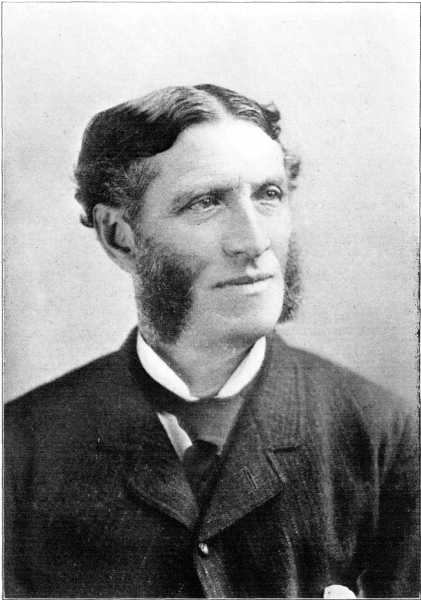

Matthew Arnold

From a Photograph by Sarony

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Matthew Arnold, by G. W. E. Russell This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Matthew Arnold Author: G. W. E. Russell Release Date: September 25, 2005 [EBook #16745] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MATTHEW ARNOLD *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Taavi Kalju and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

MATTHEW ARNOLD. By G.W.E. Russell.

CARDINAL NEWMAN. By William Barry, D.D.

MRS. GASKELL. By Flora Masson.

JOHN BUNYAN. By W. Hale White.

CHARLOTTE BRONTË. By Clement K. Shorter.

R.M. HUTTON. By W. Robertson Nicoll.

GOETHE. By Edward Dowden.

HAZLITT. By Louise Imogen Guiney.

"We see him wise, just, self-governed, tender, thankful, blameless, yet with all this agitated, stretching out his arms for something beyond—tendentemque manus ripæ ulterioris amore."—Essays in Criticism.

It may be thought that some apology is needed for the production of yet another book about Matthew Arnold. If so, that apology is to be found in the fact that nothing has yet been written which covers exactly the ground assigned to me in the present volume.

It was Arnold's express wish that he should not be made the subject of a Biography. This rendered it impossible to produce the sort of book by which an eminent man is usually commemorated—at once a history of his life, an estimate of his work, and an analysis of his character and opinions. But though a Biography was forbidden, Arnold's family felt sure that he would not have objected to the publication of a selection from his correspondence; and it became my happy task to collect, and in some sense to edit, the two volumes of his Letters which were published in 1895. Yet in reality my functions were little more than those of the collector and the annoPg viiitator. Most of the Letters had been severely edited before they came into my hands, and the process was repeated when they were in proof.

A comparison of the letters addressed to Mr. John Morley and Mr. Wyndham Slade with those addressed to the older members of the Arnold family will suggest to a careful reader the nature and extent of the excisions to which the bulk of the correspondence was subjected. The result was a curious obscuration of some of Arnold's most characteristic traits—such, for example, as his over-flowing gaiety, and his love of what our fathers called Raillery. And, in even more important respects than these, an erroneous impression was created by the suppression of what was thought too personal for publication. Thus I remember to have read, in some one's criticism of the Letters, that Mr. Arnold appeared to have loved his parents, brothers, sisters, and children, but not to have cared so much for his wife. To any one who knew the beauty of that life-long honeymoon, the criticism is almost too absurd to write down. And yet it not unfairly represents the impression created by a too liberal use of the effacing pencil.

But still, the Letters, with all their editorialPg ix shortcomings (of which I willingly take my full share) constitute the nearest approach to a narrative of Arnold's life which can, consistently with his wishes, be given to the world; and the ground so covered will not be retraversed here. All that literary criticism can do for the honour of his prose and verse has been done already: conscientiously by Mr. Saintsbury, affectionately and sympathetically by Mr. Herbert Paul, and with varying competence and skill by a host of minor critics. But in preparing this book I have been careful not to re-read what more accomplished pens than mine have written; for I wished my judgment to be, as far as possible, unbiassed by previous verdicts.

I do not aim at a criticism of the verbal medium through which a great Master uttered his heart and mind; but rather at a survey of the effect which he produced on the thought and action of his age.

To the late Professor Palgrave, to Monsieur Fontanès, and to Miss Rose Kingsley my thanks have been already paid for the use of some of Arnold's letters which are published now for the first time. It may be well to state that whenever, in the ensuing pages, passages are put in invertedPg x commas, they are quoted from Arnold, unless some other authorship is indicated. Here and there I have borrowed from previous writings of my own, grounding myself on the principle so well enounced by Mr. John Morley—"that a man may once say a thing as he would have it said, δὶς δὲ οὑκ ἑνδέχεται—he cannot say it twice."

G.W.E.R.

Christmas, 1903.

| PAGE | |

| PREFACE | vii |

| CONTENTS | xi |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | xiii |

| MATTHEW ARNOLD | xv |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Method | 17 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Education | 48 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Society | 111 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Conduct | 172 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Theology | 210 |

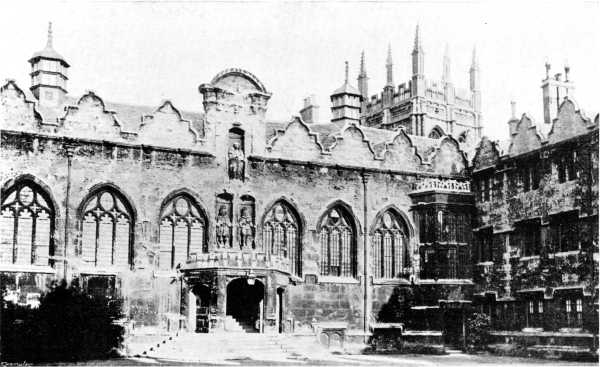

Eldest son of Thomas Arnold, D.D., and Mary Penrose

| Born | 1822 |

| Entered Winchester College | 1836 |

| Transferred to Rugby School | 1837 |

| Scholar of Balliol | 1840 |

| Entered Balliol College | 1841 |

| Newdigate Prizeman | 1843 |

| B.A. | 1844 |

| Fellow of Oriel | 1845 |

| Private Secretary to Lord Lansdowne | 1847 |

| Inspector of Schools | 1851 |

| Married Frances Lucy Wightman | 1851 |

| Professor of Poetry at Oxford | 1857 |

| D.C.L. | 1870 |

| Resigned Inspectorship | 1886 |

| Died | 1888 |

This book is intended to deal with substance rather than with form. But, in estimating the work of a teacher who taught exclusively with the pen, it would be perverse to disregard entirely the qualities of the writing which so penetrated and coloured the intellectual life of the Victorian age. Some cursory estimate of Arnold's powers in prose and verse must therefore be attempted, before we pass on to consider the practical effect which those powers enabled him to produce.

And here it behoves a loyal and grateful disciple to guard himself sedulously against the peril of overstatement. For to the unerring taste, the sane and sober judgment, of the Master, unrestrained and inappropriate praise would have been peculiarly distressing.

This caution applies with special force to our estimate of his rank in poetry. That he was a poet, the most exacting, the most paradoxical criticism will hardly deny; but there is urgent need for moderation and self-control when we come to conPg 2sider his place among the poets. Are we to call him a great poet? The answer must be carefully pondered.

In the first place, he did not write very much. The total body of his poetry is small. He wrote in the rare leisure-hours of an exacting profession, and he wrote only in the early part of his life. In later years he seemed to feel that the "ancient fount of inspiration"[1] was dry. He had delivered his message to his generation, and wisely avoided last words. Then it seems indisputable that he wrote with difficulty. His poetry has little ease, fluency, or spontaneous movement. In every line it bears traces of the laborious file. He had the poet's heart and mind, but they did not readily express themselves in the poetic medium. He longed for poetic utterance, as his only adequate vent, and sought it earnestly with tears. Often he achieved it, but not seldom he left the impression of frustrated and disappointing effort, rather than of easy mastery and sure attainment.

