conflict. But the alarm [Pg 56]was a false one. Soldiers were in every street, but there was no fighting that day."

A few months before, my friend ventured to publish a pamphlet on the subject of French interference in Italy. He condemned in unequivocal terms the expedition to Italy, and showed how it violated the feelings of the French nation. A few days afterward, he received the following laconic note:

"M. Blank is invited to call on the prefect of the police, at his office, to-morrow, Friday, at eleven o'clock."

M. Blank sat down, first, and wrote an able letter to the minister for the interior, for he well knew that the note signified the suppression of the pamphlet, and very likely his ejection from France. He sent the same letter to the American minister, and the next day answered the summons of the prefect. This is the account of the interview which he gave me from a journal he was in the habit of keeping at that time:

"I read the word 'Réfugiés' over the door, and it reminded me of the inscription on the gates of hell—'Leave all hope far behind.' Everyone knows that the very reason that ghosts are dreaded, is that ghosts were never seen. It is the same for policemen—those 'Finders out of Occasions,' as Othello styles them—those 'rough and ready' to choke ideas, as the bud is bit by the venomous worm 'ere it can spread its sweet leaves to the air.' I was about to encounter the assailing eyes of knavery. A gentleman of the administration welcomed me in. 'Sir,' I said, coldly, 'I was invited to meet the prefect of the police. I wish to know what is deemed an outrage to the established government of France?'

"The reply, was, 'The procureur-general noticed sev[Pg 57]eral portions of your book; sit down and we will read them!'

"I listened to several extracts, where there were allusions to princes, (Louis Napoléon had been formerly a prince, and this was objected to,) and remarked to them that France recognized no princes—that what I had written about the expedition to Italy, I had the right, as a publicist, to write. The world had universally repudiated that expedition, and the president had tacitly done the same in his letter to Colonel Ney, and in dismissing the ministers who planned the expedition. The president being quoted as authority, the agent of the executive thought it useless to hold the argument any longer, and backed out. The gentlemen of the police knew nothing of bush-fighting, and might have exclaimed with the muse in Romeo, 'Is this poultice for my aching bones?'"

The upshot of the examination was, that the pamphlet was untouched, and M. Blank remained in Paris.

But he was watched closer than ever. When I left him, he was waiting in daily expectation of a coup de état on the part of Louis Napoléon. I asked him what hopes there were for France. He shook his head sadly—he despaired of success. It might be that Napoléon would be beaten down by the populace, if he attempted to erect a throne, but he had faint hopes of it, for he had got the army almost completely under his influence. Or it was possible that Napoléon might not violate his solemn oaths to support the republic—not for lack of disposition, but fearing the people. I could see, however, that my friend had little faith in the immediate future of "poor France," as he called her, as if she were his mother. He thought the reason why the republic would be overthrown, was from the conduct of those who had been at its head in [Pg 58]the early part of its history. The republicans, soon after Louis Philippe's flight, acted, he thought, with great weakness. If strong men had been at the helm, then no such man as Louis Napoléon would have been allowed afterward to take the presidential chair. I think he was more right than wrong. A vigorous and not too radical administration, might have preserved the republic for years—possibly for all time. Louis Napoléon should not have been allowed to enter France, nor any like him, who had proved themselves disturbers of the peace.

About a year after the time I have been describing, while walking down Nassau street, in New York, I very suddenly and unexpectedly met my friend, the radical!

"Aha!" said I, "you have left Paris. Well, you have shown good taste."

"No! no!" he replied, "I did not leave it till Louis Napoléon forced me to choose exile or imprisonment. I had no choice in the matter."

He seemed to feel lost amid the bustle of New York. His dream was over, and at thirty-five he found himself amid the realities of a money-seeking nation. The look upon his face was sad, almost despairing. I certainly never pitied a man more than I did him. Pure, guileless generous—and poor, what could he do in New York?

The summer and autumn are the seasons one should spend in Paris, to see it in its full glory. The people of Paris live out of doors, and to see them in the winter, is not to know them thoroughly. The summer weather is unlike that of London. The air is pure, the sky serene, and the whole city is full of gardens and promenades. The little out-of-door theaters reap harvests of money—the tricksters, the conjurors, the street fiddlers, and all sorts of men who get their subsistence by furnishing the people with cheap amusements, are in high spirits, for in these seasons they can drive a fine business. Not so in the winter. Then they are obliged either to wander over the half-deserted places, gathering here and there a sou, or shut themselves up in their garret or cellar apartments, and live upon their summer gains. To the stranger who must be economical, Paris in the winter is not to be desired, for fuel is enormously high in that city. A bit of wood is worth so much cash, and a log which in America would be thrown away, would there be worth a little fortune to a poor wood-dealer.

