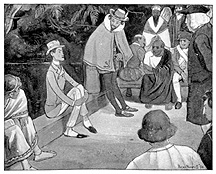

“‘DR. JOHNSON’S POINT IS WELL TAKEN’”

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Pursuit of the House-Boat

Being Some Further Account of the Divers Doings of the Associated Shades, under the Leadership of Sherlock Holmes, Esq.

Author: John Kendrick Bangs

Release Date: July 13, 2005 [eBook #16097]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PURSUIT OF THE HOUSE-BOAT***

Being Some Further Account of the Divers Doings of the Associated Shades, under the Leadership of Sherlock Holmes, Esq.

WITH THE AUTHOR’S SINCEREST REGARDS AND THANKS FOR THE UNTIMELY DEMISE OF HIS GREAT DETECTIVE WHICH MADE THESE THINGS POSSIBLE

The House-boat of the Associated Shades, formerly located upon the River Styx, as the reader may possibly remember, had been torn from its moorings and navigated out into unknown seas by that vengeful pirate Captain Kidd, aided and abetted by some of the most ruffianly inhabitants of Hades. Like a thief in the night had they come, and for no better reason than that the Captain had been unanimously voted a shade too shady to associate with self-respecting spirits had they made off with the happy floating club-house of their betters; and worst of all, with them, by force of circumstances over which they had no control, had sailed also the fair Queen Elizabeth, the spirited Xanthippe, and every other strong-minded and beautiful woman of Erebean society, whereby the men thereof were rendered desolate.

“I can’t stand it!” cried Raleigh, desperately, as with his accustomed grace he presided over a special meeting of the club, called on the bank of the inky Stygian stream, at the point where the missing boat had been moored. “Think of it, gentlemen, Elizabeth of England, Calpurnia of Rome, Ophelia of Denmark, and every precious jewel in our social diadem gone, vanished completely; and with whom? Kidd, of all men in the universe! Kidd, the pirate, the ruffian—”

“Don’t take on so, my dear Sir Walter,” said Socrates, cheerfully. “What’s the use of going into hysterics? You are not a woman, and should eschew that luxury. Xanthippe is with them, and I’ll warrant you that when that cherished spouse of mine has recovered from the effects of the sea, say the third day out, Kidd and his crew will be walking the plank, and voluntarily at that.”

“But the House-boat itself,” murmured Noah, sadly. “That was my delight. It reminded me in some respects of the Ark.”

“The law of compensation enters in there, my dear Commodore,” retorted Socrates. “For me, with Xanthippe abroad I do not need a club to go to; I can stay at home and take my hemlock in peace and straight. Xanthippe always compelled me to dilute it at the rate of one quart of water to the finger.”

“Well, we didn’t all marry Xanthippe,” put in Cæsar, firmly, “therefore we are not all satisfied with the situation. I, for one, quite agree with Sir Walter that something must be done, and quickly. Are we to sit here and do nothing, allowing that fiend to kidnap our wives with impunity?”

“Not at all,” interposed Bonaparte. “The time for action has arrived. All things considered he is welcome to Marie Louise, but the idea of Josephine going off on a cruise of that kind breaks my heart.”

“No question about it,” observed Dr. Johnson. “We’ve got to do something if it is only for the sake of appearances. The question really is, what shall be done first?”

“I am in favor of taking a drink as the first step, and considering the matter of further action afterwards,” suggested Shakespeare, and it was this suggestion that made the members unanimous upon the necessity for immediate action, for when the assembled spirits called for their various favorite beverages it was found that there were none to be had, it being Sunday, and all the establishments wherein liquid refreshments were licensed to be sold being closed—for at the time of writing the local government of Hades was in the hands of the reform party.

“What!” cried Socrates. “Nothing but Styx water and vitriol, Sundays? Then the House-boat must be recovered whether Xanthippe comes with it or not. Sir Walter, I am for immediate action, after all. This ruffian should be captured at once and made an example of.”

“Excuse me, Socrates,” put in Lindley Murray, “but, ah—pray speak in Greek hereafter, will you, please? When you attempt English you have a beastly way of working up to climatic prepositions which are offensive to the ear of a purist.”

“This is no time to discuss style, Murray,” interposed Sir Walter. “Socrates may speak and spell like Chaucer if he pleases; he may even part his infinitives in the middle, for all I care. We have affairs of greater moment in hand.”

“We must ransack the earth,” cried Socrates, “until we find that boat. I’m dry as a fish.”

“There he goes again!” growled Murray. “Dry as a fish! What fish I’d like to know is dry?”

“Red herrings,” retorted Socrates; and there was a great laugh at the expense of the purist, in which even Hamlet, who had grown more and more melancholy and morbid since the abduction of Ophelia, joined.

“Then it is settled,” said Raleigh; “something must be done. And now the point is, what?”

“Relief expeditions have a way of finding things,” suggested Dr. Livingstone. “Or rather of being found by the things they go out to relieve. I propose that we send out a number of them. I will take Africa; Bonaparte can lead an expedition into Europe; General Washington may have North America; and—”

“I beg pardon,” put in Dr. Johnson, “but have you any idea, Dr. Livingstone, that Captain Kidd has put wheels on this House-boat of ours and is having it dragged across the Sahara by mules or camels?”

“No such absurd idea ever entered my head,” retorted the Doctor.

“Do you then believe that he has put runners on it, and is engaged in the pleasurable pastime of taking the ladies tobogganing down the Alps?” persisted the philosopher.

“Not at all. Why do you ask?” queried the African explorer, irritably.

“Because I wish to know,” said Johnson. “That is always my motive in asking questions. You propose to go looking for a house-boat in Central Africa; you suggest that Bonaparte lead an expedition in search of it through Europe—all of which strikes me as nonsense. This search is the work of sea-dogs, not of landlubbers. You might as well ask Confucius to look for it in the heart of China. What earthly use there is in ransacking the earth I fail to see. What we need is a naval expedition to scour the sea, unless it is pretty well understood in advance that we believe Kidd has hauled the boat out of the water, and is now using it for a roller-skating rink or a bicycle academy in Ohio, or for some other purpose for which neither he nor it was designed.”

“Dr. Johnson’s point is well taken,” said a stranger who had been sitting upon the string-piece of the pier, quietly, but with very evident interest, listening to the discussion. He was a tall and excessively slender shade, “like a spirt of steam out of a teapot,” as Johnson put it afterwards, so slight he seemed. “I have not the honor of being a member of this association,” the stranger continued, “but, like all well-ordered shades, I aspire to the distinction, and I hold myself and my talents at the disposal of this club. I fancy it will not take us long to establish our initial point, which is that the gross person who has so foully appropriated your property to his own base uses does not contemplate removing it from its keel and placing it somewhere inland. All the evidence in hand points to a radically different conclusion, which is my sole reason for doubting the value of that conclusion. Captain Kidd is a seafarer by instinct, not a landsman. The House-boat is not a house, but a boat; therefore the place to look for it is not, as Dr. Johnson so well says, in the Sahara Desert, or on the Alps, or in the State of Ohio, but upon the high sea, or upon the waterfront of some one of the world’s great cities.”

“And what, then, would be your plan?” asked Sir Walter, impressed by the stranger’s manner as well as by the very manifest reason in all that he had said.

“The chartering of a suitable vessel, fully armed and equipped for the purpose of pursuit. Ascertain whither the House-boat has sailed, for what port, and start at once. Have you a model of the House-boat within reach?” returned the stranger.

“I think not; we have the architect’s plans, however,” said the chairman.

“We had, Mr. Chairman,” said Demosthenes, who was secretary of the House Committee, rising, “but they are gone with the House-boat itself. They were kept in the safe in the hold.”

A look of annoyance came into the face of the stranger.

“That’s too bad,” he said. “It was a most important part of my plan that we should know about how fast the House-boat was.”

“Humph!” ejaculated Socrates, with ill-concealed sarcasm. “If you’ll take Xanthippe’s word for it, the House-boat was the fastest yacht afloat.”

“I refer to the matter of speed in sailing,” returned the stranger, quietly. “The question of its ethical speed has nothing to do with it.”

“The designer of the craft is here,” said Sir Walter, fixing his eyes upon Sir Christopher Wren. “It is possible that he may be of assistance in settling that point.”

“What has all this got to do with the question, anyhow, Mr. Chairman?” asked Solomon, rising impatiently and addressing Sir Walter. “We aren’t preparing for a yacht-race that I know of. Nobody’s after a cup, or a championship of any kind. What we do want is to get our wives back. The Captain hasn’t taken more than half of mine along with him, but I am interested none the less. The Queen of Sheba is on board, and I am somewhat interested in her fate. So I ask you what earthly or unearthly use there is in discussing this question of speed in the House-boat. It strikes me as a woful waste of time, and rather unprecedented too, that we should suspend all rules and listen to the talk of an entire stranger.”

