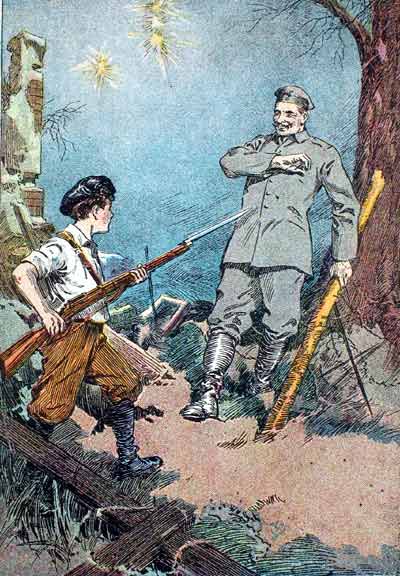

"I OUGHT TO DUMP YOU OUT."

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Children of France, by Ruth Royce

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Children of France

A Book of Stories of the Heroism and Self-sacrifice of

Youthful Patriots of France During the Great War

Author: Ruth Royce

Release Date: August 4, 2005 [EBook #16437]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE CHILDREN OF FRANCE ***

Produced by Michelle Croyle, Sankar Viswanathan and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

"I OUGHT TO DUMP YOU OUT."

Transcriber's Note:

Pagination for blank pages is omitted in the margin numbering.

While the Author cannot personally vouch for the stories related in this volume, she has full confidence in the sources of her information—men who have seen and heard on the battlefields of France, and who have related to her these and many other like incidents illustrating the heroism of the Children of France. Some of the stories the relators have learned through personal observation, while others have come to them indirectly. The author, therefore, believes each story set down here to be authentic, and so offers them to the liberty-loving boys and girls of America.

THE AUTHOR

The story of the heroism of the Children of France never will be fully told. Many of these little patriots have suffered the supreme penalty for their devotion to their country, leaving neither track nor trace of themselves. That they have disappeared is all that is known of them, and thus the stories of their deeds of valor have died with them.

In no other period of the world's history have there been so many instances of self-sacrificing patriotism on the part of children as have come from France during the great war. Through all such stories as have come to light, there runs a spirit of heroism that is sublime. Such stories should and will prove an inspiration to every boy and girl of America and surely will lead them up to a more perfect manhood and womanhood.

In this little volume are set down the stories of many devoted little French boys and girls, some of whom have offered their lives for their country, others of whom have passed through perils that would try the strongest and bravest of men, and yet lived to be honored by a grateful government for their deeds of heroism. How Remi the Brave, a lad of ten, won the Cross of War; the story of Little Mathilde who saved the French garrison from the Uhlan raiders; Marie the Courageous, who remained at home when the Germans captured the town in which she lived, and kept the French informed, knowing that if caught she would surely be shot as a spy; how the Hero of the Guns saved the day by working the machine guns when nearly all their crews were dead or wounded; the story of the Little Soldier of Mercy who, though a timid lad, forgot his fears, and working under fire saved the life of many a wounded man; how Little Gené locked the Bavarian Dragoons in the cellar of her home and captured the [7] lot of them, are a few of the thrilling tales of the patriotism and heroism of the Children of France that form one of the most fascinating chapters in the history of the great world war. They will make the heart of every boy and girl beat faster, they will grip the heartstrings of all who read and bring them to a better realization of their duty to their Flag and to their Country.

Before the "Squire's" son went away to war, the neighborhood children knew him only by sight and by hearing their parents speak of him as the son of "the richest man in Titusville," who never had done a day's work in his life.

Perhaps the parents were not quite right in this, for, even if Robert Favor had not gone out in the fields to labor, he had graduated from high school and college with high honors. He never spoke to the village children nor noticed them, and was not, as a result, very popular with the young people of his home town. The neighbors [10] said this was all on account of his bringing up.

It was therefore a surprise to them when, at the beginning of the great war, after Germany swept over Belgium, Robert Favor hurried to Europe. It was later learned that he had joined what is known as the "Foreign Legion" of the French Army. Titusville next heard that he had been made a lieutenant for heroic conduct under fire. But Titusville did not believe it; it said no Favor ever did anything but run away in such circumstances. But they believed it when, later on, they read in the newspapers how Lieutenant Favor had sprung out of the trenches and ran to the rescue of a wounded private soldier who had lain in a shell hole in No Man's Land since the night before.

The village swelled with pride and the eyes of the children grew wide with wonder as they listened to the story of the heroism of the Squire's son. But this was as nothing to what occurred later. "Bob" Favor was [11] brought home one day to the house on the hill, pale and weak from wounds received in battle.

Spring was at hand, and as soon as he was able, Captain Favor—you see he had again been promoted—was taken out on the lawn where, in his wheel chair he rested in the warm sunshine. The bright red top of his gray-blue cap, and the flash of the medal on his breast excited the wonder of the children, who pressed their faces against the high iron fence and gazed in awe. It was the first real hero any of them ever had seen.

Finally, chancing to look their way, the Captain smiled and waved a friendly hand. A little girl clapped her hands, others started to cheer and a little man of ten dragged an American flag from his pocket and waved it. The Captain beckoned to the children.

"Come in, folks," he called. "I wish some one to talk to me and make me laugh. Are you coming?"

They were. The children started, at first hesitatingly, then with more confidence, led by the boy with the American flag, which he was waving bravely now.

"What's your name?" demanded the Captain.

"Joe Funk, sir."

The Captain laughed. "No boy so patriotic as you are should have a name like that," he said. "We all are going to be great friends, I am sure, and when I get this leg, that a German shell nearly blew off, in working order again, we shall have some real sport and I'll teach you all how to be soldiers. Just now I cannot do much of anything."

"Yes, you can," interrupted Joe. "You can tell us how you rescued the soldier when the Germans were shooting at you and—"

"Master Joseph," answered the Captain gravely, "a real soldier never brags about himself; but what you say does give me an idea. How would you like to have me tell [13] you about the brave little children of France?"

"Well, I'd rather hear about how you killed the Germans, lots of 'em; I want to hear about battles and dead men and—"

"We shall speak of the children first, and I will begin right now. Let me see. Ah! I have it. Sit down on the grass, all of you, and be comfortable. Be quiet until I finish the story, then ask what questions you wish. Now listen!"

"He was a little French peasant lad, this boy Remi that I shall tell you about, and had just passed his tenth birthday when the Germans invaded his beloved country," began the Captain.

"Remi continued on at school in spite of the excitement about him, for everyone was talking about the war, but his heart was with the soldiers whom he knew were marching forth in thousands to meet the enemy. One day his father was called to the colors and the child was left in the care of an uncle.

"Now, this uncle belonged to a military organization called the Territorials, something like our National Guard, and a few weeks later they also were called to march [16] forth and join the French Army. Remi was to be left in the care of the neighbors. That was the plan made by the uncle. The little French lad, however, had his own ideas about that, but kept his plans to himself. He now forgot all about going to school, and spent his time watching his uncle's comrades drill—watched until he knew every command, every evolution so well that he himself could have drilled the company of his uncle.

"As you children perhaps already have surmised, it was Remi's plan to go to war and fight for his country. The order for the Territorials to move came suddenly, as such orders most always do. They came while the lad was having a supper of black bread and cheese with a friendly housewife of the neighborhood. The Territorials were to march within an hour.

"Remi's eyes grew bright. He stowed what was left of his meager supper into his blouse and strolled out. Once clear of the house, he ran swiftly to the edge of the [17] village, and from the end of a hollow log drew forth a canvas bag. He inspected the contents, which included a knife, some string, a clean pair of stockings and one change of underwear. He had picked up an old pack discarded by a soldier, and made it his own, secreting it for just such a moment as this. The child stowed his belongings back in the pack, added the cheese and bread, and, swinging the pack over his shoulder, started at a brisk trot for the gathering place of the Territorials. The men of his uncle's company already had reached the scene, loaded down with equipment, rifles brightly polished, looking very warlike with their outfits and tin derbies—"

"What's a tin derby?" interjected Joe Funk.

