The Project Gutenberg EBook of McClure's Magazine, Volume VI, No. 3. February 1896, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: McClure's Magazine, Volume VI, No. 3. February 1896 Author: Various Release Date: October 18, 2004 [EBook #13788] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MCCLURE'S MAGAZINE *** Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Richard J. Shiffer and the PG Online Distributed Proofreading Team.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN. By Ida M. Tarbell. 213

Lincoln's Life at New Salem from 1832 to 1836. 213

Looking for Work. 213

Decides to Buy a Store. 213

He Begins to Study Law. 221

Berry and Lincoln Get a Tavern License. 226

The Firm Hires a Clerk. 227

Lincoln Appointed Postmaster. 228

A New Opening. 228

Surveying with a Grapevine. 230

Business Reverses. 230

The Kindness Shown Lincoln in New Salem. 232

Lincoln's Acquaintance in Sangamon County Is Extended. 232

He Finally Decides on a Legal Career. 233

Lincoln Enters the Illinois Assembly. 234

The Story of Ann Rutledge. 236

Abraham Lincoln at Twenty-six Years of Age. 238

A GOVERNMENT OFFICIAL. By Ian Maclean. 241

THE FASTEST RAILROAD RUN EVER MADE. By Harry Perry Robinson. 247

A CENTURY OF PAINTING. By Will H. Low. 256

THE TRAGEDY OF GARFIELD'S ADMINISTRATION. By Murat Halstead. 269

Garfield's Administration. 274

The Garfields in the White House. 277

Last Interview with President Garfield. 278

THE VICTORY OF THE GRAND DUKE OF MITTENHEIM. By Anthony Hope. 280

Chapter II. 288

CHAPTERS FROM A LIFE. By Elizabeth Stuart Phelps. 293

THE TOUCHSTONE. By Robert Louis Stevenson. 300

MAGAZINE NOTES. 304

Mrs. Humphry Ward—Dr. Jowett. 304

Three Hundred Thousand. 304

Our Own Printing Establishment. 304

Anthony Hope's New Novel. 304

The Life of Lincoln. 304

The Early Life of Lincoln. 304

Elizabeth Stuart Phelps. 304

"The Sabine Women"—A Correction. 304

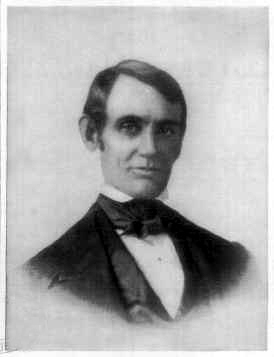

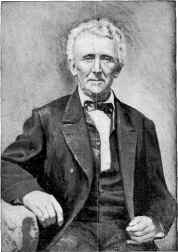

THE EARLIEST PORTRAIT OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

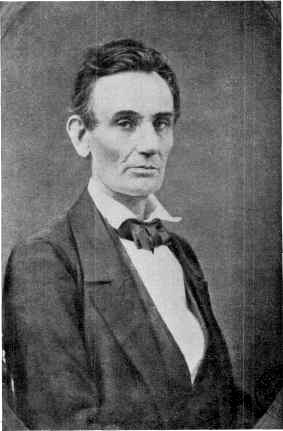

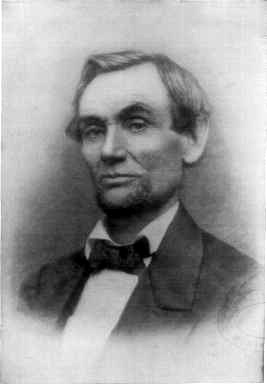

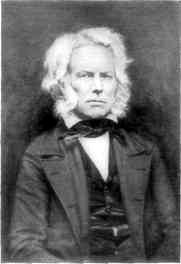

LINCOLN IN THE SUMMER OF 1860.

THE STATE-HOUSE AT VANDALIA, ILLINOIS.

LINCOLN'S SURVEYING INSTRUMENTS.

FACSIMILE OF A TAVERN LICENSE ISSUED TO BERRY AND LINCOLN.

BERRY AND LINCOLN'S STORE IN 1895.

DANIEL GREEN BURNER, BERRY AND LINCOLN'S CLERK.

SAMUEL HILL--AT WHOSE STORE LINCOLN KEPT THE POST-OFFICE.

MARY ANN RUTLEDGE, MOTHER OF ANN MAYES RUTLEDGE.

JOHN CALHOUN, UNDER WHOM LINCOLN LEARNED SURVEYING.

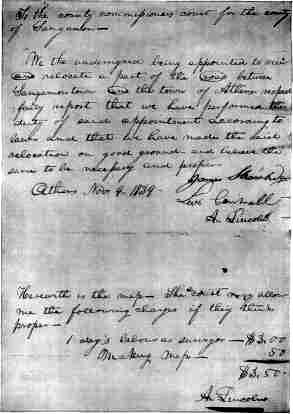

REPORT OF A ROAD SURVEY BY LINCOLN.

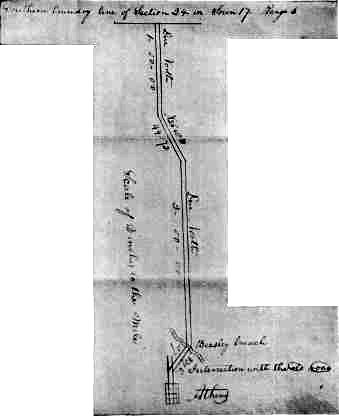

A MAP MADE BY LINCOLN OF A PIECE OF ROAD IN MENARD COUNTY.

A WAYSIDE WELL NEAR NEW SALEM, KNOWN AS "ANN RUTLEDGE'S WELL."

JOSEPH DUNCAN, GOVERNOR OF ILLINOIS DURING LINCOLN'S FIRST TERM.

GRAVE OF ANN RUTLEDGE IN OAKLAND CEMETERY.

"I WENT UP TO MR. PERKINS'S ROOM WITHOUT CEREMONY."

"HE HAD THE JOLLIEST LITTLE DINNER READY YOU EVER SAW."

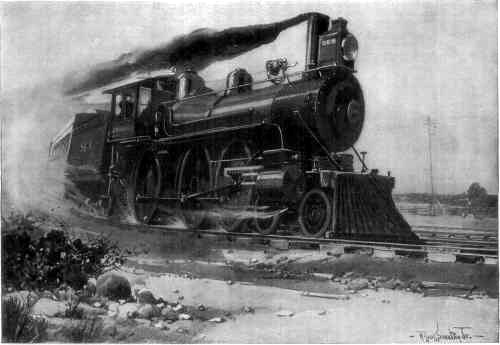

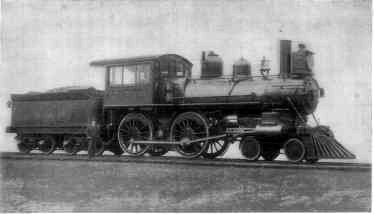

VIEW BACK ON THE TRACK WHEN TRAIN WAS RUNNING AT ABOUT 80 MPH.

THE ENGINEERS WHO BROUGHT THE TRAIN FROM CHICAGO TO CLEVELAND.

J.R. GARNER, ENGINEER FROM CLEVELAND TO ERIE.

WILLIAM TUNKEY, ENGINEER FROM ERIE TO BUFFALO.

GEORGE ROMNEY, PAINTER OF "THE PARSON'S DAUGHTER."

FLATFORD MILL, ON THE RIVER STOUR.

THE "FIGHTING TEMERAIRE" TUGGED TO HER LAST BERTH.

JOSEPH MALLORD WILLIAM TURNER.

PEACE--BURIAL AT SEA OF THE BODY OF SIR DAVID WILKIE.

MISS BARRON, AFTERWARDS MRS. RAMSEY.

PORTRAIT OF A BROTHER AND SISTER.

GARFIELD IN 1881, WHILE PRESIDENT. AGE 49.

GARFIELD IN 1867, WITH HIS DAUGHTER.

"FROM THE LONG GRASS BY THE RIVER'S EDGE A YOUNG MAN SPRANG UP."

"'YOU ARE THE BEAUTY OF THE WORLD,' HE ANSWERED SMILING."

"'LISTEN!' SHE CRIED, SPRINGING TO HER FEET."

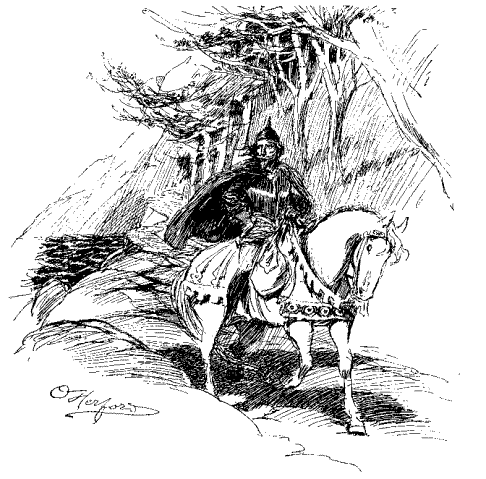

"HE LEANED FROM HIS SADDLE AS HE DASHED BY."

