This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: "Forward, March"

A Tale of the Spanish-American War

Author: Kirk Munroe

Release Date: July 7, 2005 [eBook #16231]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK "FORWARD, MARCH"***

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | A BOWL OF ROSES |

| II. | WAR IS DECLARED |

| III. | ROLLO THE TERROR |

| IV. | THE ROUGH RIDERS AT SAN ANTONIO |

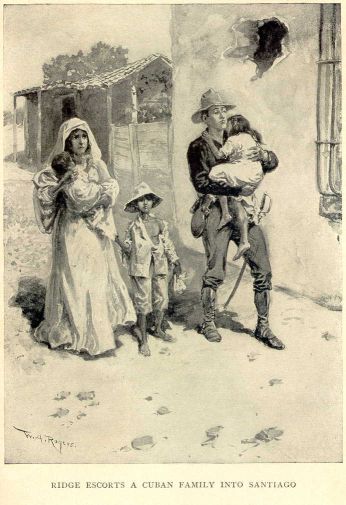

| V. | RIDGE BECOMES A TROOPER |

| VI. | OFF FOR THE WAR |

| VII. | THE STORY OF HOBSON AND THE MERRIMAC |

| VIII. | CHARGED WITH A SECRET MISSION |

| IX. | HERMAN DODLEY INTERPOSES DIFFICULTIES |

| X. | ON THE CUBAN BLOCKADE |

| XI. | A LIVELY EXPERIENCE OF CUBAN HOSPITALITY |

| XII. | DENOUNCED BY A FRIEND |

| XIII. | TO BE SHOT AT SUNRISE |

| XIV. | REFUGEES IN THE MOUNTAINS |

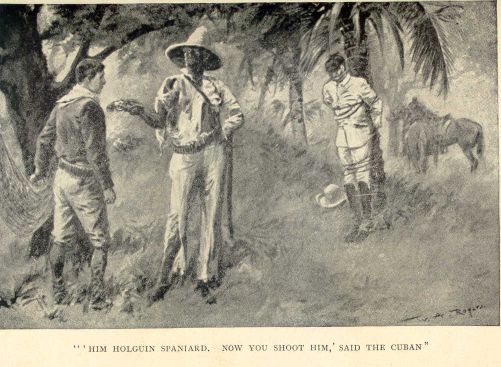

| XV. | DIONYSIO CAPTURES A SPANIARD |

| XVI. | ASLEEP WHILE ON GUARD |

| XVII. | IN THE HANDS OF SPANISH GUERILLAS |

| XVIII. | DEATH OF SEÑORITA |

| XIX. | CALIXTO GARCIA THE CUBAN |

| XX. | THE TWO ADMIRALS |

| XXI. | A SPANIARD'S LOYALTY |

| XXII. | ROLLO IN CUBA |

| XXIII. | THE "TERRORS" IN BATTLE |

| XXIV. | FACING SAN JUAN HEIGHTS |

| XXV. | RIDGE WINS HIS SWORD |

| XXVI. | MUTINY ON A TRANSPORT |

| XXVII. | DESTRUCTION OF THE SPANISH SHIPS |

| XXVIII. | LAST SHOT OF THE CAMPAIGN |

| XXIX. | TWO INVALID HEROES |

| XXX. | ROLLO MAKES PROPOSITIONS |

In the morning-room of a large, old-fashioned country-house, situated a few miles outside the city of New Orleans, sat a young man arranging a bowl of roses. Beside him stood a pretty girl, in riding costume, whose face bore a trace of petulance.

"Do make haste, Cousin Ridge, and finish with those stupid flowers. You have wasted half an hour of this glorious morning over them already!" she exclaimed.

"Wasted?" rejoined Ridge Norris, inquiringly, and looking up with a smile. "I thought you were too fond of flowers to speak of time spent in showing them off to best advantage as 'wasted.'"

"Yes, of course I'm fond of them," answered Spence Cuthbert, who was from Kentucky on a Mardi Gras visit to Dulce Norris, her school-chum and cousin by several removes, "but not fond enough to break an engagement on account of them."

"An engagement?"

"Certainly. You promised to go riding with me this morning."

"And so I will in a minute, when I have finished with these roses."

"But I want you to come this instant."

"And leave a duty unperformed?" inquired Ridge, teasingly.

"Yes; now."

"In a minute."

"No. I won't wait another second."

With this the girl flung herself from the room, wearing a very determined expression on her flushed face.

Ridge rose to follow her, and then resumed his occupation as a clatter of hoofs on the magnolia-bordered driveway announced the arrival of a horseman.

"She won't go now that she has a caller to entertain," he said to himself.

But in this he was mistaken; for within a minute another clatter of hoofs, mingled with the sound of laughing voices, gave notice of a departure, and, glancing from an open window, Ridge saw Spence Cuthbert ride gayly past in company with a young man whose face seemed familiar, but whose name he could not recall.

As they swept by both looked up laughing, while the horseman lifted his hat in a bow that was almost too sweeping to be polite.

"What did you say Ridge was doing?" he asked, as they passed beyond earshot.

"Arranging a bowl of roses," answered Spence.

"Nice occupation for a man," sneered the other. "And he preferred doing that to riding with you?"

"So it seems."

"Well, I am not wholly surprised, for, as I remember him, he was a soft-hearted, Miss Nancy sort of a boy, who was always coddling sick kittens, or something of the kind, and never would go hunting because he couldn't bear to kill things. He apparently hadn't a drop of sporting blood in him, and I recall having to thrash him on one occasion because he objected to my shooting a bird. I thought of course, though, that he had outgrown all such nonsense by this time."

"There is no nonsense about him!" flashed out Spence, warmly; and then, to her companion's amazement, the girl began a most spirited defence of her absent cousin, during which she denounced in such bitter terms the taking of innocent lives under the name of "sport" that the other was finally thankful to change the conversation to a more congenial topic.

In the mean time Dulce Norris had entered the morning-room to find out why Spence had gone to ride with Herman Dodley instead of with Ridge, as had been arranged.

"Was that Herman Dodley?" asked the latter, without answering his sister's question.

"Yes, of course, but why do you ask with such a tragic air?"

"Because," replied Ridge, "I have heard reports concerning him which, if confirmed, should bar the doors of this house against him forever."

"What do you mean, Ridge Norris? I'm sure Mr. Dodley bears as good a reputation as the majority of young men one meets in society. Of course since he has got into politics his character has been assailed by the other party; but then no one ever believes what politicians say of one another."

"No matter now what I mean," rejoined the young man. "Perhaps I will tell you after I have spoken to father on the subject, which I mean to do at once."

Ridge Norris, on his way to the library, where he hoped to find his father, was somewhat of a disappointment to his family. Born of a mother in whose veins flowed French and Spanish blood, and who had taught him to speak both languages, and of a New England father, who had spent his entire business life in the far South, Ridge had been reared in an atmosphere of luxury. He had been educated in the North, sent on a grand tour around the world, and had finally been given a position, secured through his father's influence, in a Japanese-American banking house. From Yokohama he had been transferred to the New York office, where, on account of a slight misunderstanding with one of his superiors, he had thrown up his position to return to his home only a few days before this story opens.

Now his family did not know what to do with him. He disliked business, and would not study for a profession. He was a dear, lovable fellow, honest and manly in all his instincts; but indolent, fastidious in his tastes, and apparently without ambition. He was devoted to music and flowers, extremely fond of horses, which he rode more than ordinarily well, and had a liking for good books. He had, furthermore, returned from his travels filled with pride for his native land, and declaring that the United States was the only country in the world worth fighting and dying for.

Taking the morning's mail from the hand of a servant who had just brought it, Ridge entered his father's presence.

"Here are your letters, sir," he said, "but before you read them I should like a few moments' conversation with you."

"Certainly, son. What is it?"

As Ridge told what he had heard concerning Herman Dodley, the elder man's brows darkened; and, when the recital was finished, he said:

"I fear all this is true, and have little doubt that Dodley is no better than he should be; but, unfortunately, I am so situated at present that I cannot forbid him the house. I will warn Dulce and her friend against him; but just now I am not in a position to offend him."