“I do not venture to doubt the wisdom of Solomon,” said Johnson, dryly, “but I must say that the gentleman’s remarks rather interest me.”

“Of course they do,” ejaculated Solomon. “He agreed with you. That ought to make him interesting to everybody. Freaks usually are.”

“That is not the reason at all,” retorted Dr. Johnson. “Cold water agrees with me, but it doesn’t interest me. What I do think, however, is that our unknown friend seems to have a grasp on the situation by which we are confronted, and he’s going at the matter in hand in a very comprehensive fashion. I move, therefore, that Solomon be laid on the table, and that the privileges of the—ah—of the wharf be extended indefinitely to our friend on the string-piece.”

The motion, having been seconded, was duly carried, and the stranger resumed.

“I will explain for the benefit of his Majesty King Solomon, whose wisdom I have always admired, and whose endurance as the husband of three hundred wives has filled me with wonder,” he said, “that before starting in pursuit of the stolen vessel we must select a craft of some sort for the purpose, and that in selecting the pursuer it is quite essential that we should choose a vessel of greater speed than the one we desire to overtake. It would hardly be proper, I think, if the House-boat can sail four knots an hour, to attempt to overhaul her with a launch, or other nautical craft, with a maximum speed of two knots an hour.”

“Hear! hear!” ejaculated Cæsar.

“That is my reason, your Majesty, for inquiring as to the speed of your late club-house,” said the stranger, bowing courteously to Solomon. “Now if Sir Christopher Wren can give me her measurements, we can very soon determine at about what rate she is leaving us behind under favorable circumstances.”

“’Tisn’t necessary for Sir Christopher to do anything of the sort,” said Noah, rising and manifesting somewhat more heat than the occasion seemed to require. “As long as we are discussing the question I will take the liberty of stating what I have never mentioned before, that the designer of the House-boat merely appropriated the lines of the Ark. Shem, Ham, and Japhet will bear testimony to the truth of that statement.”

“There can be no quarrel on that score, Mr. Chairman,” assented Sir Christopher, with cutting frigidity. “I am perfectly willing to admit that practically the two vessels were built on the same lines, but with modifications which would enable my boat to sail twenty miles to windward and back in six days less time than it would have taken the Ark to cover the same distance, and it could have taken all the wash of the excursion steamers into the bargain.”

“Bosh!” ejaculated Noah, angrily. “Strip your old tub down to a flying balloon-jib and a marline-spike, and ballast the Ark with elephants until every inch of her reeked with ivory and peanuts, and she’d outfoot you on every leg, in a cyclone or a zephyr. Give me the Ark and a breeze, and your House-boat wouldn’t be within hailing distance of her five minutes after the start if she had 40,000 square yards of canvas spread before a gale.”

“This discussion is waxing very unprofitable,” observed Confucius. “If these gentlemen cannot be made to confine themselves to the subject that is agitating this body, I move we call in the authorities and have them confined in the bottomless pit.”

“I did not precipitate the quarrel,” said Noah. “I was merely trying to assist our friend on the string-piece. I was going to say that as the Ark was probably a hundred times faster than Sir Christopher Wren’s—tub, which he himself says can take care of all the wash of the excursion boats, thereby becoming on his own admission a wash-tub—”

“Order! order!” cried Sir Christopher.

“I was going to say that this wash-tub could be overhauled by a launch or any other craft with a speed of thirty knots a month,” continued Noah, ignoring the interruption.

“Took him forty days to get to Mount Ararat!” sneered Sir Christopher.

“Well, your boat would have got there two weeks sooner, I’ll admit,” retorted Noah, “if she’d sprung a leak at the right time.”

“Granting the truth of Noah’s statement,” said Sir Walter, motioning to the angry architect to be quiet—“not that we take any side in the issue between the two gentlemen, but merely for the sake of argument—I wish to ask the stranger who has been good enough to interest himself in our trouble what he proposes to do—how can you establish your course in case a boat were provided?”

“Also vot vill be dher gost, if any?” put in Shylock.

A murmur of disapprobation greeted this remark.

“The cost need not trouble you, sir,” said Sir Walter, indignantly, addressing the stranger; “you will have carte blanche.”

“Den ve are ruint!” cried Shylock, displaying his palms, and showing by that act a select assortment of diamond rings.

“Oh,” laughed the stranger, “that is a simple matter. Captain Kidd has gone to London.”

“To London!” cried several members at once. “How do you know that?”

“By this,” said the stranger, holding up the tiny stub end of a cigar.

“Tut-tut!” ejaculated Solomon. “What child’s play this is!”

“No, your Majesty,” observed the stranger, “it is not child’s play; it is fact. That cigar end was thrown aside here on the wharf by Captain Kidd just before he stepped on board the House-boat.”

“How do you know that?” demanded Raleigh. “And granting the truth of the assertion, what does it prove?”

“I will tell you,” said the stranger. And he at once proceeded as follows.

“I have made a hobby of the study of cigar ends,” said the stranger, as the Associated Shades settled back to hear his account of himself. “From my earliest youth, when I used surreptitiously to remove the unsmoked ends of my father’s cigars and break them up, and, in hiding, smoke them in an old clay pipe which I had presented to me by an ancient sea-captain of my acquaintance, I have been interested in tobacco in all forms, even including these self-same despised unsmoked ends; for they convey to my mind messages, sentiments, farces, comedies, and tragedies which to your minds would never become manifest through their agency.”

The company drew closer together and formed themselves in a more compact mass about the speaker. It was evident that they were beginning to feel an unusual interest in this extraordinary person, who had come among them unheralded and unknown. Even Shylock stopped calculating percentages for an instant to listen.

“Do you mean to tell us,” demanded Shakespeare, “that the unsmoked stub of a cigar will suggest the story of him who smoked it to your mind?”

“I do,” replied the stranger, with a confident smile. “Take this one, for instance, that I have picked up here upon the wharf; it tells me the whole story of the intentions of Captain Kidd at the moment when, in utter disregard of your rights, he stepped aboard your House-boat, and, in his usual piratical fashion, made off with it into unknown seas.”

“But how do you know he smoked it?” asked Solomon, who deemed it the part of wisdom to be suspicious of the stranger.

“There are two curious indentations in it which prove that. The marks of two teeth, with a hiatus between, which you will see if you look closely,” said the stranger, handing the small bit of tobacco to Sir Walter, “make that point evident beyond peradventure. The Captain lost an eye-tooth in one of his later raids; it was knocked out by a marline-spike which had been hurled at him by one of the crew of the treasure-ship he and his followers had attacked. The adjacent teeth were broken, but not removed. The cigar end bears the marks of those two jagged molars, with the hiatus, which, as I have indicated, is due to the destruction of the eye-tooth between them. It is not likely that there was another man in the pirate’s crew with teeth exactly like the commander’s, therefore I say there can be no doubt that the cigar end was that of the Captain himself.”

“Very interesting indeed,” observed Blackstone, removing his wig and fanning himself with it; “but I must confess, Mr. Chairman, that in any properly constituted law court this evidence would long since have been ruled out as irrelevant and absurd. The idea of two or three hundred dignified spirits like ourselves, gathered together to devise a means for the recovery of our property and the rescue of our wives, yielding the floor to the delivering of a lecture by an entire stranger on ‘Cigar Ends He Has Met,’ strikes me as ridiculous in the extreme. Of what earthly interest is it to us to know that this or that cigar was smoked by Captain Kidd?”

“Merely that it will help us on, your honor, to discover the whereabouts of the said Kidd,” interposed the stranger. “It is by trifles, seeming trifles, that the greatest detective work is done. My friends Le Coq, Hawkshaw, and Old Sleuth will bear me out in this, I think, however much in other respects our methods may have differed. They left no stone unturned in the pursuit of a criminal; no detail, however trifling, uncared for. No more should we in the present instance overlook the minutest bit of evidence, however irrelevant and absurd at first blush it may appear to be. The truth of what I say was very effectually proven in the strange case of the Brokedale tiara, in which I figured somewhat conspicuously, but which I have never made public, because it involves a secret affecting the integrity of one of the noblest families in the British Empire. I really believe that mystery was solved easily and at once because I happened to remember that the number of my watch was 86507B. How trivial a thing, and yet how important it was, as the event transpired, you will realize when I tell you the incident.”