PROFESSOR AUSTIN PHELPS, FATHER OF ELIZABETH STUART PHELPS.

PROFESSOR M. STUART PHELPS, ELDEST SON OF PROFESSOR AUSTIN PHELPS.

"HE WAS A GRAVE MAN, AND BESIDE HIM STOOD HIS DAUGHTER."

"'MAID,' QUOTH HE, 'I WOULD FAIN MARRY YOU.'"

"ALL THAT DAY HE RODE, AND HIS MIND WAS QUIET."

BERRY AND LINCOLN'S GROCERY.—A SET OF BLACKSTONE'S COMMENTARIES.—BERRY AND LINCOLN TAKE OUT A TAVERN LICENSE.—THE POSTMASTER OF NEW SALEM IN 1833.—LINCOLN BECOMES DEPUTY SURVEYOR.—THE FAILURE OF BERRY AND LINCOLN.—ELECTIONEERING IN ILLINOIS.—LINCOLN CHOSEN ASSEMBLYMAN.—BEGINS TO STUDY LAW.—THE ILLINOIS STATE LEGISLATURE IN 1834.—THE STORY OF ANN RUTLEDGE.—ABRAHAM LINCOLN AT TWENTY-SIX YEARS OF AGE.

Embodying special studies in Lincoln's life at New Salem by J. McCan Davis.

T was in August, 1832, that Lincoln made his unsuccessful canvass for the Illinois Assembly. The election over, he began to look for work. One of his friends, an admirer of his physical strength, advised him to become a blacksmith, but it was a trade which would afford little leisure for study, and for meeting and talking with men; and he had already resolved, it is evident, that books and men were essential to him. The only employment to be had in New Salem which seemed to offer both support and the opportunities he sought, was clerking in a store; and he applied for a place successively at all of the stores then doing business in New Salem. But they were in greater need of customers than of clerks. The business had been greatly overdone. In the fall of 1832 there were at least four stores in New Salem. The most pretentious was that of Hill and McNeill, which carried a large line of dry goods. The three others, owned by the Herndon Brothers, Reuben Radford, and James Rutledge, were groceries.

Failing to secure employment at any of these establishments, Lincoln, though without money enough to pay a week's board in advance, resolved to buy a store. He was not long in finding an opportunity to purchase. James Herndon had already sold out his half interest in Herndon Brothers' store to William F. Berry; and Rowan Herndon, not getting along well with Berry, was only too glad to find a purchaser of his half in the person of "Abe" Lincoln. Berry was as poor as Lincoln; but that was not a serious obstacle, for their notes were accepted for the Herndon stock of goods. They had barely hung out their sign when something happened which threw another store into their hands. Reuben Radford had made himself obnoxious to the Clary's Grove Boys, and one night they broke in his doors and windows, and overturned his counters and sugar barrels. It was too much for Radford, and he sold out next day to William G. Green for a four-hundred-dollar note signed by Green. At the latter's request, Lincoln made an inventory of the stock, and offered him six hundred and fifty dollars for it—a proposition which was cheerfully accepted. Berry and Lincoln, being unable to pay cash, assumed the four-hundred-dollar note payable to Radford, and gave Green their joint note for two hundred and fifty dollars. The little grocery owned by James Rutledge was the next to succumb. Berry and Lincoln bought it at a bargain, their joint note taking the place of cash. The three stocks were consolidated. Their aggregate cost must have been not less than fifteen hundred dollars. Berry and Lincoln had secured a monopoly of the grocery business in New Salem. Within a few weeks two penniless men had become the proprietors of three stores, and had stopped buying only because there were no more to purchase.

[pg 214]

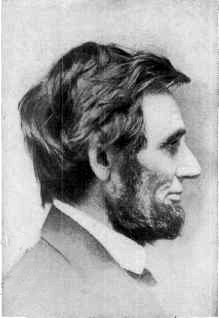

From a daguerreotype in the possession of the Hon. Robert T. Lincoln, taken before Lincoln was forty, and first published in the McCLURE'S Life of Lincoln. Of the sixty or more portraits of Lincoln which will be published in this series of articles, thirty, at least, will be absolutely new to our readers; and of these thirty none is more important than this early portrait. It is generally believed that Lincoln was not over thirty-five years old when this daguerreotype was taken, and it is certainly true that it is the face of Lincoln as a young man. "About thirty would be the general verdict," says Mr. Murat Halstead in an editorial in the Brooklyn "Standard-Union," "if it were not that the daguerreotype was unknown when Lincoln was of that age. It does not seem, however, that he could have been more than thirty-five, and for that age the youthfulness of the portrait is wonderful. This is a new Lincoln, and far more attractive, in a sense, than anything the public has possessed. This is the portrait of a remarkably handsome man.... The head is magnificent, the eyes deep and generous, the mouth sensitive, the whole expression something delicate, tender, pathetic, poetic. This was the young man with whom the phantoms of romance dallied, the young man who recited poems and was fanciful and speculative, and in love and despair, but upon whose brow there already gleamed the illumination of intellect, the inspiration of patriotism. There were vast possibilities in this young man's face. He could have gone anywhere and done anything. He might have been a military chieftain, a novelist, a poet, a philosopher, ah! a hero, a martyr—and, yes, this young man might have been—he even was Abraham Lincoln! This was he with the world before him. It is good fortune to have the magical revelation of the youth of the man the world venerates. This look into his eyes, into his soul—not before he knew sorrow, but long before the world knew him—and to feel that it is worthy to be what it is, and that we are better acquainted with him and love him the more, is something beyond price."

From a photograph in the collection of H.W. Fay, De Kalb, Illinois. The original was made by S.M. Fassett, of Chicago; the negative was destroyed in the Chicago fire. This picture was made at the solicitation of D.B. Cook, who says that Mrs. Lincoln pronounced it the best likeness she had ever seen of her husband. Rajon used the Fassett picture as the original of his etching, and Kruell has made a fine engraving of it.

From a copy (made by E.A. Bromley of the Minneapolis "Journal" staff) of a photograph owned by Mrs. Cyrus Aldrich, whose husband, now dead, was a congressman from Minnesota. In the summer of 1860 Mr. M.C. Tuttle, a photographer of St. Paul, wrote to Mr. Lincoln requesting that he have a negative taken and sent to him for local use in the campaign. The request was granted, but the negative was broken in transit. On learning of the accident, Mr. Lincoln sat again, and with the second negative he sent a jocular note wherein he referred to the fact, disclosed by the picture, that in the interval he had "got a new coat." A few copies of the picture were made by Mr. Tuttle, and distributed among the Republican editors of the State. It has never before been reproduced. Mrs. Aldrich's copy was presented to her by William H. Seward, when he was entertained at the Aldrich homestead (now the Minneapolis City Hospital) in September, 1860. A fine copy of this same photograph is in the possession of Mr. Ward Monroe, of Jersey City, N.J.

William F. Berry, the partner of Lincoln, was the son of a Presbyterian minister, the Rev. John Berry, who lived on Rock Creek, five miles from New Salem. The son had strayed from the footsteps of the father, for he was a hard drinker, a gambler, a fighter, and "a very wicked young man." Lincoln cannot in truth be said to have chosen such a partner, but rather to have accepted him from the force of circumstances. It required only a little time to make it plain that the partnership was wholly uncongenial. Lincoln displayed little business capacity. He trusted largely to Berry; and Berry rapidly squandered the profits of the business in riotous living. Lincoln loved books as Berry loved liquor, and hour after hour he was stretched out on the counter of the store or under a shade tree, reading Shakespeare or Burns.

[pg 217]

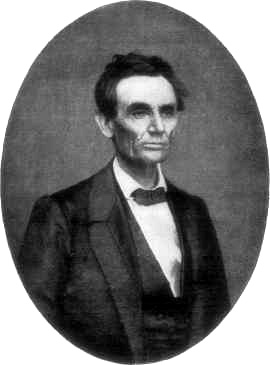

From a photograph in the collection of H.W. Fay of De Kalb, Illinois, taken probably in Springfield early in 1861. It is supposed to have been the first, or at least one of the first, portraits made of Mr. Lincoln after he began to wear a beard. As is well known, his face was smooth until about the end of 1860; and when he first allowed his beard to grow, it became a topic of newspaper comment, and even of caricature. A pretty story relating to Lincoln's adoption of a beard is more or less familiar. A letter written to the editor of the present Life, under date of December 6, 1895, by Mrs. Grace Bedell Billings, tells this story, of which she herself as a little girl was the heroine, in a most charming way. The letter will be found printed in full at the end of this article, on page 240.

His thorough acquaintance with the works of these two writers dates from this period. In New Salem there was one of those curious individuals sometimes found in frontier settlements, half poet, half loafer, incapable of earning a living in any steady employment, yet familiar with good literature and capable of enjoying it—Jack Kelso. He repeated passages from Shakespeare and Burns incessantly over the odd jobs he undertook or as he idled by the streams—for he was a famous fisherman—and Lincoln soon became one of his constant companions. The taste he formed in company with Kelso he retained through life. William D. Kelley tells an incident which shows that Lincoln had a really intimate knowledge of Shakespeare. Mr. Kelley had taken McDonough, an actor, to call at the White House; and Lincoln began the conversation by saying:

[pg 218]

From a photograph loaned by Mr. Frank A. Brown of Minneapolis, Minnesota. This beautiful photograph was taken, probably early in 1861, by Alexander Hesler of Chicago. It was used by Leonard W. Volk, the sculptor, in his studies of Lincoln, and closely resembles the fine etching by T. Johnson.