"Why, father!" cried Ridge, amazed to hear his usually fearless and self-assertive parent adopt this tone. "I thought that you were--"

"Independent of all men," interrupted the other, finishing the sentence. "So I believed myself to be. But I am suddenly confronted by business embarrassments that force me temporarily to adopt a different policy. Truly, Ridge, we are threatened with such serious losses that I am making every possible sacrifice to try and stem the tide. I have even placed our summer home on the Long Island coast in an agent's hands, and am deeply grieved that you should have thrown up a position, promising at least self-support, upon such slight provocation."

"But he ordered me about as though I were a servant, instead of requesting me to do things in a gentlemanly way."

"And were you not a servant?"

"No, sir, I was not--at least, not in the sense of being amenable to brutal commands. I was not, nor will I ever be, anybody's slave."

"Oh well, my boy!" replied the elder, with a deep sigh, "I fear you will live to discover by sad experience that pride is the most expensive of earthly luxuries, and that one must consent to obey orders long before he can hope to issue commands. But we will discuss your affairs later, for now I must look over my letters."

While Mr. Norris was thus engaged, Ridge opened the morning paper, and glanced carelessly at its headlines. Suddenly he sprang to his feet with a shout, his dark face glowing and his eyes blazing with excitement.

"By heavens, father!" he cried, "the United States battle-ship Maine has been blown up in Havana Harbor with a loss of two hundred and sixty of her crew. If that doesn't mean war, then nothing in the world's history ever did. You needn't worry about me any more, sir, for my duty is clearly outlined."

"What do you propose to do?" asked the elder man, curiously. "Will you try to blow up a Spanish battle-ship in revenge?"

"No, sir. But I shall enlist at the very first call to arms, and offer my life towards the thrashing of the cowards who have perpetrated this incredible crime."

Thrilled to the core by the momentous news he had just read, Ridge hastened to impart it to his mother and sister. At the same time he ordered a horse on which he might ride to the city for further details of the stupendous event. As he was about to depart, Spence Cuthbert and her escort, returning from their ride, dashed up to the doorway.

"Have you heard the news?" cried Ridge, barely nodding to Dodley.

"Yes," replied Spence. "Isn't it dreadful? Mr. Dodley told me all about it, and after hearing it I couldn't bear to ride any farther, so we came back."

"I wish he had told me before you started," said Ridge, "so that I might have been in the city long ago."

"You were so busily and pleasantly engaged with your roses that I hesitated to interrupt you," murmured Herman Dodley. "Now, however, if I can be of any assistance to you in the city, pray consider me at your service."

"Can you assist me, sir, to obtain a commission in the army that will be summoned to visit a terrible punishment upon Spain for her black treachery?"

"Undoubtedly I could, and of course I would do so with pleasure if the occasion should arise. But there won't be any war. The great Yankee nation is too busy accumulating dollars to fight over a thing of this kind. We will demand a money indemnity, it will be promptly paid, and the whole affair will quickly be forgotten."

"Sir!" cried Ridge, his face pale with passion. "The man who utters such words is at heart a traitor to his country."

"If it were not for the presence of ladies, I would call you to account for that remark," muttered Dodley. "As it is, I shall not forget it. Ladies, I have the honor to wish you a very good-morning."

With this the speaker, who had not dismounted, turned his horse's head and rode away.

Never was the temper and patience of the American people more sorely tried than by the two months of waiting and suspense that followed the destruction of their splendid battle-ship. The Maine had entered Havana Harbor on a friendly visit, been assigned to a mooring, which was afterwards changed by the Spanish authorities, and three weeks later, without a suspicion of danger having been aroused or a note of warning sounded, she was destroyed as though by a thunder-bolt. It was nearly ten o'clock on the night of Tuesday, February 15th. Taps had sounded and the crew were asleep in their hammocks, when, by a terrific explosion, two hundred and fifty-eight men and two officers were hurled into eternity, sixty more were wounded, and the superb battle-ship was reduced to a mass of shapeless wreckage.

It was firmly believed throughout the United States that this appalling disaster was caused by a submarine mine, deliberately placed near the mooring buoy to which the Maine had been moved, to be exploded at a favorable opportunity by Spanish hands.

The Spaniards, on the other side, claimed and strenuously maintained that the only explosion was that of the ship's own magazines, declaring in support of this theory that discipline on all American men-of-war was so lax as to invite such a catastrophe at any moment.

To investigate, and settle if possible, this vital question, a Court of Inquiry, composed of four prominent naval officers, was appointed. They proceeded to Havana, took volumes of testimony, and, after six weeks of most searching investigation, made a report to the effect that the Maine was destroyed by two distinct explosions, the first of which was that of a mine located beneath her, and causing a second explosion--of her own magazines--by concussion.

During these six weeks the country was in a ferment. For three years war had raged in Cuba, where the natives were striving to throw off the intolerable burden of Spanish oppression and cruelty. In all that time the sympathies of America were with the struggling Cubans; and from every State of the Union demands for intervention in their behalf, even to the extent of going to war with Spain, had grown louder and more insistent, until it was evident that they must be heeded. With the destruction of the Maine affairs reached such a crisis that the people, through their representatives in Congress, demanded to have the Spanish flag swept forever from the Western hemisphere.

In vain did President McKinley strive for a peaceful solution of the problem; but with both nations bent on war, he could not stem the tide of popular feeling. So, on the 20th of April he was obliged to demand from Spain that she should, before noon of the 23d, relinquish forever her authority over Cuba, at the same time withdrawing her land and naval forces from that island. The Spanish Cortes treated this proposition with contempt, and answered it by handing his passports to the American Minister at Madrid, thereby declaring war against the great American republic.

At this time Spain believed her navy to be more than a match for that of the United States, and that, with nearly two hundred thousand veteran, acclimated troops on the island of Cuba, she was in a position to resist successfully what she termed the "insolent demands of the Yankee pigs."

On this side of the Atlantic, Congress had appropriated fifty millions of dollars for national defence, the navy was being strengthened by the purchase of additional ships at home and abroad, fortifications were being erected along the entire coast, harbors were mined, and a powerful fleet of warships was gathered at Key West, the point of American territory lying nearest the island of Cuba.

Then came the President's call for 125,000 volunteers, followed a few weeks later by a second call for 75,000 more. This was the summons for which our young friend, Ridge Norris, had waited so impatiently ever since that February morning when he had arranged a bowl of roses and read the startling news of the Maine's destruction.

No one in all the country had been more impatient of the long delay than he; for it had seemed to him perfectly evident from the very first that war must be declared, and he was determined to take an active part in it at the earliest opportunity. His father was willing that he should go, his mother was bitterly opposed; Dulce begged him to give up his design, and even Spence Cuthbert's laughing face became grave whenever the subject was mentioned, but the young man was not to be moved from his resolve.

Mardi Gras came and passed, but Ridge, though escorting his sister and cousin to all the festivities, took only a slight interest in them. He was always slipping away to buy the latest papers or to read the bulletins from Washington.

"Would you go as a private, son?" asked his father one evening when the situation was being discussed in the family circle.

"No, no! If he goes at all--which Heaven forbid--it must be as an officer," interposed Mrs. Norris, who had overheard the question.

"Of course a gentleman would not think of going as anything else," remarked Dulce, conclusively.

"I believe there were gentlemen privates on both sides during the Civil War," said Spence Cuthbert, quietly.

"Of course," admitted Dulce, "but that was different. Then men fought for principles, but now they are going to fight for--for--"

"The love of it, perhaps," suggested the girl from Kentucky.

"You know I don't mean that," cried Dulce. "They are going to fight because--"

"Because their country calls them," interrupted Ridge, with energy, "and because every true American endorses Decatur's immortal toast of 'Our Country. May she always be in the right; but, right or wrong, our country.' Also because in the present instance we believe it is as much our right to save Cuba from further oppression at the hands of Spain as it always is for the strong to interpose in behalf of the weak and helpless. For these reasons, and because I do not seem fit for anything else, I am going into the city to-morrow to enlist in whatever regiment I find forming."

"Oh, my boy! my boy!" cried Mrs. Norris, flinging her arms around her son's neck, "do not go tomorrow. Wait a little longer, but one week, until we can see what will happen. After that I will not seek further to restrain you. It is your mother who prays."

"All right, mother dear, I will wait a few days to please you, though I cannot see what difference it will make."