The stranger’s manner was so impressive that there was a unanimous and simultaneous movement upon the part of all present to get up closer, so as the more readily to hear what he said, as a result of which poor old Boswell was pushed overboard, and fell with a loud splash into the Styx. Fortunately, however, one of Charon’s pleasure-boats was close at hand, and in a short while the dripping, sputtering spirit was drawn into it, wrung out, and sent home to dry. The excitement attending this diversion having subsided, Solomon asked:

“What was the incident of the lost tiara?”

“I am about to tell you,” returned the stranger; “and it must be understood that you are told in the strictest confidence, for, as I say, the incident involves a state secret of great magnitude. In life—in the mortal life—gentlemen, I was a detective by profession, and, if I do say it, who perhaps should not, I was one of the most interesting for purely literary purposes that has ever been known. I did not find it necessary to go about saying ‘Ha! ha!’ as M. Le Coq was accustomed to do to advertise his cleverness; neither did I disguise myself as a drum-major and hide under a kitchen-table for the purpose of solving a mystery involving the abduction of a parlor stove, after the manner of the talented Hawkshaw. By mental concentration alone, without fireworks or orchestral accompaniment of any sort whatsoever, did I go about my business, and for that very reason many of my fellow-sleuths were forced to go out of real detective work into that line of the business with which the stage has familiarized the most of us—a line in which nothing but stupidity, luck, and a yellow wig is required of him who pursues it.”

“This man is an impostor,” whispered Le Coq to Hawkshaw.

“I’ve known that all along by the mole on his left wrist,” returned Hawkshaw, contemptuously.

“I suspected it the minute I saw he was not disguised,” returned Le Coq, knowingly. “I have observed that the greatest villains latterly have discarded disguises, as being too easily penetrated, and therefore of no avail, and merely a useless expense.”

“Silence!” cried Confucius, impatiently. “How can the gentleman proceed, with all this conversation going on in the rear?”

Hawkshaw and Le Coq immediately subsided, and the stranger went on.

“It was in this way that I treated the strange case of the lost tiara,” resumed the stranger. “Mental concentration upon seemingly insignificant details alone enabled me to bring about the desired results in that instance. A brief outline of the case is as follows: It was late one evening in the early spring of 1894. The London season was at its height. Dances, fêtes of all kinds, opera, and the theatres were in full blast, when all of a sudden society was paralyzed by a most audacious robbery. A diamond tiara valued at £50,000 sterling had been stolen from the Duchess of Brokedale, and under circumstances which threw society itself and every individual in it under suspicion—even his Royal Highness the Prince himself, for he had danced frequently with the Duchess, and was known to be a great admirer of her tiara. It was at half-past eleven o’clock at night that the news of the robbery first came to my ears. I had been spending the evening alone in my library making notes for a second volume of my memoirs, and, feeling somewhat depressed, I was on the point of going out for my usual midnight walk on Hampstead Heath, when one of my servants, hastily entering, informed me of the robbery. I changed my mind in respect to my midnight walk immediately upon receipt of the news, for I knew that before one o’clock some one would call upon me at my lodgings with reference to this robbery. It could not be otherwise. Any mystery of such magnitude could no more be taken to another bureau than elephants could fly—”

“They used to,” said Adam. “I once had a whole aviary full of winged elephants. They flew from flower to flower, and thrusting their probabilities deep into—”

“Their what?” queried Johnson, with a frown.

“Probabilities—isn’t that the word? Their trunks,” said Adam.

“Probosces, I imagine you mean,” suggested Johnson.

“Yes—that was it. Their probosces,” said Adam. “They were great honey-gatherers, those elephants—far better than the bees, because they could make so much more of it in a given time.”

Munchausen shook his head sadly. “I’m afraid I’m outclassed by these antediluvians,” he said.

“Gentlemen! gentlemen!” cried Sir Walter. “These interruptions are inexcusable!”

“That’s what I think,” said the stranger, with some asperity. “I’m having about as hard a time getting this story out as I would if it were a serial. Of course, if you gentlemen do not wish to hear it, I can stop; but it must be understood that when I do stop I stop finally, once and for all, because the tale has not a sufficiency of dramatic climaxes to warrant its prolongation over the usual magazine period of twelve months.”

“Go on! go on!” cried some.

“Shut up!” cried others—addressing the interrupting members, of course.

“As I was saying,” resumed the stranger, “I felt confident that within an hour, in some way or other, that case would be placed in my hands. It would be mine either positively or negatively—that is to say, either the person robbed would employ me to ferret out the mystery and recover the diamonds, or the robber himself, actuated by motives of self-preservation, would endeavor to direct my energies into other channels until he should have the time to dispose of his ill-gotten booty. A mental discussion of the probabilities inclined me to believe that the latter would be the case. I reasoned in this fashion: The person robbed is of exalted rank. She cannot move rapidly because she is so. Great bodies move slowly. It is probable that it will be a week before, according to the etiquette by which she is hedged about, she can communicate with me. In the first place, she must inform one of her attendants that she has been robbed. He must communicate the news to the functionary in charge of her residence, who will communicate with the Home Secretary, and from him will issue the orders to the police, who, baffled at every step, will finally address themselves to me. ‘I’ll give that side two weeks,’ I said. On the other hand, the robber: will he allow himself to be lulled into a false sense of security by counting on this delay, or will he not, noting my habit of occasionally entering upon detective enterprises of this nature of my own volition, come to me at once and set me to work ferreting out some crime that has never been committed? My feeling was that this would happen, and I pulled out my watch to see if it were not nearly time for him to arrive. The robbery had taken place at a state ball at the Buckingham Palace. ‘H’m!’ I mused. ‘He has had an hour and forty minutes to get here. It is now twelve twenty. He should be here by twelve forty-five. I will wait.’ And hastily swallowing a cocaine tablet to nerve myself up for the meeting, I sat down and began to read my Schopenhauer. Hardly had I perused a page when there came a tap upon my door. I rose with a smile, for I thought I knew what was to happen, opened the door, and there stood, much to my surprise, the husband of the lady whose tiara was missing. It was the Duke of Brokedale himself. It is true he was disguised. His beard was powdered until it looked like snow, and he wore a wig and a pair of green goggles; but I recognized him at once by his lack of manners, which is an unmistakable sign of nobility. As I opened the door, he began:

“‘You are Mr.—’

“‘I am,’ I replied. ‘Come in. You have come to see me about your stolen watch. It is a gold hunting-case watch with a Swiss movement; loses five minutes a day; stem-winder; and the back cover, which does not bear any inscription, has upon it the indentations made by the molars of your son Willie when that interesting youth was cutting his teeth upon it.’”

“Wonderful!” cried Johnson.

“May I ask how you knew all that?” asked Solomon, deeply impressed. “Such penetration strikes me as marvellous.”

“I didn’t know it,” replied the stranger, with a smile. “What I said was intended to be jocular, and to put Brokedale at his ease. The Americans present, with their usual astuteness, would term it bluff. It was. I merely rattled on. I simply did not wish to offend the gentleman by letting him know that I had penetrated his disguise. Imagine my surprise, however, when his eye brightened as I spoke, and he entered my room with such alacrity that half the powder which he thought disguised his beard was shaken off on to the floor. Sitting down in the chair I had just vacated, he quietly remarked:

“‘You are a wonderful man, sir. How did you know that I had lost my watch?’

“For a moment I was nonplussed; more than that, I was completely staggered. I had expected him to say at once that he had not lost his watch, but had come to see me about the tiara; and to have him take my words seriously was entirely unexpected and overwhelmingly surprising. However, in view of his rank, I deemed it well to fall in with his humor. ‘Oh, as for that,’ I replied, ‘that is a part of my business. It is the detective’s place to know everything; and generally, if he reveals the machinery by means of which he reaches his conclusions, he is a fool, since his method is his secret, and his secret his stock in trade. I do not mind telling you, however, that I knew your watch was stolen by your anxious glance at my clock, which showed that you wished to know the time. Now most rich Americans have watches for that purpose, and have no hesitation about showing them. If you’d had a watch, you’d have looked at it, not at my clock.’

“My visitor laughed, and repeated what he had said about my being a wonderful man.

“‘And the dents which my son made cutting his teeth?’ he added.

“‘Invariably go with an American’s watch. Rubber or ivory rings aren’t good enough for American babies to chew on,’ said I. ‘They must have gold watches or nothing.’

“‘And finally, how did you know I was a rich American?’ he asked.