Again, if we bear in mind Milton's threefold canon, we must admit that his poetry lacks three great elements of power. He is not Simple, Sensuous, or Passionate. He is too essentially modern to be really simple. He is the product of a high-strung civilization, and all its complicated crossPg 3currents of thought and feeling stir and perplex his verse. Simplicity of style indeed he constantly aims at, and, by the aid of a fastidious culture, secures. But his simplicity is, to use the distinction which he himself imported from France, rather akin to simplesse than to simplicité—to the elaborated and artificial semblance than to the genuine quality. He is not sensuous except in so far as the most refined and delicate appreciation of nature in all her forms and phases can be said to constitute a sensuous enjoyment. And then, again, he is pre-eminently not passionate. He is calm, balanced, self-controlled, sane, austere. The very qualities which are his characteristic glory make passion impossible.

Another hindrance to his title as a great poet, is that he is not, and never could be, a poet of the multitude. His verse lacks all popular fibre. It is the delight of scholars, of philosophers, of men who live by silent introspection or quiet communing with nature. But it is altogether remote from the stir and stress of popular life and struggle. Then, again, his tone is profoundly, though not morbidly, melancholy, and this is fatal to popularity. As he himself said, "The life of the people is such that in literature they require joy." But not only his thought, his very style, is anti-popular. Much of his most elaborate work isPg 4 in blank verse, and that in itself is a heavy draw-back. Much also is in exotic and unaccustomed metres, which to the great bulk of English readers must always be more of a discipline than of a delight. And, even when he wrote in our indigenous metres, his ear often played him false. His rhymes are sometimes only true to the eye, and his lines are over-crowded with jerking monosyllables. Let one glaring instance suffice—

The sentiment is true and even profound; but the expression is surely rugged and jolting to the last degree; and there are many lines nearly as ineuphonious. Here are some samples, collected by that fastidious critic, Mr. Frederic Harrison—

These Mr. Harrison cites as proof that, "where Nature has withheld the ear for music, no labour and no art can supply the want." And I think that even a lover may add to the collection—

But, after all these deductions and qualifications have been made, it remains true that Arnold wasPg 5 a poet, and that his poetic quality was pure and rare. His musings "on Man, on Nature, and on Human Life,"[2] are essentially and profoundly poetical. They have indeed a tragic inspiration. He is deeply imbued by the sense that human existence, at its best, is inadequate and disappointing. He feels, and submits to, its incompleteness and its limitations. With stately resignation he accepts the common fate, and turns a glance of calm disdain on all endeavours after a spurious consolation. All round him he sees

He dismissed with a rather excessive contempt the idea that the dreams of childhood may be intimations of immortality; and the inspiration which poets of all ages have agreed to seek in the hope of endless renovation, he found in the immediate contemplation of present good. What his brother-poet called "self-reverence, self-knowledge, self-control," are the keynotes of that portion of his poetry which deals with the problems of human existence. When he handles these themes, he speaks to the innermost consciousness of his hearers, telling us what we know about ourselves, and have believed hidden from all others, or else putting into words of perfect suitableness what wePg 6 have dimly felt, and have striven in vain to utter. It is then that, to use his own word, he is most "interpretative." It is this quality which makes such poems as Youth's Agitations, Youth and Calm, Self-dependence, and The Grande Chartreuse so precious a part of our intellectual heritage.

In 1873 he wrote to his sister: "I have a curious letter from the State of Maine in America, from a young man who wished to tell me that a friend of his, lately dead, had been especially fond of my poem, A Wish, and often had it read to him in his last illness. They were both of a class too poor to buy books, and had met with the poem in a newspaper."

It will be remembered that in A Wish, the poet, contemptuously discarding the conventional consolations of a death-bed, entreats his friends to place him at the open window, that he may see yet once again—

This solemn love and reverence for the continuous life of the physical universe may remind us that Arnold's teaching about humanity, subtle and searching as it is, has done less to endear him to many of his disciples, than his feeling for Nature. His is the kind of Nature-worship which takes nothing at second-hand. He paid "the Mighty Mother" the only homage which is worthy of her acceptance, a minute and dutiful study of her moods and methods. He placed himself as a reverent learner at her feet before he presumed to go forth to the world as an exponent of her teaching. It is this exactness of observation which makes his touches of local colouring so vivid and so true. This gives its winning charm to hisPg 8 landscape-painting, whether the scene is laid in Kensington Gardens, or the Alps, or the valley of the Thames. This fills The Scholar-Gipsy, and Thyrsis, and Obermann, and The Forsaken Merman with flawless gems of natural description, and felicities of phrase which haunt the grateful memory.

In brief, it seems to me that he was not a great poet, for he lacked the gifts which sway the multitude, and compel the attention of mankind. But he was a true poet, rich in those qualities which make the loved and trusted teacher of a chosen few—as he himself would have said, of "the Remnant." Often in point of beauty and effectiveness, always in his purity and elevation, he is worthy to be associated with the noblest names of all. Alone among his contemporaries, we can venture to say of him that he was not only of the school, but of the lineage, of Wordsworth. His own judgment on his place among the modern poets was thus given in a letter of 1869: "My poems represent, on the whole, the main movement of mind of the last quarter of a century, and thus they will probably have their day as people become conscious to themselves of what that movement of mind is, and interested in the literary productions which reflect it. It might be fairly urged that I have less poetic sentiment than Tennyson,Pg 9 and less intellectual vigour and abundance than Browning. Yet because I have more perhaps of a fusion of the two than either of them, and have more regularly applied that fusion to the main line of modern development, I am likely enough to have my turn, as they have had theirs."

When we come to consider him as a prose-writer, cautions and qualifications are much less necessary. Whatever may be thought of the substance of his writings, it surely must be admitted that he was a great master of style. And his style was altogether his own. In the last year of his life he said to the present writer: "People think I can teach them style. What stuff it all is! Have something to say, and say it as clearly as you can. That is the only secret of style."

Clearness is indeed his own most conspicuous note, and to clearness he added singular grace, great skill in phrase-making, great aptitude for beautiful description, perfect naturalness, absolute ease. The very faults which the lovers of a more pompous rhetoric profess to detect in his writing are the easy-going fashions of a man who wrote as he talked. The members of a college which produced Cardinal Newman, Dean Church, and Matthew Arnold are not without some justification when they boast of "the Oriel style."

But style, though a great delight and a greatPg 10 power, is not everything, and we must not found our claim for him as a prose-writer on style alone. His style was the worthy and the suitable vehicle of much of the very best criticism which English literature contains. We take the whole mass of his critical writing, from the Lectures on Homer and the Essays in Criticism down to the Preface to Wordsworth and the Discourse on Milton; and we ask, Is there anything better?

When he wrote as a critic of books, his taste, his temper, his judgment were pretty nearly infallible. He combined a loyal and reasonable submission to literary authority with a free and even daring use of private judgment. His admiration for the acknowledged masters of human utterance—Homer, Sophocles, Shakespeare, Milton, Goethe—was genuine and enthusiastic, and incomparably better informed than that of some more conventional critics. Yet this cordial submission to recognized authority, this honest loyalty to established reputation, did not blind him to defects, did not seduce him into indiscriminate praise, did not deter him from exposing the tendency to verbiage in Burke and Jeremy Taylor, the excessive blankness of much of Wordsworth's blank verse, the undercurrent of mediocrity in Macaulay, the absurdities of Ruskin's etymology. And, as in great matters, so in small. Whatever literary production wasPg 11 brought under his notice, his judgment was clear, sympathetic, and independent. He had the readiest appreciation of true excellence, a quick eye for minor merits of facility and method, a severe intolerance of turgidity and inflation—of what he called "desperate endeavours to render a platitude endurable by making it pompous," and a lively horror of affectation and unreality. These, in literature as in life, were in his eyes the unpardonable sins.

On the whole it may be said that, as a critic of books, he had in his lifetime the reputation, the vogue, which he deserved. But his criticism in other fields has hardly been appreciated at its proper value. Certainly his politics were rather fantastic. They were influenced by his father's fiery but limited Liberalism, by the abstract speculation which flourishes perennially at Oxford, and by the cultivated Whiggery which he imbibed as Lord Lansdowne's Private Secretary; and the result often seemed wayward and whimsical. Of this he was himself in some degree aware. At any rate he knew perfectly that his politics were lightly esteemed by politicians, and, half jokingly, half seriously, he used to account for the fact by that jealousy of an outsider's interference, which is natural to all professional men. Yet he had the keenest interest, not only in the deeper problemsPg 12 of politics, but also in the routine and mechanism of the business. He enjoyed a good debate, liked political society, and was interested in the personalities, the trivialities, the individual and domestic ins-and-outs, which make so large a part of political conversation.