"'I am very glad to meet you, Mr. McDonough, and am grateful to Kelley for bringing you in so early, for I want you to tell me something about Shakespeare's plays as they are constructed for the stage. You can imagine that I do not get much time to study such matters, but I recently had a couple of talks with Hackett—Baron Hackett, as they call him—who is famous as Jack Falstaff, but from whom I elicited few satisfactory replies, though I probed him with a good many questions.'

[pg 219]

Vandalia was the State capital of Illinois for twenty years, and three different State-houses were built and occupied there. The first, a two-story frame structure, was burned down December 9, 1823. The second was a brick building, and was erected at a cost of $12,381.50, of which the citizens of Vandalia contributed $3,000. The agitation for the removal of the capital to Springfield began in 1833, and in the summer of 1836 the people of Vandalia, becoming alarmed at the prospect of their little city's losing its prestige as the seat of the State government, tore down the old capitol (much complaint being made about its condition), and put up a new one at a cost of $16,000. The tide was too great to be checked; but after the "Long Nine" had secured the passage of the bill taking the capital to Springfield, the money which the Vandalia people had expended was refunded. The State-house shown in this picture was the third and last one. In it Lincoln served as a legislator. Ceasing to be the capitol July 4, 1839, it was converted into a court-house for Fayette County, and is still so used.—J. McCan Davis.

After Lincoln gave up surveying, he sold his instruments to John B. Gum, afterward county surveyor of Menard County. Mr. Gum kept them until a few years ago, when he presented the instruments to the Lincoln Monument Association, and they are now on exhibition at the monument in Springfield, Ill.

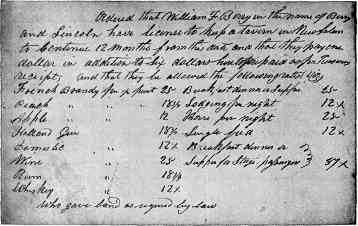

The only tavern in New Salem in 1833 was that kept by James Rutledge—a two-story log-structure of five rooms, standing just across the street from Berry and Lincoln's store. Here Lincoln boarded. It seems entirely probable that he may have had an ambition to get into the tavern business, and that he and Berry obtained a license with that end in view, possibly hoping to make satisfactory terms for the purchase of the Rutledge hostelry. The tavern of sixty years ago, besides answering the purposes of the modern hotel, was the dramshop of the frontier. The business was one which, in Illinois, the law strictly regulated. Tavern-keepers were required to pay a license fee, and to give bonds to insure their good behavior. Minors were not to be harbored, nor did the law permit liquor to be sold to them; and the sale to slaves of any liquors "or strong drink, mixed or unmixed, either within or without doors," was likewise forbidden. Nor could the poor Indian get any "fire-water" at the tavern or the grocery. If a tavern-keeper violated the law, two-thirds of the fine assessed against him went to the poor people of the county. The Rutledge tavern was the only one at New Salem of which we have any authentic account. It was kept by others besides Mr. Rutledge; for a time by Henry Onstott the cooper, and then by Nelson Alley, and possibly there were other landlords; but nothing can be more certain than that Lincoln was not one of them. The few surviving inhabitants of the vanished village, and of the country round about, have a clear recollection of Berry and Lincoln's store—of how it looked, and of what things were sold in it; but not one has been found with the faintest remembrance of a tavern kept by Lincoln, or by Berry, or by both. Stage passengers jolting into New Salem sixty-two years ago must, if Lincoln was an inn-keeper, have partaken of his hospitality by the score; but if they did, they all died many, many years ago, or have all maintained an unaccountable and most perplexing silence.—J. McCan Davis.

"'Your last suggestion,' said Mr. Lincoln, 'carries with it greater weight than anything Mr. Hackett suggested, but the first is no reason at all;' and after reading another passage, he said, 'This is not withheld, and where it passes current there can be no reason for withholding the other.'... And, as if feeling the impropriety of preferring the player to the parson, [there was a clergyman in the room] he turned to the chaplain and said: 'From your calling it is probable that you do not know that the acting plays which people crowd to hear are not always those planned by their reputed authors. Thus, take the stage edition of "Richard III." It opens with a passage from "Henry VI.," after which come portions of "Richard III.," then another scene from "Henry VI.," and the finest soliloquy in the play, if we may judge from the many quotations it furnishes, and the frequency with which it is heard in amateur exhibitions, was never seen by Shakespeare, but was written—was it not, Mr. McDonough?—after his death, by Colley Cibber."

"Having disposed, for the present, of questions relating to the stage editions of the plays, he recurred to his standard copy, and, to the evident surprise of Mr. McDonough, read or repeated from memory extracts from several of the plays, some of which embraced a number of lines.

"It must not be supposed that Mr. Lincoln's poetical studies had been confined to his plays. He interspersed his remarks with extracts striking from their similarity to, or contrast with, something of Shakespeare's, [pg 221] from Byron, Rogers, Campbell, Moore, and other English poets."1

From a recent photograph by C.S. McCullough, Petersburg, Illinois. The little frame store-building occupied by Berry and Lincoln at New Salem is now standing at Petersburg, Illinois, in the rear of L.W. Bishop's gun-shop. Its history after 1834 is somewhat obscure, but there is no reason for doubting its identity. According to tradition it was bought by Robert Bishop, the father of the present owner, about 1835, from Mr. Lincoln himself; but it is difficult to reconcile this legend with the sale of the store to the Trent brothers, unless, upon the flight of the latter from the country and the closing of the store, the building, through the leniency of creditors, was allowed to revert to Mr. Lincoln, in which event he no doubt sold it at the first opportunity and applied the proceeds to the payment of the debts of the firm. When Mr. Bishop bought the store building, he removed it to Petersburg. It is said that the removal was made in part by Lincoln himself; that the job was first undertaken by one of the Bales, but that, encountering some difficulty, he called upon Lincoln to assist him, which Lincoln did. The structure was first set up adjacent to Mr. Bishop's house, and converted into a gun-shop. Later it was removed to a place on the public square; and soon after the breaking out of the late war, Mr. Bishop, erecting a new building, pushed Lincoln's store into the back-yard, and there it still stands. Soon after the assassination of Mr. Lincoln, the front door was presented to some one in Springfield, and has long since been lost sight of. It is remembered by Mr. Bishop that in this door there was an opening for the reception of letters—a circumstance of importance as tending to establish the genuineness of the building, when it is remembered that Lincoln was postmaster while he kept the store. The structure, as it stands to-day, is about eighteen feet long, twelve feet in width, and ten feet in height. The back room, however, has disappeared, so that the building as it stood when occupied by Berry and Lincoln was somewhat longer. Of the original building there only remain the frame-work, the black-walnut weather-boarding on the front end and the ceiling of sycamore boards. One entire side has been torn away by relic-hunters. In recent years the building has been used as a sort of store-room. Just after a big fire in Petersburg some time ago, the city council condemned the Lincoln store building and ordered it demolished. Under this order a portion of one side was torn down, when Mr. Bishop persuaded the city authorities to desist, upon giving a guarantee that if Lincoln's store ever caught fire he would be responsible for any loss which might ensue.—J. McCan Davis.

It was not only Burns and Shakespeare that interfered with the grocery-keeping: Lincoln had begun seriously to read law. His first acquaintance with the subject had been made when he was a mere lad in Indiana, and a copy of the "Revised Statutes of Indiana" had fallen into his hands. The very copy he used is still in existence and, fortunately, in hands where it is safe. The book was owned by Mr. David Turnham, of Gentryville, and was given in 1865 by him to Mr. Herndon, who placed it in the Lincoln Memorial collection of Chicago. In December, 1894, this collection was sold in Philadelphia, and the "Statutes of Indiana" was bought by Mr. William Hoffman Winters, Librarian of the New York Law Institute, and through his courtesy I have been allowed to examine it. The book is worn, the title page is gone and a few leaves from the end are missing. The title page of a duplicate volume which Mr. Winters kindly showed me reads: "The Revised Laws of Indiana adopted and enacted by the General Assembly at their eighth session. To which are prefixed the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of the United States, the Constitution of the State of Indiana, and sundry other documents connected with the Political History of the Territory and State of Indiana. Arranged and published by authority of the General Assembly. Corydon, Printed by Carpenter and Douglass, 1824."

[pg 222]

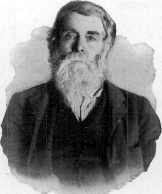

From a recent photograph. Mr. Burner was Berry and Lincoln's clerk. He lived at New Salem from 1829 to 1834. Lincoln for many months lodged with his father, Isaac Burner, and he and Lincoln slept in the same bed. He now lives on a farm near Galesburg, Illinois, past eighty.