“‘Because no other can afford to stop at hotels like the Savoy in the height of the season,’ I replied, thinking that the jest would end there, and that he would now reveal his identity and speak of the tiara. To my surprise, however, he did nothing of the sort.

“‘You have an almost supernatural gift,’ he said. ‘My name is Bunker. I am stopping at the Savoy. I am an American. I was rich when I arrived here, but I’m not quite so bloated with wealth as I was, now that I have paid my first week’s bill. I have lost my watch; such a watch, too, as you describe, even to the dents. Your only mistake was that the dents were made by my son John, and not Willie; but even there I cannot but wonder at you, for John and Willie are twins, and so much alike that it sometimes baffles even their mother to tell them apart. The watch has no very great value intrinsically, but the associations are such that I want it back, and I will pay £200 for its recovery. I have no clew as to who took it. It was numbered—’

“Here a happy thought struck me. In all my description of the watch I had merely described my own, a very cheap affair which I had won at a raffle. My visitor was deceiving me, though for what purpose I did not on the instant divine. No one would like to suspect him of having purloined his wife’s tiara. Why should I not deceive him, and at the same time get rid of my poor chronometer for a sum that exceeded its value a hundredfold?”

“Good business!” cried Shylock.

The stranger smiled and bowed.

“Excellent,” he said. “I took the words right out of his mouth. ‘It was numbered 86507B!’ I cried, giving, of course, the number of my own watch.

“He gazed at me narrowly for a moment, and then he smiled. ‘You grow more marvellous at every step. That was indeed the number. Are you a demon?’

“‘No,’ I replied. ‘Only something of a mind-reader.’

“Well, to be brief, the bargain was struck. I was to look for a watch that I knew he hadn’t lost, and was to receive £200 if I found it. It seemed to him to be a very good bargain, as, indeed, it was, from his point of view, feeling, as he did, that there never having been any such watch, it could not be recovered, and little suspecting that two could play at his little game of deception, and that under any circumstances I could foist a ten-shilling watch upon him for two hundred pounds. This business concluded, he started to go.

“‘Won’t you have a little Scotch?’ I asked, as he started, feeling, with all that prospective profit in view, I could well afford the expense. ‘It is a stormy night.’

“‘Thanks, I will,’ said he, returning and seating himself by my table—still, to my surprise, keeping his hat on.

“‘Let me take your hat,’ I said, little thinking that my courtesy would reveal the true state of affairs. The mere mention of the word hat brought about a terrible change in my visitor; his knees trembled, his face grew ghastly, and he clutched the brim of his beaver until it cracked. He then nervously removed it, and I noticed a dull red mark running about his forehead, just as there would be on the forehead of a man whose hat fitted too tightly; and that mark, gentlemen, had the undulating outline of nothing more nor less than a tiara, and on the apex of the uppermost extremity was a deep indentation about the size of a shilling, that could have been made only by some adamantine substance! The mystery was solved! The robber of the Duchess of Brokedale stood before me.”

A suppressed murmur of excitement went through the assembled spirits, and even Messrs. Hawkshaw and Le Coq were silent in the presence of such genius.

“My plan of action was immediately formulated. The man was completely at my mercy. He had stolen the tiara, and had it concealed in the lining of his hat. I rose and locked the door. My visitor sank with a groan into my chair.

“‘Why did you do that?’ he stammered, as I turned the key in the lock.

“‘To keep my Scotch whiskey from evaporating,’ I said, dryly. ‘Now, my lord,’ I added, ‘it will pay your Grace to let me have your hat. I know who you are. You are the Duke of Brokedale. The Duchess of Brokedale has lost a valuable tiara of diamonds, and you have not lost your watch. Somebody has stolen the diamonds, and it may be that somewhere there is a Bunker who has lost such a watch as I have described. The queer part of it all is,’ I continued, handing him the decanter, and taking a couple of loaded six-shooters out of my escritoire—‘the queer part of it all is that I have the watch and you have the tiara. We’ll swap the swag. Hand over the bauble, please.’

“‘But—’ he began.

“‘We won’t have any butting, your Grace,’ said I. ‘I’ll give you the watch, and you needn’t mind the £200; and you must give me the tiara, or I’ll accompany you forthwith to the police, and have a search made of your hat. It won’t pay you to defy me. Give it up.’

“He gave up the hat at once, and, as I suspected, there lay the tiara, snugly stowed away behind the head-band.

“‘You are a great fellow.’ said I, as I held the tiara up to the light and watched with pleasure the flashing brilliance of its gems.

“‘I beg you’ll not expose me,’ he moaned. ‘I was driven to it by necessity.’

“‘Not I,’ I replied. ‘As long as you play fair it will be all right. I’m not going to keep this thing. I’m not married, and so have no use for such a trifle; but what I do intend is simply to wait until your wife retains me to find it, and then I’ll find it and get the reward. If you keep perfectly still, I’ll have it found in such a fashion that you’ll never be suspected. If, on the other hand, you say a word about to-night’s events, I’ll hand you over to the police.’

“‘Humph!’ he said. ‘You couldn’t prove a case against me.’

“‘I can prove any case against anybody,’ I retorted. ‘If you don’t believe it, read my book,’ I added, and I handed him a copy of my memoirs.

“‘I’ve read it,’ he answered, ‘and I ought to have known better than to come here. I thought you were only a literary success.’ And with a deep-drawn sigh he took the watch and went out. Ten days later I was retained by the Duchess, and after a pretended search of ten days more I found the tiara, restored it to the noble lady, and received the £5000 reward. The Duke kept perfectly quiet about our little encounter, and afterwards we became stanch friends; for he was a good fellow, and was driven to his desperate deed only by the demands of his creditors, and the following Christmas he sent me the watch I had given him, with the best wishes of the season.

“So, you see, gentlemen, in a moment, by quick wit and a mental concentration of no mean order, combined with strict observance of the pettiest details, I ferreted out what bade fair to become a great diamond mystery; and when I say that this cigar end proves certain things to my mind, it does not become you to doubt the value of my conclusions.”

“Hear! hear!” cried Raleigh, growing tumultuous with enthusiasm.

“Your name? your name?” came from all parts of the wharf.

The stranger, putting his hand into the folds of his coat, drew forth a bundle of business cards, which he tossed, as the prestidigitator tosses playing-cards, out among the audience, and on each of them was found printed the words:

SHERLOCK HOLMES,

DETECTIVE.

Ferreting Done Here.

Plots for Sale.

“I think he made a mistake in not taking the £200 for the watch. Such carelessness destroys my confidence in him,” said Shylock, who was the first to recover from the surprise of the revelation.

“Well, Mr. Holmes,” said Sir Walter Raleigh, after three rousing cheers, led by Hamlet, had been given with a will by the assembled spirits, “after this demonstration in your honor I think it is hardly necessary for me to assure you of our hearty co-operation in anything you may venture to suggest. There is still manifest, however, some desire on the part of the ever-wise King Solomon and my friend Confucius to know how you deduce that Kidd has sailed for London, from the cigar end which you hold in your hand.”

“I can easily satisfy their curiosity,” said Sherlock Holmes, genially. “I believe I have already proven that it is the end of Kidd’s cigar. The marks of the teeth have shown that. Now observe how closely it is smoked—there is barely enough of it left for one to insert between his teeth. Now Captain Kidd would hardly have risked the edges of his mustache and the comfort of his lips by smoking a cigar down to the very light if he had had another; nor would he under any circumstances have smoked it that far unless he were passionately addicted to this particular brand of the weed. Therefore I say to you, first, this was his cigar; second, it was the last one he had; third, he is a confirmed smoker. The result, he has gone to the one place in the world where these Connecticut hand-rolled Havana cigars—for I recognize this as one of them—have a real popularity, and are therefore more certainly obtainable, and that is at London. You cannot get so vile a cigar as that outside of a London hotel. If I could have seen a quarter-inch more of it, I should have been able definitely to locate the hotel itself. The wrappers unroll to a degree that varies perceptibly as between the different hotels. The Metropole cigar can be smoked a quarter through before its wrapper gives way; the Grand wrapper goes as soon as you light the cigar; whereas the Savoy, fronting on the Thames, is surrounded by a moister atmosphere than the others, and, as a consequence, the wrapper will hold really until most people are willing to throw the whole thing away.”

“It is really a wonderful art!” said Solomon.

“The making of a Connecticut Havana cigar?” laughed Holmes. “Not at all. Give me a head of lettuce and a straw, and I’ll make you a box.”

“I referred to your art—that of detection,” said Solomon. “Your logic is perfect; step by step we have been led to the irresistible conclusion that Kidd has made for London, and can be found at one of these hotels.”