So the young man waited as patiently as might be a week longer, and before it was ended the whole country was ringing with the wonderful news of Admiral George Dewey's swift descent upon the Philippine Islands with the American Asiatic squadron. With exulting heart every American listened to the thrilling story of how this modern Farragut stood on the bridge of the Olympia, and, with a fine contempt for the Spanish mines known to be thickly planted in the channel, led his ships into Manila Bay. Almost before the startled Spaniards knew of his coming he had safely passed their outer line of defences, and was advancing upon their anchored fleet of iron-clad cruisers. An hour later he had completely destroyed it, silenced the shore batteries, and held the proud city of Manila at his mercy. All this he had done without the loss of a man or material damage to his ships, an exploit so incredible that at first the world refused to believe it.

To Ridge Norris, who had spent a week in the Philippines less than a year before, the whole affair was of intense interest, and he bitterly regretted not having remained in the Far East that he might have participated in that glorious fight.

"I would gladly have shipped as a sailor on the Olympia if I had only known what was in store for her!" he exclaimed; "but a chance like that, once thrown away, never seems to be offered again."

"But, my boy, it is better now," said Mrs. Norris, with a triumphant smile. "Then you would have been only a common seaman; one week ago you would have enlisted as a common soldier. Now you may go as an officer--what you will call a lieutenant--with the chance soon to become a captain, and perhaps a general. Who can tell?"

"Whatever do you mean, mother?"

"What I say, and it is even so; for have I not the promise of the Governor himself? But your father will tell you better, for he knows what has been done."

So Ridge went to his father, who confirmed what he had just heard, saying:

"Yes, son; your mother has exerted her influence in your behalf, and procured for you the promise of a second-lieutenant's commission, provided I am willing to pay for the honor."

"How, father?"

"By using my influence to send Herman Dodley to the Legislature as soon as he comes back from the war."

"Is Dodley going into the army?"

"Yes. He is to be a major."

"And would you help to send such a man to the Legislature?"

"If you wanted to be a lieutenant badly enough to have me do so, I would."

"Father, you know I wouldn't have you do such a thing even to make me President of the United States!"

"Yes, son, I know it."

And the two, gazing into each other's eyes, understood each other perfectly.

"I would rather go as a private, father."

"I would rather have you, son; though it would be a great disappointment to your mother."

"She need not know, for I will go to some distant camp before enlisting. I wouldn't serve in the same regiment with Herman Dodley, anyhow."

"Of course not, son."

"I suppose his appointment is political--as well as the one intended for me?"

"Yes; and so it is with every other officer in the regiment."

"That settles it. I would sooner join the Cubans than fight under the leadership of mere politicians. So, when I do enlist, it will be in some regiment where the word politics is unknown, even if I have to go into the regular army."

"Son, I am prouder of you than I ever was before. What will you want in the way of an outfit?"

"One hundred dollars, if you can spare so much."

"You shall have it, with my blessing."

So it happened that, a few days later, Ridge Norris started for the war, though without an idea of where he should find it or in what capacity he should serve his country.

On the evening when Ridge decided to take his departure for the seat of war he was driven into the city by his father, who set him down near the armory of the regiment in which he had been offered a lieutenant's commission--for a consideration.

"I don't want you to tell me where you are going, son," said Mr. Norris, "for I would rather be able to say, with a clear conscience, that I left you at headquarters, and beyond that know nothing of your movements."

"All right, father," replied the young fellow. "I won't tell you a thing about it, for I don't know where I am going any more than you do."

"Then good-bye, my boy, and may Almighty God restore you to us safe and well when the war is over. Here is the money you asked for, and I only wish I were able to give you ten times the sum. Be careful of it, and don't spend it recklessly, for you must remember that we are poor folk now."

Thus saying, the elder man slipped a roll of crisp bills into his son's hand, kissed him on the cheek, a thing he had not done before in a dozen years, and, without trusting his voice for another word, drove rapidly away.

For a minute Ridge stood in the shadow of the massive building, listening with a full heart to the rattle of departing wheels. Then he stooped to pick up the hand-bag, which was all the luggage he proposed to take with him. As he did so, two men brushed past him, and he overheard one of them say:

"Yes, old Norris was bought cheap. A second-lieutenancy for his cub fixed him. The berth'll soon be vacant again though, for the boy hasn't sand enough to--"

Here the voice of the speaker was lost as the two turned into the armory.

"Thanks for your opinion, Major Dodley," murmured Ridge; "that cheap berth will be vacant sooner than you think."

Then, picking up his "grip," the young fellow walked rapidly away towards the railway station. He was clad in a blue flannel shirt, brown canvas coat, trousers, and leggings, and wore a brown felt hat, the combination making up a costume almost identical with that decided upon as a Cuban campaign uniform for the United States army. Ridge had provided himself with it in order to save the carrying of useless luggage. In his "grip" he had an extra shirt, two changes of under-flannels, several pairs of socks, a pair of stout walking-shoes, and a few toilet articles, all of which could easily be stowed in an army haversack.

Our hero's vaguely formed plan, as he neared the station, was to take the first east-bound train and make his way to one of the great camps of mobilization, either at Chickamauga, Georgia, or Tampa, Florida, where he hoped to find some regiment in which he could conscientiously enlist. A train from the North had just reached the station as he entered it; but, to his disgust, he found that several hours must elapse before one would be ready to bear him eastward.

He was too excited to wait patiently, but wandered restlessly up and down the long platform. All at once there came to his ears the sound of a familiar voice, and, turning, he saw, advancing towards him, in the full glare of an electric light, three men, all young and evidently in high spirits. One, thin, brown, and wiry, was dressed as a cowboy of the Western plains. Another, who was a giant in stature, wore a golf suit of gray tweed; while the third, of boyish aspect, whom Ridge recognized as the son of a well-known New York millionaire, was clad in brown canvas much after his own style, though he also wore a prodigious revolver and a belt full of cartridges.

He was Roland Van Kyp, called "Rollo" for short, one of the most persistent and luxurious of globe-trotters, who generally travelled in his own magnificent steam-yacht Royal Flush, on board of which he had entertained princes and the cream of foreign nobility without number. Everybody knew Van Kyp, and everybody liked him; he was such a genial soul, ever ready to bother himself over some other fellow's trouble, but never intimating that he had any of his own; reckless, generous, happy-go-lucky, always getting into scrapes and out of them with equal facility. To his more intimate friends he had been variously known as "Rollo Abroad," "Rollo in Love," "Rollo in Search of a Wife," or "Rollo at Play," and when Ridge became acquainted with him in Yokohama he was "Rollo in Japan."

He now recognized our hero at a glance, and sprang forward with outstretched hand.

"Hello, Norris, my dear boy!" he cried. "Whatever brings you here? Thought you were still far away in the misty Orient, doing the grand among the little brown Japs, while here you are in flannel and canvas as though you were a major-general in the regular army. What does it mean? Are you one of us? Have you too become a man of war, a fire-eater, a target for Mausers? Have you enlisted under the banner of the screaming eagle?"

"Not yet," laughed Ridge, "but I am on my way East to do so in the first regiment uncontaminated by politics that I can find."

"Then, old man, you don't want to go East. You want to come West with us. There is but one regiment such as you have named, and it is mine; for, behold! I am now Rollo in the Army, Rollo the Rough Rider, Rollo the Terror. Perhaps it would be more becoming, though, to say 'Ours,' for we are all in it."

"I should rather imagine that it would," growled he of the golf stockings, now joining in the conversation. "And, 'Rollo in Disguise,' suppose you present us to your friend; for, if I am not mistaken, he is a gentleman of whom I have heard and would like much to meet."

"Of course you would," responded Rollo, "and I beg your pardon for not having introduced you at once; but in times of war, you know, one is apt to neglect the amenities of a more peaceful existence. Mr. Norris, allow me to present my friend and pupil in the art of football-playing--"

"Oh, come off," laughed the big man.

"Pupil, as I was saying when rudely interrupted," continued Rollo, "Mr. Mark Gridley."

"Not Gridley, the famous quarter-back!" exclaimed Ridge, holding out his hand.

"That's him," replied Van Kyp.

"And aren't you Norris, the gentleman rider?" asked Gridley.

"I have ridden," acknowledged Ridge.

"So has this my other friend and fellow-soldier," cried Van Kyp. "Norris, I want you to know Mr. Silas Pine, of Medora, North Dakota, a bad man from the Bad Lands, a bronco-buster by profession, who has also consented to become a terror to Spaniards in my company."

"Have you a company, then?" asked Ridge, after he had acknowledged this introduction.