But, after all, Politics, in the technical sense, did not afford a suitable field for his peculiar gifts. It was when he came to the criticism of national life that the hand of the master was felt. In all questions affecting national character and tendency, the development of civilization, public manners, morals, habits, idiosyncrasies, the influence of institutions, of education, of literature, his insight was penetrating, his point of view perfectly original, and his judgment, if not always sound, invariably suggestive. These qualities, among others, gave to such books as Essays in Criticism, Friendship's Garland, and Culture and Anarchy, an interest and a value quite independent of their literary merit. And they are displayed in their most serious and deliberate form, dissociated from all mere fun and vivacity, in his Discourses in America. This, he told the present writer, was the book by which, of all his prose-writings, he most desired to be remembered. It was a curious and memorable choice.

Another point of great importance in his prosePg 13writing is this; if he had never written prose the world would never have known him as a humorist. And that would have been an intellectual loss not easily estimated. How pure, how delicate, yet how natural and spontaneous his humour was, his friends and associates knew well; and—what is by no means always the case—the humour of his writing was of exactly the same tone and quality as the humour of his conversation. It lost nothing in the process of transplantation. As he himself was fond of saying, he was not a popular writer, and he was never less popular than in his humorous vein. In his fun there is no grinning through a horse-collar, no standing on one's head, none of the guffaws, and antics, and "full-bodied gaiety of our English Cider-Cellar." But there is a keen eye for subtle absurdity, a glance which unveils affectation and penetrates bombast, the most delicate sense of incongruity, the liveliest disrelish for all the moral and intellectual qualities which constitute the Bore, and a vein of personal raillery as refined as it is pungent. Sydney Smith spoke of Sir James Mackintosh as "abating and dissolving pompous gentlemen with the most successful ridicule." The words not inaptly describe Arnold's method of handling personal and literary pretentiousness.

His praise as a phrase-maker is in all thePg 14 Churches of literature. It was his skill in this respect which elicited the liveliest compliments from a transcendent performer in the same field. In 1881 he wrote to his sister: "On Friday night I had a long talk with Lord Beaconsfield. He ended by declaring that I was the only living Englishman who had become a classic in his own lifetime. The fact is that what I have done in establishing a number of current phrases, such as Philistinism, Sweetness and Light, and all that is just the thing to strike him." In 1884 he wrote from America about his phrase, The Remnant—"That term is going the round of the United States, and I understand what Dizzy meant when he said that I had performed 'a great achievement in launching phrases.'" But his wise epigrams and compendious sentences about books and life, admirable in themselves, will hardly recall the true man to the recollection of his friends so effectually as his sketch of the English Academy, disturbed by a "flight of Corinthian leading articles, and an irruption of Mr. G.A. Sala;" his comparison of Miss Cobbe's new religion to the British College of Health; his parallel between Phidias' statue of the Olympian Zeus and Coles' truss-manufactory; Sir William Harcourt's attempt to "develop a system of unsectarian religion from the Life of Mr. Pickwick;" the "portlyPg 15 jeweller from Cheapside," with his "passionate, absorbing, almost blood-thirsty clinging to life;" the grandiose war-correspondence of the Times, and "old Russell's guns getting a little honey-combed;" Lord Lumpington's subjection to "the grand, old, fortifying, classical curriculum," and the "feat of mental gymnastics" by which he obtained his degree; the Rev. Esau Hittall's "longs and shorts about the Calydonian Boar, which were not bad;" the agitation of the Paris Correspondent of the Daily Telegraph on hearing the word "delicacy"; the "bold, bad men, the haunters of Social Science Congresses," who declaim "a sweet union of philosophy and poetry" from Wordsworth on the duty of the State towards education; the impecunious author "commercing with the stars" in Grub Street, reading "the Star for wisdom and charity, the Telegraph for taste and style," and looking for the letter from the Literary Fund, "enclosing half-a-crown, the promise of my dinner at Christmas, and the kind wishes of Lord Stanhope[3] for my better success in authorship."

One is tempted to prolong this analysis of literary arts and graces; but enough has been said to recall some leading characteristics of Arnold'sPg 16 genius in verse and prose. We turn now to our investigation of what he accomplished. The field which he included in his purview was wide—almost as wide as our national life. We will consider, one by one, the various departments of it in which his influence was most distinctly felt; but first of all a word must be said about his Method.

The Matthew Arnold whom we know begins in 1848; and, when we first make his acquaintance, in his earliest letters to his mother and his eldest sister, he is already a Critic. He is only twenty-five years old, and he is writing in the year of Revolution. Thrones are going down with a crash all over Europe; the voices of triumphant freedom are in the air; the long-deferred millennium of peace and brotherhood seems to be just on the eve of realization. But, amid all this glorious hurly-burly, this "joy of eventful living," the young philosopher stands calm and unshaken; interested indeed, and to some extent sympathetic, but wholly detached and impartially critical. He thinks that the fall of the French Monarchy is likely to produce social changes here, for "no one looks on, seeing his neighbour mending, without asking himself if he cannot mend in the same way." He is convinced that "the hour of the hereditary peerage and eldest sonship and immense properties has struck"; he thinks that a five years' continuancePg 18 of these institutions is "long enough, certainly, for patience, already at death's door, to have to die in." He pities (in a sonnet) "the armies of the homeless and unfed." But all the time he resents the "hot, dizzy trash which people are talking" about the Revolution. He sees a torrent of American vulgarity and "laideur" threatening to overflow Europe. He thinks England, as it is, "not liveable-in," but is convinced that a Government of Chartists would not mend matters; and, after telling a Republican friend that "God knows it, I am with you," he thus qualifies his sympathy—

In fine, he is critical of his own country, critical of all foreign nations, critical of existing institutions, critical of well-meant but uninstructed attempts to set them right. And, as he was in the beginning, so he continued throughout his life and to its close. It is impossible to conceive of him as an enthusiastic and unqualified partisan of any cause, creed, party, society, or system. Admiration he had, for worthy objects, in abundant store; high appreciation for what was excellent; sympathy with all sincere and upward-tending endeavour.Pg 19 But few indeed were the objects which he found wholly admirable, and keen was his eye for the flaws and foibles which war against absolute perfection. On the last day of his life he said in a note to the present writer: "S—— has written a letter full of shriekings and cursings about my innocent article; the Americans will get their notion of it from that, and I shall never be able to enter America again." That "innocent article" was an estimate, based on his experience in two recent visits to the United States, of American civilization. "Innocent" perhaps it was, but it was essentially critical. He began by saying that in America the "political and social problem" had been well solved; that there the constitution and government were to the people as well-fitting clothes to a man; that there was a closer union between classes there than elsewhere, and a more "homogeneous" nation. But then he went on to say that, besides the political and social problem, there was a "human problem," and that in trying to solve this America had been less successful—indeed, very unsuccessful. The "human problem" was the problem of civilization, and civilization meant "humanization in society"—the development of the best in man, in and by a social system. And here he pronounced America defective. America generally—life, people, possessions—was not "interesting." AmeriPg 20cans lived willingly in places called by such names as Briggsville, Jacksonville and Marcellus. The general tendency of public opinion was against distinction. America offered no satisfaction to the sense for beauty, the sense for elevation. Tall talk and self-glorification were rampant, and no criticism was tolerated. In fine, there were many countries, less free and less prosperous, which were more civilized.

That "innocent article," written in 1888, shows exactly the same balanced tone and temper—the same critical attitude towards things with which in the main he sympathizes—as the letters of 1848.

And what is true of the beginning and the end is true of the long tract which lay between. From first to last he was a Critic—a calm and impartial judge, a serene distributer of praise and blame—never a zealot, never a prophet, never an advocate, never a dealer in that "blague and mob-pleasing" of which he truly said that it "is a real talent and tempts many men to apostasy."