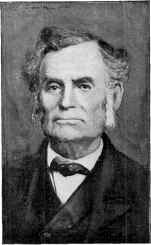

From a photograph in the possession of the Hon. W.J. Orendorff, of Canton, Illinois. John M. Cameron, a Cumberland Presbyterian minister, and a devout, sincere, and courageous man, was held in the highest esteem by his neighbors. Yet, according to Daniel Green Burner, Berry and Lincoln's clerk—and the fact is mentioned merely as illustrating a universal custom among the pioneers—"John Cameron always kept a barrel of whiskey in the house." He was a powerful man physically, and a typical frontiersman. He was born in Kentucky in 1791, and, with his wife, moved to Illinois in 1815. He settled in Sangamon County in 1818, and in 1829 took up his abode in a cabin on a hill overlooking the Sangamon River, and, with James Rutledge, founded the town of New Salem.

According to tradition, Lincoln, for a time, lived with the Camerons. In the early thirties they moved to Fulton County, Illinois; then, in 1841 or 1842, to Iowa; and finally, in 1849, to California. In California they lived to a ripe old age—Mrs. Cameron dying in 1875, and her husband following her three years later. They had twelve children, eleven of whom were girls. In 1886 there were living nine of these children, fifty grandchildren, and one hundred and one great-grandchildren. Mr. Cameron is said to have officiated at the funeral of Ann Rutledge in 1835.—J. McCan Davis.

From a photograph taken at Jacksonville, Illinois, about thirty years ago. James Short lived on Sand Ridge, a few miles north of New Salem, and Lincoln was a frequent visitor at his house. When Lincoln's horse and surveying instruments were levied upon by a creditor and sold, Mr. Short bought them in, and made Lincoln a present of them. Lincoln, when President, made his old friend an Indian agent in California. Mr. Short, in the course of his life, was happily married five times. He died in Iowa many years ago. His acquaintance with Lincoln began in rather an interesting way. His sister, who lived in New Salem, had made Lincoln a pair of jeans trousers. The material supplied by Lincoln was scant, and the trousers came out conspicuously short in the legs. One day when James Short was visiting with his sister, he pointed to a man walking down the street, and asked, "Who is that man in the short breeches." "That is Lincoln," the sister replied; and Mr. Short went out and introduced himself to Lincoln.—J. McCan Davis.

Coleman Smoot was born in Virginia, February 13, 1794; removed to Kentucky when a child; married Rebecca Wright March 17, 1817; came to Illinois in 1831, and lived on a farm across the Sangamon River from New Salem until his death, March 21, 1876. He accumulated an immense fortune. Lincoln met him for the first time in Offutt's store in 1831. "Smoot," said Lincoln, "I am disappointed in you; I expected to see a man as ugly as old Probst," referring to a man reputed to be the homeliest in the county. "And I am disappointed," replied Smoot; "I had expected to see a good-looking man when I saw you." From that moment they were warm friends. After Lincoln's election to the legislature in 1834, he called on Smoot, and said, "I want to buy some clothes and fix up a little, so that I can make a decent appearance in the legislature; and I want you to loan me $200." The loan was cheerfully made, and of course was subsequently repaid.—J. McCan Davis.

From an old daguerreotype. Samuel Hill was among the earliest inhabitants of New Salem. He opened a general store there in partnership with John McNeill,—the John McNeill who became betrothed to Ann Rutledge, and whose real name was afterwards discovered to be John McNamar. When McNeill left New Salem and went East, Mr. Hill became sole proprietor of the store. He also owned the carding machine at New Salem. Lincoln, after going out of the grocery business, made his headquarters at Samuel Hill's store. There he kept the post-office, entertained the loungers, and on busy days helped Mr. Hill wait on customers. Mr. Hill is said to have once courted Ann Rutledge himself, but he did not receive the encouragement which was bestowed upon his partner, McNeill. In 1839 he moved his store to Petersburg, and died there in 1857. In 1835 he married Miss Parthenia W. Nance, who still lives at Petersburg.—J. McCan Davis.

From an old tintype. Mary Ann Rutledge was the wife of James Rutledge and the mother of Ann. She was born October 21, 1787, and reared in Kentucky. She lived to be ninety-one years of age, dying in Iowa December 26, 1878. The Rutledges left New Salem in 1833 or 1834, moving to a farm a few miles northward. On this farm Ann Rutledge died August 25, 1835; and here also, three months later (December 3, 1835), died her father, broken-hearted, no doubt, by the bereavement. In the following year the family moved to Fulton County, Illinois, and some three years later to Birmingham, Iowa. Of James Rutledge there is no portrait in existence. He was born in South Carolina, May 11, 1781. He and his sons, John and David, served in the Black Hawk War.—J. McCan Davis.

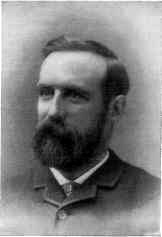

From a steel engraving in the possession of R.W. Diller, Springfield, Illinois. John Calhoun was born in Boston, Massachusetts, October 14, 1806; removed to the Mohawk Valley, New York, in 1821; was educated at Canajoharie Academy, and studied law. In 1830 he removed to Springfield, Illinois, and after serving in the Black Hawk War was appointed Surveyor of Sangamon County. He was married there December 29, 1831, to Miss Sarah Cutter. He was a Democratic Representative in 1838; Clerk of the House in 1840; circuit clerk in 1842; Democratic presidential elector in 1844; candidate for Governor before the Democratic State convention in 1846; Mayor of Springfield in 1849, 1850, and 1851; a candidate for Congress in 1852, and in the same year again a Democratic presidential elector. In 1854, President Pierce appointed him Surveyor-General of Kansas, and he became conspicuous in Kansas politics. He was president of the Lecompton Convention. He died at St. Joseph, Missouri, October 25, 1859. Mr. Frederick Hawn, who was his boyhood friend, and afterward married a sister of Calhoun's wife, is now living at Leavenworth, Kansas, at the age of eighty-five years. In an interesting letter to the writer, he says: "It has been related that Calhoun induced Lincoln to study surveying in order to become his deputy. Presuming that he was ready to graduate and receive his commission, he called on Calhoun, then living with his father-in-law, Seth R. Cutter, on Upper Lick Creek. After the interview was concluded, Mr. Lincoln, about to depart, remarked: 'Calhoun, I am entirely unable to repay you for your generosity at present. All that I have you see on me, except a quarter of a dollar in my pocket.' This is a family tradition. However, my wife, then a miss of sixteen, says, while I am writing this sketch, that she distinctly remembers this interview. After Lincoln was gone she says she and her sister, Mrs. Calhoun, commenced making jocular remarks about his uncanny appearance, in the presence of Calhoun, to which in substance he made this rejoinder: 'For all that, he is no common man.' My wife believes these were the exact words."—J. McCan Davis.

We know from Dennis Hanks, from Mr. Turnham, to whom the book belonged, and from other associates of Lincoln's at the time, that he read this book intently and discussed its contents intelligently. It was a remarkable volume for a thoughtful lad whose mind had been fired already by the history of Washington; for it opened with that wonderful document, the Declaration of Independence, a document which became, as Mr. John G. Nicolay says, "his political chart and inspiration." Following the Declaration of Independence was the Constitution of the United States, the Act of Virginia passed in 1783 by which the "Territory North Westward of the river Ohio" was conveyed to the United States, and the Ordinance of 1787 for governing this territory, containing that clause on which Lincoln in the future based many an argument on the slavery question. This article, No. 6 of the Ordinance, reads: "There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted: provided always, that any person escaping into the same, from whom labour or service is lawfully claimed in any one of the original States, such fugitive may be lawfully reclaimed, and conveyed to the person claiming his or her labour or service, as aforesaid."

These saddle-bags, now in the Lincoln Monument at Springfield, are said to have been used by Lincoln while he was a surveyor.

Following this was the Constitution and the Revised Laws of Indiana, three hundred and seventy-five pages of five hundred words each of statutes—enough law, if thoroughly digested, to make a respectable lawyer. When Lincoln finished this book, as he had probably before he was eighteen, we have reason to believe that he understood the principles on which the nation was founded, how the State of Indiana came into being, and how it was governed. His understanding of the subject was clear and practical, and he applied it in his reading, thinking, and discussion.

Photographed for McCLURE'S MAGAZINE from the original, now on file in the County Clerk's office, Springfield, Illinois. The survey here reported was made in pursuance of an order of the County Commissioners' Court, September 1, 1834, in which Lincoln was designated as the surveyor.