"There, you have interrupted me," rebuked the Captain. "Remember, a soldier's first duty is to obey orders. A tin derby is a steel helmet or hat which is used as a protection against the splinters thrown off [18] from an exploding shell. Where was I?"

"In a tin derby, sir," reminded Joe Funk.

"Little Remi," continued the Captain, "kept in the background and, in the excitement of the moment attracted no attention. Shortly after his arrival the Territorials fell into line and started away. Remi melted away in the darkness, and might have been observed legging it across a field in a short cut to a point where he knew the soldiers would pass. And, after they had marched by he fell in at a safe distance behind and trudged along on his way to war.

"Daylight came; the men halted for breakfast, and the boy, secreting himself by the roadside, munched his bread and cheese and waited for the soldiers to resume the march. All day long he followed them as closely as he dared, but early in the second evening he made bold to draw up to the rear rank and plodded along behind it until they halted for rest. Suddenly the lad felt a firm [19] hand on his shoulder. He found his uncle frowning down upon him.

"'What are you doing here?' demanded the uncle severely. 'Home with you as fast as you can go!'

"'But, uncle, I wish to be a soldier. I am little but I am strong. See, I have marched a day and a night and you, my uncle, are weary, while Remi is still fresh as the morning flowers.'

"'Yes, but what can you do in the Army, my Remi?'

"'I can fight,' answered the child simply, whereat the uncle shrugged his shoulders in token of surrender.

"At first the officers were for sending the lad home, but he was making himself so useful in many little ways, and his patriotism was so deep and true that he finally was permitted to remain.

"What most disturbed Remi was that he had no rifle. The soldiers laughed at him when he demanded one, so he determined to get one for himself at the first opportunity.

"By this time they were well within sound of the big guns. The sound reminded him of a distant thunderstorm. It grew louder as the hours passed and the men neared the front. All understood what the sound meant. To Remi that distant roar was the sweetest music he ever had heard.

"The Territorials finally were halted in a shell-torn village for a brief rest. Men were urgently needed at the front, and Remi's companions soon entered a communicating trench that began under a house in the village, and started for the firing line, a short distance from the German trenches. Remi was sternly ordered to remain behind. This order nearly broke his heart and, when he more fully realized that he had been left behind, he sat down and gave way to, bitter tears.

"A peculiar whistling sound in the air suddenly attracted his attention. The strange sound grew louder. He stood up. Then, with a mighty crash and roar, the earth about him rose up and darkness overwhelmed [21] him. A German shell had landed fairly in the village street hard by and half buried the child in the wreckage. Remi, bruised and with clothing torn, dug himself out practically unharmed. He shook his fist in the direction of the German lines.

"'The Boches!' he breathed, clenching both fists. 'I must have a rifle. Having none, I am good for nothing.'

"For a few moments he stood observing the stretcher men gathering up those who had been wounded in the explosion. He did not quail at sight of the maimed forms before him—he was unafraid, but his childish face drew down into hard lines that made him look years older. He knew now that he must join his company and fight for France. After what he had seen nothing should hold him back. Perhaps once at the front he might find a gun. Remi tried to enter the communicating trench, but was stopped by a sentry. He was still undaunted. It was the odor of cooking that finally led to the solution of his problem. He followed [22] his nose, as the saying goes, because he was hungry. He found the cooks at work, as he learned, preparing food to be carried to the men in the front-line trench. The boy promptly offered his services to help carry in the food. You see, Remi used his head.

"'What nursery do you belong to?' jeered the mess sergeant.

"'Thirty-first Territorials, Company C,' answered the lad promptly, his quick reply bringing a laugh in which the mess sergeant joined heartily.

"'All right, take a load of coffee and follow the leader, but if you spill so much as a drop of it you'll face a firing squad at daybreak.'

"Two heavy containers filled with hot coffee, suspended from a yoke that fitted over the shoulders, were placed on the lad. The soldiers expected to see him collapse under the heavy load, but Remi stood up very straight and awaited the command to go forward. He was stronger than they [23] thought he was. The journey through the dark trenches was a long one, made thrilling by the Germans, who were trying to drop shells into them as the food was coming up to the front line. The 'chow' carriers, however, arrived safely at Company C's station and Remi had every drop of coffee that he had started out with.

"'Well, here I am,' he announced loudly. 'Remi wants a gun, he wants it right away, and then he wants to see a Boche.'

"'You'll see him sooner than you expect if you don't lower your voice,' rebuked a soldier.

"At that moment a star-shell shot high up into the air and, bursting, flooded the space between the French and German lines with a brilliant light. Remi peered over the top of the parapet and across the 'No Man's Land' of which he had so often heard, over its barbed-wire entanglements and on to the parapets of the German trenches.

"'Why do they do that?' he questioned. [24]

"'To see if any of our patrols are out there nosing about. You see, we send out night patrols to find out what the enemy is doing,' he was told.

"'I, too, shall be a night patrol,' declared the lad confidently.

"Unmindful of the desperate chance he was taking, Remi, watching his opportunity, slipped over the top of the French trench and began crawling toward the enemy lines. He did not know where the openings in the wire entanglements were located, but, being small, he was able to crawl under. Now and then he saw other figures slinking about out there, but he took good care that they should not see him, and, when another star shell was fired, he flattened himself on the ground, face downward, and thus avoided detection. So intent was he, however, in watching for enemy patrols that he actually bumped into the parapet of the German trench before he knew it. The boy flattened himself on the ground and listened. He heard low-toned conversation [25] mingled with German snores in the trench, and sniffed contemptuously. Raising a hand to pull himself up to the top of the sandbags, he struck something sharp. It was the point of a bayonet. Remi's hand crept cautiously along and the lad barely escaped an exclamation, for here, right in his hand, was a German rifle aimed toward his own lines, ready to be fired at his beloved French comrades.

"Cautiously drawing the weapon over the parapet, he caressed it affectionately, then started to crawl back toward his own lines with his precious find.

"'At last Remi has a rifle, and none shall take it from him,' he muttered triumphantly. 'See what I have!' he cried after having been challenged and hauled into his own trench. 'I took it from the thickheads over there. I—' He said no more, for his comrades were hugging him delightedly. They hurried the child off to the captain of his company, who, after listening to the story, embraced Remi. [26]

"'Ah, you are a true Frenchman,' cried the officer. 'Keep the gun and use it for our beloved France.'

"'I will,' promised Remi solemnly.

"Two nights later he stole out and fetched back five more German rifles. By this time the officers began to realize that the boy must be taken seriously. From that night on almost every night found the intrepid lad skulking about over 'No Man's Land,' many times with the enemy's machine gun fire snapping about his ears, but to which he gave not the slightest heed. Remi truly seemed to bear a charmed life.

"One night after his company had returned to the front-line trench, after a night's rest in 'billets,' he went out with the patrol, as usual, but with a new plan in mind. By now he knew the arrangement of the German trenches almost as well as did the men who occupied them. There were ten in the patrol, and so great was the confidence of the men in him that they virtually permitted Remi to act as their [27] leader. The patrol carried no rifles, only revolvers and stout clubs, like policemen's night sticks. When the lad ordered the men to secret themselves in a shell crater, they obeyed willingly.

"Remi reached the German trenches, along which he crept with ears and eyes on the alert.

"'Who goes!' came a sharp, low-spoken command in German. At that instant a German rose from the ground, where he had been crouching, apparently watching the crawling figure of the little Frenchman. Remi rose at the same time, a Boche bayonet pressing against his stomach.

"When the German sentinel discovered that the 'man' confronting him was only a child, he threw back his head and laughed silently, his bulky form shaking with merriment. That laugh cost the Boche his liberty. Like a flash little Remi swept the bayonet aside and jerked the rifle from the sentry's hands. He sprang back and pointed the rifle at his amazed adversary.