For some forty years he taught his fellow-men, and all his teaching was conveyed through the critical medium. He never dogmatized, preached, or laid down the law. Some great masters have taught by passionate glorification of favourite personalities or ideals, passionate denunciation of what they disliked or despised. Not such wasPg 21 Arnold's method; he himself described it, most happily, as "sinuous, easy, unpolemical." By his free yet courteous handling of subjects the most august and conventions the most respectable, he won to his side a band of disciples who had been repelled by the brutality and cocksureness of more boisterous teachers. He was as temperate in eulogy as in condemnation; he could hint a virtue and hesitate a liking.[4]

It happens, as we have just seen, that his earliest and latest criticisms were criticisms of Institutions, and a great part of his critical writing deals with similar topics; but these will be more conveniently considered when we come to estimate his effect on Society and Politics. That effect will perhaps be found to have been more considerable than his contemporaries imagined; for, though it became a convention to praise his literary performances and judgments, it was no less a convention to dismiss as visionary and absurd whatever he wrote about the State and the Community.

But in the meantime we must say a word about his critical method when applied to Life, and when applied to Books. When one speaks of criticism, one is generally thinking of prose. But, when we speak of Arnold's criticism, it is necessary to widen the scope of one's observation; for he was never more essentially the critic than when he concealedPg 22 the true character of his method in the guise of poetry. Even if we decline to accept his strange judgment that all poetry "is at bottom a criticism of life," still we must perceive that, as a matter of fact, many of his own poems are as essentially critical as his Essays or his Lectures.

We all remember that he poked fun at those misguided Wordsworthians who seek to glorify their master by claiming for him an "ethical system as distinctive and capable of exposition as Bishop Butler's," and "a scientific system of thought." But surely we find in his own poetry a sustained doctrine of self-mastery, duty, and pursuit of truth, which is essentially ethical, and, in its form, as nearly "scientific" and systematic as the nature of poetry permits. And this doctrine is conveyed, not by positive, hortatory, or didactic methods, but by Criticism—the calm praise of what commends itself to his judgment, the gentle but decisive rebuke of whatever offends or darkens or misleads. Of him it may be truly said, as he said of Goethe, that

His deepest conviction about "the suffering human race" would seem to have been that itsPg 23 worst miseries arise from a too exalted estimate of its capacities. Men are perpetually disappointed and disillusioned because they expect too much from human life and human nature, and persuade themselves that their experience, here and hereafter, will be, not what they have any reasonable grounds for expecting, but what they imagine or desire. The true philosophy is that which

Wordsworth thought it a boon to "feel that we are greater than we know": Arnold thought it a misfortune. Wordsworth drew from the shadowy impressions of the past the most splendid intimations of the future. Against such vain imaginings Arnold set, in prose, the "inexorable sentence" in which Butler warned us to eschew pleasant self-deception; and, in verse, the persistent question—

He rebuked

He taught that there are

He warned discontented youth not to expect greater happiness from advancing years, because

Friendship is a broken reed, for

and even Hope is buried with the "faces that smiled and fled."

Death, at least in some of its aspects, seemed to him the

And yet, in gleams of happier insight, he saw the man who "flagged not in this earthly strife,"

mount, though hardly, to eternal life. And, as he mused over his father's grave, the conviction forced itself upon his mind that somewhere in the "labour-house of being" there still was employment for that father's strength, "zealous, beneficent, firm."

Here indeed is the more cheerful aspect of his "criticism of life." Such happiness as man is capable of enjoying is conditioned by a frank recognition of his weaknesses and limitations; butPg 25 it requires also for its fulfilment the sedulous and dutiful employment of such powers and opportunities as he has.

First and foremost, he must realize the "majestic unity" of his nature, and not attempt by morbid introspection to dissect himself into

Then he must learn that

He must live by his own light, and let earth live by hers. The forces of nature are to be in this respect his teachers—

But, though he is to learn from Nature and love Nature and enjoy Nature, he is to remember that she

and so he is not to expect too much from her, or demand impossible boons. Still less is he to bePg 26 content with feeling himself "in harmony" with her; for

That "more" is Conscience and the Moral Sense.

And this brings us to the idea of Duty as set forth in his poems, and Duty resolves itself into three main elements: Truth—Work—Love. Truth comes first. Man's prime duty is to know things as they are. Truth can only be attained by light, and light he must cultivate, he must worship. Arnold's highest praise for a lost friend is that he was "a child of light"; that he had "truth without alloy,"

The saddest part of that friend's death is the fear that it may bring,

the best hope for the future, that light will return and banish the follies, sophistries, delusions, which have accumulated in the darkness. "Lucidity of soul" may be—nay, must be, "sad"; but it is not less imperative. And the truth which light revealsPg 27 must not only be sought earnestly and cherished carefully, but even, when the cause demands it, championed strenuously. The voices of conflict, the joy of battle, the "garments rolled in blood," the "burning and fuel of fire" have little place in Arnold's poetry. But once at any rate he bursts into a strain so passionate, so combatant, that it is difficult for a disciple to recognize his voice; and then the motive is a summons to a last charge for Truth and Light—

But the note of battle, even for what he holds dearest and most sacred, is not a familiar note in his poetry. He had no natural love of

His criticism of life sets a higher value on work than on fighting. "Toil unsevered from tranquillity," "Labour, accomplish'd in repose"—is his ideal of happiness and duty.

Even the Duke of Wellington—surely an unpromising subject for poetic eulogy—is praised because he was a worker,

Nature, again, is called in to teach us the secret of successful labour. Her forces are incessantly at work, and in that work they are entirely concentrated—

But those who had the happiness of knowing Arnold in the flesh will feel that they never so clearly recognize his natural voice as when, by his criticism of life, he is inculcating the great law of Love. Even in the swirl of Revolution he clings to his fixed idea of love as duty. After discussing the rise and fall of dynasties, the crimes of diplomacy, the characteristic defects of rival nations, and all the stirring topics of the time, he abruptly concludes his criticism with an appeal to Love. "Be kind to the neighbours—'this is all we can.'"

And as in his prose, so in his poetry. Love, even in arrest of formal justice, is the motive of The Sick King in Bokhara; love, that wipes out sin, of Saint Brandan—

The Neckan and The Forsaken Merman tell the tale of contemptuous unkindness and its enduring poison. A Picture at Newstead depicts the inexpiable evils wrought by violent wrong. Poor Matthias tells in a parable the cruelty, not less real because unconscious, of imperfect sympathy—

In Geist's Grave, the "loving heart," the "patient soul" of the dog-friend are made to "read their homily to man"; and the theme of the homily is still the same: the preciousness of the love which outlives the grave. But nowhere perhaps is his doctrine about the true divinity of love so exquisitely expressed as in The Good Shepherd with the Kid—

So much, then, for his Criticism of Life, as applied in and through his poems. It is not easy to estimate, even approximately, the effect produced by a loved and gifted poet, who for thirty years taught an audience, fit though few, that the main concerns of human life were Truth, Work, and Love. Those "two noblest of things, Sweetness and Light" (though heaven only knows what they meant to Swift), meant to him Love and Truth; and to these he added the third great ideal, Work—patient, persistent, undaunted effort for what a man genuinely believes to be high and beneficent ends. Such a "Criticism of Life," we must all admit, is not unworthy of one who seeks to teach his fellow-men; even though some may doubt whether poetry is the medium best fitted for conveying it.

We must now turn our attention to his performances in the field of literary criticism; and we begin in the year 1853. He had won the prizePg 31 for an English poem at Rugby, and again at Oxford. In 1849 he had published without his name, and had recalled, a thin volume, called The Strayed Reveller, and other Poems. He had done the same with Empedocles on Etna, and other Poems in 1852. The best contents of these two volumes were combined in Poems, 1853, and to this book he gave a Preface, which was his first essay in Literary Criticism. In this essay he enounces a certain doctrine of poetry, and, true to his lifelong practice, he enounces it mainly by criticism of what other people had said. A favourite cry of the time was that Poetry, to be vital and interesting, must "leave the exhausted past, and draw its subjects from matters of present import." It was the favourite theory of Middle Class Liberalism. The Spectator uttered it with characteristic gravity; Kingsley taught it obliquely in Alton Locke. Arnold assailed it as "completely false," as "having a philosophical form and air, but no real basis in fact." In assailing it, he justified his constant recourse to Antiquity for subject and method; he exalted Achilles, Prometheus, Clytemnestra, and Dido as eternally interesting; he asserted that the most famous poems of the nineteenth century "left the reader cold in comparison with the effect produced upon him by the latterPg 32 books of the Iliad, by the Oresteia, or by the episode of Dido." He glorified the Greeks as the "unapproached masters of the grand style." He even ventured to doubt whether the influence of Shakespeare, "the greatest, perhaps, of all poetical names," had been wholly advantageous to the writers of poetry. He weighed Keats in the balance against Sophocles and found him wanting.