"I have--that is, I belong to one; but, in the sense you mean, you must not use the word company. That is a term common to 'doughboys,' who, as you doubtless know, are merely uniformed pedestrians; but we of the cavalry always speak of our immediate fighting coterie as a 'troop.' Likewise the 'battalion' of the inconsequent doughboy has for our behoof been supplanted by the more formidable word 'squadron,' to show that we are de jure as well as de facto men of war. Sabe?"

"Then you are really in the cavalry?" asked Ridge, while laughing at this nonsense.

"Yes, I really am, or rather I really shall be when I get there; for though enlisted and sworn in, we haven't yet joined or been sworn at."

"What is your regiment?"

"You mean our 'command.' Why, didn't I tell you? 'Teddy's Terrors,' Roosevelt's Rough Riders. First Volunteer Cavalry, U.S.A., Colonel Leonard Wood commanding."

"The very one!" cried Ridge. "Why didn't I think of it before? How I wish I could join it."

"And why not?"

"I thought there were so many applications that the ranks were more than full."

"So there may be, but, like lots of other full things, there's always room for one more, if he's of the right sort."

"Do you imagine I would stand the slightest chance of getting in?"

"I should say you would. With me ready to use my influence in your behalf, and me and Teddy the chums we are, besides you being the rider you are. Why the first question Teddy asks of an applicant is 'Can you ride a horse?' And when you answer, 'Sir, I am the man who wrote--I mean who won the silver hurdles at the last Yokohama gym.', he'll be so anxious to have you in the regiment that he'd resign in your favor rather than lose you. Oh, if I only had your backing do you suppose I'd be a mere private Terror? No, siree, I'd be corporal or colonel or something of that kind, sure as you're born. But come on, let's get aboard, for there's the tinkle-bell a-tinkling."

"I haven't bought my ticket yet," remonstrated Ridge.

"You won't need one, son. We're travelling in my private car 'Terror'--used to be named 'Buster,' you know--and the lay-out is free to all my friends."

Thus it happened that kindly Fate had interposed to guide our hero's footsteps, but it was not until he found himself seated in the luxurious smoking-room of Rollo Van Kyp's private railway carriage that it occurred to him to inquire whither they were bound.

"To the plains of Texas, my boy, and the city of San Antonio de Bexar, where Teddy and his Terrors are impatiently awaiting our advent," replied Rollo. At the same time he touched an electric bell and ordered a supper, which, when it appeared, proved to be one of the daintiest meals that Ridge Norris had ever eaten.

During the remainder of that night and all the following day the train to which the "Terror" was attached sped westward through the rich lowlands of southern Louisiana and across the prairies of Texas. It crossed the tawny flood of the Mississippi on a huge railway ferry to Algiers, and at New Iberia it passed a side-tracked train filled with State troops bound for Baton Rouge. Early the next morning at Houston, Texas, it drew up beside another train-load of soldiers on their way to Austin. To the excited mind of our young would-be cavalryman it seemed as though the whole country was under arms and hurrying towards the scene of conflict. Was he not going in the wrong direction, after all? And would not those other fellows get to Cuba ahead of him in such force that there would be no Spaniards left for the Riders to fight? This feeling was so increased upon reaching the end of the journey, where he saw two San Antonio companies starting for the East, that he gave expression to his fears, whereupon Van Kip responded, promptly:

"Don't you fret, old man. We'll get there in plenty of time. Teddy's gone into this thing for blood, and he's got the inside track on information, too. Fixed up a private ticker all of his own before he left Washington, and when he gets ready to start he'll go straight to the front without a side-track. Oh, I know him and his ways! for, as I've said before, we're great chums, me and Teddy. I shouldn't wonder if he'd be at the station to meet us."

To Rollo's disappointment, neither Lieutenant-Colonel Roosevelt nor any one else was on hand to welcome the Riders' new recruits, but this was philosophically explained by the young New-Yorker on the ground that he had thoughtlessly neglected to telegraph their coming. Being thus left to their own devices, and anxious to join their regiment as quickly as possible, the three who were already enlisted engaged a carriage to convey them to the fair-grounds, just beyond the city limits, where the Riders were encamped, leaving Ridge to occupy the car in solitary state until morning.

"You just stay here and make yourself cozy," said Rollo, "while we go and get our bearings. I'll see Teddy and fix things all right for you, so that you can come out and join us bright and early tomorrow. So long. Robert, take good care of Mr. Norris, and see that he has everything to make him comfortable."

This order was delivered to the colored steward of the car, and in another minute the excited trio had rattled away, leaving Ridge to a night of luxurious loneliness.

To occupy his time he took a brisk walk into the city, and reached the Alamo Plaza before he knew where he was. Then, suddenly, he realized; for, half-hidden by a great ugly wooden building, used as a grocery-store, he discovered an antiquated, half-ruinous little structure of stone and stucco that he instantly recognized, from having seen it pictured over and over again. It was the world-renowned Alamo, one of the most famous monuments to liberty in America; and, hastening across the plaza, Ridge stood reverently before it, thrilled with the memory of Crockett and Bowie, Travis and Bonham, who, more than half a century before, together with their immediate band of heroes, here yielded up their lives that Texas might be free.

Ridge was well read in the history of the Lone Star State, and now he strove to picture to himself the glorious tragedy upon which those grim walls had looked. As he thus stood, oblivious to his surroundings, he was recalled to them by a voice close at hand, saying, as though in soliloquy:

"What a shame that so sacred a monument should be degraded by the vulgarity of its environment!"

"Is it not?" replied Ridge, turning towards the speaker. The latter was a squarely built man, about forty years of age, with a face expressive of intense determination, which at the moment was partially hidden by a slouch hat pulled down over the forehead, and a pair of spectacles. He was clad in brown canvas, very much as was Ridge himself; but except for facings of blue on collar and sleeve be wore no distinctive mark of rank. For a few minutes the two talked of the Alamo and all that it represented. Then the stranger asked, abruptly,

"Do you belong to the Rough Riders?"

"No," replied Ridge, "but I hope to. I am going to make application to join them to-morrow, or rather I believe a friend is making it for me this evening. Are you one of them, sir?"

"Yes, though I have not yet joined. In fact, I have only just reached San Antonio."

"So have I," said Ridge. "I came in on the Eastern train less than an hour ago."

"Strange that I did not see you," remarked the other. "Were you in the Pullman?"

"No, I was in a private car."

"I noticed that there was one, though I did not know to whom it belonged. Is it yours?"

"Oh no!" laughed Ridge. "I am far too poor to own anything so luxurious. It belongs to my friend, Mr. Roland Van Kyp, of New York."

"Sometimes called Rollo?"

"Yes; do you know him?"

"I have met him. Is he the one who is to use his influence in your behalf?"

"Yes."

"Can you ride a horse?"

"I have ridden," rejoined Ridge, modestly.

"Where?"

"In many places. The last was Japan, where I won the silver hurdles of the Yokohama gymkana."

"Indeed! And your name is--"

"Ridge Norris," replied the young man.

"I have heard the name, and am glad to know you, Mr. Norris. Now I must bid you good-evening. Hope we shall meet again, and trust you may be successful in joining our regiment."

With this the stranger walked rapidly away, leaving Ridge somewhat puzzled by his manner, and wishing he had asked his name.

About eight o'clock the next morning, as Ridge, waited on by the attentive Robert, was sitting down to the daintily appointed breakfast-table of Rollo Van Kyp's car, the young owner himself burst into the room.

"Hello, Norris!" he cried. "Just going to have lunch? Don't care if I join you. Had breakfast hours ago, you know, and a prime one it was. Scouse, slumgullion, hushpuppy, dope without milk, and all sorts of things. I tell you life in camp is fine, and no mistake. Slept in a dog-tent last night with a full-blooded Indian--Choctaw or something of that kind, one of the best fellows I ever met. Couldn't catch on to his name, but it doesn't make any difference, for all the boys call him 'Hully Gee'--'Hully' for short, you know.

"But such fun and such a rum crowd you never saw! Why, there are cowboys, ranchers, prospectors, coppers, ex-sheriffs, sailors, mine-owners, men from every college in the country, tennis champions, football-players, rowing-men, polo-players, planters, African explorers, big-game hunters, ex-revenue-officers, and Indian-fighters, besides any number of others who have led the wildest kinds of life, all chock-full of stories, and ready to fire 'em off at a touch of the trigger. Teddy hasn't come yet, and so I haven't been able to do anything for you; but you must trot right out, all the same, and join our mess. Besides, I want you to pick out a horse for me, something nice and quiet, 'cause I'm not a dead game rider, you know. Same time he must be good to look at, sound, and fit in every respect. I've already bought one this morning, a devilish pretty little mare, on Sile Pine's say-so that she was gentle, but after a slight though very trying experience, I'm afraid a bronco-buster's ideas of gentleness and mine don't exactly agree."