It was after he had read the Laws of Indiana that Lincoln had free access to the library of his admirer, Judge John Pitcher of Rockport, Indiana, where undoubtedly he examined many law-books. But from the time he left Indiana in 1830 he had no legal reading until one day soon after the grocery was started, when there happened one of those trivial incidents which so often turn the current of a life. It is best told in Mr. Lincoln's own words.2 "One day a man who was migrating to the West drove up in front of my store with a wagon which contained his family and household plunder. He asked me if I would buy an old barrel, for which he had no room in his wagon, and which he said contained nothing of special value. I did not want it, but to oblige him I bought it, and paid him, I think, half a dollar for it. Without further examination, I put it away in the store, and forgot all about it. Some time after, in overhauling things, I came upon the barrel, and emptying it upon the floor to see what it contained, I found at the bottom of the rubbish a complete edition of Blackstone's Commentaries. I began to read those famous works, and I had plenty of time; for, during the long summer days, when the farmers were busy with their crops, my customers were few and far between. The more I read"—this he said with unusual emphasis—"the more intensely interested I became. Never in my whole life was my mind so thoroughly absorbed. I read until I devoured them."

[pg 226]

Photographed from the original for McCLURE'S MAGAZINE. This map, which, as here reproduced, is about one-half the size of the original, accompanied Lincoln's report of the survey of a part of the road between Athens and Sangamon town. For making this map, Lincoln received fifty cents. The road evidently was located "on good ground," and was "necessary and proper," as the report says, for it is still the main travelled highway leading into the country south of Athens, Menard County.

But all this was fatal to business, and by spring it was evident that something must be done to stimulate the grocery sales.

On the 6th of March, 1833, the County Commissioners' Court of Sangamon County granted the firm of Berry and Lincoln a license to keep a tavern at New Salem. A copy of this license is here given:

Ordered that William F. Berry, in the name of Berry and Lincoln, have a license to keep a tavern in New Salem to continue 12 months from this date, and that they pay one dollar in addition to the six dollars heretofore paid as per Treasurer's receipt, and that they be allowed the following rates (viz.):

French Brandy per 1/2 pt. 25 Peach " " " . 18-3/4 Apple " " " . 12 Holland Gin " " . 18-3/4 Domestic " " . 12-1/2 Wine " " . 25 Rum " " . 18-3/4 Whisky " " . 12-1/2 Breakfast, din'r or supper 25 Lodging per night........ 12-1/2 Horse per night.......... 25 Single feed.............. 12-1/2 Breakfast, dinner or supper for Stage Passengers..... 37-1/2 who gave bond as required by law.

It is probable that the license was procured to enable the firm to retail the liquors which they had in stock, and not for keeping a tavern. In a community in which liquor-drinking was practically universal, at a time when whiskey was as legitimate an article of merchandise as coffee or calico, when no family was without a jug, when the minister of the gospel could [pg 227] take his "dram" without any breach of propriety, it is not surprising that a reputable young man should have been found selling whiskey. Liquor was sold at all groceries, but it could not be lawfully sold in a smaller quantity than one quart. The law, however, was not always rigidly observed, and it was the custom of store-keepers to "set up" the drinks to their patrons. Each of the three groceries which Berry and Lincoln acquired had the usual supply of liquors, and the combined stock must have amounted almost to a superabundance. It was only good business that they should seek a way to dispose of the surplus quickly and profitably—an end which could be best accomplished by selling it over the counter by the glass. Lawfully to do this required a tavern license; and it is a warrantable conclusion that such was the chief aim of Berry and Lincoln in procuring a franchise of this character. We are fortified in this conclusion by the coincidence that three other grocers of New Salem—William Clary, Henry Sincoe, and George Warberton—were among those who took out tavern licenses. To secure the lawful privilege of selling whiskey by the "dram" was no doubt their purpose; for their "taverns" were as mythical as the inn of Berry and Lincoln.

At the granting of a tavern license, the applicants therefor were required by law to file a bond. The bond given in the case of Berry and Lincoln was as follows:

Know all men by these presents, we, William F. Berry, Abraham Lincoln and John Bowling Green, are held and firmly bound unto the County Commissioners of Sangamon County in the full sum of three hundred dollars to which payment well and truly to be made we bind ourselves, our heirs, executors and administrators firmly by these presents, sealed with our seal and dated this 6th day of March A.D. 1833. Now the condition of this obligation is such that Whereas the said Berry & Lincoln has obtained a license from the County Commissioners Court to keep a tavern in the Town of New Salem to continue one year. Now if the said Berry & Lincoln shall be of good behavior and observe all the laws of this State relative to tavern keepers—then this obligation to be void or otherwise remain in full force.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN [Seal]

WM. F. BERRY [Seal]

BOWLING GREEN [Seal]

This bond appears to have been written by the clerk of the Commissioners' Court; and Lincoln's name was signed by some one other than himself, very likely by his partner Berry.

The license seems to have stimulated the business, for the firm concluded to hire a clerk. The young man who secured this position was Daniel Green Burner, son of Isaac Burner, at whose house Lincoln for a time boarded. He is still living on a farm near Galesburg, Illinois, and is in the eighty-second year of his age. "The store building of Berry and Lincoln," says Mr. Burner, "was a frame building, not very large, one story in height, and contained two rooms. In the little back room Lincoln had a fireplace and a bed. There is where we slept. I clerked in the store through the winter of 1834, up to the 1st of March. While I was there they had nothing for sale but liquors. They may have had some groceries before that, but I am certain they had none then. I used to sell whiskey over their counter at six cents a glass—and charged it, too. N.A. Garland started a store, and Lincoln wanted Berry to ask his father for a loan, so they could buy out Garland; but Berry refused, saying this was one of the last things he would think of doing."

Among the other persons yet living who were residents with Lincoln of New Salem or its near neighborhood are Mrs. Parthenia [pg 228] W. Hill, aged seventy-nine years, widow of Samuel Hill, the New Salem merchant; James McGrady Rutledge, aged eighty-one years; John Potter, aged eighty-seven years; and Thomas Watkins, aged seventy-one years—all now living at Petersburg, Illinois. Mrs. Hill, a woman of more than ordinary intelligence, did not become a resident of New Salem until 1835, the year in which she was married. Lincoln had then gone out of business, but she knew much of his store. "Berry and Lincoln," she says, "did not keep any dry goods. They had a grocery, and I have always understood they sold whiskey." Mr. Rutledge, a nephew of James Rutledge the tavern-keeper, has a vivid recollection of the store. He says: "I have been in Berry and Lincoln's store many a time. The building was a frame—one of the few frame buildings in New Salem. There were two rooms, and in the small back room they kept their whiskey. They had pretty much everything, except dry goods—sugar, coffee, some crockery, a few pairs of shoes (not many), some farming implements, and the like. Whiskey, of course, was a necessary part of their stock. I remember one transaction in particular which I had with them. I sold the firm a load of wheat, which they turned over to the mill." Mr. Potter, who remembers the morning when Lincoln, then a stranger on his way to New Salem, stopped at his father's house and ate breakfast, knows less about the store, but says: "It was a grocery, and they sold whiskey, of course." Thomas Watkins says that the store contained "a little candy, tobacco, sugar, and coffee, and the like;" though Mr. Watkins, being then a small boy, and living a mile in the country, was not a frequent visitor at the store.

Business was not so brisk, however, in Berry and Lincoln's grocery, even after the license was granted, that the junior partner did not welcome an appointment as postmaster which he received in May, 1833. The appointment of a Whig by a Democratic administration seems to have been made without comment. "The office was too insignificant to make his politics an objection," say the autobiographical notes. The duties of the new office were not arduous, for letters were few, and their comings far between. At that date the mails were carried by four-horse post-coaches from city to city, and on horseback from central points into the country towns. The rates of postage were high. A single-sheet letter carried thirty miles or under cost six cents; thirty to eighty miles, ten cents; eighty to one hundred and fifty miles, twelve and one-half cents; one hundred and fifty to four hundred miles, eighteen and one-half cents; over four hundred miles, twenty-five cents. A copy of this magazine sent from New York to New Salem would have cost fully twenty-five cents. The mail was irregular in coming as well as light in its contents. Though supposed to arrive twice a week, it sometimes happened that a fortnight or more passed without any mail. Under these conditions the New Salem post-office was not a serious care.

A large number of the patrons of the office lived in the country—many of them miles away—but generally Lincoln delivered their letters at their doors. These letters he would carefully place in the crown of his hat, and distribute them from house to house. Thus it was in a measure true that he kept the New Salem post-office in his hat. The habit of carrying papers in his hat clung to Lincoln; for, many years later, when he was a practising lawyer in Springfield, he apologized for failing to answer a letter promptly, by explaining: "When I received your letter I put it in my old hat, and buying a new one the next day, the old one was set aside, and so the letter was lost sight of for a time."

But whether the mail was delivered by the postmaster himself, or the recipient came to the store to inquire, "Anything for me?" it was the habit "to stop and visit awhile." He who received a letter read it and told the contents; if he had a newspaper, usually the postmaster could tell him in advance what it contained, for one of the perquisites of the early post-office was the privilege of reading all printed matter before delivering it. Every day, then, Lincoln's acquaintance in New Salem, through his position as postmaster, became more intimate.

As the summer of 1833 went on, the condition of the store became more and more unsatisfactory. As the position of postmaster brought in only a small revenue, Lincoln was forced to take any odd work he could get. He helped in other stores in the town, split rails, and looked after the mill; but all this yielded only a scant and uncertain support, and when in the fall he [pg 229] had an opportunity to learn surveying, he accepted it eagerly.