Of course, this criticism, so hostile to the current cant of the moment, was endlessly misinterpreted and misunderstood. He thus explained his doctrine in a Preface to a Second Edition of his Poems: "It has been said that I wish to limit the poet, in his choice of subjects, to the period of Greek and Roman antiquity; but it is not so. I only counsel him to choose for his subjects great actions, without regarding to what time they belong." A few years later he wrote to a friend (in a letter hitherto unpublished): "The modern world is the widest and richest material ever offered to the artist; but the moulding and representing power of the artist is not, or has not yet become (in my opinion), commensurate with his material, his mundus representandus. This adequacy of the artist to his world, this command of the latter by him, seems to me to be what constitutes a first-classPg 33 poetic epoch, and to distinguish it from such an epoch as our own; in this sense, the Homeric and Elizabethan poetry seems to me of a superior class to ours, though the world represented by it was far less full and significant."

There is no need to describe in greater detail the two Prefaces, which can be read, among rather incongruous surroundings, in the volume called Irish Essays, and Others. But they are worth noting, because in them, at the age of thirty, he first displayed the peculiar temper in literary criticism which so conspicuously marked him to the end; and that temper happily infected the critical writing of a whole generation; until the Iron Age returned, and the bludgeon was taken down from its shelf, and the scalping-knife refurbished.

In his critical temper, lucidity, courage, and serenity were equally blended. In his criticism of books, as in his criticism of life, he aimed first at Lucidity—at that clear light, uncoloured by prepossession, which should enable him to see things as they really are. In a word, he judged for himself; and, however much his judgment might run counter to prejudice or tradition, he dared to enounce it and persist in it. He spoke with proper contempt of the "tenth-rate critics, for whom any violent shock to the public tastePg 34 would be a temerity not to be risked"; but that temerity he himself had in rich abundance. Homer and Sophocles are the only poets of whom, if my memory serves me, he never wrote a disparaging word. Shakespeare is, and rightly, an object of national worship; yet Arnold ventured to point out his "over-curiousness of expression"; and, where he writes—

Arnold dared to say that the writing was "detestable."

Macaulay is, perhaps less rightly, another object of national worship; yet Arnold denounced the "confident shallowness which makes him so admired by public speakers and leading-article writers, and so intolerable to all searchers for truth"; and frankly avowed that to his mind "a man's power to detect the ring of false metal in the Lays of Ancient Rome was a good measure of his fitness to give an opinion about poetical matters at all." According to Macaulay, Burke was "the greatest man since Shakespeare." Arnold admired Burke, revered him, paid him the highest compliment by trying to apply his ideas to actualPg 35 life; but, when Burke urged his great arguments by obstetrical and pathological illustrations, Arnold was ready to denounce his extravagances, his capriciousness, his lapses from good taste.

The same perfectly courageous criticism, qualifying generous admiration, he applied in turn to Jeremy Taylor and Addison, to Milton, and Pope, and Gray, and Keats, and Shelley, and Scott—to all the principal luminaries of our literary heaven. He went all lengths with Mr. Swinburne in praising Byron's "sincerity and strength," but he qualified the praise: "Our soul had felt him like the thunder's roll," but "he taught us little." Devout Wordsworthian as he is, he does not shrink from saying that much of Wordsworth's work is "quite uninspired, flat and dull," and sets himself to the task of "relieving him from a great deal of the poetical baggage which now encumbers him."

And so Lucidity, which reveals the Truth, enounces its decisions with absolute courage; and to Lucidity and Courage is added the crowning grace of Serenity. However much the subject of his study may offend his taste or sin against his judgment, he never loses his temper with the author whom he is criticising. He never bludgeons or scalps or scarifies; but serenely indicates, with the calm gesture of a superior authority, thePg 36 defects and blots which mar perfection, but which the unthinking multitude ignores, or, at worst, admires.

The years 1860 and 1861 mark an important stage in the development of his critical method. He was now Professor of Poetry at Oxford, and he delivered from the professorial chair his famous lectures On Translating Homer, to which in 1862 he added his "Last Words." As much as anything which he ever wrote, these lectures have a chance of living and being enjoyed when we are dust. For Homer is immortal, and he who interprets Homer to Englishmen may hope at least for a longer life than most of us.

Few are those who can still recall the graceful figure in its silken gown; the gracious address, the slightly supercilious smile, of the Milton jeune et voyageant,[5] just returned from contact with all that was best in French culture to instruct and astonish his own university; few who can still catch the cadence of the opening sentence: "It has more than once been suggested to me that I should translate Homer"; few that heard the fine tribute of the aged scholar,[6] who, as the young lecturer closed a later discourse, murmured to himself, "The Angel ended."

With his characteristic trick of humorous mock-humility, Arnold wrote to a friendly reviewer who praised these lectures on translating Homer: "I am glad any influential person should call attention to the fact that there was some criticism in the three lectures; most people seem to have gathered nothing from them except that I abused F.W. Newman, and liked English hexameters."

Criticisms of criticism are the most melancholy reading in the world, and therefore no attempt will here be made to examine in detail the praise which in these lectures he poured upon the supreme exemplar of pure art, or the delicious ridicule with which he assailed the most respectable attempts to render Homer into English. For the praise, let one quotation suffice—"Homer's grandeur is not the mixed and turbid grandeur of the great poets of the North, of the authors of Othello and Faust; it is a perfect, a lovely grandeur. Certainly his poetry has all the energy and power of the poetry of our ruder climates; but it has, besides, the pure lines of an Ionian horizon, the liquid clearness of an Ionian sky."

On the ridicule, we must dwell a little more at length; for this was, in the modern slang, "a new departure" in his critical method. At the date when he published his lectures On Translating Homer, English criticism of literature was, andPg 38 for some time had been, an extremely solemn business. Much of it had been exceedingly good, for it had been produced by Johnson and Coleridge, and De Quincey and Hazlitt. Much had been atrociously bad, resembling all too closely Mr. Girdle's pamphlet "in sixty-four pages, post octavo, on the character of the Nurse's deceased husband in Romeo and Juliet, with an enquiry whether he had really been a 'merry man' in his lifetime, or whether it was merely his widow's affectionate partiality that induced her so to report him."[7]

But, whether good or bad, criticism had been solemn. Even Arnold's first performances in the art had been as grave as Burke or Wordsworth. But in his lectures On Translating Homer he added a new resource to his critical apparatus. He still pursued Lucidity, Courage, and Serenity; he still praised temperately and blamed humanely; but now he brought to the enforcement of his literary judgment the aid of a delicious playfulness. Cardinal Newman was not ashamed to talk of "chucking" a thing off, or getting into a "scrape." So perhaps a humble disciple may be permitted to say that Arnold pointed his criticisms with "chaff."

This method of depreciating literary performPg 39ances which one dislikes, of conveying dissent from literary doctrines which one considers erroneous, had fallen out of use in our literary criticism. It was least to be expected from a professorial chair in a venerable university—least of all from a professor not yet forty, who might have been expected to be weighed down and solemnized by the greatness of his function and the awfulness of his surroundings. Hence arose the simple and amusing wrath of pedestrian poets like Mr. Ichabod Wright, and ferocious pedants like Professor Francis Newman, and conventional worshippers of such idols as Scott and Macaulay, when they found him poking his seraphic fun at the notion that Homer's song was like "an elegant and simple melody from an African of the Gold Coast," or at lines so purely prosaic as—

or so eccentric as—

or so painful as—

This habit of enlisting playfulness in aid of literary judgment was carried a step further in Essays in Criticism, published in 1865. This book, of which Mr. Paul justly remarks that it was "a great intellectual event," was a collection of essays written in the years 1863 and 1864. The original edition contained a preface dealing very skittishly with Bishop Colenso's biblical aberrations. The allusions to Colenso were wisely omitted from later editions, but the preface as it stands contains (besides the divinely-beautiful eulogy of Oxford) some of Arnold's most delightful humour. He never wrote anything better than his apology to the indignant Mr. Ichabod Wright; his disclaimer of the title of Professor, "which I share with so many distinguished men—Professor Pepper, Professor Anderson, Professor Frickel"; his attempt to comfort the old gentleman who was afraid of being murdered, by reminding him that "il n'y a pas d'homme necessaire"; and in all these cases the humour subserves and advances a serious criticism of books or of life.