"'Now march!' he commanded in a low, sharp tone. Straight to the shell crater the little Frenchman drove his prisoner, thence sent the captive to the French trenches with an escort. He then returned to the German trench. As he thought it over the situation became clear to him. The Germans had placed the sentry outside the trench to keep watch while they slept, the night being a quiet one, neither side having fired a shot since sundown. Knowing exactly what he wished to do, the boy began cautiously removing the rifles from the parapet, placing them on the ground in front of the trench. He accomplished his purpose without disturbing the snores of the Boches.

"Having secured the enemy's rifles, Remi crept back to the shell hole, where his comrades were anxiously awaiting his return.

"'Come,' he urged. 'We shall now capture the stupid fellows. They sleep, the thickheads. Their rifles I have taken, their heads our clubs shall find. All shall have [29] the big headache when we have finished with them.'

"The men of the patrol were amazed. They scrambled from the shell hole, Remi already having explained what he proposed to do, ready and eager for action. With the child in the lead they crept up to the German trench. The Boches slept on, not a man was awake there. The patrol spread out a little and gripped their clubs, for to use revolvers would be to arouse the whole German line and start their rifles, machine guns and artillery all going.

"'Now!' cried the little leader.

"The patrol sprang into the trench, Remi leading, encouraging his men as they fought their way along with their stout clubs, the boy having lost his when he slipped into the trench. He could plainly hear the whacks of the clubs as the patrol brought them down on the heads of the enemy, mingled with German growls and pleas for mercy, all of which brought joy to the soul of little Remi.

"'Kamerad! Kamerad!' came cries along the length of the trench. This, you children understand, is what the Boches say when they have had enough.

"'Stop their noise! They'll have their whole army down on us. Over the top and home with them as fast as you can. Gather up the rifles and take them in,' commanded the boy.

"Prodded by the handy clubs, such of the Germans as had survived the terrible beating willingly clambered over the top and were quietly driven across 'No Man's Land' to the French trenches. Seventy-five prisoners were taken in that raid, planned and executed by the fearless little French boy.

"The amazement of his comrades in Company C was beyond the power of words to express. What was better still, the raid was productive of much more than prisoners and rifles. It proved to be the most important raid so far made on that sector, for information was obtained from the prisoners that proved of great value to the French army.

"NOW MARCH!" HE COMMANDED.

"A few days later the Territorials went back to their billets for rest. On the morning following their arrival there, Company C was called out with many other troops for review. Remi thought this was a queer thing to do. He was puzzled and startled when his name was called out as he stood in a rear rank. He was ordered to report to the colonel of the regiment, who stood with his aides facing the lines of soldiers, the latter at attention now. The heart of the little soldier, for once, was filled with fear. He felt certain that the colonel was going to send him home.

"Approaching the stern-looking officer, Remi halted, came stiffly to attention and saluted with precision. The colonel gravely answered the little fellow's salute. Remi looked very small and childish beside the commanding figure of his colonel, and he was very much embarrassed at being so singled out.

[32] "'Remi, soldier of France, the Army and your country salute you,' began the colonel. 'The hearts of both are filled with pride at your brave deeds. You are an honor to the tri-color of our beloved France, under the folds of which you now are standing. Were it possible for me to do so I should make you no less than a captain. Your lack of years puts such a reward beyond my power to give. I can, however, and I am authorized so to do, to confer upon you the cross of war, given only to men of proved heroism. Remi, I decorate you with this cross,' said the colonel, stepping forward and pinning the medal to the little soldier's breast, his aides standing at attention during the impressive ceremony. 'Wear it with honor, my son, for our beloved country.'

"The colonel then kissed the child on both cheeks.

"And Remi the bold, very pale and trembling, stammered his thanks, sat down heavily, and, burying his face in his hands, burst into tears."

"I've been thinking about that boy Remi," said Joe Funk next day when the children had gathered on the lawn to listen to another story. "Of course, I know he was a hero, but wasn't he something of a baby to sit down and cry like that?"

"Are you a baby, Joe?"

"'Course I'm not."

"Very good. You were wiping a tear out of the corner of one eye when I finished the story," returned Captain Favor dryly.

"I—I guess you are right, sir. Please tell us another one like it."

"Surely; but this one will be about a little French heroine named Mathilde. Mathilde was of nearly the same age as Remi, very diffident, like yourself." Joe blushed [34] and hung his head. "She was as timid as she was diffident, but at heart she was a heroic little French girl. They are all like Remi and Mathilde over there.

"This little woman lived in a French garrison town. Not more than two hundred soldiers were stationed there, all the others being at the front fighting the Germans. Quite near the village was an important fort, situated on the River Meuse. It was called Fort Montere and was very carefully guarded by these soldiers.

"The fort was situated about a mile from the village on a rise of ground. It was the custom of the soldiers there to spend a good part of their days in the village, never dreaming that they were in the slightest danger, but the Germans were nearer than they thought.

"One night—it was not far from morning, then—two companies of mounted Germans rode up to the sleeping village, which they surrounded. The commanding officer sent an aide to the mayor, ordering him to [35] see to it that not a person left his home on pain of instant death. The mayor refused to betray his people or the soldiers on the hill. The aide shot him then and there. That was nothing new for a German officer to do. Many worse acts than that have they committed. I know, for I have fought them, and I have seen many things. The people were then notified that disobedience meant further that the village would be burned.

"Not one of the villagers was bold enough to try to warn the French garrison of the peril that awaited them, for it was plain that the Germans were planning to lay in wait for the Frenchmen when they came to the village on the following morning.

"Soon German soldiers began entering the houses, one soldier to each house, in which he took his station, cowering the occupants by terrible threats.

"Little Mathilde, when she heard the soldier assigned to their home bang on the door with the butt of his rifle, fled to the kitchen, where she stood listening and [36] watching. She nearly cried out when the soldier thrust the bayonet of his rifle at her father, and all the resentment of her race at such injustice rose up within her.

"'I shall save them,' she breathed.

"Mathilde slipped out through the kitchen door into the walled garden, and, climbing the wall, peered over. She could see German horsemen and German infantrymen everywhere, the moonlight flashing on their helmets and rifles as they moved rapidly about. How she should be able to get over the wall without discovery she did not know. A heavy black cloud at this moment drifted across the sky, hiding the face of the moon for a few moments, and when the cloud had passed Mathilde was no longer on the garden wall. She lay prone on the ground in a field on the opposite side of the wall. Horsemen were all about her. Now and then a horse narrowly missed stepping on her, and those Uhlans must have wondered that night why their horses were so skittish.

"Every time she saw an opening the little heroine would dart ahead; each time a cloud passed between earth and moon she gained a little distance. Once a Uhlan's horse jumped clear over her and kicked viciously at her after it had landed on its feet. You see, the grass in the fields was high, there being no men to cut it. Had it not been for the grass, Mathilde never could have accomplished what she did.

"At last she was clear of them, and then how she did run; she fairly flew up the hill, stopping only when a French sentry halted her to demand what she wanted.

"'I would speak with your captain,' panted Mathilde.

"The sentry laughed.

"'Think you my captain sits awake all night that he may receive calls from the villagers?' he demanded.

"'But,' begged the girl, 'the Uhlans have come. They are even now in the houses that they may come out and shoot you down when you go to the village tomorrow.'

"'You are dreaming, my pretty miss. Go back to your sleep. It is a nightmare you are telling me. Return and dream no more.'

"Mathilde begged and pleaded, to the great amusement of the sentry. The child grew angry. She stamped and raged. Then she adopted a new plan. Throwing herself on the ground the little girl rolled and screamed and screamed.

"'Stop it! You'll wake the garrison,' he commanded.

"'That is what Mathilde is trying to do,' answered the girl, then screamed louder than ever, and the sentry turned out the corporal's guard. The corporal sent a messenger to the village to see if the child was right.

"'If you believe me not, look yonder in the valley,' exclaimed the girl, impatiently. 'What see you?'