The condition of affairs in Illinois in the thirties made a demand for the services of surveyors. The immigration had been phenomenal. There were thousands of farms to be surveyed and thousands of "corners" to be located. Speculators bought up large tracts, and mapped out cities on paper. It was years before the first railroad was built in Illinois, and as all inland travelling was on horseback or in the stage-coach, each year hundreds of miles of wagon road were opened through woods and swamps and prairies. As the county of Sangamon was large and eagerly sought by immigrants, the county surveyor in 1833, one John Calhoun, needed deputies; but in a country so new it was no easy matter to find men with the requisite capacity.

From a photograph by C.S. McCullough, Petersburg, Illinois. Concord cemetery lies seven miles northwest of the old town of New Salem, in a secluded place, surrounded by woods and pastures, away from the world. In this lonely spot Ann Rutledge was at first laid to rest. Thither Lincoln is said to have often come alone, and "sat in silence for hours at a time;" and it was to Ann Rutledge's grave here that he pointed and said: "There my heart lies buried." The old cemetery suffered the melancholy fate of New Salem. It became a neglected, deserted spot. The graves were lost in weeds, and a heavy growth of trees kept out the sun and filled the place with gloom. A dozen years ago this picture was taken. It was a blustery day in the autumn, and the weeds and trees were swaying before a furious gale. No other picture of the place, taken while Ann Rutledge was buried there, is known to be in existence. A picture of a cemetery, with the name of Ann Rutledge on a high, flat tombstone, has been published in two or three books; but it is not genuine, the "stone" being nothing more than a board improvised for the occasion. The grave of Ann Rutledge was never honored with a stone until the body was taken up in 1890 and removed to Oakland cemetery, a mile southwest of Petersburg.—J. McCan Davis.

With Lincoln, Calhoun had little, if any, personal acquaintance, for they lived twenty miles apart. Lincoln, however, had made himself known by his meteoric race for the legislature in 1832, and Calhoun had heard of him as an honest, intelligent, and trustworthy young man. One day he sent word to Lincoln by Pollard Simmons, who lived in the New Salem neighborhood, that he had decided to appoint him a deputy surveyor if he would accept the position.

Going into the woods, Simmons found Lincoln engaged in his old occupation of making rails. The two sat down together on a log, and Simmons told Lincoln what Calhoun had said. It was a surprise to Lincoln. Calhoun was a "Jackson man;" he was for Clay. What did he know about surveying, and why should a Democratic official offer him a position of any kind? He immediately went to Springfield, and had a talk with Calhoun. He would not accept the appointment, he said, unless he had the assurance that it involved no political obligation, and that he might continue to express his political opinions as freely and frequently as he chose. This assurance was given. The only difficulty then in the way was the fact that he knew absolutely nothing of surveying. But Calhoun, of course, understood this, and agreed that he should have time to learn.

[pg 230]With the promptness of action with which he always undertook anything he had to do, he procured Flint and Gibson's treatise on surveying, and sought Mentor Graham for help. At a sacrifice of some time, the schoolmaster aided him to a partial mastery of the intricate subject. Lincoln worked literally day and night, sitting up night after night until the crowing of the cock warned him of the approaching dawn. So hard did he study that his friends were greatly concerned at his haggard face. But in six weeks he had mastered all the books within reach relating to the subject—a task which, under ordinary circumstances, would hardly have been achieved in as many months. Reporting to Calhoun for duty (greatly to the amazement of that gentleman), he was at once assigned to the territory in the northwest part of the county, and the first work he did of which there is any authentic record was in January, 1834. In that month he surveyed a piece of land for Russell Godby, dating the certificate January 14, 1834, and signing it "J. Calhoun, S.S.C., by A. Lincoln."

Lincoln was frequently employed in laying out public roads, being selected for that purpose by the County Commissioners' Court. So far as can be learned from the official records, the first road he surveyed was "from Musick's Ferry on Salt Creek, via New Salem, to the county line in the direction of Jacksonville." For this he was allowed fifteen dollars for five days' service, and two dollars and fifty cents for a plat of the new road. The next road he surveyed, according to the records, was that leading from Athens to Sangamon town. This was reported to the County Commissioners' Court November 4, 1834. But road surveying was only a small portion of his work. He was more frequently employed by private individuals.

According to tradition, when he first took up the business he was too poor to buy a chain, and, instead, used a long, straight grape-vine. Probably this is a myth, though surveyors who had experience in the early days say it may be true. The chains commonly used at that time were made of iron. Constant use wore away and weakened the links, and it was no unusual thing for a chain to lengthen six inches after a year's use. "And a good grape-vine," to use the words of a veteran surveyor, "would give quite as satisfactory results as one of those old-fashioned chains."

Lincoln's surveys had the extraordinary merit of being correct. Much of the government work had been rather indifferently done, or the government corners had been imperfectly preserved, and there were frequent disputes between adjacent land-owners about boundary lines. Frequently Lincoln was called upon in such cases to find the corner in controversy. His verdict was invariably the end of the dispute, so general was the confidence in his honesty and skill. Some of these old corners located by him are still in existence. The people of Petersburg proudly remember that they live in a town which was laid out by Lincoln. This he did in 1836, and it was the work of several weeks.

Lincoln's pay as a surveyor was three dollars a day, more than he had ever before earned. Compared with the compensation for like services nowadays it seems small enough; but at that time it was really princely. The Governor of the State received a salary of only one thousand dollars a year, the Secretary of State six hundred dollars, and good board and lodging could be obtained for one dollar a week. But even three dollars a day did not enable him to meet all his financial obligations. The heavy debts of the store hung over him. The long distances he had to travel in his new employment had made it necessary to buy a horse, and for it he had gone into debt.

"My father," says Thomas Watkins of Petersburg, who remembers the circumstances well, "sold Lincoln the horse, and my recollection is that Lincoln agreed to pay him fifty dollars for it. Lincoln was a little slow in making the payments, and after he had paid all but ten dollars, my father, who was a high-strung man, became impatient, and sued him for the balance. Lincoln, of course, did not deny the debt, and raised the money and paid it. I do not often tell this," Mr. Watkins adds, "because I have always thought there never was such a man as Lincoln, and I have always been sorry father sued him."

Between his duties as deputy surveyor and postmaster, Lincoln had little leisure for the store, and its management had passed into the hands of Berry. The stock of groceries was on the wane. The numerous obligations of the firm were maturing, with no money to meet them. Both members [pg 231] of the firm, in the face of such obstacles, lost courage; and when, early in 1834, Alexander and William Trent asked if the store was for sale, an affirmative answer was eagerly given. A price was agreed upon, and the sale was made. Now, neither Alexander Trent nor his brother had any money; but as Berry and Lincoln had bought without money, it seemed only fair that they should be willing to sell on the same terms. Accordingly the notes of the Trent brothers were accepted for the purchase price, and the store was turned over to the new owners. But about the time their notes fell due the Trent brothers disappeared. The few groceries in the store were seized by creditors, and the doors were closed, never to be opened again.

Misfortunes now crowded upon Lincoln. His late partner, Berry, soon reached the end of his wild career; and one morning a farmer from the Rock Creek neighborhood drove into New Salem with the news that he was dead.

The appalling debt which had accumulated was thrown upon Lincoln's shoulders. It was then too common a fashion among men who became deluged in debt to "clear out," in the expressive language of the pioneer, as the Trents had done; but this was not Lincoln's way. He quietly settled down among the men he owed, and promised to pay them. For fifteen years he carried this burden—a load which he cheerfully and manfully bore, but one so heavy that he habitually spoke of it as the "national debt." Talking once of it to a friend, Lincoln said: "That debt was the greatest obstacle I have ever met in life; I had no way of speculating, and could not earn money except by labor, and to earn by labor eleven hundred dollars, besides my living, seemed the work of a lifetime. There was, however, but one way. I went to the creditors, and told them that if they would let me alone, I would give them all I could earn over my living, as fast as I could earn it." As late as 1848, so we are informed by Mr. Herndon, Mr. Lincoln, then a member of Congress, sent home money saved from his salary to be applied on these obligations. All the notes, with interest at the high rates then prevailing, were at last paid.

With a single exception Lincoln's creditors seem to have been lenient. One of the notes given by him came into the hands of a Mr. Van Bergen, who, when it fell due, brought suit. The amount of the judgment was more than Lincoln could pay, and his personal effects were levied upon. These consisted of his horse, saddle and bridle, and surveying instruments. James Short, a well-to-do farmer living on Sand Ridge a few miles north of New Salem, heard of the trouble which had befallen his young friend. Without advising Lincoln of his plans he attended the sale, bought in the horse and surveying instruments for one hundred and twenty dollars, and turned them over to their former owner.

Lincoln's first meeting with Douglas occurred at the State capital, Vandalia, in the winter of 1834-35, when Lincoln was serving his first term in the legislature, and Douglas was an applicant for the office of State attorney for the first judicial district of Illinois.]