"Why? Did she throw you?" asked Ridge.

"Well, she didn't exactly throw me. I was merely projected about a thousand yards as though from a dynamite-gun, and then the brute tried to chew me up. You see she's a Mexican--what Mark Twain would call a 'genuine Mexican plug'--and doesn't seem to sabe United States; for when I began to reason with her she simply went wild. I left her tearing through the camp like a steam-cyclone, and if we find anything at all to show where it was located, it is more than I hope for. But there's a new lot of prime-looking cattle just arrived, and they are going like hot cakes; so come along quick and help me get something rideable."

Half an hour later Ridge found himself in the first army camp he had ever visited, amid a body of men the most heterogeneous but typically American ever gathered together. Millionaire dudes and clubmen from the great Eastern cities fraternized with the wildest representatives of far Western life. Men of every calling and social position, all wearing blue flannel shirts and slouch hats, were here mingled on terms of perfect equality. They were drilling, shooting, skylarking, playing cards, performing incredible feats on horseback, cooking, eating, singing, yelling, and behaving in every respect like a lot of irrepressible schoolboys out for a holiday. Here a red-headed Irish corporal damned the awkwardness of a young Boston swell, fresh from Harvard, who had been detailed as cook in a company kitchen; while, close at hand, a New-Yorker of the bluest blood was washing dishes with the deftness gained from long experience on a New Mexican sheep-ranch.

As Ridge and Rollo passed through one of the canvas-bordered streets of this unique camp, the former suddenly leaped aside with an exclamation of alarm. An unknown beast, fortunately chained, had made a spring at him, with sharp claws barely missing his leg.

"You mustn't mind a little thing like that," laughed Rollo, with the air of one to whom such incidents were of every-day occurrence. "It's only 'Josephine,' a young mountain lion from Arizona, and our regimental mascot. She's very playful."

"So it seems," replied Ridge, "and I suppose I shall learn to like her if I join the regiment; but the introduction was a little startling."

A short distance beyond the camp was gathered a confused group of officers, troopers, men in citizen's dress, some of whom were swart-faced Mexicans, and horses. To this Rollo led the way; and, as the new-comers drew near they saw that for a moment all eyes were directed towards a man engaged in a fierce struggle with a horse. The animal was a beautiful chestnut mare with slender limbs, glossy coat, and superb form. Good as she was to look upon, she was just then exhibiting the spirit of a wild-cat or anything else that is most savage and untamable, and was attempting, with desperate struggles, to throw and kill the man who rode her. He was our recent acquaintance, Silas Pine, bronco-buster from the Bad Lands, who, with clinched teeth and rigid features, was in full practice of his chosen profession.

All at once, no one could tell how, but with a furious effort the mare shook off her hated burden, and, with a snort of triumph, dashed madly away. The man was flung heavily to the ground, where he lay motionless.

"That's my horse," remarked Rollo, quietly, "and Sile undertook to either break or kill her. Nice, gentle beast, isn't she? Hello, you're in luck, for there's Roosevelt now. Oh, Teddy! I say, Teddy!"

Two officers on horseback were approaching the scene, and in one of them Ridge recognized his chance acquaintance of the evening before. Towards this individual Van Kyp was running.

All at once the second officer, who proved to be Colonel Leonard Wood of the regular army, now commanding the Riders, turned to a sergeant who stood near by, and said, sharply:

"Arrest that man and take him to the guard-house. We have had enough of this 'Teddy' business, and I want it distinctly understood that hereafter Lieutenant-Colonel Roosevelt is to receive the title of his rank from every man in this command."

In another moment Rollo Van Kyp had been seized by the brawny sergeant, lately a mounted policeman of New York city, and was being marched protestingly away, leaving Ridge bewildered, friendless, and uncertain what to do.

While our hero stood irresolute, he saw Silas Pine gain a sitting posture, and gaze about him with the air of one who is dazed.

"Are you badly hurt?" inquired Ridge, as he reached the man's side.

"I don't know," replied Silas, moving his limbs cautiously, and feeling of various portions of his body to ascertain if any bones were broken. "Reckon not. But will you kindly tell me what happened?"

"You were breaking in Mr. Van Kyp's horse, and got thrown," replied Ridge, as gravely as possible, but with an irrepressible smile lurking in the corners of his mouth.

The bronco-buster, noting this, became instantly filled with wrath.

"Got thrown, did I? And you think it a thing to laugh at, do you? Well, you wouldn't if you'd been in my place. I claim to know something about hosses, and I tell you that's not one at all. She's a 'hoss devil,' that's what she is, for all she looks quiet as a sheep. But I'll kill her yet or die trying to tame her; for such a brute's not fit to live."

"Won't you let me try my hand at it first?" asked Ridge.

"You? you?" exclaimed the man in contemptuous amazement. "Yes, I will, for if you are fool enough to tackle her, you are only fit to be killed, and might as well die now as later. Oh yes, young feller, you can try it; only leave us a lock of your hair to remember you by, and we'll give you a first-class funeral."

By this time two Mexican riders, who had started in pursuit of the runaway animal, had cornered it in an angle of the high fence surrounding the camp-grounds, flung their ropes over its head, and were dragging it back, choking and gasping for breath, to the scene of its recent triumph.

"Hold on!" cried Ridge in Spanish, running towards them as he spoke, and shouting commands in their own language.

Slipping the cruel ropes from the neck of the quivering mare, that stared at him with wild eyes, Ridge petted and soothed her, at the same time talking gently in Spanish, a tongue that she showed signs of understanding by pricking forward her shapely ears. After a little Ridge led the animal to a watering-trough, where she drank greedily, and then into camp, where he begged a handful of sugar from one of the cooks.

Some ten minutes later, without having yet attempted to gain the saddle, he led the mare back to the place from which they had started, all the while talking to her and stroking her glossy neck.

"Why don't you ride?" growled Silas Pine, who still remained on the scene of his recent discomfiture, and had watched Ridge's movements curiously. "Any fool can lead a hoss to water and back again."

For answer Ridge gathered up the bridle reins, and placing his hands on pommel and cantle, sprang lightly into the saddle.

The mare laid her ears flat back and began to tremble with rage, but her rider, bending low over the proud neck, talked to her as though she were a human being, and in another moment they were off like the wind. Twice they circled the entire grounds at a speed as yet unequalled in the camp, and then drew up sharply where Silas Pine still stood awaiting them.

"Mr. Norris," said that individual, stepping forward, "I owe you an apology, and must say I never saw a finer--"

Just here the mare snapped viciously at the bronco-buster, from whose spurs her flanks were still bleeding, and leaped sideways with so sudden a movement that any but a most practiced rider would have been flung to the ground. Without appearing in the least disconcerted by this performance, Ridge began to reply to Silas Pine, but was interrupted by the approach of the two mounted officers, who had watched the recent lesson in bronco-breaking with deep interest.

"Can you do that with any horse?" inquired Lieutenant-Colonel Roosevelt, abruptly.

"I believe I can, sir," replied Ridge, lifting his hand in salute.

"I heard you talking in Spanish. Do you speak it fluently?"

"As well as I do English, sir."

"I believe you wish to enlist in this regiment?"

"I do, sir."

"You are a friend of Private Van Kyp?"

"Yes, sir."

"The one in whose behalf he was about to make application."

Ridge again answered in the affirmative.

"Colonel, I believe we want this young man."

"I believe we do," replied Colonel Wood. Then, to Ridge, he added: "If you can pass a satisfactory physical examination, I know of no reason why you should not be permitted to join this command. I want you to understand, though, that every man admitted to it is chosen solely for personal merit, and not through friendship or any influence, political or otherwise, that he may possess. Now you may take that horse to the picket-line, see that it is properly cared for, and report at my quarters in half an hour."

Without uttering a word in reply, but again saluting, Ridge rode away happier than he had ever been in his life, and prouder even than when he had won the silver hurdles at Yokohama.