"'Nothing. Wait! I see the moonlight glistening on something, I should say on a tin sign on a tree.'

"Mathilde laughed ironically. 'It is indeed [39] a sign, a bad sign, monsieur Corporal. What you see is the moonlight reflected on the helmet of a German Uhlan. Ha! Now believe you the little Mathilde?'

"'Call the captain,' commanded the corporal.

"The commanding officer came hurrying out. He questioned the child and ere he had finished the messenger came running back.

"'The Germans are in force in the village,' cried the messenger. 'They hide in the houses and their sentries guard the approaches to the village.

"'Summon the garrison to arms!' commanded the captain. 'You are a noble child, Mathilde.'

"While a small force was left to guard the fort the others of the garrison went down and surrounded the village. They surprised and captured the sentries without firing a shot. These prisoners were taken to the fort and locked up, after which the French in the village fired a volley into the [40] air. As they expected, the Prussians guarding the houses rushed out and began shooting, but coming from the lighted houses into the darkness of the early morning, their eyes were not keen and only one volley from the French was necessary to fill the Germans with fear. The Germans very soon laid down their arms and surrendered. While some of the invaders were wounded, no one was killed. The entire German force was captured and marched, humiliated, to the fort on the hill.

"Next day, when the villagers came to a realization of what Mathilde had done, a purse was made up, every one giving of his little savings. This purse was presented to the child by the captain, in the presence of all his officers and many of his soldiers.

"Mathilde's eyes were bright. She held the bag of money in her arms for a moment, then, kissing it, placed it in the hands of the captain.

"'And I, monsieur le Capitaine, give it to our beloved France. She needs it more [41] than does the Little Mathilde, and with it Mathilde sends her love to the brave poilus of her beautiful France.'"

"This morning I shall tell you what little Francois did to the Germans, as well as what the Germans did to Francois," began Captain Favor at a following sitting on the lawn. "Joe, you will be thrilled when you hear the story of the desperate chances this little French boy of twelve took for his country.

"He, like all of his youthful friends, was a noble fellow and a hero, quick-witted and very bright. You would soon learn, were you in France, how keen and clever these French children are. Their wits have been greatly sharpened since the war began. But to our story—.

"The Prussians had reached a point on the west bank of the River R——, a narrow [44] stream some distance back and to the left of the battle front. On the right side of the river, a few miles from it, was the little village in which Francois lived. A detachment of French infantry had arrived at the town, having come there on word that the Germans were threatening the village.

"'Where are the Prussians?' demanded the captain of the mayor. He was eager to get at them.

"'On the other side of the river. Other French detachments have driven them away twice, but each time the Boches return. We have not seen them here in several days now,' the mayor informed him.

"'I must know their exact location and the size of their force. I cannot send one of my own soldiers. Have you a man in the village who can pass the lines and obtain the information I seek?'

"'I fear there are none, sir,' replied the mayor.

"Francis, who had been an eager [45] listener to this conversation, stepped forward at this juncture.

"'I will go, monsieur le Capitaine,' he said.

"'Ah! You know where they are?'

"'No, sir, but I know the country for many miles.'

"'But the Germans will catch you, and if they do you will be shot. I cannot permit one so young as you are to sacrifice himself.'

"Francois smiled. 'I have a grandmother living in the other village and she is sick. Should a lad not be permitted to visit his grandmother who is ill?' he asked.

"The French captain saw the point and smiled. 'Go, then, if you will, but be careful. If you succeed you truly will be a hero, my lad.'

"'Francois will find the Boches,' was the boy's confident reply.

"Without waiting for the captain to change his mind the lad set out and was soon out of sight of the village. Reaching [46] the river, he crept along the bank until he found the bridge he was looking for. Over this he crawled on hands and knees, and, reaching the other side of the river, he dodged along until he came to the village where the Prussians were supposed to be. Francois halted at a farmhouse where he was known. The farmer's wife was feeding the pigs, and she did not see him until he said:

"'Where are the Boches?'

"'Francois! What do you here?' she exclaimed.

"'I come to see my grandmother. But I see none of the enemy.'

"'Unhappy child, there are thousands of them over yonder. Do not go on, I beg of you. You surely will be shot.'

"'I go to see my grandmother. Good day, madame.' Francois plodded on across the fields in the direction indicated by the farmer's wife. Suddenly he saw a troop of Prussian cavalry approaching him at a gallop.

[47] "'Halt!' commanded the captain of the troop when they drew up near the boy. 'What do you here?'

"'Walking, sir. I go to see my grandmother who is ill.'

"The Prussian laughed. 'Do you not know that the villagers have been ordered to remain at home and that he who disobeys this order will be shot?' questioned the commander, sternly.

"'Ah, sir, that is well for the grown men and women, but for children who go to see their sick grandmothers—'

"'The order is for all. About face! March! You will be shot for your disobedience.'

"'But I must see my grandmother,' insisted the lad. 'She is ill, I tell you.'

"Two soldiers swung him about and marched him to their camp. As he neared the camp he saw many cannon and machine guns, large numbers of cavalrymen and infantry. He estimated as best he could how many of them there were. He saw, too, [48] that the cannon were being placed so their muzzles pointed toward the river. Francois nodded wisely.

"'It is to shoot over to our side of the river,' he said to himself. 'One would not think they could shoot so far as our village. But they shall find our fine French cannon can shoot farther.'

"His reflections were broken in upon rudely when he was thrust into what proved to be the guardhouse. In reality he was thrown in by the two soldiers who had picked him up and sent him sprawling on the floor. 'What less could one expect from a Boche?' he muttered. For aught he knew, he soon would get worse. A sentry was posted at the door and Francois was informed that if he tried to escape he would be shot then and there.

"The guard house also was used to store equipment in. There were, as he observed, many rifles stacked in rows and heaps of knapsacks, helmets and blankets. The only light in the cell-like room into which he had [49] been thrust came in through a narrow window high up and far out of his reach, a window small like those in a prison cell.

"It was not a pleasant situation in which little Francois found himself, but what fears he had were for the people of his village and the French troops there. He already had used his eyes to good advantage, and now had a very clear idea of the size of the German force and its equipment. 'I shall make my escape and hasten back to tell our brave captain what I have seen,' he promised himself.

"Escape, however, was not so easy. The window was too high by several feet for him to reach and to go out through the door meant that he surely would be shot or bayoneted. His bright little eyes swept the room and instantly he saw a way of escape.

"'The bags!' he exclaimed, and straight-way began piling the knapsacks and blankets underneath the window. The pile grew slowly. At last it was high enough to permit the boy to reach the window sill with [50] his finger tips by standing on tip-toe on the pile he had built up.

"He drew himself up easily, for Francois was strong, and peered out.

"'It is well that Francois is little, for the window is small even for a dog to squeeze through,' he muttered.

"Peering out to see what lay before him, he saw a garden in the rear of the building and beyond that fields with hedges and bushes, but there was not a soldier in sight on that side. The Prussians were busy on the other side of the building preparing for action.

"'All is well,' said Francois. A new idea came to him. He would take a German rifle and helmet with him as souvenirs and to prove to the French captain that Francois really had been in the camp of the Prussians. He helped himself to a rifle and a helmet, both of which he threw out into the garden. After a keen, sweeping glance about, the boy crawled out head first and let himself go. Francois nearly broke his [51] neck in the fall to the ground, landing as he did on his head and shoulders. For a moment he lay where he had fallen, then staggered to his feet, dizzy and a little weak from the jolt. He started away without, as yet, having a clear idea as to which was the right direction for him to take. The boy dodged from bush to bush and, reaching a hedge, bored his way through it and skulked along the other side of it, dragging the rifle behind him, the German helmet tightly clutched under one arm.

"'Where am I? Ah! The village is to the left. I must turn back and start again,' he decided. This was risky, but there seemed no other course for him to follow. Retracing his steps for some distance he finally struck off in the right direction. When he came in sight of the stream he discovered that the bridge was so far away that he could not hope to reach it without being discovered.