Lincoln never forgot a benefactor. He not only repaid the money with interest, but nearly thirty years later remembered the kindness in a most substantial way. After Lincoln left New Salem financial reverses came to James Short, and he removed to the far West to seek his fortune anew. Early in Lincoln's presidential term he heard that "Uncle Jimmy" was living [pg 232] in California. One day Mr. Short received a letter from Washington, D.C. Tearing it open, he read the gratifying announcement that he had been commissioned an Indian agent.

The kindness of Mr. Short was not exceptional in Lincoln's New Salem career. When the store had "winked out," as he put it, and the post-office had been left without headquarters, one of his neighbors, Samuel Hill, invited the homeless postmaster into his store. There was hardly a man or woman in the community who would not have been glad to do as much. It was a simple recognition on their part of Lincoln's friendliness to them. He was what they called "obliging"—a man who instinctively did the thing which he saw would help another, no matter how trivial or homely it was. In the home of Rowan Herndon, where he had boarded when he first came to the town, he had made himself loved by his care of the children. "He nearly always had one of them around with him," says Mr. Herndon. In the Rutledge tavern, where he afterwards lived, the landlord told with appreciation how, when his house was full, Lincoln gave up his bed, went to the store, and slept on the counter, his pillow a web of calico. If a traveller "stuck in the mud" in New Salem's one street, Lincoln was always the first to help pull out the wheel. The widows praised him because he "chopped their wood;" the overworked, because he was always ready to give them a lift. It was the spontaneous, unobtrusive helpfulness of the man's nature which endeared him to everybody and which inspired a general desire to do all possible in return. There are many tales told of homely service rendered him, even by the hard-working farmers' wives around New Salem. There was not one of them who did not gladly "put on a plate" for Abe Lincoln when he appeared, or would not darn or mend for him when she knew he needed it. Hannah Armstrong, the wife of the hero of Clary's Grove, made him one of her family. "Abe would come out to our house," she said, "drink milk, eat mush, cornbread and butter, bring the children candy, and rock the cradle while I got him something to eat.... Has stayed at our house two or three weeks at a time." Lincoln's pay for his first piece of surveying came in the shape of two buckskins, and it was Hannah who "foxed" them on his trousers.

His relations were equally friendly in the better homes of the community; even at the minister's, the Rev. John Cameron's, he was perfectly at home, and Mrs. Cameron was by him affectionately called "Aunt Polly." It was not only his kindly service which made Lincoln loved; it was his sympathetic comprehension of the lives and joys and sorrows and interests of the people. Whether it was Jack Armstrong and his wrestling, Hannah and her babies, Kelso and his fishing and poetry, the schoolmaster and his books—with one and all he was at home. He possessed in an extraordinary degree the power of entering into the interests of others, a power found only in reflective, unselfish natures endowed with a humorous sense of human foibles, coupled with great tenderness of heart. Men and women amused Lincoln, but so long as they were sincere he loved them and sympathized with them. He was human in the best sense of that fine word.

Now that the store was closed and his surveying increased, Lincoln had an excellent opportunity to extend his acquaintance, for he was travelling about the country. Everywhere he won friends. The surveyor naturally was respected for his calling's sake, but the new deputy surveyor was admired for his friendly ways, his willingness to lend a hand indoors as well as out, his learning, his ambition, his independence. Throughout the county he began to be regarded as "a right smart young man." Some of his associates appear even to have comprehended his peculiarly great character and dimly to have foreseen a splendid future. "Often," says Daniel Green Burner, Berry and Lincoln's clerk in the grocery, "I have heard my brother-in-law, Dr. Duncan, say he would not be surprised if some day Abe Lincoln got to be Governor of Illinois. Lincoln," Mr. Burner adds, "was thought to know a little more than anybody else among the young people. He was a good debater, and liked it. He read much, and seemed never to forget anything."

Lincoln was fully conscious of his popularity, and it seemed to him in 1834 that he could safely venture to try again for the legislature. Accordingly he announced himself as a candidate, spending much of the summer of 1834 in electioneering. It [pg 233] was a repetition of what he had done in 1832, though on the larger scale made possible by wider acquaintance. In company with the other candidates, he rode up and down the county, making speeches in the public squares, in shady groves, now and then in a log school-house. In his speeches he soon distinguished himself by the amazing candor with which he dealt with all questions, and by his curious blending of audacity and humility. Wherever he saw a crowd of men he joined them, and he never failed to adapt himself to their point of view in asking for votes. If the degree of physical strength was their test for a candidate, he was ready to lift a weight or wrestle with the country-side champion; if the amount of grain a man could cradle would recommend him, he seized the cradle and showed the swath he could cut. The campaign was well conducted, for in August he was elected one of the four assemblymen from Sangamon. The vote at this election stood: Dawson, 1390; Lincoln, 1376; Carpenter, 1170; Stuart, 1164.3

Born in Kentucky in 1807. At twenty-one, on being admitted to the bar, he removed to Springfield, Illinois, and was soon prominent in his profession. He was a member of the legislature from 1832 to 1836. In 1838 he defeated Stephen A. Douglas for Congress, and served two terms—as a Whig. In 1863 and 1864 he served a third term—as a Democrat. He served also in the State Senate, and was a major in the Black Hawk War. He died in 1885.

The best thing which Lincoln did in the canvass of 1834 was not winning votes; it was coming to a determination to read law, not for pleasure but as a business. In his autobiographical notes he says: "During the canvass, in a private conversation Major John T. Stuart (one of his fellow-candidates) encouraged Abraham to study law. After the election he borrowed books of Stuart, took them home with him, and went at it in good earnest. He never studied with anybody." He seems to have thrown himself into the work with an almost impatient ardor. As he tramped back and forth from Springfield, twenty miles away, to get his law-books, he read sometimes forty pages or more on the way. Often he was seen wandering at random across the fields, repeating aloud the points in his last reading. The subject seemed never to be out of his mind. It was the great absorbing interest of his life. The rule he gave twenty years later to a young man who wanted to know how to become a lawyer, seems to have been the one he practised.4

Having secured a book of legal forms, he was soon able to write deeds, contracts, and all sorts of legal instruments; and he was frequently called upon by his neighbors to perform services of this kind. "In 1834," says Daniel Green Burner, Berry and Lincoln's clerk, "my father, Isaac Burner, sold out to Henry Onstott, and he wanted a deed written. I knew how handy Lincoln was that way, and suggested that we get him. We found him sitting on a stump. 'All right,' said he, when informed what we wanted. 'If you will bring me a pen and ink and a piece of paper I will write it here.' I brought him these articles, and, picking up a shingle and putting it on his knee for a desk, he wrote out the deed." As there was no practising lawyer nearer than Springfield, Lincoln was often employed to act the part of advocate before the village squire, at [pg 234] that time Bowling Green. He realized that this experience was valuable, and never, so far as known, demanded or accepted a fee for his services in these petty cases.

Justice was sometimes administered in a summary way in Squire Green's court. Precedents and the venerable rules of law had little weight. The "Squire" took judicial notice of a great many facts, often going so far as to fill, simultaneously, the two functions of witness and court. But his decisions were generally just.

James McGrady Rutledge tells a story in which several of Lincoln's old friends figure and which illustrates the legal practices of New Salem. "Jack Kelso," says Mr. Rutledge, "owned or claimed to own a white hog. It was also claimed by John Ferguson. The hog had often wandered around Bowling Green's place, and he was somewhat acquainted with it. Ferguson sued Kelso, and the case was tried before 'Squire' Green. The plaintiff produced two witnesses who testified positively that the hog belonged to him. Kelso had nothing to offer, save his own unsupported claim.

"'Are there any more witnesses?' inquired the court.

"He was informed that there were no more.

"'Well,' said 'Squire' Green, 'the two witnesses we have heard have sworn to a —— lie. I know this shoat, and I know it belongs to Jack Kelso. I therefore decide this case in his favor.'"

An extract from the record of the County Commissioners' Court illustrates the nature of the cases that came before the justice of the peace in Lincoln's day. It also shows the price put upon the privilege of working on Sunday, in 1832:

JANUARY 29, 1832.—Alexander Gibson found guilty of Sabbath-breaking and fined 12½ cents. Fine paid into court.

The session of the ninth Assembly began December 1, 1834, and Lincoln went to the capital, then Vandalia, seventy-five miles southeast of New Salem, on the Kaskaskia River, in time for the opening. Vandalia was a town which had been called into existence in 1820 especially to give the State government an abiding-place. Its very name had been chosen, it is said, because it "sounded well" for a State capital. As the tradition goes, while the commissioners were debating what they should call the town they were making, a wag suggested that it be named Vandalia, in honor of the Vandals, a tribe of Indians which, said he, had once lived on the borders of the Kaskaskia; this, he argued, would conserve a local tradition while giving a euphonous title. The commissioners, pleased with so good a suggestion, adopted the name. When Lincoln first went to Vandalia it was a town of about eight hundred inhabitants; its noteworthy features, according to Peck's "Gazetteer" of Illinois for 1834, being a brick court-house, a two-story brick edifice "used by State officers," "a neat framed house of worship for the Presbyterian Society, with a cupola and bell," "a framed meeting-house for the Methodist Society," three taverns, several stores, five lawyers, four physicians, a land office, and two newspapers. It was a much larger town than Lincoln had ever lived in before, though he was familiar with Springfield, then twice as large as Vandalia, and he had seen the cities of the Mississippi.