As we have now seen him engaged in the duty of criticising others, it will not be out of place to cite in this connection, though they belong to other periods, some criticisms of himself. As far back as 1853, he had observed, with characteristic lucidity, that the great fault of his earlier poemsPg 41 was "the absence of charm." "Charm" was indeed the element in which they were deficient; but, as years advanced, charm was superadded to thought and feeling. In 1867, he said in a letter to his friend F.T. Palgrave: "Saint Beuve has written to me with great interest about the Obermann poem, which he is getting translated. Swinburne fairly took my breath away. I must say the general public praise me in the dubious style in which old Wordsworth used to praise Bernard Barton, James Montgomery, and suchlike; and the writers of poetry, on the other hand—Browning, Swinburne, Lytton—praise me as the general public praises its favourites. This is a curious reversal of the usual order of things. Perhaps it is from an exaggerated estimate of my own unpopularity and obscurity as a poet, but my first impulse is to be astonished at Swinburne's praising me, and to think it an act of generosity. Also he picks passages which I myself should have picked, and which I have not seen other people pick."

In 1869, when the first Collected Edition of his poems was in the press, he wrote to Palgrave, who had suggested some alterations, this estimate of his own merits and defects,—

"I am really very much obliged to you for your letter. I think the printing has made too muchPg 42 progress to allow of dealing with any of the long things now; I have left 'Merope' aside entirely, but the rest I have reprinted. In a succeeding edition, however, I am not at all sure that I shall not leave out the second part of the 'Church of Brou.' With regard to the others, I think I shall let them stand—but often for other reasons than because of their intrinsic merit. For instance, I agree that in the 'Sick King in Bokhara' there is a flatness in parts; but then it was the first thing of mine dear old Clough thoroughly liked. Against 'Tristram,' too, many objections may fairly be urged; but then the subject is a very popular one, and many people will tell you they like it best of anything I have written. All this has to be taken into account. 'Balder' perhaps no one cares much for except myself; but I have always thought, though very likely I am wrong, that it has not had justice done to it; I consider that it has a natural propriety of diction and rhythm which is what we all prize so much in Virgil, and which is not common in English poetry. For instance, Tennyson has in the Idylls something dainty and tourmenté which excludes this natural propriety; and I have myself in 'Sohrab' something, not dainty, but tourmenté and Miltonically ampoullé, which excludes it.... We have enough Scandinavianism in our naturePg 43 and history to make a short conspectus of the Scandinavian mythology admissible. As to the shorter things, the 'Dream' I have struck out. 'One Lesson' I have re-written and banished from its pre-eminence as an introductory piece. 'To Marguerite' (I suppose you mean 'We were apart' and not 'Yes! in the sea') I had paused over, but my instinct was to strike it out, and now your suggestion comes to confirm this instinct, I shall act upon it. The same with 'Second Best.' It is quite true there is a horrid falsetto in some stanzas of the 'Gipsy Child'—it was a very youthful production. I have re-written those stanzas, but am not quite satisfied with the poem even now. 'Shakespeare' I have re-written. 'Cruikshank' I have re-titled, and re-arranged the 'World's Triumphs.' 'Morality' I stick to—and 'Palladium' also. 'Second Best' I strike out and will try to put in 'Modern Sappho' instead—though the metre is not right. In the 'Voice' the falsetto rages too furiously; I can do nothing with it; ditto in 'Stagirius,' which I have struck out. Some half-dozen other things I either have struck out, or think of striking out. 'Hush, not to me at this bitter departing' is one of them. The Preface I omit entirely. 'St. Brandan,' like 'Self-Deception,' is not a piece that at all satisfies me, but I shall let both of them stand."

In 1879 he wrote with reference to the edition of his poems in two volumes—

"In beginning with 'early poems' I followed, as I have done throughout, the chronological arrangement adopted in the last edition, an arrangement which is, on the whole, I think, the most satisfactory. The title of 'early' implies an excuse for defective work of which I would not be supposed blind to the defects—such as the 'Gipsy Child,' which you suggest for exclusion; but something these early pieces have which later work has not, and many people—perhaps for what are truth faults in the poems—have liked them. You have been a good friend to my poems from the first, one of those whose approbation has been a real source of pleasure to me. There are things which I should like to do in poetry before I die, and of which lines and bits have long been done, in particular Lucretius, St. Alexius, and the journey of Achilles after death to the Island of Leuce; but we accomplish what we can, not what we will."

Enough, perhaps, has now been said about his critical method; and, as this book proposes to deal with results, it is right to enquire into the effect of that method upon men who aspired to follow him, at whatever distance, in the path of criticism. The answer can be easily given. He taught us, first and foremost, to judge for ourPg 45selves; to take nothing at second hand; to bow the knee to no reputation, however high its pedestal in the Temple of Fame, unless we were satisfied of its right to stand where it was. Then he taught us to discriminate, even in what we loved best, between its excellences and its defects; to swallow nothing whole, but to chew the cud of disinterested meditation, and accept or reject, praise or blame, in accordance with our natural and deliberate taste. He taught us to love Beauty supremely, to ensue it, to be on the look out for it; and, when we found it—when we found what really and without convention satisfied our "sense for beauty"—to adore it, and, as far as we could, to imitate it. Contrariwise, he taught us to shun and eschew what was hideous, to make war upon it, and to be on our guard against its contaminating influence. And this teaching he applied alike to hideousness in character, sight, and sound—to "watchful jealousy" and rancour and uncleanness; to the "dismal Mapperly Hills," and the "uncomeliness of Margate," the "squalid streets of Bethnal Green," and "Coles' Truss Manufactory standing where it ought not, on the finest site in Europe"; to such poetry as—

to such hymns as—

"What a touch of grossness!" he exclaimed, "what an original shortcoming in the more delicate spiritual perceptions, is shown by the natural growth amongst us of such hideous names—Higginbottom, Stiggins, Bugg! In Ionia and Attica they were luckier in this respect than "the best race in the world"; by the Ilissus there was "no Wragg,[8] poor thing!"

Then he taught us to aim at sincerity in our intercourse with Nature. Never to describe her as others saw her, never to pretend a knowledge of her which we did not possess, never to endow her with fanciful attributes of our own or other people's imagining, never to assume her sympathy with mortal lots, never to forget that she, like humanity, has her dark, her awful, her revengeful moods. He taught us not to be ashamed of our own sense of fun, our own faculty of laughter; but to let them play freely even round the objects ofPg 47 our reasoned reverence, just in the spirit of the teacher who said that no man really believed in his religion till he could venture to joke about it. Above all, he taught us, even when our feelings were most forcibly aroused, to be serene, courteous, and humane; never to scold, or storm, or bully; and to avoid like a pestilence such brutality as that of the Saturday Review when it said that something or another was "eminently worthy of a great nation," and to disparage it "eminently worthy of a great fool." He laid it down as a "precious truth" that one's effectiveness depends upon "the power of persuasion, of charm; that without this all fury, energy, reasoning power, acquirement, are thrown away and only render their owner more miserable."

In a word, he combined Light with Sweetness, and in the combination lies his abiding power.

"Though I am a schoolmaster's son, I confess that school-teaching or school-inspecting is not the line of life I should naturally have chosen. I adopted it in order to marry a lady who is here to-night, and who feels your kindness as warmly and gratefully as I do. My wife and I had a wandering life of it at first. There were but three lay-inspectors for all England. My district went right across from Pembroke Dock to Great Yarmouth. We had no home. One of our children was born in a lodging at Derby, with a workhouse, if I recollect aright, behind and a penitentiary in front. But the irksomeness of my new duties was what I felt most, and during the first year or so it was sometimes insupportable."