"'But Francois can swim,' he told himself. 'He shall yet fool the Prussians. Look [52] out! There they go!' German soldiers already were running toward the bridge, and he knew that his escape had been discovered. He believed, however, that he was far enough away so they would not see him.

"Francois swung the rifle over his shoulder and secured it there by its carrying strap, jammed the helmet tightly over his head and rolled down the bank into the river. The water was warm and the child was full of joy that he had outwitted his captors.

"Fortunately the river was not wide at this point, and on the opposite side was plenty of cover in the way of trees and bushes. But discovery came at about the time he reached the middle of the river. The sun, reflected from his bright metal helmet, had attracted the attention of the soldiers. A bullet splashed in the water to the right of him.

"'Huh!' he grunted. 'The Boches cannot shoot. Francois could shoot as good as that with his eyes shut. Bah! Shoot again.' [53] O-u-c-h! A bullet had gone through the helmet, so low that it raked the top of his head. It felt like a red-hot iron being drawn across the top of his head, and made his head swim dizzily.

"'It was a chance shot,' observed the boy. 'No Boche could shoot so true on purpose. I shall yet fool them.'

"Reaching the opposite shore he ran up the bank, not trying to conceal himself there. A bullet struck him in the shoulder, spun him around and laid him flat on the ground. He was on his feet almost instantly, shaking a fist at the Germans.

"'Shoot! I fear not your bullets,' he shouted. The boy then ran skulking from shrub to shrub until he reached the forest, into which he dashed. Both wounds were by now bleeding freely and his face was covered with blood from the scalp wound. He dashed on, not wholly certain of his direction, but, reaching the other side of the forest, found himself not far out of his way. From then on he trotted, keeping himself [54] up by sheer pluck, for he was getting weak.

"Francois saw nothing more of the enemy, and finally he staggered into his village. A sentry, recognizing the German helmet, halted him some distance away, and after questioning him sent the lad to the captain.

"'Here, monsieur le Capitaine, see what I have taken from the Boches,' he cried, upon espying the commander. 'Thick-heads, all of them! It is easy to fool the Boches.'

"'But, my boy, you are wounded. What has happened?' demanded the captain.

"'It is nothing; it was an accident. The Prussians hit me by mistake.'

"The officer called a surgeon and while the lad's wounds were being dressed Francois related to the captain all that he had seen in the Prussian camp.

"'And they plan to come here soon,' he added.

"'What makes you think that?' asked the commander.

[55] "'Because they have made the villagers stay in their homes. For what reason other than that do they wish to keep the villagers in? Again, they are fast making preparations to go into battle!'

"'You are a clever boy and a brave one,' cried the captain, enthusiastically. 'You may keep the rifle. You will be proud some day that you own it.'

"'I am proud now, monsieur le Capitaine, but I shall be more proud after you have whipped the Boches.'

"'That is good, but what can we do to reward you?'

"'Whip them quickly, that I may go to see my sick grandmother. I am much put out, sir, that I did not see her.'

"There was loud laughter at this, and at the earnest way in which it was said, but Francois never changed the sober expression of his face.

"'It shall be done. Reinforcements are coming and early this evening we shall go out to meet the Prussians. I promise you [56] that you shall soon see your grandmother, Francois.' And he did, for, acting upon his information, the French forces were enabled to inflict heavy losses upon the Germans and drive them from that part of the country. A few days later Francois made the trip again, and this time did see his dear grandmother, but she was not so ill but that she could work in her garden.

"And that, my dear little friends, is the story of another little hero of France," concluded Captain Favor.

"There are many like Francois among those youthful patriots," began Captain Favor when his little friends had gathered about him on another occasion to listen to stories about the Children of France. "They value neither their own safety nor their lives; they are willing and eager to make any sacrifice if by so doing they can serve their beloved France ever so little.

"One finds this spirit everywhere. It is one of the few bright and beautiful things to be found in the great world war, though many of the deeds of heroism of the French children will never be known. The little heroes have made the supreme sacrifice and their lips, sealed in death, can never tell of their deeds.

"That you may the better understand the spirit of patriotism that fills the hearts of all these little French children, I will tell you the story of little Pierre," said the captain. "This is not a long story, but a more heroic one never has been told.

"While Pierre was twelve he was small for his age, but sturdy, and he loved his country with a fervor that you children of America also should have in your hearts."

"We have," spoke up Joe Funk.

"Yes, I think that all of you have. I wish you to keep it, to keep the fires of patriotism burning and never let them grow dim. As for Pierre, I will now tell you of the noble sacrifices he made for France.

"Pierre lived with his mother in a small French village at the time the Germans entered the town. Being hungry, as usual, they intruded into the homes of the villagers and helped themselves to whatever they could find, in some instances after first demanding that food and money be turned [59] over to them. The villagers dared not disobey nor even raise a voice in protest.

"A captain and several men entered the home of little Pierre, where there was a wounded French sergeant that the lad's mother had been nursing and whom the little boy loved very dearly. The sergeant's wounds were just beginning to heal, but so weak was he that he could scarcely stand without someone to lean upon. When the Germans burst in the wounded man was filled with rage, but he knew better than to attempt to thwart them.

"'Give us food, all that you have. Hold back anything and you die," bellowed the Prussian captain, smiting the table with the flat of his saber.

"Pierre's mother was stout hearted. 'We have only bread and cheese,' she said. 'You may take it if you will, but I give not to a Prussian, not even so much as a crumb. Take it if you will, for you are strong while I am but a weak woman.'

"'Woman, you speak truly; we are [60] strong, and we shall take, but for this resistance you shall suffer. See what a Prussian does to such dogs of French as oppose him!'

"With that the captain struck Pierre's mother with the flat of his hand, hurling her clear across the room. She staggered against the wall and sank moaning to the floor.

"The captain evidently had overlooked the wounded French sergeant, who lay on a cot in the shadows, and his men were too fully occupied with helping themselves to food to take heed of anything else. As for little Pierre, the lad stood trembling with rage. He was not afraid, but he was filled with righteous indignation.

"The sergeant's eyes were blazing as he fixed his gaze on the face of the German captain.

"'You Prussian fiend!' shouted the sergeant.

"'What!' The captain wheeled like a flash.

"'For that you die! And ere the German could utter another word, the soldier leveled his revolver at the officer and fired. There followed a loud report, and Pierre's mother was avenged, for the Prussian captain lay dead on the floor.

"For a few seconds following the shot the Prussian soldiers stood mute, then, with one accord, they threw themselves upon the helpless sergeant who already had twice fired his revolver at them, but without effect. They beat him cruelly and dragged him out and before another captain, to whom they told the story of what had occurred in Pierre's home.

"The unfortunate sergeant was ordered to be taken to the village square, where a dozen old men of the village were being held by the Germans under sentence of death on the flimsy charge of having resisted the Prussians. One by one these unhappy Frenchmen were being lined up before a firing squad and shot down. The sergeant, who, of course, was to share a like fate, was [62] reserved for the last that he might have more time for fear to sink into his heart while watching the execution of the others. The sergeant neither asked for nor expected mercy. Well did he know what the penalty was for such an act as his, and he was willing to die for his country as well as for the sake of the woman who had nursed him through so many dark days of suffering.

"They tied him to a tree while engaged in their cruel work of shooting the accused old men, where the sergeant hung weak from loss of blood, for, under their rough handling his wounds had reopened.

"Little Pierre, his eyes large and troubled, had followed his friend to the square and stood sympathetically beside him.

"'What, can I do? Tell me quickly,' urged the boy.

"'Fetch me a cup of water. I am burning with the fever again. One drink of water and I shall have the strength to die [63] bravely. Those Prussian dogs shall not see so much as the quiver of an eyelid,' said the sergeant.