The Assembly which he entered was composed of eighty-one members,—twenty-six senators, fifty-five representatives. As a rule, these men were of Kentucky, Tennessee, or Virginia origin, with here and there a Frenchman. There were but few Eastern men, for there was still a strong prejudice in the State against Yankees. The close bargains and superior airs of the emigrants from New England contrasted so unpleasantly with the open-handed hospitality and the easy ways of the Southerners and French, that a pioneer's prospects were blasted at the start if he acted like a Yankee. A history of Illinois in 1837, published evidently to "boom" the State, cautioned the emigrant that if he began his life in Illinois by "affecting superior intelligence and virtue, and catechizing the people for their habits of plainness and simplicity and their apparent want of those things which he imagines indispensable to comfort," he must expect to be forever marked as "a Yankee," and to have his prospects correspondingly defeated. A "hard-shell" Baptist preacher of about this date showed the feeling of the people when he said, in preaching of the richness of the grace of the Lord: "It tuks in the isles of the sea and the uttermust part of the yeth. It embraces the Esquimaux and the Hottentots, and some, my dear brethering, go so far as to suppose that it tuks in the poor benighted Yankees, but I don't go that fur." When it came to an election of legislators, many of the people "didn't go that fur" either.

[pg 235]There was a preponderance of jean suits like Lincoln's in the Assembly, and there were coonskin caps and buckskin trousers. Nevertheless, more than one member showed a studied garb and a courtly manner. Some of the best blood of the South went into the making of Illinois, and it showed itself from the first in the Assembly. The surroundings of the legislators were quite as simple as the attire of the plainest of them. The court-house, in good old Colonial style, with square pillars and belfry, was finished with wooden desks and benches. The State furnished her law-makers no superfluities—three dollars a day, a cork inkstand, a certain number of quills, and a limited amount of stationery was all an Illinois legislator in 1834 got from his position. Scarcely more could be expected from a State whose revenues from December 1, 1834, to December 1, 1836, were only about one hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars, with expenditures during the same period amounting to less than one hundred and sixty-five thousand dollars.

Joseph Duncan, Governor of Illinois from 1834 to 1838, was born in Kentucky in 1794. The son of an officer of the regular army, he, at nineteen, became a soldier in the war of 1812, and did gallant service. He removed to Illinois in 1818, and soon became prominent in the State, serving as a major-general of militia, a State Senator, and, from 1826 to 1834, as a member of Congress, resigning from Congress to take the office of Governor. He was at first a Democrat, but afterwards became a Whig. He was a man of the highest character and public spirit. He died in 1844.

Lincoln thought little of these things, no doubt. To him the absorbing interest was the men he met. To get acquainted with them, measure them, compare himself with them, and discover wherein they were his superiors and what he could do to make good his deficiency—this was his chief occupation. The men he met were good subjects for such study. Among them were Wm. L.D. Ewing, Jesse K. Dubois, Stephen T. Logan, Theodore Ford, and Governor Duncan—men destined to play large parts in the history of the State. One whom he met that winter in Vandalia was destined to play a great part in the history of the nation—the Democratic candidate for the office of State attorney for the first judicial district of Illinois; a man four years younger than Lincoln—he was only twenty-one at the time; a new-comer, too, in the State, having arrived about a year before, under no very promising auspices either, for he had only thirty-seven cents in his pockets, and no position in view; but a man of metal, it was easy to see, for already he had risen so high in the district where he had settled, that he dared contest the office of State attorney with John J. Hardin, one of the most successful lawyers of the State. This young man was Stephen A. Douglas. He had come to Vandalia from Morgan County to conduct his campaign, and Lincoln met him first in the halls of the old court-house, where he and his friends carried on with success their contest against Hardin.

The ninth Assembly gathered in a more hopeful and ambitious mood than any of its predecessors. Illinois was feeling well. The State was free from debt. The Black Hawk War had stimulated the people greatly, for it had brought a large amount of money into circulation. In fact, the greater portion of the eight to ten million dollars the war had cost had been circulated among the Illinois volunteers. Immigration, too, was increasing at a bewildering rate. In 1835 the census showed a population of 269,974. Between 1830 and 1835 two-fifths of this number had come in. In the northeast Chicago had begun to rise. "Even for Western towns" its growth had been unusually rapid, declared Peck's "Gazetteer" of 1834; the harbor building there, the proposed Michigan and Illinois canal, the rise in town lots—all promised to the State a metropolis. To meet the rising tide of prosperity, the legislators of 1834 felt that they must devise some worthy scheme, so they chartered a new State bank with a capital of one million five hundred thousand dollars, and revived a bank which had broken twelve years before, granting it a charter of three hundred thousand dollars. [pg 236] There was no surplus money in the State to supply the capital; there were no trained bankers to guide the concern; there was no clear notion of how it was all to be done; but a banking capital of one million eight hundred thousand dollars would be a good thing in the State, they were sure; and if the East could be made to believe in Illinois as much as her legislators believed in her, the stocks would go, and so the banks were chartered.

But even more important to the State than banks was a highway. For thirteen years plans of the Illinois and Michigan canal had been constantly before the Assembly. Surveys had been ordered, estimates reported, the advantages extolled, but nothing had been done. Now, however, the Assembly, flushed by the first thrill of the coming "boom," decided to authorize a loan of a half-million on the credit of the State. Lincoln favored both these measures. He did not, however, do anything especially noteworthy for either of the bills, nor was the record he made in other directions at all remarkable. He was placed on the committee of public accounts and expenditures, and attended meetings with great fidelity. His first act as a member was to give notice that he would ask leave to introduce a bill limiting the jurisdiction of justices of the peace—a measure which he succeeded in carrying through. He followed this by a motion to change the rules, so that it should not be in order to offer amendments to any bill after the third reading, which was not agreed to; though the same rule, in effect, was adopted some years later, and is to this day in force in both branches of the Illinois Assembly. He next made a motion to take from the table a report which had been submitted by his committee, which met a like fate. His first resolution, relating to a State revenue to be derived from the sales of the public lands, was denied a reference, and laid upon the table. Neither as a speaker nor an organizer did he make any especial impression on the body.

In the spring of 1835 the young representative from Sangamon returned to New Salem to take up his duties as postmaster and deputy surveyor, and to resume his law studies. He exchanged his rather exalted position for the humbler one with a light heart. New Salem held all that was dearest in the world to him at that moment, and he went back to the poor little town with a hope, which he had once supposed honor forbade his acknowledging even to himself, glowing warmly in his heart. He loved a young girl of that town, and now for the first time, though he had known her since he first came to New Salem, was he free to tell his love.

One of the most prominent families of the settlement in 1831, when Lincoln first appeared there, was that of James Rutledge. The head of the house was one of the founders of New Salem, and at that time the keeper of the village tavern. He was a high-minded man, of a warm and generous nature, and had the universal respect of the community. He was a South Carolinian by birth, but had lived many years in Kentucky before coming to Illinois. Rutledge came of a distinguished family: one of his ancestors signed the Declaration of Independence; another was Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States by appointment of Washington, and another was a conspicuous leader in the American Congress.

The third of the nine children in the Rutledge household was a daughter, Ann Mayes, born in Kentucky, January 7, 1813. When Lincoln first met her she was nineteen years old, and as fresh as a flower. Many of those who knew her at that time have left tributes to her beauty and gentleness, and even to-day there are those living who talk of her with moistened eyes and softened tones. "She was a beautiful girl," says her cousin, James McGrady Rutledge, "and as bright as she was pretty. She was well educated for that early day, a good conversationalist, and always gentle and cheerful. A girl whose company people liked." So fair a maid was not, of course, without suitors. The most determined of those who sought her hand was one John McNeill, a young man who had arrived in New Salem from New York soon after the founding of the town. Nothing was known of his antecedents, and no questions were asked. He was understood to be merely one of the thousands who had come West in search of fortune. That he was intelligent, industrious, and frugal, with a good head for business, was at once apparent; for he and Samuel Hill opened a general store and they soon doubled their capital, and their business continued to grow marvellously. In four years from his first appearance in the settlement, besides having a half-interest in the store, he owned a large farm a few miles north of New Salem. His neighbors believed him to be worth about twelve thousand dollars.

[pg 237]John McNeill was an unmarried man—at least so he represented himself to be—and very soon after becoming a resident of New Salem he formed the acquaintance of Ann Rutledge, then a girl of seventeen. It was a case of love at first sight, and the two soon became engaged, in spite of the rivalry of Samuel Hill, McNeill's partner. But Ann was as yet only a young girl; and it was thought very sensible in her and very gracious and considerate in her lover that both acquiesced in the wishes of Ann's parents that, for some time at least, the marriage be postponed.

Such was the situation when Lincoln appeared in New Salem. He naturally soon became acquainted with the girl. She was a pupil in Mentor Graham's school, where he frequently visited, and rumor says that he first met her there. However that may be, it is certain that in the latter part of 1832 he went to board at the Rutledge tavern and there was thrown daily into her company.