An hour later he had successfully passed his physical examination, and was waiting, with a dozen other recruits, to be sworn into the military service of the United States. To these men came Lieutenant-Colonel Roosevelt, who had just resigned the Assistant-Secretaryship of the Navy in order to join the front rank of those who were to fight his country's battles. To them he said: "Gentlemen, you have reached the last point. If any one of you does not mean business, let him say so now. In a few minutes more it will be too late to back out. Once in, you must see the thing through, performing without flinching whatever duty is assigned to you, regardless of its difficulty or danger. If it be garrison duty, you must attend to it; if meeting the fever, you must be willing; if it is the hardest kind of fighting, you must be anxious for it. You must know how to ride, how to shoot, and how to live in the open, lacking all the luxuries and often the necessities of life. No matter what comes, you must not squeal. Remember, above everything, that absolute obedience to every command is your first lesson. Now think it over, and if any man wishes to withdraw, he will be gladly excused, for hundreds stand ready to take his place."

Did any of those young men accept this chance to escape the dangers and privations, the hardships and sufferings, awaiting them? Not one, but all joined in an eager rivalry to first take the oath of allegiance and obedience, and sign the regimental roll.

As it happened, this honor fell to Ridge Norris, and a few minutes later he passed out of the building an enlisted soldier of the United States, a private in its first regiment of volunteer cavalry, and ordered to report to the first sergeant of Troop "K"--Rollo Van Kyp's troop, he remembered with pleasure. "Poor old boy! how I wish I could see him and tell him of my good luck!" he reflected. "Wonder how long he will be kept in that beastly guard-house?"

At the moment our young trooper was passing headquarters, and even as this thought came into his mind, he was bidden by Colonel Wood to deliver a written order to the corporal of the guard. "It is for the release from arrest of your friend Van Kyp," explained the colonel, kindly, "and you may tell him that it was obtained through the intercession of Lieutenant-Colonel Roosevelt."

With a light heart Ridge hastened to perform this first act of his military service; and not long afterwards he and Rollo were happily engaged, under the supervision of Sergeant Higgins, in erecting the little dog-tent that they were to occupy in company, and settling their scanty belongings within its narrow limits. When this was finally accomplished to their satisfaction, they went to the picket-line to visit the pretty and high-spirited mare that had been the immediate cause of Ridge's good fortune.

"Isn't she a beauty?" he exclaimed, walking directly up to the mare, and throwing an arm about her neck, a caress to which the animal submitted with evident pleasure.

"Yes," admitted Rollo, hesitatingly, as he stepped nimbly aside to avoid a snap of white teeth. "I suppose she is, but she seems awfully vicious, and I can't say that she is exactly the style of horse that I most admire. Tell you what I'll do, Norris. I'll give her to you, seeing that you and she seem to hit it off so well. You've won her by rights, anyhow."

Ridge's face flushed. He already loved the mare, and longed to own her, but his pride forbade him to accept so valuable a gift from one who was but little more than a stranger. So he said;

"Oh no! Thanks, awfully, old man, but I couldn't think of taking her in that way. If you don't mind, though, I'll buy the mare of you, gladly paying whatever you gave for her."

"Very good," replied Rollo, who imagined Ridge to be quite well off, and to whom any question of money was of slight consequence. "I paid an even hundred dollars for her with saddle and bridle thrown in, and if you won't accept her as a gift, you may have her for that sum."

"Done," said Ridge, "and here's your money." With this he pulled from his pocket the roll of bills that his father, bidding him not to spend them recklessly, had thrust into his hand on parting, and which until now he had not found occasion to touch.

Although this left our young soldier penniless, he did not for a moment regret the transaction by which he had gained possession of what he considered the very best mount in the whole regiment. He at once named the beautiful mare "Señorita," and upon her he lavished a wealth of affection that seemed to be fully reciprocated. While no one else could do anything with her, in Ridge's hands she gained a knowledge of cavalry tactics as readily as did her young master, and by her quick precision of movement when on drill or parade she was instrumental in raising him first to the grade of corporal, and then to that of sergeant, which was the rank he held three weeks later, on the eve of the Rough Riders' departure for Tampa.

In the mean time the days spent at San Antonio were full of active interest and hard work from morning reveille until the mellow trumpet-notes of taps. At the same time it was work mixed with a vast amount of harmless skylarking, in which both Ridge and Rollo took such active part as to win the liking of every member of their troop.

Each day heard the same anxious inquiry from a thousand tongues: "When shall we go to the front? Is the navy going to fight out this war without the army getting a show?"

"Be patient," counselled the wiser men, "and our chance will come. The powerful Spanish fleet under Admiral Cervera must first be located and rendered harmless, while the army must be licked into effective shape before it is allowed to fight."

They heard of the blockade by the navy of Havana and other Cuban ports, of the apparently fruitless bombardment of San Juan in Porto Rico, and of the great gathering of troops and transports at Tampa. Finally came the welcome news that the dreaded Spanish fleet was safely bottled by Admiral Sampson in the narrow harbor of Santiago.

Then on the 29th of May, only a little more than one month after the declaration of war, came the welcome order to move to Tampa and the front. Instantly the camp presented a scene of wildest bustle and excitement. One hundred railway cars, in six long trains, awaited the Riders. The regiment was drawn up as if for parade.

"Forward, march!" ordered Colonel Wood.

"On to Cuba!" sang the trumpets.

And the "Terrors" yelled themselves hoarse at the prospect of being let loose.

Of course Ridge had written home and informed his family of his whereabouts as soon as he found himself regularly enlisted with the Rough Riders. The news afforded Mr. Norris immense satisfaction, while Spence Cuthbert declared that if Ridge were her brother she should be proud of him.

"If that is said for my benefit," remarked Dulce, "you may rest assured that I am always proud of my brother. I must confess, though, that I should like it better if he were an officer; for, as I have never known any private soldiers, I can't imagine what they are like. It must be very unpleasant, though, to have to associate with them all the time. I wish Ridge had told us more about that Mr. Van Kyp who owns the car. Of course, though, one of his wealth and position must be an officer, a captain at the very least, and perhaps Ridge doesn't see much of him now."

Mrs. Norris was greatly disappointed to find that all her efforts in her son's behalf had been wasted That he should have deliberately chosen to becoming a "common soldier," as she expressed it, instead of accepting the commission offered him, was beyond her comprehension. She mourned and puzzled over this until the arrival of Ridge's next letter, which conveyed the gratifying intelligence that, having been made a corporal, he was now an officer. She did not know what a corporal was, but that Ridge had risen above the ranks of "common soldiers" was sufficient, and from that moment the fond mother began to speak with pride of her son, who was an officer in the cavalry.

At length the quiet household was thrown into a flutter of excitement by the receipt of a telegram, which read:

"Have again been promoted. Regiment ordered to Tampa. Leave to-day. Meet us at Algiers, if possible."

Mr. Norris hurried into the city to consult railway officials concerning the movements of the regiment, and found that the train bearing his son's troop would pass through the city on the morrow.

Early the next morning, therefore, he escorted his wife and the girls across the Mississippi, where, in the forlorn little town of Algiers, they awaited as patiently as might be the coming of their soldier boy. The mother's anxiety to meet her son was almost equalled by her desire to see how handsome he would look in an officer's uniform. Concerning this she had formed a mental picture of epaulettes, gold lace, brass buttons, plumes, and a sword; for had she not seen army officers in Paris?

The two girls discussed as to whether or not Ridge was now travelling in the same luxurious private car that had borne him to San Antonio. Spence thought not, but Dulce believed he would be. "Of course if Ridge was still a private I don't suppose it would be good form for Captain Van Kyp to invite him," she said; "but now that he is an officer, and perhaps even of equal rank, I can't imagine any reason why they should not travel together as they did before."

There was no reason, and the joint proprietors of the little dog-tent, of which, when in marching order, each carried one-half, were travelling together on terms of perfect equality, as was discovered a little later, when the long train, thickly coated with dust and cinders, rumbled heavily into the station. Heads protruded from every window of the crowded coaches, and hundreds of eyes gazed approvingly at the pretty girls who were anxiously looking for a private car, while trying not to blush at the very audible compliments by which they were greeted.

Suddenly they heard the familiar voice. "Mother! Father! Girls!" it called, and turning quickly in that direction, they discovered the object of their search. Sun-browned and dust-begrimed, his face streaked by rivulets of perspiration, wearing a disreputable-looking felt hat and a coarse blue flannel shirt, open at the throat, their boy, beaming with delight, was eagerly beckoning to them. Two other cinder-hued faces were attempting to share the window with him, but with only partial success.