“And only until next Tuesday, when he will take a house in the neighborhood of Scotland Yard,” put in Holmes, quickly, observing a sneer on Hawkshaw’s lips, and hastening to overwhelm him by further evidence of his ingenuity. “When he gets his bill he will open his piratical eyes so wide that he will be seized with jealousy to think of how much more refined his profession has become since he left it, and out of mere pique he will leave the hotel, and, to show himself still cleverer than his modern prototypes, he will leave his account unpaid, with the result that the affair will be put in the hands of the police, under which circumstances a house in the immediate vicinity of the famous police headquarters will be the safest hiding-place he can find, as was instanced by the remarkable case of the famous Penstock bond robbery. A certain church-warden named Hinkley, having been appointed cashier thereof, robbed the Penstock Imperial Bank of £1,000,000 in bonds, and, fleeing to London, actually joined the detective force at Scotland Yard, and was detailed to find himself, which of course he never did, nor would he ever have been found had he not crossed my path.”

Hawkshaw gazed mournfully off into space, and Le Coq muttered profane words under his breath.

“We’re not in the same class with this fellow, Hawkshaw,” said Le Coq. “You could tap your forehead knowingly eight hours a day through all eternity with a sledge-hammer without loosening an idea like that.”

“Nevertheless I’ll confound him yet,” growled the jealous detective. “I shall myself go to London, and, disguised as Captain Kidd, will lead this visionary on until he comes there to arrest me, and when these club members discover that it is Hawkshaw and not Kidd he has run to earth, we’ll have a great laugh on Sherlock Holmes.”

“I am anxious to hear how you solved the bond-robbery mystery,” said Socrates, wrapping his toga closely about him and settling back against one of the spiles of the wharf.

“So are we all,” said Sir Walter. “But meantime the House-boat is getting farther away.”

“Not unless she’s sailing backwards,” sneered Noah, who was still nursing his resentment against Sir Christopher Wren for his reflections upon the speed of the Ark.

“What’s the hurry?” asked Socrates. “I believe in making haste slowly; and on the admission of our two eminent naval architects, Sir Christopher and Noah, neither of their vessels can travel more than a mile a week, and if we charter the Flying Dutchman to go in pursuit of her we can catch her before she gets out of the Styx into the Atlantic.”

“Jonah might lend us his whale, if the beast is in commission,” suggested Munchausen, dryly. “I for one would rather take a state-room in Jonah’s whale than go aboard the Flying Dutchman again. I made one trip on the Dutchman, and she’s worse than a dory for comfort; furthermore, I don’t see what good it would do us to charter a boat that can’t land oftener than once in seven years, and spends most of her time trying to double the Cape of Good Hope.”

“My whale is in commission,” said Jonah, with dignity. “But Baron Munchausen need not consider the question of taking a state-room aboard of her. She doesn’t carry second-class passengers. And if I took any stock in the idea of a trip on the Flying Dutchman amounting to a seven years’ exile, I would cheerfully pay the Baron’s expenses for a round trip.”

“We are losing time, gentlemen,” suggested Sherlock Holmes. “This is a moment, I think, when you should lay aside personal differences and personal preferences for immediate action. I have examined the wake of the House-boat, and I judge from the condition of what, for want of a better term, I may call the suds, when she left us the House-boat was making ten knots a day. Almost any craft we can find suitably manned ought to be able to do better than that; and if you could summon Charon and ascertain what boats he has at hand, it would be for the good of all concerned.”

“That’s a good plan,” said Johnson. “Boswell, see if you can find Charon.”

“I am here already, sir,” returned the ferryman, rising. “Most of my boats have gone into winter quarters, your Honor. The Mayflower went into dry dock last week to be calked up; the Pinta and the Santa Maria are slow and cranky; the Monitor and the Merrimac I haven’t really had time to patch up; and the Valkyrie is two months overdue. I cannot make up my mind whether she is lost or kept back by excursion steamers. Hence I really don’t know what I can lend you. Any of these boats I have named you could have had for nothing; but my others are actively employed, and I couldn’t let them go without a serious interference with my business.”

The old man blinked sorrowfully across the waters at the opposite shore. It was quite evident that he realized what a dreadful expense the club was about to be put to, and while of course there would be profit in it for him, he was sincerely sorry for them.

“I repeat,” he added, “those boats you could have had for nothing, but the others I’d have to charge you for, though of course I’ll give you a discount.”

And he blinked again, as he meditated upon whether that discount should be an eighth or one-quarter of one per cent.

“The Flying Dutchman,” he pursued, “ain’t no good for your purposes. She’s too fast. She’s built to fly by, not to stop. You’d catch up with the House-boat in a minute with her, but you’d go right on and disappear like a visionary; and as for the Ark, she’d never do—with all respect to Mr. Noah. She’s just about as suitable as any other waterlogged cattle-steamer’d be, and no more—first-rate for elephants and kangaroos, but no good for cruiser-work, and so slow she wouldn’t make a ripple high enough to drown a gnat going at the top of her speed. Furthermore, she’s got a great big hole in her bottom, where she was stove in by running afoul of—Mount Arrus-root, I believe it was called when Captain Noah went cruising with that menagerie of his.”

“That’s an unmitigated falsehood!” cried Noah, angrily. “This man talks like a professional amateur yachtsman. He has no regard for facts, but simply goes ahead and makes statements with an utter disregard of the truth. The Ark was not stove in. We beached her very successfully. I say this in defence of my seamanship, which was top-notch for my day.”

“Couldn’t sail six weeks without fouling a mountain-peak!” sneered Wren, perceiving a chance to get even.

“The hole’s there, just the same,” said Charon. “Maybe she was a centreboard, and that’s where you kept the board.”

“The hole is there because it was worn there by one of the elephants,” retorted Noah. “You get a beast like the elephant shuffling one of his fore-feet up and down, up and down, a plank for twenty-four hours a day for forty days in one of your boats, and see where your boat would be.”

“Thanks,” said Charon, calmly. “But the elephants don’t patronize my line. All the elephants I’ve ever seen in Hades waded over, except Jumbo, and he reached his trunk across, fastened on to a tree limb with it, and swung himself over. However, the Ark isn’t at all what you want, unless you are going to man her with a lot of centaurs. If that’s your intention, I’d charter her; the accommodations are just the thing for a crew of that kind.”

“Well, what do you suggest?” asked Raleigh, somewhat impatiently. “You’ve told us what we can’t do. Now tell us what we can do.”

“I’d stay right here,” said Charon, “and let the ladies rescue themselves. That’s what I’d do. I’ve had the honor of bringing ‘em over here, and I think I know ‘em pretty well. I’ve watched ‘em close, and it’s my private opinion that before many days you’ll see your club-house sailing back here, with Queen Elizabeth at the hellum, and the other ladies on the for’ard deck knittin’ and crochetin’, and tearin’ each other to pieces in a conversational way, as happy as if there never had been any Captain Kidd and his pirate crew.”

“That suggestion is impossible,” said Blackstone, rising. “Whether the relief expedition amounts to anything or not, it’s good to be set going. The ladies would never forgive us if we sat here inactive, even if they were capable of rescuing themselves. It is an accepted principle of law that this climate hath no fury like a woman left to herself, and we’ve got enough professional furies hereabouts without our aiding in augmenting the ranks. We must have a boat.”

“It’ll cost you a thousand dollars a week,” said Charon.

“I’ll subscribe fifty,” cried Hamlet.

“I’ll consult my secretary,” said Solomon, “and find out how many of my wives have been abducted, and I’ll pay ten dollars apiece for their recovery.”

“That’s liberal,” said Hawkshaw. “There are sixty-three of ‘em on board, together with eighty of his fiancées. What’s the quotation on fiancées, King Solomon?”

“Nothing,” said Solomon. “They’re not mine yet, and it’s their fathers’ business to get ‘em back. Not mine.”

Other subscriptions came pouring in, and it was not long before everybody save Shylock had put his name down for something. This some one of the more quick-witted of the spirits soon observed, and, with reckless disregard of the feelings of the Merchant of Venice, began to call: “Shylock! Shylock! How much?”

The Merchant tried to leave the pier, but his path was blocked.

“Subscribe, subscribe!” was the cry. “How much?”

“Order, gentlemen, order!” said Sir Walter, rising and holding a bottle aloft. “A black person by the name of Friday, a valet of our friend Mr. Crusoe, has just handed me this bottle, which he picked up ten minutes ago on the bank of the river a few miles distant. It contains a bit of paper, and may perhaps give us a clew based upon something more substantial than even the wonderful theories of our new brother Holmes.”