"Pierre slipped into a house and brought a cup of water which he placed at the lips of his friend. The sergeant had taken one swallow when a captain dashed the cup to the ground. He swung and struck Pierre a cruel blow across the cheek with the flat of his saber, laying the lad prostrate. Pierre staggered to his feet, eyes blazing, an angry red welt showing where he had been struck.

"'To give aid or comfort to the friends of France is to die!' hissed the German captain. 'For this you too shall die! But first you shall see how it goes with the others.'

"'I fear you not,' retorted the child, pluckily. 'I too can die for France with a brave heart, and so you shall die one day at the hands of my dear countrymen, but with a coward's heart.'

"'Ah! You are brave,' jeered the captain.

[64] "'I am a Frenchman,' answered Pierre, stoutly. 'A Frenchman does not fear to die.'

"'Good! For that I shall give you a chance to live and you shall come with us and fight for the Fatherland," declared the captain.

"'Bah! That for the Fatherland!' The lad snapped his fingers in the Prussian's face. Pierre's courage, instead of further angering the German, appeared to amuse him.

"'We shall see. It is for you to shoot your friend the sergeant. Shoot him and you shall have your freedom and your life. It is well that a Frenchman should be put to death by his own. Can you shoot?'

"'I can.'

"'Then here is a rifle. It is loaded. Shoot and shoot true and freedom is yours, for yourself and the old woman yonder who insulted the officer of my Emperor.' The captain extended the rifle, butt first, toward the boy. Pierre was outwardly calm, but [65] within his heart a storm was raging. Rather to the surprise of the spectators, he took the weapon, turned it over curiously in his hands, for it was the first German rifle he had handled, examined the mechanism of the lock, then raised his eyes to the motionless figure of the French sergeant.

"Pierre smiled and a new light sprang into his eyes.

"'Well?' demanded the captain impatiently. 'Do you shoot or do you die?'

"'I shoot!' cried the little French boy, his voice high pitched and shrill.

"Pierre turned like a flash and, raising the weapon, pointed it straight at the German captain and pulled the trigger.

"No report followed. The rifle had missed fire. And ere Pierre could make another try the weapon was snatched from his hands and a blow from the captain's fist again laid him low.

"'Dog!' raged the Prussian officer. 'Now you shall die, and yonder French sergeant shall be a witness to your punishment. Strip [66] the blinder from that man's eyes! Bind this boy!'

"'There is no need to bind me. I shall not run away. I am not afraid to die for France. I am sorry only that I did not kill you,' answered the lad stoutly. 'I am young—I can better be spared than others.'

"There was no reply to this, but the soldiers were ordered to lead the child out into the center of the square.

"'If you run you will be shot just the same,' warned the captain.

"'A Frenchman never runs away,' was the spirited retort.

"The firing squad took its place, eight men comprising the squad.

"'Make ready! Take aim!'

"Pierre faced them fearlessly, a smile on his face, his shoulders set well back, presenting a pathetic but brave little figure as he stood out there alone, facing death, but unafraid.

"'Fire!'

[67] "'Vive la France!' shouted the lad, waving his cap over his head.

"Eight rifles crashed in volley. And the little figure of brave Pierre crumpled down to the ground. He had died gloriously. He had died a man, despite his tender years.

"Wheeling, the squad dispatched the sergeant in the same way and their desperate work was finished."

The children were eagerly waiting to give the Captain a welcome when he limped out to meet his young friends on the lawn next morning. There were no tardy ones at these sittings, in fact so interested were they in the wonderful stories they were hearing, that they nearly always were ahead of time.

"We shall begin at once with a story that I know will thrill you all," said the Captain, as Joe Funk assisted him into his chair.

"The little hero that I shall tell you about today is one of the most remarkable of the child patriots of France. I think you will agree with me in that after you have heard the story.

"His name was Rene. Rene had been [70] with the army for some time, though he was only fourteen years old, making himself useful in many ways and fighting when he had the opportunity, which was more than seldom. For valiant service he had been made a corporal, so you may know he was brave and courageous, for the French do not encourage children to join their army, much less do they give them men's work and responsibilities.

"At the time to which I refer, the colonel of Rene's regiment had need of a man of courage and resource to carry certain important orders to the commanders in front-line trenches. This was early in the war when communication had not been worked out as scientifically as it has been since. For this duty the child offered his services.

"'This mission, I need not tell you, will prove a most perilous one,' warned the colonel.

"'I know it, my colonel. I am ready. I have but one life and that belongs to France.'

"'Bravely spoken. Now take careful heed to what I have to say to you so that you forget not the slightest detail of it.' Rene was then given final and detailed orders added to which was an urgent request to be careful of himself, for his own sake as well as for that of his country.

"After repeating his orders, showing that he had them well in mind, the lad left headquarters, his face radiant with joy at being entrusted with a mission such as this, a mission that would take him where he knew death would face him at every step. He had not far to go before reaching the zone of fire. Shells soon were bursting about him and machine-gun fire was sweeping the field with a perfect rain of steel.

"'Bang away all you like,' jeered the little fellow. 'Your voices I have heard before, but the French have stronger and more deadly voices than have you.'

"He finally arrived safely at the first trench. You understand he had been above ground all the time, while the fighters were [72] in the trenches, where they had more protection. It was the over-fire that he was obliged to plod through, and you who have never seen a battle do not realize what a fierce thing this over-fire is. His orders having been safely delivered, Rene proceeded on his troubled way to the trench where he was to deliver the second orders.

"The first part of this leg of the journey was more or less screened from the view of the enemy, but now a wide barren space, swept by shell fire, lay before him. It was almost certain death to venture into that open field. Rene knew it, but did not hesitate. It was not that he feared for his own life, but that he did not wish to lose it before he had fulfilled his mission.

"For better protection the lad dropped on hands and toes and ran along like a dog, thus far untouched by bullets, though they were thick as a nest of liberated bumble bees about his head.

"'The worst is about over now and I [73] shall soon be in the trenches,' he told himself encouragingly. He already could see the tops of the helmets of the soldiers in the trenches.

"A shell exploded close by at this juncture and a shell splinter struck him in the leg, leaving a wound. Rene rolled over on his back and grabbed the leg with both hands, then, with his first-aid bandage, bound the leg tightly above the wound so that he might not bleed to death. He was already much weakened from loss of blood.

"Having done all he could for himself, Rene started off again, dragging himself along with great effort, determined to reach the trench and deliver his orders, which he finally succeeded in doing.

"'You have been wounded. You shall not go on,' declared the commander after reading the orders and understanding fully what was still before the brave lad. 'You should go back to the hospital. I will send a man on to deliver the other orders.'

"'Monsieur le Capitaine, I have been [74] ordered to this duty. I must go on until I have fully obeyed my orders. Time enough for others to carry them after I am killed. But I shall not be—not until the orders are in the hands of the commanders in the trenches on this sector.'

"'You cannot walk; you have lost much blood,' protested the captain.

"'It matters not, sir; I can creep. That once was the only way I knew how to walk.'

"'Then go, my brave lad, and God be with you.'

"Rene saluted formally, though the effort of raising his hand sent shooting pains all through his body. He climbed laboriously from the trench and emerged into the bullet-swept plain once more. It was with a great effort that he even dragged himself along. He felt himself growing weaker with the moments. Every few yards he was compelled to lie over on his back for rest and to gain fresh strength for the next spurt. It required the most heroic courage for one in Rene's condition to go on. But he [75] grimly stuck to it, creeping wearily along.

"The end of the journey was now in sight, though the way still seemed long. No longer able to creep, the little messenger began to roll. It was slow progress and he suffered agonies, but every roll brought him that much nearer to his destination and the fulfillment of his mission. At last an officer in a front-line trench discovered him. Rene made a signal to the officer.

"Just then another huge shell struck the ground near the boy and burst with a terrific crash and roar that shook the earth for a long distance all about. The brave child was again hit by a splinter and this time mortally wounded. He knew that the end was near and his thoughts went back to his parents, to his home in the little village which he had left to go to war only a short time before.

"Rene roused himself with a supreme effort and again began to roll toward the trench.