The car doors were guarded, and no one was allowed to pass either in or out until the train was safely on the great boat that was to transfer it across the river. There the turbulent stream of humanity was permitted to burst forth, and in another moment a stalwart young soldier, who seemed to have broadened by inches since she last saw him, had flung his arms about Mrs. Norris's neck. Then he shook hands with his father and kissed both the girls, at which Spence Cuthbert blushed more furiously than ever.

A score of young fellows, all as grimy as Ridge, and all wearing the same uniform, watched this performance curiously, and now the latter began to present them.

"This is First Sergeant Higgins, mother, of our troop, and Mr. Gridley, and Mr. Pine of North Dakota. Dulce, allow me to introduce my tentmate, Mr. Van Kyp."

So he rattled off name after name, until the poor girls were thoroughly bewildered, and could not tell which belonged to whom, especially, as Dulce said, when they all looked exactly alike in those absurd hats, horrid flannel shirts, and ridiculous leggings.

Rollo Van Kyp was the only one of whose name and personality she felt certain, which is probably the reason she allowed that persuasive young trooper to escort her to the forward deck of the boat, where they remained until the river was almost crossed. After a while Ridge and Spence also strolled off together, ostensibly to find Dulce and Rollo, though they did not succeed until the farther shore was nearly reached, when all four came back together.

Rollo Van Kip had lost his hat, while Dulce held tightly in one daintily gloved hand a curious-looking package done up in newspaper. At the same time Spence Cuthbert blushed whenever something in the pocket of her gown gave forth a metallic jingle, and glanced furtively about to see if any one else had heard it.

A few days later Dulce appeared in a new riding-hat, which at once attracted the admiration and envy of all her girl friends. At the same time it was a very common affair, exactly like those worn by Uncle Sam's soldier boys, and on its front was rudely traced in lead pencil the words, "Troop K, Roosevelt's Rough Riders." In fact, it was one of the very hats that Dulce herself had recently designated as "absurd."

About the same time that Miss Norris appeared wearing a trooper's hat her friend Miss Cuthbert decorated the front of her riding-jacket with brass buttons. When Sergeant Norris sharply reprimanded Private Van Kyp for losing his hat, Rollo answered that he considered himself perfectly excusable for so doing, since in a breeze strong enough to blow the buttons off a sergeant's blouse a hat stood no show to remain on its owner's head, whereupon the other abruptly changed the subject.

In the mean time Mrs. Norris, who had recognized among the names of the young men presented to her those of some of the best-known families of the country, was surrounded by a group of Ridge's friends, who, as they all wore the same uniform that he did, she imagined must also be officers. So she delighted their hearts and rose high in their estimation by treating them with great cordiality, and calling them indiscriminately major, captain, or whatever military title happened on the end of her tongue. This she did until her husband appeared on the scene with Lieutenant-Colonel Roosevelt, whom he had known in Washington. The moment the fond mother discovered this gentleman to be her son's superior officer, she neglected every one else to ply him with questions.

"Did he think her boy would make a fine soldier? Was Ridge really an officer? If so, what was his rank, and why did he not wear a more distinctive uniform? Did General Roosevelt believe there would be any fighting, and if there was, would he not order Ridge to remain in the safest places?"

To all of these questions the Lieutenant-Colonel managed to return most satisfactory answers. He thought Ridge was in a fair way to make a most excellent soldier, seeing that he had already gained the rank of sergeant, which was very rapid promotion, considering the short time the young man had been in the service. As to his uniform, he now wore that especially designed for active campaigning, which Mrs. Norris must know was much less showy than one that would be donned for dress parades in time of peace. Yes, he fancied there might be a little fighting, in which case he meditated giving Ridge a place behind Sergeant Borrowe's dynamite gun, where he would be as safe as in any other position on the whole firing line.

Not only was Mrs. Norris greatly comforted by these kindly assurances, but she received further evidence that her boy was indeed an officer entitled to command and be obeyed when the troopers were ordered to re-enter the cars, for she heard him say:

"Come, boys, tumble in lively! Now, Rollo, get a move on."

Certainly an officer to whom even Captain Van Kyp yielded obedience must be of exalted rank.

There was some delay in starting the train, which was taken advantage of by Mr. Norris to disappear, only to return a few minutes later, followed by a porter bearing a great basket of fruit. This was given to Ridge for distribution among his friends. Spence Cuthbert also shyly handed him a box of choice candies, which she had carried all this time; but Dulce, seeing her brother thus well provided, gave her box to Rollo Van Kyp--a proceeding that filled the young millionaire with delight, and caused him to be furiously envied by every other man in the car.

Finally the heavy train began slowly to pull out, its occupants raised a mighty cheer, the trumpeters sounded their liveliest quickstep, and those left behind, waving their handkerchiefs and shouting words of farewell, felt their eyes fill with sudden tears. Until this moment the war had been merely a subject for careless discussion, a thing remote from them and only affecting far-away people. Now it was real and terrible. Their nearest and dearest was concerned in it. They had witnessed the going of those who might never return. From that moment it was their war.

On Thursday, June 2d, with their long, dusty journey ended, the last of the Rough Riders reached Tampa, hot and weary, but in good spirits, and eager to be sent at once to the front. They found 25,000 troops, cavalry, infantry, and artillery, most of them regulars, already encamped in the sandy pine barrens surrounding the little city, and took their place among them.

At Port Tampa, nine miles away, lay the fleet of transports provided to carry them to Cuba. Here they had lain for many days. Here the army had waited for weeks, sweltering in the pitiless heat, suffering the discomforts of a campaign without its stimulant of excitement, impatient of delay, and sick with repeated disappointments. The regulars were ready for service; the volunteers thought they were, but knew better a few weeks later. Time and again orders for embarkation were received, only to be revoked upon rumors of ghostly warships reported off some distant portion of the coast. Spain was playing her old game of mañana at the expense of the Americans, and inducing her powerful enemy to refrain from striking a blow by means of terrifying rumors skilfully circulated through the so-called "yellow journals" of the great American cities, which readily published any falsehood that provided a sensation. At length, however, the last bogie appeared to be laid, and one week after the Riders reached Tampa a rumor of an immediate departure, more definite than any that had preceded it, flashed through the great camp: "Everything is ready, and to-morrow we shall surely embark for Santiago."

Only half the regiment was to go, and no horses could be taken, except a few belonging to officers. The capacity of the transports was limited, and though troops were packed into them like sardines into a can, there was only room for 15,000 men, together with a few horses, a pack-train of mules, four light batteries, and two of siege-guns. So, thousands of soldiers, heartbroken by disappointment, and very many things important to the success of a campaign, were to be left behind.

Two dismounted squadrons of the Rough Riders were chosen to accompany the expedition, which, with the exception of themselves and two regiments of volunteer infantry, was composed of regulars; and, to the great joy of Ridge and his immediate friends, their troop was among those thus selected. But their joy was dimmed by being dismounted, and Ridge almost wept when obliged to part with his beloved mare.

However, as Rollo philosophically remarked, "Everything goes in time of war, or rather most everything does, and what can't go must be left behind."

So five hundred of the horseless riders were piled into a train of empty coal-cars, each man carrying on his person in blanket roll and haversack whatever baggage he was allowed to take, and they were rattled noisily away to Port Tampa, where, after much vexatious delay, they finally boarded the transport Yucatan, and felt that they were fairly off for Cuba.

But not yet. Again came a rumor of strange war-ships hovering off the coast, and with it a frightened but imperative order from Washington to wait. So they waited in the broiling heat, crowded almost to suffocation in narrow spaces--men delicately reared and used to every luxury, men who had never before breathed any but the pure air of mountain or boundless plain--and their only growl was at the delay that kept them from going to where conditions would be even worse. They ate their coarse food whenever and wherever they could get it, drank tepid water from tin cups that were equally available for soup or coffee, and laughed at their discomforts. "But why don't they let us go?" was the constant cry heard on all sides at all hours.

During this most tedious of all their waitings, only one thing of real interest happened. They had heard of the daring exploit of Naval Lieutenant Richmond Pearson Hobson, who, on the night of June 3d, had sunk the big coal-steamer Merrimac in the narrowest part of Santiago Harbor, in the hope of thus preventing the escape of Admiral Cervera's bottled fleet, and they had exulted over this latest example of dauntless American heroism, but none of the details had yet reached them.