A deathly silence followed the chairman’s words, as Sir Walter drew a cork-screw from his pocket and opened the bottle. He extracted the paper, and, as he had surmised, it proved to be a message from the missing vessel. His face brightening with a smile of relief, Sir Walter read, aloud:

“Have just emerged into the Atlantic. Club in hands of Kidd and forty ruffians. One hundred and eighty-three ladies on board. Headed for the Azores. Send aid at once. All well except Xanthippe, who is seasick in the billiard-room. (Signed) Portia.”

“Aha!” cried Hawkshaw. “That shows how valuable the Holmes theory is.”

“Precisely,” said Holmes. “No woman knows anything about seafaring, but Portia is right. The ship is headed for the Azores, which is the first tack needed in a windward sail for London under the present conditions.”

The reply was greeted with cheers, and when they subsided the cry for Shylock’s subscription began again, but he declined.

“I had intended to put up a thousand ducats,” he said, defiantly, “but with that woman Portia on board I won’t give a red obolus!” and with that he wrapped his cloak about him and stalked off into the gathering shadows of the wood.

And so the funds were raised without the aid of Shylock, and the shapely twin-screw steamer the Gehenna was chartered of Charon, and put under the command of Mr. Sherlock Holmes, who, after he had thanked the company for their confidence, walked abstractedly away, observing in strictest confidence to himself that he had done well to prepare that bottle beforehand and bribe Crusoe’s man to find it.

“For now,” he said, with a chuckle, “I can get back to earth again free of cost on my own hook, whether my eminent inventor wants me there or not. I never approved of his killing me off as he did at the very height of my popularity.”

Meanwhile the ladies were not having such a bad time, after all. Once having gained possession of the House-boat, they were loath to think of ever having to give it up again, and it is an open question in my mind if they would not have made off with it themselves had Captain Kidd and his men not done it for them.

“I’ll never forgive these men for their selfishness in monopolizing all this,” said Elizabeth, with a vicious stroke of a billiard-cue, which missed the cue-ball and tore a right angle in the cloth. “It is not right.”

“No,” said Portia. “It is all wrong; and when we get back home I’m going to give my beloved Bassanio a piece of my mind; and if he doesn’t give in to me, I’ll reverse my decision in the famous case of Shylock versus Antonio.”

“Then I sincerely hope he doesn’t give in,” retorted Cleopatra, “for I swear by all my auburn locks that that was the very worst bit of injustice ever perpetrated. Mr. Shakespeare confided to me one night, at one of Mrs. Cæsar’s card-parties, that he regarded that as the biggest joke he ever wrote, and Judge Blackstone observed to Antony that the decision wouldn’t have held in any court of equity outside of Venice. If you owe a man a thousand ducats, and it costs you three thousand to get them, that’s your affair, not his. If it cost Antonio every drop of his bluest blood to pay the pound of flesh, it was Antonio’s affair, not Shylock’s. However, the world applauds you as a great jurist, when you have nothing more than a woman’s keen instinct for sentimental technicalities.”

“It would have made a horrid play, though, if it had gone on,” shuddered Elizabeth.

“That may be, but, carried out realistically, it would have done away with a raft of bad actors,” said Cleopatra. “I’m half sorry it didn’t go on, and I’m sure it wouldn’t have been any worse than compelling Brutus to fall on his sword until he resembles a chicken liver en brochette, as is done in that Julius Cæsar play.”

“Well, I’m very glad I did it,” snapped Portia.

“I should think you would be,” said Cleopatra. “If you hadn’t done it, you’d never have been known. What was that?”

The boat had given a slight lurch.

“Didn’t you hear a shuffling noise up on deck, Portia?” asked the Egyptian Queen.

“I thought I did, and it seemed as if the vessel had moved a bit,” returned Portia, nervously; for, like most women in an advanced state of development, she had become a martyr to her nerves.

“It was merely the wash from one of Charon’s new ferry-boats, I fancy,” said Elizabeth, calmly. “It’s disgusting, the way that old fellow allows these modern innovations to be brought in here! As if the old paddle-boats he used to carry shades in weren’t good enough for the immigrants of this age! Really this Styx River is losing a great deal of its charm. Sir Walter and I were upset, while out rowing one day last summer, by the waves kicked up by one of Charon’s excursion steamers going up the river with a party of picnickers from the city—the Greater Gehenna Chowder Club, I believe it was—on board of her. One might just as well live in the midst of the turmoil of a great city as try to get uninterrupted quiet here in the suburbs in these days. Charon isn’t content to get rich slowly; he must make money by the barrelful, if he has to sacrifice all the comfort of everybody living on this river. Anybody’d think he was an American, the way he goes on; and everybody else here is the same way. The Erebeans are getting to be a race of shopkeepers.”

“I think myself,” sighed Cleopatra, “that Hades is being spoiled by the introduction of American ideas—it is getting by far too democratic for my tastes; and if it isn’t stopped, it’s my belief that the best people will stop coming here. Take Madame Récamier’s salon as it is now and compare it with what it used to be! In the early days, after her arrival here, everybody went because it was the swell thing, and you’d be sure of meeting the intellectually elect. On the one hand you’d find Sophocles; on the other, Cicero; across the room would be Horace chatting gayly with some such person as myself. Great warriors, from Alexander to Bonaparte, were there, and glad of the opportunity to be there, too; statesmen like Macchiavelli; artists like Cellini or Tintoretto. You couldn’t move without stepping on the toes of genius. But now all is different. The money-getting instinct has been aroused within them all, with the result that when I invited Mozart to meet a few friends at dinner at my place last autumn, he sent me a card stating his terms for dinners. Let me see, I think I have it with me; I’ve kept it by me for fear of losing it, it is such a complete revelation of the actual condition of affairs in this locality. Ah! this is it,” she added, taking a small bit of paste-board from her card-case. “Read that.”

The card was passed about, and all the ladies were much astonished—and naturally so, for it ran this wise:

NOTICE TO HOSTESSES.

Owing to the very great, constantly growing, and at times vexatious demands upon his time socially,

HERR WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

takes this method of announcing to his friends that on and after January 1, 1897, his terms for functions will be as follows:

| Marks. | |

| Dinners with conversation on the Theory of Music | 500 |

| Dinners with conversation on the Theory of Music, illustrated | 750 |

| Dinners without any conversation | 300 |

| Receptions, public, with music | 1000 |

| Receptions, private, with music | 750 |

| Encores (single) | 100 |

| Three encores for | 150 |

| Autographs | 10 |

Positively no Invitations for Five-o’Clock Teas or Morning Musicales considered.

“Well, I declare!” tittered Elizabeth, as she read. “Isn’t that extraordinary? He’s got the three-name craze, too!”

“It’s perfectly ridiculous,” said Cleopatra. “But it’s fairer than Artemus Ward’s plan. Mozart gives notice of his intentions to charge you; but with Ward it’s different. He comes, and afterwards sends a bill for his fun. Why, only last week I got a ‘quarterly statement’ from him showing a charge against me of thirty-eight dollars for humorous remarks made to my guests at a little chafing-dish party I gave in honor of Balzac, and, worst of all, he had marked it ‘Please remit.’ Even Antony, when he wrote a sonnet to my eyebrow, wouldn’t let me have it until he had heard whether or not Boswell wanted it for publication in the Gossip. With Rubens giving chalk-talks for pay, Phidias doing ‘Five-minute Masterpieces in Putty’ for suburban lyceums, and all the illustrious in other lines turning their genius to account through the entertainment bureaus, it’s impossible to have a salon now.”

“You are indeed right,” said Madame Récamier, sadly. “Those were palmy days when genius was satisfied with chicken salad and lemonade. I shall never forget those nights when the wit and wisdom of all time were—ah—were on tap at my house, if I may so speak, at a cost to me of lights and supper. Now the only people who will come for nothing are those we used to think of paying to stay away. Boswell is always ready, but you can’t run a salon on Boswell.”

“Well,” said Portia, “I sincerely hope that you won’t give up the functions altogether, because I have always found them most delightful. It is still possible to have lights and supper.”

“I have a plan for next winter,” said Madame Récamier, “but I suppose I shall be accused of going into the commercial side of it if I adopt it. The plan is, briefly, to incorporate my salon. That’s an idea worthy of an American, I admit; but if I don’t do it I’ll have to give it up entirely, which, as you intimate, would be too bad. An incorporated salon, however, would be a grand thing, if only because it would perpetuate the salon. ‘The Récamier Salon (Limited)’ would be a most excellent title, and, suitably capitalized, would enable us to pay our lions sufficiently. Private enterprise is powerless under modern conditions. It’s as much as I can afford to pay for a dinner, without running up an expense account for guests; and unless we get up a salon trust, as it were, the whole affair must go to the wall.”