The country around Paris is scarcely worth a visit in the winter or early spring months, but in the summer it is far different. I remember a little walk I took one day past the fortifications. When I came to the walls of the city, I was obliged to pass through a narrow gate. All who enter the city are inspected, for there is a heavy duty upon provisions of nearly all kinds which are brought from the provinces into Paris. The duty upon wines is very heavy. Upon a bottle of cheap wine, which costs in [Pg 60]the country but fifteen sous, there is a gate-duty of five sous. This is one reason why the poor people of Paris on fête days, crowd to the country villages near Paris. There they can eat and drink at a much cheaper rate than in town, besides having the advantage of pure air and beautiful scenery. I witnessed an amusing sight at this gate. A man was just entering from the country. He was very large in the abdominal regions, so much so that the gate-keeper's suspicions were aroused, and he asked the large traveler a few leading questions. He protested that he was innocent of any attempt to defraud the revenues of Paris. The gate-keeper reached out his hand as if to examine the unoffending man, and he grew very angry. His face assumed a scarlet hue, and his voice was hoarse with passion, probably from the fact that he was sensitive about his obesity. But the gate-keeper saw in his conduct only increased proof of his guilt, and finally insisted upon laying his hand upon the suspicious part, when with a poorly-concealed smile, but a polite "beg your pardon," he let the man pass on his way. It is probable the gate-keeper was more rigid in his examinations, from the fact that not long before a curious case of deception had occurred at one of the other gates, or rather a case of long-continued deception was exposed. A man who lived in a little village just outside of the walls, became afflicted with the dropsy in the abdominal regions. He then commenced the business of furnishing a certain hotel in Paris with fresh provisions, and for this purpose he visited it twice a day with a large basket on his head or arm. The basket, of course, was always duly examined, and the man passed through. He became well-known to the gate-keeper, and thus weeks and months passed away, until one day the keeper was sure he smelt brandy, and [Pg 61]searched the basket more carefully than usual. Nothing was discovered, but the fragrance of the brandy grew stronger, and his suspicions were directed to the man. He was examined, and it was found that his dropsy could easily be cured, for it consisted in wearing something around his body which would contain several gallons, for the man was really small in size, though tall, and he had made it his business to carry in liquors to the city, and evade the taxes. But at last, unfortunately, the portable canteen sprung a leak, and this was the cause which led to the discovery.

At another gate, a woman was detected in carrying quantities of brandy under her petticoats, and only passing for a large woman. I knew of a woman who, in passing the Liverpool custom house, sewed cigars to a great number into her skirt, but was, to her great chagrin, detected, and also to the dismay of her husband, whom she intended to benefit.

Such taxes would not be endured in any American city, but the old world is used to taxation. In the very out-skirts of London there are toll-gates in the busiest of streets, but that is not so bad as the local tariff system.

I soon came, in my walk, to the fortifications of Paris. They were constructed by Louis Phillippe, and are magnificent works of defense. There is one peculiar feature of this chain of defense which has excited a great deal of remark. It is quite evident that a part of the fortifications were constructed with a view to defend one's self from enemies within, as well as without. Louis Phillippe evidently remembered the past history of Paris, and felt the possibility of a future in which he might like to have the command of Paris with his guns, as well as an enemy outside the wall. But the fortifications and the cannon [Pg 62]were of no manner of use to him. So, very possibly, the grand army which Louis Napoleon has raised may be of no use to him, and the little prince, the young king of Algeria, may end his days a wanderer in the United States, as his father was before him. It is to be hoped, if he does, that he will pay his bills.

The fortifications of Paris extend entirely around the city, and are seventeen miles in length. I went to the top of them, but I had not stood there five minutes before the soldiers warned me off. The approach to the city side of the wall is very gradual, by means of a grass-covered bank. While standing upon the summit, a train of cars—came whizzing along at a fine rate. I saw for the first time people riding on the tops of cars as on a coach. The train was bound to Versailles, and as the distance is short, and probably the speed attained not great, seats are attached to the tops of the cars, and for a very small sum the poorer classes can ride in them. In fine weather it is said that this kind of riding is very pleasant.

I passed out through the gates beyond the fortifications, and was in the open country—among the trees, the birds and flowers, and the cultivated fields. The contrast between what I saw and the city, was great. Here, all was beautiful nature. There, all that is grand and exquisite in art. The fields around me were green with leaves and plants; the branches of the trees swayed to and fro in the restless breeze; the little peasant huts had a picturesque appearance in the distance, and the laborers at work seemed more healthy than the artisans of Paris. I approached a peasant who was following the plow. I was surprised to find the plow he used to be altogether too heavy for the use to which it was put. Yet I was in sight of Paris, the city of the arts and sciences. Such a plow [Pg 63]could not have been found in all New England. I looked at the man, too, and compared him with an American farmer or native workman. He was miserably dressed, and wore shoes which might have been made in the twelfth century. He had no look of intelligence upon his face, but stared at me with a dull and idiotic eye. This was the peasant under the walls of Paris—what must he be in the provincial forests?

Leaving the plowman, I walked on, following a pretty little road, until I came to a large flock of sheep in the care of a shepherd-boy and a dog. While I stood looking at them, the boy started them off across the fields and through the lawns to some other place. All that he did was to follow the sheep, but I certainly never saw a dog so capable and intelligent as that one. He seemed to catch from his master the idea of their destination at once, and kept continually running around the flock, now stirring them into a faster gait, then heading off some wayward fellow who manifested a strong disposition to sheer off to the right or left, and again turning the whole body just where the master wished. It was an amusing sight, and well worth the walk from the city. To be sure, the dog was rather egotistical and ostentatious. He knew his smartness, and was quite willing that bystanders should know it too, for he pawed, and fawned, and barked at a tremendous rate. The flock seemed to know his ways, and while they obeyed his voice, they were not particularly frightened at it.

Leaving the flock and their master, I soon came to a little inn, and sat down to dine. It was not much like the restaurants on the Boulevard, or even like those within the city on retired streets, but I got a very comfortable meal, and for a very small sum of money. I found that [Pg 64]the mere mention that I was an American, in all such places as this, insured me polite attention, and I could often notice, instantly, the change of manners after I had informed my entertainers of my country. It is but a slight fact from which to draw an inference, but yet I could not help inferring that the more intelligent of the common people of Paris are yet, notwithstanding the despotism which hovers over France, in their secret hearts longing for the freedom of a just republic.