On one of their waiting days a swift steam-yacht, now an armed government despatch-boat, dashed into Tampa Bay, and dropped anchor near the Yucatan. Rumor immediately had it that she was from the blockading fleet of Santiago, and every eye was turned upon her with interest. A small boat carried her commanding officer ashore, and while he was gone another brought one of her juniors, Ensign Dick Comly, to visit his only brother, who was a Rough Rider. The Speedy had just come from Santiago, and of course Ensign Comly knew all about Hobson. Would he tell the story of the Merrimac? Certainly he would, and so a few minutes after his arrival the naval man was relating the thrilling tale as follows:

"I don't suppose many of you fellows ever heard of Hobson before this, but every one in the navy knew of him long ago. He is from Alabama, was the youngest man in the Naval Academy class of '89, graduated number 2, was sent abroad to study naval architecture, and, upon returning to this country, was given the rank of Assistant Naval Constructor. At the beginning of this war he was one of the instructors at Annapolis, but immediately applied for active duty, and was assigned to the New York.

"When Victor Blue, of the Suwanee, had proved beyond a doubt by going ashore and counting them that all of Cervera's ships were in Santiago Harbor, Hobson conceived the plan of keeping them there by taking in a ship and sinking it across the channel. Of course it was a perfectly useless thing to do, for Sampson's fleet is powerful enough to lick the stuffing out of the whole Spanish navy, if only it could get the chance. However, the notion took with the Admiral, and Hobson was told to go ahead.

"He selected the collier Merrimac, a big iron steamer 300 feet long, stripped her of all valuable movables, and fastened a lot of torpedoes to her bottom. Each one of these was sufficiently powerful to sink the ship, and all were connected by wires with a button on the bridge. Hobson's plan was to steam into the channel at full speed, regardless of mines or batteries, and anchor his ship across the narrowest part of the channel. There he proposed to blow her up and sink her. What was to become of himself and the half dozen men who were to go with him I don't know, and don't suppose he cared.

"At the same time there was some provision made for escape in case any of them survived the blowing up of their ship. They carried one small dingy along, and an old life-raft was left on board. A steam-launch from the New York was to follow them close in under the batteries, and lie there so long as there was a chance of picking any of them up, or until driven off. Cadets Palmer and Powell, each eager to go on this service, drew lots to see which should command the launch, and luck favored the latter.

"When it was known that six men were wanted to accompany Hobson to almost certain death, four thousand volunteered, and three thousand nine hundred and ninety-four were mightily disappointed when the other six were chosen."

"I should have felt just as they did if I had been left in camp," said Ridge, who was following this story with eager interest.

"Me too," replied Rollo Van Kyp, to whom the remark was addressed.

"The worst of it was," continued the Ensign, "that those fellows didn't get to go, after all, for when they had put in twenty-four hours of hard work on the Merrimac, with no sleep and but little to eat, only kept up by the keenest kind of excitement, it was decided to postpone the attempt until the following night. At the same time the Admiral, fearing the nerve of the men would be shaken by so long a strain, ordered them back to their ships, with thanks for their devotion to the service, and selected six others to take their places. The poor fellows were so broken up by this that some of them cried like babies."

"It was as bad as though we should be ordered to remain behind now," said Ridge.

"Yes," answered Rollo. "But that would be more than I could bear. I'd mutiny and refuse to go ashore. Wouldn't you?"

"I should certainly feel like it," laughed the former. "But orders are orders, and we have sworn to obey them, you know. At the same time there's no cause for worry. We are certain to go if any one does."

"Yes, me and Teddy--" began Rollo, but Ridge silenced him that they might hear the continuation of the Ensign's story.

"At three o'clock on Friday morning, the 3d," resumed Comly, "the Merrimac left the fleet and steamed in towards Santiago entrance. On board, besides Hobson and his six chosen men, was one other, a coxswain of the New York, who had helped prepare the collier for her fate, and at the last moment stowed himself away in her hold for the sake of sharing it.

"With Hobson on the bridge, two men at the wheel, two in the engine-room, two stoking, and one forward ready to cut away the anchor, the doomed ship entered the narrow water-way and passed the outer line of mines in safety. Then the Spaniards discovered her, and from the way they let loose they must have thought the whole American fleet was trying to force the passage. In an instant she was the focus for a perfect cyclone of shot and shell from every gun that could be brought to bear, on both sides of the channel.

"It was like rushing into the very jaws of hell, with mines exploding all about her, solid shot and bursting shells tearing at her vitals, and a cloud of Mauser bullets buzzing like hornets across her deck. How she lived to get where she was wanted is a mystery; but she did, and they sunk her just inside the Estrella battery. At the last they could not steer her, because her rudder was knocked away. So they anchored, waited as cool as cucumbers for the tide to swing her into position, opened all their sea-valves, touched off their torpedoes, and blew her up.

"So far everything had worked to perfection. The seven men, still unhurt, were well aft, where Hobson joined them the moment he had pressed the button; but now their troubles began. The dingy in which they had hoped to escape had been shot to pieces, and they dared not try to get their raft overboard, for the growing light would have revealed their movements, and they would have been a target for every gunner and rifleman within range. So they could only lie flat on deck and wait for something to happen. A little after daybreak the ship sank so low and with such a list that the raft slipped into the water and floated of its own accord. On this all of them, including two had been wounded by flying splinters, rolled overboard after it, caught hold of the clumsy old float, and tried to swim it out to where Powell could pick them up. They had only gained a few yards when a steam-launch coming from the harbor bore down on them. Some marines in the bow were about to open fire, when Hobson sang out, 'Is there any officer on board that launch entitled to receive the surrender of prisoners of war?'

"'Yes, señor, there is,' answered a voice, which also ordered the marines not to fire, and I'll be blowed if Admiral Cervera himself didn't stick his head out from under the awning. The old fellow was as nice as pie to Hobson and his men, told them they had done a fine thing, took them back to his ship, fed them, fitted them out with dry clothing, and then sent Captain Oviedo, his chief of staff, out to the New York, under a flag of truce, to report that the Merrimac's crew, though prisoners, were alive and well. He also offered to carry back any message or supplies the American Admiral might choose to send them. Didn't every soul in that fleet yell when the signal of Hobson's safety was made? Well, I should rather say we did. I only hope old Cervera will fall into our hands some day, so that we can show him how we appreciate his decency."

"Three cheers for the Spanish Admiral right now!" shouted Ridge, and the yell that instantly rose from the deck of the Yucatan in reply was heard on shore for a mile inland.

The noise had barely subsided when a voice called for Sergeant Norris.

"Here I am. Who wants me?" replied Ridge, inquiringly.

"Take your belongings ashore, sir, and report back at camp immediately," was the startling response, delivered in the form of an order by Major Herman Dodley, who was now on the staff of the commanding general. "I have a boat in waiting. If you are ready within two minutes I will set you ashore. Otherwise you will suffer the consequences of your own delay," added the Major, who, while on duty at Port Tampa, had received by telegraph the orders he was now carrying out.

Having ascertained from the captain of his troop that the order brought by Major Dodley was one that must be obeyed, Ridge went below with a very heavy heart to collect his scanty possessions. As he did so his thoughts were full of bitterness. Why should any one be sent back to that hateful camp, and for what reason had he been singled out from all his fellows? It looked as though he were being disgraced, or at least chosen for some duty that would keep him from going to Cuba, which would be almost as bad. At the same time he could not imagine what he had done to incur the displeasure of his superiors. It was all a mystery, and a decidedly unpleasant one. That the order should come through Dodley, too, whom he particularly disliked, was adding insult to injury.

"I'd rather swim ashore than go with that man!" he exclaimed to Rollo Van Kyp, who, full of sympathy, and genuinely distressed at the prospect of their separation, had gone below with him. Ridge had told his chum all about Dodley, whom they had discovered lounging on a breezy veranda of the great Tampa Bay hotel a few days before, so that now the latter fully comprehended his feelings.

"It's a beastly shame!" cried Rollo; "or rather it's two beastly shames, and if you say so, old man, we'll just quietly chuck that Major fellow overboard, so that you can have his boat all to yourself. Then, instead of going ashore, you head down the bay for some place where you can hide until we come along and pick you up."