“How would you make it pay?” asked Portia. “I can’t see where your dividends would come from.”

“That is simple enough,” said Madame Récamier. “We could put up a large reception-hall with a portion of our capital, and advertise a series of nights—say one a week throughout the season. These would be Warriors’ Night, Story-tellers’ Night, Poets’ Night, Chafing-dish Night under the charge of Brillat-Savarin, and so on. It would be understood that on these particular evenings the most interesting people in certain lines would be present, and would mix with outsiders, who should be admitted only on payment of a certain sum of money. The commonplace inhabitants of this country could thus meet the truly great; and if I know them well, as I think I do, they’ll pay readily for the privilege. The obscure love to rub up against the famous here as well as they do on earth.”

“You’d run a sort of Social Zoo?” suggested Elizabeth.

“Precisely; and provide entertainment for private residences too. An advertisement in Boswell’s paper, which everybody buys—”

“And which nobody reads,” said Portia.

“They read the advertisements,” retorted Madame Récamier. “As I was saying, an advertisement could be placed in Boswell’s paper as follows: ‘Are you giving a Function? Do you want Talent? Get your Genius at the Récamier Salon (Limited).’ It would be simply magnificent as a business enterprise. The common herd would be tickled to death if they could get great people at their homes, even if they had to pay roundly for them.”

“It would look well in the society notes, wouldn’t it, if Mr. John Boggs gave a reception, and at the close of the account it said, ‘The supper was furnished by Calizetti, and the genius by the Récamier Salon (Limited)’?” suggested Elizabeth, scornfully.

“I must admit,” replied the French lady, “that you call up an unpleasant possibility, but I don’t really see what else we can do if we want to preserve the salon idea. Somebody has told these talented people that they have a commercial value, and they are availing themselves of the demand.”

“It is a sad age!” sighed Elizabeth.

“Well, all I’ve got to say is just this,” put in Xanthippe: “You people who get up functions have brought this condition of affairs on yourselves. You were not satisfied to go ahead and indulge your passion for lions in a moderate fashion. Take the case of Demosthenes last winter, for instance. His wife told me that he dined at home three times during the winter. The rest of the time he was out, here, there, and everywhere, making after-dinner speeches. The saving on his dinner bills didn’t pay his pebble account, much less remunerate him for his time, and the fearful expense of nervous energy to which he was subjected. It was as much as she could do, she said, to keep him from shaving one side of his head, so that he couldn’t go out, the way he used to do in Athens when he was afraid he would be invited out and couldn’t scare up a decent excuse for refusing.”

“Did he do that?” cried Elizabeth, with a roar of laughter.

“So the cyclopædias say. It’s a good plan, too,” said Xanthippe. “Though Socrates never had to do it. When I got the notion Socrates was going out too much, I used to hide his dress clothes. Then there was the case of Rubens. He gave a Carbon Talk at the Sforza’s Thursday Night Club, merely to oblige Madame Sforza, and three weeks later discovered that she had sold his pictures to pay for her gown! You people simply run it into the ground. You kill the goose that when taken at the flood leads on to fortune. It advertises you, does the lion no good, and he is expected to be satisfied with confectionery, material and theoretical. If they are getting tired of candy and compliments, it’s because you have forced too much of it upon them.”

“They like it, just the same,” retorted Récamier. “A genius likes nothing better than the sound of his own voice, when he feels that it is falling on aristocratic ears. The social laurel rests pleasantly on many a noble brow.”

“True,” said Xanthippe. “But when a man gets a pile of Christmas wreaths a mile high on his head, he begins to wonder what they will bring on the market. An occasional wreath is very nice, but by the ton they are apt to weigh on his mind. Up to a certain point notoriety is like a woman, and a man is apt to love it; but when it becomes exacting, demanding instead of permitting itself to be courted, it loses its charm.”

“That is Socratic in its wisdom,” smiled Portia.

“But Xanthippic in its origin,” returned Xanthippe. “No man ever gave me my ideas.”

As Xanthippe spoke, Lucretia Borgia burst into the room.

“Hurry and save yourselves!” she cried. “The boat has broken loose from her moorings, and is floating down the stream. If we don’t hurry up and do something, we’ll drift out to sea!”

“What!” cried Cleopatra, dropping her cue in terror, and rushing for the stairs. “I was certain I felt a slight motion. You said it was the wash from one of Charon’s barges, Elizabeth.”

“I thought it was,” said Elizabeth, following closely after.

“Well, it wasn’t,” moaned Lucretia Borgia. “Calpurnia just looked out of the window and discovered that we were in mid-stream.”

The ladies crowded anxiously about the stair and attempted to ascend, Cleopatra in the van; but as the Egyptian Queen reached the doorway to the upper deck, the door opened, and the hard features of Captain Kidd were thrust roughly through, and his strident voice rang out through the gathering gloom. “Pipe my eye for a sardine if we haven’t captured a female seminary!” he cried.

And one by one the ladies, in terror, shrank back into the billiard-room, while Kidd, overcome by surprise, slammed the door to, and retreated into the darkness of the forward deck to consult with his followers as to “what next.”

“Here’s a kettle of fish!” said Kidd, pulling his chin whisker in perplexity as he and his fellow-pirates gathered about the capstan to discuss the situation. “I’m blessed if in all my experience I ever sailed athwart anything like it afore! Pirating with a lot of low-down ruffians like you gentlemen is bad enough, but on a craft loaded to the water’s edge with advanced women—I’ve half a mind to turn back.”

“If you do, you swim—we’ll not turn back with you,” retorted Abeuchapeta, whom, in honor of his prowess, Kidd had appointed executive officer of the House-boat. “I have no desire to be mutinous, Captain Kidd, but I have not embarked upon this enterprise for a pleasure sail down the Styx. I am out for business. If you had thirty thousand women on board, still should I not turn back.”

“But what shall we do with ‘em?” pleaded Kidd. “Where can we go without attracting attention? Who’s going to feed ‘em? Who’s going to dress ‘em? Who’s going to keep ‘em in bonnets? You don’t know anything about these creatures, my dear Abeuchapeta; and, by-the-way, can’t we arbitrate that name of yours? It would be fearful to remember in the excitement of a fight.”

“Call him Ab,” suggested Sir Henry Morgan, with an ill-concealed sneer, for he was deeply jealous of Abeuchapeta’s preferral.

“If you do I’ll call you Morgue, and change your appearance to fit,” retorted Abeuchapeta, angrily.

“By the beards of all my sainted Buccaneers,” began Morgan, springing angrily to his feet, “I’ll have your life!”

“Gentlemen! Gentlemen—my noble ruffians!” expostulated Kidd. “Come, come; this will never do! I must have no quarrelling among my aides. This is no time for divisions in our councils. An entirely unexpected element has entered into our affairs, and it behooveth us to act in concert. It is no light matter—”

“Excuse me, captain,” said Abeuchapeta, “but that is where you and I do not agree. We’ve got our ship and we’ve got our crew, and in addition we find that the Fates have thrown in a hundred or more women to act as ballast. Now I, for one, do not fear a woman. We can set them to work. There is plenty for them to do keeping things tidy; and if we get into a very hard fight, and come out of the mêlée somewhat the worse for wear, it will be a blessing to have ‘em along to mend our togas, sew buttons on our uniforms, and darn our hosiery.”

Morgan laughed sarcastically. “When did you flourish, if ever, colonel?” he asked.

“Do you refer to me?” queried Abeuchapeta, with a frown.

“You have guessed correctly,” replied Morgan, icily. “I have quite forgotten your date; were you a success in the year one, or when?”

“Admiral Abeuchapeta, Sir Henry,” interposed Kidd, fearing a further outbreak of hostilities—“Admiral Abeuchapeta was the terror of the seas in the seventh century, and what he undertook to do he did, and his piratical enterprises were carried on on a scale of magnificence which is without parallel off the comic-opera stage. He never went forth without at least seventy galleys and a hundred other vessels.”

Abeuchapeta drew himself up proudly.

“Six-ninety-eight was my great year,” he said.

“That’s what I thought,” said Morgan. “That is to say, you got your ideas of women twelve hundred years ago, and the ladies have changed somewhat since that time. I have great respect for you, sir, as a ruffian. I have no doubt that as a ruffian you are a complete success, but when it comes to ‘feminology’ you are sailing in unknown waters. The study of women, my dear Abeuchadnezzar—”

“Peta,” retorted Abeuchapeta, irritably.