"Stretcher bearers, observing his plight, [76] ran to his rescue, themselves unmindful of the storm of steel that was sweeping the plain back of the trenches. They tenderly picked the child up and bore him safely to the trench, where he was placed in a first-aid station in a bomb-proof dugout.

"'Tell monsieur le Capitaine that I have orders for him—important orders,' gasped the little soldier. 'Tell him to come quickly, for I shall not long be able to tell him what I have to say.'

"The captain, having been hurriedly summoned, hastened to the dugout. He gathered the dying lad tenderly in his arms, and, placing an ear close to the boy's lips, received from Rene the orders of the colonel, down to the last detail.

"The final word of these orders was Rene's last. He died in the arms of the captain, who tenderly laid him down.

"'Thus dies another hero of France,' murmured the officer, striding from the dugout, making no effort to hide the tears that were trickling down both cheeks.

"This little hero, my friends, offers a lesson in courage and devotion that each of you will do well always to remember," said Captain Favor in conclusion. "Tomorrow I shall tell you another story, if the weather permits of my coming out here. Au revoir, little friends."

"This time I will tell you about a quick-witted little French girl," said Captain Favor. "She was a stout-hearted little woman, full of spirit and as fearless as she was keen, as you shall see.

"It is not only the French lads who are quick-witted and brave. The girls are fully as much so, and all are filled with the same wonderful spirit of patriotism and love of country, as you you already have learned from the stories I have told you.

"This little woman's name was Jeanne; she had just turned eleven years when the incidents I am about to relate occurred. For some time the news had been coming to the village in which she lived of the wicked deeds of a company of German lancers. [80] These lancers were roving from village to village, stealing whatever they could lay their hands on, and mistreating the women and children. It was a terrible thing to do, but nothing new for the Prussians. As in other towns of which I have told you, all the able-bodied men of this village had gone to the war.

"To guard against surprise the inhabitants of Jeanne's home town had placed watchers on the outskirts of the village that the people might be notified in advance of the approach of the enemy's detachments.

"One afternoon the warning came, and, while expected, it was a shock to the people and their hearts were filled with fear. They closed and locked their doors, pulled down the shades and took refuge in their cellars. Not a person was to be seen in the streets; the village appeared to be deserted.

"'The Prussians are coming!' was the startling cry that had sent the inhabitants flying to the cellars, after which a great silence reigned in the little place.

"Soon after that a troop of Prussian lancers rode quietly into the village, alert for surprises, for they had confidently expected to see French soldiers ere this. Not a French soldier was in sight, so the invaders concluded there was nothing to fear. However, they decided to question some of the villagers.

"The house that Jeanne lived in was the first one the lancers came to. Jeanne, like others, had taken to the cellar with her parents, where they remained for a long time, tremblingly awaiting the arrival of their enemies. Not a sound thus far having been heard, the family wondered if the Prussians had come and gone. They fervently hoped this were true.

"'I will go and find out,' volunteered the little girl.

"'It is not safe,' objected the mother. 'If they are still here and should discover you, all would not be well with you, my daughter. You might be killed. I cannot permit it.'

"'Have no fears, mother; I will listen for every sound in the street and will go no further than the door. They shall neither see nor hear me.'

"The mother gave a reluctant consent and Jeanne crept upstairs, stepped quietly to the door and unbolted it, intending to open the door a few inches and peer out.

"At that instant the door was rudely forced open from the outside. A German officer and several men pushed their way in. The officer caught Jeanne in a listening attitude.

"'Halt!' he commanded, the lances of his men thrust out so close to the little girl that it seemed as if they already had pierced her. 'Listening, are you?'

"'Yes, monsieur,' she answered truthfully.

"'Why?'

"'That I might know if you had gone so I might once more go out to the street.'

"'You have nothing to fear if you tell us the truth. We would have certain information from you, child.'

"'Yes, monsieur.'

"'If you do not truthfully answer all my questions, you and all the rest will be shot.'

"'I do not fear you, sir. I will answer you well.'

"'Good. Then tell me, are there any French soldiers here?'

"'There are none here, sir.'

"'Neither here nor elsewhere in the village?'

"'There are none here, as I have said. I know not whether there are any in the village or not, for I have not seen any since a detachment passed through here two days ago.'

"'Is this the truth?'

"She looked at the officer with an expression of amazement that he should doubt her word.

"'Come, I will show you; I will prove to you that what I say is the truth.'

[84] "'It is well,' answered the Prussian officer, now reassured. 'We will pass on. It is good that you have not lied to us, child,' he said. 'It were better if all the French were so truthful, but, alas, they are not. Forward!'

"The Prussians departed, Jeanne watching them from the door. 'No, there are no French soldiers here,' she chuckled. 'Perhaps there may be just outside the village. And if so, alas for the Prussians!'

"A short distance beyond the village stood a large farmhouse in a vast yard, the latter being surrounded by a high stone wall. Within were trees and shade, so the place looking very attractive to the tired Prussians. Their commander ordered a halt and, opening the gate that led to the grounds, he ordered his men in for a rest. They tied their horses to trees and threw themselves down on the grass in great content.

"The place seemed deserted, but that some one was about was evidenced when the [85] gate through which they had entered was quietly closed and locked by no less a person than the little Jeanne herself. She had followed the Prussians at a distance, hoping to be able to give a signal to her friends if they might still be in the farmhouse, but, finding a better opportunity for serving them, had locked the lancers within the enclosure. Having done this, she ran as fast as her nimble feet would carry her for her own home.

"The tired lancers lay down to sleep while their commander strolled up to the house and beat on the door with the hilt of his saber. To his amazement the door was suddenly jerked open and a French dragoon dragged him in by the collar. The commander was a prisoner.

"A detachment of French soldiers were secreted in the house, where they had been waiting for some days for this very opportunity, knowing that the Prussians were headed that way. Yet, though the German commander had been deceived, little Jeanne [86] had not told him an untruth. She knew the French soldiers had been at the farmhouse three days before, for she had taken food to them, but she did not know of her own knowledge that they still were there. If she did not tell the officer the whole truth it was because he had not asked her, and for the sake of her beloved France she would not volunteer information that would aid the Germans.

"'Betrayed!' raged the Prussian when he saw how neatly he had been tricked. He groaned when a volley rang out from the house and several of his lancers fell.

"His men made a frantic rush for their horses; then, when they discovered that the gate was locked and that they were caught, they threw up their hands and surrendered to the foe that they had not yet seen.

"The French made every one of the lancers a prisoner. Several had been wounded, but none was killed.

"Credit was given to little Jeanne for placing the lancers in the hands of the [87] French soldiers, for had she not done this the French would have attacked the Prussians in the open and might have lost many men in the fight that would have followed.

"For her part in this fine capture little Jeanne in time received a letter from the President of the French Republic, thanking her in the name of France for her quick wit and for her heroism."

"You already have heard of some of the heroic little despatch bearers of France," said Captain Favor. "I shall now tell you of little Henri, one of the bravest and most resourceful of them all.

"Despatch carrying is a desperate business, all of it exposing the bearers to enemy fire at least part of the time, for most of the work of these brave men is in the open where the enemy can see them. Some go on foot, others on fast motorcycles. Ordinarily they travel in pairs, so that in case one be killed the other may take the message and hasten on with it to its destination. Henri, however, traveled alone.

"The Germans, at some distance from the principal battle line and at one end of it, [90] had advanced several miles into French territory, and, spreading out, had covered considerable ground. They were making themselves a nuisance, as they usually did, and a French force was sent in to drive them back. The French, too, had spread out and the officer in command, after becoming a little more familiar with conditions, had made his plans.

"'Now,' said the French colonel, 'what I wish is a man of undoubted courage, familiar with all this surrounding country, to carry letters to the commanders of our various units.'

"'I fear you will not find such a man,' answered one of his lieutenants. 'All the men of this section, of course, are fighting.'

"'Young Henri can do it,' suggested another officer.