The name of Arnold is so inseparably connected with Education[9] that many of Matthew Arnold'sPg 49 friends were astonished by this frank confession, which he made in his address to the Westminster Teachers' Association on the occasion of his retirement from the office of Inspector. There is reason to believe that the profession on which he had set his early affections was Diplomacy. It is easy to see how perfectly, in many respects, diplomatic life would have suited him. The proceeds of his Fellowship, then considerable and unhampered by any conditions of residence, would have supplied the lack of private fortune. He had some of the diplomatist's most necessary gifts—love of travel, familiarity with European literature, keen interest in foreign politics and institutions, taste for cultivated society, rich enjoyment of life, and fascinating manners conspicuously free from English stiffness and shyness. As to his interest in foreign politics, it is only necessary to cite England and the Italian Question, which he wrote in 1859, and which deals with the unity and independence of Italy. It is the first essay which he ever published, but it abounds in clearness and force, and is entirely free from the whimsicality which in later years sometimes marred his prose. Above all it shows a sympathetic insight into foreign aspirations which is rare indeed even among cultivated Englishmen. In reference to this pamphlet he truly observed: "The worst of the English is that onPg 50 foreign politics they search so very much more for what they like and wish to be true, than for what is true. In Paris there is certainly a larger body of people than in London who treat foreign politics as a science, as a matter to know upon before feeling upon."

As regards the diplomatic life, it seems certain that he would have enjoyed it thoroughly, and one would think that he was exactly the man to conduct a delicate negotiation with tact, good humour, and good sense. Some glimmering of these gifts seems to have dawned from time to time on the unimaginative minds of his official chiefs; for three times he was sent by the Education Office on Foreign Missions, half diplomatic in their character, to enquire into the condition and methods of Public Instruction on the Continent. The ever-increasing popularity which attended him on these Missions, and his excellent judgment in handling Foreign Ministers and officials, might perhaps suggest the thought that in renouncing diplomacy he renounced his true vocation. But the thought, though natural, is superficial, and must give way to the absolute conviction that he never could have known true happiness—never realized his own ideal of life—without a wife, a family, and a home. And these are luxuries which, as a rule, diplomatists cannot attain till

have lost something of their freshness. In renouncing diplomacy he secured, before he was twenty-nine, the chief boon of human life; but a vague desire to enjoy that boon amid continental surroundings seems constantly to have visited him. In 1851 he wrote to his wife: "We can always look forward to retiring to Italy on £200 a year." In 1853 he wrote to her again: "All this afternoon I have been haunted by a vision of living with you at Berne, on a diplomatic appointment, and how different that would be from this incessant grind in schools." And, thirty years later, when he was approaching the end of his official life, he wrote a friend: "I must go once more to America to see my daughter, who is going to be married to an American, settled in her new home. Then I 'feel like' retiring to Florence, and rarely moving from it again."

But, in spite of all these dreams and longings, he seems to have known that his lot was cast in England, and that England must be the sphere of his main activities. "Year slips away after year, and one begins to find that the Office has really had the main part of one's life, and that little remains."

We, who are his disciples, habitually think of him as a poet, or a critic, or an instructor in national righteousness and intelligence; as a modelPg 52 of private virtue and of public spirit. We do not habitually think of him as, in the narrow and technical sense, an Educator. And yet a man who gives his life to a profession must be in a great measure judged by what he accomplished in and through that profession, even though in the first instance he "adopted it in order to marry."

Though not a born educator, not an educator by natural aptitude or inclination, he made himself an educator by choice; and, having once chosen his profession, he gradually developed an interest in it, a pride in it, a love of it which astonished some of his friends. How irksome it was to him at the beginning we saw just now in his address to the Teachers. How irksome in many of its incidents it remained we can see in his published Letters.

"I have had a hard day. Thirty pupil-teachers to examine in an inconvenient room, and nothing to eat except a biscuit which a charitable lady gave me."

"This certainly has been one of the most uncomfortable weeks I ever spent. Battersea is so far off, the roads so execrable, and the rain so incessant.... There is not a yard of flagging, I believe, in all Battersea."

"Here is my programme for this afternoon: Avalanches—The Steam-Engine—The Thames—Pg 53India-Rubber—Bricks—The Battle of Poictiers—Subtraction—The Reindeer—The Gunpowder Plot—The Jordan. Alluring, is it not? Twenty minutes each, and the days of one's life are only three score years and ten."

"About four o'clock I found myself so exhausted, having eaten nothing since breakfast, that I sent out for a bun, and ate it before the astonished school."

"Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday I had to be at the Westminster Training School at ten o'clock; be there till half-past one, and begin again at two, going on till half-past six; this, with eighty candidates to look after, and gas burning most of the day, either to give light or to help to warm the room."

"One sees a teacher holding up an apple to a gallery of little children, and saying: 'An apple has a stalk, peel, pulp, core, pips, and juice; it is odorous and opaque, and is used for making a pleasant drink called cider.'"

"I sometimes grow impatient of getting old amid a press of occupation and labour for which, after all, I was not born.... The work I like is not very compatible with any other. But we are not here to have facilities found us for doing the work we like, but to make them."

Still, his work as an inspector might have beenPg 54 made more interesting and less irksome, if he had served under chiefs of more enlightened or more liberal temper, as may be inferred from some words uttered after his retirement—

"To Government I owe nothing. But then I have always remembered that, under our Parliamentary system, the Government probably takes little interest in such work, whatever it is, as I have been able to do in the public service, and even perhaps knows nothing at all about it. But we must take the evil of our system along with the good. Abroad probably a Minister might have known more about my performances; but then abroad I doubt whether I should ever have survived to perform them. Under the strict bureaucratic system abroad, I feel pretty sure that I should have been dismissed ten times over for the freedom with which on various occasions I have exposed myself on matters of Religion and Politics. Our Government here in England takes a large and liberal view about what it considers a man's private affairs, and so I have been able to survive as an Inspector for thirty-five years; and to the Government I at least owe this—to have been allowed to survive."

For thirty-five years then he served his country as an Inspector of Elementary Schools, and the experience which he thus gained, the interest whichPg 55 was thus awoke in him, suggested to him some large and far-reaching views about our entire system of National Education. It is no disparagement to a highly-cultivated and laborious staff of public servants to say that he was the greatest Inspector of Schools that we have ever possessed. It is true that he was not, as the manner of some is, omnidoct and omnidocent. His incapacity to examine little girls in needlework he frankly confessed; and his incapacity to examine them in music, if unconfessed, was not less real. "I assure you," he said to the Westminster Teachers, "I am not at all a harsh judge of myself; but I know perfectly well that there have been much better inspectors than I." Once, when a flood of compliments threatened to overwhelm him, he waved it off with the frank admission—"Nobody can say I am a punctual Inspector." Why then do we call him the greatest Inspector that we ever had? Because he had that most precious of all combinations—a genius and a heart. Trying to account for what he could not ignore—his immense popularity with the masters and mistresses of the schools which he inspected—he attributed part of it to the fact that he was Dr. Arnold's son, part to the fact that he was "more or less known to the public as an author"; but, of personal qualifications for his office, he enumerated two only,Pg 56 and both eminently characteristic: "One is that, having a serious sense of the nature and function of criticism, I from the first sought to see the schools as they really were; thus it was felt that I was fair, and that the teachers had not to apprehend from me crotchets, pedantries, humours, favouritism, and prejudices." The other was that he had learnt to sympathize with the teachers. "I met daily in the schools men and women discharging duties akin to mine, duties as irksome as mine, duties less well paid than mine; and I asked myself: Are they on roses? Gradually it grew into a habit with me to put myself into their places, to try and enter into their feelings, to represent to myself their life."

It belongs to the very nature of an Inspector's work that it escapes public notice. Very few are the people who care to inform themselves about the studies, the discipline, the intellectual and moral atmosphere of Elementary Schools, except in so far as those schools can be made battle-grounds for sectarian animosity. And, if they are few now, they were still fewer during the thirty-five years of Arnold's Inspectorship. A conspicuous service was rendered both to the cause of Education and to Arnold's memory when the late Lord Sandford rescued from the entombing blue-books his friend's nineteen General Reports to the EduPg 57cation Department on Elementary Schools. In those Reports we read his deliberate judgment on the merits, defects, needs, possibilities and ideals of elementary schools; and this not merely as regards the choice of subjects taught, but as regards cleanliness, healthiness, good order, good manners, relations between teachers and pupils, selection of models in prose and verse, and the literary as contrasted with the polemical use of the Bible.