“I stand corrected. The study of women, my dear Peter,” said Morgan, with a wink at Conrad, which fortunately the seventh-century pirate did not see, else there would have been an open break—“the study of women is more difficult than that of astronomy; there may be two stars alike, but all women are unique. Because she was this, that, or the other thing in your day does not prove that she is any one of those things in our day—in fact, it proves the contrary. Why, I venture even to say that no individual woman is alike.”

“That’s rather a hazy thought,” said Kidd, scratching his head in a puzzled sort of way.

“I mean that she’s different from herself at different times,” said Morgan. “What is it the poet called her?—‘an infinite variety show,’ or something of that sort; a perpetual vaudeville—a continuous performance, as it were, from twelve to twelve.”

“Morgan is right, admiral!” put in Conrad the corsair, acting temporarily as bo’sun. “The times are sadly changed, and woman is no longer what she was. She is hardly what she is, much less what she was. The Roman Gynæceum would be an impossibility to-day. You might as well expect Delilah to open a barbershop on board this boat as ask any of these advanced females below-stairs to sew buttons on a pirate’s uniform after a fray, or to keep the fringe on his epaulets curled. They’re no longer sewing-machines—they are Keeley motors for mystery and perpetual motion. Women have views now—they are no longer content to be looked at merely; they must see for themselves; and the more they see, the more they wish to domesticate man and emancipate woman. It’s my private opinion that if we are to get along with them at all the best thing to do is to let ‘em alone. I have always found I was better off in the abstract, and if this question is going to be settled in a purely democratic fashion by submitting it to a vote, I’ll vote for any measure which involves leaving them strictly to themselves. They’re nothing but a lot of ghosts anyhow, like ourselves, and we can pretend we don’t see them.”

“If that could be, it would be excellent,” said Morgan; “but it is impossible. For a pirate of the Byronic order, my dear Conrad, you are strangely unversed in the ways of the sex which cheers but not inebriates. We can no more ignore their presence upon this boat than we can expect whales to spout kerosene. In the first place, it would be excessively impolite of us to cut them—to decline to speak to them if they should address us. We may be pirates, ruffians, cutthroats, but I hope we shall never forget that we are gentlemen.”

“The whole situation is rather contrary to etiquette, don’t you think?” suggested Conrad. “There’s nobody to introduce us, and I can’t really see how we can do otherwise than ignore them. I certainly am not going to stand on deck and make eyes at them, to try and pick up an acquaintance with them, even if I am of a Byronic strain.”

“You forget,” said Kidd, “two essential features of the situation. These women are at present—or shortly will be, when they realize their situation—in distress, and a true gentleman may always fly to the rescue of a distressed female; and, the second point, we shall soon be on the seas, and I understand that on the fashionable transatlantic lines it is now considered de rigueur to speak to anybody you choose to. The introduction business isn’t going to stand in my way.”

“Well, may I ask,” put in Abeuchapeta, “just what it is that is worrying you? You said something about feeding them, and dressing them, and keeping them in bonnets. I fancy there’s fish enough in the sea to feed ‘em; and as for their gowns and hats, they can make ‘em themselves. Every woman is a milliner at heart.”

“Exactly, and we’ll have to pay the milliners. That is what bothers me. I was going to lead this expedition to London, Paris, and New York, admiral. That is where the money is, and to get it you’ve got to go ashore, to headquarters. You cannot nowadays find it on the high seas. Modern civilization,” said Kidd, “has ruined the pirate’s business. The latest news from the other world has really opened my eyes to certain facts that I never dreamed of. The conditions of the day of which I speak are interestingly shown in the experience of our friend Hawkins here. Captain Hawkins, would you have any objection to stating to these gentlemen the condition of affairs which led you to give up piracy on the high seas?”

“Not the slightest, Captain Kidd,” returned Captain Hawkins, who was a recent arrival in Hades. “It is a sad little story, and it gives me a pain for to think on it, but none the less I’ll tell it, since you ask me. When I were a mere boy, fellow-pirates, I had but one ambition, due to my readin’, which was confined to stories of a Sunday-school nater—to become somethin’ different from the little Willies an’ the clever Tommies what I read about therein. They was all good, an’ they went to their reward too soon in life for me, who even in them days regarded death as a stuffy an’ unpleasant diversion. Learnin’ at an early period that virtue was its only reward, an’ a-wish-in’ others, I says to myself: ‘Jim,’ says I, ‘if you wishes to become a magnet in this village, be sinful. If so be as you are a good boy, an’ kind to your sister an’ all other animals, you’ll end up as a prosperous father with fifteen hundred a year sure, with never no hope for no public preferment beyond bein’ made the superintendent of the Sunday-school; but if so be as how you’re bad, you may become famous, an’ go to Congress, an’ have your picture in the Sunday noospapers.’ So I looks around for books tellin’ how to get ‘Famous in Fifty Ways,’ an’ after due reflection I settles in my mind that to be a pirate’s just the thing for me, seein’ as how it’s both profitable an’ healthy. Passin’ over details, let me tell you that I became a pirate. I ran away to sea, an’ by dint of perseverance, as the Sunday-school books useter say, in my badness I soon became the centre of a evil lot; an’ when I says to ‘em, ‘Boys, I wants to be a pirate chief,’ they hollers back, loud like, ‘Jim, we’re with you,’ an’ they was. For years I was the terror of the Venezuelan Gulf, the Spanish Main, an’ the Pacific seas, but there was precious little money into it. The best pay I got was from a Sunday noospaper, which paid me well to sign an article on ‘Modern Piracy’ which I didn’t write. Finally business got so bad the crew began to murmur, an’ I was at my wits’ ends to please ‘em; when one mornin’, havin’ passed a restless night, I picks up a noospaper and sees in it that ‘Next Saturday’s steamer is a weritable treasure-ship, takin’ out twelve million dollars, and the jewels of a certain prima donna valued at five hundred thousand.’ ‘Here’s my chance,’ says I, an’ I goes to sea and lies in wait for the steamer. I captures her easy, my crew bein’ hungry, an’ fightin’ according like. We steals the box a-hold-in’ the jewels an’ the bag containin’ the millions, hustles back to our own ship, an’ makes for our rondyvoo, me with two bullets in my leg, four o’ my crew killed, and one engin’ of my ship disabled by a shot—but happy. Twelve an’ a half millions at one break is enough to make anybody happy.”

“I should say so,” said Abeuchapeta, with an ecstatic shake of his head. “I didn’t get that in all my career.”

“Nor I,” sighed Kidd. “But go on, Hawkins.”

“Well, as I says,” continued Captain Hawkins, “we goes to the rondyvoo to look over our booty. ‘Captain ‘Awkins,’ says my valet—for I was a swell pirate, gents, an’ never travelled nowhere without a man to keep my clothes brushed and the proper wrinkles in my trousers—‘this ‘ere twelve millions,’ says he, ‘is werry light,’ says he, carryin’ the bag ashore. ‘I don’t care how light it is, so long as it’s twelve millions, Henderson,’ says I; but my heart sinks inside o’ me at his words, an’ the minute we lands I sits down to investigate right there on the beach. I opens the bag, an’ it’s the one I was after—but the twelve millions!”

“Weren’t there?” cried Conrad.

“Yes, they was there,” sighed Hawkins, “but every bloomin’ million was represented by a certified check, an’ payable in London!”

“By Jingo!” cried Morgan. “What fearful luck! But you had the prima donna’s jewels.”

“Yes,” said Hawkins, with a moan. “But they was like all other prima donna’s jewels—for advertisin’ purposes only, an’ made o’ gum-arabic!”

“Horrible!” said Abeuchapeta. “And the crew, what did they say?”

“They was a crew of a few words,” sighed Hawkins. “Werry few words, an’ not a civil word in the lot—mostly adjectives of a profane kind. When I told ‘em what had happened, they got mad at Fortune for a-jiltin’ of ‘em, an’—well, I came here. I was ’sas’inated that werry night!”

“They killed you?” cried Morgan.

“A dozen times,” nodded Hawkins. “They always was a lavish lot. I met death in all its most horrid forms. First they stabbed me, then they shot me, then they clubbed me, and so on, endin’ up with a lynchin’—but I didn’t mind much after the first, which hurt a bit. But now that I’m here I’m glad it happened. This life is sort of less responsible than that other. You can’t hurt a ghost by shooting him, because there ain’t nothing to hurt, an’ I must say I like bein’ a mere vision what everybody can see through.”

“All of which interesting tale proves what?” queried Abeuchapeta.