"'A civilian who has been attached to the army unofficially for some few weeks.' Henri had made himself so useful that his presence with the army was not only permitted, [91] but welcomed. While he was but thirteen years of age, he was very strong, alert and active. The colonel told his aide to summon the boy so the commander might look him over.

"'Why do you follow the army?' demanded the colonel, after observing the boy critically.

"'Our home has been destroyed by the Germans, my father has been taken prisoner by them and my sisters have fled to other provinces,' he answered simply. 'That is why I am trying to serve my country in every way I can.'

"The colonel nodded approvingly.

"'It is a most important mission and a very dangerous one on which I must send a man. Do you think you can go through with it?'

"'Yes, sir.'

"'You may fall into the hands of the Prussians. In that event what would you do with the letters I shall entrust to your care?'

"'Swallow them, sir,' was the reply.

"'Good! You will do. You are a real Frenchman and while you are a mere child, I have full confidence that you will somehow manage to carry out my orders.'

"'I shall do my best, sir.'

"'That is all that any man can do. Give careful heed to what I tell you.' The colonel gave Henri careful instructions, after which he handed the letters to the lad and bade him God-speed.

"Henri set out quietly, slouching along with a carelessness not in keeping with his all-important mission. He was soon lost sight of in the undergrowth that covered many miles of territory in that section of the country, and that finally merged with a dense forest. The lad reasoned that the Germans would be found in this forest, as well as in the more open country, but somehow he must manage to get through their lines and reach the French on the other side. It was not an easy task, as he well knew, yet he was undaunted.

"He was following a course close to the edge of the forest when all at once he saw a Prussian soldier just outside the forest line. The boy plunged deeper into the woods and was unseen and unheard by the soldier, who evidently was a sentry.

"Later in the day Henri heard voices—German voices. By the sound he judged there must be a great many of them. He imagined he could hear commands.

"'I must be close to a nest of them,' he muttered. 'I must find out about those fellows, for the commanders will wish to know about them.' Creeping cautiously ahead he came to the edge of a clearing, a vast open space where the timber had, he judged, been cut off some time since, and the brush growth that followed the cutting of the trees had by now been well trampled down by the Germans, who appeared to be making this out-of-the-way place a sort of headquarters for their operations. He was amazed at what he saw.

"There, before Henri's eyes, was a small [94] German army, all branches of the service being represented. His association with the French Army enabled him to observe very closely and understand what he saw. And in this instance his observation told him that the Prussians were preparing for battle; he knew, too, that the orders he was carrying had to do with the very preparations he was witnessing. After fully satisfying his curiosity Henri plunged again into the forest, using great caution and watching keenly for stray Prussians. Finally he reached the brush again, being now free of the forest itself.

"'Halt!'

"The command brought him up standing. He rarely had been caught napping, but drew a breath of relief when he saw that the sentry who had halted him was in the uniform of his own army.

"'France!' was the boy's answer to the challenge. 'I have a letter for your commander.'

"'Pass!'

"Henri easily found his way to the commander's headquarters and delivered the letter intended for him.

"'You are going further?' questioned the officer.

"'Yes, sir. I have other orders to deliver.'

"'You had better watch closely that you are not captured,' warned the commander. 'The country through which you go is full of Prussians, and they are ugly. Be cautious.'

"Assuring the officer that he would use due caution, Henri went on his way, apparently without a care in the world. He was a most innocent appearing boy and it would be keen eyes indeed that would suspect him of being other than what he appeared, an irresponsible child.

"Henri now began to see German uniforms on all sides. They were increasing in numbers.

"'Henri never will get through, this with his letter,' grumbled the lad. 'I must act while there is yet time.' Crouching down [96] and watching the Prussians a few moments, he finally drew the remaining letter from his blouse; he read it carefully several times, read it until he had memorized every word of it. Having done this, the child tore the letter in bits and, munching them thoroughly, calmly swallowed them with a great gulp.

"'Ugh!' he grunted, making a wry face. 'That is not pleasant food, but if the Boches can read the letter now their eyes are sharp indeed. Henri carries his knowledge in his stomach. A queer place for knowledge, but a good place when there are Boches about. Now I shall be going.'

"He did not get far. The lad was halted shortly after leaving his cover. Germans sprang up on all sides of him. He saw that he had stumbled into a nest of them and that there was no escape.

"'What would you of me? I have done nothing,' cried the boy when he was roughly dragged before an officer. 'I go to my parents in yonder village.'

"'Is it for that that you crawl along and hide yourself as a spy?' demanded the officer sternly.

"'I saw the soldiers and I was afraid,' he whimpered.

"'Take him away!' ordered the officer.

"'Take me where? You can see I have nothing. I am but a poor peasant boy who could do no harm even if he would.'

"'You are shamming. You are a spy and you should be shot. Search him!' commanded the officer.

"They stripped the child, Henri, during the operation, weeping bitterly, but such tears as he shed were forced, yet they appeared real to the onlookers. His clothing was very thoroughly searched, the soldiers even tearing out the lining of his blouse and ripping his necktie apart to make certain that no despatches were concealed in them. Of course, they found nothing.

"'You see, I have told the truth,' he whimpered, now addressing the officer. 'Please let me go to my parents.'

"The officer laughed harshly.

"'Lock him up. He is a fraud, and we shall yet find him to be such. The French resort to many tricks.'

"Henri was placed in charge of a soldier, by whose side he trudged along, wiping his eyes frequently, apparently in great distress of mind, as a boy naturally would be in his situation. Henri's eyes were red, but they were red from rubbing rather than from the tears they had shed, and were keenly on the alert; they missed nothing of what was going on about them. He did not know where they proposed to take him, but wherever it was he determined not to go, for the letter in his stomach was a constant reminder of what was expected of him.

"There was much activity about them; it was a busy scene, and Henri's guard was plainly interested in it—he was becoming more interested in the activity than he was in his prisoner, which fact did not escape the lad, who appeared to be so filled with despair.

"Soldier and prisoner finally came to the bank of a canal, along which they walked, the soldier still watching the movements of the troops. Now Henri saw his opportunity.

"All at once he sprang away from his guard, and, taking a long leap, plunged head first into the canal. He dove deep and shot himself half way across before coming to the surface.

"The soldier guard stood stupefied for a moment. Recovering his wits, he began to shoot at the bobbing head of Henri that was now out of the water then under it.

"Henri, by this time, was rapidly nearing the opposite bank of the canal, taking little heed of the bullets that were splashing all about him.

"'It is good luck to be little,' he chuckled as he scrambled up the bank and dashed into the bushes. Bullets were singing all about him now, showing that several soldiers had joined in the shooting, but the plucky boy was not hit, though there were [100] bullet holes in his jacket and two through his cap.

"'Good bye, Mr. Boche,' he called back. 'Henri thanks you that you did not hit him in the place where he carries his orders.' He then ran swiftly over the remaining few miles that lay between him and his destination. Reaching the French lines safely, he was led to the commander of the detachment in his home village.

"'I have orders for you, sir,' he said, saluting the commander.

"'Very good. Where are they?'

"'In my stomach, sir.'

"The officer was puzzled for the moment, then he began to laugh. Henri related the circumstances that had made necessary the destruction of the letter, and at his dictation the commander wrote down the orders, which the lad repeated to him exactly as they had been written in the letter. Henri's mission had been faithfully carried out.

"'France has need of such as you,' said [101] the commander approvingly. 'What shall you do now?'

"'I must return to my troops and make my report to my commanding officer,' was the simple reply. 'I shall wait for the night before starting, for the Boches this time cannot be so easily fooled. Remember, I still have the orders in my stomach. Would it not be sad if the Boches discovered them and took them from me?' Henri grinned and the commander laughed heartily.

"Henri's return journey was made without disaster, though several times he narrowly missed being captured. Late on the following morning the plucky boy reached his regiment and made his report to his colonel, who warmly commended the child for his patriotism and courage."