Such an enumeration may sound dull enough, but there is no dulness in the Reports themselves. They are stamped from the first page to the last with his lightness of touch and perfection of style. They belong as essentially to literature as his Essays or his Lectures.

In reading these Reports on Elementary Schools we catch repeated allusions to his three Missions of enquiry into Education on the Continent. Those Missions produced separate Reports of their own, and each Report developed into a volume. "The Popular Education of France" gave the experience which he acquired in 1859, and its Introduction is reproduced in Mixed Essays under the title of "Democracy." A French Eton (not very happily named) was an unofficial product of the same tour; for, extending his purview from Elementary Education, he there dealt with the relation between "Middle Class Education and the State."

"Why," he asked, "cannot we have throughout England as the French have throughout France, as the Germans have throughout Germany, as the Swiss have throughout Switzerland, and as the Dutch have throughout Holland, schools where the middle and professional classes may obtain at the rate of from £20 to £50 a year if they are boarders, and from £5 to £15 a year if they are day scholars, an education of as good quality, with as good guarantees of social character and advantages for a future career in the world, as the education which French children of the corresponding class can obtain from institutions like that of Toulouse or Sorèze?"

Schools and Universities of the Continent gave the result of the Mission in 1865 to investigate the Education of the Upper and Middle Classes in France, Italy, Germany, and Switzerland. Its bearing on English Education may be inferred from these words of its author, written in October, 1868: "There is a vicious article in the new Quarterly on my school-book, by one of the Eton undermasters, who, like Demetrius the Silversmith, seems alarmed for the gains of his occupation."

The "Special Report on Elementary Education Abroad" grew out of his third Mission in 1885; and, over and above these books, dealing specifically with educational problems, we meet constantPg 59 allusions to the same topics in nearly all his prose-writings. A life-long contact with Education produced in him a profound dissatisfaction with our English system, or want of system, and an almost passionate desire to turn chaos into order by the persistent use of the critical method.

When one talks about English Education, the subject naturally divides itself into the Universities, the Public Schools, the Private Schools, and the Elementary Schools. The classification is not scientifically accurate, but it will serve. With all these strata of Education, he in turn concerned himself; but with the two higher strata much less effectively than with the two lower. It was necessary to the theoretical completeness of his scheme for organizing National Education, that the Universities and the Public Schools, as well as the Private and the Elementary Schools, should be criticised; but, in dealing with the former, his criticism is far less drastic and insistent than with the latter. The reason of the difference probably is that, though an Inspector, a Professor, and a critic, he was frankly human, and shrank from laying his hand too roughly on institutions to which he himself had owed so much.

His feeling for Oxford every one knows. The apostrophe to the "Adorable Dreamer" is familiar to hundreds who could not, for their life, repeatPg 60 another line of his prose or verse. It was "the place he liked best in the world." When he climbed the hill at Hinksey and looked down on Oxford, he "could not describe the effect which this landscape always has upon me—the hillside, with its valleys, and Oxford in the great Thames Valley below."

Of the spiritual effect of the place upon hearts nurtured there, he said: "We in Oxford, brought up amidst the beauty and sweetness of that beautiful place, have not failed to seize one truth—the truth that beauty and sweetness are essential characters of a complete human perfection. When I insist on this, I am all in the faith and tradition of Oxford."

Of the Honorary Degree conferred on him by Oxford, he said: "Nothing could more gratify me, I think, than this recognition by my own University, of which I am so fond, and where, according to their own established standard of distinction, I did so little." And, after the Encænia at which the degree was actually given, he wrote: "I felt sure I should be well received, because there is so much of an Oxford character about what I have written, and the undergraduates are the last people to bear one a grudge for having occasionally chaffed them."

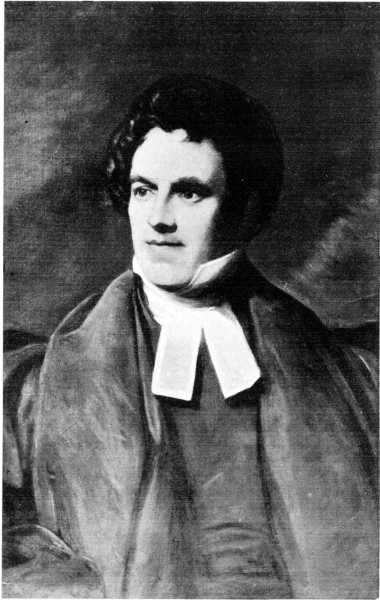

And here let me insert the moving passage inPg 61 which, speaking in his last years to an American audience, he did honour to the spiritual master of his undergraduate days. "Forty years ago Cardinal Newman was in the very prime of life; he was close at hand to us at Oxford; he was preaching in St. Mary's pulpit every Sunday; he seemed about to transform and to renew what was for us the most national and natural institution in the world, the Church of England. Who could resist the charm of that spiritual apparition, gliding in the dim afternoon light through the aisles of St. Mary's, rising into the pulpit, and then, in the most entrancing of voices, breaking the silence with words and thoughts which were a religious music—subtle, sweet, mournful? I seem to hear him still.... Or, if we followed him back to his seclusion at Littlemore, that dreary village by the London road, and to the house of retreat and the church which he built there—a mean house such as Paul might have lived in when he was tent-making at Ephesus, a church plain and thinly sown with worshippers—who could resist him there either, welcoming back to the severe joys of Church-fellowship, and of daily worship and prayer, the firstlings of a generation which had well-nigh forgotten them?"

When we bear in mind this devotion to Oxford, it is not surprising that he dealt very gently withPg 62 the defects of English Universities. In 1868 he laid it down that the University ought to provide facilities, after the general education is finished, for the cultivation of special aptitudes. "Our great Universities," he said, "Oxford and Cambridge, do next to nothing towards this end. They are, as Signor Mateucci called them, hauts lycées; and, though invaluable in their way as places where the youth of the upper class prolong to a very great age, and under some very valuable influences, their school-education, yet, with their college and tutor system, nay, with their examination and degree system, they are still, in fact, schools, and do not carry education beyond the stage of general and school education." This is just in the spirit of his famous quotation about the Oxford which he loved so well—

In 1875 he wrote: "I do not at all like the course for the History School (at Oxford). Nothing but read, read, read, endless histories in English, many of them by quite second-rate men; nothing to form the mind as reading truly great authors forms it, or even to exercise it, as learning a new language, or mathematics, or one of the natural sciences exercises it.... The regulation of studies is all-important, and there is no one to regPg 63ulate them, and people think that anyone can regulate them. We shall never do any good till we get a man like Guizot, or W. von Humboldt to deal with the matter, men who have the highest mental training themselves, and this we shall probably in this country never get."

In the wittiest of all his books, and one of the wisest, Friendship's Garland,[10] he thus summarized the too-usual result of our "grand, old, fortifying, classical curriculum." To his Prussian friend enquiring what benefit Lord Lumpington and the Rev. Esau Hittall have derived from that curriculum, that "course of mental gymnastics," the imaginary Arnold replied: "Well, during their three years at Oxford, they were so much occupied with Bullingdon and hunting that there was no great opportunity to judge. But for my own part, I have always thought that their both getting their degrees at last with flying colours, after three weeks of a famous coach for fast men, four nights without going to bed, and an incredible consumption of wet towels, strong cigars, and brandy-and-water, was one of the most astonishing feats of mental gymnastics I ever heard of!"

It must be admitted that his effect on the Universities was not very tangible, not very positive. It was not the kind of effect which can be expressedPg 64 in figures or reported in Blue Books. One cannot stand in the High Street of Oxford, or on King's Parade at Cambridge, and point to an Institute, or a college, or a school of learning, and say: "Matthew Arnold made that what it is."

His effect was of a different kind. It was written on the fleshly tables of the heart. To Oxford men he seemed like an elder brother, brilliant, playful, lovable, yet profoundly wise; teaching us what to think, to admire, to avoid. His influence fell upon a thirsty and receptive soil. We drank it with delight; and it co-operated with all the best traditions of the place in making us lifelong lovers of romance, and truth, and beauty. One of the keenest minds produced by Oxford between 1870 and 1880 thus summarized his effect on us: "I think he was almost the only man who did not disappoint one."